Abstract

Salivary anticandidal activities play an important role in oral candidal infection. R. P. Santarpia et al. (Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 7:38–43, 1992) developed in vitro anticandidal assays to measure the ability of saliva to inhibit the viability of Candida albicans blastoconidia and the formation of germ tubes by C. albicans. In this report, we describe modifications of these assays for use with small volumes of saliva (50 to 100 μl). For healthy subjects, there is strong inhibition of blastoconidial viability in stimulated parotid (75%), submandibular-sublingual (74%), and whole (97%) saliva, as well as strong inhibition of germ tube formation (>80%) for all three saliva types. The susceptibility of several Candida isolates to inhibition of viability by saliva collected from healthy subjects is independent of body source of Candida isolation (blood, oral cavity, or vagina) or the susceptibility of the isolate to the antifungal drug fluconazole. Salivary anticandidal activities in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients were significantly lower than those in healthy controls for inhibition of blastoconidial viability (P < 0.05) and germ tube formation (P < 0.001). Stimulated whole-saliva flow rates were also significantly lower (P < 0.05) for HIV-infected patients. These results show that saliva of healthy individuals has anticandidal activity and that this activity is reduced in the saliva of HIV-infected patients. These findings may help explain the greater incidence of oral candidal infections for individuals with AIDS.

Saliva contains many antifungal proteins, e.g., histatins (16), lysozyme (6, 13, 24), lactoferrin (8, 11), and secretory immunoglobulin A. Several studies have demonstrated associations between oral candidal status and concentrations of salivary histatins (1, 5) or lysozyme (25). Methods to directly evaluate anticandidal activities of saliva have been reported previously (21). These assays are based on the ability of saliva to inhibit blastoconidial viability of Candida albicans or to inhibit the formation of germ tubes by C. albicans. Typically, C. albicans organisms grow as single ellipsoidal cells called blastoconidia. In the presence of inducing environmental signals, e.g., alterations of pH, temperature, and nutrients, C. albicans can assume a hyphal and/or pseudohyphal form (3). Germ tube formation is the first step in the conversion of blastoconidia to hyphal form. Human saliva from healthy individuals will inhibit C. albicans blastoconidial viability and will inhibit the formation of germ tubes by C. albicans (21). Previous reports show that salivary anticandidal activities are severely compromised in AIDS patients (18).

Assays of salivary antifungal capacities are useful for investigation of the pathogenesis of oral candidal infections. However, such investigations are limited, perhaps because the current methods require a minimum of 1 ml of saliva for a single assay. In cases of hyposalivation or xerostomia, a common occurrence for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-AIDS patients (21, 25), the ability to obtain 1 ml of saliva can be difficult. In the present study, we have modified existing anticandidal assays for use with smaller quantities of saliva and we have optimized the assay conditions for these modified methods. We have used these assays to characterize salivary anticandidal activities against several strains of Candida isolated from different body sites. We also used these assays against Candida strains which were either resistant or susceptible to the antifungal drug fluconazole. Finally, we used these assays to characterize the anticandidal activities of stimulated whole saliva obtained from a cohort of HIV-AIDS patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

To develop and characterize the microanticandidal assays, multiple stimulated whole- and glandular saliva samples were collected from four medically healthy male volunteers. The mean age was 41 years with a range from 26 to 52 years. These volunteers took no medications.

These anticandidal microassays were used to characterize the anticandidal activity of the saliva of HIV-AIDS patients (n = 12 males; 39 ± 6.7 years) who were recruited from participants in the Fluconazole Efficacy Study (T. F. Patterson, Department of Medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio). The mean CD4+ lymphocyte count was 162.4 ± 165.0 cells/μl (mean ± standard deviation [SD]). All patients were taking anti-HIV and/or anti-AIDS medications including lamivudine, stavudine, zudovudine, didanosine (ddI), delavirdine, nevirapine, indinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, or saquinavir. No patient took fluconazole or other anticandidal medications at the time of saliva collection. Stimulated whole-saliva samples collected from 17 male healthy volunteers (23 to 53 years old with a mean of 31 years) were used as controls for the studies with the HIV-AIDS patients.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and the Audie L. Murphy Division, South Texas Veterans Health Care System. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Saliva collection and treatment.

Stimulated whole saliva was obtained by having subjects chew paraffin wax. Stimulated parotid saliva was obtained by using a modified Carlson-Crittenden cup placed over Stenson’s duct and held in place with gentle suction (23). Submandibular-sublingual saliva was collected with gentle suction by using a plastic micropipette (4) held at the orifices of Wharton’s and Bartholin’s ducts in the floor of the mouth (26). For stimulation of glandular saliva, the dorsolateral surfaces of the tongue were swabbed with a 2% citric acid solution at intervals of 30 s. The saliva collection time was 5 min. The collected saliva was immediately placed on ice. All saliva samples were adjusted to pH 4.5 with glacial acetic acid. For whole-saliva samples, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) was added to prevent proteolysis. The acidified saliva was boiled for either 2.5 (parotid and submandibular-sublingual saliva) or 10 (whole saliva) min. After cooling on ice for 20 min, the samples were centrifuged (16,000 × g, IEC CentraMP4R centrifuge, rotor 851, 4°C) for 30 min. These treatments effectively removed all endogenous Candida organisms from all types of saliva. The supernatant was either used immediately for antifungal assays or stored at −70°C.

Saliva pool for assay control.

Stimulated whole saliva was collected from several healthy donors, and the salivas were combined. This saliva pool was processed as described above, and the supernatant was stored in small aliquots at −70°C. When patient and healthy control samples were evaluated, a sample of this pool was included on each day to ensure assay reproducibility. If the percent inhibition for this assay control pool was less than 90%, the saliva samples were evaluated again on another day.

Assay of salivary inhibition of blastoconidial viability.

The C. albicans isolates used in this project were isolated from HIV-AIDS patients. These isolates were from different body sites and had different susceptibilities to the anticandidal drug fluconazole. An isolate was considered fluconazole sensitive when the MIC of fluconazole was ≤8 μg/ml. The MICs for the two fluconazole-resistant isolates (2520 and 566) were ≥64 μg/ml.

The microassay of salivary inhibition of blastoconidial viability was performed by modifications of the method of Pollock et al. (18). C. albicans organisms were grown to late log phase (optical density of 1.4 to 1.6 at 600 nm). After centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C and washing with sterilized water, the Candida suspension was adjusted to 3 × 106 CFU/ml with 25 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5). The incubation mixture contained 5 μl of Candida suspension and either 95 μl of saliva or 95 μl of 25 mM sodium acetate buffer (control). The incubation time for this mixture was 1 h at 37°C for stimulated parotid or submandibular-sublingual saliva and 4 h for whole saliva. After this incubation, the mixture was diluted 100-fold with 25 mM MES [2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid] buffer (pH 6). The diluted mixture was then further incubated at 37°C for 4 h (glandular saliva samples) or 3 h (whole-saliva samples). After this second incubation, 100 μl was inoculated onto a Sabouraud dextrose agar plate containing chloramphenicol (0.01%). The CFU were counted after 24 h of incubation at 37°C. The percent inhibition of blastoconidial viability for each sample was calculated in comparison with the control (containing no saliva) according to the following formula: [1 − (CFU in saliva/CFU in buffer control)] × 100. Duplicate determinations were done for each sample. All patient and healthy control salivary assays included a pooled saliva sample (described above) as an assay control.

Assay of salivary inhibition of germ tube formation.

The salivary germ tube inhibition microassay was performed by modifications of the method described by Santarpia et al. (21). Late-log-phase C. albicans (optical density per milliliter of 1.4 to 1.6 at 600 nm) or a static colony (diluted to 3 × 107 CFU/ml in water) was used. The assay mixture for parotid and submandibular-sublingual saliva contained 6.5 μl of 27.2 mg of filter-sterilized N-acetylglucosamine per ml, 15 μl of fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 μl of the freshly prepared Candida suspension, and either 50 μl of saliva or 50 μl of 20 mM acetate buffer (control). In order to obtain optimal conditions for germ tube formation in the whole-saliva assay system, 32.5 μl of FBS was required. After incubation for 3 h at 37°C, the mixture was sonicated for 15 min. An aliquot of the mixture was examined under an Olympus microscope (magnification, ×400). A total of 300 blastoconidia and germ tubes were counted, and the percent inhibition of blastoconidial germination was calculated according to the following formula: [1 − (% germ tubes in saliva/% germ tubes in buffer control)] × 100.

Statistical analysis.

The data in the text is given as the mean ± 1 SD or as the median and the 25th to 75th percentile. Analysis of variance was used to study the differences in susceptibility of different Candida isolates to saliva inhibition. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the differences in salivary anticandidal activities and flow rates between the HIV-positive cohort and the healthy group.

RESULTS

Anticandidal activities could be demonstrated with small quantities (50 to 100 μl) of saliva. Two oral C. albicans isolates from AIDS patients (1215 and 566) were used during the characterization of salivary anticandidal assays. Since the results with the two strains were similar, only the results for saliva against isolate 1215 are presented in Table 1. The data shown in Table 1 is the result of multiple saliva samples taken at different times from a single healthy volunteer. All saliva samples, i.e., parotid, submandibular-sublingual, and whole saliva, had strong inhibition of both C. albicans blastoconidial viability and germ tube formation. Similar anticandidal activities were observed for three other healthy subjects (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Anticandidal activities in whole and glandular saliva collected from a single healthy subjecta

| Type of saliva | Blastoconidial viability

|

Germ tube

formation

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Buffer control (CFU/plate) | Saliva treatment (CFU/plate) | % Inhibitionb | n | Buffer control (% germination) | Saliva treatment (% germination) | % Inhibitionc | |

| WS | 5 | 185.3 ± 25.9 | 5.5 ± 2.8 | 97.0 ± 1.6 | 3 | 94.4 ± 6.7 | 14.2 ± 11.1 | 85.3 ± 10.7 |

| PS | 4 | 175.3 ± 50.8 | 47.0 ± 19.7 | 74.7 ± 7.4 | 3 | 58.3 ± 16.7 | 0 | 100 |

| SS | 4 | 166.8 ± 44.9 | 47.5 ± 22.8 | 74.1 ± 10.6 | 5 | 63.6 ± 8.2 | 0 | 100 |

Candida isolate 1215 was used. Values, except for n (number of independent measurements), are shown as means ± SDs. WS, whole saliva; PS, parotid saliva; SS, submandibular-sublingual saliva.

Calculated as follows: [1 − (CFU in saliva/CFU in buffer control)] × 100.

Calculated as follows: [1 − (% germ tubes in saliva/% germ tubes in buffer control)] × 100.

The inhibition of blastoconidial viability against a variety of C. albicans isolates was examined in stimulated whole, parotid, and submandibular-sublingual saliva. The data is shown in Table 2. In these assays, whole and submandibular-sublingual saliva were from a single donor while the parotid saliva studies used saliva from two individuals. Since the methods to analyze anticandidal activities in individual glandular and whole saliva were slightly different, a comparison of anticandidal activities among whole saliva, parotid saliva, and submandibular-sublingual saliva was not performed. There were significant differences among the saliva types in the susceptibilities of different Candida isolates to inhibition of blastoconidial viability (P < 0.001 for each saliva type). In order to see if salivary inhibition of blastoconidial viability was related to fluconazole sensitivity, strains of fluconazole-sensitive and -resistant Candida were included. Strong salivary inhibition of blastoconidial viability was detected for all Candida isolates, regardless of fluconazole sensitivity or resistance. The range of salivary inhibition of blastoconidial viability was 98.5 to 55.3% for whole saliva, 97.9 to 68.3% for parotid saliva, and 91.3 to 21.3% for submandibular-sublingual saliva. This data suggests that the susceptibilities of different candidal isolates to inhibition of blastoconidial viability by saliva might be independent of body site of isolation and the susceptibility of the Candida strain to fluconazole. The salivary inhibition of blastoconidial viability against isolates from blood (593) and vagina (2520, 456, and 3741) was comparable to that for isolates from the oral cavity (566, 1215, and 969). Two isolates (540, an oral isolate, and 546, isolated from blood) appeared to be more resistant to salivary inhibition of blastoconidial viability. Both isolates were susceptible to fluconazole, an antifungal drug. Our preliminary studies also suggest that there was no apparent difference in salivary inhibition of blastoconidial viability between Candida organisms isolated from AIDS patients (1215 and 566) and those from patients with denture stomatitis (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Salivary inhibition of blastoconidial viability with different Candida isolatesa

| Isolate no. and descriptionb | % Inhibition of

viabilityc

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| WS (n = 5) | PS (n = 4) | SS (n = 4) | |

| 2520, VR | 91.4 ± 1.1 | 76.1 ± 1.2 | 53.1 ± 2.6 |

| 456, VS | 94.6 ± 1.1 | 95.6 ± 1.4 | 91.3 ± 1.6 |

| 540, OS | 65.5 ± 1.8 | 68.3 ± 1.6 | 21.3 ± 2.4 |

| 566, OR | 84.6 ± 1.6 | 97.9 ± 0.6 | 88.8 ± 1.8 |

| 546, BS | 61.2 ± 1.6 | 68.7 ± 1.4 | 49.9 ± 1.6 |

| 539, AS | 90.0 ± 1.1 | 77.0 ± 1.0 | 47.9 ± 1.8 |

| 1215, OS | 97.4 ± 0.9 | 75.0 ± 0.8 | 62.2 ± 0.8 |

| 996, OS | 98.5 ± 0.9 | 74.5 ± 2.4 | 95.7d |

| 3741, VS | NDe | 85.4 ± 1.0 | 77.7d |

The saliva used in these studies was obtained from healthy donors. Each value is mean ± SD.

V, vagina; O, oral; B, blood; A, aorta; R, fluconazole resistant (MIC > 64 μg/ml); S, fluconazole sensitive (MIC < 8 μg/ml).

WS, whole saliva; PS, parotid saliva; SS, submandibular-sublingual saliva; n, number of determinations.

Single determination.

ND, not determined.

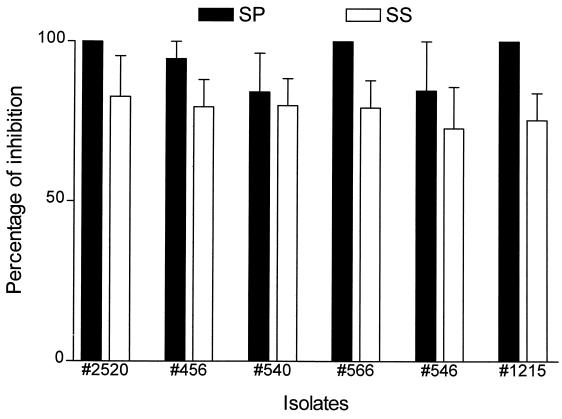

Germ tube formation of all tested Candida isolates was also inhibited by whole, parotid, and submandibular-sublingual saliva. The susceptibilities of six candidal isolates to inhibition of germ tube formation by parotid saliva (>86.3%) and submandibular-sublingual saliva (73 to 95%) are shown in Fig. 1. Again, this data suggests that there were no differences specifically related to isolation site or to fluconazole susceptibility.

FIG. 1.

Salivary inhibition of germ tube formation with different Candida isolates. The saliva of a healthy person was used. The height of the column indicates the mean percentage of inhibition with the SD being indicated by the error bars. The mean is based on three separate determinations. Closed columns indicate stimulated parotid saliva (SP), while open columns indicate stimulated submandibular-sublingual saliva (SS).

Anticandidal activities in paraffin-chewing-stimulated whole saliva of 12 HIV-infected patients and 17 healthy controls were evaluated by these anticandidal assay methods. The HIV-infected individuals had significantly lower (∼40%) median salivary flow rates than those of healthy controls (P < 0.05, Table 3). Isolates 1215 and 540 were used to study salivary inhibition of blastoconidial viability, whereas isolates 1215 and 566 were used to study salivary inhibition of germ tube formation. Almost all saliva samples from the healthy controls had 100% inhibition of both blastoconidial viability and germ tube formation. The median inhibition of blastoconidial viability by saliva from HIV-positive patients was significantly lower than that of the controls (P < 0.05, Table 3). The median salivary inhibition of Candida germ tube formation was also significantly reduced in HIV-positive patients compared to that for controls (P < 0.001, Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of anticandidal activities for whole saliva from HIV-positive patients and healthy controlsa

| Subject group (n) | Salivary flow rate (ml/min) | % Inhibition

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Blastoconidial viability | Germ tube formation | ||

| HIV positive (12) | 1.21 (0.64–1.35)b | 88.8 (70.4–95.2)c | 80.3 (11.1–87.7)b |

| Control (17) | 2.00 (1.48–2.40) | 100 (97.9–100) | 100 (100–100) |

Each value is the median with the 25th and 75th percentiles indicated in parentheses.

Significantly different from the control (P < 0.001).

Significantly different from the control (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have modified published salivary anticandidal assays (21) for use with smaller quantities of saliva, and we have further characterized these assays. Using these in vitro bioassays, we have demonstrated that stimulated whole, parotid, and submandibular-sublingual saliva have strong anticandidal activities, i.e., inhibition of blastoconidial viability and inhibition of germ tube formation. Saliva appears to have a very broad spectrum of anticandidal activities. Although the susceptibilities of Candida isolates to saliva may be varied, the relative susceptibility or resistance of different C. albicans isolates to saliva was not related to the body site of isolation or to fluconazole resistance or susceptibility (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Although saliva contains many antifungal proteins, it also contains the nutrients for Candida growth (5, 17). Therefore, salivary inhibition of blastoconidial viability in vitro can be detected only indirectly. The assay for inhibition of blastoconidial viability is based on damage of the C. albicans cell membrane by preincubation in saliva followed by incubation in a nonnutrient buffer leading to the inability of the organism to grow (21). As indicated in the previous report (21), the assay for inhibition of blastoconidial viability was sensitive to pH, saliva preincubation time, boiling time, and yeast cell concentration. We found that the saliva sample could be stored at a low temperature and successfully used for the anticandidal assays if the saliva had been acidified and boiled before freezing. If the saliva samples were frozen before being acidified and boiled, about 40% of the activity for inhibition of blastoconidial viability was lost (data not shown). Studies have also suggested that germinated Candida organisms are less susceptible to killing by other salivary anticandidal proteins, i.e., histatins (24). We have tested the salivary inhibitory activities toward germinated Candida and blastoconidia by using glandular saliva. There was no difference in salivary inhibition of Candida blastoconidial viability between these two forms (data not shown).

In our assay, a relatively high yeast-to-saliva ratio was used, which should increase the possible detection of mild alterations in salivary inhibition of blastoconidial viability. The protease inhibitor, PMSF, was not needed in the previous report, for which a larger quantity of saliva was used in the assay (21). However, in our study, the addition of the protease inhibitor PMSF was critical to preserve the inhibition of blastoconidial viability for treated whole saliva. However, it is possible that PMSF could have a negative effect on germ tube formation. Previous studies have shown that germ tube formation is dependent on the concentrations of serum (3a). We found that the concentration of FBS in the incubation mixture had to be almost doubled (increased from 18% in the non-PMSF-treated glandular saliva samples to 33% in the PMSF-treated whole-saliva samples) for germ tube formation to occur at a low level in the saliva-treated sample. By increasing the FBS concentration for the whole-saliva samples so that a low level of germ tube formation occurred in saliva from healthy people, we believe we have overcome any negative effect of PMSF on germ tube formation.

It has been suggested that the hyphal form of Candida is more virulent than the blastoconidial form in vivo. Formation of hyphae appears to enhance the adhesion of Candida to host epithelial cells and also to enhance tissue invasion (7, 20). In vitro, saliva inhibition of germ tube formation is dependent on the concentrations of FBS and yeast cells as well as pH (2, 21). In our assay system, 18 and 33% FBS were found to be the optimal concentrations for glandular saliva and whole saliva, respectively. Unlike the previous report, which used water for the control in the germ tube formation assays (21), we used a sodium acetate buffer (25 mM, pH 4.5) as the control germination mixture, since saliva samples were acidified to 4.5 with acetic acid immediately after collection. We found that germ tube formation with use of acetate buffer for the control was reduced (approximately 20%; data not shown) compared to that with use of water.

Oral candidal infection is a common oral manifestation in HIV-infected patients (9, 14). HIV-positive patients usually have lower salivary flow rates, as demonstrated in our study. Most of our HIV-infected cohort were taking multiple anti-HIV drugs as well as drugs for management of HIV infection. Many of these are known to cause mouth dryness. A small proportion of the HIV-positive subjects may develop Sjögren’s-like syndrome during the course of HIV infection (22). Several studies have demonstrated a relationship between the occurrence of oral candidiasis and a decreased salivary flow rate (12, 14). In our current study, we have used our anticandidal microassays to demonstrate that the salivary anticandidal activities of whole saliva are compromised in HIV-positive patients. These results confirm observations of a previous study (18) which demonstrated that stimulated whole, parotid, and submandibular-sublingual saliva from AIDS patients had decreased salivary anticandidal activities (12). Both the inhibition of blastoconidial viability and the inhibition of germ tube formation in whole saliva were reduced in our HIV-positive patients. Reductions of concentrations or activities of salivary antifungal proteins, such as histatins and secretory immunoglobulin A, may account for the loss of anticandidal activities in HIV-positive patients (10, 15, 19). Current investigations in our laboratory are studying whether salivary antifungal components are altered in these HIV-positive patients and whether there is a relationship between salivary anticandidal activities and the progression of HIV infection.

In conclusion, we have modified salivary anticandidal assays for use with small volumes of saliva. The requirement for smaller volumes of saliva enables the study of salivary anticandidal activities in subjects with very low flow rates. We have found that human saliva has strong anticandidal activities and that there is a decrease in the salivary anticandidal activities in severely immunocompromised patients. This loss of salivary anticandidal activity in AIDS patients merits further elucidation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants DE-12188 (to C.-K.Y.) and DE-11381 (to T.F.P.) from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

We also acknowledge the contributions of Jose L. Lopez-Ribot and Marta Caceres.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkinson J C, Yeh C-K, Oppenheim F G, Bermudez D, Baum B J, Fox P C. Evaluation of salivary antimicrobial proteins following HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3:41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brant E C, Santarpia III R P, Pollock J J. The role of pH in salivary histidine-rich polypeptide antifungal germ tube inhibitory activity. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1990;5:336–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1990.tb00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buffo J, Herman M A, Soll D R. A characterization of pH-regulated dimorphism in Candida albicans. Mycopathologia. 1984;85:21–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00436698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Dabrowa N, Landau J W, Newcomer V D. The antifungal activity of physiologic saline in serum. J Invest Dermatol. 1965;45:368–377. doi: 10.1038/jid.1965.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox P C. Saliva composition and its importance in dental health. Compend Contin Educ Dent Suppl. 1989;13:S457–S460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jainkittivong A, Johnson D A, Yeh C-K. The relationship of salivary histatin levels and oral Candida carriage. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1998;13:181–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1998.tb00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamaya T. Lytic action of lysozyme on Candida albicans. Mycopathol Mycol Appl. 1970;42:197–207. doi: 10.1007/BF02051947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura L H, Pearsall N N. Relationship between germination of Candida albicans and increased adherence to human buccal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1980;28:464–468. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.2.464-468.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkpatrick C H, Green I, Rich R R, Schade A L. Inhibition of growth of Candida albicans by iron-unsaturated lactoferrin: relation to host-defense mechanisms in chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 1971;124:539–544. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.6.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein R S, Harris C A, Small C B, Moll B, Lesser M, Friedland G H. Oral candidiasis in high-risk patients as the initial manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:354–358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408093110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lal K, Pollock J J, Santarpia III R P, Heller H M, Kaufman H W, Fuhrer J, Steigbigel R T. Pilot study comparing the salivary cationic protein concentrations in healthy adults and AIDS patients: correlation with antifungal activity. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:904–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenander-Lumikari M, Johansson I. Effect of saliva composition on growth of Candida albicans and Torulopsis glabrata. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1995;10:233–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1995.tb00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandel I D, Barr C E, Turgeon E. Longitudinal study of parotid saliva in HIV-1 infection. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:209–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marquis G, Montplaisir S, Garzon S, Strykowski H, Auger P. Fungitoxicity of muramidase. Ultrastructural damage to Candida albicans. Lab Investig. 1982;46:627–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarthy G M, Mackie I D, Koval J, Sandhu H S, Daley T D. Factors associated with increased frequency of HIV-related oral candidiasis. J Oral Pathol Med. 1991;20:332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1991.tb00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller F, Froland S S, Hvatum M, Radl J, Brandtzaeg P. Both IgA subclasses are reduced in parotid saliva from patients with AIDS. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;83:203–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05615.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oppenheim F G, Xu T, McMillian F M, Levitz S M, Diamond R D, Offner G D, Troxler R F. Histatins, a novel family of histidine-rich proteins in human parotid secretion. Isolation, characterization, primary structure, and fungistatic effects on Candida albicans. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:7472–7477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollock J J, Denepitiya L, MacKay B J, Iacono V J. Fungistatic and fungicidal activity of human parotid salivary histidine-rich polypeptides on Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1984;44:702–707. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.3.702-707.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollock J J, Santarpia III R P, Heller H M, Xu L, Lal K, Fuhrer J, Kaufman H W, Steigbigel R T. Determination of salivary anticandidal activities in healthy adults and patients with AIDS: a pilot study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:610–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pontón J, Bikandi J, Moragues M D, Arilla M C, Elósegui R, Quindós G, Fisicaro P, Conti S, Polonelli L. Reactivity of Candida albicans germ tubes with salivary secretory IgA. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1979–1985. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750121001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryley J F, Ryley N G. Candida albicans—do mycelia matter? J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:225–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santarpia R P, III, Xu L, Lal K, Pollock J J. Salivary anti-candidal assays. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1992;7:38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1992.tb00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiodt M. HIV-associated salivary gland disease: a review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:164–167. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90189-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shannon I L, Prigmore J R, Chauncey H H. Modified Carlson-Crittenden device for the collection of parotid fluid. J Dent Res. 1962;41:778–783. doi: 10.1177/00220345620410040801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu T, Levitz S M, Diamond R D, Oppenheim F G. Anticandidal activity of major human salivary histatins. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2549–2554. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2549-2554.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeh C-K, Dodds M W J, Zuo P, Johnson D A. A population-based study of salivary lysozyme concentrations and candidal counts. Arch Oral Biol. 1997;42:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(96)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeh C-K, Fox P C, Ship J A, Busch K A, Bermudez D K, Wilder A-M, Katz R W, Wolff A, Tylenda C A, Atkinson J C, Baum B J. Oral defense mechanisms are impaired early in HIV-1 infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1988;1:361–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]