Abstract

Familial emotional word usage has long been implicated in symptom progression in schizophrenia. However, few studies have examined caregiver emotional word usage prior to the onset of psychosis, among those with a clinical high-risk (CHR) syndrome. The current study examined emotional word usage in a sample of caregivers of CHR individuals (N = 37) and caregivers of healthy controls (N = 40) and links with clinical symptoms in CHR individuals. Caregivers completed a speech sample task in which they were asked to speak about the participant; speech samples were then transcribed and analyzed for general positive (e.g. good) and negative (e.g., worthless) emotional words as well as words expressing three specific negative emotions (i.e., anxiety, anger, and sadness) using Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC). Findings indicated that (1) CHR caregivers used more negative and anxiety words compared to control caregivers; and (2) less positive word usage among CHR caregivers were related to more positive symptomatology among CHR individuals. These findings point toward the utility of automated language analysis in assessing the intersections between caregiver emotional language use and psychopathology.

Keywords: Clinical high-risk, Schizophrenia, Family environment, Language, LIWC

1. Introduction

Family environment has long been thought to play a fundamental role in psychopathology (Hooley, 1985). In particular, there is a tradition examining the role of family environment, such as expressed emotion (EE), in the development and maintenance of symptoms in psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia (Bachmann et al., 2002; Barrowclough and Hooley, 2003; Brown et al., 1962; Kuipers and Bebbington, 1988; Vaughn and Leff, 1976). However, work investigating caregiver language use among individuals at clinical high-risk (CHR) for psychosis is more limited. Importantly, automated language analysis tools may be one way to assess caregiver emotional word usage and has several benefits (e.g., efficient, limited biases, does not require extensive training). As such, the present study is the first, to our knowledge, to apply language analysis using Linguistic Inquiry Word Count (LIWC; Pennebaker et al., 2015) to assess emotional word usage in caregivers of those with a CHR syndrome and to examine links with symptoms.

Emotions can manifest in different ways, including in spoken language (Lindquist et al., 2016; Pennebaker et al., 2003). The words that we use can provide a great deal of information regarding emotional states, which in turn, can be alternatively useful or detrimental in social interactions. It is possible to get a general sense if someone is experiencing joy or anger from the language used in conversation (Fussell, 2002). Research at the intersection between affective and clinical science have shown that the mere frequency of emotional word usage in spoken language predicts important mental and physical health outcomes (Fung et al., 2017; Minor et al., 2015). Much of the foundation of research on language use and physical or mental health has involved written narratives about personal experiences (Pennebaker et al., 2003; Tausczik and Pennebaker, 2010). The efficacy of psychotherapeutic approaches (e.g., talking about emotional experiences) has led to an interest in the potential of language use as a lens in understanding mental health more generally (Klein and Boals, 2001).

A long line of research has investigated language use in those diagnosed with schizophrenia and many of these studies have assessed EE in caregivers as well (Barrowclough and Hooley, 2003; Brown et al., 1962; Vaughn and Leff, 1976). Caregiver EE captures the attitudes and feelings about their mentally ill family members. This approach involves coding caregiver interviews or speech samples for word usage reflecting criticism, hostility, or emotional over-involvement, as well as perceptions of the quality of their relationships (Magana et al., 1986; Vaughn and Leff, 1976). EE is suggested to predict outcomes including relapse rates in schizophrenia. For example, meta-analytic evidence in schizophrenia suggests that of 27 studies of schizophrenia and EE, caregiver EE was suggested to be a significant predictor of relapse in schizophrenia, with the mean effect size across studies of r = 0.30. Similar to schizophrenia, EE is thought to play an important role in CHR symptomatology (Carol and Mittal, 2015; Domínguez-Martínez et al., 2017; Izon et al., 2018; Mcfarlane and Cook, 2007). For example, a study assessing caregiver EE in those at risk for psychosis (N = 26) was conducted by O’Brien et al. (2006). This group assessed family environment using the Camberwell Family Interview and found that higher levels of emotion over-involvement, positive remarks, and warmth were related to reduced symptoms and improved social functioning 3 months later (effects were in the moderate range). Additionally, from a systematic review conducted by Izon et al. (2018), it was found that of 15 studies of EE in those at risk for psychosis, approximately one third of caregivers had high EE, with greater levels of criticism and hostility relating to symptoms and functioning. Additionally, warmth and family involvement improved symptoms and functioning as well. As suggested from the literature, family environment may have both impactful and protective roles in the context of risk for psychosis. It is important to note that while caregiver language use is suggested to relate to course of mental illness across cultures, caregiver EE levels can vary depending on the culture (Kymalainen and Weisman de Mamani, 2008).

Importantly, while EE has been suggested to perhaps precede or even predict clinical state, it is just as likely that coping with a family members emergence of risk pathology and symptoms may contribute to caregiver burden, which can be expressed through caregiver language use. Increased responsibilities in families with a member experiencing a first-episode of psychosis are well-documented and there is evidence that many family members experience distress and feelings of burden (Addington et al., 2003; Boydell et al., 2014; McCann et al., 2011). Similarly, there is evidence that caregivers of those with a CHR syndrome also report distress (Wong et al., 2008). CHR individuals may begin to experience a decrease in social contact and support (Robustelli et al., 2017), and thus the responsibility may be more heavily carried by family members, which may result in strains in communication (Otero et al., 2011) and difficulties coping with family stress (Yee et al., 2019). Additionally, it is possible challenges faced by caregivers of those with a CHR syndrome may be dominated by worry, in contrast to anger or resentment, given that their family member’s symptoms may be just emerging for the first time.

Automated linguistic analysis is becoming increasingly common across disciplines, including in the study of schizophrenia and CHR groups (Bedi et al., 2015; Cohen et al., 2013; Corcoran et al., 2018; Gupta et al., 2018, 2020; Hamm et al., 2011; Hitczenko et al., 2021), with increasing work focusing on emotional language word usage (e.g., Minor et al., 2015). Especially widely used is Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC; Pennebaker et al., 2015), a user-friendly and efficient computer-based analysis tool that can provide information on a wide variety of linguistic features, including emotional word usage (e.g., indexing the percent of words categorized as affectively positive or negative). The development of LIWC stemmed from Pennebaker and colleagues’ examination of individuals’ personal experiences as expressed through written narratives, and particularly how the ways that people write about aspects of negative life experiences could predict health outcomes (Pennebaker et al., 2003). The linguistic classifications used by LIWC were initially developed by asking independent judges to decide whether a group of 2000 words was related to specific categories, including positive emotion (i.e., laugh) and negative emotion (i.e., sadness). LIWC can also identify words related to specific negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, and sadness. The validity of these linguistic classifications of emotion has been independently validated (Kahn et al., 2007). In contrast to analytic methods relying on trained human coders, LIWC has numerous advantages as it allows for (a) objective analysis and thus improved reliability, (b) evaluation of continuous variables (in contrast to dichotomous yes/no categories), (c) low-cost and efficient, and (d) specificity regarding word categories (e.g., frequencies of words expressing particular emotions).

There exists a growing body of evidence applying LIWC to speech samples in patients with schizophrenia. For example, LIWC has been used to assess word use in social media posts (Mitchell et al., 2015; Zomick et al., 2019), recovery-oriented concepts such as hope in speech samples (Bonfils et al., 2016), brief narratives (Buck and Penn, 2015), and overall word use patterns (Fineberg et al., 2015) in natural speech (Cohen et al., 2009). One study used LIWC to examine the speech of individuals with schizotypy when viewing unpleasant, pleasant, and neutral pictures. Findings from this study indicated those with schizotypy used more negative words when discussing positive images (Najolia et al., 2011). While studies have not assessed caregiver word usage using LIWC in schizophrenia or CHR groups to our knowledge, the current evidence suggests LIWC may be a tool in understanding the interplay between emotional functioning and psychopathology.

1.1. Aims of the study

Given the importance of family environment in understanding psychopathology and the increasing interest in automated analysis in clinical science research, the current study seeks to integrate research on EE and automated linguistic analysis by using LIWC to investigate word usage in caregivers of CHR individuals compared to caregivers of non-CHR controls and measuring relationships with clinical symptoms. Specifically, the present study sought to (a) determine differences in emotional word usage between CHR and control caregivers and (b) identify associations between CHR caregiver emotional word usage and clinical symptoms in individuals at CHR. We also carried out exploratory analyses to assess relationships between LIWC and EE variables (Carol and Mittal, 2015) to investigate areas of potential divergence and convergence in both methodologies. In this previous work examining EE in caregivers of those with a CHR syndrome (Carol and Mittal, 2015), CHR caregivers endorsed fewer initial positive remarks when compared to control caregivers and there were trend level group differences with warmth. Exploratory analyses in the present study are intended to examine whether there are links between positive and negative emotion words derived from LIWC and EE variables from Carol and Mittal (2015; i.e., initial positive remarks and warmth as well as criticism and over-involvement). Drawing from studies of EE showing (a) greater negative word use in caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia and (b) links between caregivers’ negative word use and clinical symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia (Bachmann et al., 2002), we predicted that (a) CHR caregivers would use more negative emotional words compared to controls; and (b) a higher frequency of negative word usage would be related to greater levels of positive, negative, and disorganized symptoms in the CHR group.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 77 adolescents and young adults (CHR = 37, control = 40), aged 13–23 (CHR M = 18.70, SD = 2.15; Control M = 17.55, SD = 2.81) and their family members were recruited through the Adolescent Development and Preventive Treatment (ADAPT) program using email, newspaper, media announcements, Craigslist, and flyers. The exclusion criteria for all adolescent and young adult participants were a history of significant head injury or other physical disorders affecting brain functioning, IQ of less than 70, or history of a substance dependence disorder in the prior 6 months. Additionally, CHR group exclusion criteria included a psychotic disorder diagnosis. Control exclusion criteria included having a first-degree relative with psychosis. CHR group inclusion criteria was determined by the presence of an Attenuated Positive Symptom (APS) or Genetic Risk and Deterioration (GRD) with a decline in functioning (McGlashan et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2003).

Family members were invited to partake in the EE portion of the study. Within the CHR group, 92% of these family members were first-degree relatives (e.g., parents/caregivers), 8% were partner/significant others. In the control group, 85% were first-degree relatives, 10% were partners/significant others and 5% were close friends/second-degree relatives. While all analyses include the listed family members, it is important to note analyses did not change in terms of direction or magnitude when excluding partners/significant others and close friends/second degree relatives. For ease of presentation, we refer to all these family member categories simply as “caregivers”. All participants were consented into the study and all procedures involved received approval by the Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Caregiver emotional word usage

The Five-Minute Speech Sample (FMSS) (Magana et al., 1986) was employed to assess family environment. The FMSS elicits a response from caregivers (note: this may include other relatives as well) and was designed to identify attitudes and feelings about the participant as well as perceptions of the quality of their relationship. After data collection was complete for CHR and control caregiver speech samples, a naïve research assistant transcribed verbatim the audio-recorded speech samples. The FMSS has been used as an alternative to the Camberwell Family Interview for assessing EE (Magana et al., 1986; Malla et al., 1991) and we had initially employed this measure for this purpose. Additional results for a subsection of the present sample that was coded for EE can be found in Carol and Mittal (2015). In the present study, we were primarily interested in determining if LIWC might also be a sensitive measure for detecting emotional word usage in the family environment. For exploratory analyses comparing EE and LIWC, data was used only if a participant had both LIWC and EE data, focusing on available EE variables - initial positive remarks, over-involvement, criticism, warmth. The final subsample for the noted exploratory analyses included 24 CHR and 27 controls.

The transcribed caregiver samples were then submitted into LIWC, a web-based computational language analysis tool. This automated analysis software identifies and processes each word presented in an uploaded text using a dictionary consisting of 6400 words that have been sorted into different categories and structural composition elements. We focused on emotive variable categories. Specifically, to tease apart emotional valence in language use, LIWC provides two general emotional valence categories: (a) positive and (b) negative emotion words. An example of a phrase with positive emotion word usage includes “she is so nice” with the word “nice” counting as a positive emotion word. An example of negative emotion word usage is “her behavior hurt me,” in which the word “hurt” would be considered a negative emotional word. Furthermore, LIWC also identifies words within three more specific negative emotion categories: anxiety (e.g., “nervous,” “tense”), anger (e.g., “hate,” “pissed”), and sadness (e.g., “crying,” “grief”). Note that each instance of a word that counts toward one of these more specific emotion categories (e.g., “grief” for sadness) will also count toward the more general negative emotion category. For all categories, a percent score is calculated by dividing the number of words in that category by the total number of words in the language sample.

2.3. Clinical symptoms in individuals with a CHR syndrome

The Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Syndromes (SIPS) (McGlashan et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2003) was used to detect CHR syndromes and assess symptomatology (positive, negative, disorganized symptoms) in individuals with a CHR syndrome. The Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID, research version) (First, 2014), was used to rule out psychotic disorders and substance dependence. Training of interviewers (who were advanced doctoral students) was conducted over a 2-month period, and inter-rater reliabilities exceed the minimum study criteria of Kappa >0.80.

2.4. Statistical approach

To examine descriptive characteristics and group differences in caregivers’ word usage, we computed independent t-tests and chi-square tests. Linear regression was used to examine whether LIWC variables were associated with symptoms controlling for age. The control group showed low symptoms with minimal variability and therefore we examined LIWC variables and symptom associations within the CHR group alone. To assess for relationships between caregivers’ emotional word usage and CHR symptoms, we fit the data from the CHR caregivers and individuals to a set of linear regression analyses for each symptom category separately. Furthermore, as discussed, exploratory analyses, using point biserial correlations, were conducted examining associations between LIWC and EE variables (initial positive remarks, emotional over-involvement, criticism, and warmth) given that EE variables were dichotomized (see Carol and Mittal, 2015).

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic characteristics

There were no significant differences in biological sex among individuals with a CHR syndrome and controls. Given that linguistic expression can differ between men and women, interaction analyses were conducted in order to examine group (CHR, control) by sex (male, female) predicting LIWC variables; no significant differences were observed, p > 0.38. Furthermore, given the impacts of race and culture on language, an interaction analysis, group (CHR, control) by race predicting LIWC variables, was also employed and no interactions were observed as well, p > 0.13. There was a significant difference in age such that CHR individuals were older than controls. As expected, the CHR group showed significantly more positive, negative, and disorganized symptoms when compared with controls. There were no significant group differences in caregivers’ word count or caregiver education (note: additional caregiver demographic data was unavailable), see Table 1 for demographic details.

Table 1.

Demographic details.

| CHR | Control | Total | Statistic | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant N | 37 | 40 | 77 | ||

| Age | 18.70 (2.15) | 17.55 (2.81) | 18.10 (2.56) | t(75) = 2.03 | 0.048 |

| Biological sex | |||||

| Male | 23 | 19 | 43 | χ2(1) = 1.67 | 0.20 |

| Female | 14 | 21 | 41 | ||

| Total | 37 | 40 | 77 | ||

| Caregiver education | 15.74 (2.58) | 15.84 (2.53) | 15.79 (2.54) | t(75) = −0.16 | 0.87 |

| Race | χ2(1) = 3.94 | 0.56 | |||

| First Nations | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| East Asian | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Black | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Central/South American | 9 | 10 | 19 | ||

| White | 26 | 26 | 52 | ||

| Interracial | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Symptoms | |||||

| Positive symptoms | 11.22 (4.90) | 0.56 (1.35) | 5.75 (6.42) | t(74) = 12.77 | ≤0.001 |

| Negative symptoms | 10.70 (7.52) | 0.33 (0.73) | 5.31 (7.37) | t(74) = 8.35 | ≤0.001 |

| Disorganized symptoms | 5.00 (4.10) | 0.21 (0.47) | 2.54 (3.74) | t(74) = 7.08 | ≤0.001 |

| Word count | 647.05 (131.23) | 714.43 (189.40) | 682.05 (166.48) | t(75) = −1.80 | 0.08 |

Note. These data represent clinical high-risk (CHR) participants except for caregiver education and word count; N = sample size; Age and caregiver education are in years; Caregiver education is the average of mother and father education; Race is represented as counts; Positive, negative, and disorganized symptoms are taken from the Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Syndromes; Word count represents the number of words in the caregiver speech sample.

3.2. Differences in emotional word usage in CHR vs. control caregivers

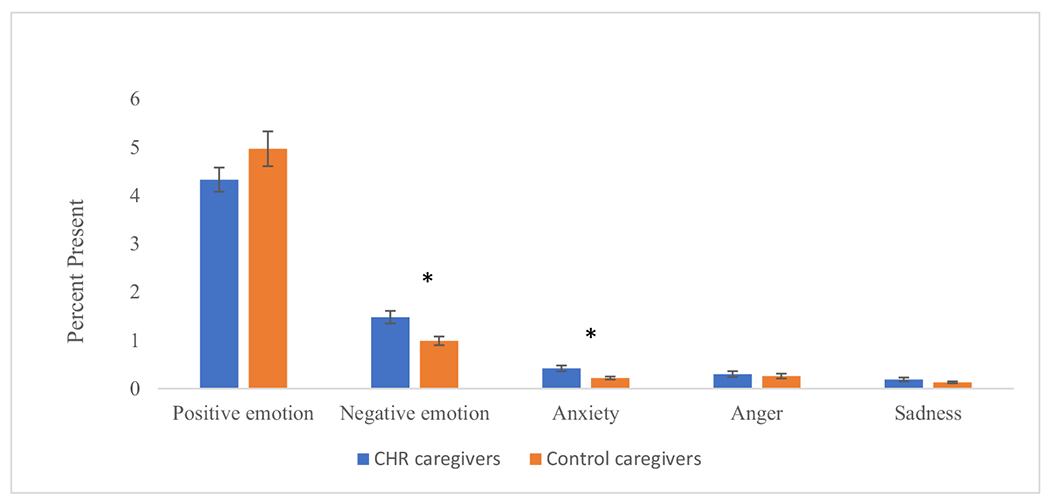

There were no significant group differences in positive emotion words between CHR and control caregivers, F(74) = 1.61, p = 0.21 (Fig. 1). However, there were group differences in negative emotion words, such that CHR caregivers used more negative emotion words compared to control caregivers, F(74) = 12.39, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.14. Analysis of specific types of negative emotion words (i.e., anxiety, anger, sadness) revealed that caregivers of CHR individuals used more words classified as expressing anxiety compared to control caregivers, F(74) = 12.35, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.14. No group differences were observed in the use of anger and sadness words, p > 0.44, see Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Group differences in word use deduced from speech samples submitted into Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count in a sample of caregivers of individuals with a clinical high-risk syndrome (N = 37) compared to control caregivers (N = 40).

Note. *p < 0.05; Anger, sadness, and anxiety are words also counted in the negative emotion category; Error bars represent standard error.

3.3. Associations between CHR caregivers’ emotional word usage and CHR youth’s clinical symptoms

To understand relationships between emotional word use by caregivers and CHR youth’s clinical symptoms, we computed linear regressions that examined how positive and negative emotion word categories as well as anxious, anger, and sadness word use in the caregivers’ speech samples were each separately related to CHR youth’s symptoms. Lower rates of positive emotion words in caregiver speech were significantly related to greater positive symptom scores in the CHR group, F(36) = 4.99, p = 0.013, β = −1.39, t(1,35) = −2.84, p = 0.008 (see Fig. 2), whereas negative emotion word usage (overall negative, anxiety, anger, and sadness words) was not related to positive symptoms, p > 0.28. Findings with positive emotion words remained stable when controlling for EE warmth (see below for analyses with EE variables). There were no significant relationships between LIWC variables and negative or disorganized symptoms, p > 0.64.

Fig. 2.

Relationships between caregivers’ positive emotion word usage and positive symptoms of those with a CHR syndrome (N = 37).

Note. Positive symptoms are a sum scores of items obtained from the Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Syndromes.

3.4. Relationships between automated language analysis and expressed emotion variables within the CHR group

Exploratory analyses revealed more positive emotional words (derived from LIWC) were related to more warmth (derived from EE), r = 0.60, p = 0.03. There were no relationships between initial positive remarks, criticism, and over-involvement and LIWC variables, p > 0.07, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Relationships between Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count and Expressed Emotion Variables within the CHR group (N = 37).

| Positive | Negative | Anger | Sadness | Anxiety | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial positive remarks | 0.22 | 0.006 | −0.08 | 0.95 | 0.11 |

| Criticism | −0.25 | 0.33 | 0.25 | −0.08 | 0.22 |

| Over-involvement | 0.10 | −0.08 | −0.28 | −0.01 | 0.37 |

| Warmth | 0.60* | −0.09 | −0.22 | −0.11 | −0.10 |

Note.

p < 0.05;

Values are point-biserial correlational effect sizes.

4. Discussion

The current study sought to examine emotional word usage among caregivers of CHR individuals to determine differences when compared to control caregivers and links with clinical symptoms. To do this, we applied a linguistic analysis tool (i.e., LIWC) to analyze caregivers’ speech samples as they were talking about their family member (i.e., CHR and control participants). Our findings revealed that caregivers of CHR individuals used more negative words, especially words expressing anxiety, in speech samples when compared to caregivers of non-CHR controls, but there were no differences in general positive emotional word usage, or angry and sadness negative word usage. At the same time, fewer positive emotional words among caregivers were significantly related to greater positive symptomatology among CHR youth (or more positive symptoms were associated with less positive emotion word usage). Lastly, exploratory analyses revealed a positive link between LIWC positive emotional word usage and warmth (but not initial positive remarks, criticism, and over-involvement) from the EE approach within the CHR group. Taken together, these findings support the potential of using LIWC as a means to better understand emotional functioning of caregivers of those at risk for psychosis and detect links with positive symptomatology among those they care for.

Research evidence has long documented heightened negative emotions in caregivers of individuals with psychopathology and schizophrenia specifically (Chan, 2011; Kavanagh, 1992; Stanley et al., 2017), but research on caregivers of those at CHR for psychosis has been relatively sparse to date. Our findings showed that CHR caregivers used more negative emotions words compared to control caregivers, whereas differences in positive emotion words were not significant (although a larger sample might have allowed us to also detect such differences). Analysis of specific negative emotion words in LIWC allowed us to determine that caregiver’s higher negative emotion word usage was driven by more use of anxiety words (e.g., nervous, worried), thus uncovering an important layer of specificity. While anxiety has several definitions, anxiety is often described as a mood state that is future-oriented in nature (Craske et al., 2011). With this, the present findings converge with prior work, which suggests that families/caregivers of individuals with psychosis/risk symptoms endorse more worry (Wong et al., 2008) and may reflect the reality of not just having a child or guardian who experiences attenuated symptoms of psychosis but also the uncertainty about clinical symptom progression and possible conversion to psychosis. This is further bolstered by evidence that caregivers often perceive inpatient visits for family members with psychosis as traumatic (Corcoran et al., 2007). No significant differences were detected in caregivers’ use of words expressing anger or sadness although we should note that both word categories had low base rates. One additional possibility is that perhaps there is not much in the way of EE in CHR caregivers. As mentioned, EE is comprised of overinvolvement and hostility. In this sample, it appeared that caregivers had negative emotion words that were likely driven by anxiety word usage. As such, it may be that levels of EE are potentially lower, if at all present, in those with a CHR syndrome. However, future research is needed before definitive conclusions can be made. Regardless, it is clear that caregivers are impacted and this is useful information when considering the role of caregiver involvement and experiences in mental health.

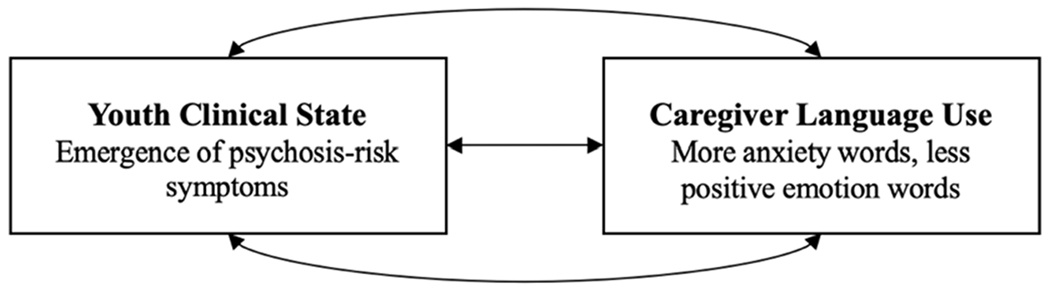

Furthermore, results revealed relationships between lower CHR caregiver positive (but not negative) emotional word usage and positive symptoms among those with a CHR syndrome. These data are difficult to interpret given that caregivers of both the CHR and controls did not show a significant difference in positive emotional words, albeit there is a noticeable pattern of CHR caregivers using fewer positive emotion words. However, when interpreting correlational findings in the context of group differences in caregiver anxiety word usage, it is possible that the emergence of positive symptoms may be contributing to caregiver burden and worry. It is also just as likely that caregiver worry is contributing to a family member’s symptom progression. See Fig. 3 for a possible, bidirectional interpretation of findings highlighting the interplay between CHR symptom severity and caregiver language use.

Fig. 3.

Possible model of the bidirectional relationships between youth clinical state and their caregiver’s language use.

Note. This model posits that the clinical state/symptom severity of a family member can influence their caregiver’s language use (e.g., more anxiety words). However, it is also possible that caregiver language use can influence a family member’s clinical state.

When considering the other direction, higher use of positive emotional words correlated with lower levels of positive symptoms, these findings can be contextualized considering the literature indicating high levels of warmth may be linked with better functional outcomes in patients with schizophrenia and those with a CHR syndrome (O’Brien et al., 2006). This is particularly noteworthy given the findings from exploratory analyses suggested that more LIWC positive emotion words was related to more EE warmth. It is tempting to speculate that positive emotional word use among the CHR caregivers may serve as a protective factor in the development of schizophrenia among those with a CHR syndrome, converging with the noted work on caregiver warmth (O’Brien et al., 2006). Importantly, while we did not find relationships between caregivers’ emotional word usage and negative and disorganized symptoms, it is important to keep in mind that negative or disorganized symptoms are not necessary for a CHR diagnosis. Thus, while existing work has identified important predictors of negative or disorganized symptoms in CHR groups such as postural sway (Dean et al., 2015), caregiver emotional word usage did not appear to be associated in the present study. This may suggest, together, that caregiver word usage and perhaps family environment more broadly may have unique links with positive symptoms in particular, which are central to a CHR syndrome diagnosis.

Exploratory analyses investigating relationships between LIWC emotion words and EE variables suggest that LIWC can be a useful tool to assess for emotional functioning of caregivers that extends beyond the traditional EE categories. Of the EE categories examined in line with our previous work (initial positive remarks, criticism, over-involvement, and warmth), we only identified a positive association between LIWC positive emotional word usage and EE warmth. As mentioned, in Carol and Mittal (2015), there was a trend level difference in warmth between CHR caregivers and control caregivers. As such, it is not surprising that we see links in this study between positive emotional word usage and EE warmth and this is further supported by the notion that EE warmth is a more specific category including a more limited range of emotions and attitudes (e.g. warmth: “My kid is a very kind person.”). Overall, this finding suggests some convergent validity with the EE approach. However, we did not see links between LIWC positive (or negative) emotional word usage and initial positive remarks, criticism, and over-involvement. In Carol and Mittal (2015), fewer initial positive remarks were found in caregivers of CHR individuals when compared to control caregivers. Thus, it is unexpected that there were no links between LIWC positive word use and initial positive remarks. However, given LIWC was applied to the whole passage (instead of the first few remarks), that may be one way to explain this area of divergence. Furthermore, lack of relationships between LIWC and EE criticism and over-involvement may be due the fact that these are complex categories that are not defined by discrete emotion categories but instead are attitudes and behaviors based (Magana et al., 1986; e.g. emotional over-involvement: “I would do absolutely anything to make sure my daughter is always safe.”; criticism: “It feels like we have always had issues with my son.”). Therefore, the pattern of divergence between negative LIWC and EE variables in particular suggest that LIWC may be picking up on unique aspects of emotional word usage that perhaps go beyond the EE categories such as what is observed with our findings with LIWC anxiety words. The level of specificity offered by LIWC may be particularly relevant for assessing CHR caregivers’ emotional functioning given the differences between this period of emerging symptoms compared to the acuity of symptoms and family functioning observed after the onset of schizophrenia.

These data have preliminary clinical implications that serve as a foundation for future research. Importantly, these data suggest that there may be utility in implementing treatment modalities that provide support for both the individual experiencing symptoms but also for the ones that care for them. Furthermore, if caregivers are experiencing more anxiety as a result of learning about new CHR symptoms or perhaps as a consequence of caring for one with symptoms, there may be utility in emphasizing CHR psychoeducation at several instances across the course of treatment so that caregivers gain knowledge and an understanding of symptoms. With this, this knowledge can be translated to situations that occur outside of the treatment setting. In schizophrenia, family psychoeducation and involvement has been found to be useful in reducing relapse rates and improving family wellbeing (McFarlane et al., 2003). In studies of those with a CHR syndrome, there is evidence that family therapies, such as family focused therapy (FFT) may be effective as well (Marvin et al., 2016; Miklowitz et al., 2014). It will be critical to continue to unravel the impacts of family environment on CHR symptoms with the goal of refining possible targets (e.g., caregiver anxiety) and as a result, more effectively apply interventions.

While there are several strengths of this study (e.g., the use of LIWC, the comparison of CHR caregivers with controls), there are limitations to consider. First, in the present study we used FMSS in order to assess for family environment; however, this is only one aspect of family environment and there may be other components (such as tolerance of familial stress, social support etc.) in more naturalistic settings that we may be missing. Additionally, this approach involves asking caregivers to speak about their family members rather than speaking to their family members in a conversation. Future research using dyadic interaction could be useful to understand language use in these contexts. Second, the present study was cross-sectional. Longitudinal studies are needed to reveal whether emotional word usage in caregivers predict clinical course in CHR individuals over time. Third, the present study focused on LIWC emotion variables, but LIWC provides several other variables that may be informative in understanding other components related to the etiology of schizophrenia. Furthermore, there may be additional emotion words that are not captured by LIWC that could be detected by other linguistic approaches and this should be examined in additional research. An additional point is that LIWC employs an approach that examines single word usage without considering the context of a situation. As such, additional natural language processing approaches may be useful to investigate in future work that considers context more fully. In the future, it will also be beneficial to investigate differences between automated and human coder approaches in order to truly understand unique contributions each may have to studying emotion language and health outcomes more broadly. Fourth, there may be biases in automated approaches as such in terms of race, ethnicity, culture, and sex (Hitczenko et al., 2021). One of the benefits of LIWC is the focus on word count/category. However, with this, there may be contextual pieces of information related to race, ethnicity, culture, and sex that may be lost that could have been useful to consider in our understanding of language analysis. Future work is needed to further understand these possible relationships. Fifth, while the majority of our caregiver sample were first-degree relatives and parental education was reported, there were several other demographic details that were not available. It will be critical to better characterize caregivers in future studies. Furthermore, it will be useful to examine what aspect of caregiver positive word usage (with warmth being a key candidate) drives this link with positive symptoms. Other ideas for future directions include continuing to understand the role of family coping and environment throughout the process of identification, detection, and intervention in early psychosis. Furthermore, it will be useful to examine what aspect of caregiver positive word usage (with warmth being a key candidate) drives this link with positive symptoms.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01MH094650, R21/R33MH103231, R21MH119677 to V.A.M, a National Institute of Mental Health Grant R21MH115231 to C.M.H. and V.A.M, and a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation to C.M.H.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dr. Mittal attained funding and oversaw data collection. All co-authors helped to conceptualize the study, interpret results, and draft/edit the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

References

- Addington J, Coldham EL, Jones B, Ko T, Addington D, 2003. The first episode of psychosis: the experience of relatives. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 108, 285–289. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann S, Bottmer C, Jacob S, Kronmüller K-T, Backenstrass M, Mundt C, Renneberg B, Fiedler P, Schröder J, 2002. Expressed emotion in relatives of first-episode and chronic patients with schizophrenia and major depressive disorder—a comparison. Psychiatry Res. 112, 239–250. 10.1016/S0165-1781(02)00226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrowclough C, Hooley JM, 2003. Attributions and expressed emotion: a review. Clin. Psychol. Rev 23, 849–880. 10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi G, Carrillo F, Cecchi GA, Slezak DF, Sigman M, Mota NB, Ribeiro S, Javitt DC, Copelli M, Corcoran CM, 2015. Automated analysis of free speech predicts psychosis onset in high-risk youths, 1, 15030. 10.1038/npjschz.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfils KA, Luther L, Firmin RL, Lysaker PH, Minor KS, Salyers MP, 2016. Language and hope in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. 245, 8–14. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boydell J, Onwumere J, Dutta R, Bhavsar V, Hill N, Morgan C, Dazzan P, Morgan K, Pararajan M, Kuipers E, Jones P, Murray R, Fearon P, 2014. Caregiving in first-episode psychosis: social characteristics associated with perceived ‘burden’ and associations with compulsory treatment. Early Interv. Psychiatry 8, 122–129. 10.1111/eip.12041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Monck EM, Carstairs GM, Wing JK, 1962. Influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic illness. Br. J. Prev. Soc. Med 16, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Buck B, Penn DL, 2015. Lexical characteristics of emotional narratives in schizophrenia: relationships with symptoms, functioning, and social cognition. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 203, 702–708. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carol EE, Mittal VA, 2015. Resting cortisol level, self-concept, and putative familial environment in adolescents at ultra high-risk for psychotic disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 57, 26–36. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SW, 2011. Global perspective of burden of family caregivers for persons with schizophrenia. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs 25, 339–349. 10.1016/j.apnu.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, St-Hilaire A, Aakre JM, Docherty NM, 2009. Understanding anhedonia in schizophrenia through lexical analysis of natural speech. Cognit. Emot 23, 569–586. 10.1080/02699930802044651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, Morrison SC, Callaway DA, 2013. Computerized facial analysis for understanding constricted/blunted affect: initial feasibility, reliability, and validity data. Schizophr. Res 148, 111–116. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran C, Gerson R, Sills-Shahar R, Nickou C, McGlashan T, Malaspina D, Davidson L, 2007. Trajectory to a first episode of psychosis: a qualitative research study with families. Early Interv. Psychiatry 1, 308–315. 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran CM, Carrillo F, Fernández-Slezak D, Bedi G, Klim C, Javitt DC, Bearden CE, Cecchi GA, 2018. Prediction of psychosis across protocols and risk cohorts using automated language analysis. World Psychiatry 17, 67–75. 10.1002/wps.20491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Rauch SL, Ursano R, Prenoveau J, Pine DS, Zinbarg RE, 2011. What is an anxiety disorder? Focus J. Lifelong Learn. Psychiatry 20. [Google Scholar]

- Dean DJ, Kent JS, Bernard JA, Orr JM, Gupta T, Pelletier-Baldelli A, Mittal VA, 2015. Increased postural sway predicts negative symptom progression in youth at ultrahigh risk for psychosis. Schizophrenia Res. 162 (1-3), 86–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Martínez T, Medina-Pradas C, Kwapil TR, Barrantes-Vidal N, 2017. Relatives’ expressed emotion, distress and attributions in clinical high-risk and recent onset of psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 247, 323–329. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg SK, Deutsch-Link S, Ichinose M, McGuinness T, Bessette AJ, Chung CK, Corlett PR, 2015. Word use in first-person accounts of schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry 206, 32–38. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.140046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, 2014. Structured clinical interview for the DSM (SCID). In: The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fung CK, Moore MM, Karcher NR, Kerns JG, Martin EA, 2017. Emotional word usage in groups at risk for schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: an objective investigation of attention to emotion. Psychiatry Res. 252, 29–37. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fussell SR, 2002. How to do emotions with words: emotionality in conversations. In: The Verbal Communication of Emotions. Psychology Press, pp. 87–114. 10.4324/9781410606341-10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta T, Hespos SJ, Horton WS, Mittal VA, 2018. Automated analysis of written narratives reveals abnormalities in referential cohesion in youth at ultra high risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Res 192, 82–88. 10.1016/j.schres.2017.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta T, Haase CM, Strauss GP, Cohen AS, Ricard JR, Mittal VA, 2020. Alterations in facial expressions of emotion: determining the promise of ultrathin slicing approaches and comparing human and automated coding methods in psychosis risk. Emotion. 10.1037/emo0000819. No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm J, Kohler CG, Gur RC, Verma R, 2011. Automated facial action coding system for dynamic analysis of facial expressions in neuropsychiatric disorders. J. Neurosci. Methods 200, 237–256. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitczenko K, Cowan HR, Goldrick M, Mittal VA, 2021. Racial and ethnic biases in computational approaches to psychopathology. Schizophr. Bull, sbab131 10.1093/schbul/sbab131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, 1985. Expressed emotion: a review of the critical literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev 5, 119–139. 10.1016/0272-7358(85)90018-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Izon E, Berry K, Law H, French P, 2018. Expressed emotion (EE) in families of individuals at-risk of developing psychosis: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 270, 661–672. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JH, Tobin RM, Massey AE, Anderson JA, 2007. Measuring emotional expression with the linguistic inquiry and word count. Am. J. Psychol 120, 263–286. 10.2307/20445398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh DJ, 1992. Recent developments in expressed emotion and schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry 160, 601–620. 10.1192/bjp.160.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein K, Boals A, 2001. Expressive writing can increase working memory capacity. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen 130, 520–533. 10.1037/0096-3445.130.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers L, Bebbington P, 1988. Expressed emotion research in schizophrenia: theoretical and clinical implications. Psychol. Med 18, 893–909. 10.1017/S0033291700009831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kymalainen JA, Weisman de Mamani AG, 2008. Expressed emotion, communication deviance, and culture in families of patients with schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol 14, 85–91. 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist KA, Satpute AB, Wager TD, Weber J, Barrett LF, 2016. The brain basis of positive and negative affect: evidence from a meta-analysis of the human neuroimaging literature. Cereb. Cortex 26, 1910–1922. 10.1093/cercor/bhv001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magana AB, Goldstein J, Karno M, Miklowitz D, Jenkins J, Falloon I, 1986. A brief method for assessing expressed emotion in relatives of psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Res. 17, 203–212. 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malla AK, Razarian SS, Barnes S, Cole JD, 1991. Validation of the five minute speech sample in measuring expressed Emotion*. Can. J. Psychiatr 36, 297–299. 10.1177/070674379103600411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin SE, Miklowitz DJ, O’Brien MP, Cannon TD, 2016. Family-focused therapy for individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: treatment fidelity within a multisite randomized trial. Early Interv. Psychiatry 10, 137–143. 10.1111/eip.12144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann TV, Lubman DI, Clark E, 2011. First-time primary caregivers’ experience of caring for young adults with first-episode psychosis. Schizophr. Bull 37, 381–388. 10.1093/schbul/sbp085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcfarlane WR, Cook WL, 2007. Family expressed emotion prior to onset of psychosis. Fam. Process 46, 185–197. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane WR, Dixon L, Lukens E, Lucksted A, 2003. Family psychoeducation and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. J. Marital. Fam. Ther 29, 223–245. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Miller TJ, Woods SW, Rosen JL, Hoffman RE, Davidson L, 2001. Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes. PRIME Research Clinic, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT. [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, O’Brien MP, Schlosser DA, Addington J, Candan KA, Marshall C, Domingues I, Walsh BC, Zinberg JL, De Silva SD, Friedman-Yakoobian M, Cannon TD, 2014. Family-focused treatment for adolescents and young adults at high risk for psychosis: results of a randomized trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 53, 848–858. 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead K, Ventura J, McFarlane W, Perkins DO, Pearlson GD, Woods SW, 2003. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr. Bull 29, 703–715. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor KS, Bonfils KA, Luther L, Firmin RL, Kukla M, MacLain VR, Buck B, Lysaker PH, Salyers MP, 2015. Lexical analysis in schizophrenia: how emotion and social word use informs our understanding of clinical presentation. J. Psychiatr. Res 64, 74–78. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell M, Hollingshead K, Coppersmith G, 2015. Quantifying the language of schizophrenia in social media. In: Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology: From Linguistic Signal to Clinical Reality. Association for Computational Linguistics, Denver, Colorado, pp. 11–20. 10.3115/v1/W15-1202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Najolia GM, Cohen AS, Minor KS, 2011. A laboratory study of affectivity in schizotypy: subjective and lexical analysis. Psychiatry Res. 189, 233–238. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MP, Gordon JL, Bearden CE, Lopez SR, Kopelowicz A, Cannon TD, 2006. Positive family environment predicts improvement in symptoms and social functioning among adolescents at imminent risk for onset of psychosis. Schizophrenia Research 81 (2-3), 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero S, Moreno-Iniguez M, Payá B, Castro-Fornieles J, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Baeza I, Arango-López C, 2011. Twelve-month follow-up of family communication and psychopathology in children and adolescents with a first psychotic episode (CAFEPS study). Psychiatry Res. 185 (1-2), 72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Mehl MR, Niederhoffer KG, 2003. Psychological aspects of natural language use: our words, our selves. Annu. Rev. Psychol 54, 547–577. 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Boyd RL, Jordan K, Blackburn K, 2015. The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC2015 26. [Google Scholar]

- Robustelli BL, Newberry RE, Whisman MA, Mittal VA, 2017. Social relationships in young adults at ultra high risk for psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 247, 345–351. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley S, Balakrishnan S, Ilangovan S, 2017. Psychological distress, perceived burden and quality of life in caregivers of persons with schizophrenia. J. Ment. Health 26, 134–141. 10.1080/09638237.2016.1276537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tausczik YR, Pennebaker JW, 2010. The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol 29, 24–54. 10.1177/0261927X09351676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn C, Leff J, 1976. The measurement of expressed emotion in the families of psychiatric patients. Br. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol 15, 157–165. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1976.tb00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C, Davidson L, McGlashan T, Gerson R, Malaspina D, Corcoran C, 2008. Comparable family burden in families of clinical high-risk and recent-onset psychosis patients. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2, 256–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee CI, Gupta T, Mittal VA, Haase CM, 2019. Coping with family stress in individuals at clinical high-risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Res 10.1016/j.schres.2019.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zomick J, Levitan SI, Serper M, 2019. Linguistic analysis of schizophrenia in Reddit posts. In: Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology. Association for Computational Linguistics, Minneapolis, Minnesota, pp. 74–83. 10.18653/v1/W19-3009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]