Abstract

Chlamydia pneumoniae is a widely spread agent of respiratory tract infections in humans. A reliable serodiagnosis of the disease is hampered by the poor knowledge about immunodominant antigens in C. pneumoniae infections. We applied a novel strategy to identify immunogenic proteins of C. pneumoniae TW183 combining metabolic radiolabeling of de novo-synthesized chlamydial antigens with immunoprecipitation. By this technique C. pneumoniae antigens of approximately 160, 97 to 99, 60 to 62, 40, 27, and 15 kDa were detected in the vast majority of sera from patients with a current C. pneumoniae infection. By immunoblotting purified elementary bodies of C. pneumoniae TW183 with the same sera, only the 60- to 62-kDa antigen could be detected consistently. Sequential immunoprecipitation performed at different stages of the chlamydial developmental cycle revealed that the 60- to 62-kDa antigen is strongly upregulated after 24 to 48 h of host cell infection and is presented as a major immunogen in both C. pneumoniae-infected patients and mice. We conclude that, due to its high sensitivity and concurrent preservation of conformational epitopes, metabolic radiolabeling of chlamydial antigens combined with immunoprecipitation may be a useful method to reveal important immunogens in respiratory C. pneumoniae infection which might have been missed by immunoblot analysis.

Chlamydia pneumoniae, an obligate intracellular human pathogen, causes infections of the respiratory tract such as sinusitis, pharyngitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia (15, 22, 25). Seroepidemiological studies showing antibody prevalence rates in a range of 50 to 70% suggest that C. pneumoniae is widely distributed and that nearly everybody is infected with the agent at some time (25, 38). C. pneumoniae is currently of considerable interest because of its link to atherosclerosis, although it still remains unclear whether the organism plays a role as an etiological agent or only as a bystander (20, 24, 39, 45).

Laboratory diagnosis of C. pneumoniae infection is frequently based on serology because (i) cultivation of these fastidious organisms is not routinely possible and (ii) detection of C. pneumoniae DNA is not well standardized and sufficiently evaluated, compared to DNA detection for the urogenital pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis (1). Although the reactive antigen is still unknown, the microimmunofluorescence (MIF) test is widely accepted as the “gold standard” in C. pneumoniae serodiagnosis. However, concern has been raised about its sensitivity and specificity (14, 18, 26). In addition, performance of the MIF assay is time-consuming, and interpretation of the results depends significantly on the investigator’s experience. Therefore, an assay based on defined antigens could be an important improvement in C. pneumoniae serodiagnosis.

Unfortunately, there is only poor knowledge about immunogenic C. pneumoniae proteins, which are recognized consistently by sera of infected individuals. Especially the immunogenic role of the 40-kDa major outer membrane protein (MOMP) has been discussed controversially. According to some immunoblot studies, the MOMP is believed to be weakly immunogenic (2, 7, 26), while in other papers the MOMP was characterized as an immunodominant protein (19, 21). The 60-kDa cysteine-rich outer membrane protein 2 (OMP2), a structural protein of the chlamydial outer membrane complex (OMC), contains genus-reactive epitopes and seems to be a major immunogen in both human C. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis infections although it is probably not surface exposed (32, 34, 43). An artificial glycoconjugate antigen has been used to develop an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay measuring antibodies against the chlamydial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which has been characterized as a major surface antigen of chlamydial organisms (4, 5, 27). Further antigens with molecular masses of 98, 68, 60, 53, 43, 35, and 30 kDa (8, 12, 19, 21) were detected by Western blot studies, but reactivities differed significantly. In a recent immunoblot study no specific band pattern in terms of reactivity to various C. pneumoniae proteins could be determined (26). In this paper we focused on the C. pneumoniae prototype strain TW 183 and selected a panel of sera from patients with both culture- or PCR-proven respiratory C. pneumoniae infection and serological evidence for C. pneumoniae infection according to recommended criteria (25). A novel approach was applied to determine immunodominant antigens in human C. pneumoniae infection. Metabolic labeling of de novo-synthesized antigens from different chlamydial developmental stages was combined with immunoprecipitation, a method which enables sensitive detection of reactive antigens without affecting their conformational epitopes. Based on the band patterns of precipitated antigens visualized by autoradiography, we propose a profile of C. pneumoniae antigens which are consistently recognized by sera from C. pneumoniae-infected individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain.

C. pneumoniae TW 183 (Washington Research Foundation, Seattle, Wash.) was used throughout the study and maintained continuously on cycloheximide-treated HeLa 229 cell monolayers (American Type Culture Collection; CCL 2.1) in six-well culture plates by standard procedures. Glass coverslips placed into the culture plates were stained by the fluorescent-antibody technique with a Chlamydia genus-specific mouse monoclonal antibody (Pathfinder, Chaska, Minn.) to determine the percentage of infected host cells by counting the inclusion-forming units (IFU) under a fluorescence microscope. For immunoblot analysis chlamydial elementary bodies were purified by urografin density gradient centrifugation as described previously (6). For radiolabeling and immunoprecipitation, cultures with at least 80% infected host cells were harvested after 72 h and homogenized with glass beads. After brief centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C and 1,600 × g to remove cellular debris, the supernatant obtained was used for cell infection. Prior to each experiment, titers of IFU were controlled as described previously (17) and chlamydial growth medium (minimal essential medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum and 1% l-glutamine [Gibco BRL, Eggenstein, Germany]) was added to give a ratio of approximately 10 IFU per host cell.

Sera from patients.

Sera were collected from patients with both typical respiratory illnesses, e.g., sore throat, pharyngitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia, and positive C. pneumoniae detection by culture and/or PCR. Isolation of C. pneumoniae was accomplished by centrifugation of clinical specimens from the respiratory tract onto cycloheximide-treated HEp-2 cells as described previously (37, 44). For species identification a monoclonal fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibody against C. pneumoniae was used (C. pneumoniae antigen IFT; Cellabs, Australia). C. pneumoniae DNA detection was performed by a modified nested-PCR protocol (3, 42). Sera were checked with a commercially available immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM Chlamydia MIF test (MRL Diagnostics, Cypress, Calif.) by using four antigen dots, namely, dots for C. pneumoniae TW183, two strains of Chlamydia psittaci (6BC and DD34), serotypes D to K of C. trachomatis, and a noninfected yolk sac preparation. Ten of the sera fulfilled the recommended serological criteria for C. pneumoniae infection and were included in the study (25). Furthermore, a panel of 10 sera was selected from patients with culture- or ligase chain reaction-positive urogenital C. trachomatis infection. Another serum sample was taken from a patient with culture-confirmed ornithosis (10). Control sera were obtained from apparently healthy blood donors either without chlamydial antibodies or with C. pneumoniae IgG antibodies in the range of 1:32 to 1:128, suggestive of past C. pneumoniae infection. A more detailed characterization of the patient sera used in this study is given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of patient sera used and their main reactivities by immunoblot analysis with purified C. pneumoniae TW 183 elementary bodies

| Patient (lane in Fig. 1) | Age/sexa | Clinical picture (wkb) | Chlamydia detection method | MIF

titerc

|

IgG immunoblot reactivity

for bandd:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM | IgG | 70 | 60–62 | 53 | 43 | 40 | 15 | 8–10 | ||||

| Fig. 1Ae | ||||||||||||

| Rei (1) | 43/M | Persistent cough (10) | Culture | 40 | 2,048 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 |

| Smi (2) | 38/F | Sinusitis, bronchitis (4) | Culture | 40 | 256 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + |

| Rch (3) | 39/F | Pneumonia (?) | PCR | <20 | 1,024 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 |

| Wem (4) | 61/F | Sinusitis, pneumonia (4) | PCR | 40 | 2,048 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 |

| Kal (5) | 18/F | Pneumonia (14) | PCR | 20 | 512 | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| Dei (6) | 28/F | Bronchitis (6) | PCR | <20 | 2,048 | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Kle (7) | 12/M | Pneumonia (4) | PCR | 80 | 128 | + | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| Sed (8) | 39/F | Bronchitis (4) | PCR | 80 | 1,024 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| S 11 (9) | 45/F | Persistent cough (26) | PCR | 80 | 1,024 | + | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| S 38 (10) | 15/M | Pharyngitis (16) | Culture | <20 | 512 | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| Fig. 1Bf | ||||||||||||

| Dik (11) | Cervicitis, bronchitis (4) | Culture | <20 | 1,024 | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Swa (12) | Urethritis (?) | LCRg | <20 | 128 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | |

| Bir (13) | Ornithosis (8) | Culture | 40 | 1,024 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | |

| Hbd (14) | Healthy blood donor | NDh | <20 | 64 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

M, male; F, female.

Weeks after onset of symptoms (?, onset unknown).

Reciprocal of the serum dilution from the MIF test for C. pneumoniae.

Bands are identified by kilodalton values. +, reactivity; 0, no reactivity.

Ten sera from patients with C. pneumoniae infection.

Serum from a patient (lane 11) with culture-positive C. trachomatis cervicitis and suspected C. pneumoniae bronchitis, serum (lane 12) representative of 10 sera from patients with urogenital C. trachomatis infection, serum from a patient with ornithosis (lane 13), and serum (lane 14) representative of 10 sera from healthy adult donors with IgG antibody titers, as determined by MIF test, ranging from <32 to 128.

LCR, ligase chain reaction.

ND, not detected.

Sera from mice.

BALB/c mice intranasally infected with C. pneumoniae develop a mild self-limiting pneumonia (35). Histopathological analysis of lung sections 10 days postinfection revealed a polymorphonuclear infiltration in both lungs (data not shown). Chlamydial burden was between 104 and 105 IFU per organ. To obtain highly reactive animal sera, intranasal infection was repeated 4 weeks after the first challenge and blood was taken 1 week later by cardiac puncture. Sera of three mice with IgG antibody titers by MIF test between 1:128 and 1:512 were pooled and stored at −20°C prior to usage.

Murine MAbs.

C. pneumoniae-specific IgG monoclonal antibody (MAb) RR 402 (Washington Research Foundation) and IgG MAb 11A (C. pneumoniae antigen IFT; Cellabs) were used for immunoprecipitation. MAb S25-23, which is directed against the genus-specific epitope of chlamydial LPS, was used for identification of LPS by immunoblot analysis and was a kind gift from H. Brade, Forschungsinstitut Borstel, Borstel, Germany (13).

Immunoblot analysis.

After two washes in 0.22 M sucrose–10 mM NaH2PO4–3.8 mM KH2PO4–5 mM glutamic acid (pH 7.4), the purity of C. pneumoniae elementary bodies was controlled by immunofluorescence microscopy. Chlamydial proteins (10 μg per lane) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in a 12% polyacrylamide gel system according to the method of Laemmli (28). To absorb nonspecific bindings due to cross-reactivities to potentially contaminating host cell proteins in the sample, all sera used for immunoblot analysis were preincubated with HeLa 229 cell lysates at 4°C overnight. In addition, a sample of homogenized HeLa 229 cells with the same protein weight was run in every separation as a control to detect remaining nonspecific bindings which were not removable by preabsorption. After separation, proteins were transferred to an Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride transfer membrane (Millipore). Membranes were blocked with a solution of 3% nonfat dried milk from bovines (Sigma Chemicals, Deisenhofen, Germany) for 2 h and incubated with human C. pneumoniae antisera. After being washed with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20, pH 8.0, the blots were incubated with goat anti-human IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma Chemicals). Color development was observed on the addition of H2O2 and 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma Chemicals) and stopped by rinsing the blots in H2O.

Cell infection, radioactive labeling, and immunoprecipitation.

C. pneumoniae TW 183 was added to HeLa 229 cell monolayers to give approximately a multiplicity of infection of 10, and the monolayers were centrifuged at 1,600 × g for 1 h. After incubation for 1 h at 37° in 5% CO2, supernatants were replaced by Chlamydia infection medium (growth medium supplemented with cycloheximide [2 μg/ml] and antibiotics [vancomycin at 100 μg/ml and gentamicin at 50 μg/ml]). This time was defined as time zero. Chlamydial protein synthesis was determined between 0 and 24, 24 and 48, and 48 and 72 h of the C. pneumoniae developmental cycle in HeLa 229 cells. Radioactive labeling and immunoprecipitation were performed as described previously (41) with slight modifications. Briefly, sets of 1 × 107 to 2 × 107 infected and noninfected cells were washed two times with Chlamydia infection medium without l-methionine and l-cysteine. Cells were pulsed with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine (250 μCi; PRO-MIX; Amersham) for 24 h at 0, 24, and 48 h after infection. To suppress host cell protein synthesis, a cycloheximide concentration of 50 μg per ml of medium was chosen during the period of pulsing. After being pulsed, adherent host cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, to remove [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine which had not been incorporated by host cells. Bacterial proteins were extracted by treating cells with lysis buffer under the protection of leupeptin, aprotinin, and 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoriol (Calbiochem-Novabiochem, Bad Soden, Germany). Lysates were briefly centrifuged at 19,000 × g, and the supernatants containing the 35S-labeled proteins were stored in aliquots of 5 μCi at −20°C. As chlamydial growth depends on the viability of host cells, the metabolic activity of the host cells could not be arrested completely. To minimize nonspecific bindings of patient sera to radiolabeled host cell proteins, thawed supernatants were precleared with C. pneumoniae antibody-negative human sera and protein A-Sepharose beads. The precleared supernatants were incubated with 15 μl of sera from infected humans for 90 min at 4°C and with 100 μl of protein A-Sepharose for an additional 60 min. Patient sera were incubated in parallel with lysates of uninfected HeLa 229 cells to reveal potentially remaining nonspecific immune complexes. After elution of absorbed antigens by boiling the immune complex-bound beads in SDS buffer, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE with a 12% acrylamide gel system and visualized autoradiographically, as described previously (41).

RESULTS

The majority of sera reveal immunoreactivity to the 60- to 62-kDa antigen when examined by immunoblotting.

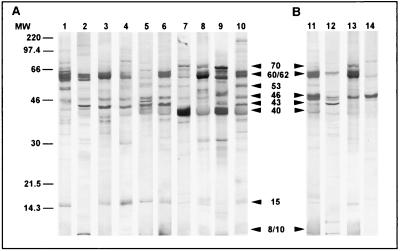

Western blots of purified elementary bodies with sera from C. pneumoniae-infected patients are shown in Fig. 1A, and the most frequent reactivities are summarized in Table 1. Ninety percent of the sera from patients with culture- and/or PCR-confirmed C. pneumoniae infection reacted with the 60- to 62-kDa antigen, which most likely corresponds to OMP2 of C. pneumoniae. In 60% of the sera (Fig. 1A, lanes 5 to 10) a strong but blurred signal was obtained at approximately 40 kDa, suggesting reactivity with the 39.5-kDa MOMP of C. pneumoniae. In 70% of the sera a 43-kDa antigen that migrated as a sharp band near the MOMP was detected. Further reactivities detected by at least 40% of sera were obtained with antigens of approximately 70, 53, and 15 kDa.

FIG. 1.

IgG immunoblots obtained with sera from patients with chlamydial infections diagnosed by culture and/or PCR and MIF serology. Purified C. pneumoniae TW 183 elementary bodies were used for antigen preparation as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Immunoblots of sera from 10 patients (lanes 1 to 10) with respiratory C. pneumoniae infection as characterized in Table 1. Arrowheads indicate the most frequent reactivities. (B) Immunoblots of sera from patients with both urogenital C. trachomatis infection and suspected C. pneumoniae respiratory tract infection (lane 11), C. trachomatis infection (lane 12), and C. psittaci infection (lane 13) and serum from a healthy blood donor (lane 14). Arrowheads indicate the major cross-reactivities observed. Sizes were estimated based on Rainbow colored protein molecular weight markers (Amersham). Molecular weights (MW) are in thousands.

Sera from patients with other chlamydial infections may recognize the 60- to 62- and 40-kDa antigens of C. pneumoniae as well.

C. pneumoniae TW 183 elementary bodies were also reacted with sera of humans with other chlamydial infections to control the specificity of the observed reactions. Figure 1B illustrates the results for representative sera. Eighty percent of the sera from 10 patients with culture- and/or PCR-confirmed C. trachomatis infection weakly recognized either the 60- to 62- or the 40-kDa antigens of C. pneumoniae TW 183 elementary bodies, probably due to well-known genus-specific epitopes of OMP2 and MOMP (an example is given in Fig. 1B, lane 12). Strong and dominant reactivities with C. pneumoniae OMP2 were seen in a patient with cervicitis who additionally showed clinical signs of respiratory infection with elevated C. pneumoniae IgG antibody titers of 1:2,048 (Fig. 1B, lane 11) and in a patient with culture-positive ornithosis showing highly elevated MIF-detected IgG antibodies against all three Chlamydia species (Fig. 1B, lane 13). Further genus-specific reactivities were seen at 70 kDa, and the presence of the 8- to 10-kDa chlamydial LPS was confirmed by reactivity with MAb S25-23 (data not shown).

The 46-kDa antigen is nonspecific for C. pneumoniae infection.

Most of the control sera (80%), which were obtained from adult healthy blood donors, as well as patient sera (100%) recognized a 46-kDa antigen (Fig. 1A and Fig. 1B, lane 14). Strong reactivities against the 60- to 62-kDa protein and the 40-kDa MOMP were lacking in all cases. Faint bands at 60 to 62 and 40 kDa indicating weak OMP2 and MOMP reactions, respectively, were only seen in blood donor sera which exhibited MIF test-determined IgG antibody titers of 1:64 and 1:128, suggestive of a past C. pneumoniae infection (Fig. 1B, lane 14).

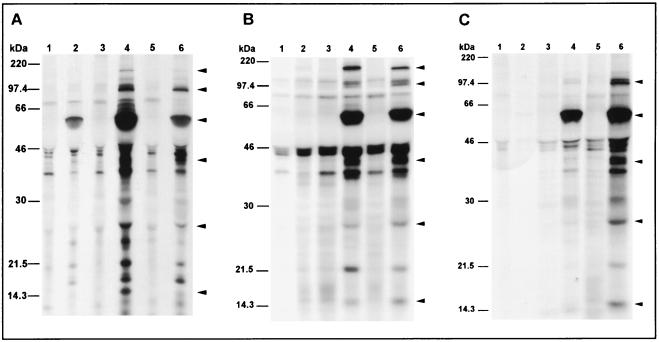

Immunogenic C. pneumoniae antigens are synthesized during the middle and late phases of the cycle.

Newly synthesized C. pneumoniae antigens were radiolabeled and precipitated after 24, 48, and 72 h, covering thereby the complete chlamydial developmental cycle. During the early phase of the developmental cycle (Fig. 2, lanes 2) at best weak signals could be obtained, suggesting that proteins synthesized during the first 24 h of the developmental cycle are of minor immunogenicity or do not incorporate 35S. An intense staining of de novo-synthesized antigens was found in the middle and late phases of the growth cycle; however, growth-specific bands which appeared exclusively at one distinct phase of the chlamydial developmental cycle could be not detected (Fig. 2, lanes 4 and 6). Similar band patterns were obtained for all sera from patients with C. pneumoniae infection. The frequencies of the main reactivities are given in Table 2, and representative autoradiographs of precipitated antigens for sera from patients with culture- or PCR-confirmed C. pneumoniae infection are demonstrated in Fig. 2. Analysis of bands which could be detected by at least 80% of the sera during the middle and/or late phase of the cycle reveals a profile of immunogenic C. pneumoniae proteins with estimated molecular masses of about 160, 97 to 99, 60 to 62, 40, 27, and 15 kDa (Table 2; Fig. 2). These reactivities might correspond to previously described proteins of the chlamydial OMC such as the 97- to 99-kDa OMP4 and OMP5, the 60- to 62-kDa OMP2, the 40-kDa MOMP, and the 15.5-kDa OMP3. A protein with an estimated molecular mass of approximately 160 kDa has not been described in published reports, while the 27-kDa protein might correspond to the Mip-like protein of C. trachomatis.

FIG. 2.

Autoradiographs of SDS-PAGE gels showing a sequential immunoprecipitation of biosynthesized radiolabeled antigens of C. pneumoniae TW 183 0 to 24 h (lanes 2), 24 to 48 h (lanes 4), and 48 to 72 h (lanes 6) after infection of HeLa 229 cells. Precipitation of noninfected host cell antigens (lanes 1, 3, and 5) at the same time points was performed to reveal nonspecific binding of serum antibodies to eukaryotic host cell antigens. Immunoprecipitation was done with sera from one patient representative of patients with culture-positive C. pneumoniae infection (A) and from two patients representative of patients with PCR-positive C. pneumoniae infection (B and C). Arrowheads indicate C. pneumoniae antigens which were detected by at least 80% of the patient sera and which migrated at 160, 97 to 99, 60 to 62, 40, 27, and 15 kDa (Table 2). Sizes were estimated based on 14C-methylated protein molecular weight markers (Amersham).

TABLE 2.

De novo-synthesized C. pneumoniae antigens precipitated by 10 human sera from patients with respiratory C. pneumoniae infection (Table 1; Fig. 1A)a

| C. pneumoniae antigen recognized (kDa) | % Reactive sera at indicated

stage of chlamydial growth cycleb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–24 h p.i. | 24–48 h p.i. | 48–72 h p.i. | |

| ∼160 | 10 | 80 | 70 |

| 97–99 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| 70 | 10 | 30 | 20 |

| 60–62 | 30 | 100 | 100 |

| 40 | 10 | 100 | 100 |

| 30 | 0 | 30 | 30 |

| 27 | 0 | 80 | 80 |

| 20 | 10 | 70 | 70 |

| 15 | 10 | 60 | 80 |

Antigens showing cross-reactivity with eukaryotic host cell antigens are not included. Antigens recognized by at least 80% of the sera are in boldface.

p.i., postinfection.

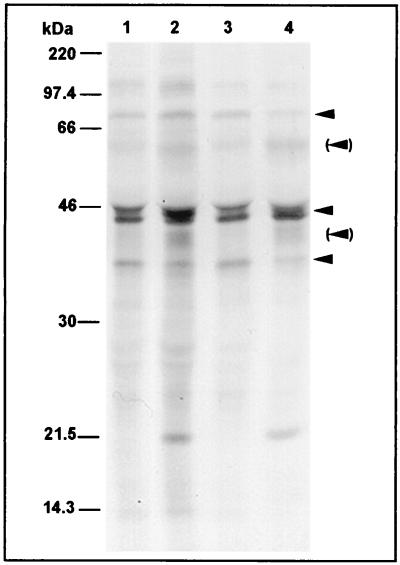

Band patterns of sera from infected patients and healthy blood donors differ significantly.

By analogy with immunoblot analysis, weak reactivities at 40 and 60 to 62 kDa were only obtained with sera of healthy blood donors when sera exhibited MIF test-determined IgG antibody titers of at least 1:64. Strong signals at 40 and 60 to 62 kDa, as well as reactivities with the 160-, 97- to 99-, 27-, and 15-kDa antigens, were not detected. Both control sera and sera from infected patients usually showed a reactivity in a range of 43 to 46 kDa, with both infected and uninfected cells indicating that this reactivity was nonspecific for C. pneumoniae infection (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Autoradiographs of SDS-PAGE gels showing C. pneumoniae (lanes 2 and 4) and host cell antigens (lanes 1 and 3) which were synthesized 24 to 48 h (lanes 1 and 2) and 48 to 72 h (lanes 3 and 4) after infection of HeLa 229 cells and which were precipitated by a representative serum from a healthy donor with a C. pneumoniae IgG antibody titer of 1:64, suggestive of past infection. Arrows indicate the most frequently observed nonspecific reactivities at approximately 75, 43 to 46, and 35 kDa. Arrowheads in parentheses indicate weak reactivities with the 60- to 62- and 40-kDa antigens of C. pneumoniae.

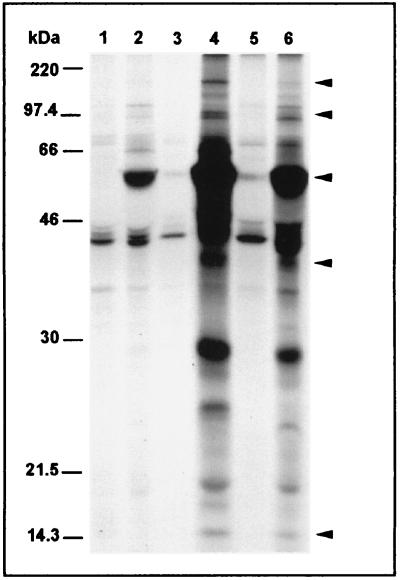

Band patterns of sera from infected patients and BALB/c mice did not differ significantly.

BALB/c mice, which have been used to study cell-mediated immunity in C. pneumoniae-induced pneumonia, were infected experimentally with C. pneumoniae, and pooled sera from mice with histopathological signs of pneumonia were used for immunoprecipitation of biosynthesized chlamydial proteins. A band pattern similar to the patterns obtained from sera of humans with respiratory tract infection was found (Fig. 4).

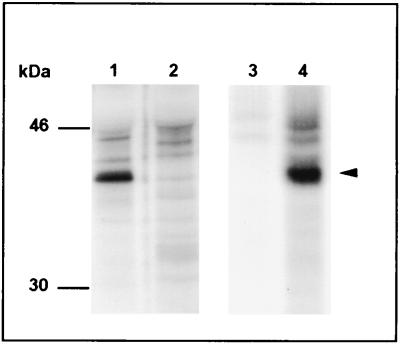

FIG. 4.

Autoradiographs of SDS-PAGE gels showing a sequential immunoprecipitation of C. pneumoniae antigens synthesized 0 to 24 h (lane 2), 24 to 48 h (lane 4), and 48 to 72 h (lane 6) after infection of HeLa 229 cells. Immunoprecipitation was done with pooled serum from three experimentally infected mice. Precipitation of noninfected host cell antigens (lanes 1, 3, and 5) at the same time points was performed to demonstrate nonspecific reactivities. Arrowheads indicate antigens of approximately 160, 97 to 99, 60 to 62, and 15 kDa, which could also be detected frequently by sera from infected humans.

MAbs recognize the 40-kDa protein of C. pneumonia.

Two murine MAbs which have been demonstrated to be species specific for C. pneumoniae by immunofluorescence recognized the 40-kDa antigen when these antibodies were reacted with chlamydial proteins which were synthesized during the middle and late phases of the growth cycle (Fig. 5). However, no reactivity was found when MAbs were reacted with purified elementary bodies in an immunoblot analysis (data not shown), suggesting that conformational epitopes of the MOMP were recognized by these MAbs.

FIG. 5.

Autoradiographs of SDS-PAGE gels showing host cell antigens from C. pneumoniae-infected (lanes 1 and 4) and noninfected (lanes 2 and 3) cells. The antigens were synthesized 24 to 48 h after infection of HeLa 229 cells. Immunoprecipitation was done with murine MAbs RR 402 (lanes 1 and 2) and 11A (lanes 3 and 4). The arrowhead indicates the reactivity of both antibodies with a 40-kDa antigen of C. pneumoniae.

DISCUSSION

The objective was to identify antigens which are recognized by sera of patients infected with C. pneumoniae. We think that the panel of 10 sera used represents sera of truly infected patients because (i) these patients had typical symptoms, (ii) chlamydiae were detected by culture or PCR, and (iii) MIF serology was suggestive of an acute infection according to published recommendations. In order to increase the sensitivity of the detection assay, antigens were labeled metabolically during intracellular growth. Since antigen conformation may affect the reactivity, immunoprecipitation was performed. This procedure enabled us to detect de novo-synthesized proteins. Antigens which do not incorporate 35S-labeled methionine and cysteine or which are not bound by the respective antibody cannot be detected. This might be an explanation for the lack of bands in specimens of the early growth phase. We did not detect bands which were specific for the second and third growth phases.

Based on the band patterns of autoradiographs from precipitated proteins during the middle and late phases of the developmental cycle, we established a profile of immunogenic proteins from C. pneumoniae prototype strain TW 183 which were detected by at least 80% of the sera and which migrated during SDS-PAGE at molecular masses of approximately 160, 97 to 99, 60 to 62, 40, 27, and 15 kDa. Bands with molecular masses of 60 to 62, 40, and 15 kDa were observed in both immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation experiments.

The 60- to 62-kDa antigen, which is strongly upregulated after 24 to 48 h of host cell infection, showed up clearly as a major immunogen in both C. pneumoniae-infected patients and mice, as well as in patients infected with other chlamydial species. In previous work it was shown that the cysteine-rich proteins of the chlamydial outer membrane are synthesized late in the cycle when reticulate bodies have begun to reorganize back to elementary bodies (11, 16, 33). In contrast, the 60-kDa chlamydial GroEL incorporates 35S early (2 to 8 h postinfection) in its biosynthesis, with a decrease of protein synthesis from 26 to 30 h postinfection (29). Based on these observations, we suggest that the 60- to 62-kDa protein detected by all sera in the middle and late phases of the growth cycle probably corresponds to the cysteine-rich OMP2 but not to the GroEl homolog, which also migrates at approximately 60 kDa in SDS-PAGE. The cysteine-rich OMP2 is thought to constitute the structural integrity of chlamydial elementary bodies and contains both sequences and antigenic determinants shared with proteins from other Chlamydia spp. (11, 31, 32, 34). Our data confirm and extend findings from Mygind et al., who suggested, on the basis of the reactivity of MIF-defined patient sera to truncated fusion proteins, that the 60- to 62-kDa OMP2 was a major immunogen in both C. pneumoniae- and C. trachomatis-infected patients (32).

Weak reactivity of patient sera in immunoblotting, failure to establish neutralizing antibodies, and lack of murine MAbs that recognize MOMP by immunoblot analysis have led to the assumption that the C. pneumoniae MOMP, at least in its linear form, is not a major target of the humoral immune response in C. pneumoniae infection (7, 26, 36). Contradicting results, however, were obtained by others (19, 21). Loss of reactivity by conformational changes and higher sensitivity might explain the detection of the antigen by immunoprecipitation but not by immunoblotting with murine species-specific MAbs. Our findings indicate that the biosynthesized, native 40-kDa MOMP is recognized consistently by sera from C. pneumoniae-infected patients and suggest that the native 40-kDa MOMP may be better recognized than the denatured protein.

A 15.5-kDa cysteine-rich protein was found in the OMC of C. pneumoniae (31). This protein is comparable in molecular mass to the cysteine-rich OMP3 of 12.5 to 15.5 kDa from C. trachomatis (9). The immunogenic role of the 15.5-kDa protein in C. pneumoniae infection has not been elucidated until now, most probably because at best only faint bands are detectable by immunoblot analysis. In our study the detection sensitivity was increased by metabolic radiolabeling of biosynthesized chlamydial proteins. The majority of sera precipitated a protein with a molecular mass of 15 kDa in the middle and/or late phase of the life cycle, indicating that OMP3 of C. pneumoniae may be also a target of the humoral immune response in C. pneumoniae infection. In addition, bands of approximately 160, 97 to 99, and 27 kDa were detected by metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitation but not by immunoblotting. The 27-kDa antigen could be a homolog to the Mip-like protein of C. trachomatis, which is thought to be important for optimal initiation of chlamydial infections (30), while the 160-kDa antigen could correspond to the pmpD-encoded OMP with a predicted molecular mass of 160 kDa; pmpD has been identified as a gene in C. trachomatis (40).

In a recent paper two novel genes encoding 97- to 99-kDa surface-located OMPs (OMP4 and OMP5) of C. pneumoniae have been identified (23). Conformational epitopes of OMP4 seem to be the target of the humoral immune response in experimentally infected mice, since this protein was detectable by immunoblotting only when it was not fully denatured. This is in agreement with our findings, which revealed a 97- to 99-kDa band by immunoprecipitation, but not by immunoblotting. In addition, we could show that this antigen is also immunogenic in naturally infected humans.

We conclude from our data that the 60- to 62-kDa protein of C. pneumoniae represents a major immunogen in patients with respiratory C. pneumoniae infection. In addition, C. pneumoniae proteins of 97 to 99, 40, and 15.5 kDa, which most probably correspond to well-characterized components of the chlamydial OMC, along with proteins of approximately 160 and 27 kDa seem to have immunogenic importance. Further work is needed to clarify if some of these antigens are also suitable for a species-specific or for a genus-specific serodiagnosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kenneth Persson, Department of Clinical Virology, General Hospital Malmo, Malmo, Sweden, and Holger Blenk, Institut Prokaryon, Nuremberg, Germany for supplying sera from Chlamydia-infected individuals. We are grateful to Sonja Weiß for excellent technical assistance.

Part of the work has been supported by a grant from the Sonderforschungsbereich 451 (SFB 451 to A.E. and R.M.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Black C M. Current methods of laboratory diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:160–184. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.1.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black C M, Johnson J E, Farshy C E, Brown T M, Berdal B P. Antigenic variation among strains of Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1312–1316. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.7.1312-1316.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boman J, Allard A, Persson K, Lundborg M, Juto P, Wadell G. Rapid diagnosis of respiratory Chlamydia pneumoniae infection by nested touchdown polymerase chain reaction compared with culture and antigen detection by EIA. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1523–1526. doi: 10.1086/516492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brade H, Brade L, Nano F E. Chemical and serological investigations on the genus-specific lipopolysaccharide epitope of Chlamydia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2508–2512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brade L, Brunnemann H, Ernst M, Fu Y, Holst O, Kosma P, Naher H, Persson K, Brade H. Occurrence of antibodies against chlamydial lipopolysaccharide in human sera as measured by ELISA using an artificial glycoconjugate antigen. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1994;8:27–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1994.tb00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caldwell H D, Kromhout J, Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1981;31:1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell L A, Kuo C C, Grayston J T. Structural and antigenic analysis of Chlamydia pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1990;58:93–97. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.93-97.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell L A, Kuo C C, Wang S P, Grayston J T. Serological response to Chlamydia pneumoniae infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1261–1264. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1261-1264.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke I N, Ward M E, Lambden P R. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of a developmentally regulated cysteine-rich outer membrane protein from Chlamydia trachomatis. Gene. 1988;71:307–314. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Essig A, Zucs P, Susa M, Wasenauer G, Mamat U, Hetzel M, Vogel U, Wieshammer S, Brade H, Marre R. Diagnosis of ornithosis by cell culture and polymerase chain reaction in a patient with chronic pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1495–1497. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.6.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everett K D, Hatch T P. Architecture of the cell envelope of Chlamydia psittaci 6BC. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:877–882. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.877-882.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freidank H M, Herr A S, Jacobs E. Identification of Chlamydia pneumoniae-specific protein antigens in immunoblots. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:947–951. doi: 10.1007/BF01992171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu Y, Baumann M, Kosma P, Brade L, Brade H. A synthetic glycoconjugate representing the genus-specific epitope of chlamydial lipopolysaccharide exhibits the same specificity as its natural counterpart. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1314–1321. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1314-1321.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaydos C A, Roblin P M, Hammerschlag M R, Hyman C L, Eiden J J, Schachter J, Quinn T C. Diagnostic utility of PCR-enzyme immunoassay, culture, and serology for detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:903–905. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.903-905.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grayston J T, Campbell L A, Kuo C C, Mordhorst C H, Saikku P, Thom D H, Wang S P. A new respiratory tract pathogen: Chlamydia pneumoniae strain TWAR. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:618–625. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatch T P, Miceli M, Sublett J E. Synthesis of disulfide-bonded outer membrane proteins during the developmental cycle of Chlamydia psittaci and Chlamydia trachomatis. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:379–385. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.2.379-385.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinemann M, Susa M, Simnacher U, Marre R, Essig A. Growth of Chlamydia pneumoniae induces cytokine production and expression of CD14 in a human monocytic cell line. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4872–4875. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4872-4875.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyman C L, Roblin P M, Gaydos C A, Quinn T C, Schachter J, Hammerschlag M R. Prevalence of asymptomatic nasopharyngeal carriage of Chlamydia pneumoniae in subjectively healthy adults: assessment by polymerase chain reaction-enzyme immunoassay and culture. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1174–1178. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.5.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iijima Y, Miyashita N, Kishimoto T, Kanamoto Y, Soejima R, Matsumoto A. Characterization of Chlamydia pneumoniae species-specific proteins immunodominant in humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:583–588. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.583-588.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson L A, Campbell L A, Schmidt R A, Kuo C C, Cappuccio A L, Lee M J, Grayston J T. Specificity of detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae in cardiovascular atheroma: evaluation of the innocent bystander hypothesis. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1785–1790. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jantos C A, Heck S, Roggendorf R, Sen-Gupta M, Hegemann J H. Antigenic and molecular analyses of different Chlamydia pneumoniae strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:620–623. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.620-623.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kauppinen M, Saikku P. Pneumonia due to Chlamydia pneumoniae: prevalence, clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(Suppl. 3):5244–5252. doi: 10.1093/clind/21.supplement_3.s244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knudsen K, Madsen A S, Mygind P, Christiansen G, Birkelund S. Identification of two novel genes encoding 97- to 99-kilodalton outer membrane proteins of Chlamydia pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1999;67:375–383. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.375-383.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo C C, Grayston J T, Campbell L A, Goo Y A, Wissler R W, Benditt E P. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR) in coronary arteries of young adults (15–34 years old) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6911–6914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo C C, Jackson L A, Campbell L A, Grayston J T. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR) Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:451–461. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kutlin A, Roblin P M, Hammerschlag M R. Antibody response to Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in children with respiratory illness. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:720–724. doi: 10.1086/514223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kutlin A, Tsumura N, Emre U, Roblin P M, Hammerschlag M R. Evaluation of chlamydia immunoglobulin M (IgM), IgG, and IgA rELISAs Medac for diagnosis of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:213–216. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.2.213-216.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundemose A G, Birkelund S, Larsen P M, Fey S J, Christiansen G. Characterization and identification of early proteins in Chlamydia trachomatis serovar L2 by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2478–2486. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2478-2486.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lundemose A G, Rouch D A, Birkelund S, Christiansen G, Pearce J H. Chlamydia trachomatis Mip-like protein. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2539–2548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melgosa M P, Kuo C C, Campbell L A. Outer membrane complex proteins of Chlamydia pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;112:199–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mygind P, Christiansen G, Persson K, Birkelund S. Analysis of the humoral immune response to Chlamydia outer membrane protein 2. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:313–318. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.3.313-318.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newhall W J. Biosynthesis and disulfide cross-linking of outer membrane components during the growth cycle of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1987;55:162–168. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.162-168.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newhall W J, Batteiger B, Jones R B. Analysis of the human serological response to proteins of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1982;38:1181–1189. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.3.1181-1189.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Penttila J M, Anttila M, Puolakkainen M, Laurila A, Varkila K, Sarvas M, Makela P H, Rautonen N. Local immune responses to Chlamydia pneumoniae in the lungs of BALB/c mice during primary infection and reinfection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5113–5118. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5113-5118.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson E M, Cheng X, Qu Z, de la Maza L M. Characterization of the murine antibody response to peptides representing the variable domains of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3354–3359. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3354-3359.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roblin P M, Dumornay W, Hammerschlag M R. Use of HEp-2 cells for improved isolation and passage of Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1968–1971. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.1968-1971.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saikku P. The epidemiology and significance of Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Infect. 1992;25(Suppl. 1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/0163-4453(92)91913-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saikku P, Leinonen M, Mattila K, Ekman M R, Nieminen M S, Makela P H, Huttunen J K, Valtonen V. Serological evidence of an association of a novel Chlamydia, TWAR, with chronic coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1988;ii:983–986. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90741-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stephens R S, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov R L, Zhao Q, Koonin E V, Davis R W. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science. 1998;282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Susa M, Hacker J, Marre R. De novo synthesis of Legionella pneumophila antigens during intracellular growth in phagocytic cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1679–1684. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1679-1684.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tong C Y, Sillis M. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae and Chlamydia psittaci in sputum samples by PCR. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46:313–317. doi: 10.1136/jcp.46.4.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watson M W, Lambden P R, Everson J S, Clarke I N. Immunoreactivity of the 60 kDa cysteine-rich proteins of Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia psittaci and Chlamydia pneumoniae expressed in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1994;140:2003–2011. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong K H, Skelton S K, Chan Y K. Efficient culture of Chlamydia pneumoniae with cell lines derived from the human respiratory tract. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1625–1630. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1625-1630.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong Y K, Gallagher P J, Ward M E. Chlamydia pneumoniae and atherosclerosis. Heart. 1999;81:232–238. doi: 10.1136/hrt.81.3.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]