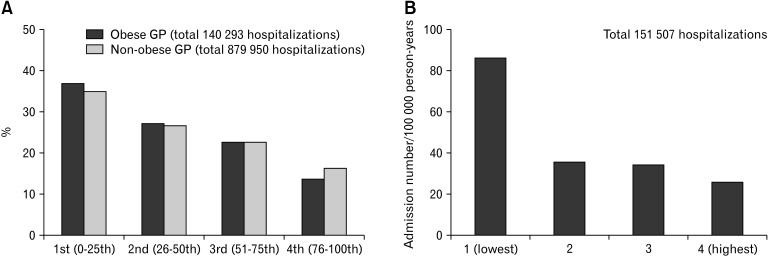

Diverse etiologies involving abnormal gastric motility, gut sensitivity, mucosal inflammation, and various cell changes have been suggested as the pathophysiology of gastroparesis.1 However, gastroparesis lies between functional and organic diseases because its mechanism is not clearly known. In this issue, Dahiya et al2 analyzed the relationship between obesity and gastroparesis hospitalizations in the United States using socioeconomic and racial differences. They found that gastroparesis hospitalizations of obese patients were associated with the female sex and black race. Gastroparesis in obese patients was associated with a longer hospitalization period, high total health costs, and high use of medical resources compared with gastroparesis in non-obese patients. What is noteworthy in their results is that lower income was associated with a higher gastroparesis hospitalization rate regardless of obesity (Figure A). Interestingly, we were able to obtain similar results by re-analyzing the data of a study investigating the incidence of peptic ulcer bleeding between 2006 and 2015 using the Korean National Health Insurance Service Database (Figure B).3

Figure.

The effect of socioeconomic factors is similar across diseases and countries. (A) Distribution of obese and non-obese gastroparesis (GP) hospitalized patients according to household income in the United States. (B) The admission rate for peptic ulcer bleeding according to health insurance holders’ income in Korea.

To unveil the pathophysiology of diseases, including functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) and gastroparesis, various factors that can affect the prevalence and disease course have been analyzed. Depression or anxiety has been commonly evaluated in studies on FGIDs.4 Recently, sex has been recognized as a biological variable and is recommended to be analyzed in all biomedical research.5 However, the effect of socioeconomic factors has not been routinely investigated. There are only a few studies on the impact of socioeconomic factors on gastroparesis. Low household income is related to gastroparesis, and idiopathic gastroparesis is associated with higher income than diabetic gastroparesis.6,7 A recent population study reported that low household income was associated with the highest mortality rate.8

The effect of socioeconomic factors has been studied slightly more in FGIDs than in gastroparesis, so we reviewed it briefly. A large-scale study analyzing 5430 United States households through a survey reported that the lower the household income, the higher the frequency of FGIDs and the severer symptoms.9 Another population-based study reported that low socioeconomic status was a risk factor that increased the prevalence of both upper and lower FGIDs.10 However, there was still a lack of research on the effect of socioeconomic factors on FGIDs. For example, in a meta-analysis of 80 studies to identify the global prevalence and risk factors of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), only 4 studies analyzed the prevalence of IBS according to socioeconomic factors.11 There was no significant difference in the prevalence of IBS according to socioeconomic status, however, it was difficult to draw clear conclusions due to the small number of studies and their heterogeneity.11 Interestingly, 1 of those 4 studies showed that the risk of IBS is higher among high-income men through a sex difference analysis.12 This suggests that more data and detailed analyses are needed because contributing factors such as socioeconomic factors and sex are intertwined. In addition, the impact of socioeconomic factors on IBS prevalence may vary depending on the country or culture.

Despite the importance of socioeconomic factors in clinical studies, there are several obstacles to analyzing them. First, researchers are less interested in the relationship between socioeconomic factors and the disease. Many studies have collected data about the demographic and socioeconomic features, but only marital status and education level were analyzed, or income was only used to correct other data.13 It is even unclear how the socioeconomic class of subjects was classified in some studies.14

Second, it is difficult to obtain reliable data that can accurately reflect the socioeconomic factors of subjects. In face-to-face or questionnaire surveys, there is a tendency not to answer questions about economic status or not to answer them accurately. Therefore, many researchers evaluate socioeconomic factors using indirect data such as the average risk of deprivation in the area of residence, the living house type, or educational level.15,16 However, these variables do not represent the exact personal economic status. In our study, the Korean National Health Insurance Service Database classified the income quintile at the household insurance holder level according to the insurance premiums paid; therefore, the socioeconomic factors for each household could be categorized relatively accurately.3

Then, what is a plausible explanation for the mechanism by which socioeconomic factors affect the pathophysiology of FGIDs? Psychological comorbidities associated with low socioeconomic factors can be considered. It is well known that depression and anxiety are prevalent in patients with FGIDs,4 and low socioeconomic factors are a risk factor related to high anxiety.17 Low socioeconomic factors may have a physiological impact on patients with FGIDs. In particular, the hypothesis that early-life social qualifications impact adult physiology has been raised.18 A study with blood-derived genome-wide transcriptional profiles demonstrated that socioeconomic factors in childhood were associated with continuing upregulation of the inflammatory transcriptome in adulthood.19 These changes persisted independently of socioeconomic experiences in adulthood.18 It can also be presumed that racial differences may be related to socioeconomic factors in a multiracial country. Dahiya et al2 showed a relationship between gastroparesis in obese patients and the black race, suggesting that these 2 factors may be connected by socioeconomic status.

Finding and analyzing additional variables is a difficult and complex process, but this will be an opportunity to find answers and obtain new insights to solve the puzzle of intractable diseases such as FGIDs and gastroparesis. The Rome Foundation surveyed the worldwide prevalence and burden in 2021 and confirmed the relationship between several variables and FGIDs through questionnaires. However, analyzing the effect of socioeconomic factors on the incidence of FGIDs was proposed as a future task.19

In conclusion, future studies on FGIDs should try to find the effects of socioeconomic factors on the prevalence, disease course, and treatment outcome of intractable diseases. Clinicians could get better treatment results than now if new insights based on socioeconomic factors are applied to determine the treatment strategy.20

Footnotes

Financial support: This work is supported by Wonkwang University 2021 (CSC).

Conflicts of interest: None.

Author contributions: Yong Sung Kim, design and writing; and Suck Chei Choi, design and final approval.

References

- 1.Kim BJ, Kuo B. Gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia: a blurring distinction of pathophysiology and treatment. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;25:27–35. doi: 10.5056/jnm18162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahiya DS, Inamdar S, Perisetti A, et al. The conundrum of obesity and gastroparesis hospitalizations: a retrospective comparative analysis of hospitalization characteristics and disparities amongst socioeconomic and racial backgrounds in the United States. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;28:655–663. doi: 10.5056/jnm21232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim YS, Lee J, Shin A, Lee JM, Park JH, Jung HY. A nationwide cohort study shows a sex-dependent change in the trend of peptic ulcer bleeding incidence in Korea between 2006 and 2015. Gut Liver. 2021;15:537–545. doi: 10.5009/gnl20079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee C, Doo E, Choi JM, et al. The increased level of depression and anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome patients compared with healthy controls: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:349–362. doi: 10.5056/jnm16220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee MY, Kim EJ, Shin A, Kim YS. [How to study the sex and gender effect in biomedical research?]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2021;77:104–114. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2021.020. [Korean]fa3f1365e58c4d459221085929189a5a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parkman HP, Yates K, Hasler WL, et al. Similarities and differences between diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:1056–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bielefeldt K, Raza N, Zickmund SL. Different faces of gastroparesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:6052–6060. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.6052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saleem S, Inayat F, Aziz M, Then EO, Zafar Y, Gaduputi V. In-hospital mortality in gastroparesis population and its predictors: a United States-based population study. JGH Open. 2021;5:350–355. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12500.1837c3e351a44bae8d037b63d8619d6f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–1580. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bytzer P, Howell S, Leemon M, Young LJ, Jones MP, Talley NJ. Low socioeconomic class is a risk factor for upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms: a population based study in 15 000 Australian adults. Gut. 2001;49:66–72. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712–721. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husain N, Chaudhry IB, Jafri F, Niaz SK, Tomenson B, Creed F. A population-based study of irritable bowel syndrome in a non-Western population. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:1022–1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noh YW, Jung HK, Kim SE, Jung SA. Overlap of erosive and non-erosive reflux diseases with functional gastrointestinal disorders according to Rome III criteria. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:148–156. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2010.16.2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mearin F, Badía X, Balboa A, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome prevalence varies enormously depending on the employed diagnostic criteria: comparison of Rome II versus previous criteria in a general population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1155–1161. doi: 10.1080/00365520152584770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crooks CJ, West J, Card TR. Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage and deprivation: a nationwide cohort study of health inequality in hospital admissions. Gut. 2012;61:514–520. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gwee KA, Wee S, Wong ML, Png DJ. The prevalence, symptom characteristics, and impact of irritable bowel syndrome in an asian urban community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:924–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nunes JC, Carroll MK, Mahaffey KW, et al. General anxiety disorder-7 questionnaire as a marker of low socioeconomic status and inequity. J Affect Disord. 2022;317:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.08.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castagné R, Kelly-Irving M, Campanella G, et al. Biological marks of early-life socioeconomic experience is detected in the adult inflammatory transcriptome. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38705. doi: 10.1038/srep38705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, et al. Worldwide prevalence and burden of functional gastrointestinal disorders, results of Rome Foundation global study. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:99–114. e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernheim SM, Ross JS, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH. Influence of patients' socioeconomic status on clinical management decisions: a qualitative study. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:53–59. doi: 10.1370/afm.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]