Abstract

In the United States (US), private-supply tapwater (TW) is rarely monitored. This data gap undermines individual/community risk-management decision-making, leading to an increased probability of unrecognized contaminant exposures in rural and remote locations that rely on private wells. We assessed point-of-use (POU) TW in three northern plains Tribal Nations, where ongoing TW arsenic (As) interventions include expansion of small community water systems and POU adsorptive-media treatment for Strong Heart Water Study participants. Samples from 34 private-well and 22 public-supply sites were analyzed for 476 organics, 34 inorganics, and 3 in vitro bioactivities. 63 organics and 30 inorganics were detected. Arsenic, uranium (U), and lead (Pb) were detected in 54%, 43%, and 20% of samples, respectively. Concentrations equivalent to public-supply maximum contaminant level(s) (MCL) were exceeded only in untreated private-well samples (As 47%, U 3%). Precautionary health-based screening levels were exceeded frequently, due to inorganics in private supplies and chlorine-based disinfection byproducts in public supplies. The results indicate that simultaneous exposures to co-occurring TW contaminants are common, warranting consideration of expanded source, point-of-entry, or POU treatment(s). This study illustrates the importance of increased monitoring of private-well TW, employing a broad, environmentally informative analytical scope, to reduce the risks of unrecognized contaminant exposures.

Keywords: tapwater, arsenic, organics, inorganics, human health, private wells, underserved communities

Short abstract

Elevated human risk from co-occurring inorganic and organic contaminants observed in public and private tapwater in United States tribal lands.

1. Introduction

Water is life (Mní wičhóni in Lakota). The quality and sustainability of drinking water are growing challenges in the United States (US) and world wide due to, among other reasons, increasing water demands and drinking-water source contamination.1−3 US public, private, and bottled drinking-water supplies share many anthropogenic-contaminant (i.e., human-generated/-driven) concerns, because most of the 350,000 chemicals estimated to be in commercial use globally4 and, by extension, potentially in drinking-water source waters5,6 are not currently regulated or systematically monitored in public-supply tapwater (TW)7,8 or in bottled drinking water.9 Note, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) does not regulate private wells nor does it provide recommended criteria or standards for individual wells.10 In contrast, many water-borne pathogens (e.g., Cryptosporidium) and naturally occurring contaminants (e.g., arsenic, As) are actively regulated in US public and bottled-water supplies.7−9

The potential for unrecognized contaminant exposures and adverse health effects is notably elevated for private and small community drinking-water supplies in rural and remote areas,11,12 due to differences in regulation, technical expertise, natural/economic resources, and associated risk-management options.13−15 Although some geogenic groundwater contaminants, such as As, exhibit broadly predictive geospatial patterns,16,17 individual point-of-use (POU) TW concentrations reflect multiple factors including well-screen/open-hole depth, geologic stratigraphy, and spatial/temporal variability in water levels and redox conditions and, consequently, can differ substantially and unpredictably from well to well.18,19 Further, As and several other contaminants are imperceptible (tasteless and odorless) without TW testing.11,12,20

Prior studies have documented a range of contaminant concerns in unregulated drinking water.12,20,21 Due to high analytical costs, common-place conflation of organoleptic quality with safety, and other socioeconomic factors, private-well water-quality data remain scarce and, where available, are typically limited to a few targeted contaminants.20−23 Similarly, small rural water systems are often concerns for various socioeconomic reasons, including financial limitations of smaller and lower-income populations.24−27 The elevated probability of unrecognized exposures has prompted calls for universal private-well As testing,23,28 but, acknowledging the increasingly human-impacted water cycle,29,30 broader characterization of private-well and rural-water-system contaminant exposures is needed.31

The Strong Heart Study (SHS) is an ongoing population-based prospective-cohort study of cardiovascular disease and associated risk factors among American Indian (AI) adults in participating Tribal Nations in Arizona, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and South Dakota.32 Groundwater As varies regionally across the US, with elevated concentrations predicted and observed16,17,33,34 throughout SHS areas. SHS research has associated low to moderate drinking-water As exposures with lung, prostate, and pancreatic cancer,35 cardiovascular disease,36 kidney disease,37 lung disease,38 and type-2 diabetes outcomes.39,40 Efforts to manage As-related health risks in SHS-area TW include the development/expansion of rural water systems and the Strong Heart Water Study (SHWS), a participatory randomized controlled intervention to reduce As exposures in remote residences in North and South Dakota using undersink adsorptive-media POU treatment.41,42

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) collaborates with EPA, the National Institute of Environmental Health Science (NIEHS), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Tribal Nations, universities, utilities, communities, and others to inform drinking-water exposure and water-supply data gaps by assessing TW inorganic/organic contaminant mixtures and associated distal (e.g., ambient source water) and proximal (e.g., premise plumbing and POU treatment) drivers in a range of socioeconomic and source-water vulnerability settings across the US.29,30,43,44 As part of that ongoing effort, we assessed exposures to a broad suite of potential inorganic and organic TW contaminants in 56 homes in three areas of North Dakota and South Dakota in 2019 to provide insight into cumulative contaminant risk to human health45−47 of private-well and small community public-supply TW in this region, to assess the utility of broader TW contaminant assessments for identifying additional risk management efficiencies in areas undergoing drinking-water interventions for As, and to expand the national perspective on inorganic and organic contaminant exposures at the TW point of use by maintaining the same general sampling protocol and analytical toolbox employed in previous studies.29,30,43,44

For this study, TW exposure was operationally represented as concentrations of 476 organics, 34 inorganics, and 3 bioactivity indicators in residential and community POU TW samples. Potential human-health risks of individual and aggregate TW exposures were explored based on cumulative detections/concentrations of designed-bioactive chemicals (e.g., pesticides and pharmaceuticals),5 as well as the cumulative exposure-activity ratio(s) (ΣEAR)48 and hazard indices (HI)49,50 of cumulative benchmark-based toxicity quotient(s) (TQ) (ΣTQ).51 In line with previous results by this research group and others, simultaneous TW exposures to multiple inorganic and organic constituents of potential human-health interest were hypothesized to occur in both private- and public-supply samples.12,21,29,30

2. Methods

2.1. Site Selection and Sample Collection

Sample locations were selected from community volunteers to provide broad spatial coverage of private-/public-supply TW in three Tribal areas in North Dakota and South Dakota,41 with 16 private; 10 private/10 public; and 8 private/12 public TW locations from communities A, B, and C, respectively (Figures 1 and S1). All community A locations were SHWS participants, for which the inclusion criterion was greater than maximum contaminant level(s) (MCL) baseline TW As concentrations. In this study, all private-supply and 15 public-supply TW samples were groundwater sourced. In community B, three and seven public-supply sample locations were connected to groundwater-sourced and surface-water-sourced (Missouri River) water systems, respectively. Community C public-supply samples were groundwater sourced, with 11 samples from the primary, multiwell water system and one sample from a small (65 people) system. In general, TW samples were collected from untreated kitchen faucets, except for four (three private, one public) community B samples collected from POU-treatment taps (denoted POU-AF in Supporting Information Tables) at the participants’ request. One other TW-sample location (community B) had a point-of-entry water-softener system (POE-S in Supporting Information Tables).

Figure 1.

Cumulative (sum of all detected) concentrations (μg L–1) and numbers of organic compounds in samples of public-supply (diamonds, ◆) and private-supply (circles, ●) TW collected during 2019 in North Dakota and South Dakota. Sample locations are anonymized.

Taps (cold water) were sampled once each from September to November 2019. Samples were collected at the participant’s convenience throughout the day, without precleaning, screen removal, or Lead and Copper Rule stagnant-sample protocols.52,53 Complete sampling details are provided elsewhere.54−56

2.2. Methods and Quality Assurance

Briefly, TW samples were analyzed by USGS using seven organic (6 classes; 476 total/468 unique analytes), five inorganic (34 ions/trace elements), and two field (3 parameters) methods (Table S2) and by USEPA using three in vitro bioassay (ER, AR, and GR) methods, as discussed29,30,43,54 and described in detail previously.57−74 Organic analytes included cyanotoxin, disinfection byproduct(s) (DBP), pesticide, per/polyfluoroalkyl substance(s) (PFAS), volatile organic compound(s) (VOC), and pharmaceutical classes; additional method details are in the Supporting Information. All results are in Tables S3–S4 and S8 and in Romanok et al.55,56 Quantitative (≥limit of quantitation, ≥LOQ) and semiquantitative (between LOQ and long-term method detection limit, MDL75,76) results were treated as detections.75,77,78 Quality-assurance/quality-control included analyses of six field blanks, as well as laboratory blanks, spikes, and stable-isotope surrogates. Only bromide was detected in inorganic blanks at concentrations in the range observed in TW samples; results were censored at the maximum blank concentration (0.14 mg L–1), as footnoted (Tables S3 and S5). Among detected organics, only ethyl acetate (0.14 μg L–1) was detected in a blank (1) in the concentration range observed in TW samples; results were censored at two times the maximum blank concentration (0.28 μg L–1), as footnoted (Tables S4 and S6). The median surrogate recovery (Table S7) was 99.9% (interquartile range: 89–110%)

2.3. Statistics and Risk Assessments

Differences between TW-sample groups were assessed by nonparametric one-way PERMANOVA (n = 9999 permutations) on Euclidean distance (Paleontological Statistics, PAST, vers. 4.03).79 Relations between detected TW contaminants were assessed by Spearman rank-order correlation (ρ) and permuted (n = 9999) probabilities (PAST, vers. 4.03).79

Screening-level assessments49,50 of potential cumulative effects were based on the cumulative exposure-activity ratio(s) (ΣEAR)48 and HI49,50,80 of cumulative benchmark-based TQ (ΣTQ),51 as described.29 ToxEval version 1.2.081 of R82 was used to sum (noninteractive concentration addition model83−85) individual ToxCast-based86,87 exposure activity ratios (EAR) or benchmark-based TQ, respectively. For the latter, the most protective human-health benchmark (i.e., lowest benchmark concentration) among MCL goal(s) (MCLG),7,88 WHO guideline values (GV) and provisional GV,89 USGS Health-Based Screening Level (HBSL),90 and state drinking-water MCL or health advisories (DWHA) was used. MCLG values of zero (i.e., no identified safe-exposure level for sensitive subpopulations, including infants, children, the elderly, and those with compromised immune systems and chronic diseases7,91) were set equal to the method reporting limit or 1 μg L–1 for lead (Pb).92 Cumulative EAR (ΣEAR) and TQ (ΣTQ) results, ToxCast exclusions, and health-based benchmarks are summarized in Tables S9–S13 (additional details in Supporting Information).

3. Results and Discussion

Regulated and unregulated chemicals (inorganic, organic) were detected in TW samples in all three study areas (Tables 1, S3, and S4; Figures 1–4), with two or more detections of human-health interest commonly observed per sample. 63 (14%) organic and 30 (91%) inorganic analytes were detected. In this discussion, the enforceable EPA MCL or, for Pb, action level (AL) for technology treatment is provided from a regulatory perspective, but the organ/organism-level human-health effects of individual contaminant exposures are contextualized based on MCLG and human-health advisories, for three reasons. First, EPA MCL and AL are enforceable in public supplies7,8 but not in private supplies.10 Second, MCL and AL are set as close to MCLG values as feasible but are often higher to reflect technical and financial constraints of drinking-water monitoring and treatment.91 Last, MCLG and health advisory values generally include a margin of exposure to provide a safety threshold, in the case of MCLG defined as the concentration below which there is no known risk to the health of presumptive “most vulnerable” (e.g., infants, children, pregnant women, elderly, and immune-compromised) subpopulations.91

Table 1. Number of Exceedances of Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) Concentrations (MCL-Equivalent for Private Well Locations) or Listed Health GVs Observed in TW Samplesa.

| public

supply |

private wells |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| class | constituent | guidancea | value | community B (N = 10) | community C (N = 12) | community A (N = 16) | community B (N = 10) | community C (N = 8) |

| inorganic | arsenic | MCL | 10 μg/L | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 3 |

| MCLG | 0 μg/L | 0 | 11 | 15 | 0 | 4 | ||

| lead | AL | 15 μg/L | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| MCLG | 0 μg/L | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | ||

| manganese | DWHA | 300 μg/L | 0 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 7 | |

| nitrate | MCL(MCLG) | 10 mg/L | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| selenium | MCL(MCLG) | 50 μg/L | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vinceti et al.134 | 1 μg/L | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | ||

| uranium | MCL | 30 μg/L | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| MCLG | 0 μg/L | 2 | 0 | 15 | 3 | 4 | ||

| organic | atrazine | MCL(MCLG) | 3 μg/L | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EU Directive | 0.1 μg/L | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| benzene | MCLG | 0 μg/L | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| bromodichloromethane | MCLG | 0 μg/L | 9 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| dichloromethane | MCLG | 0 μg/L | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1,2-dichloropropane | MCLG | 0 μg/L | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| tribromomethane | MCLG | 0 μg/L | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TCE | MCLG | 0 μg/L | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| vinyl chloride | MCLG | 0 μg/L | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Figure 4.

Individual (circles, ●) and cumulative (sum of all detected; red triangles, ▲) concentrations of organic analytes detected in public-supply (shaded) and private-supply (unshaded) TW samples collected during 2019 in North Dakota and South Dakota. Boxes, centerlines, and whiskers indicate interquartile range, median, and 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively. Numbers above each boxplot indicate total detected organic analytes. “nd” indicates not detected.

Figure 3.

Detected concentrations (μg L–1) and the number of sites (right axis) for 63 organic analytes (left axis, in order of decreasing total detections) detected in TW samples collected during 2019 in North Dakota and South Dakota. Circles are data for individual samples. Boxes, centerlines, and whiskers indicate interquartile range, median, and 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively.

3.1. TW Arsenic, Uranium, and Lead

Consistent with previous reports,33,34,41,93 TW exposures to As, U, and Pb, which have no known safe level of drinking-water exposure for vulnerable sub-populations (MCLG zero), were widely observed (54, 43, and 20% of samples, respectively) in the three study areas in private- and public-supply locations (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Concentrations (circles, ●) of select inorganics detected during 2019 in North Dakota and South Dakota in public-supply (shaded) and private-supply (unshaded) TW samples within three study areas. Solid red lines indicate public-supply enforceable maximum contaminant level(s) (MCL) or technology treatment action level (Pb). MCL goals (MCLG) for As, U, and Pb are zero. The solid purple line indicates the Mn lifetime drinking water health advisory. Boxes, centerlines, and whiskers indicate interquartile range, median, and 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively. Numbers above each boxplot pair indicate the permuted probability that the centroids and dispersions are the same (PERMANOVA; 9999 permutations). “nd” indicates not detected.

In line with earlier SHWS findings,41 the redox-reactive geogenic contaminant As was consistently detected (MCLG exceedance) in communities A and C (94 and 75% of samples, respectively), but not in community B. Consistent with the SHWS inclusion criterion, As was detected in all but one community A sample, near (9 μg L–1 in three samples) or above (11 samples) MCL-equivalent concentrations in 88% (14/16) of samples. In community C, As was detected in 50% (4/8) and 92% (11/12) of private- and public-supply samples, respectively, but MCL-equivalent exceedances occurred only in three private-well locations. Overall, the results support ongoing expansions/connections to public supplies as an effective approach to limit TW As-exposures to <MCL concentrations in these communities and POU/POE treatment41,42 in private-supply locations where a public-supply connection is not feasible. The results emphasize the potential for unrecognized exposures to contaminants, including contaminants of human-health concern, in unregulated/unmonitored private supplies and support private-well As monitoring.23,28,33 The results also support the potential use of POU/POE treatment at public-supply locations with detectable As, as an additional As removal step. While As-associated Safe Drinking Water Information System (SDWIS) violations,94 As concentrations, and urinary As levels95,96 associated with public supplies have decreased substantially since the MCL was lowered, no safe level of TW As exposure is recognized for vulnerable subpopulations.97 Drinking water As exposure is associated with various cancers,98,99 organ-system toxicity,98 cardiovascular diseases,100,101 diabetes,100,101 adverse pregnancy outcomes,102 and mortality.102,103 Adverse health associations with <MCL As exposures35,98,100,104 have prompted a 5 μg L–1 MCL in some US states (e.g., New Jersey and New Hampshire105,106). Every private-well sample with detectable As and 92% of community C public-supply samples exceeded 5 μg L–1.

Also, consistent with previous findings,34,93 the redox-reactive geogenic radionuclide U was detected (MCLG exceedance) in all three communities (A: 94%, B: 25%, and C: 20%). Drinking-water U is associated with nephrotoxicity107,108 and osteotoxicity109 in humans, inhibition of DNA-repair mechanisms in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells,110 and estrogen-receptor effects in mice.111 The MCL-equivalent concentration was exceeded only in one private-well location. Community C U exposures differed (PERMANOVA, p = 0.013) between private- (4 detections) and public-supply (no detections) locations. No difference was apparent in community B (p = 0.93), with 2–3 detections (≤6 μg L–1) each in private-well and public-supply samples. Other widely documented, drinking-water radionuclides (e.g., radium and radon)6,21 not assessed herein should be included in future assessments.

As and U co-occurred in 16 (42%) of the 38 samples in which either was detected and were moderately positively correlated (Spearman ρ = 0.48, permutation [n = 9999] p = 0.0002). Because groundwater As and U are favored under reducing and oxidizing conditions, respectively, frequent co-occurrence in SHWS well water suggests redox heterogeneity is common34 or redox-independent mechanisms (e.g., pH/alkalinity-driven solubility) are important.93 Elevated iron (Fe) and manganese (Mn) concentrations in oxic TW herein support the former. A moderate correlation (ρ ≥ 0.42; p < 0.0001) between U and nitrate (NO3) was reported112 for the High Plains aquifer, the northern extension of which underlies community A; a weaker correlation (ρ ≥ 0.27; p < 0.042) was observed herein.

Pb was detected sporadically (20% of samples) in private- and public-supply locations in all communities but did not exceed the AL-equivalent concentration. Elevated drinking-water Pb-exposures primarily are associated with neurocognitive impairment in infants and children.92,113 The American Academy of Pediatrics92 recommends that drinking-water Pb not exceed 1 μg L–1, a common MDL for US public-supply compliance monitoring.52 Drinking-water Pb is attributed primarily to premise-plumbing and distribution-infrastructure materials113 that predate the 1986 SDWA Amendments.114 In this study, no difference in Pb detections (p ≥ 0.11) between private- and public-supplies and no systematic Pb detections within a given public-supply system support premise plumbing as the probable source. Importantly, the current results likely underestimate TW Pb occurrence and concentrations in the study area, because flushing effectively decreases plumbing-derived contaminant concentrations,113,115 and same-day prior TW use was common in this study.

3.2. TW Nitrate

TW nitrate–nitrogen (NO3–N) concentrations were generally low (median: 0.4 mg L–1) in the study area, with elevated (>2 mg L–1) concentrations, including one MCL-equivalent exceedance (Table 1), observed infrequently (4 samples) and only in private-well locations. No co-contaminants (e.g., human-use pharmaceuticals) indicative of human-waste sources (e.g., septic systems) were detected in elevated NO3–N samples, indicating other sources, such as inorganic/organic crop fertilizers or animal wastes, as possible contributors to elevated TW NO3–N concentrations; the lack of detectable pesticides in the four TW samples with >2 mg L–1 NO3–N points toward the latter. The NO3–N MCLG was established to protect against bottle-fed infant (<6 months) methemoglobinemia.7 Emerging evidence associates <MCL NO3–N concentrations with other adverse health outcomes,116 including cancer,117 thyroid disease,118 and neural tube defects.119

3.3. TW Manganese

No Mn MCL97 (or WHO GV89) currently exists, but USEPA maintains a 300 μg L–1 lifetime drinking-water health advisory (DWHA; assumes 100% exposure from drinking water).97 Approximately 32% (18/56) of the samples in this study (75% in community C) exceeded or equaled the USEPA DWHA, raising concerns about prolonged exposures. More concerning, a Mn concentration greater than the 1 day acute exposure level of 1 mg L–1 for small (≤10 kg) children97 co-occurred in a private-well TW sample with a greater than MCL-equivalent U concentration, again emphasizing the elevated risk of unrecognized exposures in private-well TW. Community B Mn concentrations differed by an order of magnitude (p = 0.0002) between surface-water-sourced public-supply (median: 2 μg L–1) and groundwater-sourced (private-/public-supply median: 23 μg L–1) samples. Median Mn concentrations were more than an order of magnitude higher in community C samples (all groundwater-sourced), with no difference (p = 0.21) between private- and public-supply locations (medians 575 and 554 μg L–1, respectively). However, the highest Mn concentration in this study (2880 μg L–1) was observed in a private-well TW sample in community C, which also had the study’s highest dissolved Fe (4640 μg L–1) and only >MCL-equivalent U concentration (34 μg L–1). As noted above, frequent co-occurrence in groundwater-sourced TW samples of redox-reactive inorganics, including those (e.g., As and U) mobilized under different redox conditions, is consistent with widespread well-water redox heterogeneity.34

Across the US, approximately 6.9% of drinking-water-aquifer samples (n = 3662) exceeded 300 μg L–1 Mn, an exceedance rate comparable to those for MCL-equivalent concentrations of NO3–N (4.1%) and As (6.7%) in the same wells.6 Groundwater Mn concentrations in excess of 300 μg L–1 were associated with proximity to surface waters and organic-rich soils,120 consistent with the elevated Mn concentrations observed in community C, near a large regional lake. Growing concerns for cognitive, neurodevelopmental, and behavioral effects of long-term exposures in children have prompted calls to re-evaluate the regulation/monitoring of drinking-water Mn.121,122 To protect against neurological effects in bottle-fed infants, WHO123 recently released a provisional Mn GV of 80 μg L–1, a value exceeded by 39% (22/56) of samples in the current study (85% of community C).

3.4. TW Selenium

Elevated drinking-water Se has been proposed as a risk factor for adverse health outcomes,124 including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson’s disease,125 neurotoxicity,126 and skin cancer.127 Elevated serum Se concentrations have been associated with diabetes and elevated fasting glucose.128,129 While the USEPA Se MCLG is currently 50 μg L–1,97,130 growing concerns prompted a recent 20 μg L–1 European Commission parametric value for Se.131 Based on a comparative cohort (exposed, unexposed) study of long-term exposure to drinking-water Se in the range of 7–10 μg L–1 in northern Italy,132,133 a drinking-water limit of 1 μg L–1 was proposed to decrease the risk of adverse health effects, including neoplasms and endocrine and neurological diseases.134 In the current study, Se was detected in excess of 1 μg L–1 in 26% (9/34) of private-well TW samples (8/14 community A), but not in any public-supply samples.

3.5. TW Fluoride

Detected F concentrations (Figure S1, Table S3) were well below the USEPA MCL established to protect against bone fragility and skeletal fluorosis,7,8 indicating little concern for this toxic effect from TW exposures within the study area. However, all F concentrations in the current study were below the US Public Health Service135 optimum of 0.7 mg L–1 to prevent dental caries (Figure S1), consistent with groundwater results6,136 and dental-health concerns for children on private-wells11 across the US. The American Academy of Pediatrics137 and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC)138 recommend F supplementation for children if their drinking water contains <0.6 mg L–1 F.

3.6. TW Organics

TW samples were screened for 4 cyanotoxins, 22 DBP, 218 pesticide, 34 PFAS, 78 VOC, and 112 pharmaceutical analytes. Among the 63 organic analytes detected at least once, 59% (38) were detected in 5% (≤3) or fewer samples, with 20 (31%) detected only once. At least one organic analyte was detected in 79% (44/56) of the TW sample locations, with more than one detected in 59% (33/56) of locations. Higher numbers and cumulative concentrations of detected organics were observed in public-supply TW samples than in private supply in communities B and C (p = 0.0001), attributable primarily to DBP. In general, few organics were detected in private-well samples (Figures 4 and 5), with 35% (12/34) having no organic detections; a median detection of 1 for communities A (range: 1–9), B (range: nd–4), and C (range: nd–6); and no systematic detections. However, the highest individual (isopropyl alcohol; Chemical Abstract Service [CAS] number: 67-63-0) and cumulative concentrations of detected organics (all VOC) were observed in a private-well TW sample from community A; isopropyl alcohol is a common household solvent and personal care product.139

Figure 5.

Cumulative concentrations (circles, ●) of all organics (plot A) and select organic classes (plots B–D) detected during 2019 in North Dakota and South Dakota in public-supply (shaded) and private-supply (unshaded) TW samples within each study area. Boxes, centerlines, and whiskers indicate interquartile range, median, and 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively. Numbers above each boxplot pair indicate the permuted probability that the centroids and dispersions are the same (PERMANOVA; 9999 permutations). “nd” indicates not detected.

The VOC class dominated organic detections and concentrations in private-supply TW, on average (median) accounting for 100% of cumulative detections (IQR: 50–100%) and concentrations (IQR: 82–100%) in samples with detectable organics. The most frequent organic analyte detections in private-well TW (24%) were generally trace levels of 1,1-difluoroethane (CAS: 75-37-6), most commonly used as an aerosol propellant;139 similar frequency (27%) sporadic detections in public-supply samples are most readily reconciled with trace residential air contamination. The co-occurrence of multiple petroleum-hydrocarbon contaminants in two remote rural, private-well TW locations is consistent with groundwater contamination from farm-related refueling activities. VOC remained a frequently detected class in public-supply TW locations, with predominantly xylenes observed in community C and xylenes and the fuel-oxygenate, t-butyl alcohol, systematically detected in community B. However, consistent with previous findings,29,30,43,44 DBP dominated public supply organics, representing on average (median) 58% of detections and 92% of cumulative concentrations. Cumulative DBP concentrations were more than an order of magnitude higher (p < 0.0001) in surface-water-sourced public-supply TW samples (community B only; median: 24.2 μg L–1) than in groundwater-sourced public-supply locations (median: 2.0 μg L–1) in communities B and C. Consistent with widespread agricultural use within Corn Belt drainage basins,140,141 including the Missouri River basin,142 pesticides (median: 6) were detected (concentrations ≤ 0.33 μg L–1) in every surface-water-sourced public-supply sample but were rarely detected in any groundwater-sourced location in this study. Other notable, albeit less frequent, organic detections of growing human-health concerns included PFAS compounds (PFBA, one private supply, 83.7 ng L–1; PFBS, two private supplies, maximum 13.2 ng L–1) and cyanotoxins (cylindrospermopsin, one public supply, 90 ng L–1; saxitoxins, two private supplies, both 30 ng L–1), all below current lowest state drinking-water ALs or advisories for PFBA (7000 ng L–1),143 PFBS (345 ng L–1),144 cylindrospermopsin (700 ng L–1),145 and saxitoxins (300 ng L–1).145

Among the 63 detected organics, 16 have MCLG; among these 12 have individual MCL and 4 are addressed as a class by the trihalomethane (THM) MCL. No MCL or MCL-equivalent concentration was exceeded in public- or private-supply samples, respectively. However, seven detected analytes have an MCLG of zero. Among these MCLG exceedances, only bromodichloromethane, tribromomethane, and dichloromethane were detected in more than one sample and only in treated public supplies. The remaining MCLG (zero) exceedances were single detections each of 1,2-dichloropropane, benzene, trichloroethene (TCE), and vinyl chloride.

3.7. TW In Vitro ER, AR, and GR Bioactivity

While estrogenic activity was detected in five samples above the T47D-KBluc minimum detectable concentration [MDC; 0.0683 ng 17β-estradiol equivalents (E2Eq) L–1], and androgenic activity was detected in one sample above the CV1-chAR MDC (0.9 ng dihydrotestosterone equiv L–1), glucocorticoid activity was not detected above its bioassay MDC (Table S8). No detected activity (estrogen or androgen activity) exceeded respective drinking water effect-based trigger values (indicative of adverse health effects) previously developed for similar molecular-endpoint bioassays.146

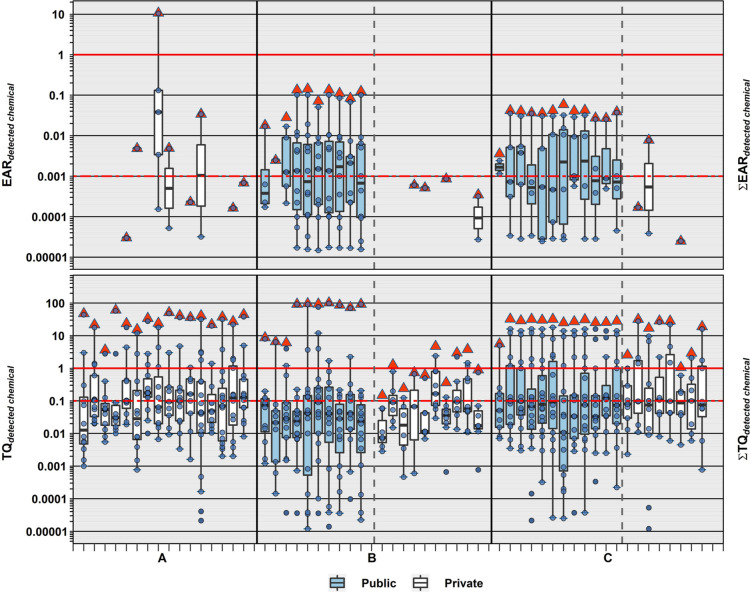

3.8. TW Aggregated Screening Assessment: ΣEAR and ΣTQ

We screened for TW cumulative-exposure effects of potential human-health interest using two analogous bioactivity-weighted approaches (ΣEAR, ΣTQ) with distinct strengths and limitations. Both are based on detected TW constituents and constrained by the analytical scope (468 organics and 33 inorganics), which, while extensive, is an orders-of-magnitude underestimate of the contaminant exposures documented in drinking-water sources. Likewise, both approaches are limited to available weighting factors (ToxCast ACC and human-health benchmarks, respectively) and assume cumulative effects are reasonably approximated by concentration addition.83,85,147 The ΣEAR approach29,48 leverages high-throughput exposure-effects data for the 10,000 + organics and approximately 1000 vertebrate-cell-line molecular endpoints148,149 in the invitroDBv3.2 release150 of the ToxCast database to estimate potential cumulative activity at sensitive and possibly more protective sublethal molecular endpoints but has limited to no coverage of inorganic contaminants and unknown transferability to organ/organism scales.151 Importantly, the approach employed here aggregates contaminant bioactivity ratios across all endpoints without restriction to recognized modes of action as a precautionary screening for further investigation of potential effects but may not accurately reflect the apical effects that typically drive regulatory risk assessments.48,151 In contrast, the ΣTQ HI approach provides insight into potential effects of simultaneous inorganic and organic exposures and is targeted at apical human-health effects, but it is notably constrained to available regulatory risk determinations.

Only about half (32) of the 63 organics detected in TW in this study and only 5 of 12 detected DBP had exact Chemical Abstract Services (CAS) number matches in the ToxCast invitroDBv3.2 database (Figure S2; Table S10). Consistent with the presence of DBP in public supply and the generally infrequent and low-concentration detections of organics in private supplies, site-specific ΣEAR was higher (p = 0.0001) in public-supply TW (median: 0.0412) than in private supply (median: <0.00001) (Figure 6; Table S10). However, the highest EAR (and ΣEAR) in this study was observed in a private-well TW sample from community A with a concentration of 1-butanol more than 10 times that (ACC) shown to modulate molecular targets in vitro (i.e., solid red ΣEAR = 1 line). Individual EAR or ΣEAR near or above 0.1 in the seven surface-water-sourced TW samples from community B indicated an elevated probability of effects, driven primarily by the DBP, chlorodibromomethane. Exceedance of ΣEAR = 0.001 (precautionary screening-level threshold of interest) in all public-supply and five private-supply samples indicated that further investigation of the cumulative biological activity from SHWS area TW exposures is warranted, even when considering only the organic contaminants detected in this study.

Figure 6.

Top. Individual EAR values (circles, ●) and cumulative EAR (ΣEAR, sum of all detected; red triangles, ▲) across all assays for 32 organic analytes listed in ToxCast and detected in public-supply (shaded) and private-supply (unshaded) TW samples collected during 2019 in North Dakota and South Dakota. Solid and dashed red lines indicate concentrations shown to modulate effects in vitro and effects-screening-level thresholds (EAR = 0.001), respectively. Bottom. Human health benchmark-based individual TQ values (circles, ●) and cumulative TQ (ΣTQ, sum of all detected; red triangles, ▲) for inorganic and organic analytes listed in Table S12 and detected in treated public-supply (shaded) and untreated private-supply (unshaded) TW samples. Solid and dashed red lines indicate benchmark equivalent concentrations and effects-screening-level threshold of concern (TQ = 0.1), respectively. Boxes, centerlines, and whiskers indicate interquartile range, median, and 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively, for both plots.

Every TW sample exceeded the ΣTQ = 0.1 HI screening threshold of concern and all, but four, private-well TW samples exceeded ΣTQ = 1 (Table S12). These ΣTQ results indicate high probabilities of aggregated risks in SHWS private- and public-supply TW samples when considering exposures to both organic and inorganic chemicals (Figures 6 and S3; Table S13). ΣTQ was driven primarily by inorganics (As, Mn, Pb, and U) in private-well TW samples and by organics (DBP) and inorganics (As, Mn, Pb, and U) in public-supply TW samples. Site-specific HI were higher (p = 0.0009) in public-supply (median: 30.6) than in private-supply (median: 20.3) TW (Figure 7), with only modest differences (p = 0.0301) in community C but approximately two orders-of-magnitude higher (p = 0.0001) median ΣTQ in community B public-supply (median: 89.6) versus private-supply (median: 0.82) samples. Common-place DBP-driven exceedance of HI screening-levels of concern in public-supply TW, in this study and previously,29,30,43,44 reemphasize the public-health tradeoff of chlorine disinfection,152,153 the importance of better understanding of the cumulative DBP health risks,152,154 and the need for improved DBP-precursor (e.g., natural organic matter) removal prior to disinfection.155,156 Likewise, frequent exceedances of the ΣTQ HI screening level of 0.1 in unregulated and generally unmonitored private-supply TW in this and previous studies29,30,44 reiterate the inherent human-health challenge of unmonitored TW.6,12,21−23 Simultaneous co-occurring inorganic and organic exposures and corresponding potentials for cumulative effects add weight to previous recommendations for systematic private-supply monitoring,23 with an analytical scope that more realistically reflects the breadth of inorganic and organic environmental contamination.5,157

Figure 7.

Cumulative EAR (ΣEAR, left, organics only) and cumulative TQ (ΣTQ, right, inorganics and organics) for analytes detected in public-supply (shaded) and private-supply (unshaded) TW samples during 2019 in North Dakota and South Dakota within each study area. Solid and dashed red lines indicate in vitro effect or benchmark equivalent exposures (ΣEAR = 1, ΣTQ = 1) and effects-screening-level thresholds of concern (ΣEAR = 0.001, ΣTQ = 0.1), respectively. Boxes, centerlines, and whiskers indicate interquartile range, median, and 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively. Numbers above each boxplot pair indicate the permuted probability that the centroids and dispersions are the same (PERMANOVA; 9999 permutations).

3.9. Implications for Drinking-Water Treatment and TW Exposure Mitigation

The results indicate effective treatment of regulated contaminant exposures to below MCL levels in all public-supply TW samples in this study. Considering the multiple exceedances of health-only MCLG,7,8 however, complete communication of public-supply TW monitoring results, including exposures below current MCL, is needed to support consumer POU-treatment decision-making. Likewise, the ongoing SHWS As intervention has documented an effective reduction of TW As exposures in private-well locations in the study area using POU adsorptive media.41 In light of growing evidence for human-health effects of exposures to currently unregulated TW contaminants (e.g., unregulated DBP154 and PFAS158) or to regulated contaminants at <MCL concentrations (e.g., As98 and NO3116), common co-occurrences of multiple analytes with human-health implications in both private- and public-supply samples, including co-occurring exceedances of MCLG and ΣTQ > 1, may reasonably raise consumer concerns1,2 and corresponding interest in POE/POU treatment.159 The median per sample number of health-benchmark exceedances in this study was two (range: 0–5), illustrating the importance of identifying stand-alone POE/POU treatment options for unregulated private-well TW, which are effective against multiple contaminants,159,160 and highlighting the potential value of POU treatment of public-supply TW for additional contaminant removal, including DBP.159

Several POE/POU treatment technologies are effective in reducing TW exposures to the contaminants identified in this study.159 The protectiveness of POE/POU approaches depends on the selection of appropriate filtration technologies for exposures of concern, timely and effective maintenance, and monitoring to confirm acceptable performance. For locations in the study area where geogenic contaminants like As and U are the only exposures of apparent concern, single-stage configurations of multiple treatment technologies are appropriate, including solid-block activated carbon, ion exchange media, redox media, and reverse osmosis (RO).159,161 However, broadly effective single-stage treatment technologies, such as RO, or multistage/multifiltration systems (sediment filter, redox media, activated carbon, ion exchange, RO, and UV disinfection) may be more appropriate for those locations with mixtures of inorganic and organic contaminants or unknown contaminant-exposure profiles (i.e., unmonitored private wells).159

4. Conclusions

Assessment and communication of TW contaminant exposures are essential to contaminant-risk-management and public-health decision-making at household and community scales. The perceived risks of and resultant resource commitments to drinking-water contaminant exposures are highly variable at both scales due to differences in availability of actionable drinking-water contaminant exposure/risk information, risk acceptability/tolerance thresholds, and overall exposure/risk portfolios (exposome).153,162 In the US, SDWA-stipulated annual public-supply consumer confidence reports support community and household-level decision-making, but decisions concerning additional community- or household-level treatment of public-supply TW are constrained by limited information on unregulated contaminants and on <MCL (or <AL) concentrations of regulated contaminants. Limited financial resources, water-quality expertise, and contaminant exposure data at the household scale fundamentally constrain private-supply decision-making and risk-mitigation options.23,29,44 Analytically extensive datasets like this study, which are intended to inform scientific and public-health understanding of the role of drinking water as a vector for human contaminant exposures and associated human-health outcomes, remain limited because broad assessment of regulated and unregulated contaminants are not generally conducted at the TW point of exposure in the US or worldwide.

These results indicate that simultaneous exposures to contaminants of human-health interest are common in both public- and private-supply TW locations across the study area. The bioactivity-weighted screening (ΣEAR and ΣTQ) results (Tables S10 and S13) indicate that exposures to DBP and inorganics at <MCL concentrations are the primary drivers of human-health interest in public-supply TW in communities B and C. These public-supply results align with the previous findings29,30,43,44 and support the need for better understanding of exposure-effect relations and cumulative health risks of regulated/unregulated DBP152,154 and for improved source-water pretreatment technologies to address DBP precursors, such as surface-water natural organic matter.156,163 Exposures to As and U in groundwater-sourced drinking-water supplies have been reported previously in the study area and the concentrations observed in public-supply TW herein were below corresponding NPDWR MCL. However, because there is no known safe level of exposure for either compound (i.e., MCLG zero), community and individual interests in improved drinking-water facility processes and household treatment options are reasonable. The benchmark-weighted screening (ΣTQ) results (Table S13) also indicate that exposures to inorganics often at concentrations above NPDWR MCL-equivalent concentrations are frequent drivers of potential human-health concerns for private-supply TW across the study area, along with more sporadic detections of Pb and other anthropogenic contaminants.

Thus, these results substantiate continued expansion and connection of public-supply systems to limit contaminant exposures to <MCL concentrations and incorporation of well-maintained POE/POU treatment as an integral complementary line of consumer protection for public-supply TW during normal and outbreak conditions29,161,164 and as prudent protection against unrecognized simultaneous exposures to multiple contaminants in private-supply homes.29,41 These results emphasize the importance of continued characterization of POU TW exposures, especially in unregulated and unmonitored private supplies and small community water supplies, using an analytical coverage that serves as a realistic indicator of the breadth and complexity of inorganic and organic contaminant mixtures known to occur in ambient source waters5,157 to support models of TW contaminant exposures and related risks. Increased availability of such health-based monitoring data, including results below current, technically/economically constrained enforceable standards (e.g., MCL), is important to support public engagement in source-water protection and drinking-water treatment and to inform consumer POE/POU treatment decisions in these Tribal communities and throughout the US.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Strong Heart Water Study participants and participating Tribal Nations for their support of this drinking-water research. We thank Jacqueline Bangma (USEPA), Brian Tornabene (USGS), and three anonymous journal referees for their reviews. This research was conducted and funded by the USGS Ecosystems Mission Area, Environmental Health Program. The Strong Heart Water Study team was supported by 1R01ES025135. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The findings and conclusions in this article do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the US Environmental Protection Agency, NIH/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Indian Health Service, or Bureau of Indian Affairs. This report contains CAS Registry Numbers, which is a registered trademark of the American Chemical Society. CAS recommends the verification of the CASRNs through CAS Client ServicesSM.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsestwater.2c00293.

Site information; compound information for analyses performed by various laboratories for the USGS; parameters and concentrations of analyzed major anions and cations; detected organic compounds; inorganic analyte detections; concentrations of the analytes detected in organic analyte quality assurance field blanks; surrogate recovery or internal dilution standard summary statistics; mammalian bioactivities; endpoint combinations excluded from ToxCast evaluation; site-specific EAR; and human-health-based benchmarks; and site-specific TQ (XLSX)

Analytical methods, risk assessment, acknowledgments, and references (PDF)

Author Contributions

CRediT: Paul M. Bradley conceptualization (lead), data curation (lead), formal analysis (lead), investigation (lead), methodology (lead), project administration (lead), visualization (supporting), writing-original draft (lead), writing-review & editing (lead); Kristin M. Romanok conceptualization (supporting), data curation (lead), formal analysis (equal), investigation (equal), visualization (lead), writing-review & editing (equal); Kelly L. Smalling conceptualization (supporting), formal analysis (equal), investigation (equal), writing-review & editing (equal); Michael J. Focazio conceptualization (supporting), investigation (supporting), writing-review & editing (supporting); Robert Charboneau investigation (supporting), resources (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); Christine Marie George conceptualization (supporting), investigation (supporting), resources (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); Ana Navas-Acien conceptualization (supporting), investigation (supporting), resources (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); Marcia O’Leary conceptualization (supporting), investigation (supporting), resources (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); Reno Red Cloud conceptualization (supporting), investigation (supporting), resources (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); Tracy Zacher conceptualization (supporting), investigation (supporting), resources (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); Sara E. Breitmeyer visualization (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); Mary C. Cardon formal analysis (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); Christa K. Cuny investigation (supporting), writing-review & editing (supporting); Guthrie Ducheneaux investigation (supporting), writing-review & editing (supporting); Kendra Enright investigation (supporting), writing-review & editing (supporting); Nicola Evans formal analysis (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); James L. Gray formal analysis (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); David E. Harvey investigation (supporting), writing-review & editing (supporting); Michelle L. Hladik formal analysis (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); Leslie K. Kanagy formal analysis (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); Keith A. Loftin formal analysis (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); R. Blaine McCleskey formal analysis (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); Elizabeth K. Medlock-Kakaley formal analysis (equal), writing-review & editing (supporting); Shannon M. Meppelink formal analysis (equal), investigation (supporting), writing-review & editing (supporting); Joshua F. Valder investigation (supporting), writing-review & editing (supporting); Christopher Weis investigation (supporting), writing-review & editing (supporting).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Pierce G.; Gonzalez S. Mistrust at the tap? Factors contributing to public drinking water (mis) perception across US households. Water Pol. 2017, 19, 1–12. 10.2166/wp.2016.143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doria M.d. F. Factors influencing public perception of drinking water quality. Water Pol. 2010, 12, 1–19. 10.2166/wp.2009.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva C. M.; Kogevinas M.; Cordier S.; Templeton M. R.; Vermeulen R.; Nuckols J. R.; Nieuwenhuijsen M. J.; Levallois P. Assessing exposure and health consequences of chemicals in drinking water: current state of knowledge and research needs. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 213. 10.1289/ehp.1206229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Walker G. W.; Muir D. C. G.; Nagatani-Yoshida K. Toward a global understanding of chemical pollution: a first comprehensive analysis of national and regional chemical inventories. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 2575. 10.1021/acs.est.9b06379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley P. M.; Journey C.; Romanok K.; Barber L.; Buxton H. T.; Foreman W. T.; Furlong E. T.; Glassmeyer S.; Hladik M.; Iwanowicz L. R.; Jones D.; Kolpin D.; Kuivila K.; Loftin K.; Mills M.; Meyer M.; Orlando J.; Reilly T.; Smalling K.; Villeneuve D. Expanded Target-Chemical Analysis Reveals Extensive Mixed-Organic-Contaminant Exposure in U.S. Streams. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 4792–4802. 10.1021/acs.est.7b00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSimone L. A.; McMahon P. B.; Rosen M. R.. The quality of our Nation’s waters: water quality in Principal Aquifers of the United States, 1991-2010; USGS: Reston, VA, 2015; Vol. 1360, p 161.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency . National Primary Drinking Water Regulations, 2021. https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/national-primary-drinking-water-regulations (July 11, 2021).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency . 141: National Primary Drinking Water Regulations; U.S. Environmmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, 2021. 40 C.F.R.. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=1&SID=339dba02478821f8412c44292656bd34&ty=HTML&h=L&mc=true&n=pt40.25.141&r=PART#_top.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration . Bottled water: Washington, DC, 2021; 21 C.F.R. § 165.110In 21 C.F.R.. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-165/subpart-B/section-165.110#page-top.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Private drinking water wells, 2021. https://www.epa.gov/privatewells (March 30, 2021).

- Committee on Environmental Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases Drinking water from private wells and risks to children. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1599–1605. American Academy of Pediatrics 10.1542/peds.2009-0751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogan W. J.; Brady M. T. Drinking water from private wells and risks to children. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e1123–e1137. 10.1542/peds.2009-0752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y. Lessons Learned from Arsenic Mitigation among Private Well Households. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 373–382. 10.1007/s40572-017-0157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wescoat J. L.; Headington L.; Theobald R. Water and poverty in the United States. Geoforum 2007, 38, 801–814. 10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nigra A. E. Environmental racism and the need for private well protections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 17476–17478. 10.1073/pnas.2011547117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayotte J. D.; Medalie L.; Qi S. L.; Backer L. C.; Nolan B. T. Estimating the high-arsenic domestic-well population in the conterminous United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 12443–12454. 10.1021/acs.est.7b02881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard M. A.; Scannell Bryan M.; Jones D. K.; Bulka C.; Bradley P.; Backer L.; Focazio M.; Silverman D.; Toccalino P.; Argos M.; Gribble M.; Ayotte J. D. Machine learning models of arsenic in private wells throughout the conterminous United States as a tool for exposure assessment in human health studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 5012. 10.1021/acs.est.0c05239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayotte J. D.; Belaval M.; Olson S. A.; Burow K. R.; Flanagan S. M.; Hinkle S. R.; Lindsey B. D. Factors affecting temporal variability of arsenic in groundwater used for drinking water supply in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 505, 1370–1379. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard M. A.; Daniel J.; Jeddy Z.; Hay L. E.; Ayotte J. D. Assessing the impact of drought on arsenic exposure from private domestic wells in the conterminous United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 1822–1831. 10.1021/acs.est.9b05835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma J.; Butterfield P. W.; Odom-Maryon T.; Hill W.; Butterfield P. G. Rural children’s exposure to well water contaminants: Implications in light of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recent policy statement. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2011, 23, 258–265. 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2011.00609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focazio M. J.; Tipton D.; Dunkle Shapiro S. S.; Geiger L. H. The chemical quality of self-supplied domestic well water in the United States. Ground Water Monit. Remed. 2006, 26, 92–104. 10.1111/j.1745-6592.2006.00089.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald Gibson J.; Pieper K. Strategies to improve private-well water quality: A North Carolina perspective. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 076001. 10.1289/ehp890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y.; Flanagan S. V. The case for universal screening of private well water quality in the U.S. and testing requirements to achieve it: Evidence from arsenic. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 085002. 10.1289/ehp629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane K.; Harris L. M. Small systems, big challenges: Review of small drinking water system governance. Environ. Rev. 2018, 26, 378–395. 10.1139/er-2018-0033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balazs C. L.; Ray I. The drinking water disparities framework: On the origins and persistence of inequities in exposure. Am. J. Publ. Health 2014, 104, 603–611. 10.2105/ajph.2013.301664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanDerslice J. Drinking Water Infrastructure and Environmental Disparities: Evidence and Methodological Considerations. Am. J. Publ. Health 2011, 101, S109–S114. 10.2105/ajph.2011.300189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allaire M.; Wu H.; Lall U. National trends in drinking water quality violations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018, 115, 2078–2083. 10.1073/pnas.1719805115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan S. V.; Zheng Y. Comparative case study of legislative attempts to require private well testing in New Jersey and Maine. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2018, 85, 40–46. 10.1016/j.envsci.2018.03.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley P. M.; LeBlanc D. R.; Romanok K. M.; Smalling K. L.; Focazio M. J.; Cardon M. C.; Clark J. M.; Conley J. M.; Evans N.; Givens C. E.; Gray J. L.; Earl Gray L.; Hartig P. C.; Higgins C. P.; Hladik M. L.; Iwanowicz L. R.; Loftin K. A.; Blaine McCleskey R.; McDonough C. A.; Medlock-Kakaley E. K.; Weis C. P.; Wilson V. S. Public and private tapwater: Comparative analysis of contaminant exposure and potential risk, Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA. Environ. Int. 2021, 152, 106487. 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley P. M.; Kolpin D. W.; Romanok K. M.; Smalling K. L.; Focazio M. J.; Brown J. B.; Cardon M. C.; Carpenter K. D.; Corsi S. R.; DeCicco L. A.; Dietze J. E.; Evans N.; Furlong E. T.; Givens C. E.; Gray J. L.; Griffin D. W.; Higgins C. P.; Hladik M. L.; Iwanowicz L. R.; Journey C. A.; Kuivila K. M.; Masoner J. R.; McDonough C. A.; Meyer M. T.; Orlando J. L.; Strynar M. J.; Weis C. P.; Wilson V. S. Reconnaissance of mixed organic and inorganic chemicals in private and public supply tapwaters at selected residential and workplace sites in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 13972. 10.1021/acs.est.8b04622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox M. A.; Nachman K. E.; Anderson B.; Lam J.; Resnick B. Meeting the public health challenge of protecting private wells: Proceedings and recommendations from an expert panel workshop. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 554-555, 113–118. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.02.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong Heart Study Strong Heart Study: The Largest Epidemiological Study of Cardiovascular Disease in American Indians; University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, 2021, https://strongheartstudy.org/.

- Focazio M. J.; Welch A. H.; Watkins S. A.; Helsel D. R.; Horn M. A.. A Retrospective Analysis on the Occurrence of Arsenic in Ground-Water Resources of the United States and Limitations in Drinking-Water-Supply Characterizations; USGS, 2000; pp 99–4279.

- Sobel M.; Sanchez T. R.; Zacher T.; Mailloux B.; Powers M.; Yracheta J.; Harvey D.; Best L. G.; Bear A. B.; Hasan K.; Thomas E.; Morgan C.; Aurand D.; Ristau S.; Olmedo P.; Chen R.; Rule A.; O’Leary M.; Navas-Acien A.; George C. M.; Bostick B. Spatial relationship between well water arsenic and uranium in Northern Plains native lands. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117655. 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Esquinas E.; Pollán M.; Umans J. G.; Francesconi K. A.; Goessler W.; Guallar E.; Howard B.; Farley J.; Best L. G.; Navas–Acien A. Arsenic exposure and cancer mortality in a US-based prospective cohort: The Strong Heart Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2013, 22, 1944–1953. htpps: 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-13-0234-t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon K.; Guallar E.; Umans J.; Devereux R.; Best L.; Francesconi K. A.; Goessler W.; Pollack J. R.; Silbergeld Ellen K.; Howard B.; Navas-Acien A. Association between exposure to low to moderate arsenic levels and incident cardiovascular disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 159, 649–659. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L. Y.; Umans J. G.; Yeh F.; Francesconi K. A.; Goessler W.; Silbergeld E. K.; Bandeen-Roche K.; Guallar E.; Howard B. V.; Weaver V. M.; Navas-Acien A. The Association of Urine Arsenic with Prevalent and Incident Chronic Kidney Disease. Epidemiology 2015, 26, 601–612. 10.1097/ede.0000000000000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers M.; Sanchez T. R.; Grau-Perez M.; Yeh F.; Francesconi K. A.; Goessler W.; George C. M.; Heaney C.; Best L. G.; Umans J. G.; Brown R. H.; Navas-Acien A. Low-moderate arsenic exposure and respiratory in American Indian communities in the Strong Heart Study. Environ. Health 2019, 18, 104. 10.1186/s12940-019-0539-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinkelman N. E.; Spratlen M. J.; Domingo-Relloso A.; Tellez-Plaza M.; Grau-Perez M.; Francesconi K. A.; Goessler W.; Howard B. V.; MacCluer J.; North K. E.; Umans J. G.; Factor-Litvak P.; Cole S. A.; Navas-Acien A. Associations of maternal arsenic exposure with adult fasting glucose and insulin resistance in the Strong Heart Study and Strong Heart Family Study. Environ. Int. 2020, 137, 105531. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau-Perez M.; Kuo C.-C.; Gribble M. O.; Balakrishnan P.; Jones Spratlen M. J.; Vaidya D.; Francesconi K. A.; Goessler W.; Guallar E.; Silbergeld E. K.; Umans J. G.; Best L. G.; Lee E. T.; Howard B. V.; Cole S. A.; Navas-Acien A. Association of low-moderate arsenic exposure and arsenic metabolism with incident diabetes and insulin resistance in the Strong Heart Family Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 127004. 10.1289/ehp2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers M.; Yracheta J.; Harvey D.; O’Leary M.; Best L. G.; Black Bear A.; MacDonald L.; Susan J.; Hasan K.; Thomas E.; Morgan C.; Olmedo P.; Chen R.; Rule A.; Schwab K.; Navas-Acien A.; George C. M. Arsenic in groundwater in private wells in rural North Dakota and South Dakota: Water quality assessment for an intervention trial. Environ. Res. 2019, 168, 41–47. 10.1016/j.envres.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas E. D.; Gittelsohn J.; Yracheta J.; Powers M.; O’Leary M.; Harvey D. E.; Red Cloud R.; Best L. G.; Black Bear A.; Navas-Acien A.; George C. M. The Strong Heart Water Study: Informing and designing a multi-level intervention to reduce arsenic exposure among private well users in Great Plains Indian Nations. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 3120–3133. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley P. M.; Argos M.; Kolpin D. W.; Meppelink S. M.; Romanok K. M.; Smalling K. L.; Focazio M. J.; Allen J. M.; Dietze J. E.; Devito M. J.; Donovan A. R.; Evans N.; Givens C. E.; Gray J. L.; Higgins C. P.; Hladik M. L.; Iwanowicz L. R.; Journey C. A.; Lane R. F.; Laughrey Z. R.; Loftin K. A.; McCleskey R. B.; McDonough C. A.; Medlock-Kakaley E.; Meyer M. T.; Putz A. R.; Richardson S. D.; Stark A. E.; Weis C. P.; Wilson V. S.; Zehraoui A. Mixed organic and inorganic tapwater exposures and potential effects in greater Chicago area, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 719, 137236. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley P. M.; Padilla I. Y.; Romanok K. M.; Smalling K. L.; Focazio M. J.; Breitmeyer S. E.; Cardon M. C.; Conley J. M.; Evans N.; Givens C. E.; Gray J. L.; Gray L.; Hartig P. C.; Higgins C. P.; Hladik M. L.; Iwanowicz L. R.; Lane R. F.; Loftin K. A.; McCleskey R.; McDonough C. A.; Medlock-Kakaley E.; Meppelink S.; Weis C. P.; Wilson V. S. Pilot-scale expanded assessment of inorganic and organic tapwater exposures and predicted effects in Puerto Rico, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 788, 147721. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretto A.; Bachman A.; Boobis A.; Solomon K. R.; Pastoor T. P.; Wilks M. F.; Embry M. R. A framework for cumulative risk assessment in the 21st century. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2017, 47, 85–97. 10.1080/10408444.2016.1211618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton S. B.; Rodier D. J.; van der Schalie W. H.; Wood W. P.; Slimak M. W.; Gentile J. H. A framework for ecological risk assessment at the EPA. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1992, 11, 1663–1672. 10.1002/etc.5620111202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council . Risk Assessment in the Federal Government: Managing the Process; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 1983; p 191. [PubMed]

- Blackwell B. R.; Ankley G. T.; Corsi S. R.; DeCicco L. A.; Judson K. A.; Li R. S.; Martin S.; Murphy M. T.; Schroeder E.; Smith A.; Swintek J.; Villeneuve D. L. An″ EAR″ on environmental surveillance and monitoring: A case study on the use of exposure-activity ratios (EARs) to prioritize sites, chemicals, and bioactivities of concern in Great Lakes waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 8713–8724. 10.1021/acs.est.7b01613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency . EPA’s National-Scale Air Toxics Assessment, an Overview of Methods for EPA’s National-Scale Air Toxics Assessment, 2011. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-10/documents/2005-nata-tmd.pdf.

- Goumenou M.; Tsatsakis A. Proposing new approaches for the risk characterisation of single chemicals and chemical mixtures: The source related Hazard Quotient (HQS) and Hazard Index (HIS) and the adversity specific Hazard Index (HIA). Toxicol. Rep. 2019, 6, 632–636. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2019.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi S. R.; De Cicco L. A.; Blackwell D. L.; Fay B. R.; Ankley K. A.; Baldwin G. T.; Baldwin A. K. Prioritizing chemicals of ecological concern in Great Lakes tributaries using high-throughput screening data and adverse outcome pathways. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 686, 995–1009. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency . Lead and Copper Rule: A Quick Reference Guide, 2008, (March 3, 2022).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency . National Primary Drinking Water Regulations: Lead and Copper Rule Revisions - Pre-publication Version; U.S. Environmmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, 2020; 40 C.F.R. § 141 and § 14240 C.F.R. § 141/142.

- Romanok K. M.; Kolpin D. W.; Meppelink S. M.; Argos M.; Brown J.; DeVito M.; Dietz J. E.; Gray J.; Higgins C. P.; Hladik M. L.; Iwanowicz L. R.; McCleskey B. R.; McDonough C.; Meyers M. T.; Strynar M.; Weis C. P.; Wilson V.; Bradley P. M.. Methods Used for the Collection and Analysis of Chemical and Biological Data for the Tapwater Exposure Study, United States, 2016–17; U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2018-1098: Reston, VA, 2018; p 81.

- Romanok K. M.; Bradley P. M.. Target-Chemical Concentration Results for Assessment of Mixed-Organic/Inorganic Chemical and Biological Exposures in North Dakota and South Dakota Tapwater; U.S. Geological Survey data release, 2019.

- Romanok K. M.; Bradley P. M.; McCleskey R. B.. Inorganic Concentration Results for Assessment of Mixed-Organic/Inorganic Chemical and Biological Exposures in North Dakota and South Dakota Tapwater; U.S. Geological Survey data release, 2021.

- Rose D.; Sandstrom M.; Murtagh L.. Methods of the National Water Quality Laboratory. Chapter B12. Determination of heat purgeable and ambient purgeable volatile organic compounds in water by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods. Book 5. Laboratory Analysis, 2016; p 61.

- Sandstrom M. W.; Kanagy L. K.; Anderson C. A.; Kanagy C. J.. Methods of the National Water Quality Laboratory. Chapter B11. Determination of pesticides and pesticide degradates in filtered water by direct aqueous-injection liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods. Book 5. Laboratory Analysis, 2015; p 73.

- Hladik M. L.; Focazio M. J.; Engle M. Discharges of produced waters from oil and gas extraction via wastewater treatment plants are sources of disinfection by-products to receiving streams. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 466-467, 1085–1093. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong E.; Noriega M.; Kanagy C.; Kanagy L.; Coffey L.; Burkhardt M.. Methods of the National Water Quality Laboratory. Chapter B10. Determination of human-use pharmaceuticals in filtered water by direct aqueous injection–high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods. Book 5. Laboratory Analysis, 2014; Chapter B10, p 49..

- Fishman M. J.; Friedman L. C.. Methods for determination of inorganic substances in water and fluvial sediments. U.S. Geological Survey Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations 05-A1, 1989; p 545.

- Hoffman G. L.; Fishman M. J.; Garbarino J. R.. Methods of Analysis by the US Geological Survey National Water Quality Laboratory: In-bottle Acid Digestion of Whole-water Samples. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 96-225; US Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey, 1996; p 34.

- Graham J. L.; Loftin K. A.; Meyer M. T.; Ziegler A. C. Cyanotoxin mixtures and taste-and-odor compounds in cyanobacterial blooms from the Midwestern United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 7361–7368. 10.1021/es1008938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftin K. A.; Graham J. L.; Hilborn E. D.; Lehmann S. C.; Meyer M. T.; Dietze J. E.; Griffith C. B. Cyanotoxins in inland lakes of the United States: Occurrence and potential recreational health risks in the EPA National Lakes Assessment 2007. Harmful Algae 2016, 56, 77–90. 10.1016/j.hal.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff J. D.Method 300.0, Determination of Inorganic Anions by Ion Chromatography; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1993; p 30. Revision 2.1; USEPA Method 300.0.

- Ball J. W.; McCleskey R. B. A new cation-exchange method for accurate field speciation of hexavalent chromium. Talanta 2003, 61, 305–313. 10.1016/s0039-9140(03)00282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergenreder R. L.Trace Metals in Waters by GFAAS. In Accordance with U.S. EPA and Health Canada Requirements; PerkinElmer, Inc.: Waltham, MA, 2011; p 5. https://www.perkinelmer.com/lab-solutions/resources/docs/PinAAcleTraceMetalsinWaterbyGFAAAppNote.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency . Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometry, 2014; p 35. Method 6010D; EPA SW-846 Update V, accessed November 2, 2017. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-12/documents/6010d.pdf.

- Wilson V. S.; Bobseine K.; Gray L. E. Development and characterization of a cell line that stably expresses an estrogen-responsive luciferase reporter for the detection of estrogen receptor agonist and antagonists. Toxicol. Sci. 2004, 81, 69–77. 10.1093/toxsci/kfh180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson V. S.; Bobseine K.; Lambright C. R.; Gray L. E. Jr. A novel cell line, MDA-kb2, that stably expresses an androgen- and glucocorticoid-responsive reporter for the detection of hormone receptor agonists and antagonists. Toxicol. Sci. 2002, 66, 69–81. 10.1093/toxsci/66.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig P. C.; Bobseine K. L.; Britt B. H.; Cardon M. C.; Lambright C. R.; Wilson V. S.; Gray L. E. Jr. Development of two androgen receptor assays using adenoviral transduction of MMTV-Luc reporter and/or hAR for endocrine screening. Toxicol. Sci. 2002, 66, 82–90. 10.1093/toxsci/66.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig P. C.; Cardon M. C.; Lambright C. R.; Bobseine K. L.; Gray L. E.; Wilson V. S. Substitution of synthetic chimpanzee androgen receptor for human androgen receptor in competitive binding and transcriptional activation assays for EDC screening. Toxicol. Lett. 2007, 174, 89–97. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley J.; Evans N.; Cardon M.; Rosenblum L.; Iwanowicz L.; Hartig P.; Schenck K.; Bradley P.; Wilson V. Occurrence and in vitro bioactivity of estrogen, androgen, and glucocorticoid compounds in a nationwide screen of United States stream waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 4781–4791. 10.1021/acs.est.6b06515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolpin D. W.; Hubbard L. E.; Cwiertny D. M.; Meppelink S. M.; Thompson D. A.; Gray J. L. A comprehensive statewide spatiotemporal stream assessment of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in an agricultural region of the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 981–988. 10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00750. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Childress C.; Foreman W.; Conner B.; Maloney T.. New reporting procedures based on long-term method detection levels and some considerations for interpretations of water-quality data provided by the U.S. Geological Survey National Water Quality Laboratory. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 99–193, 1999; p 19.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency . Guidelines Establishing Test Procedures for the Analysis of Pollutants; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, 2020; pp 319–322. 40 C.F.R. § 136In 40 C.F.R. § 136. http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=3c78b6c8952e5e79268e429ed98bad84&mc=true&node=pt40.23.136&rgn=div5.

- Mueller D. K.; Schertz T. L.; Martin J. D.; Sandstrom M. W.. Design, analysis, and interpretation of field quality-control data for water-sampling projects. U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods Book 4, 2015; Chapter C4, p 54. 10.3133/tm4c4 [DOI]

- Foreman W. T.; Williams T. L.; Furlong E. T.; Hemmerle D. M.; Stetson S. J.; Jha V. K.; Noriega M. C.; Decess J. A.; Reed-Parker C.; Sandstrom M. W. Comparison of detection limits estimated using single- and multi-concentration spike-based and blank-based procedures. Talanta 2021, 228, 122139. 10.1016/j.talanta.2021.122139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer Ø.; Harper D. A.; Ryan P. D. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency . Sustainable Futures/Pollution Prevention (P2) Framework Manual; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, D.C., 2012; p 326. EPA-748-B12-001. https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-futures/sustainable-futures-p2-framework-manual.

- De Cicco L.; Corsi S. R.; Villeneuve D.; Blackwell B. R.; Ankley G. T.. toxEval: Evaluation of Measured Concentration Data Using the ToxCast High-Throughput Screening Database or a User-Defined Set of Concentration Benchmarks. R package version 1.0.0, 2018, (May 1, 2018)

- R Development Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna Austria, 2019. Version 3.5.2.

- Cedergreen N.; Christensen A. M.; Kamper A.; Kudsk P.; Mathiassen S. K.; Streibig J. C.; Sørensen H. A review of independent action compared to concentration addition as reference models for mixtures of compounds with different molecular target sites. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008, 27, 1621–1632. 10.1897/07-474.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altenburger R.; Scholze M.; Busch W.; Escher B. I.; Jakobs G.; Krauss M.; Krüger J.; Neale P. A.; Ait-Aissa S.; Almeida A. C.; Seiler T.-B.; Brion F.; Hilscherová K.; Hollert H.; Novák J.; Schlichting R.; Serra H.; Shao Y.; Tindall A.; Tollefsen K. E.; Umbuzeiro G.; Williams T. D.; Kortenkamp A. Mixture effects in samples of multiple contaminants - An inter-laboratory study with manifold bioassays. Environ. Int. 2018, 114, 95–106. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalter D.; O’Malley E.; von Gunten U.; Escher B. I. Mixture effects of drinking water disinfection by-products: implications for risk assessment. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 2020, 6, 2341. 10.1039/c9ew00988d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency . EPA’s National Center for Computational Toxicology: ToxCast Database (invitroDB) Vers. 5.0, 2020, accessed at https://doi.org/10.23645/epacomptox.6062623.v5.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency . ToxCast & Tox21 Summary Files from Invitrodb_v3, 2019, accessed at https://www.epa.gov/chemical-research/toxicity-forecaster-toxcasttm-data.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency . Water Quality Standards; U.S. Environmmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, 2017; 40 C.F.R. § 131In 40 C.F.R. § 131.

- World Health Organization (WHO) . Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 2011; p 631. Fourth edition incorporating the first addendum. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1080656/retrieve. [PubMed]

- Norman J. E.; Toccalino P. L.; Morman S. A.. Health-Based Screening Levels for Evaluating Water-Quality Data, 2nd ed.; U.S. Geological Survey, 2018, (February 10, 2020)

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency . How EPA Regulates Drinking Water Contaminants, 2021; https://www.epa.gov/dwregdev/how-epa-regulates-drinking-water-contaminants (July 11, 2021).

- Lanphear B.; Lowry J.; Ahdoot S.; Baum C.; Bernstein A.; Bole A.; Brumberg H.; Campbell C.; Pacheco S.; Spanier A.; Trasande L.; Osterhoudt K.; Paulson J.; Sandel M.; Rogers P. Prevention of Childhood Lead Toxicity. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161493 10.1542/peds.2016-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift Bird K.; Navarre-Sitchler A.; Singha K. Hydrogeological controls of arsenic and uranium dissolution into groundwater of the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota. Appl. Geochem. 2020, 114, 104522. 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2020.104522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S. A.; Pennino M. J.; Compton J. E.; Leibowitz S. G.; Kile M. L. Arsenic drinking water violations decreased across the United States following revision of the maximum contaminant level. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 11478–11485. 10.1021/acs.est.9b02358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigra A. E.; Sanchez T. R.; Nachman K. E.; Harvey D. E.; Chillrud S. N.; Graziano J. H.; Navas-Acien A. The effect of the Environmental Protection Agency maximum contaminant level on arsenic exposure in the USA from 2003 to 2014: an analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e513–e521. 10.1016/s2468-2667(17)30195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch B.; Smit E.; Cardenas A.; Hystad P.; Kile M. L. Trends in urinary arsenic among the U.S. population by drinking water source: Results from the National Health and Nutritional Examinations Survey 2003–2014. Environ. Res. 2018, 162, 8–17. 10.1016/j.envres.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]