Abstract

Social connection is an understudied target of intervention for the health of individuals providing care for a family member with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD). To guide future research, we discuss considerations for interventions to promote social connection, with a particular focus on reducing loneliness: (a) include caregiver perspectives in designing and delivering interventions; (b) adapt to stages of dementia; (c) consider caregiving demands, including the use of brief interventions; (d) specify and measure mechanisms of action and principles of interventions; (e) consider dissemination and implementation at all stages of research. With support from the National Institute on Aging for a Roybal Center for Translational Research in the Behavioral and Social Sciences of Aging, we are developing a portfolio of mechanism-informed and principle-driven behavioral interventions to promote social connection in ADRD caregivers that can be flexibly applied to meet a diverse set of needs while maximizing resources and reducing demands on caregivers.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Behavior change, Interventions, Loneliness, Social isolation

Providing care for a family member with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD; hereafter ADRD caregivers) is a common experience, with over 20 million people in the United States providing unpaid care for a person with dementia each year (Chi et al., 2019). Providing such care can result in benefits, such as increased meaning and purpose, but is also associated with elevated levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms, accelerated aging-related cognitive decline, poor physical health, and reduced quality of life (Kovaleva et al., 2018; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021). In addition, experiences of social disconnection—including social isolation, a lack of social support, and feelings of loneliness—are common experiences among ADRD caregivers (Beeson, 2003; Parsons, 1997; Siriopoulos et al., 1999) with estimates indicating that up to 80% of caregivers will report feeling socially disconnected due to caregiving responsibilities (Carers UK, 2015). We suggest that social connection—that is, the quantity and quality of social ties that individuals have with other people (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017)—is a gravely understudied target of intervention to promote health and well-being for older adults in general, and ADRD caregivers in particular. While certain challenges associated with aging, including caring for a family member with dementia, may be difficult to change, social relationships remain malleable throughout life and may serve as an intervention target to promote coping, resilience, well-being, and health.

With support from the National Institute on Aging for a Roybal Center for Translational Research in the Behavioral and Social Sciences of Aging, The Rochester Roybal Center for Social Ties and Aging Research is developing a portfolio of mechanism-informed and principle-driven behavioral interventions (see Onken et al., 2014) to improve social relationships and reduce loneliness in ADRD caregivers. With funding from our center, investigators are developing, adapting, and testing brief behavioral interventions for their efficacy in improving social relationships and reducing loneliness while measuring mechanisms that account for improvements. In this article, we describe the rationale for our Center’s approach, as it may be useful for others interested in research and program development to address loneliness in later life and improving outcomes for ADRD caregivers.

The Importance of Social Connection for ADRD Caregivers

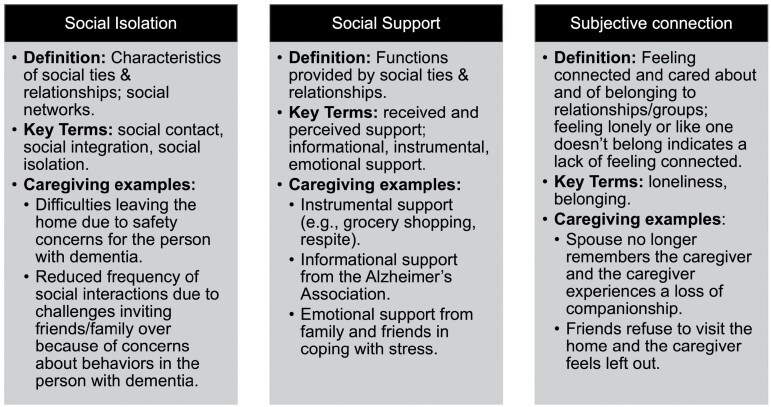

There are several dimensions of social relationships that are important for health and well-being. Holt-Lunstad et al. proposed a conceptual framework to describe and differentiate the key dimensions of social relationships that are associated with poor health and premature mortality. Our center uses this model and applies it to the caregiving context (Figure 1). This model defines social connection as an organizing construct that includes all dimensions of social relationships central to health (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017) and posits three primary dimensions. First, social isolation refers to characteristics of social ties and networks that are insufficient for health, such as infrequent visits/calls with family/friends. For caregivers, this may manifest as difficulties leaving the home due to limited time, safety concerns for the person with dementia, and/or reduced frequency of social interactions due to behavioral changes in the person with dementia that others may find challenging (e.g., incontinence). Second, social support refers to the functions that relationships provide, including information, instrumental assistance (e.g., activities of daily living), and emotional support. For caregivers, this may be reflected in instrumental support from family (e.g., grocery shopping, respite), information from the Alzheimer’s Association and physicians, and/or emotional support from family/friends in coping with stress. Third is the psychological experience of feeling isolated or connected (e.g., loneliness, belonging). Loneliness refers to the emotionally distressing experience of lacking a desired level of social connection and is often measured by the UCLA Loneliness Scale that intentionally does not use the term lonely to reduce stigma; the items of the short version are, “I lack companionship, I feel left out, and I feel isolated from others.” For ADRD caregivers, loneliness may occur in the context of a spouse no longer remembering the caregiver leading to a loss of companionship or friends refusing to visit the home, leading the caregiver feeling left out.

Figure 1.

Dimensions of social connection in the context of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias caregiving.

Research has documented that providing care for a family member or other close tie (e.g., lifelong friend) with dementia is linked to all three dimensions of social (dis)connection. First, changes in roles and responsibilities that accompany caregiving can lead to social isolation (Greenwood et al., 2018). For example, caregivers who live with the person they are caring for are more than twice as likely to report not being able to leave the home as much as they would like, and those who report an unmet need for professional long-term care services are almost four times as likely to report not being able to leave the home as much as they would like (Robison et al., 2009). Caregiving is also linked to reduced participation in social activities such as sports and community centers—with a stronger effect when the person with dementia has greater functional impairment (Clark & Bond, 2000). Second, changes in relationships that accompany caregiving can affect the availability as well as perceptions of emotional support, including not feeling understood by other family members or friends (Vasileiou et al., 2017). In contrast, high social support is associated with perceiving greater gains from providing care for a loved one (Leggett et al., 2021) and reduced stress (Wang et al., 2018). Finally, the quality of the relationship between the caregiver and the person with dementia changes as the disease progresses and many caregivers must manage the loss of an important relationship, which may lead to a lack of companionship, which is a component of loneliness (Beeson et al., 2000; Vasileiou et al., 2017). When loneliness occurs, it is strongly associated with reduced quality of life (Ekwall et al., 2005) and greater depressive symptoms (Beeson et al., 2000; Tuithof et al., 2015). While individuals naturally vary in the amount of social interaction they desire, loneliness is a dimension of social disconnection that is inherently distressing and thus may be particularly acceptable as an intervention target. For these reasons, loneliness is a central focus of our center and this article.

Several studies have investigated behavioral interventions to reduce loneliness in older adults (outside of the caregiving context). A randomized trial of behavioral activation focused on social activities provided to lonely, home-delivered meals clients found a significant reduction in loneliness (Bruce et al., 2021; Choi et al., 2020; Pepin et al., 2021); a randomized trial of Engage Psychotherapy (that uses behavioral activation principles) focused on social activities increased social–emotional quality of life in older adults reporting loneliness (Van Orden et al., 2021); and a program evaluation of an in-home depression collaborative care program (PEARLS) that includes problem solving and behavioral activation found reductions in loneliness for low-income older adults (Steinman et al., 2021). Additional approaches include technology programs (Czaja et al., 2013), peer companionship/friendly calling (Conwell et al., 2021), and group exercise (Mays et al., 2021). However, the current state of the science does not allow for definitive recommendations about what works to promote reduce loneliness in older adults (Hickin et al., 2021; Lutz et al., 2021). Furthermore, many promising interventions are multifaceted, intensive, and/or involve significant time out of the home, which may render them infeasible for many caregivers, indicating a need to study the compatibility of interventions with the responsibilities of ADRD caregivers.

A variety of behavioral interventions to reduce caregiver stress have demonstrated positive effects on burden, depression, subjective well-being, ability/knowledge, and symptoms of the care recipient (Brodaty et al., 2003) but most have little evidence to support improvements in any dimension of social connection—social isolation, social support, or loneliness—either because dimensions of social connection were not examined as outcomes or because interventions did not reliably improve social connection (Gaugler et al., 2018; Lykens et al., 2014). While social support is the most commonly examined dimension of caregiving interventions, a systematic review of behavioral interventions for caregivers reported inconclusive findings for the impact of interventions on social support (Cheng & Zhang, 2020). Taken together, there is a critical need for highly effective, evidence-based interventions for promoting social connection and/or reducing loneliness in ADRD caregivers.

Recommendations for Research to Promote Social Connection in ADRD Caregivers

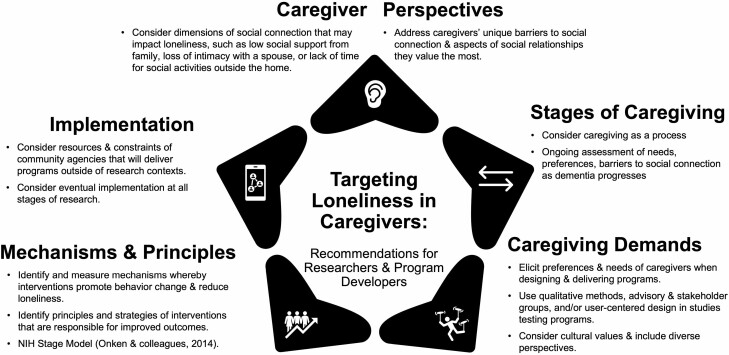

Our central premise is that to significantly impact social disconnection in caregivers for individuals with ADRD, a modular portfolio of mechanism-informed, principle-based behavioral interventions is needed that can meet a diverse set of needs and priorities while maximizing resources and reducing demands on caregivers. Such modular approaches are useful for problems that are complex and that change over time and also increase the likelihood of successful implementation outside of a research context (Lyon & Koerner, 2016). Next, we provide recommendations to address key limitations and gaps in the literature on social connection interventions for caregivers that are grounded in the recommendations of a 2021 report on dementia caregiving (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021) and describe how our center is guided by these recommendations (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Recommendations for research to promote social connection in caregivers.

First, incorporating the perspectives of ADRD caregivers in the design and testing of interventions, as well as in the delivery of interventions, is essential (see top of Figure 2). Programs to reduce loneliness are often underutilized (Lutz, 2021). To increase utilization, community stakeholders advocate for developing multicomponent interventions that allow for tailoring to individual needs and preferences, as well as including consumers in the process of developing and evaluating programs (Sabir et al., 2009). It may be especially important to include the perspectives of caregivers when addressing loneliness given competing demands for time, energy, and resources, as well as the diverse ways in which caregiving can affect social connection. Thus, in line with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s (2021) recommendation for examining outcomes prioritized by ADRD caregivers and individuals with dementia, we recommend including the voice of caregivers in all aspects of research and program development, including the use of qualitative methods to elicit preferences and priorities.

Interventions to address loneliness for ADRD caregivers may be most effective when considering caregivers’ perspectives instead of providing a one-size-fits-all intervention strategy. For example, interventions should consider the specific factors, including a lack of social supports and resources (Bunt et al., 2017), that contribute to loneliness for a given caregiver. Including which aspects of relationships are most meaningful and most challenging to address can promote a personalized approach to selecting the most acceptable, potent, and low-burden intervention strategies. Individuals experiencing loneliness can come to that experience via unique pathways (Cacioppo et al., 2015). For example, loss of emotional intimacy with a spouse, reduced support from family and friends, or less time to engage in meaningful social activities can all lead to loneliness in caregivers, but may require different intervention strategies. In addition, caregivers differ regarding their priorities for interventions. It is essential to understand a caregiver’s values and priorities around social relationships to promote behavior change that will result in reduced loneliness. Several studies have demonstrated the promise of behavioral activation for loneliness (reviewed above), which emphasizes taking action in line with one’s values. Asking caregivers what aspects of their relationships have changed because of caregiving, which changes resulted in loneliness, and which aspects of relationships they value most can guide intervention.

Second, considering the demands of caregiving when designing, testing, and implementing interventions is essential (right side of Figure 2). Providing care for a loved one requires resources—time, energy, and money—that must be considered when developing or recommending programs. Some of these resources may be more depleted for some caregivers than others, necessitating consideration of resources needed to engage in a program as well as the provision of a range of options, such as very brief programs for those with limited time, as well as more intensive options for those desiring more support. Preferences for program formats and delivery options vary depending on resources and perceived need for assistance, for example, group versus individual formats, in-person versus remote formats, professional versus peer-delivered, and self-guided versus supported. Considering diverse caregiver needs, preferences, and values regarding the type of program, intensity and duration, and delivery format, will ensure that programs are acceptable for caregivers and in line with evidence for supporting individually tailored approaches (Selwood et al., 2007).

Third, it is essential to consider caregiving as a process (right side of Figure 2), with stages that progress and demands that change over time (Gaugler et al., 2000). As such, programs for caregivers must continually assess caregiver needs and preferences and adapt correspondingly to ensure that programming is compatible with caregiving demands (Zarit, 2018). Some caregivers may prefer to include the person they are caring for in sessions or groups, while others may prefer to attend programs on their own to speak freely about stressors. Some caregivers may need or want to focus on developing skills to manage caregiving tasks, while others may need to focus on themselves as a person outside the caregiving context. Often neglected in caregiver services is addressing bereavement—providing services when the person with dementia has died.

Acceptability of behavioral interventions encompasses several domains (Sekhon et al., 2017). Within the caregiving context, these include perceived burden of the intervention (e.g., time, money, effort) given competing demands, the degree to which an intervention fits with caregivers’ values (e.g., supporting a loved one’s dignity, responsibility for family), the degree to which the intervention “makes sense” to caregivers, perceived effectiveness, and self-efficacy to complete the intervention. For researchers, assessing acceptability is one way to include the voice of caregivers. This can be done by incorporating qualitative methods—including focus groups and semistructured interventions—into intervention development and testing studies. Codesigning procedures via advisory groups may also be useful. Outside of a research context, assessing acceptability from the perspectives of both caregivers and those providing programs can address issues with implementation.

Some caregivers face challenges in leaving a person with dementia at home and may prefer telehealth programs, while others may long for time outside the home. Telehealth has shown promise in addressing loneliness, including with caregivers (Czaja et al., 2013). Some may prefer counselor-supported programs, while others prefer self-guided or mHealth delivery methods. Considering and asking about such preferences may produce more acceptable interventions and promote better outcomes and increased engagement. Personalizing programs to caregivers’ needs and preferences should also consider cultural differences and values, such as familism in Hispanic/Latino caregivers, which speaks to the high importance and value placed on family, including closeness, support, and loyalty (Balbim et al., 2020; Rote et al., 2019).

Fourth, we suggest that research on interventions to promote social connection will be most impactful by examining mechanisms (Nielsen et al., 2018) and intervention principles associated with improvements (Onken et al., 2014; Figure 2, bottom left), in line with recommendations from an The National Institute of Mental Health-sponsored workshop on social disconnection in later life (Lutz, 2021; Necka et al., 2021). Without clarity on why an intervention produces positive outcomes (the mechanism) and how the intervention does so (the principle), it is challenging to effectively deploy interventions outside of research contexts: knowing why an intervention works and how it produces effects guide implementation efforts that address community needs, cultural variations, and real-world challenges while retaining essential ingredients to produce desired effects. The importance of measuring mechanisms and identifying intervention principles is essential for studying social connection. Given that most studies and community programs provide social contact, and that pathways underlying social disconnection are complex and multiple, it is important to understand the means by which interventions produce effects that will generalize outside of research contexts.

The state of the science in loneliness interventions is stymied by a lack of understanding of mechanisms of action (Lutz et al., 2021). Mechanisms, whereby interventions reduce loneliness, may be identified by theories of behavior change. Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000) is a psychological theory of motivation and behavior change that has been applied to intervention development and testing because it specifies key psychological processes that effective interventions should target to produce sustained behavior change. It posits that interventions motivate health-promoting behaviors (including increased social engagement, social activity, and repairing relationship conflict) when interventions simultaneously satisfy innate human needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (cf., belonging), thereby producing intrinsic motivation for healthy behaviors (i.e., absorption, vigor, and dedication). Mechanisms may also involve other pathways, whereby social connection affects health. For example, it is well- established that quality social relations and the support they provide during stressful times can buffer the detrimental stress-related psychological and physiological effects that mediate health and disease (Heffner et al., 2011; Uchino, 2006). Indeed, ADRD caregivers who report high social support appear to be buffered from negative effects of caregiving (Wang et al., 2018). Furthermore, lonely individuals show evidence of dysregulated stress systems (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2003). Together, these findings suggest that improved stress adaptation may function as a mechanism, whereby interventions for loneliness improve outcomes for ADRD caregivers. Studies investigating behavioral interventions to promote social connection will be most useful when they explicitly test theoretically grounded mechanisms—and associated intervention principles—whereby interventions reduce loneliness.

Finally, considering dissemination and implementation at all stages of research is essential (Figure 2, middle left). A deployment-focused process for intervention science considers characteristics of interventions that will produce successful deployment in real-world settings, including implementation with fidelity and dissemination to relevant settings (Onken et al., 2014). Given that social connection is not typically addressed in health care settings, interventions for caregivers may be most potent when they are compatible with the needs and demands of community agencies such as the Alzheimer’s Association, Area Agencies on Aging, senior centers, senior living communities, and agencies that offer wellness programming. Interventions must simultaneously address needs and preferences to promote acceptability and full engagement, while also addressing resources and constraints of agencies delivering programs so that programs can be delivered with high fidelity (O’Malley & Qualls, 2020). Considering eventual implementation at the earliest stages of intervention development and testing can promote successful and rapid deployment and is essential for increasing the public health impact of research on interventions for ADRD caregivers (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021).

Future Directions

Given that the complexity of the biopsychosocial context of caring for a family member with ADRD and the varied challenges faced by caregivers preclude the possibility of a one-size-fits-all strategy to increasing social connection, we suggest that an optimal intervention model should allow personalization to accommodate a diverse set of circumstances that function as barriers to social connection, such as type of caregiving responsibilities, the nature of the relationship with the person with dementia, dementia stage, and prior relationship functioning. These dimensions can lead to varied and diverse barriers to social connection, ranging from practical barriers (e.g., lack of resources, knowledge, finances), emotional barriers (e.g., fear, guilt), and difficulties in the relationship with the person with dementia (e.g., grief, sadness, conflict). In addition, the same caregiver may need new strategies over the course of the disease as the context and stressors associated with caregiving change. Furthermore, there may be additional interpersonal processes, self-regulation, or stress mechanism targets that can optimize interventions to ensure behavior change that supports social engagement.

The objective of our Roybal Center is to produce a set of evidence-based modules that can be flexibly applied to meet caregivers’ diverse and changing needs, and diverse and changing service provider environments, while maximizing resources and reducing demands on caregivers. The knowledge gained by developing and testing this portfolio will also generalize to other challenges facing caregivers, such as stress and depression, as well as to other populations of older adults who may be particularly vulnerable to loneliness, such as those with increasing physical disability (Lutz et al., 2016) or those coping with life transitions, such as retirement or relocation to senior living communities (Choi & DiNitto, 2016), as well as those managing depression and suicide ideation (Lutz et al., 2021).

Finally, the consequences of loneliness and isolation may have been exacerbated during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, as estimates indicate that unpaid caregivers (including those caring for loved ones with dementia) were significantly more likely to experience serious suicidal thoughts compared to noncaregivers; however, caregivers who reported having someone to rely on for social support had significantly lower likelihood of suicide ideation and other mental health problems (Czeisler et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and need for physical distancing have underscored the importance of maintaining supportive, positive social relationships for health and well-being (Kim & Jung, 2021; Macdonald & Hulur, 2021). Notably, it also has highlighted the need to remain nimble and flexible in modes of delivery for behavioral interventions—including remote delivery, and further testing of these telehealth delivery approaches should be a priority.

Conclusion

Social disconnection is a primary mental and physical health risk for older adults (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2020). We implore multidisciplinary teams of researchers and community-based service providers to apply their expertise—in dementia caregiving, gerontology, social relationships and connection (including loneliness, social support, and isolation), behavior change, adaptive behavioral intervention development, implementation science, among others—to advancing innovative, mechanism- and principle-driven interventions to improve social relationships and reduce loneliness in ADRD caregivers. Promoting social connection has the potential to buffer caregiving stress and enhance positive aspects of the caregiving experience. It is a strengths-based approach with effects on numerous domains of health that capitalizes on the fact that our connections with one another are a powerful form of medicine and healing.

Contributor Information

Kimberly A Van Orden, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York, USA.

Kathi L Heffner, School of Nursing, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York, USA.

Author Note

For more information on the Rochester Roybal Center for Social Ties & Aging Research, including funding announcements, please visit the Center’s website: https://research.son.rochester.edu/rocstarcenter/

Funding

This work is supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (P30AG064103).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Balbim, G. M., Magallanes, M., Marques, I. G., Ciruelas, K., Aguinaga, S., Guzman, J., & Marquez, D. X. (2020). Sources of caregiving burden in middle-aged and older Latino caregivers. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 33(4), 185–194. doi: 10.1177/0891988719874119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeson, R. A. (2003). Loneliness and depression in spousal caregivers of those with Alzheimer’s disease versus non-caregiving spouses. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 17(3), 135–143. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(03)00057-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeson, R., Horton-Deutsch, S., Farran, C., & Neundorfer, M. (2000). Loneliness and depression in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease or related disorders. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 21(8), 779–806. doi: 10.1080/016128400750044279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty, H., Green, A., & Koschera, A. (2003). Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51(5), 657–664. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, M. L., Pepin, R., Marti, C. N., Stevens, C. J., & Choi, N. G. (2021). One year impact on social connectedness for homebound older adults: Randomized controlled trial of tele-delivered behavioral activation versus tele-delivered friendly visits. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(8), 771–776. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunt, S., Steverink, N., Olthof, J., van der Schans, C. P., & Hobbelen, J. S. M. (2017). Social frailty in older adults: A scoping review. European Journal of Ageing, 14(3), 323–334. doi: 10.1007/s10433-017-0414-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, S., Grippo, A. J., London, S., Goossens, L., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Loneliness: Clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 238–249. doi: 10.1177/1745691615570616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carers UK. (2015). Facts about carers: Policy briefing. https://www.carersuk.org/for-professionals/policy/policy-library/facts-about-carers-2015 [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S. T., & Zhang, F. (2020). A comprehensive meta-review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on nonpharmacological interventions for informal dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 137. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01547-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi, W., Graf, E., Hughes, L., Hastie, J., Khatutsky, G., Shuman, S., Jessup, E. A., Karon, S., & Lamont, H. (2019). Older adults with dementia and their caregivers: Key indicators from the National Health and Aging Trends Study. The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/community-dwelling-older-adults-dementia-their-caregivers-key-indicators-national-health-aging [Google Scholar]

- Choi, N. G., & DiNitto, D. M. (2016). Depressive symptoms among older adults who do not drive: Association with mobility resources and perceived transportation barriers. The Gerontologist, 56(3), 432–443. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, N. G., Pepin, R., Marti, C. N., Stevens, C. J., & Bruce, M. L. (2020). Improving social connectedness for homebound older adults: Randomized controlled trial of tele-delivered behavioral activation versus tele-delivered friendly visits. American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(7), 698–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. S., & Bond, M. J. (2000). The effect on lifestyle activities of caring for a person with dementia. Psychology Health & Medicine, 5(1), 13–27. doi: 10.1080/135485000105972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conwell, Y., Van Orden, K. A., Stone, D. M., McIntosh, W. L., Messing, S., Rowe, J., Podgorski, C., Kaukeinen, K. A., & Tu, X. (2021). Peer companionship for mental health of older adults in primary care: A pragmatic, nonblinded, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(8), 748–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja, S. J., Loewenstein, D., Schulz, R., Nair, S. N., & Perdomo, D. (2013). A videophone psychosocial intervention for dementia caregivers. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(11), 1071–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler, M. E., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., Weaver, M. D., Robbins, R., Facer-Childs, E. R., Barger, L. K., Czeisler, C. A., Howard, M. E., & Rajaratnam, S. M. W. (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69 (32), 1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior [Review]. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwall, A. K., Sivberg, B., & Hallberg, I. R. (2005). Loneliness as a predictor of quality of life among older caregivers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(1), 23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03260.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler, J. E., Davey, A., Pearlin, L. I., & Zarit, S. H. (2000). Modeling caregiver adaptation over time: The longitudinal impact of behavior problems. Psychology & Aging, 15(3), 437–450. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.15.3.437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler, J. E., Reese, M., & Mittelman, M. S. (2018). The effects of a comprehensive psychosocial intervention on secondary stressors and social support for adult child caregivers of persons with dementia. Innovation in Aging, 2(2), igy015. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igy015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, N., Mezey, G., & Smith, R. (2018). Social exclusion in adult informal carers: A systematic narrative review of the experiences of informal carers of people with dementia and mental illness. Maturitas, 112, 39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2003). Loneliness and pathways to disease. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 17(Suppl. 1), S98–S105. doi: 10.1016/S0889-1591(02)00073-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, K. L., Waring, M. E., Roberts, M. B., Eaton, C. B., & Gramling, R. (2011). Social isolation, C-reactive protein, and coronary heart disease mortality among community-dwelling adults. Social Science & Medicine, 72(9), 1482–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickin, N., Kall, A., Shafran, R., Sutcliffe, S., Manzotti, G., & Langan, D. (2021). The effectiveness of psychological interventions for loneliness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 88, 102066. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Robles, T. F., & Sbarra, D. A. (2017). Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. American Psychologist, 72(6), 517–530. doi: 10.1037/amp0000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. H., & Jung, J. H. (2021). Social isolation and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-national analysis. The Gerontologist, 61(1), 103–113. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovaleva, M., Spangler, S., Clevenger, C., & Hepburn, K. (2018). Chronic stress, social isolation, and perceived loneliness in dementia caregivers. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 56(10), 36–43. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20180329-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett, A. N., Meyer, O. L., Bugajski, B. C., & Polenick, C. A. (2021). Accentuate the positive: The association between informal and formal supports and caregiving gains. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(7), 763–771. doi: 10.1177/0733464820914481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, J. (2021). Addressing social disconnection in late life: From outcomes research and calls-to-action to effective intervention science. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(3), 311–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, J., Morton, K., Turiano, N. A., & Fiske, A. (2016). Health conditions and passive suicidal ideation in the survey of health, ageing, and retirement in Europe. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71(5), 936–946. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, J., Van Orden, K. A., Bruce, M. L., & Conwell, Y.; Members of the NIMH Workshop on Social Disconnection in Late Life Suicide (2021). Social disconnection in late life suicide: An NIMH Workshop on state of the research in identifying mechanisms, treatment targets, and interventions. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(8), 731–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.01.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykens, K., Moayad, N., Biswas, S., Reyes-Ortiz, C., & Singh, K. P. (2014). Impact of a community based implementation of REACH II program for caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients. PLoS One, 9(2), e89290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, A. R., & Koerner, K. (2016). User-centered design for psychosocial intervention development and implementation. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 23(2), 180–200. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, B., & Hulur, G. (2021). Well-being and loneliness in Swiss older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of social relationships. Gerontologist, 61(2), 240–250. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays, A. M., Kim, S., Rosales, K., Au, T., & Rosen, S. (2021). The Leveraging Exercise to Age in Place (LEAP) Study: Engaging older adults in community-based exercise classes to impact loneliness and social isolation. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(8), 777–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system. T. N. A. Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). Meeting the challenge of caring for persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers: A way forward. T. N. A. Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Necka, E. A., Rowland, L. M., & Evans, J. D. (2021). Social disconnection in late life mental illness: Commentary from the national institute of mental health. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(8), 727–730. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, L., Riddle, M., King, J. W., NIH Science of Behavior Change Implementation Team, Aklin, W. M., Chen, W., Clark, D., Collier, E., Czajkowski, S., Esposito, L., Ferrer, R., Green, P., Hunter, C., Kehl, K., King, R., Onken, L., Simmons, J. M., Stoeckel, L., Stoney, C., Tully, L., & Weber, W. (2018). The NIH Science of Behavior Change Program: Transforming the science through a focus on mechanisms of change. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 101, 3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, K. A., & Qualls, S. H. (2020). Application of treatment fidelity in tailored caregiver interventions. Aging & Mental Health, 24(12), 2094–2102. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1647134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken, L. S., Carroll, K. M., Shoham, V., Cuthbert, B. N., & Riddle, M. (2014). Reenvisioning clinical science: Unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(1), 22–34. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, K. (1997). The male experience of caregiving for a family member with Alzheimer’s disease. Qualitative Health Research, 7(3), 391–407. doi: 10.1177/104973239700700305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pepin, R., Stevens, C. J., Choi, N. G., Feeney, S. M., & Bruce, M. L. (2021). Modifying behavioral activation to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(8), 761–770. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison, J., Fortinsky, R., Kleppinger, A., Shugrue, N., & Porter, M. (2009). A broader view of family caregiving: Effects of caregiving and caregiver conditions on depressive symptoms, health, work, and social isolation. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64(6), 788–798. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rote, S. M., Angel, J. L., Moon, H., & Markides, K. (2019). Caregiving across diverse populations: New evidence from the national study of caregiving and Hispanic EPESE. Innovation in Aging, 3(2), igz033. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igz033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabir, M., Wethington, E., Breckman, R., Meador, R., Reid, M. C., & Pillemer, K. (2009). A community-based participatory critique of social isolation intervention research for community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 28(2), 218–234. doi: 10.1177/0733464808326004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon, M., Cartwright, M., & Francis, J. J. (2017). Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 88. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selwood, A., Johnston, K., Katona, C., Lyketsos, C., & Livingston, G. (2007). Systematic review of the effect of psychological interventions on family caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of Affective Disorders, 101(1–3), 75–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siriopoulos, G., Brown, Y., & Wright, K. (1999). Caregivers of wives diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease: Husbands’ perspectives. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 14(2), 79–87. doi: 10.1177/153331759901400209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman, L., Parrish, A., Mayotte, C., Bravo Acevedo, P., Torres, E., Markova, M., Boddie, M., Lachenmayr, S., Montoya, C. N., Parker, L., Conton-Pelaez, E., Silsby, J., & Snowden, M. (2021). Increasing social connectedness for underserved older adults living with depression: A pre-post evaluation of PEARLS. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(8), 828–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuithof, M., ten Have, M., van Dorsselaer, S., & de Graaf, R. (2015). Emotional disorders among informal caregivers in the general population: Target groups for prevention. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 23. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0406-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino, B. N. (2006). Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden, K. A., Areán, P. A., & Conwell, Y. (2021). A pilot randomized trial of engage psychotherapy to increase social connection and reduce suicide risk in later life. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(8), 789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Barreto, M., Vines, J., Atkinson, M., Lawson, S., & Wilson, M. (2017). Experiences of loneliness associated with being an informal caregiver: A qualitative investigation. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 585. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z., Ma, C., Han, H., He, R., Zhou, L., Liang, R., & Yu, H. (2018). Caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease: Moderation effects of social support and mediation effects of positive aspects of caregiving. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(9), 1198–1206. doi: 10.1002/gps.4910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit, S. H. (2018). Past is prologue: How to advance caregiver interventions. Aging & Mental Health, 22(6), 717–722. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1328482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]