ABSTRACT

The proteasome is a promising target for antimalarial chemotherapy. We assessed ex vivo susceptibilities of fresh Plasmodium falciparum isolates from eastern Uganda to seven proteasome inhibitors: two asparagine ethylenediamines, two macrocyclic peptides, and three peptide boronates; five had median IC50 values <100 nM. TDI8304, a macrocylic peptide lead compound with drug-like properties, had a median IC50 of 16 nM. Sequencing genes encoding the β2 and β5 catalytic proteasome subunits, the predicted targets of the inhibitors, and five additional proteasome subunits, identified two mutations in β2 (I204T, S214F), three mutations in β5 (V2I, A142S, D150E), and three mutations in other subunits. The β2 S214F mutation was associated with decreased susceptibility to two peptide boronates, with IC50s of 181 nM and 2635 nM against mutant versus 62 nM and 477 nM against wild type parasites for MMV1579506 and MMV1794229, respectively, although significance could not be formally assessed due to the small number of mutant parasites with available data. The other β2 and β5 mutations and mutations in other subunits were not associated with susceptibility to tested compounds. Against culture-adapted Ugandan isolates, two asparagine ethylenediamines and the peptide proteasome inhibitors WLW-vinyl sulfone and WLL-vinyl sulfone (which were not studied ex vivo) demonstrated low nM activity, without decreased activity against β2 S214F mutant parasites. Overall, proteasome inhibitors had potent activity against P. falciparum isolates circulating in Uganda, and genetic variation in proteasome targets was uncommon.

KEYWORDS: Plasmodium falciparum, antimalarial agents, proteasome

INTRODUCTION

Malaria, particularly disease caused by Plasmodium falciparum, remains a huge problem, and its control is challenged by resistance to most available therapies (1). New antimalarial drugs, ideally directed against new targets, are needed. One potential target is the proteasome, a protein degradation complex of eukaryotes and actinomycetes that degrades proteins targeted for removal after tagging with ubiquitin or other protein tags (2). A proteasome complex is composed of multi-subunit structures, generally a 20S core particle and one or two 19S regulatory particles on one or both ends of the 20S barrel (2). The 19S regulatory particle recognizes ubiquitinated proteins and transfers them to the 20S core particle for degradation (2). The proteasome has been validated as a target for drugs to treat multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma, and three proteasome inhibitors, bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib, are approved for these indications (3). Additionally, the proteasomes of pathogens have been identified as potential targets for drugs against a number of infectious diseases, including those caused by bacteria and protozoan parasites (4).

In eukaryotes, the 20S core particle contains 14 α and 14 β subunits arranged in a α7β7β7α7 barrel-shaped complex, with 7 different α subunits, including the α-type-6 subunit, forming the outer ring, and 7 different β subunits forming the inner rings. Outer rings regulate the entrance of protein substrates, and proteolytic activity exists in the β rings (5). Only β1, β2, and β5 are catalytically active, with caspase-like, trypsin-like, and chymotrypsin-like proteolytic activities, respectively (6), and the four noncatalytic subunits (β3, β4, β6, and β7) function in assembly and provide structural support for the proteasome complex (7). The RPN10 subunit in the 19S regulatory particle is an essential canonical ubiquitin receptor that recognizes multiubiquitin chains (8). The C-terminal ubiquitin interacting motif of this subunit identifies ubiquinated substrates to shuttle to the proteasome (2, 5). The 19S regulatory particle contains a 19S PfRPT4 subunit, which is an ATPase located at the base of the 19S particle that interacts with the α-ring of the core particle (5). PF3D7_0808300 encodes a putative P. falciparum ubiquitin regulatory protein (9); increased copy number was associated in vitro with low grade resistance to WLL-vinyl sulfone (WLL-VS) and WLW-VS (10).

The P. falciparum proteasome is similar to that of other eukaryotes, with moderate homology between human and P. falciparum catalytic subunits (27% identity for β1, 53% for β2, and 51% for β5; [11]), but differences in structure and substrate specificity have facilitated the design of P. falciparum-targeted inhibitors. Among proteasome inhibitors that have been studied for the treatment of malaria are asparagine ethylenediamines (12), peptide vinyl sulfones (13), and peptide boronates (14, 15). Proteasome inhibitors are typically selective for a particular catalytic subunit, but some can act against multiple subunits (12, 16). Asparagine ethylenediamines are noncovalent, reversible inhibitors that specifically target the β5 subunit (12). Peptide boronates are covalent and slowly reversible inhibitors, and a validated class, with two FDA approved drugs, bortezomib and ixazomib (3, 15). Peptide vinyl sulfones are covalent and irreversible inhibitors, including WLL-VS, which targets the β2 and β5 subunits, and WLW-VS, which targets the β2 subunit (17). Peptide epoxyketones are another validated class of proteasome inhibitors, with one FDA-approved drug (18). Compounds from all of these classes have been developed to selectively target the P. falciparum proteasome over its human counterpart (17, 19, 20).

In considering the P. falciparum proteasome as a target for antimalarials, it is important to characterize naturally occurring variation in inhibitor susceptibility among circulating parasites. We therefore measured ex vivo susceptibilities of fresh Ugandan isolates to a range of proteasome inhibitors. We also sequenced target P. falciparum proteasome subunits and explored associations between identified genetic polymorphisms and inhibitor susceptibilities of Ugandan parasites.

RESULTS

Ex vivo susceptibilities of Ugandan P. falciparum isolates to proteasome inhibitors.

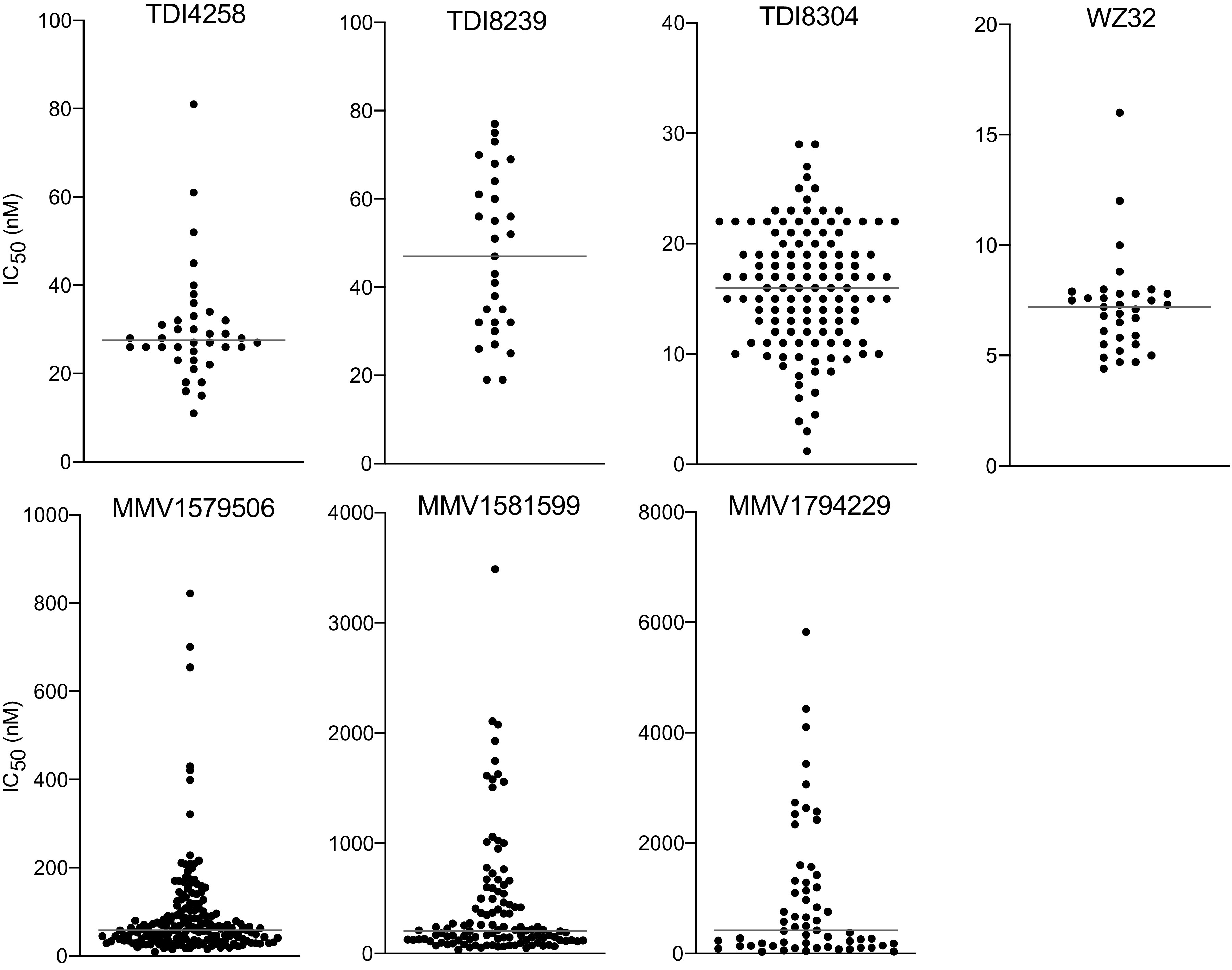

We characterized the ex vivo susceptibilities of fresh Ugandan isolates to 7 proteasome inhibitors; 29 to 234 different isolates were studied per inhibitor, with differences in the number of isolates studied due to varied availability of different inhibitors over time (Table 1). Five of the compounds had median IC50 values <100 nM (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Proteasome inhibitors studieda

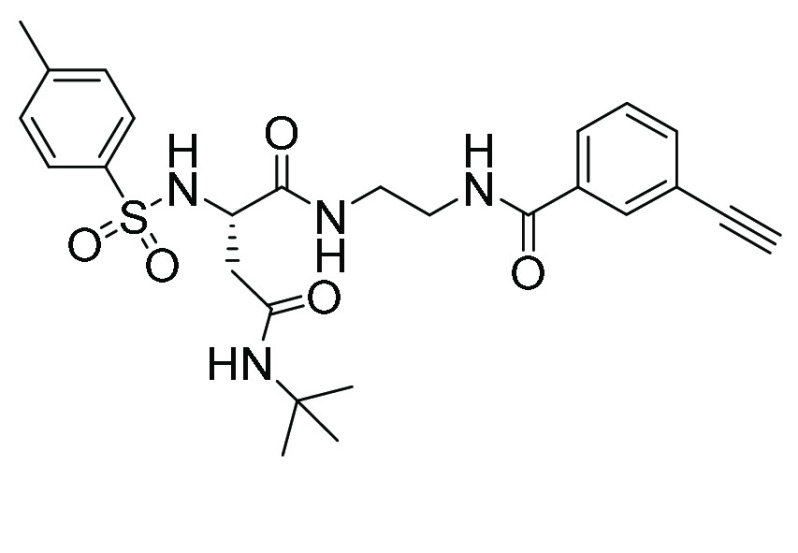

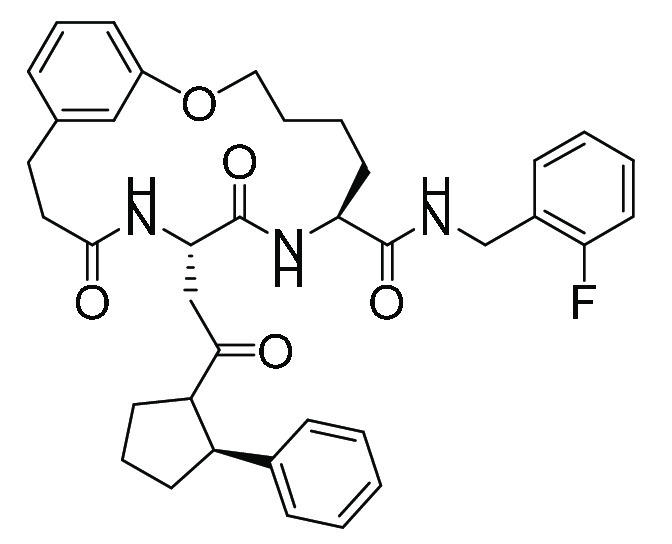

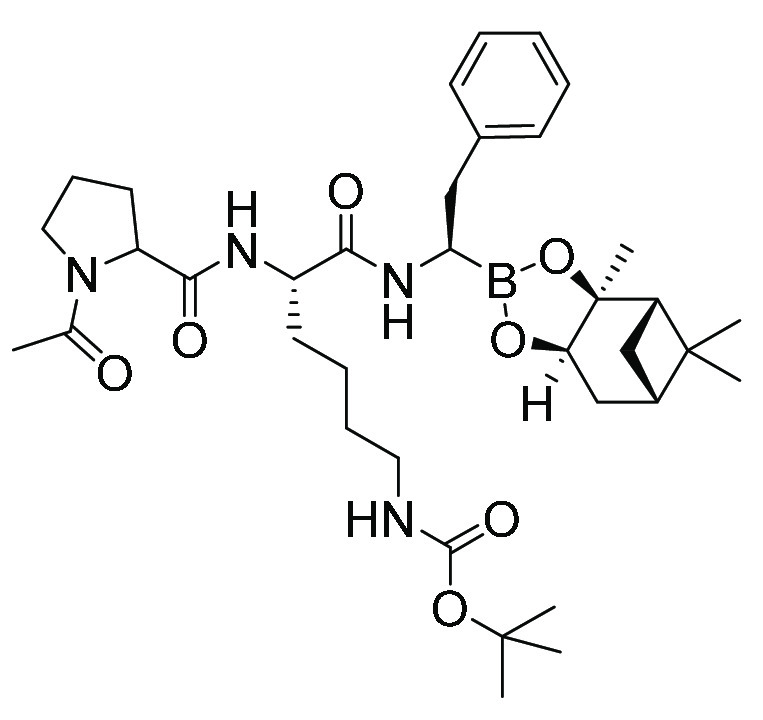

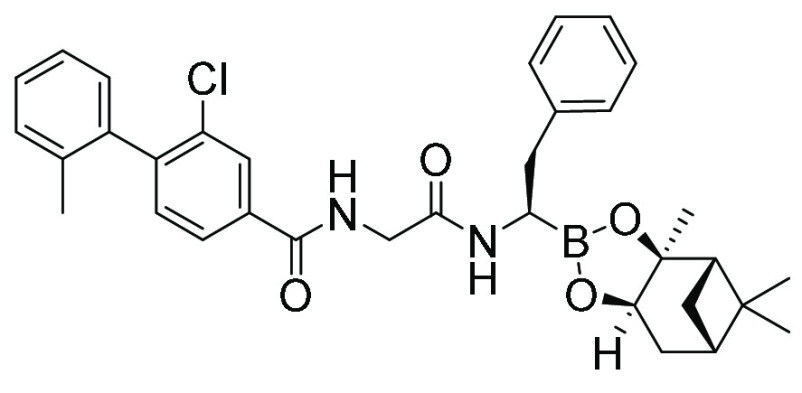

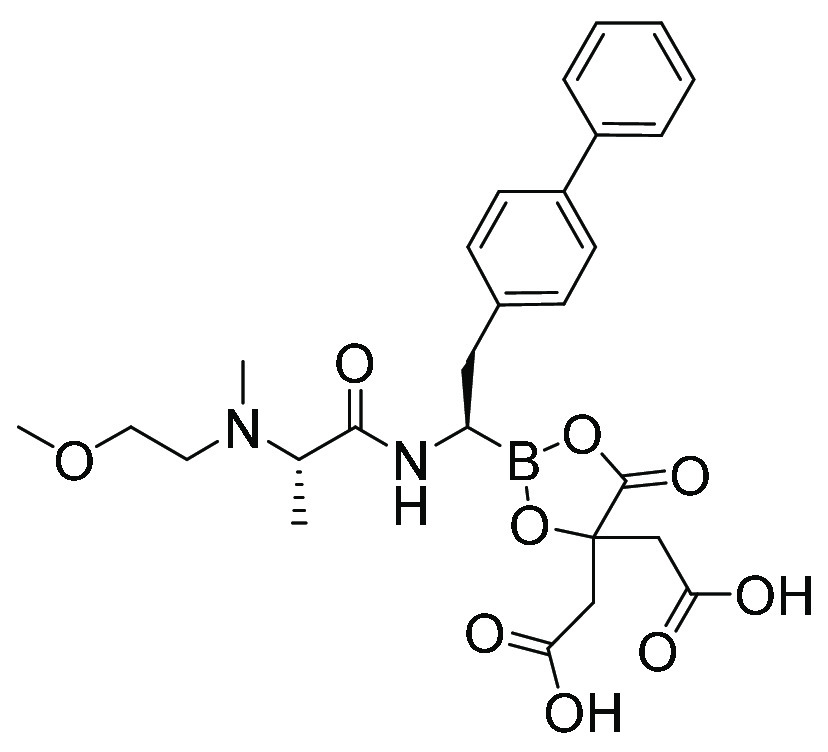

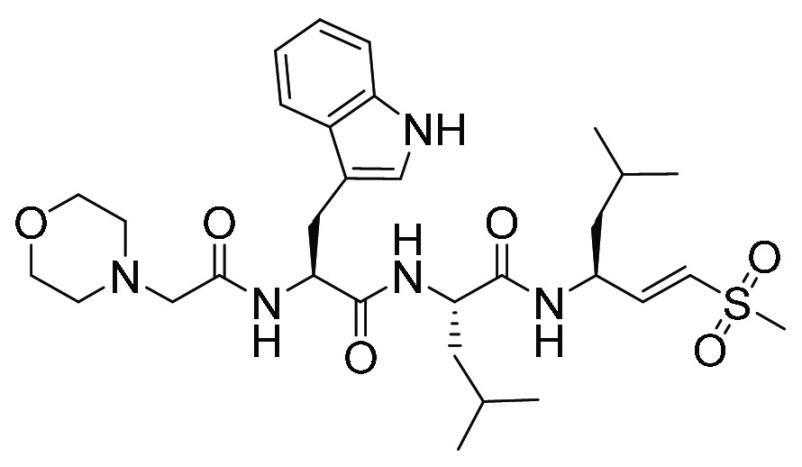

| Compound | Chemical class | Structure | Isolates studied ex vivo |

Ex vivo IC50 (median, nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WZ32 (12, 21, 22) | Asn ethylenediamine |

|

33 | 7.3 |

| TDI4258 (12, 21, 22) | Asn ethylenediamine |

|

38 | 28 |

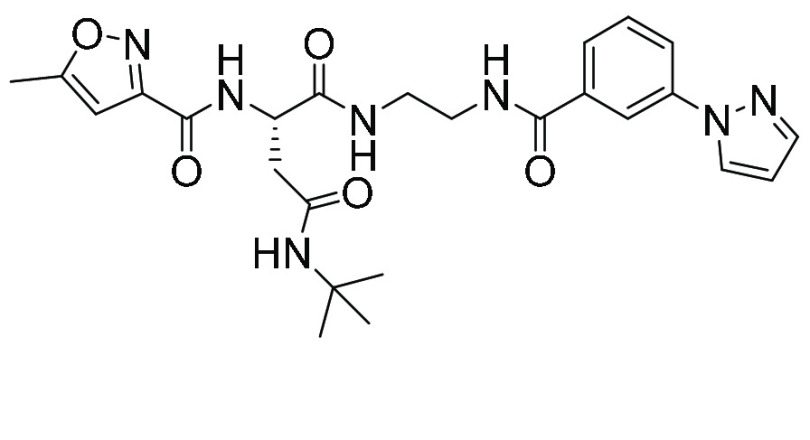

| TDI8239 (25) | Macrocyclic peptide |

|

29 | 49 |

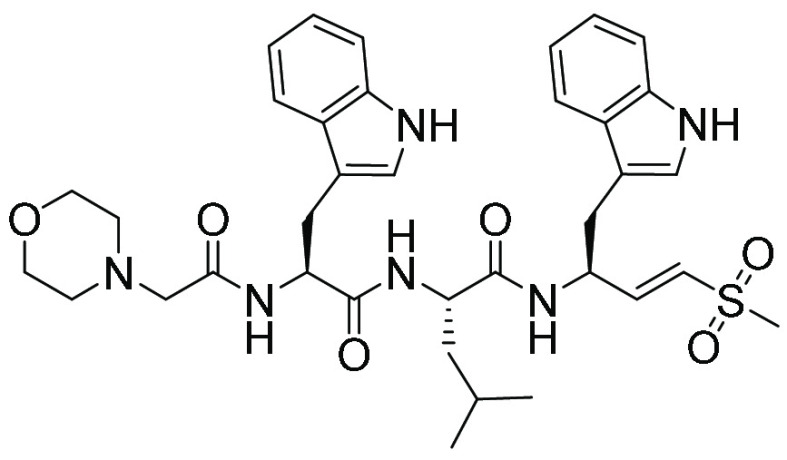

| TDI8304 (12, 21, 22) | Macrocyclic peptide |

|

195 | 16 |

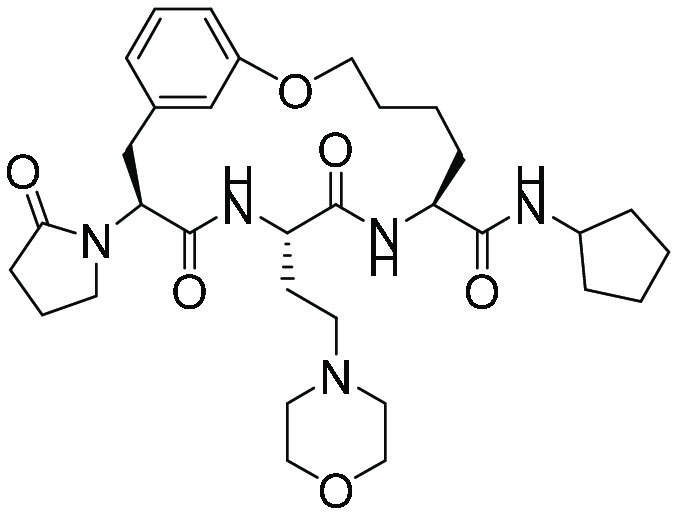

| MMV1579506 | Peptide boronate |

|

234 | 58 |

| MMV1581599 | Peptide boronate |

|

127 | 404 |

| MMV1794229 (19) | Peptide boronate |

|

126 | 206 |

| WLL-VS (17) | Peptide vinyl sulfone |

|

NS | NS |

| WLW-VS (17) | Peptide vinyl sulfone |

|

NS | NS |

aNS, not studied against ex vivo samples.

FIG 1.

Susceptibilities of Ugandan P. falciparum isolates to proteasome inhibitors. Results for each isolate are represented by a dot. Horizontal lines indicate median IC50s.

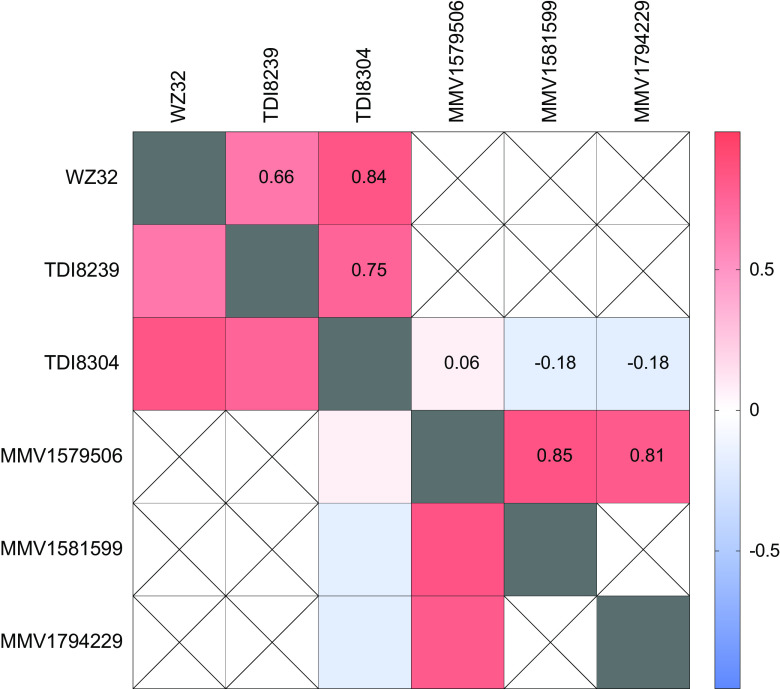

We assessed correlations between potencies of tested compounds to gain insight into potential shared mechanisms of action or resistance, but different compounds were studied over time, and correlations were only possible for compounds studied against the same isolates. Spearman coefficients generally showed positive (r > 0.6) correlations between compounds of the same chemical class (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Heat map demonstrating correlations between susceptibilities of Ugandan isolates to different compounds. Spearman’s coefficients (r) are indicated numerically and by the color scale. Crossed-out fields represent compounds not studied in parallel, such that correlations could not be measured.

Associations between P. falciparum proteasome subunit polymorphisms and ex vivo susceptibilities to proteasome inhibitors.

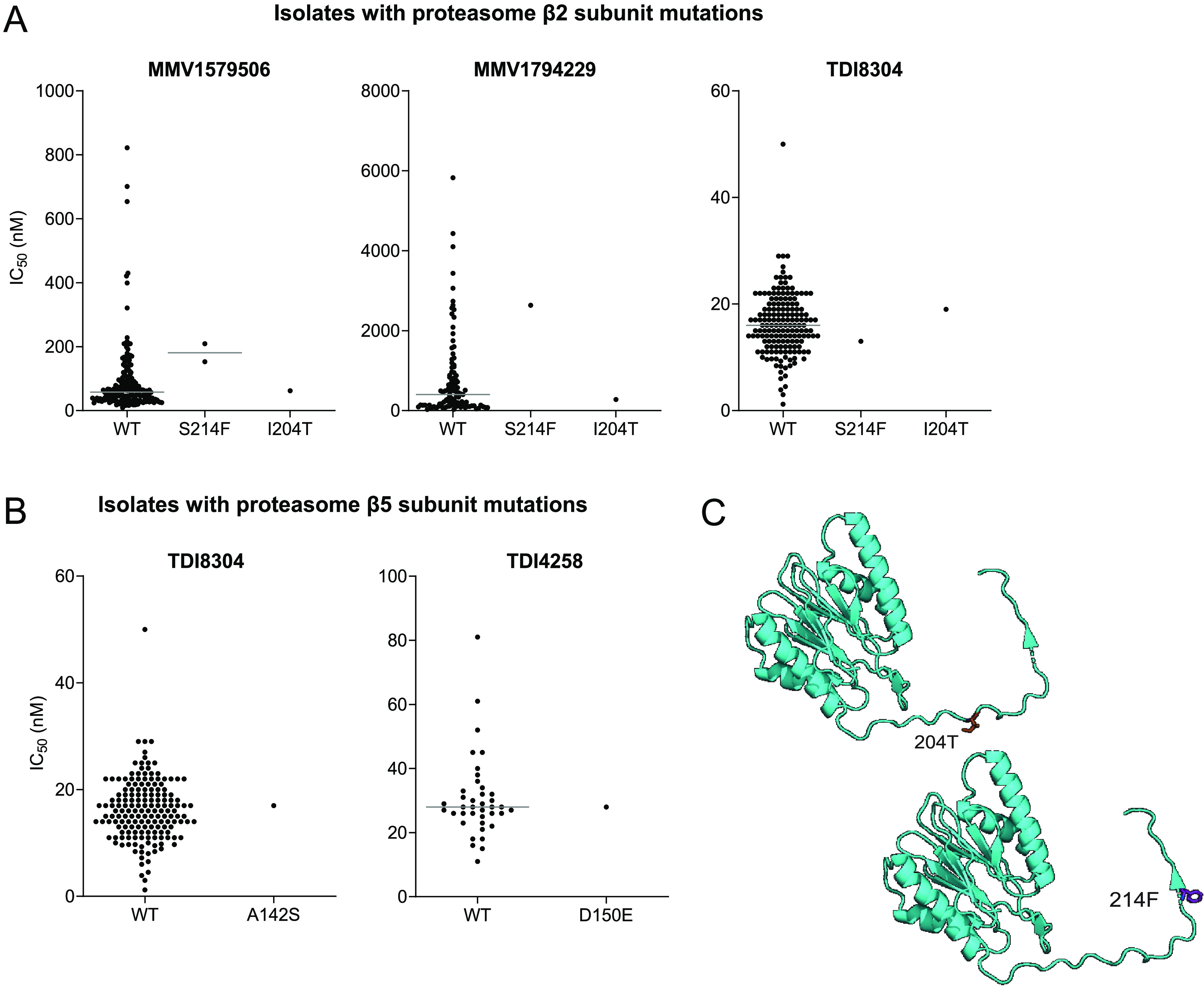

We sequenced genes encoding proteasome subunits to assess associations between sequence polymorphisms and drug susceptibility phenotypes (Table 2). The β2 subunit was sequenced in 726 isolates. Four isolates with β2 subunit nonsynonymous SNPs were identified; one with a I204T mutation and three with a S214F mutation, each a mixed isolate with both wild type and mutant sequences. Both of these mutations are located in the C-terminal tail of the β2 subunit (Fig. 3). Susceptibilities for three of these isolates were available for MMV1579506, and for two of the isolates for MMV1794229 and TDI8304. The β2 S214F mutation was associated with decreased susceptibility to two peptide boronates (IC50 181 nM and 2635 nM against mutant in all cases mixed isolates) versus 62 nM and 477 nM against wild type parasites for MMV1579506 and MMV1794229, respectively, but not to TDI8304 (IC50 13 nM against mutant versus 17 nM against wild type parasites), although analyses were limited by the small number of mutant parasites available for study (Fig. 3).

TABLE 2.

Mutations identified in proteasome subunits of Ugandan P. falciparum isolates

| Proteasome subunit | Polymorphism | Isolates sequenced | Isolates with IC50 data | Median IC50 (nM) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WZ32 | TDI 4258 |

TDI 8239 |

TDI 8304 |

MMV 1579506 |

MMV 1581599 |

MMV 1794229 |

||||

| β2 | - | 722 | 25–209 | 7.0 | 28 | 45 | 17 | 62 | 207 | 477 |

| β2 | S214F | 3 | 1–2 | -a | - | - | 13 | 181 | - | 2635 |

| β2 | I204T | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 19 | 62 | - | 276 |

| β5 | - | 781 | 24–228 | 7.0 | 28 | 35 | 15 | 57 | 145 | 406 |

| β5 | A142S | 4 | 1 | - | - | - | 17 | - | - | - |

| β5 | D150E | 1 | 1 | - | 28 | - | - | - | - | - |

| β6 | - | 123 | 32–123 | 6.0 | 27 | 35 | 15 | 57 | 145 | 477 |

| 19S PfRPT4 | - | 893 | 29–232 | 7.2 | 28 | 47 | 16 | 58 | 209 | 553 |

| α-type-6 | - | 893 | 29–232 | 7.2 | 28 | 47 | 16 | 58 | 209 | 553 |

| RPN10 | - | 346 | 12–87 | 7.3 | 27 | 48 | 16 | 64 | 228 | 569 |

| RPN10 | T225S | 213 | 12–60 | 7.0 | 28 | 54 | 16 | 61 | 210 | 616 |

| RPN10 | E380L | 274 | 4–52 | 7.8 | 27 | 41 | 16 | 49 | 163 | 614 |

| PF3D7_0808300 | - | 486 | 16–131 | 7.2 | 28 | 53 | 15 | 56 | 193 | 668 |

| PF3D7_0808300 | M144I | 141 | 4–38 | 6.9 | 27 | 45 | 17 | 57 | 240 | 401 |

Dashes indicate that no values were available.

FIG 3.

Susceptibilities of mutant P. falciparum isolates to proteasome inhibitors. Susceptibilities of isolates with β2 (A) and β5 (B) wild type (WT) or mutant sequences are shown. Results for individual isolates are represented by dots. Horizontal bars indicate median IC50 values. C. Structural model of the β2 subunit with the I204T and S214F mutations indicated in purple.

The β5 subunit was sequenced in 786 isolates. We identified 4 mixed isolates with a A142S polymorphism, one mixed isolate with a D150E polymorphism, and 10 isolates with a V2I polymorphism (one pure mutant and nine mixed isolates; as this amino acid is not part of the mature β5 subunit after amino-terminal cleavage, these isolates were not further analyzed). One isolate with the A142S polymorphism and one with the D150E polymorphism had IC50 data available for TDI8304 and TDI4258; the polymorphisms did not appear to be associated with altered inhibitor susceptibility (Fig. 3).

We also sequenced other P. falciparum proteasome components and searched for associations between identified polymorphisms and susceptibility to inhibitors (Table 2). No polymorphisms were identified in the fourth exon of the β6 subunit, which encodes a protein segment adjacent to the β5 subunit in the P. falciparum proteasome (123 isolates sequenced), in the 19S PfRPT4 subunit (893 isolates), or in the α-type-6 subunit (893 isolates). Of 833 isolates with the RPN10 subunit sequenced, 213 had a T225S polymorphism and 274 had a E380L polymorphism. These polymorphisms were not associated with altered susceptibility to any of the tested inhibitors. Of 627 isolates with PF3D7_0808300 sequenced, 141 had an M144I polymorphism. This polymorphism was not associated with altered susceptibility to any of the tested inhibitors.

Susceptibility of culture adapted parasites with the β2 S214F mutation to proteasome inhibitors.

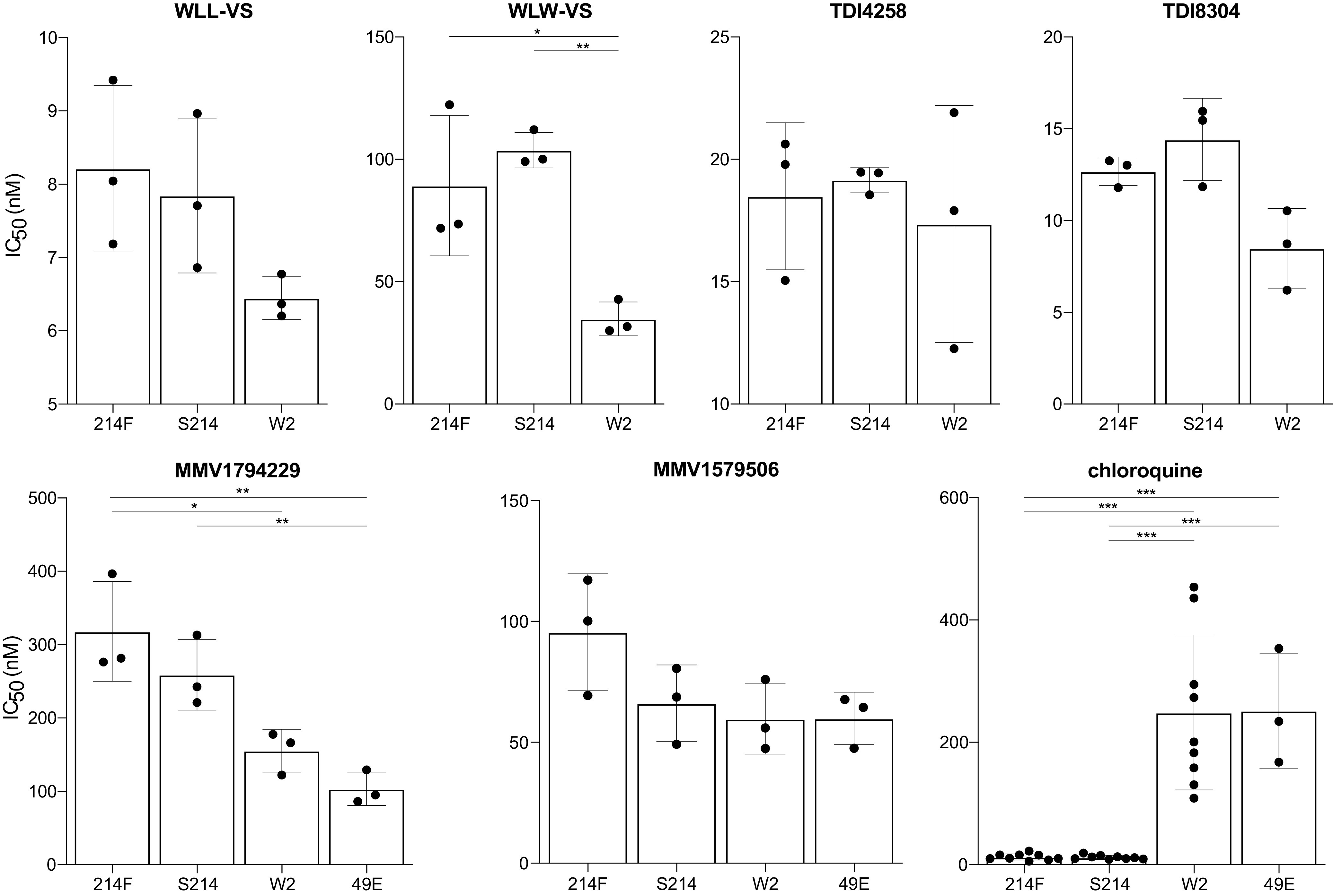

To further study the relevance of the β2 S214F mutation, which was associated with decreased susceptibility to MMV1579506 and MMV1794229 in fresh Ugandan isolates, we measured inhibitor susceptibilities of a culture adapted Ugandan clone with the wild type β2 sequence; a culture adapted Ugandan isolate, which was pure β2 214F mutant after culture adaptation; a laboratory clone derived from the V1/S K13C580Y strain that was selected for the β2 49E mutation (10), and strain W2, which has wild type β2 sequence. These studies included TDI4258, TDI8304, MMV1579506, and MMV1794229, and also two peptide vinyl sulfones targeting the β2 (WLW-VS) and β2/β5 (WLL-VS) subunits that were not available for earlier ex vivo studies against Ugandan isolates. Susceptibilities to WLW-VS, WLL-VS, TDI4258, TDI8304, MMV1579506 and MMV1794229 did not differ between Ugandan β2 214 wild type and mutant parasites (mean IC50 values 90.7, 8.2, 18.5, 14.4, 93.7, and 309 nM against mutant versus 104, 7.8, 19.2, 12.7, 66.2, and 259 nM against wild type, respectively; Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Susceptibilities of β2 mutant parasites to β2 and β5 subunit inhibitors. Each point represents an independent experiment, for a total of three independent biological replicates, with two technical replicates for β2 mutant (214F) and wild type (S214) Ugandan isolates, a laboratory mutant (49E) derived from V1/S K13C580Y, and control strain W2. The histograms show mean IC50s with standard deviations. Significant comparisons are indicated as * <0.5; ** <0.01; and *** <0.001.

DISCUSSION

We studied susceptibilities of fresh Ugandan P. falciparum isolates to a panel of proteasome inhibitors and searched for associations between susceptibilities and genetic polymorphisms in proteasome targets. A number of the inhibitors had potent activity against P. falciparum isolates circulating recently in Uganda. A small number of genetic polymorphisms were identified in the proteasome subunits of the Ugandan isolates. The S214F mutation in the β2 subunit was associated with decreased susceptibility to peptide boronates, but not other tested classes of proteasome inhibitors, although the infrequency of this mutation limited the analysis. Overall, a number of proteasome inhibitors offered potent activity against P. falciparum circulating in Uganda, and genetic variation in the β2 and β5 subunit targets was uncommon.

The 7 tested proteasome inhibitors mostly showed potent ex vivo activity, with values similar to those previously seen against cultured P. falciparum laboratory strains for asparagine ethylenediamine (12, 21), macrocyclic peptide, and peptide boronate inhibitors (21, 22). Asparagine ethylenediamines and macrocyclic peptides had median IC50s <50 nM against the Ugandan isolates, suggesting potential as antimalarial lead compounds. Peptide boronates had varied activity, with median IC50 values of 56 to 668 nM against the Ugandan isolates. Among the isolates studied, strong correlations were seen between results for chemically related inhibitors, suggesting shared determinants of activity.

Previous studies showed selection for a number of polymorphisms in different proteasome subunits in P. falciparum laboratory strains incubated with proteasome inhibitors (10, 12, 15, 22). To assess genotype variability in circulating Ugandan isolates, we sequenced the β2 and β5 catalytic proteasome subunits, which are predicted inhibitor targets, and 5 regulatory subunits. We identified a small number of polymorphisms in the β2 and β5 subunits, and we searched for associations between these and other polymorphisms and ex vivo susceptibilities. The two identified mutations in the β2 subunit, S214F and I204T, were both found in isolates with mixed genotypes. Isolates with one of these mutations, β2 S214F, had decreased susceptibility to two peptide boronates, MMV1579506 and MMV1794229, but the small number of available mutant parasites limited the analysis. The S214F mutation is located in the C-terminal tail of the β2 subunit, which wraps around the β3 subunit (Fig. 3; [23]), but the basis of altered inhibitor sensitivity is unclear. Two identified mutations in the β5 subunit, A142S and D150E, were not associated with alterations in susceptibility to proteasome inhibitors. Two mutations in the RPN10 subunit and one mutation in PF3D7_0808300 were common, but these were not associated with altered susceptibility to tested compounds. No polymorphisms were seen in the 19S PfRPT4 subunit, the α-type-6, subunit, or the fourth exon of the β6 subunit, in which mutations have previously been selected by proteasome inhibitors in vitro (10, 12, 22).

To further study the relevance of the β2 214F mutation, which was identified in Ugandan isolates, we assessed susceptibilities of culture adapted Ugandan strains to multiple proteasome inhibitors. β2 214F mutant parasites had decreased susceptibility to MMV1579506 and MMV1794229 compared to that of W2 strain and laboratory-selected β2 49E mutant parasites, but there were no significant differences in susceptibilities between β2 S214F wild type and mutant Ugandan strains. There were no significant differences in susceptibilities to other tested inhibitors between β2 wild type and mutant parasites.

This study had important limitations. First, different proteasome inhibitors were available for ex vivo analysis for only limited time frames, limiting our sample size for key compounds. One class, the peptide vinyl sulfones, was not available until after evaluation of field isolates, and therefore was only studied against selected culture adapted clones. Second, only small numbers of isolates with mutations in the β2 or β5 subunit were identified, limiting our ability to characterize the impacts of these polymorphisms. Third, most mutant isolates had mixed wild type/mutant genotypes, as typical in a region with high multiplicity of infection, further limiting our ability to characterize impacts of mutations.

In summary, multiple ethylenediamine and peptide boronate proteasome inhibitors demonstrated potent activity against Ugandan P. falciparum isolates. Modest variations in activities were generally not explained by polymorphisms seen in the β2, β5, RPN10, and PF3D7_0808300 subunits, although the β2 S214F mutation was associated with decreased ex vivo activity of two inhibitors in the few isolates with this mutation. Importantly, resistance-mediating mutations previously selected in vitro were not seen in Ugandan isolates. Overall, our results add confidence that, although studied proteasome inhibitors can select for resistance in vitro, they are likely to show consistently strong activity against P. falciparum isolates now circulating in East Africa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

Between July 2017 and August 2020, subjects over 6 months of age presenting at the outpatient clinics of Tororo District Hospital, Tororo District or Masafu General Hospital, Busiu District diagnosed with uncomplicated falciparum malaria, confirmed by Giemsa-stained blood films, were enrolled after providing informed consent, as previously described (24). Blood was collected in heparinized tubes and spotted onto filter paper before treatment with artemether-lumefantrine, following national guidelines. The study was approved by the Makerere University Research and Ethics Committee, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research.

Sources of proteasome inhibitors.

TDI4258 (12, 21, 22), TDI8304 (12, 21, 22), TDI8239 (25), WZ32 (12, 21, 22) and MMV1794229 (19) were synthesized as previously reported. MMV1579506 and MMV1581599 were synthesized by Takeda Pharmaceuticals and provided by Medicines for Malaria Venture. WLW-VS and WLL-VS were synthesized as previously described (17) and kindly provided by Matthew Bogyo, Stanford University.

Ex vivo and in vitro drug susceptibilities.

Compounds were prepared as 10 mM stock solutions in dimethyl sulfoxide (except H2O or 70% EtOH for chloroquine) and stored at −20°C. Working solutions were prepared within 24 h of susceptibility tests and stored at 4°C. Drug susceptibility assays utilized a 72 h SYBR green assay, as previously described (24). In brief, drugs were serially diluted 3-fold in complete media (RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 0.2% NaHCO3, 0.1 mM hypoxanthine, 25 μg/mL gentamicin, and 0.5% AlbuMAX II [Invitrogen]). For ex vivo studies, the concentration ranges of the compounds were 10 μM to 0.51 nM for TDI-8304, TDI-8239, MMV1794229, and MMV1579506; 50 μM to 25 nM for MMV1581599; and 1 μM to 0.05 nM for TDI-4258 and WZ32. For the in vitro studies, the concentration ranges of the compounds were 5 μM to 0.25 nM for chloroquine, WLL, and WLW and 10 μM to 0.51 nM for TDI-4258, TDI-8304, MMV1794229. Parasite cultures (including the control laboratory strain W2, obtained from the Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center) and drug-free or parasite-free controls were added to the 96-well assay plates to reach a parasitemia of 0.2% and hematocrit of 2%, plates were incubated for 72 h at 37°C, and parasite growth was then assessed based on SYBR green fluorescence. In vitro drug susceptibility assays consisted of three biological replicates with two technical replicates per assay. Relative fluorescence intensity, measured at 485 nm excitation and 530 nm emission, was plotted against log drug concentration to determine the IC50 for each compound. Data were curve fit with a variable slope function using Prism 8.4 (GraphPad Software).

Culture adaptation of Ugandan isolates.

Ugandan isolates were cultured for 2 to 3 weeks and, when robust growth was established, cryopreserved in 50% glycerolyte (Fenwal) solution and stored in liquid nitrogen. Subsequently, parasites were thawed using a stepwise process in 12% NaCl, 1.6% NaCl, and then 0.2% glucose/0.9% NaCl, and cultured in complete media at 2% hematocrit.

Characterization of P. falciparum genotypes.

P. falciparum DNA was extracted from dried blood spots using Chelex-100 (26). The β2 subunit (PF3D7_1328100) was amplified by PCR with primers β2_F1 (ATGAAACTCGAATATATAAATATACTC) and β2_R1 (GGTATAACTTATGCATCTTCTACAG). The β5 subunit (PF3D7_1011400) was amplified by PCR with primers β5_F1 (ATGGTAATAGCAAGTGATG) and β5_R1 (AACATATTGATCCTTTTGTTCAGGA). Part of the fourth exon of the β6 subunit (PF3D7_0518300) was amplified using a nested PCR with primers β6_F1 (CAGAGAAGGAAAATGTAATAGAGCATG) and β6_R1 (GTCTCTTTCAGTTGCTGAAGTAATAG) for round 1 and primers β6_F2 (ACTGTCATTGGCTTAACTGGT) and β6_R2 (GGAACCACTACCAACACAGGA) for round 2. Sequences of PCR products were determined using dideoxy sequencing (Eurofins Genomics), and sequences were analyzed with CodonCode Aligner (CodonCode Corporation) against the 3D7 reference genome. In addition, the β2 subunit sequences of 769 isolates, β5 subunit sequences of 785 isolates, 19S PfRPT4 subunit sequences of 893 isolates, alpha-type-6 subunit sequences of 893 isolates, RPN10 subunit sequences of 833 isolates, and PF3D7_0808300 sequences of 627 isolates were analyzed using MIP capture and deep sequencing, with library preparation and sequencing as previously reported (27). Subunit specific probes for this analysis were designed using MIPTools software (v.0.19.12.13; https://github.com/bailey-lab/MIPTools) (Table S1). The Miplicorn program (https://github.com/bailey-lab/miplicorn) was used to analyze raw sequencing data and call variants.

Construction of a model of the β2 subunit.

A model of the β2 subunit was constructed with PyMOL using the published structure of the Pf20S proteasome (PDB model number: 6MUV; P. falciparum 20S proteasome which includes the β2 subunit and two PA28 activators). The mutagenesis tool was used to visualize the mutations observed in the Ugandan isolates.

Statistical analysis.

The Spearman-rank test was used to assess correlations of results for individual isolates between compounds. The Wilcoxon test was used to assess associations between IC50s and genotypes. One-way ANOVA was used to detect overall differences in in vitro susceptibilities of Ugandan isolates and laboratory strains. Post hoc analysis was conducted using pairwise t-tests with Bonferroni correction to determine which matched pairs were significantly different from one another. Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 8.4 and R v.3.4.4. All tests were two-tailed and considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Data availability.

Raw sequencing reads are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession number (PRJNA850445 and ON042495-ON042749, ON165416-ON165513, ON661874-ON661996). MIP probes and PCR primers used in this study are listed in Table S1. MIPWrangler (https://github.com/bailey-lab/MIPWrangler) and MIPTools (https://github.com/bailey-lab/MIPTools) software is available on GitHub. All additional data are available on request from the authors (philip.rosenthal@ucsf.edu).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from The National Institutes of Health (AI139179 to P.J.R., AI075045 to P.J.R., AI143714 to G.L., T37MD003407 to U. California, Berkeley) and the Medicines for Malaria Venture (RD-15-0001 to P.J.R.). We thank study participants and staff members of the clinics where samples were collected. We also thank Matthew Bogyo, Stanford University for generously providing compounds for study and Barbara Stokes and David Fidock, Columbia University, for providing the V1/S K13C580Y strain with the β2 49E mutation.

S.G., O.K., S.C., P.K.T., O.B., M.O., S.O., T.K., and R.A.C. assisted in study design, performed ex vivo IC50 assays, and archived data. M.D. and J.L. provided project administrative and logistical support. S.G., O.K., M.D.C., O.A., and J.A.B. performed and analyzed genotyping studies. G.L. assisted in generating the protein model. S.G., O.K., R.A.C., and B.R.B. verified and analyzed data and performed statistical analysis. R.A.C., S.L.N., L.A.K., G.L., and P.J.R. provided guidance in study design and intellectual support. S.G., O.K., and P.J.R. wrote the draft of the manuscript and all authors corrected and approved the final manuscript.

M.D. is employed by Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV), who cofunded this study.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2021. World malaria report 2021. World Health Organization, Geneva. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/350147. Retrieved 4 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka K. 2009. The proteasome: overview of structure and functions. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 85:12–36. 10.2183/pjab.85.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J, Fang Y, Fan RA, Kirk CJ. 2021. Proteasome inhibitors and their pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and metabolism. Int J Mol Sci 22:11595. 10.3390/ijms222111595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang H, Lin G. 2021. Microbial proteasomes as drug targets. PLoS Pathog 17:e1010058. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HM, Yu Y, Cheng Y. 2011. Structure characterization of the 26S proteasome. Biochim Biophys Acta 1809:67–79. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orlowski M, Wilk S. 2000. Catalytic activities of the 20S proteasome, a multicatalytic proteinase complex. Arch Biochem Biophys 383:1–16. 10.1006/abbi.2000.2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budenholzer L, Cheng CL, Li Y, Hochstrasser M. 2017. Proteasome structure and assembly. J Mol Biol 429:3500–3524. 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deveraux Q, Ustrell V, Pickart C, Rechsteiner M. 1994. A 26S protease subunit that binds ubiquitin conjugates. J Biol Chem 269:7059–7061. 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)37244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Plasmodium Genome Database Collaborative. 2001. PlasmoDB: an integrative database of the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Tools for accessing and analyzing finished and unfinished sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res 29:66–69. 10.1093/nar/29.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stokes BH, Yoo E, Murithi JM, Luth MR, Afanasyev P, da Fonseca PCA, Winzeler EA, Ng CL, Bogyo M, Fidock DA. 2019. Covalent Plasmodium falciparum-selective proteasome inhibitors exhibit a low propensity for generating resistance in vitro and synergize with multiple antimalarial agents. PLoS Pathog 15:e1007722. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aminake MN, Arndt H-D, Pradel G. 2012. The proteasome of malaria parasites: a multi-stage drug target for chemotherapeutic intervention? Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2:1–10. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkman LA, Zhan W, Visone J, Dziedziech A, Singh PK, Fan H, Tong X, Bruzual I, Hara R, Kawasaki M, Imaeda T, Okamoto R, Sato K, Michino M, Alvaro EF, Guiang LF, Sanz L, Mota DJ, Govindasamy K, Wang R, Ling Y, Tumwebaze PK, Sukenick G, Shi L, Vendome J, Bhanot P, Rosenthal PJ, Aso K, Foley MA, Cooper RA, Kafsack B, Doggett JS, Nathan CF, Lin G. 2018. Antimalarial proteasome inhibitor reveals collateral sensitivity from intersubunit interactions and fitness cost of resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:E6863–E6870. 10.1073/pnas.1806109115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, Tsu C, Blackburn C, Li G, Hales P, Dick L, Bogyo M. 2014. Identification of potent and selective non-covalent inhibitors of the Plasmodium falciparum proteasome. J Am Chem Soc 136:13562–13565. 10.1021/ja507692y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindenthal C, Weich N, Chia Y-S, Heussler V, Klinkert M-Q. 2005. The proteasome inhibitor MLN-273 blocks exoerythrocytic and erythrocytic development of Plasmodium parasites. Parasitology 131:37–44. 10.1017/s003118200500747x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie SC, Gillett DL, Spillman NJ, Tsu C, Luth MR, Ottilie S, Duffy S, Gould AE, Hales P, Seager BA, Charron CL, Bruzzese F, Yang X, Zhao X, Huang S-C, Hutton CA, Burrows JN, Winzeler EA, Avery VM, Dick LR, Tilley L. 2018. Target validation and identification of novel boronate inhibitors of the Plasmodium falciparum proteasome. J Med Chem 61:10053–10066. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, van der Linden WA, Verdoes M, Florea BI, McAllister FE, Govindaswamy K, Elias JE, Bhanot P, Overkleeft HS, Bogyo M. 2014. Assessing subunit dependency of the Plasmodium proteasome using small molecule inhibitors and active site probes. ACS Chem Biol 9:1869–1876. 10.1021/cb5001263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, O'Donoghue AJ, van der Linden WA, Xie SC, Yoo E, Foe IT, Tilley L, Craik CS, da Fonseca PCA, Bogyo M. 2016. Structure- and function-based design of Plasmodium-selective proteasome inhibitors. Nature 530:233–236. 10.1038/nature16936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaMonte GM, Almaliti J, Bibo-Verdugo B, Keller L, Zou BY, Yang J, Antonova-Koch Y, Orjuela-Sanchez P, Boyle CA, Vigil E, Wang L, Goldgof GM, Gerwick L, O'Donoghue AJ, Winzeler EA, Gerwick WH, Ottilie S. 2017. Development of a potent inhibitor of the Plasmodium proteasome with reduced mammalian toxicity. J Med Chem 60:6721–6732. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie SC, Metcalfe RD, Mizutani H, Puhalovich T, Hanssen E, Morton CJ, Du Y, Dogovski C, Huang S-C, Ciavarri J, Hales P, Griffin RJ, Cohen LH, Chuang B-C, Wittlin S, Deni I, Yeo T, Ward KE, Barry DC, Liu B, Gillett DL, Crespo-Fernandez BF, Ottilie S, Mittal N, Churchyard A, Ferguson D, Aguiar ACC, Guido RVC, Baum J, Hanson KK, Winzeler EA, Gamo F-J, Fidock DA, Baud D, Parker MW, Brand S, Dick LR, Griffin MDW, Gould AE, Tilley L. 2021. Design of proteasome inhibitors with oral efficacy in vivo against Plasmodium falciparum and selectivity over the human proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118:e2107213118. 10.1073/pnas.2107213118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoo E, Stokes BH, de Jong H, Vanaerschot M, Kumar T, Lawrence N, Njoroge M, Garcia A, Van der Westhuyzen R, Momper JD, Ng CL, Fidock DA, Bogyo M. 2018. Defining the determinants of specificity of Plasmodium proteasome inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc 140:11424–11437. 10.1021/jacs.8b06656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhan W, Zhang H, Ginn J, Leung A, Liu YJ, Michino M, Toita A, Okamoto R, Wong T, Imaeda T, Hara R, Yukawa T, Chelebieva S, Tumwebaze PK, Lafuente-Monasterio MJ, Martinez MS, Vendome J, Beuming T, Sato K, Aso K, Rosenthal PJ, Cooper RA, Meinke PT, Nathan CF, Kirkman LA, Lin G. 2021. Development of a highly selective Plasmodium falciparum proteasome inhibitor with anti-malaria activity in humanized mice. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 60:9279–9283. 10.1002/anie.202015845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhan W, Visone J, Ouellette T, Harris JC, Wang R, Zhang H, Singh PK, Ginn J, Sukenick G, Wong T-T, Okoro JI, Scales RM, Tumwebaze PK, Rosenthal PJ, Kafsack BFC, Cooper RA, Meinke PT, Kirkman LA, Lin G. 2019. Improvement of asparagine ethylenediamines as anti-malarial Plasmodium -selective proteasome inhibitors. J Med Chem 62:6137–6145. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramos PC, Marques AJ, London MK, Dohmen RJ. 2004. Role of c-terminal extensions of subunits β2 and β7 in assembly and activity of eukaryotic proteasomes. J Biol Chem 279:14323–14330. 10.1074/jbc.M308757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tumwebaze PK, Katairo T, Okitwi M, Byaruhanga O, Orena S, Asua V, Duvalsaint M, Legac J, Chelebieva S, Ceja FG, Rasmussen SA, Conrad MD, Nsobya SL, Aydemir O, Bailey JA, Bayles BR, Rosenthal PJ, Cooper RA. 2021. Drug susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum in eastern Uganda: a longitudinal phenotypic and genotypic study. Lancet Microbe 2:e441–e449. 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00085-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Hsu H-C, Kahne SC, Hara R, Zhan W, Jiang X, Burns-Huang K, Ouellette T, Imaeda T, Okamoto R, Kawasaki M, Michino M, Wong T-T, Toita A, Yukawa T, Moraca F, Vendome J, Saha P, Sato K, Aso K, Ginn J, Meinke PT, Foley M, Nathan CF, Darwin KH, Li H, Lin G. 2021. Macrocyclic peptides that selectively inhibit the Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteasome. J Med Chem 64:6262–6272. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plowe CV, Djimde A, Bouare M, Doumbo O, Wellems TE. 1995. Pyrimethamine and proguanil resistance-conferring mutations in Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase: polymerase chain reaction methods for surveillance in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 52:565–568. 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.52.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aydemir O, Janko M, Hathaway NJ, Verity R, Mwandagalirwa MK, Tshefu AK, Tessema SK, Marsh PW, Tran A, Reimonn T, Ghani AC, Ghansah A, Juliano JJ, Greenhouse BR, Emch M, Meshnick SR, Bailey JA. 2018. Drug-resistance and population structure of Plasmodium falciparum across the Democratic Republic of Congo using high-throughput molecular inversion probes. J Infect Dis 218:946–955. 10.1093/infdis/jiy223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download aac.00817-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.2 MB (184.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Raw sequencing reads are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession number (PRJNA850445 and ON042495-ON042749, ON165416-ON165513, ON661874-ON661996). MIP probes and PCR primers used in this study are listed in Table S1. MIPWrangler (https://github.com/bailey-lab/MIPWrangler) and MIPTools (https://github.com/bailey-lab/MIPTools) software is available on GitHub. All additional data are available on request from the authors (philip.rosenthal@ucsf.edu).