Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of death globally, with acute myocardial infarction being one of the most frequent. One of the complications that can occur after a myocardial infarction is cardiogenic shock. At present, the evidence on the use of inotropic agents for the management of this complication is scarce, and only a few trials have evaluated the efficacy-adverse effects relationship of some agents. Milrinone and Dobutamine are some of the most frequently mentioned drugs that have been studied recently. However, there are still no data that affirm with certainty the supremacy of one over the other. The aim of this review is to synthesize evidence on basic and practical aspects of these agents, allowing us to conclude which might be more useful in current clinical practice, based on the emerging literature.

Keywords: Cardiogenic shock, Myocardial infarction, Cardiovascular diseases, Milrinone, Dobutamine

Highlights

-

•

Studies suggest that Milrinone has a higher safety and efficacy profile over Dobutamine.

-

•

The evidence on the advantages of using Milrinone vs. Dobutamine is heterogeneous.

-

•

Additional factors need to be considered to reduce the risk of adverse events.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death worldwide [1]. They carry most of the global burden of disease, mainly due to the high prevalence of chronic noncommunicable diseases and major cardiovascular events (MACE) (523 million (95% CI, 497 to 550 million cases; and 18.6 million (95% CI, 17.1 to 19.7 million deaths) [2]. Among these, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) stands out as the most frequent and one of the most fatal. Cardiogenic shock (CS) is a severe complication of AMI that causes myocardial dysfunction, systemic failure and death [[3], [4], [5]]. Various therapeutic agents are used to try to compensate for the hemodynamic alteration generated by CS. However, the evidence remains heterogeneous and inconclusive, which may explain why 30-day mortality in CS is greater than 50%. Inotropic drugs allow a change in cardiac contractility to increase cardiac output and improve systemic hemodynamics [[6], [7], [8], [9]]. However, there is still no inotrope that is totally effective, efficient and safe in the management of CS, but some have certain benefits compared to others. Milrinone, a phosphodiesterase III inhibitor with positive inotropic and direct vasodilator activity, had been postulated as the ideal agent after showing superiority over Dobutamine, another commonly used inotropic, in some observational studies [10,11]. However, a recently published clinical trial, which evaluated the use of Milrinone vs. Dobutamine in the management of patients with CS, found no significant differences between these two drugs with respect to primary and secondary outcomes [12]. These results opened a discussion on how to proceed with this group of patients and the limitations of current evidence [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. Considering the importance of CS and decision making on the use of inotropic agents in its management, the aim of this review is to synthesize evidence on the performance of Milrinone and Dobutamine in the management of cardiogenic shock.

2. Methods

A literature search was carried out using search terms such as "Cardiogenic Shock", "Milrinone", "Dobutamine" and "Inotropic Support", as well as synonyms, which were combined with the Boolean operators "AND" and "OR", in the databases PubMed, ScienceDirect, Embase, EBSCO, and MEDLINE. As inclusion criteria, it was determined that any article focused on the pathophysiological description of cardiogenic shock; evaluation, analysis and critique of the use of Milrinone and Dobutamine (in addition to other inotropics), in the context of the patient with cardiogenic shock, would be considered; giving priority to original studies and systematic reviews and meta-analyses. In addition, they had to be available in full text. As non-inclusion criteria, it was established that articles published in a language other than Spanish and English would not be included. Taking into account the breadth of the topic and the wide variety of publications, articles published between 2000 and 2022 were included. A total of 240 potentially relevant articles were identified, with a review of the title and abstract of all of them, of which 47 articles were finally included, after discrimination according to the inclusion and non-inclusion criteria. The estimates and calculations found were expressed in their original measures, whether frequencies, percentages, confidence intervals (CI), mean difference (MD), relative risk (RR), odds ratio (OR) or risk ratio (HR).

3. Physiological and pathophysiological considerations of cardiogenic shock for the choice of inotropic agents

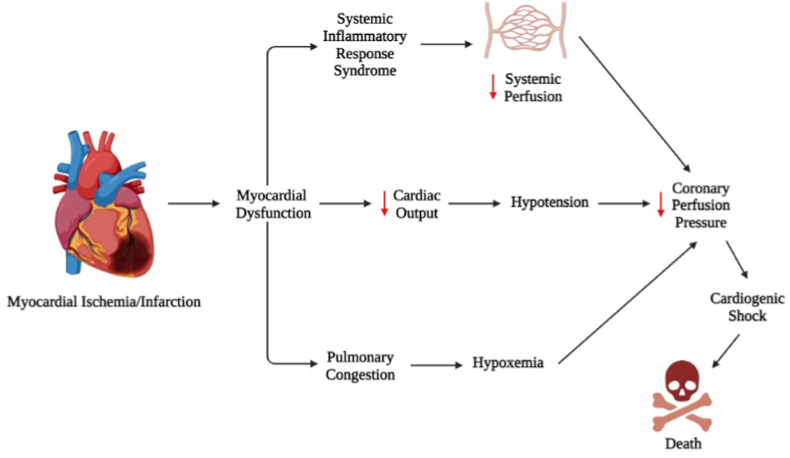

CS is a pathological condition that reflects the absence of effective filling of the blood supply to the heart and consequently to the circulatory system. It is produced by any pathophysiological mechanism that compromises the blood flow of the minor circulation, at the expense of cardiac contractility [17,18]. Although AMI or cardiac ischemia is the most frequent etiology of CS, cardiac tamponade, valvular heart disease, arrhythmias, among other causes, can also lead to this complication. Physiologically, when stroke volumen (SV) decreases, vasopressor agents are triggered that normalize arterial pressure and hemodynamics [19,20]. However, although vasoconstriction may normalize mean arterial pressure, myocardial volume oxygen remains decreased (MVO2), causing altered myocardial contractility, reduced left ventricular ejection volume, decreased cardiac and systemic perfusion, which ultimately leads to CS and death due to multiorgan failure and cardiac arrest [6,[18], [19], [20]] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Description of pathophysiologic mechanisms of cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. Created with BioRender. Source: authors.

Endogenous (Adrenaline, Noradrenaline, Dopamine) and exogenous (Dobutamine, Isoproterenol, Phenylephrine, Milrinone) catecholamines play a key role in the compensatory response and therapeutic management of CS [6]. These are adrenergic receptor agonists, which, through the activation of different signaling pathways, produce vasoconstriction and increased cardiac output. Dobutamine directly stimulates β1 and α1 receptors, with weak affinity for β2 receptors, resulting in direct regulation of mean arterial pressure by increasing cardiac output, at the expense of SV and heart rate [[21], [22], [23]]. At the vascular smooth muscle cell level, stimulation of α1-receptors in an agonist and antagonist manner by Dobutamine triggers mild vasodilatation (especially at low doses, such as <5 mcg/kg/min). Even at doses <15 mcg/kg/min, there is a potentiation of inotropism without affecting peripheral vascular resistance. But at higher doses, it causes strong vasoconstriction [6,[20], [21], [22], [23]] (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics of the included observational studies on Milrinone or Dobutamine in the management of cardiogenic shock [[29], [30], [31], [32], [33]].

| Authors | Objective | Methods | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lewis et al. [29] | To compare the efficacy and safety of Dobutamine vs. Milrinone in the initial management of cardiogenic shock | Single-center retrospective study, including 622 patients (217 received Milrinone and 405 received Dobutamine) | Shock resolution was similar in both groups (Milrinone 76% vs Dobutamine 70%, p = 0.50). The median time to resolution in both groups was 24 h. There were no significant differences in hemodynamic changes in the use of the two inotropics. However, arrhythmia occurred more frequently in the Dobutamine group vs. the comparison group (62.9% vs. 32.8%, p < 0.01) | Milrinone and Dobutamine exhibited a similar efficacy and safety profile, but with differences with respect to adverse events. Therefore, the choice depends on the tolerance of adverse events |

| Tarvasmäki et al. [30] | To evaluate the impact of inotropic and vasopressor use on outcomes and changes in cardiac and renal parameters in patients with cardiogenic shock | Prospective multinational study that included 216 patients | The use of Dobutamine as an inotropic, combined with Adrenaline as a vasopressor, increases mortality at 90 days (48% vs 35%, p < 0.06). Levosimendan performed better as an inotrope when combined with a vasopressor (<0.001) | The use of Dobutamine as an inotropic, in combination with adrenaline as a vasopressor, increases 90-day mortality and is associated with worsening of cardiac and renal markers |

| Rohm et al. [31] | To evaluate the use of inotropics and vasopressors as predictors of mortality in cardiogenic shock | Single-center retrospective study, which included 276 patients | Using Dobutamine vs. Milrinone did not significantly modify mortality (HR 1.31; 95% CI, 0.88–1.96, p = 0.18 vs. HR 1.18; 95% CI 0.82–1.71, p = 0.37). However, when combined with one or more vasopressors, this behavior varies | There is no difference between using Dobutamine or Milrinone independently for the management of cardiogenic shock. However, mortality varies according to the combination with certain vasopressors |

| Nandkeolyar et al. [32] | To evaluate mortality and risk of in-hospital mortality in the use of inotropes in the management of cardiogenic shock. | Retrospective study including 342 patients | Each 1 μg/kg/min increase in Dobutamine raise mortality by 15%. A dose >3 μg/kg/min is associated with a three times increased risk of death. Milrinone was not found to be associated with mortality. | Unlike other inotropics such as Milrinone, Norepinephrine and Dopamine, Dobutamine is independently associated with mortality |

| Gao et al. [33] | To determine which inotropic is associated with any cause of mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock | Multicenter retrospective cohort study, which included 15,021 patients | In-hospital mortality was higher in those patients in whom inotropics were used (HR 2.24; 95% CI: 2.09–2.39, p < 0.0001). The administration of Milrinone was associated with lower mortality (OR 0.559; 95% CI: 0.430–0.727, p < 0.001), compared to the use of Dobutamine, which increased the risk of mortality. | Low doses of Norepinephrine and Milrinone are associated with lower mortality, while Dobutamine increased the risk of death |

By increasing cardiac output, Dobutamine counteracts the pathophysiological mechanisms of hypoxia in CS, improving cerebral oxygenation in case of decreased cerebral perfusion pressure due to lack of β1 receptor stimulation; therefore, it is very useful in patients with impaired neurological status or in patients with ischemic stroke and simultaneous cardiac involvement [6,24]. However, it should be noted that if during shock there is a decrease in cardiac output but maintenance of peripheral vascular resistance, Dobutamine can regulate blood pressure and hemodynamics without problem. However, if the decrease in peripheral vascular resistance is severe and the increase in cardiac output is not proportional, a state of persistent hypotension with vasodilatory shock may occur [[25], [26], [27]]. Considering the half-life of Dobutamine (<2 min), this agent achieves a rapid compensation of cardiac output in patients with post-infarction shock, which is favorable even in cases requiring rapid stabilization for transfer to specialized management. In this order of ideas, the benefit of Dobutamine will depend on the dose-response relationship, where a high dose infusion can provoke tachycardia without a proportional increase in SV [6], which would be negative in the presence of arrhythmias; therefore, it should be used with caution.

Table 2.

Summary of the characteristics of the included clinical trials on Milrinone or Dobutamine in the management of cardiogenic shock [12,[34], [35], [36]].

| Authors | Objective | Methods | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mathew et al. [12] | To evaluate the efficacy of Milrinone vs. Dobutamine in patients with cardiogenic shock | Randomized double-blind clinical trial involving 192 participants (96 in each group) | No significant differences were found with respect to in-hospital mortality (RR 0.85; 95% CI, 0.60–1.21), cardiac resuscitation (RR 0.78; 95% CI, 0.29–2.07), receipt of mechanical circulatory support (RR 0.78; 95% CI, 0.36–1.71) and initiation of renal replacement therapy (RR 1.39; 95% CI, 0.73–2.67), in both groups. | In patients with cardiogenic shock, there are no significant differences between the use of Milrinone vs. Dobutamine, with respect to primary outcomes (mortality and need for specialized approach) and secondary outcomes |

| Parlow et al. [34] | To evaluate the impact of mean arterial pressure in patients with cardiogenic shock under treatment with Milrinone or Dobutamine | Post hoc analysis of the CAPITAL DOREMI clinical trial. Where two intervention arms were established (mean arterial pressure ≥70 mmHg per 36 h vs. mean arterial pressure ≤70 mmHg per 36 h) | Primary outcomes (all-cause mortality, resuscitated cardiac arrest, need for cardiac transplantation, stroke or initiation of renal therapy) were more frequent in the group with low mean arterial pressure (67.6% vs. 42.2%). | In patients with cardiogenic shock under treatment with Milrinone or Dobutamine, low mean arterial pressure values are associated with worse outcomes |

| Di Santo et al. [35] | To evaluate clinical and hemodynamic outcomes in the use of beta-blockers in patients with cardiogenic shock under treatment with Dobutamine or Milrinone | Subgroup analysis of the DOREMI clinical trial. 192 patients were included, and primary outcomes (all-cause mortality, resuscitated cardiac arrest, need for cardiac transplantation, stroke or initiation of renal therapy, among others) were evaluated | 93 patients received beta-blockers. Primary outcomes occurred in 51% of the intervention group vs. 53% in the control group (RR 0.96; 95% CI 0.73–1.27; p = 0.78). Lower mortality was observed in the intervention group (RR 0.41; 95% CI 0.18–0.95; p = 0.03) | The use of beta-blockers 24 h prior to the development of cardiogenic shock with Dobutamine or Milrinone management, did not influence clinical and hemodynamic outcomes. However, their use showed a slight reduction in mortality |

| Jung et al. [36] | To evaluate the implications of acute myocardial infarction in patients with cardiogenic shock under treatment with Milrinone and Dobutamine | Subgroup analysis of the DOREMI clinical trial. 192 patients were included (65 with acute myocardial infarction vs. 127 without infarction). | Higher all-cause mortality, need for mechanical circulatory support and initiation of renal therapy were observed in the infarction group (HR 2.21; 95% CI, 1.47–3.30; p = 0.0001). Inotropic was found to be associated, although not significantly, with final outcome. | Acute myocardial infarction is significantly associated with worse clinical outcomes, mainly with initiation of mechanical circulatory support and mortality |

Table 3.

Summary of the characteristics of the included systematic reviews and meta-analyses on Milrinone or Dobutamine in the management of cardiogenic shock [[39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44]].

| Authors | Objective | Methods | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unverzagt et al. [39] | To evaluate the safety, efficacy and efficiency of the use of inotropics and vasodilators in cardiogenic shock secondary to acute myocardial infarction | Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, including a total of 63 patients | Among the agents evaluated, Levosimendan was shown to slightly increase survival, compared to Enoximone, which also stood out for its performance (HR 0.33; 95% CI 0.11–0.97). The evidence was imprecise regarding the differences in the use of Dobutamine vs Levosimendan | No robust evidence to distinguish the benefits between inotropics and vasodilators, with the aim of improving mortality |

| Schumann et al. [40] | To evaluate the safety, efficacy and efficiency of the use of inotropics and vasodilators in cardiogenic shock secondary to acute myocardial infarction | Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, including a total of 2001 patients | Serious statistical and interest limitations were evident in these studies. It was found that Levosimendan can reduce short-term mortality compared to Dobutamine (RR 0.60; 95% CI, 0.37–0.95). Inaccurate effects were observed when comparing other groups, including Milrinone | The available evidence is scarce and of low quality. However, it suggests that the use of Levosimendan decreases short-term mortality, compared to Dobutamine |

| Uhlig et al. [41] | To evaluate the safety, efficacy and efficiency of the use of inotropics and vasodilators in cardiogenic shock secondary to acute myocardial infarction | Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, including a total of 2385 patients | Serious limitations due to risk of bias were evidenced. Nevertheless, it was observed that Levosimendan decreases short and long term mortality, compared to Dobutamine, but the latter improves survival compared to Epinephrine/Norepinephrine | There is insufficient evidence to determine that there is a specific inotropic or vasodilator that reduces mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock |

| Liao et al. [42] | To synthesize evidence on the most favorable choice of drugs for the management of cardiogenic shock | Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, including a total of 1806 patients. | Among the agents evaluated (Dopamine, Dobutamine, Epinephrine, Norepinephrine, Milrinone and Levosimendan), Milrinone has the highest reduction in mortality and a low incidence of adverse events | Milrinone is the most effective therapeutic agent for reducing mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock, with a good risk-benefit balance with respect to adverse events |

| Karami et al. [43] | To evaluate the routine effect of inotropic and vasopressor drugs on mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock secondary to acute myocardial infarction | Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials and observational studies, including 2478 patients | No differences were found between the use of Adrenaline, Noradrenaline, Vasopressin, Milrinone, Levosimendan, Dobutamine or Dopamine, on mortality. However, Levosimendan was associated with better outcomes (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.47–1.00), although these results were not significant | There is insufficient evidence to determine differences between vasopressors and inotropics on mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock |

| Mathew et al. [44] | To compare the effectiveness and safety of Dobutamine vs. Milrinone in cardiogenic shock | Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials and observational studies, including 23,056 patients. | Although Milrinone is associated with greater survival (OR 1.13; 95% CI 1.00–1.29, p = 0.06), this result is not significant. On the other hand, the use of Dobutamine is associated with a shorter stay in intensive care and hospitalization | There is insufficient evidence to determine with certainty which agent is safer and more effective. However, it appears that the use of Dobutamine decreases intensive care stay, but increases all-cause mortality |

Milrinone is a phosphodiesterase 3 inhibitor, simulating the stimulation of β1 and β2 receptors [28]. The properties that make this agent stand out from other inotropic agents are its ability to increase inotropism while generating a significant reduction in peripheral vascular resistance and pulmonary vascular resistance [[20], [21], [22]]. Unlike Dobutamine, Milrinone has a prolonged half-life, which makes it particularly effective in compensating patients with chronic heart failure with lack of β-adrenergic receptor stimulation [6]. Considering that Milrinone does not directly stimulate β1 receptors, its inotropic activity is maintained in the presence of beta-blockers [18,19]. Even the combination of Milrinone with a β1-agonist can more effectively regulate cardiac output, but could lead to severe adverse effects. Although it is the drug of choice in patients with low cardiac output and high peripheral vascular resistance, it should be used with caution because of the risk of hypotension and worsening of shock [6,[23], [24], [25]]. So far, it can be observed that both Dobutamine and Milrinone are potent therapeutic agents, but they should be used under certain considerations and taking into account some physiological and pathophysiological factors. Then, their use will depend on the patient's context and the risk-benefit balance.

4. Available evidence on Milrinone vs. Dobutamine as inotropic support in cardiogenic shock

4.1. Observational studies

Among the observational studies that met the inclusion criteria [[29], [30], [31], [32], [33]], two cross-sectional studies [29,31] and three cohort studies were found [30,32,33]. Lewis et al. [29], conducted a retrospective review of 100 adult patients (50 in each group) with CS, with the aim of evaluating the impact of Milrinone vs Dobutamine with respect to shock resolution. They showed that the incidence of shock resolution was similar in both groups (76% vs 70%, p = 0.50), the median time to resolution in both groups was 24 h and there were no significant differences in hemodynamic changes. However, the presence of arrhythmias was more frequent in the Dobutamine group (62.9% vs 32.8%, p < 0.01), but similar frequencies with respect to the occurrence of hypotension (49.2% vs 40.3%, p = 0.32) [29]. This led to the conclusion that both agents share a similar efficacy and safety profile.

Rohm et al. [31] conducted a cross-sectional study in which they studied 276 patients with CS, different inotropic and vasopressor drugs, in addition to Impella devices. When subgroup analysis was performed, it was found that there was no significant difference between the use of Dobutamine vs. Milrinone on mortality (44.4% vs. 35.7%, p = 0.41). However, it was shown that the use of multiple inotropic drugs did increase mortality. Tarvasmäki et al. [30] performed a subgroup analysis of the prospective multicenter CardShock study, where they evaluated the use of certain inotropes and vasopressors on mortality in 216 patients with CS. The authors found adrenaline use to be an independent predictor of 30-day mortality (OR 5.2; 95% CI, 1.88–14.7, p = 0.002). Dobutamine and Levosimendan were the most commonly used inotropics with adrenaline, exhibiting a similar efficacy and safety profile [30]. Therefore, it was found that there are no significant differences between Dobutamine and other inotropes.

However, Nandkeolyar et al. [31] conducted a cohort study in which they evaluated the independent or combined use of inotropic drugs in 342 patients with CS, observing that each 1 μg/kg/minute increase in Dobutamine increases the risk of death by up to 15%. Doses >3 μg/kg/minute increase the risk of death up to threefold [31]. This study, unlike the others, found that Dobutamine was the only inotrope significantly associated with mortality. Gao et al. [32] performed a retrospective cohort study with 34,381 patients with cardiogenic shock, where 15,021 received inotropics. Mortality was higher in the group where inotropics were used (2999 [24.03%] vs. 1547 [12.40%]; HR 2.24; 95% CI, 2.09–2.39; p < 0.0001). The use of Milrinone was associated with lower mortality (OR 0.559; 95% CI, 0.430–0.727, p < 0.001), while the administration of Dobutamine, Epinephrine, Norepinephrine and Dopamine, was associated with higher mortality [32]. In this order of ideas, observational studies differ on the superiority of Dobutamine vs. Milrinone; although it is observed that Dobutamine is associated with greater presence of adverse effects and mortality. Regarding the number of medications, it must be taken into account that sicker patients may need a greater number of medications, and this could explain the elevated mortality risk in observational studies; therefore, it cannot be stated with certainty that the number of medications is independently associated with mortality in this group of individuals.

4.2. Clinical trials

During the literature review, 4 randomized clinical trials were found that met the inclusion criteria [12,[34], [35], [36]], highlighting the most recent published one [12].

Mathew et al. [12] conducted a randomized double-blind clinical trial (DOREMI trial), which included 192 patients with cardiogenic shock divided into two groups (96 in each group), who were administered Milrinone or Dobutamine. The primary outcomes assessed were in-hospital death from any cause, resuscitated cardiac arrest, mechanical circulatory support or need for cardiac transplantation, nonfatal acute myocardial infarction, initiation of renal replacement therapy, or stroke. Primary outcomes occurred more frequently in the Dobutamine group compared to Milrinone (54% vs 49%; RR 0.90; 95% CI, 0.69–1.19, p = 0.47). However, these were not significant. When analyzing the difference by event, there were also no significant differences on in-hospital mortality (37% vs. 43%, RR 0.85; 95% CI, 0.60–1.21), resuscitated cardiac arrest (7% vs. 9%, HR 0.78; 95% CI, 0.29–2.07), need for mechanical circulatory support (12% vs. 15%, HR 0.78; 95% CI, 0.36–1.71), or initiation of renal replacement therapy (22% vs. 17%, HR 1.39; 95% CI, 0.73–2.67) [12]. In this order of ideas, this last trial, which was one of the most robust, could not demonstrate the superiority of Milrinone over Dobutamine with respect to morbidity and mortality.

Other recent trials, such as that of Parlow et al. [34] who associated mean arterial pressure values with outcomes in patients with cardiogenic shock and treated with inotropics in a post-hoc analysis of the DOREMI trial, also found no differences with respect to the groups treated with different inotropics, but only punctually on mean arterial pressure control (lower morbidity and mortality in those with >70 mmHg, RR 0.70; 95% CI, 0.53–0.92, p = 0.01) [34]. Di santo et al. [35], who performed an analysis similar to that of Parlow et al. [34], but this time evaluating the impact of beta-blocker use on inotropic response in this group of patients, found that primary outcomes were more frequent in the control group (51% vs 53%, RR 0.96; 95% CI, 0.73–1.27, p = 0.78). Higher survival was found in the intervention group (RR 0.41; 95% CI 0.18–0.95, p = 0.03), with no differences in any other analysis [35]. Therefore, there was also no significant difference between the combination of beta-blockers and Dobutamine or Milrinone.

For their part, Jung et al. [36] decided to evaluate the difference between the outcomes of the AMI and non-AMI groups through a subgroup analysis of the DOREMI trial. Although in this case the difference in group size was significant (AMI: 65 vs non-AMI:127), the authors found that primary outcomes were more frequent in the AMI group (HR 2.21; 95% CI, 1.47–3.30; p = 0.0001). As in the rest of the post-hoc analyses, no differences were found between the outcome evaluated and the use of a specific inotropic. In this order of ideas, the current experimental evidence of better quality does not demonstrate superiority between Milrinone and Dobutamine.

Recently, a post-hoc analysis of the DOREMI trial was performed on the impact of lactate clearance as a predictor of mortality in cardiogenic shock [37], showing that although there is no difference in lactate clearance in both intervention groups, complete clearance is an independent predictor strongly associated with survival at 8 h (OR 2.46; 95% CI 1.09–5.55, p = 0.03) and 24 h (OR 5.44; 95% CI, 2.14–13.8, p < 0.01) [37]. This raises an interesting field for a possible therapeutic target in future studies. Currently, the phase 4 CAPITAL DOREMI-2 trial is in progress to recruit 346 individuals to compare outcomes in cardiogenic shock with the use of Milrinone or Dobutamine vs. placebo to assess whether these two inotropic agents are potentially necessary. This study is expected to be completed by 2026 [38]. This study could provide an answer to the current knowledge gap on this topic.

4.3. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

During the literature review, 6 systematic reviews and meta-analyses were found that met the inclusion criteria [[39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44]].

Currently, the Cochrane Collaboration has published 3 systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the impact of inotropic drugs on mortality in CS, the most updated being the one from 2020 [41]. The first, published in 2014 [39], included a small sample of 63 patients (3 studies) with a high risk of bias, from randomized clinical trials comparing Levosimendan vs. other agents. There was no evidence to compare Dobutamine vs. Levosimendan or Milrinone [39], therefore, it was concluded that by that date there was insufficient evidence to define which inotropic agent was more effective and safe in the management of CS. By 2018, the second updated review was published, where there were only less than 10 studies with less than 2000 patients [40]. There was evidence that Levosimendan reduced mortality compared to Dobutamine (RR 0.60; 95% CI, 0.37–0.95), but there were no data on Milrinone. At that time, there was no conclusive evidence and the risk of bias in the studies was still very high (>50%) [40]. The latest updated review was published in 2020 and included 19 studies with 2385 individuals [41]. Levosimendan continues to prove superior to Dobutamine (RR 0.60; 95% CI, 0.36–1.03) in reducing short-term mortality. This same behavior was observed in other inotropics when compared with Dobutamine, but there was also no evidence to compare Dobutamine with Milrinone [41], so at present the synthesized evidence has many limitations.

Mathew et al. [44] performed a systematic review and meta-analysis including 11 studies, of which only one was a clinical trial, obtaining a total of 23,056 individuals. With respect to survival, Milrinone exhibits a superior profile to Dobutamine, but this estimate is not statistically significant (OR 1.13; 95% CI, 1.00–1.29, p = 0.06) [44]. Similarly, Milrinone reduces intensive care stay (MD -0.72; 95% CI, −1.10 to −0.34, p = 0.0002), but not hospitalization, compared to Dobutamine; and unlike observational studies, there were no significant differences with respect to the incidence of adverse events in both groups (OR 1.78; 95% CI, 0.85–3.76, p = 0.13) [44]. Liao et al. [42], also performed the same study design, where they included 28 studies with 1806 patients, corroborating that the risk of bias of primary studies that have evaluated Milrinone vs. Dobutamine is very high, and that there are no significant differences between the different inotropics. However, they found that Milrinone had the lowest incidence of adverse events, but was not superior to another inotropic [42]. Finally, Karami et al. [43] in their systematic review and meta-analysis including 19 studies with 2478 patients with cardiogenic shock, showed that there is no significant difference between the different inotropic drugs on mortality. However, Levosimendan tends to show better outcomes compared to control groups (RR 0.69; 95% CI, 0.47–1.00), although this association is not significant either [43]. The authors conclude that the evidence remains heterogeneous and very limited due to the risk of bias and statistical imprecision. In this order of ideas, the currently synthesized evidence cannot define superiority between Milrinone vs. Dobutamine, or other inotropics.

Considering the limitations of the evidence and the different clinical and systemic scenarios in the management of the patient with cardiogenic shock, caution should be exercised when claiming that one inotrope is superior to another. Many studies report a significant risk of bias and their groups are heterogeneous. Much of the evidence available from observational studies and clinical trials derives from subgroup analyses and not from specific interventions between these two drugs. Not to mention, evidence-based medicine now takes into account factors such as ethnicity and eco-epidemiology to more closely assess the accuracy of the effect of an intervention [[45], [46], [47]]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to design and execute prospective studies with a high level of evidence to provide results from low- and middle-income countries in order to analyze the behavior of this particular population.

5. Conclusions

The evidence on the advantages of using Milrinone over Dobutamine is heterogeneous and inconclusive. However, some studies suggest that Milrinone has a higher safety and efficacy profile over Dobutamine; but additional factors need to be considered to reduce the risk of adverse events. Robust studies of the highest quality are needed to define precisely which drug is most favorable in the management of cardiogenic shock.

Ethical approval

It is not necessary.

Sources of funding

None.

Author contribution

All authors equally contributed to the analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Research registration Unique Identifying number (UIN)

-

1.

Name of the registry: Not applicable.

-

2.

Unique Identifying number or registration ID: Not applicable.

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): Not applicable.

Guarantor

Alexis Narvaez-Rojas. Department of Surgery, Hospital Carlos Roberto Huembes, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Nicaragua, Managua, Nicaragua. Email: axnarvaez@gmail.com.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Contributor Information

Ivan David Lozada Martinez, Email: ilozadam@unicartagena.edu.co.

Andrea Juliana Bayona-Gamboa, Email: andreabayonag96@gmail.com.

Duvier Fabián Meza-Fandiño, Email: duvfabian@gmail.com.

Omar Andrés Paz-Echeverry, Email: omarandres777@gmail.com.

Ángela María Ávila-Bonilla, Email: Amab155@hotmail.com.

Mario Javier Paz-Echeverry, Email: mariopaz1888@gmail.com.

Frank Jaider Pineda-Trujillo, Email: Fjpt.brs@gmail.com.

Gina Paola Rodríguez-García, Email: ginrodriguez@uan.edu.co.

Jaime Enrique Covaleda-Vargas, Email: je.covaleda11@uniandes.edu.co.

Alexis Rafael Narvaez-Rojas, Email: axnarvaez@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Bhimaraj A. The scourge of cardiogenic shock. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2020;16(1):5–6. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-16-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth G.A., Mensah G.A., Johnson C.O., Addolorato G., Ammirati E., Baddour L.M., et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020;76(25):2982–3021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samsky M.D., Morrow D.A., Proudfoot A.G., Hochman J.S., Thiele H., Rao S.V. Cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction: a review. JAMA. 2021;326(18):1840–1850. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.18323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Atta A., Zaidan M., Abdalwahab A., Asswad A.G., Egred M., Zaman A., et al. Mechanical circulatory support in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022;23(2):71. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm2302071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg D.D., Bohula E.A., Morrow D.A. Epidemiology and causes of cardiogenic shock. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care. 2021;27(4):401–408. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kislitsina O.N., Rich J.D., Wilcox J.E., Pham D.T., Churyla A., Vorovich E.B., et al. Shock - classification and pathophysiological principles of therapeutics. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2019;15(2):102–113. doi: 10.2174/1573403X15666181212125024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell J.A. Vasopressor therapy in critically ill patients with shock. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(11):1503–1517. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05801-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaddoura R., Elmoheen A., Badawy E., Eltawagny M.F., Seif M.A., Bashir K., et al. Vasoactive pharmacologic therapy in cardiogenic shock: a critical review. J Drug Assess. 2021;10(1):68–85. doi: 10.1080/21556660.2021.1930548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furer A., Wessler J., Burkhoff D. Hemodynamics of cardiogenic shock. Interv Cardiol Clin. 2017;6(3):359–371. doi: 10.1016/j.iccl.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallabhajosyula S. Trials, tribunals, and opportunities in cardiogenic shock research. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022;15(3):305–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Megaly M., Buda K., Alaswad K., Brilakis E.S., Dupont A., Naidu S., et al. Comparative analysis of patient characteristics in cardiogenic shock studies: differences between trials and registries. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022;15(3):297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathew R., Di Santo P., Jung R.G., Marbach J.A., Hutson J., Simard T., et al. Milrinone as compared with dobutamine in the treatment of cardiogenic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;385(6):516–525. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2026845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva-Rued M.L., Ramírez-Romero A., Guerra-Maestre L.R., Forero-Hollmann Á.M., Lozada-Martínez I.D. The need to develop specialized surgical centers: the evidence that surgical diseases cannot wait. Int. J. Surg. 2021;92 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aguas-Salazar O.C., Villaveces-Buelvas M.A., Martínez-Ocampo J.C., Lozada-Martinez I.D. Systemic hemodynamic atherothrombotic syndrome: the real agent to consider for 24-h management of hypertension and cardiovascular events. Indian J. Med. Specialities. 2021;12:235–236. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Llamas Nieves A.E., Lozada Martínez I.D., Torres Llinás D.M., Manzur Jattin F., Cardales Periñán M. Novedades sobre angiotensina II y fibrilación auricular: de lo molecular a lo fisiopatológico. Rev. Ciencias Biomed. 2021;10(2) 109-1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lozada-Martinez I.D., Bolaño-Romero M.P. Youth and cardiovascular health: what risk factors should we take into account to intervene? Ciencia e Innovación en Salud. 2021;e117 071-087. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vahdatpour C., Collins D., Goldberg S. Cardiogenic shock. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019;8(8) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.011991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Diepen S., Katz J.N., Albert N.M., Henry T.D., Jacobs A.K., Kapur N.K., et al. Contemporary management of cardiogenic shock: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2017;136(16):e232–e268. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tewelde S.Z., Liu S.S., Winters M.E. Cardiogenic shock. Cardiol. Clin. 2018;36(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapur N.K., Thayer K.L., Zweck E. Cardiogenic shock in the setting of acute myocardial infarction. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2020;16(1):16–21. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-16-1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brener M.I., Rosenblum H.R., Burkhoff D. Pathophysiology and advanced hemodynamic assessment of cardiogenic shock. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2020;16(1):7–15. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-16-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim H.S. Cardiogenic shock: failure of oxygen delivery and oxygen utilization. Clin. Cardiol. 2016;39(8):477–483. doi: 10.1002/clc.22564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAtee M.E. Cardiogenic shock. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. 2011;23(4):607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Brien C., Beaubien-Souligny W., Amsallem M., Denault A., Haddad F. Cardiogenic shock: reflections at the crossroad between perfusion, tissue hypoxia, and mitochondrial function. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020;36(2):184–196. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chioncel O., Adamo M., Bauersachs J. Risk Stratification in Cardiogenic Shock: from clinical utility to improving outcomes. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022;24(4) doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2465. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delmas C., Porterie J., Jourdan G., Lezoualc'h F., Arnaud R., Brun S., et al. Effectiveness and safety of a prolonged hemodynamic support by the IVAC2L system in healthy and cardiogenic shock pigs. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.809143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arai R., Fukamachi D., Migita S., Miyagawa M., Ohgaku A., Koyama Y., et al. Prognostic significance of a combination of cardiogenic shock and the critical culprit lesion location in ST-elevation myocardial infarctions. Int. Heart J. 2022 doi: 10.1536/ihj.21-296. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shankar A., Gurumurthy G., Sridharan L., Gupta D., Nicholson W.J., Jaber W.A., et al. A clinical update on vasoactive medication in the management of cardiogenic shock. Clin. Med. Insights Cardiol. 2022;16 doi: 10.1177/11795468221075064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis T.C., Aberle C., Altshuler D., Piper G.L., Papadopoulos J. Comparative effectiveness and safety between milrinone or dobutamine as initial inotrope therapy in cardiogenic shock. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 2019;24(2):130–138. doi: 10.1177/1074248418797357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarvasmäki T., Lassus J., Varpula M., Sionis A., Sund R., Køber L., et al. Current real-life use of vasopressors and inotropes in cardiogenic shock - adrenaline use is associated with excess organ injury and mortality. Crit. Care. 2016;20(1):208. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1387-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rohm C.L., Gadidov B., Ray H.E., Mannino S.F., Prasad R. Vasopressors and inotropes as predictors of mortality in acute severe cardiogenic shock treated with the Impella device. Cardiovasc. Revascularization Med. 2021;31:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nandkeolyar S., Doctorian T., Fraser G., Ryu R., Fearon C., Tryon D., et al. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in cardiogenic shock patients on vasoactive or inotropic support. Clin. Med. Insights Cardiol. 2021;15 doi: 10.1177/11795468211049449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao F., Zhang Y. Inotrope use and intensive care unit mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock: an analysis of a large electronic intensive care unit database. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.696138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parlow S., Di Santo P., Mathew R., Jung R.G., Simard T., Gillmore T., et al. The association between mean arterial pressure and outcomes in patients with cardiogenic shock: insights from the DOREMI trial. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care. 2021;10(7):712–720. doi: 10.1093/ehjacc/zuab052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Santo P., Mathew R., Jung R.G., Simard T., Skanes S., Mao B., et al. Impact of baseline beta-blocker use on inotrope response and clinical outcomes in cardiogenic shock: a subgroup analysis of the DOREMI trial. Crit. Care. 2021;25(1):289. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03706-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung R.G., Di Santo P., Mathew R., Abdel-Razek O., Parlow S., Simard T., et al. Implications of myocardial infarction on management and outcome in cardiogenic shock. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021;10(21) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.021570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marbach J.A., Di Santo P., Kapur N.K., Thayer K.L., Simard T., Jung R.G., et al. Lactate clearance as a surrogate for mortality in cardiogenic shock: insights from the DOREMI trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022;11(6) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.023322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clinical Trials Capital DOREMI 2: inotrope versus placebo therapy for cardiogenic shock (DOREMI-2) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05267886 [Internet]. [Consulted 20 Apr 2022]. Available in:

- 39.Unverzagt S., Wachsmuth L., Hirsch K., Thiele H., Buerke M., Haerting J., et al. Inotropic agents and vasodilator strategies for acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock or low cardiac output syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009669.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schumann J., Henrich E.C., Strobl H., Prondzinsky R., Weiche S., Thiele H., et al. Inotropic agents and vasodilator strategies for the treatment of cardiogenic shock or low cardiac output syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018;1(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009669.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uhlig K., Efremov L., Tongers J., Frantz S., Mikolajczyk R., Sedding D., et al. Inotropic agents and vasodilator strategies for the treatment of cardiogenic shock or low cardiac output syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020;11(11) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009669.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liao X., Qian L., Zhang S., Chen X., Lei J. Network meta-analysis of the safety of drug therapy for cardiogenic shock. J Healthc Eng. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/8862256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karami M., Hemradj V.V., Ouweneel D.M., den Uil C.A., Limpens J., Otterspoor L.C., et al. Vasopressors and inotropes in acute myocardial infarction related cardiogenic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9(7):2051. doi: 10.3390/jcm9072051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mathew R., Visintini S.M., Ramirez F.D., DiSanto P., Simard T., Labinaz M., et al. Efficacy of milrinone and dobutamine in low cardiac output states: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Invest. Med. 2019;42(2):E26–E32. doi: 10.25011/cim.v42i2.32813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mass-Hernández L.M., Acevedo-Aguilar L.M., Lozada-Martínez I.D., Osorio-Agudelo L.S., Maya-Betancourth J.G.E.M., Paz-Echeverry O.A., et al. Undergraduate research in medicine: a summary of the evidence on problems, solutions and outcomes. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond). 2022;74 doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lozada-Martínez I.D., Acevedo-Aguilar L.M., Mass-Hernández L.M., Matta-Rodríguez D., Jiménez-Filigrana J.A., Garzón-Gutiérrez K.E., et al. Practical guide for the use of medical evidence in scientific publication: recommendations for the medical student: narrative review. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond). 2021;71 doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pérez-Fontalvo N.M., De Arco-Aragón M.A., Jimenez-García J.D.C., Lozada-Martinez I.D. Molecular and computational research in low- and middle-income countries: development is close at hand. J. Taibah. Univ. Med. Sci. 2021;16(6):948–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2021.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]