Abstract

To develop a serological diagnosis of invasive candidiasis based on detection of circulating secreted aspartyl proteinase (SAP) antigen of Candida albicans, three different enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were compared. The first was a standard ELISA to detect anti-SAP antibodies, and the others were an antigen capture ELISA and an inhibition ELISA to detect circulating SAP antigen with monoclonal antibody (MAb) CAP1, which is highly specific for SAP. These tests were applied to 33 serum samples retrospectively selected from 33 patients with mycologically and/or serologically proven invasive candidiasis caused by C. albicans. Serum samples from 12 patients with aspergillosis and serum samples from 13 healthy individuals were also included. The sensitivities and specificities were 69.7 and 76.0% for the standard ELISA and 93.9 and 92.0% for the antigen capture ELISA, respectively. However, these values reached 93.9 and 96.0%, respectively, for the inhibition ELISA. Serum samples from 31 of 33 patients had detectable SAP antigen, with concentrations ranging from 6.3 to 19.0 ng/ml. These results indicate that the inhibition ELISA with MAb CAP1 is effective in detection of circulating SAP antigen and that this assay may be useful for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of invasive candidiasis.

Invasive or disseminated candidiasis is a serious and often fatal complication that can occur frequently in immunocompromised patients. The development of invasive candidiasis may also be provoked by intravascular lines that are used for a long period, by indwelling catheters, or after major surgery and antibacterial treatment (1, 2, 9, 16, 28, 34). The diagnosis of invasive candidiasis is difficult because there are no specific clinical manifestations, and conventional microbiological methods usually lack both sensitivity and specificity (19, 34). The infection can be confirmed only by organ biopsy, by aspiration of a normally sterile body fluid, or at necropsy. Blood or urine cultures are often negative or become positive only after a long delay (7). Consequently, therapy is often initiated late in the course of infection, resulting in substantial morbidity and mortality (23). Therefore, it is important to diagnose tissue invasion at an early stage, as it can be successfully treated with amphotericin B.

Much effort has been made to develop reliable tests for rapid diagnosis of invasive candidiasis leading to appropriate therapy. These diagnostic techniques include detection of fungal nucleic acid by PCR (20), detection of (1-3)-β-d-glucan and d-arabinitol (32, 46), detection of circulatory Candida antigens (6, 10, 12, 14, 15, 27, 30, 35, 39, 43, 45), and detection of antibodies directed against different Candida antigens (5, 13, 37, 48). However, each of these techniques has limitations, and none of them has obtained wide acceptance for diagnosis of invasive candidiasis (36).

Secreted aspartyl proteinase (SAP) of Candida albicans is well known as a virulence factor which plays an important role during invasive hyphal growth of C. albicans. At the initial step of invasion, production of the enzyme is increased and it may participate in degrading the surface barrier prior to hyphal formation and deeper invasion into host tissues (3, 11, 22, 29, 33, 38, 41, 42, 47). It was found that candidiasis patients have high antibody titers against the enzyme, and the enzyme was detected in the sera of candidiasis patients (18, 24, 25, 43). The advantage of using a pathogenic factor such as SAP as a direct serodiagnostic marker of candidiasis lies in its potential to differentiate invasive disease from simple colonization. Therefore, detection of SAP in sera may be indicative of active candidiasis.

In a previous study, we produced and characterized a monoclonal antibody (MAb), CAP1, which was found to be highly specific against SAP1 (30). MAb CAP1 showed high sensitivity and was capable of detecting 2 and 16 ng of the antigen per ml by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and slot blot tests, respectively. It is therefore possible to use this monoclonal antibody as a diagnostic tool for detection of SAP antigen in sera of candidiasis patients.

In this study, three different ELISAs were compared in order to develop a new method for detection of circulating SAP antigen based on the use of MAb CAP1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

SAP antigen of C. albicans.

The SAP1 antigen was purified from the culture supernatant of C. albicans, as described previously (29). Analysis of purified SAP1 antigen by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis followed by staining with Coomassie blue and Western blotting with MAb CAP1 revealed only one spot.

MAb CAP1.

MAb CAP1 (immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1] type) was described previously (30). The antibody is highly specific for SAP1 and is able to detect 2 and 16 ng of the antigen per ml by ELISA and slot blot tests, respectively. The epitope of SAP1 recognized by the MAb was the proteinaceous part of SAP1, and the epitope of the MAb was located in the Asp77-to-Gly103 sequence. This MAb did not react with C. albicans whole-cell extract and mannoprotein extract in Western blot analysis.

Sera.

A total of 33 sera of candidiasis patients were kindly provided by the Korean Institute of Tuberculosis and the Korean National Institute of Health. The sera were obtained from patients with proven or highly suspected candidiasis caused by C. albicans on the basis of mycological and/or serological tests (isolation by culture, API 20C Aux system, and positive serological tests). Patients were classified as leukemia patients (n = 13), cancer patients (n = 8), pneumonia patients (n = 4), and pulmonary tuberculosis patients (n = 8), according to their clinical presentations. Sera from 12 patients with serologically confirmed aspergillosis were also included. Normal sera were obtained from 13 healthy volunteers with no history of candidiasis.

Standard ELISA.

Polystyrene 96-well plates were coated with 1 μg of purified SAP1 antigen diluted in carbonate buffer (pH 9.4) per well. The plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. After incubation, the plates were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) and were blocked by incubation with 200 μl of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBST per well for 2 h at 37°C. After three additional washes with PBST, 100-μl samples of 1:100 diluted patients’ sera were added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After being washed as described above, the plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h with 100 μl of peroxidase-conjugated anti-human IgG (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) diluted 1:3,000 in PBST. After incubation at 37°C for 2 h, the plates were washed three times with PBST and 100 μl of substrate solution was added. The substrate solution was prepared immediately before use by dissolving 0.4 mg of o-phenylenediamine (Sigma) per ml in 0.05 M citrate buffer (pH 5.2) and then adding hydrogen peroxide at a final concentration of 0.005%. The plates were incubated for 20 min in darkness. The reaction was terminated with 50 μl of 4 N H2SO4, and optical densities at 490 nm (OD490) were measured with an ELISA reader (Microplate Reader 450; Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.).

Antigen capture ELISA.

Polystyrene 96-well plates were coated with 100 μl of purified MAb CAP1 (10 μg/ml) diluted in carbonate buffer (pH 9.4) overnight at 4°C. Then, the plates were washed three times with PBST and blocked with 1% BSA in PBST by incubation at 37°C for 2 h. After three washes with PBST, 100-μl samples of patients’ sera pretreated with 2% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and neutralized with carbonate buffer, pH 9.6, were added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Plates were again washed three times with PBST, and 100 μl of mouse anti-SAP1 polyclonal antibody diluted at 1:1,000 in PBST was added. The mouse anti-SAP1 polyclonal antibody was prepared by immunizing mice with purified SAP1 as described previously (30). After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, the plates were washed three times with PBST, and 100 μl of peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Sigma) diluted at 1:3,000 in PBST was added. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, the plates were washed three times with PBST and substrate solution was added. Subsequent steps were identical to the standard ELISA described above.

Inhibition ELISA.

Purified SAP1 (10 μg/ml) diluted in carbonate buffer, pH 9.4, was added to each well of polystyrene 96-well plates and incubated overnight at 4°C. After being coated, the plates were washed three times with PBST and blocked with 1% BSA in PBST by incubation at 37°C for 2 h. After three washes with PBST, mixtures of patients’ sera and MAb CAP1 (10 μg/ml) were added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Mixtures of patients’ sera and MAb CAP1 were prepared by incubating patients’ sera in PBST with MAb CAP1 at 4°C overnight or at 37°C for 2 h. Plates were washed three times with PBST, and peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Sigma) diluted at 1:3,000 in PBST was added, followed by incubation at 37°C for 2 h. After three washes with PBST, substrate solution was added; subsequent steps were identical to the standard ELISA described above.

Statistical analysis.

Each assay was repeated three times for at least two independent assays, and the results are expressed as mean OD for each determination. Test results were considered positive if the OD exceeded the mean OD ± 3 standard deviations (SDs) obtained with the known negative control sera.

RESULTS

Standard ELISA.

In the standard antibody detection ELISA, a cutoff value was determined by calculating an average OD for 13 normal serum samples (0.124) plus 3 standard deviations (0.095). The cutoff OD was 0.219. As shown in Table 1, based on this cutoff value, 23 serum samples of the 33 candidiasis patients were positive, resulting in 69.7% true positivity. However, 6 of 12 serum samples (50.0%) obtained from patients with aspergillosis also were positive reactions (Table 1). These results indicated that the standard anti-SAP antibody detection ELISA is not useful for diagnostic purposes due to low sensitivity and cross-reactivity with other fungal infections.

TABLE 1.

Results of three different ELISAsa

| Serum | Underlying diseaseb | Standard ELISA resultc | Antigen capture

ELISA

|

Inhibition ELISA

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resultc | SAP concn (ng/ml)d | Resultc | SAP concn (ng/ml)e | |||

| 1 | AML | P | P | 14.0 | P | 15.0 |

| 2 | AML | N | P | 16.7 | P | 16.4 |

| 3 | CML | N | P | 15.7 | P | 15.5 |

| 4 | CML | N | P | 16.7 | P | 16.0 |

| 5 | CML | P | P | 14.6 | P | 15.0 |

| 6 | ALL | N | P | 11.2 | P | 11.7 |

| 7 | ALL | P | P | 10.8 | P | 10.4 |

| 8 | ALL | P | P | 12.7 | P | 12.6 |

| 9 | CLL | N | P | 11.6 | P | 11.4 |

| 10 | CLL | N | P | 8.7 | P | 7.7 |

| 11 | CLL | P | P | 12.6 | P | 13.5 |

| 12 | Lymphoma | P | P | 10.7 | P | 11.4 |

| 13 | Lymphoma | N | P | 18.1 | P | 18.5 |

| 14 | Stomach cancer | P | P | 19.2 | P | 19.0 |

| 15 | Stomach cancer | P | P | 6.6 | P | 6.6 |

| 16 | Duodenal cancer | P | N | NDf | N | ND |

| 17 | Liver cancer | P | P | 12.0 | P | 12.9 |

| 18 | Liver cancer | P | P | 6.3 | P | 6.3 |

| 19 | Liver cancer | P | P | 6.9 | P | 8.0 |

| 20 | Lung cancer | N | P | 12.3 | P | 12.5 |

| 21 | Lung cancer | P | P | 10.0 | P | 11.5 |

| 22 | Pneumonia | N | P | 17.4 | P | 16.9 |

| 23 | Pneumonia | P | P | 13.3 | P | 13.6 |

| 24 | Pneumonia | P | P | 9.7 | P | 10.9 |

| 25 | Pneumonia | P | P | 8.8 | P | 9.7 |

| 26 | Tuberculosis | P | N | ND | N | ND |

| 27 | Tuberculosis | P | P | 12.1 | P | 12.4 |

| 28 | Tuberculosis | P | P | 8.7 | P | 9.4 |

| 29 | Tuberculosis | P | P | 10.0 | P | 10.7 |

| 30 | Tuberculosis | N | P | 14.9 | P | 15.2 |

| 31 | Tuberculosis | P | P | 12.8 | P | 12.3 |

| 32 | Tuberculosis | P | P | 7.4 | P | 7.2 |

| 33 | Tuberculosis | P | P | 10.4 | P | 10.9 |

| 34 | Aspergillosis | P | P | 4.4 | N | ND |

| 35 | Aspergillosis | N | N | ND | N | ND |

| 36 | Aspergillosis | P | P | 4.6 | P | 4.6 |

| 37 | Aspergillosis | N | N | ND | N | ND |

| 38 | Aspergillosis | N | N | ND | N | ND |

| 39 | Aspergillosis | P | N | ND | N | ND |

| 40 | Aspergillosis | N | N | ND | N | ND |

| 41 | Aspergillosis | P | N | ND | N | ND |

| 42 | Aspergillosis | P | N | ND | N | ND |

| 43 | Aspergillosis | N | N | ND | N | ND |

| 44 | Aspergillosis | P | N | ND | N | ND |

| 45 | Aspergillosis | N | N | ND | N | ND |

| 46 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

| 47 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

| 48 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

| 49 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

| 50 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

| 51 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

| 52 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

| 53 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

| 54 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

| 55 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

| 56 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

| 57 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

| 58 | N | N | ND | N | ND | |

Sera used in this study were kindly provided by the Korean Institute of Tuberculosis and the Korean National Institute of Health. Serum samples are as follows: 1 to 33, sera from patients with candidiasis; 34 to 45, sera from patients with aspergillosis; 46 to 58, negative control sera from healthy volunteers. Each assay was repeated three times for at least two independent assays. Test results were considered positive if the OD exceeded the mean OD ± 3 SDs obtained with the negative control sera.

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

P, positive; N, negative.

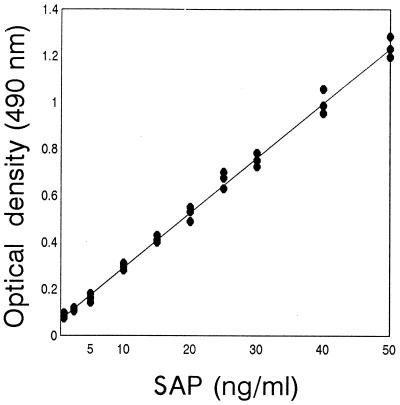

Determined by comparing the OD to the standard curve shown in Fig. 1.

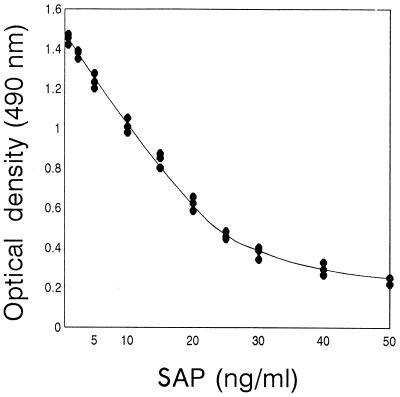

Determined by comparing the OD to the standard curve shown in Fig. 2.

ND, not determined.

Antigen capture ELISA.

Figure 1 shows the standard curve of the amount of SAP detected by the antigen capture ELISA. This system is able to detect up to 1 ng of SAP per ml in PBS. The results of the antigen capture ELISA using sera are shown in Table 1. The cutoff value, 0.157, was calculated from average OD for 13 normal sera (0.082) plus 3 standard deviations (0.075). Thirty-one of the 33 serum samples obtained from patients with candidiasis were determined to be positive, and 2 of the 12 aspergillosis patients’ sera (sera 34 and 36) were determined to be positive even though the OD were 0.175 and 0.182, respectively. Sera from all candidiasis patients had detectable circulating SAP antigen, ranging from 6.3 to 19.2 ng/ml, except for two sera (sera 16 and 26) which were determined to be negative. Twenty-three of 31 (74.2%) serum samples had detectable antigen, ranging from 10.0 to 19.2 ng/ml, and 8 of 31 (25.8%) serum samples had antigen levels of less than 10 ng/ml. The mean SAP antigen concentration detected in the sera of candidiasis patients was approximately 12 ng/ml.

FIG. 1.

Amount of SAP detected by antigen capture ELISA. Data are averages calculated from triplate OD obtained with three different batches of in vitro-produced SAP diluted in PBS. Standard deviations were artificially calculated from calibration curves with OD corresponding to different SAP concentrations.

Inhibition ELISA.

Figure 2 shows the standard curve of the amount of SAP detected by the inhibition ELISA. This system is able to detect as little as 1 ng of SAP per ml in PBS. The results of the inhibition ELISA using sera are shown in Table 1. The cutoff value, 1.324, was calculated from average OD for 13 normal sera (1.581) minus 3 standard deviations (0.257). Thirty-one of the 33 serum samples obtained from patients with candidiasis were determined to be positive, and 1 of the 12 aspergillosis patients’ sera (serum 36) was determined to be positive. Most sera from candidiasis patients had detectable circulating SAP antigen, ranging from 6.3 to 19.0 ng/ml, except for two sera (sera 16 and 26) which were determined to be negative. Twenty-four of 31 (77.4%) serum samples had detectable antigen, ranging from 10.0 to 19.2 ng/ml, and 7 of 31 (22.6%) serum samples had antigen levels of less than 10 ng/ml. The mean SAP antigen concentration detected in the sera of candidiasis patients was approximately 12.3 ng/ml.

FIG. 2.

Amount of SAP detected by inhibition ELISA. Data are averages calculated from triplate OD obtained with three different batches of in vitro-produced SAP diluted in PBS. Standard deviations were artificially calculated from calibration curves with OD corresponding to different SAP concentrations.

Comparison of the three ELISA procedures.

The results obtained from the three different ELISA procedures are summarized in Table 2. As expected, the standard ELISA showed a relatively low sensitivity, 69.7%, and a specificity of 76.0%. The positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and efficiency of this method were 79.3, 65.5, and 72.4%, respectively. For the antigen capture ELISA and the inhibition ELISA, the values for all categories which are meaningful for determining the usefulness of diagnostic procedures were improved significantly. The sensitivity was 93.9% for both procedures. However, the other categories, including specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and efficiency, were better for the inhibition ELISA than for the antigen capture ELISA. In the inhibition ELISA, the specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and efficiency were 96.0, 96.9, 92.3, and 94.8%, respectively. These results suggested that these methods for detecting circulatory SAP antigen in the sera of candidiasis patients are more reasonable in their specificity and sensitivity than are classical methods which detect antibodies produced by the patient against various antigens. In this study, the inhibition ELISA using purified SAP and MAb CAP1 showed the highest sensitivity and specificity. Therefore, the inhibition ELISA method developed here might be useful for diagnosis of candidiasis.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of three different ELISAs

| Parametera | Result for ELISA

method (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | Antigen capture | Inhibition | |

| Sensitivity | 69.7 | 93.9 | 93.9 |

| Specificity | 76.0 | 92.0 | 96.0 |

| Positive predictive value | 79.3 | 93.9 | 96.9 |

| Negative predictive value | 65.5 | 92.0 | 92.3 |

| Efficiency | 72.4 | 93.1 | 94.8 |

Sensitivity = TP/(TP + FN); specificity = TN/(FP + TN); positive predictive value = TP/(TP + FP); negative predictive value = TN/(TN + FN); efficiency = (TP + TN)/(TP + FP + TN + FN) (where TP is true positive, FP is false positive, TN is true negative, and FN is false negative).

DISCUSSION

There is increasing interest in the use of reliable serological tests for rapid diagnosis and prophylactic treatment of invasive candidiasis in immunocompromised patients. Serological detection of antibodies to Candida antigens in patients with invasive candidiasis can fail because patients cannot produce an adequate immune response, especially immune-deficient patients, or because the first serum sample is taken before antibodies have been formed (4). Moreover, high titers of antibody may be the results of simple colonization of Candida spp. or a related fungal infection (8). In fact, antibody titers against Candida antigens are not useful in diagnosis of candidiasis, probably because a fairly high frequency of healthy people also have antibodies against Candida antigens, as Candida spp. are commensals in the human mouth, vaginal mucosa, and gastrointestinal tract. In addition, serological tests for antibodies are of limited diagnostic value because antibody titers may remain elevated for long periods of time during and after therapy. Therefore, detection of Candida circulating antigens in body fluids or sera could be more reliable for diagnosis of active invasive candidiasis and to facilitate the early diagnosis of the mycosis and confirm a preliminary diagnosis when antibody detection is nonconclusive.

Several attempts have been made to detect circulating antigens of the fungus by various biochemical and immunological techniques (6, 12, 14, 19, 21, 26, 27, 31, 35, 39, 44, 48). Some of these diagnostic assays are commercially available, but their clinical usefulness remains controversial due to their low sensitivity and specificity.

In this study, we developed a method for diagnosis of candidiasis by means of the detection of circulating SAP antigen. The novelty of the method developed in the present study was the use of a MAb (MAb CAP1) directed against SAP.

As expected, a standard ELISA based on detection of antibody against SAP revealed a relatively low sensitivity, 69.7%, and a specificity of 76.0%. Six of 12 serum samples obtained from aspergillosis patients showed false-positive reactions. It is known that Aspergillus spp. also secrete aspartic proteinase (17, 40). Therefore, this result was due to cross-reactivity of antibodies against aspartic proteinase of Aspergillus spp. with SAP. This suggests that antibody detection is not reliable, since a great number of pathogenic fungi also produce aspartic proteinase. In an antigen capture ELISA and an inhibition ELISA using MAb CAP1, the values for categories that are meaningful for evaluating the usefulness of diagnostic procedures were improved significantly. For both of the procedures, 31 of 33 serum samples obtained from candidiasis patients were determined to be positive, and the specificity was 93.9%. Two serum samples (sera 16 and 26) which were positive by the standard ELISA were negative by the antigen capture ELISA and the inhibition ELISA. This suggests that a detectable amount of SAP antigen was not contained in those sera even though antibodies against the antigen were detectable. Although not clear, these data suggest the possibility that the two serum samples were not derived from patients with true active or progressive candidiasis. The two ELISA procedures can evaluate true active candidiasis that may be difficult for the antibody detection standard ELISA. Furthermore, 10 serum samples (sera 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 10, 13, 20, 22, and 30) were determined to be negative by the standard ELISA but positive by the antigen capture ELISA and the inhibition ELISA. This suggested that antibodies were not produced despite a significant amount of SAP present in the sera, which may be explained by the possibility that the patients were immunocompromised and that sufficient amounts of antibodies were not produced. This also suggested another possibility: that the two ELISA procedures could be useful for early diagnosis, especially for immunocompromised patients and those with the juvenile form of mycosis. However, false-positive results due to minor cross-reactions with another mycosis, aspergillosis, were also observed for both of the procedures. Two serum samples were positive with the antigen capture ELISA, and one serum sample was positive with the inhibition ELISA. However, the mean antigen concentrations observed in these heterologous sera were much lower than that recorded in the sera of candidiasis patients.

All of the sera of candidiasis patients had detectable amounts of circulating SAP antigen except for two samples (sera 16 and 26). The predicted SAP concentrations in positive sera for the antigen capture ELISA and the inhibition ELISA were similar. This supports the concept that these two ELISA methods are more reliable than antibody detection ELISA. Although the sensitivity of both procedures was 93.9%, the other categories, including specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and efficiency, were better for the inhibition ELISA than for the antigen capture ELISA. In the inhibition ELISA, the specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and efficiency were 96.0, 96.9, 92.3, and 94.8%, respectively. These results suggest that the inhibition ELISA method for detection of circulatory SAP antigen in the sera of candidiasis patients is more reasonable in specificity and sensitivity than the standard ELISA method for detecting antibodies against antigen and the antigen capture ELISA. However, the MAb used in this study did not react with aspartyl proteinases of C. parapsilosis and C. tropicalis, other emerging pathogens of candidiasis; thus, it is reasonable to assume that candidiasis caused by the above fungi could not be detected by this technique.

In conclusion, detection of SAP antigen in sera by an inhibition ELISA using MAb CAP1 appears to be of value for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of candidiasis patients. Detection of SAP in the sera of patients allowed early recognition of Candida infection, especially in patients with tissue-proven invasive candidiasis, for which the serological diagnosis was obtained several days before the microbiological diagnosis was made. However, a larger prospective study with a larger number of specimens and different concentrations of samples are needed to generalize this method for clinical use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from Chung-Ang University (1999).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bodey G P, Fainstein V. Candidiasis. In: Bodey G P, Fainstein V, editors. Candidiasis. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1985. pp. 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodey G P, Anaissie E J. Chronic systemic candidiasis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:855–857. doi: 10.1007/BF01963770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borg M, Rüchel R. Expression of extracellular acid proteinase by proteolytic Candida spp. during experimental infection of oral mucosa. Infect Immun. 1988;56:626–631. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.3.626-631.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckley H R, Richardson M D, Evans E G V, Wheat L J. Immunodiagnosis of invasive fungal infection. J Med Vet Mycol. 1992;30(Suppl. 1):249–260. doi: 10.1080/02681219280000941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakrabarti A, Roy P, Kumar D, Sharma B K, Chugh K S, Panigrahi D. Evaluation of three serological tests for detection of anti-candidal antibodies in diagnosis of invasive candidiasis. Mycopathologia. 1994;126:3–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01371166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Bernardis F, Girmenia C, Boccanera M, Adriani D, Martino P, Cassone A. Use of a monoclonal antibody in a dot immunobinding assay for detection of a circulating mannoprotein of Candida spp. in neutropenic patients with invasive candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3142–3146. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3142-3146.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Repentigny L, Reiss E. Current trends in immunodiagnosis of candidiasis and aspergillosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6:301–312. doi: 10.1093/clinids/6.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Repentigny L, Kaufman L, Cole G T, Kruse D, Latge J P, Matthews R C. Immunodiagnosis of invasive fungal infections. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32(Suppl. 1):239–252. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards J E, Lehrer R I, Fieher T J, Young L S. Severe candidal infections: clinical perspective, immune defense mechanisms, and current concepts of therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89:91–106. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-1-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escuro R S, Jacobs M, Gerson S L, Machicao A R, Lazarus H M. Prospective evaluation of a Candida antigen detection test for invasive candidiasis in immunocompromised adult patients with cancer. Am J Med. 1989;87:621–627. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(89)80393-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fallon K, Bausch K, Noonan J, Huguenel E, Tamburini P. Role of an aspartic proteinase in disseminated Candida albicans infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:551–556. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.551-556.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferreira R P, Yu B, Niki Y, Armstrong D. Detection of Candida antigenemia in disseminated candidiasis by immunoblotting. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1075–1078. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.5.1075-1078.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Ruiz J C, Arilla M D C, Regulez P, Quindos G, Alvarez A, Ponton J. Detection of antibodies to Candida albicans germ tubes for diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring of invasive candidiasis in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3284–3287. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3284-3287.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gómez B L, Figueroa J I, Hamilton A J, Ortiz B, Robledo M A, Hay R J, Restrepo A. Use of monoclonal antibodies in diagnosis of paracoccidioidomycosis: new strategies for detection of circulating antigens. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3278–3283. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3278-3283.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrent P, Stynen D, Hernando F, Fruit J, Poulain D. Retrospective evaluation of two latex agglutination tests for detection of circulating antigen during invasive candidosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2158–2164. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.2158-2164.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horn R, Wong B, Kieln T E, Armstrong D. Fungemia in a cancer hospital: changing frequency, earlier onset and results of therapy. Rev Infect Dis. 1985;7:646–655. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.5.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue H, Kimura T, Makabe O, Takahashi K. The gene and deduced protein sequences of the zymogen of Aspergillus niger acid proteinase A. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19484–19489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishiguro A, Homma M, Sukai T, Higashide K, Torh S, Tanaka K. Detection of antigen components of Candida albicans by reaction with antibody from candidal vaginitis patients and healthy females. J Med Vet Mycol. 1992;30:281–292. doi: 10.1080/02681219280000371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones J M. Laboratory diagnosis of invasive candidiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:32–45. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jordan J A. PCR identification of four medically important Candida species by using a single primer pair. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2962–2967. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2962-2967.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahn F W, Jones J M. Latex agglutination tests for detection of Candida antigens in sera of patients with invasive candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:579–587. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon-Chung K J, Lehman D, Good C, Magee P T. Genetic evidence for role of extracellular proteinase in virulence of Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1985;49:571–575. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.3.571-575.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lew M A. Diagnosis of systemic Candida infections. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1989;40:87–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.40.020189.000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacDonald F, Odds F C. Inducible proteinases of Candida albicans in diagnostic serology and the pathogenesis of systemic candidiasis. J Med Microbiol. 1980;13:423–435. doi: 10.1099/00222615-13-3-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacDonald F, Odds F C. Purified Candida albicans proteinase in the serological diagnosis of systemic candidosis. JAMA. 1980;243:2409–2411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthews R C, Burnie J P. Diagnosis of systemic candidiasis by an enzyme-linked dot immunobinding assay for a circulating immunodominant 47-kilodalton antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:459–463. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.3.459-463.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthews R C. Early diagnosis of systemic candidal infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31:809–812. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meunier-Carpentier F, Kiehn T E, Armstrong D. Fungemia in the immunocompromised host. Am J Med. 1981;71:363–370. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Na B K, Lee S I, Kim S O, Park Y K, Bai G H, Kim S J, Song C Y. Purification and characterization of extracellular aspartic proteinase of Candida albicans. J Microbiol. 1997;35:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Na B K, Chung G T, Song C Y. Production, characterization and epitope mapping of a monoclonal antibody against aspartic proteinase of Candida albicans. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:429–433. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.3.429-433.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura A, Ishikawa N, Suzuki H. Diagnosis of invasive candidiasis by detection of mannan antigen by using the avidin-biotin enzyme immunoassay. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2363–2367. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2363-2367.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obayashi T, Yoshida M, Mori T, Goto H, Yasuoka A, Iwasaki H, Teshima H, Kohno S, Horiuchi A, Ito A, Yamaguchi H, Shimada K, Kawai T. Plasma (1-3)-β-d-glucan measurement in diagnosis of invasive deep mycosis and fungal febrile episodes. Lancet. 1995;345:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Odds F C. Candida albicans aspartic proteinase as a virulence factor in the pathogenesis of Candida albicans. Zentbl Bakteriol Hyg. 1985;260:539–542. doi: 10.1016/s0176-6724(85)80069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Odds F C, editor. Candida and candidosis. London, United Kingdom: Tindall; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Platenkamp G J, Vanduin A M, Porsius J C, Schouten H J A, Zondervan P E, Michel M F. Diagnosis of invasive candidiasis in patients with and without signs of immune deficiency: a comparison of six detection methods in human serum. J Clin Pathol. 1987;40:1162–1167. doi: 10.1136/jcp.40.10.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ponton J. Avances en el diagnostico de laboratorio de la candidiasis sistemica. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1996;13(Suppl. 1):16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quindos G, Ponton J, Cisterna R, Mackenzi D W R. Value of detection of antibodies of Candida albicans germ tube in the diagnosis of systemic candidiosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:178–183. doi: 10.1007/BF01963834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ray T L, Payne C D, Morrow B J. Candida albicans acid proteinase: characterization and role in candidiasis. Adv Exp Med Sci. 1991;306:173–183. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-6012-4_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reboli A C. Diagnosis of invasive candidiasis by a dot immunobinding assay for Candida antigen detection. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;24:796–802. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.3.518-523.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reichard U, Eiffert H, Rüchel R. Purification and characterization of an extracellular aspartic proteinase from Aspergillus fumigatus. J Med Mycol. 1995;32:427–436. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross I K, De Bernardis F, Emerson G W, Cassone A, Sullivan P A. The secreted aspartic proteinase of Candida albicans: physiology of secretion and virulence of a proteinase-deficient mutant. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:687–694. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-4-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rüchel R. Properties of purified proteinase from the yeast Candida albicans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;695:99–113. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(81)90274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rüchel R, Boning-Stutzer B, Mari A. A synoptical approach to the diagnosis of candidiosis, relying on serological antigen and antibody tests, on culture and evaluation of clinical data. Mycoses. 1988;31:87–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stynen D, Goris A, Sarfati J, Latge J P. A new sensitive sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect galactofuran in patients with invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:497–500. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.497-500.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walsh T J, Hathorn J W, Sobel J D, Merz W G, Sanchez V, Maret S M, Buckley H R, Pfaller M A, Schaufele R, Silva C, Navarro E, Lecciones J, Chandrasekar P, Lee J, Pizzo P A. Detection of circulating Candida enolase by immunoassay in patients with cancer and invasive candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1026–1031. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104113241504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walsh T J, Merz W G, Lee J W, Schaufele R, Scin T, Whitcome P O, Ruddel M, Burns W, Wingard J R, Switchenko A C, Goodman T, Pizzo P A. Diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring of invasive candidiasis by rapid enzyme detection of serum d-arabinitol. Am J Med. 1995;99:164–172. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wingard J, Dick J, Merz W, Sandford G, Saral R, Burns W. Differences in virulence of clinical isolates of Candida tropicalis and Candida albicans in mice. Infect Immun. 1982;37:833–836. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.2.833-836.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zoller L, Kramer I, Kappe R, Sonntag H G. Enzyme immunoassays for invasive Candida infections: reactivity of somatic antigens of Candida albicans. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:860–867. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.9.1860-1867.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]