Abstract

Understanding the determinants of crime reporting is fundamental to developing responsive judicial services that seek to pursue justice while fostering good relations with citizens. Building on Carpenter’s (Carpenter, D. (2014). Reputation and power: Organizational image and pharmaceutical regulation at the FDA. Princeton University Press.) dimensions of reputation and the principles of procedural justice, this article aims to explore the influence of institutional reputation on crime reporting decisions for the Mexican case. To test three hypotheses at an individual level, nested logit models were estimated with information from a victimization survey in Mexico over a 9-year period. Findings suggest that time spent in prosecutors’ offices and the perception of untrustworthiness, related to two of the reputation dimensions described in this study’s framework, are negatively associated to the probability of reporting a crime. Our results have implications for public policy regarding the treatment by the police of the population reporting a crime. This is particularly relevant in regions such as Latin America, characterized by high victimization and the lack of adequate procedural justice in situations of contact between the public and police authorities.

Keywords: Crime reporting, Victimization survey, Institutional reputation, Logit model, Mexico

Introduction

The decision to report a crime to the authorities has been shown to be determined by factors such as the victim’s demographic characteristics, the seriousness of the crime, and the offender’s characteristics (Hart & Rennison, 2003; Kruttschnitt & Carbone-Lopez, 2009; Skogan, 1984). Studies have also found that another important determinant is social influence, mainly advice received from others, such as family, acquaintances, and bystanders (Greenberg & Beach, 2004; Greenberg & Ruback, 2012; Spelman & Brown, 1981). Greenberg and Beach (2004, pp. 182), for example, found that “victims who were advised to call the police were more than 12 times more likely to report the crime than those who either did not receive advice, or those who were advised not to call the police.” This might be due to the fact that when faced with difficult decisions, “citizens often place the responsibility for making the decision on others” (Spelman & Brown, 1981, pp.122).

Interpersonal influence has been studied since the 1960s in order to explain victims’ proclivity to report a crime (Darley & Latané, 1968; Rosenthal, 1964; Bickman, 1979). The bystander intervention model refers to a series of behaviors that include noticing and interpreting an event, taking responsibility, and finally, reporting (Latané & Darley, 1970). Perceptions of who is responsible for reporting a crime are the major determinants of intervention (Allen, 1971; Tilker, 1970). Since the development of the model, analyses of the decision-making process have become more complex, although still rely on Latané and Darley’s model. They include variations in reporting rate that depend on the magnitude of the crime, that is, how much is stolen (Hindelang & Gottfredson, 1976), the impact of a victim’s emotional state (Mintz & Mill, 1971), and differences between bystander and victim eyewitnesses (Buckhout, 1974). In the 1970s and 1980s, the set of determinants for victim crime reporting became more sophisticated and was developed according to three broad groups: (a) crime specific correlates (Gottfredson & Gottfredson, 1987), (b) individual specific (Garofalo, 1977; Riger, 1981), and (c) environment specific (Feins, Peterson & Rovetch, 1983; Ruback et al., 1984).

More recently, Goudriaan (2006) developed a socio-ecological theoretical model that transforms victims’ decision-making process into a “cost–benefit” analysis to explain crime reporting. Simply put, victims make an unconscious analysis of the costs (transactions with the authorities, transport and time involved, risk of reprisals), and benefits (prevent other crimes against themselves or others, punish the aggressor, take revenge for the event, recover stolen items, receive compensation or insurance payouts) of reporting. In this study, the control variables used included the victims’ norms and culture, their social environment, the existence of informal resolution instructions, and the degree of individualism and trust in the authorities. Later studies expanded on these original control variables with Baumer and Lauritsen (2010) focusing on the type and seriousness of the crime as well as on the harm suffered by the victim, and Tarling and Morris (2010) considering the crime context, the socio-economic characteristics of the victim, or the victim’s relationship with the aggressor. Nevertheless, evidence based on comparative studies between countries remains scarce due to the lack of a consistent methodological strategy in studies of victimization across countries (Zakula, 2015).

Research into predictors of crime reporting by victims has diversified to become a multi-disciplinary endeavor (Tjaden et al., 2000). The most common findings show three clusters of crime reporting motivations: (i) crime specific: there is a higher level of reporting for motor vehicle theft (Rand & Catalano, 2007), or when the crime involves a weapon, results in injury to victims, or causes significant financial loss (Baumer et al., 2010); (ii) individual specific: crimes are more likely to be reported when the victims are elderly, women, African American, or poor (Hart & Rennison, 2003); and (iii) environment specific: the degree of neighborhood social cohesion and confidence in police effectiveness will influence the probability of victims reporting a crime to the police (Goudriaan, Wittebrood & Nieuwbeerta, 2006). The latter may include social context elements that influence the discourse on reporting to the police such as racial differences (Catalano, 2006) and community-oriented policing (Schnebly, 2008).

Some of these studies propose a new framework for distinguishing between situational (rational and normative reporting decisions) and contextual (community level) influences on reporting decisions (Goudriaan, Lynch & Nieuwbeerta, 2004). Obviously, confidence in the police alludes to procedural justice, that is, to the equality of processes in contact situations. Citizens’ opinions regarding the trustworthiness and legitimacy of the police are based on the way in which they have been treated by the police, rather than the result of the criminal encounter (Fondevila, 2008; Thibaut & Walker, 1975; Tyler, 1990; Tyler & Huo, 2002). Procedural justice theory has two distinct components: (1) the quality of decision-making procedures (the police provide a “voice” to those involved and behave professionally, competently, and impartially); and (2) the quality of treatment, that is, if police treat the public with dignity and respect. Current research suggests that the police may foment greater legitimacy, cooperation (in the form of crime reporting), and compliance when they deal with citizens in a procedurally fair way.

Trust in the police and the legal system increases willingness to report crimes (Goudriaan, 2006; Warner, 2007; Vilalta & Fondevila, 2018), especially if this trust includes the perception that the police are effective against crime (Kääriäinen & Sirén, 2011). It is precisely here that reputation, related to procedural justice perception, is seen as a social influence mechanism, and plays a fundamental role in the crime reporting decision process. Victims will decide to report a crime according to their perception of the institution. The concept of reputation derives from public administration studies and refers to a set of social beliefs about an organization’s past actions and future prospects based on its perceived capacity, roles, and obligations (Fombrun, 1996). An important feature of this concept is that among the organization’s constituents, beliefs around its reputation are so continuously shared, and with such minimal variation that the reputation obtains an “air of objectivity” and impacts perceptions of the organization even among those who have never had any direct contact with it (Carroll, 2013).

The purpose of incorporating this notion into the study of crime reporting is not to replace the analysis of victims’ rational choice, but rather to complement it with another layer of analysis within the context of procedural justice. Applied to crime reporting, this means that even when victims have not received advice or arguments regarding the immediate reporting of a crime, or when they have never had direct contact with the police institution, they have nevertheless already been socially influenced through reputation, which affects their decision to report the crime. As it involves individual perceptions that are influenced by social perceptions regarding the police, this concept interrelates two of the abovementioned clusters: (ii) individual decisions, and (iii) environment specific. In practice, this means that victims may already have an idea of what can be expected should they decide to report a crime to the police, and their expectations are commonly related to three dimensions: treatment, result of the investigation, and fairness and justice (Carpenter, 2014).

In this context, this paper aims to explore the influence of reputation on crime reporting decisions and more specifically, the importance of each of these three dimensions for the Mexican case. In Mexico, in contrast to other judicial systems such as the one in the US, most police duties are related to crime prevention. Their main functions are to patrol, to respond to citizens’ calls, and to assist people in need. However, they are not the judicial body responsible for receiving and processing crime reports. This function is assumed by the local prosecution offices (MP, in Spanish: ministerio público). This institution oversees most of the judicial procedures related to the registration and pursuit of justice, such as crime investigations, witnesses’ calls, evidence obtention, and accusation generation.

If a citizen wants a crime to be recorded in the official registry and investigators to begin working on the case, the crime must be reported directly to the MP offices. These offices depend on the courts of each of the 32 Mexican states and have local laws and regulations that result in important differences in the procedures followed by each. Some of the consequences of this structure are low crime reporting rates, usually below 11.4% (INEGI, 2020), a high perception of corruption (61.7% think the MP is corrupt), a generalized negative perception of its performance (only 10.4% think the MP is very effective) and a high report of poor attention (only 8% said they had received excellent attention). Mexico is, therefore, a good case study to explore the link between reputational aspects of the MP and the crime reporting decision, as the offices are characterized by incompetence, high workloads and insufficient resources, illegitimacy, and lack of responsiveness by the criminal justice system (Zepeda Lecuona, 2014).

Dimensions in Crime Reporting

According to Carpenter (2014), three dimensions impact how reputation affects the crime reporting decision. The first dimension, treatment reputation, refers to victims’ expectations of how they will be treated by the police while reporting a crime. This has been found to be an important determinant of victims’ reporting decisions as they will only do so if the criminal justice system can deal with the crime without causing undue inconvenience to the victim (Spelman & Brown, 1981). Even high costs of transportation and parking, or excessive time lost at the office will negatively impact the reporting decision (Greenberg & Ruback, 2012). Of course, a person has no way of knowing exactly how they will be treated by the police, and hence the reliance on the police’s reputation, based on opinions and experiences of other victims who have reported a crime in the past and shared these experiences with family, friends, media, and in surveys, among others.

The second dimension that can affect a victim’s decision to report a crime is the efficacy reputation of the police. This refers to a victim’s expectation of how proficiently and effectively an investigation will be handled by the police. The efficacy reputation is related to what Carpenter identified as an organization’s performative reputation, which expresses the audience’s judgment “of the quality of the entity’s decision making and its capacity for effectively achieving its ends and announced objectives” (pp. 46). In the case of the police, the performative reputation is closely related to another item of Carpenter’s reputation components: the technical reputation, which “includes variables such as scientific accuracy, methodological prowess, and analytic capacity” (pp. 46–47). These components define the degree to which audiences perceive an organization as an expert authority on the issues it is responsible for.

The last dimension is whether people perceive the office as corrupt or unfair. The fairness reputation refers to a victim’s expectation of corruption-free justice. This includes two aspects: On one hand, the moral reputation, which expresses the public’s feeling about the means and ends of an organization, and includes its ethical behavior, its transparency, and its commitment to human considerations, among others. On the other hand, the legal-procedural reputation “is related to the equity of the processes by which [the] behavior is generated” (pp. 47). The fairness reputation, thus, includes the expectation that the police will follow procedures, respect the rights of victims and offenders, and abstain from corruption or external influences, among other things.

Of the three dimensions of the police reputation, the fairness reputation is the most difficult for a citizen to assess. While the treatment and efficacy reputations are easier to evaluate through publicly available information and trustworthy accounts from acquaintances, the fairness reputation carries at least two burdens: (a) corruption is likely to be hidden by both the police and citizens who have benefitted from it, and (b) given the discretionary powers of the police, it is difficult to separate corruption from practices that might be considered unethical but not necessarily corrupt (Newburn, 1999; Roebuck & Barker, 1974).

The above three dimensions are profoundly related with the four main elements of procedural justice that relate to the perceived fairness of a process, based on an individual’s experience: (1) neutrality, (2) respect, (3) trustworthiness, and (4) voice (Lind & Tyler, 1988; Skogan & Frydl, 2004). Generally, people react favorably when they think the police are impartial: for those in contact with the police, receiving respectful, polite, and dignified treatment is fundamental (Tyler, 1990).

This means that the police explain their decisions to those involved and allow them a voice in the decisions that affect them, for example, by giving them the opportunity to explain their situation or version of the facts before the police decides how to proceed (Murphy & Mazerolle, 2018). In this regard, procedural justice can be understood as a key predictor of public trust in the police and consequently, in the context of our study, of the institutional reputation of the Public Prosecutor (Hohl et al., 2010; Jackson, et al., 2012; Murphy et al., 2014; Wolfe, et al., 2016).

It has been observed that police procedural justice can foment willingness to cooperate with the police (Murphy, 2015; Murphy & Barkworth, 2014; Murphy & Cherney, 2012; Sunshine & Tyler, 2003). This is based on the idea that the effects of procedural justice are a function of the processes of social identity (Lind & Tyler, 1988; Tyler & Blader, 2000). Fair treatment transmits social value to the members of a social group and reaffirms both identity and the individual’s connection with society (Bradford et al., 2014).

Procedural justice promotes police legitimacy and obedience to the police (Murphy et al., 2015) by reinforcing group social identity and, consequently, a greater proclivity to crime reporting. As such, it is related to an improvement in the institutional reputation of the police and judiciary. Murphy (2015) demonstrated that young people are especially sensitive to procedural justice, and thus, it is more effective in encouraging young people to report than it is for adults. Nevertheless, the studies of Murphy and Barkworth (2014), together with those of Wolfe et al. (2016), show that even in adults, victims are more sensitive to expressions of police procedural justice precisely because after victimization, they are more insecure about their status in society.

Given the above, in order to incorporate individual victim elements in the decision to cooperate through crime reporting, their willingness to report a crime should also be considered. The police largely depend on public cooperation and reporting to do their job. If citizens did not report crimes after an event, a high proportion would go undetected by the police (Vilalta & Fondevila, 2020). A growing body of research suggests that the best way for the police to increase the probability of public cooperation is to be perceived as a legitimate authority (Nix, 2017).

A consistent issue in this line of research is that citizens are more likely to view the police as legitimate when they exercise their authority in a procedurally fair manner (Jackson, et al., 2012; Mazerolle, et al., 2012; Tyler, 1990; Tyler & Huo, 2002). Many crimes come to police attention only once they have already been committed and offenders have left, that is, when citizens report the crime to the police. Similarly, police investigations depend largely on the information provided by witnesses and victims to help solve cases. If citizens do not feel inclined to provide useful information to the police, their work becomes that much more difficult (Nix, 2017). Simply put, when individuals consider that police actions are procedurally fair, they are more inclined to perceive them as a legitimate authority. At the same time, it is more likely that they will cooperate with the police by reporting crimes and providing information. Thus, police procedural justice ultimately leads to cooperation and higher levels of crime reporting.

In sum, public willingness to report crimes to the police forms part of a broader set of factors linked to police cooperation, legal compliance, and the acceptance of the decisions of legal authorities (Bradford et al., 2014; Mazerolle et al., 2013; Tyler & Huo, 2002); however, in contrast to cooperation and compliance, it reflects a particular willingness that centers on prospective and voluntary behavior (Rengifo et al., 2019). Intentions to report have also been linked to the perceived trustworthiness of the police (Sunshine & Tyler, 2003; Tyler & Fagan, 2008; Tyler & Huo, 2002). Evaluations of the police, in terms of instrumental concerns such as police effectiveness, can also impact reporting intentions (Bradford et al. 2014).

Crime Reporting in Mexico and Latin America

Literature on reporting is scarce in the Latin American context, especially studies that look directly at crime reporting. The vast majority only analyze levels of reporting for specific crimes, particularly violence against women, whose reporting is traditionally the most studied in the region. Literature on the factors that determine crime reporting of the latter violence is broadly divided into two areas: (a) the difficulties, obstacles, and filters of the judicial system that discourage reporting; and (b) challenges faced by women to report (for example, fear of reprisals, guilt, shame, demographic, and/or socio-economic conditions). In a study in Cuzco (Peru), Sierra et al. (2014) found that the highest levels of reporting of intimate partner domestic violence (37% of interviewees suffered physical abuse and 48% non-physical) were registered in cases of (a) greater intensity and chronicity of abuse (reflected in physical abuse and high levels of anxiety), (b) labor market insertion (working outside of the home), (c) older groups (age group), and (d) membership of women’s associations.

Another line of research on the issue analyzes the judicial system. For example, Casas Becerra and González-Ballesteros (2004) study how prejudices held by the police, forensic experts, prosecutors, and judges are associated to low levels of reporting sexual assault in Chile. Similarly, López-Valdéz (2014) studied the processes of revictimization in cases of sexual assault in the Mexican prison system, such as lack of credibility, depersonalization, and victim blaming, lack of information and privacy, inadequate spaces, and prejudices regarding victimization. These factors, strictly related to the judicial treatment received, discourage the reporting of sexual crimes. In Colombia, for example, Sotelo Barrios and González Rubio (2006) report that, during the legal process, this type of violence does not receive the necessary medical attention or psychological treatment, nor is there an attempt to reconstruct the social fabric with the support of social actors who surround the victim.

These patterns of behavior of the victim (resistance to reporting for fear of reprisals) and the judicial system (revictimization and institutional resistance to reporting) are repeated with minimal variation in Peru (Espinoza-Barrera, 2016), Ecuador (Boiraa, Carbajosa & Méndez, 2016), Brazil (Ferreira Amendola, 2009), and Argentina (Birgin & Gherardi, 2008). In Mexico and Colombia (Jiménez Vargas & Casas-Casas, 2012), in addition to the above, other crimes are included, such as femicide (Incháustegui Romero, Barajas & de la Paz, 2012) or extortion (Pérez Morales, et al., 2015). In the latter cases, relatives of the victim, in the case of femicides, or victims themselves, in the case of extortion, fear reprisals from aggressors, distrust institutions as reflections of the revictimization to which they have been subjected, and frequently face considerable obstacles in verifying their victimization.

All the above are specific case studies that include determinants of crime reporting associated with the crime under study, for example, the revictimization of victims of sexual crimes that occurs within prosecutors’ offices. Given this, there is a growing body of literature on crime reporting in the region, based on victimization surveys. The systematic application of victimization surveys that began in the region almost 20 years ago in Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Ecuador, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela, has meant that the majority of studies on crime reporting have been strengthened by data and empirical material.

There are two areas of analysis within this context. The first, well developed area looks at the consequences of low crime reporting without delving into an analysis of the determinants of reporting. For example, studies in Chile on low crime reporting describe the increase in the dark figure of crimes as an issue of the lack of procedural justice (Álvarez & Fuentes, 2005; Dammert, 2009; Dammert & Zúñiga, 2007; Dammert et al., 2010), while others look at the consequences of low crime reporting on crime impunity: without crime reporting there is no possibility of crime enforcement, meaning that crimes go unpunished; and authorities are unaware of the magnitude of the problem and do not establish focused public security policies (Benavente & Cortés, 2006). However, none of these studies investigate the determinants of crime reporting.

The second line of investigation concentrates on the factors that determine the propensity to report a crime. Generally, the studies develop statistical models that, once again, include two considerations as explanations for crime reporting: characteristics of the crime and socio-economic conditions of individuals, and trust in legal institutions, including attitudes toward the prosecutor. In this regard, Quinteros (2014) indicates that younger, married men with lower socio-economic and education levels are the least likely social group to report a crime in Chile, while Duce (2018) found that factors such as labor situation, education level or economic losses associated with the crime have a significant impact on the decision to report to public institutions.

Regarding people's attitudes toward the prosecutor, Zepeda Lecuona (2014) analyzed the role of favorable/ unfavorable attitudes in levels of crime reporting in Mexico. He notes that high levels of distrust (only 6.98% of respondents claimed to have significant confidence in the police in the survey used for the study) substantially explain the low crime reporting in Mexico. This attitude adds to the generally low credibility and negative perception of the capacity of security and legal institutions in the country. More recently, Vilalta et al. (2022) study the early impact of anti-COVID-19 measures on crime reporting in Mexico City and, consequently, on criminal investigations by the local prosecutor's office.

Similarly, comparative analyses have been conducted between the different regions of a single country. In Colombia, Mancera (2008) compared the rates of police effectiveness with the level of reporting between regions with and without the presence of guerilla activity (more efficient police and less guerilla activity determined a higher rate of reporting). In Mexico, Zakula (2015) accounted for the difference in rates of reporting between States in two ways: the variation in type and seriousness of crimes occurring with greatest frequency; and the circumstances under which a report is made, for example, the average time involved, perceptions on treatment, and the result of the report.

Unfortunately, surveys are still not sufficiently standardized for country comparisons (Londoño et al., 2002; Balán, 2011; Lagos & Dammert, 2012) although some effort has been made for inter-regional comparisons on a theoretical level (Sozzo, 2003). Nevertheless, there is still a shortage of studies compared to the level and depth of those that focus on the United States or European countries. This paper seeks to contribute to the debate in the region and, particularly, to the Mexican case, by looking at a variation of institutional trust/credibility as a determinant of crime reporting: reputation.

Data and Methodology

The data for this study came from Mexico’s National Survey of Victimization and Perception of Public Security (ENVIPE, in Spanish), published annually by Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI, in Spanish) from 2011 to 2019. The survey is conducted by INEGI on an annual basis, through face-to-face interviews in households selected by conglomerate sampling with statistical representativeness for each of the 32 states of Mexico. In total, this work utilizes around 270,000 survey entries, as the number of observations each year is close to 30,000.

For this study, only observations for "theft in the street, public transportation or ATM” were selected. This decision was taken for two reasons: First, these crimes are particularly relevant within the Mexican context, as they represent the most frequent offenses in the survey (47.3% of the total). The second relates to unbiasedness in the reporting process, as when using a victimization survey as the main source of analysis, the reporting of serious crimes tends to present significant biases and limitations that make them unreliable (Sozzo, 2003). The three types of theft are not cataloged as high-impact crimes according to the Mexican classification; therefore, one can expect that the reporting bias is less than that for serious crimes.

Observations in the database were weighted according to a crime factor. Weights adjusted to 5% were used, based on the crime factor of the ENVIPE for each year of the survey. The procedure was as follows: 5% of the highest values of the crime factor were adjusted to the value of the observation in the 95th percentile. The same was done with the lowest 5% of the values, adjusting them to the value of the observation in percentile 5. The average of these values was then obtained, and the new crime factor was divided by this average in order to obtain the weighting for each observation. Additionally, reports coming from urbanized regions are over-represented in the crime factor in comparison to those in rural areas where crime is less prevalent. The weights used for this overrepresentation are taken directly from INEGI’s victimization survey methodology in which, for each municipality and state, a factor is allocated considering both population density and urbanization statistics.

Variables related to reputation were grouped annually and lagged (differenced) by a year. This was done for three reasons. First, in year , the reputation of a prosecutor’s office in the state is not determined primarily by the people who reported crimes in the same year, but those who reported, for example, in . This helps to capture the reputation’s diffusion effect through time. Second, even though the survey asks for the specific month in which respondents were victims of a crime, this variable is not a reliable way of knowing the real month the person actually reported the crime at a MP office. The great number of missing values for the month of reporting is a consequence of people’s tendency to forget the exact month that they were victims of a crime (Dodge, 1981). Third, as the process of reporting a crime might take several months in Mexico because victims need to go repeatedly to the prosecutor’s office to ratify information and complete forms, among other processes, respondents may specify either when the process began or when it finished, without properly identifying the time of the crime reporting (Bergman et al., 2008). By grouping the observations in yearly counts, both reporting time mismatches become irrelevant.

In accordance with the crime reporting literature, the main hypothesis of this paper is that the good reputation of MP offices positively affects the decision of victims to report a crime. This is particularly important in the Mexican case as, in contrast to systems such as the one in the US, the prosecutors are the only entity that can judicially process a crime. Therefore, simply put, the better the reputation of the MP office, the more probable it is that a victim will report a crime.

In order to measure the treatment, efficacy, and fairness reputations of MP offices, five questions from the survey were selected, and responses from each year were aggregated for each of the 32 states. We incorporated these state-level measures as contextual variables as one individual’s opinion on the actions of the justice system and the police largely depends on the context in which these occurred. Simply put, the aggregated response regarding a state was assigned to an inhabitant to control for the heterogeneity of Mexican states. The underlying idea is that if an individual contemplates to report a crime in a state considered to be more secure than others, it will be more likely that his perception of the MP reputation will be different (perhaps better) than the one of a state considered to be more insecure.

Finally, two variables were created to measure good and bad reputations on separate scales: one for good reputation (only good opinions) and one for bad reputation (only very bad opinions). Median and mid-bad opinions were omitted. Only these two options were considered as, given that victims are required to go to the prosecutor’s office on various occasions, by only accounting for extreme opinions, we assume a person always received either good or poor treatment, omitting those who sometimes experienced good treatment and sometimes bad. For the perception of corruption, a single variable was maintained. Table 1 summarizes the nine variables that measure reputation.

Table 1.

Description of variables used to measure treatment, efficacy, and fairness reputations of MP offices

| Dimension | Survey question | Good reputation variable [% of surveyed in the State that answered…] | Bad reputation variable [% of surveyed in the State that answered…] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment reputation | How do you rate the treatment you received in the MP when you reported the crime? | (1) Received good treatment | (2) Received very bad treatment |

| How long did it take to process your report in the MP? | (3) Spent less than 1 h | (4) Spent more than 3 h | |

| Efficacy reputation | How effective do you consider the performance of the MP? | (5) Perceive the office as effective | (6) Perceive the office as not effective at all |

| Fairness reputation | How much trust does the MP inspire? | (7) Perceive MP as trustworthy | (8) Perceive MP as not trustworthy at all |

| In your opinion, can the MP be described as corrupt? | (9) Single variable (to avoid collinearity): | ||

| Perceive MP as corrupt | |||

Considering the three dimensions of reputation, the main hypotheses to be tested are the following:

H1 The treatment reputation of the prosecutor’s office is positively correlated with the probability of a victim reporting a crime to the office.

H2 The efficacy reputation of the prosecutor’s office is positively correlated with the probability of a victim reporting a crime to the office.

H3 The fairness reputation of the prosecutor’s office is positively correlated with the probability of a victim reporting a crime to the office.

To test the three hypotheses at the individual level, three logit models were created. In addition to the explanatory variables to measure the MP reputation explained above, three dummy variables were also included to measure personal opinions regarding confidence in the MP: trust in the MP office, opinion of its effectiveness, and perception of corruption. Several control variables were also incorporated into the models, motivated by the literature on crime reporting, and described in the following paragraphs.

In accordance with Goudriaan, Lynch and Nieuwbeerta (2004), and Greenberg and Beach (2004), the first set of control variables is related to crime characteristics such as: the amount lost as a consequence of the crime (in Mexican pesos, deflated to 2013 values); recognition of the criminal; physical harm; if the victim was accompanied during the crime; weapon used by the criminal; objects stolen by the offender (if the objects are protected by insurance, or would need a theft report in order to be replaced). In addition, based on works such as Hindelang and Gottfredson (1976), and Skogan (1984), a second set of control variables related to victim characteristics was used. This set includes victim’s sex; educational level; age; place of living (urban, semi-urban or rural); perception of security around the living place, and personal concerns on security-related issues. Finally, the variable of educational level is included as a proxy to control for the victim’s income as this is not included in the ENVIPE. Table 2 provides a description of all the variables included in the models.

Table 2.

Description of variables included in the logit models

| Variable | Values in database | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||||

| Crime report | 1 = Did report | 0 | 1 | 0.11 | |

| 0 = Did not report | |||||

| Explicative variables [all models] | |||||

| MP Treatment reputation | |||||

| (1) % of people in the area with excellent reviews of contact with the MP | 1–100 [Percentage of respondents in the State in the previous year who indicated they received excellent treatment] | 2.7 | 9.9 | 6.3 | 1.9 |

| (2) % of people in the area with very bad reviews of contact with the MP | 1–100 [Percentage of respondents in the State in the previous year who indicated they received very bad treatment] | 7.8 | 29.4 | 17.2 | 5 |

| (3) % of people in the area who spent less than 1 hour in the MP to report the crime | 1–100 [Percentage of respondents in the State in the previous year who indicated they spent less than 1 h] | 4.6 | 56.8 | 19.8 | 8.2 |

| (4) % of people in the area who spent 3 or more hours in the MP to report the crime | 1–100 [Percentage of respondents in the State in the previous year who indicated they spent 3 or more hours] | 9.5 | 72.7 | 33.4 | 13.4 |

| MP Efficacy reputation | |||||

| (5) % of people in the area who perceive the office as very efficient | 1–100 [Percentage of respondents in the State in the previous year who indicated they perceive the office as very effective] | 0.4 | 17.6 | 7.5 | 3.5 |

| (6) % of people in the area who perceive the office as very inefficient | 1–100 [Percentage of respondents in the State in the previous year who indicated they perceive the office as very ineffective] | 7.5 | 41.1 | 20.9 | 6.4 |

| Personal opinion Do you consider the performance of the MP as effective? | 0 = The MP is not effective | 0 | 1 | 0.41 | |

| 1 = The MP is effective | |||||

| MP Fairness reputation | |||||

| (7) % of people in the area who do trust the MP | 1–100 [Percentage of respondents in the State in the previous year who indicated they perceive the MP as very trustworthy] | 1.5 | 21.3 | 9.5 | 4.2 |

| (8) % of people in the area who do not trust at all the MP | 1–100 [Percentage of respondents in the State in the previous year who indicated they perceive the MP as very untrustworthy] | 12.4 | 48.1 | 25 | 6.8 |

| Personal opinion Do you trust the MP? | 0 = Do not trust the MP | 0 | 1 | 0.39 | |

| 1 = Trust the MP | |||||

| (9) % of people in the area who perceive the MP as corrupt | 1–100 [Percentage of respondents in the State in the previous year who indicated they perceive the MP as corrupt] | 56.6 | 94.9 | 76.1 | 7.7 |

| Personal opinion In your opinion, can the MP be described as corrupt? | 0 = The MP is not corrupt | 0 | 1 | 0.75 | |

| 1 = The MP is corrupt | |||||

| Characteristics of the crime [model 2 and 3] | |||||

| Amount lost as a consequence of the crime | Five groups of reported loss in Mexican pesos, deflected to 2013 values: | ||||

| No loss (base) | |||||

| $1 to 5,000 | |||||

| $5,001 to 10,000 | |||||

| $10,001 to 50,000 | |||||

| More than $ 50,000 | |||||

| Would recognize criminal(s) | 0 = Would not recognize | ||||

| 1 = Would recognize | |||||

| The criminal used violence or physically hurt the victim | 0 = Did not suffer injury | ||||

| 1 = Suffered injury | |||||

| The victim was accompanied | 0 = Was alone | ||||

| 1 = Was accompanied | |||||

| Weapon used by the criminal | Grouped by type of weapon: | ||||

| No weapon (base) | |||||

| Other weapon (knife, tube) | |||||

| Firearm | |||||

| The offender stole… | 0 = Was not stolen | ||||

| (a) Cellphone | 1 = Was stolen | ||||

| (b) Official documents | |||||

| (c) Electronic equipment | |||||

| (d) Jewelry or watch | |||||

| Victim’s characteristics [model 3] | |||||

| Sex | 0 = Woman (base) | ||||

| 1 = Man | |||||

| Educational level | Grouped by educational level: | ||||

| Up to primary school (base) | |||||

| Secondary school | |||||

| High school | |||||

| Undergraduate or graduate | |||||

| Age group | Grouped by 10-year intervals | ||||

| Less than 20 years old (base) | |||||

| 20–29 years old | |||||

| 30–39 years old | |||||

| … | |||||

| More than 80 years old | |||||

| Place of living | Grouped by domain: | ||||

| Urban area (base) | |||||

| Rural area | |||||

| Semi-urban area | |||||

| Feeling of security around the living place | |||||

| Feels safe in his/her home | |||||

| Feels safe in the street | 0 = Feels unsafe | ||||

| 1 = Feels safe | |||||

| Feels safe in the municipality | |||||

| Personal concerns | |||||

| Is concerned about insecurity | |||||

| Is concerned about corruption | |||||

| Is concerned about impunity | |||||

| Is concerned that might be mugged before the end of the year | 0 = Not concerned | ||||

| 1 = Concerned | |||||

| Is concerned that might be hurt before the end of the year | |||||

| Is concerned that might be extorted or kidnapped before the end of the year | |||||

| Survey year | |||||

| Dummy variable for each year | Seven dummy variables |

Results

Three nested logit models were estimated, results are presented in Table 3. The first, with a sample size of 21,915 observations, only includes the nine MP reputation variables and the three personal opinion variables. The second, with 18,556 observations, incorporates characteristics of the crime to model 1, while the third, comprising 17,801 observations, additionally includes variables related to the characteristics of the victim. Regarding the reputation related to the treatment received by the victims, results suggest that more time spent in the MP office is negatively related to the probability of reporting a crime. The rest of the variables related to treatment do not seem to be significant. These results hold for the three models.

Table 3.

Summary of results from the logit regression models

| B | Model 1 | B | Model 2 | B | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE B | eB | SE B | eB | SE B | eB | ||||

| MP treatment reputation | |||||||||

| (1) Received good treatment | − .006 | 0.006 | 0.99 | − .001 | 0.007 | 1 | 0 | 0.007 | 1 |

| (2) Received very bad treatment | − .010 | 0.004 | 0.99 | − .006 | 0.005 | 0.99 | − .007 | 0.005 | 0.99 |

| (3) Spent less than 1 h | − .002 | 0.004 | 1 | − .004 | 0.005 | 1 | 0 | 0.005 | 1 |

| (4) Spent more than 3 h | − .009* | 0.003 | 0.99 | − .011* | 0.003 | 0.99 | − .010* | 0.004 | 0.99 |

| MP efficacy reputation | |||||||||

| (5) Perceive the MP as effective | − .043 | 0.018 | 0.96 | − .045 | 0.021 | 0.96 | − .051 | 0.022 | 0.95 |

| (6) Perceive the MP as not effective at all | 0.003 | 0.013 | 1 | 0.023 | 0.015 | 1.02 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 1.03 |

| Personal opinion MP is effective | − .045 | 0.053 | 0.96 | − .005 | 0.061 | 0.99 | − .027 | 0.062 | 0.97 |

| MP fairness reputation | |||||||||

| (7) Perceive MP as trustworthy | 0.02 | 0.017 | 1.02 | 0.022 | 0.019 | 1.02 | 0.025 | 0.02 | 1.03 |

| (8) Perceive MP as not trustworthy at all | − .019 | 0.013 | 0.98 | − .044* | 0.015 | 0.96 | − .047* | 0.015 | 0.95 |

| Personal opinion MP is trustworthy | 0.105 | 0.053 | 1.11 | 0.133 | 0.061 | 1.14 | 0.148 | 0.062 | 1.16 |

| (9) Perceive MP as corrupt | − .011 | 0.005 | 0.99 | − .010 | 0.006 | 0.99 | − .012 | 0.006 | 0.99 |

| Personal opinion MP is corrupt | 0.047 | 0.054 | 1.05 | 0.08 | 0.063 | 1.08 | 0.059 | 0.065 | 1.06 |

| Characteristics of the crime | |||||||||

| Amount lost (base No loss) | |||||||||

| $1 to 5000 | − .127 | 0.081 | 0.88 | − .128 | 0.082 | 0.88 | |||

| $5001 to 10,000 | .768* | 0.098 | 2.15 | .709* | 0.1 | 2.03 | |||

| $10,001 to 50,000 | 1.250* | 0.105 | 3.49 | 1.188* | 0.108 | 3.28 | |||

| More than $ 50,000 | 2.021* | 0.204 | 7.55 | 1.956* | 0.209 | 7.07 | |||

| Would recognize offender(s) | .656* | 0.048 | 1.93 | .638* | 0.049 | 1.89 | |||

| Offender used violence | .566* | 0.052 | 1.76 | .594* | 0.054 | 1.81 | |||

| The victim was accompanied | .228* | 0.049 | 1.26 | .218* | 0.05 | 1.24 | |||

| Weapon used (base no weapon) | |||||||||

| Other weapon | .190* | 0.068 | 1.21 | .196* | 0.07 | 1.22 | |||

| Firearm | .465* | 0.065 | 1.59 | .484* | 0.067 | 1.62 | |||

| The offender stole cellphone | 0.068 | 0.05 | 1.07 | 0.057 | 0.052 | 1.06 | |||

| The offender stole official documents | .783* | 0.065 | 2.19 | .759* | 0.067 | 2.14 | |||

| The offender stole electronic equip | 0.192 | 0.096 | 1.21 | 0.15 | 0.099 | 1.16 | |||

| The offender stole jewelry or watch | − .141 | 0.075 | 0.87 | − .146 | 0.076 | 0.86 | |||

| Victim’s characteristics | |||||||||

| Sex (base woman) | − .016 | 0.049 | 0.98 | ||||||

| Education (base Up to primary school) | |||||||||

| Secondary school | 0.2 | 0.103 | 1.22 | ||||||

| High school | .387* | 0.101 | 1.47 | ||||||

| .575* | 0.099 | 1.78 | |||||||

| Age group (base less than 20 years old) | |||||||||

| 20–29 years old | 0.106 | 0.106 | 1.11 | ||||||

| 30–39 years old | 0.182 | 0.11 | 1.2 | ||||||

| 40–49 years old | 0.254 | 0.116 | 1.29 | ||||||

| 50–59 years old | 0.081 | 0.135 | 1.08 | ||||||

| 60–69 years old | 0.138 | 0.179 | 1.15 | ||||||

| 70–79 years old | 0.183 | 0.367 | 1.2 | ||||||

| More than 80 years old | 0.782 | 0.582 | 2.19 | ||||||

| Place of living (base urban) | |||||||||

| Rural area | 0.081 | 0.1 | 1.08 | ||||||

| Semi-urban area | .240* | 0.067 | 1.27 | ||||||

| Feeling of security around the living place | |||||||||

| Safe in home | 0.086 | 0.056 | 1.09 | ||||||

| Safe in the street | − .153 | 0.076 | 0.86 | ||||||

| Safe in the municipality | .178* | 0.06 | 1.19 | ||||||

| Personal concerns | |||||||||

| Insecurity | − .053 | 0.055 | 0.95 | ||||||

| Corruption | 0.006 | 0.051 | 1.01 | ||||||

| Impunity | 0.138 | 0.058 | 1.15 | ||||||

| Might be mugged | − .221 | 0.1 | 0.8 | ||||||

| Might be hurt | 0.018 | 0.065 | 1.02 | ||||||

| Might be extorted or kidnapped | − .026 | 0.055 | 0.97 | ||||||

| Survey year | |||||||||

| 2012 | − .082 | 0.092 | 0.92 | − .111 | 0.11 | 0.9 | − .114 | 0.122 | 0.89 |

| 2013 | 0.039 | 0.087 | 1.04 | 0.203 | 0.1 | 1.23 | 0.194 | 0.112 | 1.21 |

| 2014 | − .251* | 0.091 | 0.78 | − .180 | 0.103 | 0.83 | − .233 | 0.114 | 0.79 |

| 2015 | 0.099 | 0.089 | 1.1 | 0.164 | 0.102 | 1.18 | 0.16 | 0.112 | 1.17 |

| 2016 | − .086 | 0.096 | 0.92 | − .035 | 0.109 | 0.97 | − .046 | 0.119 | 0.96 |

| 2017 | − .219 | 0.099 | 0.8 | − .230 | 0.113 | 0.79 | − .220 | 0.123 | 0.8 |

| 2018 | 0.096 | 0.081 | 1.1 | 0.075 | 0.094 | 1.08 | 0.085 | 0.095 | 1.09 |

| Constant | 0.023 | 0.39 | 1.02 | − 1.067 | 0.457 | 0.34 | − 1.417* | 0.505 | 0.24 |

| χ2 | 253 | 1511 | 1533 | ||||||

| df | 19 | 32 | 55 | ||||||

| N | 21,915 | 18,556 | 17,801 | ||||||

| Pseudo r2 | 0.0152 | 0. 1083 | 0.1142 | ||||||

*Denotes significance at a 1% level, answers were coded as 0 = Did not report; 1 = Report

Regarding the crime characteristics, the amount lost as a consequence of a crime is the variable that most impacts a victim’s decision to report. For instance, robberies with a limited loss (less than $5,000 Mexican pesos (MXN), ~ 250 USD) are unlikely to be reported as the results for models 2 and 3 suggest there is no significant change in the probability of reporting when compared to the no loss case. However, as the amount increases, from $5,000 MXN or above, so does the probability of reporting. When the amount reaches the maximum level, around $50,000 MXN, ~ 2,500 USD, it becomes seven times more likely that the crime will be reported compared to the no loss case. Simply put, these results imply that economic loss remains one of the main determinants of the decision to report a crime.

On the other hand, the severity of a crime also increases the probability of crime reporting. From both models 2 and 3, a significant increase in the probability of reporting can be seen when the crime was committed using a firearm or other weapons when compared to cases where no weapon was used. Furthermore, if the victim was subject to violence, was accompanied, or could recognize the offender, the probability of reporting a crime also increases. This boosts crime reporting as injuries or external confirmation may be considered evidence that helps to build a stronger case against the offender. When analyzed by type of items stolen, only the theft of an official document increases the probability of reporting a crime. In fact, this almost doubles the chances of reporting a robbery. Other items do not appear to be significant to the reporting decision. This can be explained by the need to invalidate a stolen official document, for example an ID or passport, to avoid future misuse.

For the set of variables that includes the victim’s characteristics, sex seem to be irrelevant as a factor for reporting, with no difference in crime reporting found between women and men. This is also true for age groups. However, a differentiated effect between urban and semi-urban areas in the probability of reporting a crime is found. Additionally, higher education levels seem to increase the probability of reporting a crime, particularly when comparing the High school and the Undergraduate or Graduate levels to the base case (up to primary school). Finally, a feeling of safety in the municipality appears to increase the probability of reporting a crime, mostly sustained by the confidence that there will not be any retaliation from the victimizer, while no other personal concerns seem to be significant in the decision to report a crime.

None of the variables that measure reputation related with efficacy were significant, and only one variable associated to fairness reputation (the victim’s personal opinion of the MP’s trustworthiness) was significant and had a negative effect for Models 2 and 3. Simply put, if the victim perceives the MP as untrustworthy, the probability of reporting the crime decreases. It is worth noting that Model 1 has a very limited predictive power (pseudo r2 = 0.015). This means that reputation variables cannot explain, on their own, a victim’s decision to report a crime to the prosecutor’s office. In Models 2 and 3, when including control variables of crime and victim characteristics, the predictive power of the regression increases as the pseudo r2 approximates 0.11 in both cases (Table 3).

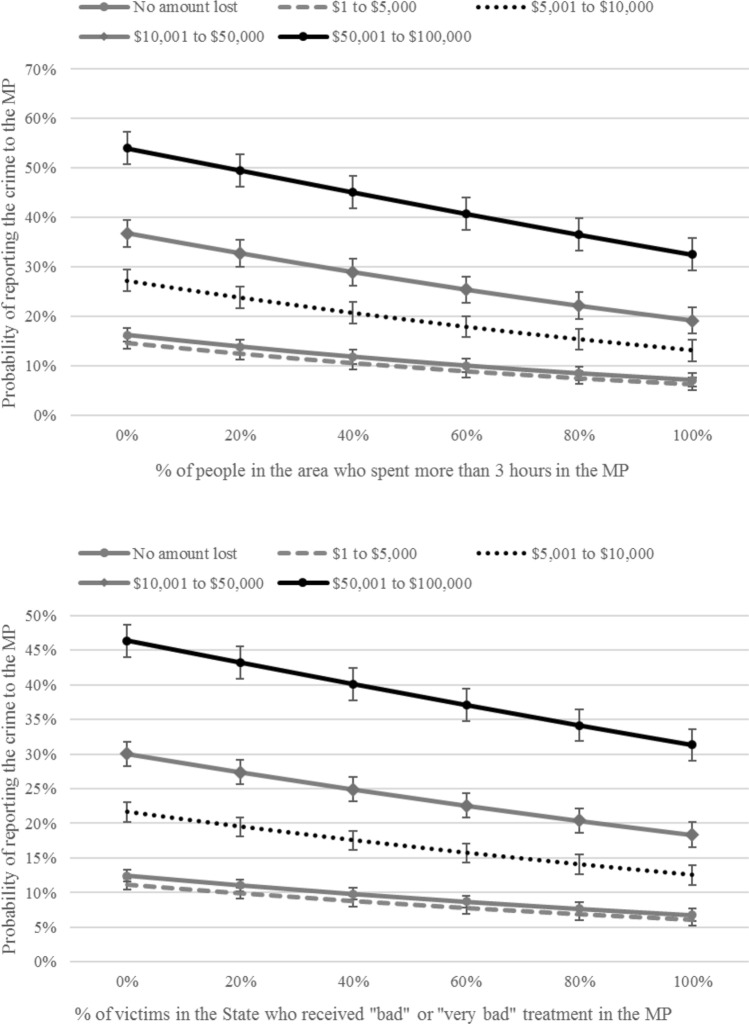

Consistent with past studies, results suggest that the most important determinants of theft crime reporting are those related to the seriousness of the crime, such as amount lost, violence, and/or use of firearms (Greenberg & Beach, 2004; Kury et al., 1999; Schneider, Burcart & Wilson, 1976). Even when some variables of the MP’s reputation are significant, these alone cannot explain the decision of a victim to report a crime. Nonetheless, when combining the severity of a crime with the significant variables of reputation, the effects of changes in the MP’s reputation on the probability of crime reporting is meaningful. This is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Probability of crime reporting for the two significant reputation components, according to Model 3, disaggregated by levels of amount lost.

Source: own elaboration, logit margins according to Model 3, amounts expressed in Mexican pesos MXN

Regarding the treatment reputation, it is interesting to note that the distinction between good and very bad treatment is not relevant in terms of the probability of reporting a crime. This might be due to the particular characteristics of the MP offices in Mexico: attention is usually bad, there are long waiting periods, revictimization is expected, and staff will frequently try to persuade victims not to report a crime in order to reduce the officially reported crime rate of the area (Baranda, 2018). Hypothesis H1 is, thus, found to be partially validated by the time component of the treatment received, but not by the experience alone.

In this regard, the results of the treatment reputation are consistent with findings from past studies, which have shown that inconveniences, like high costs of transportation and parking, or excessive time lost at the office, have a negative impact on a victim’s reporting decision (Greenberg & Ruback, 2012). Citizens expect the criminal justice system to deal with a crime without causing undue inconvenience or embarrassment (Spelman & Brown, 1981). Thus, if the prosecutor’s office has not been able to do so in the past, a victim might decide to avoid the trouble of involving the authorities. Simply put, the greater the prevalence of bad opinions in the area, the lower the probability of a victim reporting a crime. The Mexican case seems to reflect this, as citizens rarely expect to receive good treatment at MP offices; it may, therefore, be understandable that their reporting decision depends more on the time spent on the reporting process than on the quality of treatment.

Efficiency and corruption perceptions do not appear to have an effect on a victim’s decision to report a crime. Following a similar logic to the previous dimension, it would seem that neither the effectiveness of the MP office nor the perception of their levels of corruption are relevant in the reporting decision. This can be explained by generalized and high rates of impunity prevalent in the judicial system. A citizen might report a crime independently of the MP’s efficacy and fairness reputation (or the lack procedural justice, i.e., equality of treatment), in order to claim from insurance, for example, rather than to pursue justice for the crime they suffered. Nonetheless, personal opinions on the trustworthiness of the MP, do affect the probability of reporting, particularly, in the extreme case of untrustworthiness. If the MP is perceived as not trustworthy at all, the probability of reporting crime decreases. In this case, hypothesis H3 is partially validated by a negative perspective of trustworthiness. As explained above, the fairness reputation is the most difficult for a citizen to assess as there are incentives to lie about one’s experience in the MP offices (particularly in cases of unequal treatment), or it might be skewed depending on the outcome of the process. Citizens cannot be sure that the prosecutor’s office’s reputation is indeed real, and thus, when deciding whether or not to involve the authorities, they seem to rely more on their own idea of the trustworthiness of the office than on the general opinion.

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Past studies have shown that social influence, partly determined by levels of procedural justice perceived in treatment, is an important factor when a victim is deciding whether to report a crime to the police. Direct advice (“I think you should call the police”) and arguments (“The police are likely to apprehend him”) from family, acquaintances, or bystanders, are good predictors of a victim’s decision to report, as they can increase by up to 12-fold the probability of crime reporting (Greenberg & Beach, 2004; Greenberg & Ruback, 2012; Spelman & Brown, 1981). However, this influence is not always present as not all victims receive direct advice or arguments in favor of involving the authorities in an investigation. The effect of the indirect social influence, namely reputation, has not been directly and thoroughly studied regarding the question of crime reporting.

This article explored the influence of institutional reputation on crime reporting decisions. From the three reputation dimensions described in the study’s framework (treatment, efficacy, and fairness) only one component related to the treatment dimension, time spent in the prosecutor’s office, and one related to the fairness dimension, perception of untrustworthiness, were negatively related to the probability of reporting a crime. Few reputation variables were significant while control variables related to the crime circumstances were better predictors of a victim’s decision to report a crime (mainly the amount lost and the theft of official documents).

The finding related to the amount of time spent in the reporting process is relevant for the design and implementation of public policy regarding tools such as online crime reporting systems (Iriberri, Leroy & Garrett, 2006) or strategies to improve mechanisms that provide efficient attention to the public. On the other hand, building trust involves enhancing policing strategies, from the number of officers and their distribution, to improving police-community relations, and the reduction of impunity (Block, 1973; Skogan, 1976, 1984; Warner, 2007). The direct negative effect of not dealing with these, is a low level of crime reporting, resulting in the police working blindly or using their own sources of information which do not necessarily respond to the “true” behavior of crime. This is particularly critical in regions with high victimization and limited trust in the police, related to the lack of adequate procedural justice in situations of contact with the public, such as in Latin America (Dammert, 2009).

Interestingly, we found that regardless of the reputation of the MP office in Mexico, the probability of reporting a crime will be very low unless the crime was especially costly. The reason may rest in the regional situation, particularly in Mexico, that is somewhat reminiscent of the spirit of legal cynicism (incompetence, illegitimacy, and lack of responsiveness of the criminal justice system) described by Kirk and Papachristos (2011) to explain the low rates of reporting in poor and/or minority communities.

The results are not without their limitations, and we acknowledge that the characteristics of the Mexican justice system (legalist, ineffective, and unkind to victims who decide to report a crime) might impact the crime reporting decision. It is possible that in other countries, other components of efficacy and fairness reputations do impact a victim’s decision to report a crime, while in Mexico the effect is null due to the widespread impunity and corruption that generally characterize state prosecutors’ offices.

The link between impunity/corruption and institutional reputation, as a category of public administration, has almost not been studied in the literature on crime reporting in Latin America and may be key to any public policy in matters of criminal justice. Most literature in the region has focused on processes of revictimization, evidence filters for the report to be accepted, and population distrust as mechanisms to explain low regional reporting. However, as has been seen, distrust, coupled with the slowness of procedures, influence the decision to report. This explains why the true predictor of reporting is the type of crime, as well as its characteristics and seriousness, or the need for a report for an insurance payout.

We recognize the importance of pursuing this course of research in future studies in order to compare other countries and the characteristics of their judicial systems. New surveys of victimization that include these types of variables, will allow for comparative work on a regional level, given that almost the entire region shares the challenge of low reporting. An ideal future study, in terms of institutional reputation of the justice system, is to disaggregate the variable of perception of the prosecutors’ equality to understand more precisely, the cause of this distrust. This would be particularly interesting for respondents with no previous contact with prosecutors and where social influence operates, but where procedural justice does not work as a mechanism of explanation. This information would also be useful for the development of any public policy that aims to improve criminal reporting in the region, based on changing the treatment of the population by the authorities.

Funding

No funding was received.

Data Availability

Upon request.

Code Availability

Upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

References

- Allen H. Bystander intervention and helping behavior on the subway. Beyond the laboratory: Field research in social psychology. McGraw-Hill; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez G, Fuentes C. Denuncias por actos de violencia policial en Chile 1990-2004. Flacso; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Balán M. Competition by denunciation: The political dynamics of corruption scandals in Argentina and Chile. Comparative Politics. 2011;43(4):459–478. doi: 10.5129/001041511796301597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baranda, A. (2018). Exhiben deficiencias en agencias del MP, Refoma. Retrieved January 24, from http://www.reforma.com/aplicaciones/articulo/default.aspx?id=1307013&v=4

- Baumer EP, Lauritsen JL. Reporting crime to the police, 1973–2005: A multivariate analysis of long-term trends in the National Crime Survey (NCS) and National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) Criminology. 2010;48(1):131–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2010.00182.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benavente H, Cortés E. Delitos y sus denuncias. La cifra negra de la criminalidad en Chile y sus determinantes. Universidad de Chile; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman M, Sarsfield R, Fondevila G. Encuesta de victimización y eficacia institucional. CIDE; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L. Interpersonal influence and the reporting of a crime. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1979;5(1):32–35. doi: 10.1177/014616727900500106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birgin H, Gherardi N. Violencia familiar: Acceso a la justicia y obstáculos para denunciar. In: Femenías M, Aponte Sánchez E, editors. Femenías Articulaciones sobre la violencia contra las mujeres. UNLP; 2008. pp. 239–266. [Google Scholar]

- Block R. Why notify the police. The victim's decision to notify the police of an assault. Criminology. 1973;11(4):555–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1974.tb00614.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boiraa S, Carbajosa P, Méndez R. Miedo, conformidad y silencio. La violencia en las relaciones de pareja en áreas rurales de Ecuador. Psychosocial Intervention. 2016;25(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psi.2015.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford B, Murphy K, Jackson J. Officers as mirrors: Policing, procedural justice and the (re)production of social identity. British Journal of Criminology. 2014;54:527–550. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azu021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckhout R. Eyewitness testimony. Scientific American. 1974;231(6):23–31. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1274-23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter D. Reputation and power: Organizational image and pharmaceutical regulation at the FDA. Princeton University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll CE. Corporate reputation and the multi-disciplinary field of communication. In: Carroll CE, editor. The handbook of communication and corporate reputation. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2013. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Casas Becerra L, González-Ballesteros A. Delitos sexuales y Lesiones. La Violencia de Género en la Reforma Procesal Penal en Chile. Universidad Diego Portales; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S. Bureau of justice statistics bulletin: Criminal victimization, 2005. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dammert L. Chile: ¿el país más seguro de América Latina? Flacso; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dammert L, Zúñiga L. Seguridad y violencia: desafíos para la ciudadanía. Flacso; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dammert L, Salazar F, Montt C, González P. Crimen e inseguridad: indicadores para las Américas. Flacso; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Darley J, Latane B. Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1968;8:377–383. doi: 10.1037/h0025589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, R. (1981). The Washington, D.C., recall study. In: Lehnen, R. & Skogan, W. (Eds.). The National Crime Survey: Working Papers, Volume I: Current and Historical Perspectives, U.S. Department of Justice

- Duce MA. Análisis de los datos criminales: Factores determinantes de la probabilidad de denunciar un delito. In: Begoña PC, Pilar AM, Victor LS, editors. Estructura de la comunicación en entornos digitales. Egregius; 2018. pp. 146–165. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza-Barrera A. Factores que dificultan el recaudo de medios probatorios en las denuncias de violencia familiar tramitadas en las fiscalías de familia del distrito fiscal de Moquegua. Revista Ciencia y Tecnología. 2016;2(3):68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Feins JD, Peterson J, Rovetch E. Partnerships for neighborhood crime prevention. US Department of Justice National Institute of Justice; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira Amendola M. Analisando e (des)construindo conceitos: Pensando as falsas denúncias de abuso sexual. Estudos e Pesquisas Em Psicologia. 2009;9(1):196–215. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun CJ. Reputation. Harvard Business School Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fondevila G. Police efficiency and management: Citizen confidence and satisfaction. Mexican Law Review. 2008;1(1):109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo J. Police and public opinion-an analysis of victimization and attitude data from 13 American cities. Criminal Justice. 1977;1971:75. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson MR, Gottfredson DM. Decision making in criminal justice: Toward the rational exercise of discretion. Springer Science & Business Media; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Goudriaan H. Reporting crime: Effects of social context on the decision of victims to notify the police. Universal Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Goudriaan H, Lynch JP, Nieuwbeerta P. Reporting to the police in western nations: A theoretical analysis of the effects of social context. Justice Quarterly. 2004;21(4):933–969. doi: 10.1080/07418820400096041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goudriaan H, Wittebrood K, Nieuwbeerta P. Neighbourhood characteristics and reporting crime: Effects of social cohesion, confidence in police effectiveness and socio-economic disadvantage. British Journal of Criminology. 2006;46(4):719–742. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azi096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MS, Beach S. Property crime victims' decision to notify the police: social, cognitive, and affective determinants. Law and Human Behavior. 2004;28(2):177–186. doi: 10.1023/B:LAHU.0000022321.19983.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MS, Ruback RB. After the crime: Victim decision making. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, T.C., & Rennison, C. (2003). Reporting Crime to the Police, 1992–2000. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

- Hindelang MJ, Gottfredson M. The victim's decision not to invoke the criminal justice process. In: McDonald WF, editor. Criminal justice and the victim. Sage; 1976. pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hohl K, Bradford B, Stanko E. Influencing trust and confidence in the London metropolitan police. British Journal of Criminology. 2010;50:491–513. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azq005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Incháustegui Romero T, Barajas L, de la Paz M. Violencia feminicida en México: Características, tendencias y nuevas expresiones en las entidades federativas, 1985–2010. Cámara de Diputados; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Survey: Encuesta Nacional de Victimización y Percepción sobre Seguridad Pública (ENVIPE) for years 2011–2019. Retrieved March 25, 2020, from https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/envipe/2019/

- Iriberri, A., Leroy, G., & Garrett, N. (2006). Reporting on-campus crime online: User intention to use. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 4: 82a. IEEE.

- Jackson J, Bradford B, Hough M, Myhill A, Quinton P, Tyler T. Why do people comply with the law? Legitimacy and the influence of legal institutions. British Journal of Criminology. 2012;52:1051–1071. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azs032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Vargas M, Casas-Casas A. Contar o no contar: Un análisis de la incidencia de las denuncias en los desenlaces de casos de secuestro extorsivo en Colombia. Papel Político. 2012;17(1):119–158. [Google Scholar]

- Kääriäinen J, Sirén R. Trust in the police, generalized trust and reporting crime. European Journal of Criminology. 2011;8(1):65–81. doi: 10.1177/1477370810376562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk DS, Papachristos AV. Cultural mechanisms and the persistence of neighborhood violence. American Journal of Sociology. 2011;116(4):1190–1233. doi: 10.1086/655754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruttschnitt C, Carbone-Lopez K. Customer satisfaction: Crime victims’ willingness to call the police. U.S. Police Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kury H, Teske R, Wurger M. Reporting of crime to the police in the federal republic of Germany: A comparison of the old and the new lands. Justice Quarterly. 1999;16:123–151. doi: 10.1080/07418829900094081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos M, Dammert L. La Seguridad Ciudadana El problema principal de América Latina. Latinobarómetro; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Latané B, Darley JM. The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn't he help? Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Lind E, Tyler T. The social psychology of procedural justice. Plenum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Londoño J, Guerrero R, Couttolene B, Cano I. Violencia en América Latina: Epidemiología y costos. In: Guerrero R, Gaviria A, Londoño J, editors. Asalto al desarrollo: Violencia en América Latina. BID; 2002. pp. 11–57. [Google Scholar]

- López-Valdez A. La denuncia de delitos sexuales. Camino doblemente victimizante: Una mirada desde las víctimas de violencia sexual. Revista De Trabajo Social. 2014;7:71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Mancera A. Factores socioeconómicos y demográficos de distintas categorías de delitos en Colombia. Observatorio De La Economía Latinoamericana. 2008;104:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mazerolle L, Antrobus E, Bennett S, Tyler TR. Shaping citizen perceptions of police legitimacy: A randomized field trial of procedural justice. Criminology. 2013;51(1):33–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2012.00289.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazerolle L, Bennett S, Antrobus E, Eggins L. Procedural justice, routine encounters and citizen perceptions of police: Main findings from the Queensland community engagement trial. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2012;8:343–367. doi: 10.1007/s11292-012-9160-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz PM, Mills J. Effects of arousal and information about its source upon attitude change. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1971;7(6):561–570. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(71)90019-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K. Does procedural justice matter to youth? Comparing adults’ and youths’ willingness to collaborate with police. Policing & Society. 2015;25:53–76. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2013.802786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, Barkworth J. Victim willingness to report crime to police: Does procedural justice or outcome matter most? Victims and Offenders. 2014;9:178–204. doi: 10.1080/15564886.2013.872744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, Cherney A. Understanding cooperation with police in a diverse society. British Journal of Criminology. 2012;52:181–201. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azr065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, Mazerolle L. Policing immigrants: Using a randomized control trial of procedural justice policing to promote trust and cooperation. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 2018;51:3–22. doi: 10.1177/0004865816673691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, Mazerolle L, Bennett S. Promoting trust in police: Findings from a randomised experimental field trial of procedural justice policing. Policing and Society. 2014;24:405–424. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2013.862246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, Sargeant E, Cherney A. Procedural justice, police performance and cooperation with police: Does social identity matter? European Journal of Criminology. 2015;12:719–738. doi: 10.1177/1477370815587766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newburn T. Understanding and preventing police corruption: Lessons from the literature. Police research series, paper 110. Home Office; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nix J. Do the police believe that legitimacy promotes cooperation from the public? Crime & Delinquency. 2017;63:951–975. doi: 10.1177/0011128715597696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Morales V, Vélez Salas D, Rivas Rodríguez F, Vélez Salas M. Evolución de la extorsión en México: Un análisis estadístico regional (2012–2013) Revista Mexicana De Opinión Pública. 2015;18:112–135. doi: 10.1016/S1870-7300(15)71363-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quinteros D. Delitos del espacio público y el problema de la “cifra negra”: Una aproximación a la no-denuncia en Chile. Política Criminal. 2014;9(18):691–712. doi: 10.4067/S0718-33992014000200012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rand M, Catalano S. Criminal victimization. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin; 2007. p. 219413. [Google Scholar]

- Rengifo A, Slocum L, Chillar V. From impressions to intentions: Direct and indirect effects of police contact on willingness to report crimes to law enforcement. Journal of Research in Crime & Delinquency. 2019;56:412–450. doi: 10.1177/0022427818817338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riger S. Reactions to crime: Impacts of crime: On women. Sage Criminal Justice System Annuals; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Roebuck JB, Barker T. A typology of police corruption. Social Problems. 1974;21(3):423–437. doi: 10.2307/799909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal AM. Thirty-eight witnesses: The Kitty Genovese case. University of California Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Ruback RB, Greenberg MS, Westcott DR. Social influence and crime-victim decision making. Journal of Social Issues. 1984;40(1):51–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1984.tb01082.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schnebly SM. The influence of community-oriented policing on crime-reporting behavior. Justice Quarterly. 2008;25(2):223–251. doi: 10.1080/07418820802025009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider AL, Burcart JM, Wilson LA., II . The role of attitudes in the decision to report crimes to the police. In: McDonald WF, editor. Criminal justice and the victim. 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra J, Bermúdez M, Buela-Casal G, Salinas J, Monge F. Variables asociadas a la experiencia de abuso en la pareja y su denuncia en una muestra de mujeres. Universitas Psychologica. 2014;13(1):1–16. doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-1.vaea. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skogan WG. Citizen reporting of crime some national panel data. Criminology. 1976;13(4):535–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1976.tb00685.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skogan WG. Reporting crime to the police: The status of world research. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1984;21:113–137. doi: 10.1177/0022427884021002003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skogan W, Frydl K. Fairness and effectiveness in policing: The evidence. National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo Barrios V, González Rubio A. Análisis de seguimiento por denuncias de presuntos actos sexuales abusivos cometidos contra niños, niñas y adolescentes. Universitas Psychologica. 2006;5(2):397–418. [Google Scholar]

- Sozzo M. ¿Contando el delito? Análisis crítico y comparativo de las encuestas de victimización en Argentina. Universidad Nacional del Litoral; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spelman W, Brown DK. Calling the Police: Citizen reporting of serious crime. Police Executive Research Forum; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Sunshine J, Tyler T. The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law and Society Review. 2003;37:513–547. doi: 10.1111/1540-5893.3703002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarling R, Morris K. Reporting crime to the police. The British Journal of Criminology. 2010;50(3):474–490. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azq011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut J, Walker L. Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Erlbaum Associates; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Tilker HA. Socially responsible behavior as a function of observer responsibility and victim feedback. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1970;14(2):95–100. doi: 10.1037/h0028773. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N, Allison CJ. Comparing stalking victimization from legal and victim perspectives. Violence and Victims. 2000;15(1):7–22. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.15.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler T. Why people obey the law. Yale University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler T, Blader SL. Cooperation in groups: Procedural justice, social identity, and behavioral engagement. Psychology Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler T, Fagan J. Legitimacy and cooperation: Why do people help the police fight crime in their communities? Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law. 2008;6:231–275. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler T, Huo Y. Trust in the Law: Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts through. Russell Sage Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vilalta, C. Fondevila, G., and Massa, R. (2022). The Impact of Anti-COVID-19 Measures on Mexico City Criminal Reports, Deviant Behavior.

- Vilalta C, Fondevila G. La victimización de empresas en México. Gestión y Política Pública. 2018;XXVII(2):501–540. [Google Scholar]

- Vilalta C, Fondevila G. Perceived police corruption and fear of crime. Mexican Studies. 2020;36(3):425–450. doi: 10.1525/msem.2020.36.3.425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD. Directly intervene or call the authorities? A study of forms of neighborhood social control within a social disorganization framework. Criminology. 2007;45(1):99–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2007.00073.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe S, Nix J, Kaminski R, Rojek J. Is the effect of procedural justice on police legitimacy invariant? Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2016;32:253–282. doi: 10.1007/s10940-015-9263-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zakula B. La cifra oscura y las razones de la no denuncia en México. UNODC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zepeda Lecuona G. Crimen sin castigo: Procuración de justicia penal y ministerio público en México. Fondo de Cultura Económica; 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Upon request.

Upon request.