Key Points

Question

What percentage do prescription drugs contribute to total fee-for-service Medicare spending and how has this changed from 2008 to 2019?

Findings

In this descriptive, serial, cross-sectional analysis of a 20% random sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, the estimated proportion of total annual spending attributed to prescription drugs was 24.0% in 2008 and 27.2% in 2019, net of estimated rebates and discounts.

Meaning

The findings provide an estimate of the spending on prescription drugs among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries from 2008 to 2019.

Abstract

Importance

Prescription drug spending is a topic of increased interest to the public and policymakers. However, prior assessments have been limited by focusing on retail spending (Part D–covered drugs), omitting clinician-administered (Part B–covered) drug spending, or focusing on all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, regardless of their enrollment into prescription drug coverage.

Objective

To estimate the proportion of health care spending contributed by prescription drugs and to assess spending for retail and clinician-administered prescriptions.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Descriptive, serial, cross-sectional analysis of a 20% random sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in the United States from 2008 to 2019 who were continuously enrolled in Parts A (hospital), B (medical), and D (prescription drug) benefits, and not in Medicare Advantage.

Exposure

Calendar year.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Net spending on retail (Part D–covered) and clinician-administered (Part B–covered) prescription drugs; prescription drug spending (spending on Part B–covered and Part D–covered drugs) as a percentage of total per-capita health care spending. Measures were adjusted for inflation and for postsale rebates (for Part D–covered drugs).

Results

There were 3 201 284 beneficiaries enrolled in Parts A, B, and D in 2008 and 4 502 718 in 2019. In 2019, beneficiaries had a mean (SD) age of 71.7 (12.0) years, documented sex was female for 57.7%, and 69.5% had no low-income subsidies. Total per-capita spending was $16 345 in 2008 and $20 117 in 2019. Comparing 2008 with 2019, per-capita Part A spending was $7106 (95% CI, $7084-$7128) vs $7120 (95% CI, $7098-$7141), Part B drug spending was $720 (95% CI, $713-$728) vs $1641 (95% CI, $1629-$1653), Part B nondrug spending was $5113 (95% CI, $5105-$5122) vs $6702 (95% CI, $6692-$6712), and Part D net spending was $3122 (95% CI, $3117-$3127) vs $3477 (95% CI, $3466-$3489). The proportion of total annual spending attributed to prescription drugs increased from 24.0% in 2008 to 27.2% in 2019, net of estimated rebates and discounts.

Conclusions and Relevance

In 2019, spending on prescription drugs represented approximately 27% of total spending among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part D, even after accounting for postsale rebates.

This cross-sectional analysis estimates the proportion of health care spending contributed by prescription drugs as well as examines spending for retail and clinician-administered prescriptions.

Introduction

Prescription drug spending is a topic of substantial interest to policymakers and the public. The rapid increase in prescription drug prices1,2,3 and the recognition that high drug prices have limited patient access to medicines4,5,6 have increased the sense of urgency surrounding the need to address drug spending through policy intervention. Pharmaceutical industry advocates have long emphasized that prescription drugs represent only a small percentage—approximately 10%—of all health care spending, pointing to national health statistics of retail drug spending.7,8 However, this figure likely underestimates drug spending among Medicare beneficiaries.9 Given the role of Medicare as the primary payer for prescription drugs, it would be instructive to understand trends in prescription drug spending in the fee-for-service Medicare program and the share of spending consumed by prescription drugs.

Prior estimates of Medicare program spending on prescription drugs have shown increases in overall and per-capita spending over time but vary widely due to differences in the population represented and definitions of “drug” spending.7,8,10,11,12 Even within reports targeting fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, most estimated spending among those enrolled in Medicare Part A (hospital insurance) and Part B (medical insurance) and did not require beneficiaries to be enrolled in Part D (prescription drug insurance). For such studies, the share of fee-for-service Medicare spending contributed by drugs ranged from 15% to 23%.11,12

While virtually all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in Parts A and B, fewer (76% in 202113) are enrolled in Part D. Although some beneficiaries who are not enrolled in Part D may have little to no retail drug spending, many may purchase drugs either by paying cash or using another source of credible coverage (eg, retiree benefits, employer-sponsored plans, veterans’ benefits). As a result, studies seeking to define how prescription drugs contribute to overall health care spending among Medicare beneficiaries might have underestimated prescription drug spending when not restricting to those enrolled in Part D.

Methods

Data Source

This study was considered not human subjects research by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was not required. We used claims for a 20% random sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries. Our unit of observation was the person-year. We required individuals to be continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B, and D and not enrolled in Medicare Advantage within a calendar year, allowing individuals to enter the program in any month when they become eligible (typically when turning 65 years of age) and exit due to death. We defined Part A spending as any spending billed under the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (inpatient hospital care only), Skilled Nursing Facility, Home Health, or Hospice files. We defined Part B spending as any spending billed under the Outpatient, Carrier, or Durable Medical Equipment files. We defined Part D spending as any spending billed under the Part D Event files. Spending included amounts allowed by Medicare, coordination-of-benefits payments from other insurance carriers, and patient out-of-pocket liabilities.

Outcomes

Our key study outcomes were annual net spending on retail (Part D–covered) and clinician-administered (Part B–covered) prescription drugs and total prescription drug spending (spending on Part B–covered and Part D covered–drugs combined) as a percentage of total per-capita health care spending. Secondary outcomes included per-capita spending on hospital (Part A), nondrug medical (Part B), and total spending (all services combined).

Statistical Analysis

Prescription drug spending in Medicare Part B is based on average sales prices, and observed spending is net of rebates and other price concessions. Part B spending includes a markup of 6% (or 4.3% since 2013 due to sequestration) for most drugs over our study period. We disaggregated total medical spending on Part B by prescription drug spending and nondrug spending using Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Average Sales Price files and the Outpatient Prospective Payment System Addendum B files from 2008 to 2019.14,15 We included spending for the drugs alone, excluding administration fees. Because we were unable to accurately account for spending on drugs administered for in-hospital care (inpatient administration), in postacute skilled nursing facilities, or as part of a prospective payment (eg, medications given with hemodialysis), we considered such spending as nondrug spending.

For Part D spending, observed spending in the claims data is gross spending and does not include postsale rebates. To account for rebates, we adjusted gross spending by mean annual rebate amounts reported by the Medicare boards of trustees in the annual report to Congress, which ranged from 10.4% in 2008 to 26.7% in 2019.16

We adjusted all dollars to 2019 US dollars using the personal consumption expenditures–health index.17 Beneficiaries without spending on a specific service subcomponent were included as having $0 in spending. Otherwise, there were no missing values in the data. Per-capita spending estimates are presented with 95% CIs. Analyses were descriptive and statistical testing was not performed. Data management and analysis were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Sensitivity Analysis

The primary analysis included only beneficiaries enrolled in all parts of the fee-for-service Medicare benefit (A, B, and D, and no Medicare Advantage). Other estimates of Medicare spending were typically restricted to beneficiaries enrolled in Parts A and B and did not require Part D enrollment or they focused only on federal program spending. To compare with other published reports, in sensitivity analyses we removed restrictions to Part D enrollment and replicated all analyses.

Results

The number of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in the 20% random sample enrolled in Parts A, B, and D and not enrolled in Medicare Advantage who were included in the analysis was 3 201 284 in 2008 and 4 502 718 in 2019. This reflects both a growing number of Medicare beneficiaries and of Part D enrollees (Part D enrollment increased from 57.5% of eligible Part A and B enrollees to 75.0% between 2008 and 2019) and a shift from fee-for-service Medicare to Medicare Advantage over the same period (eTable 1 in the Supplement). In 2019, beneficiaries had a mean (SD) age of 71.7 (12.0) years, and documented sex was female for 57.7%. Characteristics of the study population were relatively stable over time, although the percentage without a low-income subsidy (eg, those who are not eligible for partial or full low-income subsidies to lower their spending on health care services) increased from 53.8% to 69.5% and the percentage eligible due to disability decreased from 30.0% to 23.4% between 2008 and 2019 (Table). These dynamics likely reflect the automatic enrollment of subsidy-eligible individuals into Part D and a shift over time from employer-based retiree benefits18 to Medicare Part D for non–subsidy-eligible populations.

Table. Baseline Characteristics for Continuously Enrolled Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries in Parts A, B, and D and No Medicare Advantage From 2008-2019a.

| Demographic | Beneficiaries, % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-2009 | 2010-2011 | 2012-2013 | 2014-2015 | 2016-2017 | 2018-2019 | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 70.5 (14.3) | 70.4 (14.2) | 70.6 (13.7) | 71.1 (13.1) | 71.4 (12.5) | 71.7 (12.0) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 61.5 | 60.6 | 59.5 | 58.7 | 58.1 | 57.7 |

| Male | 38.5 | 39.4 | 40.5 | 41.3 | 41.9 | 42.3 |

| Subsidy status | ||||||

| Full | 37.6 | 37.2 | 33.4 | 28.8 | 26.8 | 24.9 |

| Partial | 5.4 | 5.2 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 2.7 |

| None | 53.8 | 54.6 | 59.5 | 64.6 | 67.1 | 69.5 |

| Missing | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.9 |

| Original reason for entitlement | ||||||

| Age | 69.0 | 68.6 | 70.1 | 72.3 | 74.0 | 75.8 |

| Disability | 30.0 | 30.4 | 29.0 | 26.8 | 25.2 | 23.4 |

| End-stage kidney disease | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Enrollment dynamics | ||||||

| Decedents | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 3.9 |

| New enrollees | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Medical comorbidity | ||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Alzheimer disease and dementia | 13.2 | 13.0 | 12.4 | 11.6 | 11.8 | 11.7 |

| Anemia | 26.6 | 27.3 | 26.7 | 25.1 | 24.3 | 24.3 |

| Asthma | 5.6 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 5.8 |

| Atrial fibrillation and flutter | 7.8 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 9.0 | 9.1 | 9.2 |

| Benign prostatic hyperplasiab | 5.0 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 8.3 |

| Cancer | ||||||

| Breastb | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.7 |

| Colorectal | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Lung | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Prostateb | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.4 |

| Cataract | 20.8 | 19.8 | 19.5 | 19.3 | 19.2 | 19.2 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 14.4 | 16.5 | 17.9 | 19.5 | 25.3 | 26.9 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 13.6 | 13.8 | 13.5 | 13.1 | 13.1 | 12.7 |

| Depression and mood disorders | 17.4 | 18.9 | 19.7 | 20.0 | 20.5 | 21.4 |

| Diabetes | 30.0 | 31.1 | 31.2 | 30.6 | 30.2 | 29.5 |

| Glaucoma | 10.4 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 9.1 | 10.3 |

| Hip and pelvic fracture | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 45.2 | 48.4 | 50.2 | 50.7 | 51.0 | 53.2 |

| Hypothyroidism | 13.8 | 15.0 | 16.0 | 16.8 | 17.2 | 17.7 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 33.2 | 32.7 | 31.4 | 29.9 | 29.3 | 29.1 |

| Osteoporosis | 7.9 | 8.0 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.7 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis | 30.9 | 32.5 | 33.5 | 34.2 | 36.3 | 37.4 |

| Stroke and transient ischemic attack | 4.9 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 |

Data from a 20% random sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries. Beneficiaries who are continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B, and D with no Medicare Advantage are included, allowing for beneficiaries to age into the program or to exit due to death. Comorbidities were measured using the chronic condition warehouse indicator for presence of comorbidity at the end of the specified year among the full sample.

Mean prevalence is lower than in other published reports because this comorbidity is typically captured among 1 sex only.

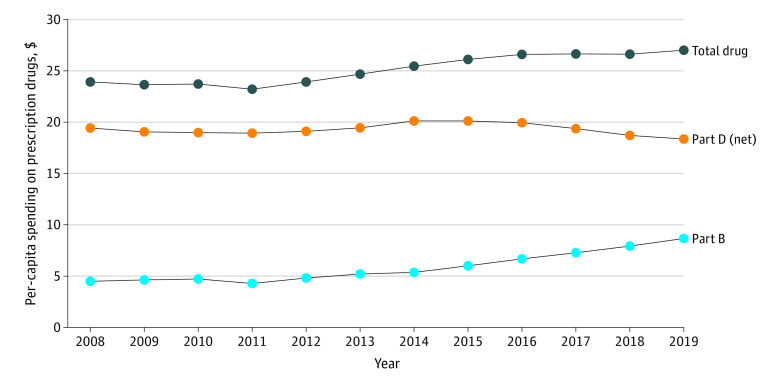

When considering overall spending trends in this study population, total per-capita spending was $16 062 (95% CI, $16 019-$16 105) in 2008 and $18 940 (95% CI, $18 885-$18 995) in 2019 (Figure 1; eTable 2 in the Supplement). Per-capita Part A spending was $7106 (95% CI, $7084-$7128) in 2008 and $7120 (95% CI, $7098-$7141) in 2019, Part B drug spending was $720 (95% CI, $713-$728) in 2008 and $1641 (95% CI, $1629-$1653) in 2019, Part B nondrug spending was $5113 (95% CI, $5105-$5122) in 2008 and $6702 (95% CI, $6692-$6712) in 2019, and Part D net spending was $3122 (95% CI, $3117-$3127) in 2008 and $3477 (95% CI, $3466-$3489) in 2019.

Figure 1. Per-Capita Spending by Service Category in Fee-for-Service Medicare, 2008-2019.

Data are from a 20% random sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries. Estimates are among individuals who are continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Parts A, B, and D and not in Medicare Advantage during a specified calendar year. Beneficiaries who age in or who die are included in these estimates. Prescription drug spending includes self-administered (Part D–covered) and physician-administered (Part B–covered) drugs. Spending does not include administration fees, hospital-administered drugs, or drugs that are not separately payable. Net spending reduces Part D gross spending by mean rebates as reported by year in the 2021 board of trustees report.16 Spending amounts include all sources of payment.

The proportion of total annual spending attributed to inpatient (Part A) spending was 44.2% in 2008 and 37.6% in 2019 (Figure 2). Part B (medical) nondrug spending represented 31.8% of total spending in 2008 and 34.5% in 2019. Part B drug spending represented 4.5% of total spending in 2008 and 8.7% in 2019. Part D net spending represented 19.4% of total spending in 2008 and 18.4% in 2019. Taken together, spending on prescription drugs (including both Part B– and Part D–covered drugs) increased from 24.0% of total per-capita spending in 2008 to 27.2% in 2019, net of estimated rebates and discounts (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Share of Per-Capita Spending by Service Category in Fee-for-Service Medicare, 2008-2019.

Data are from a 20% random sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries. Estimates are among individuals who are continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Parts A, B, and D and not in Medicare Advantage during a specified calendar year. Beneficiaries who age in or who die are included in these estimates. Prescription drug spending includes self-administered (Part D–covered) and physician-administered (Part B–covered) drugs. Spending does not include administration fees, hospital-administered drugs, or drugs that are not separately payable. Net spending reduces Part D gross spending by mean rebates as reported by year in the 2021 board of trustees report.16 Spending amounts include all sources of payment.

Figure 3. Trends in Per-Capita Prescription Drug Spending as a Percentage of Total Spending Under Fee-for-Service Medicare, 2008-2019.

Data are from a 20% random sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries. Estimates are among individuals who are continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Parts A, B, and D and not in Medicare Advantage during a specified calendar year. Beneficiaries who age in or who die are included in these estimates. Prescription drug spending does not include administration fees, hospital-administered drugs, or drugs that are not separately payable. Net spending reduces Part D gross spending by average rebates as reported by year in the 2021 board of trustees report.16

Sensitivity Analysis

In analyses focused on Part A and B enrollees without Medicare Advantage (regardless of Part D enrollment), there was somewhat lower per-capita spending on Part D– and Part B–covered medications than in the primary analysis (eTable 3 in the Supplement). For example, Part D per-capita spending when not restricted to Part D enrollees was $2394 in 2019 vs $3477 in our study population. Part B drug spending was $1464 when not restricted to Part D enrollees and $1641 in this study population.

Discussion

In 2019, spending on prescription drugs represented approximately 27% of total spending among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part D, even after accounting for postsale rebates, which have increased as a proportion of spending over time (from 10.4% in 2008 to 26.7% in 2019).

Prior estimates of the percentage of drug spending in fee-for-service Medicare ranged from 15% to 23%,11,12 although none have previously focused on beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B, and D. This may have led to an underestimate of drug spending in prior work because individuals without Part D might have used prescription drugs outside of their insurance coverage or through another credible source of coverage such as a retiree benefit. At the same time, the estimates reported in this study likely also underestimate total spending on drugs because they do not include spending on drugs dispensed in inpatient settings (including very high-cost chimeric antigen T-cell therapy medications introduced in later study years) or drugs reimbursed through prospective payment arrangements. The observed 128% increase in per-capita spending on clinician-administered drugs covered under Medicare Part B between 2008 and 2019 is similar to recent reports.11,19,20 Prior reports have suggested that this growth is due to price increases rather than greater use of drugs.10,11,20 Under the current fee-for-service program, Medicare does not have the ability to implement a formulary, even for the subset of products with treatment alternatives. Recent work suggests this lack of a formulary results in higher use of high-cost drugs in fee-for-service Medicare than in Medicare Advantage plans.20,21

It is possible that increased spending on prescription drugs may offset spending on other high-cost services needed by Medicare beneficiaries and may improve their health overall.22,23 Determining the source of spending increases will be important because higher spending could reflect greater access to innovative new drugs or drugs for conditions for which prior treatments were unavailable. Or it could represent price increases for existing products or high prices for less innovative drugs that lack competition. To place observed spending in context, between 2008 and 2019, there was a substantial replacement of brand-name drug use with generic drug use for many prevalent and chronic conditions. Instead of resulting in savings over the study period, per-capita spending increased. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission recently noted that the ability to achieve savings with generic substitution among nonsubsidized beneficiaries has likely plateaued due to the high use of generic drugs relative to brand-name drugs among most Medicare beneficiaries.13

Despite the increase in prescription drug spending overall and as a portion of total spending among Medicare beneficiaries, it is possible that high out-of-pocket costs are deterring some necessary care. For example, prior studies have found that many Medicare beneficiaries forego filling prescriptions for high-priced specialty drugs, even extremely effective drugs.4,24,25 Adherence also declines as individuals move from the initial benefit phase of Part D into the coverage gap where drugs shift from flat-fee co-payments to a co-insurance.26,27 It is possible that drugs would make up an even higher proportion of Medicare spending if they were used as intended by prescribers, both by increasing medication adherence and potentially reducing downstream nondrug spending that results from noninitiation or nonadherence.

There has been substantial policy interest in reducing prescription drug spending and in improving access to prescription drugs for Medicare beneficiaries. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 was recently passed by Congress and signed into law by President Joe Biden on August 16, 2022.28 This law includes elements of drug price negotiation for a subset of older high-priced drugs that lack competition in Medicare Part B or Part D (beginning in 2026), limits on drug price increases to the rate of inflation (beginning in 2023), and caps on out-of-pocket spending for Medicare Part D beneficiaries (beginning in 2024 and fully implemented in 2025). Although these changes could reduce spending, the lack of any limit on prices set for new drugs and the potential for increased medication use by beneficiaries who had previously been unable to afford to fill prescribed drugs make savings for the Medicare program less certain. It will be important to monitor how these future program changes affect beneficiary access to and Medicare spending on prescription drugs.

Even with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act,28 there remain several important gaps in affordability and access to prescription drugs for Medicare beneficiaries. For example, out-of-pocket spending for Part B–covered drugs for Medicare beneficiaries who lack supplemental coverage is substantial. The approximately 15% of fee-for-service beneficiaries who lack a Part B supplement must pay 20% of the Medicare-allowed amount, with no out-of-pocket limit. Although beneficiaries have the option to purchase a supplement during the first 6 months of eligibility for Medicare enrollment, many find the required premiums to be too costly and those who wish to enroll later may not be able to do so due to preexisting condition limits.

Next, when considering the offsetting effect of drug spending on downstream service use, it is important to note that in traditional Medicare, sponsors of stand-alone Part D plans lack strong financial incentives to manage medical spending. This may result in benefit designs or coverage decisions that lead to suboptimal medication access and adherence from the perspective of the Medicare program as a whole.

In addition, it is important to consider the effect of drug prices and spending on the affordability of Medicare premiums. Recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services increased Medicare premiums for all enrollees, citing potential budget constraints due in part to the approval of a high-cost drug for early-stage Alzheimer disease. The introduction of high-priced drugs that lack competition could ultimately limit beneficiaries’ ability to afford basic and/or supplemental coverage that allow them to obtain medications they may need.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this study focused strictly on fee-for-service Medicare enrollees who have Parts A, B, and D coverage from 2008 to 2019. Uptake of Part D has increased over time and in 2021 approximately three-quarters of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in the prescription drug benefit.13 An increasing proportion of Medicare beneficiaries are now enrolled in Medicare Advantage, nearly half of beneficiaries in 2022. Because Medicare Advantage has more utilization management tools, particularly under the medical benefit, it is possible that drugs make up a lower proportion of spending for individuals receiving care through those plans.20,21 As a result, the characteristics of beneficiaries in the fee-for-service Medicare program have changed over time, which could contribute to the observed spending patterns and shifts in spending by service component over time. However, the primary goal of this study was not to estimate what spending would be for a homogenous population but to summarize spending over time among those who are enrolled in the benefit (allowing this population to change to reflect current enrollment).

Second, the study findings may underestimate the contribution of prescription drugs to overall fee-for-service Medicare spending by excluding spending on drugs administered in the inpatient setting, under prospective payment systems, or for select high-cost services. Because the contribution of drugs relative to other services is unknown, the absence of these amounts from estimates of total drug spending reflects a conservative approach.

Third, services were broadly categorized under 1 of the 3 “parts” of the fee-for-service Medicare program (Part A, B, or D). Some services, such as Home Health, may be reimbursed through either Part A or Part B, so estimates of spending by component may vary from other published estimates.

Fourth, the period of observation was 2008 through 2019. Whether spending patterns observed in 2019 are similar to those in more recent years is not clear, such as patterns of drug spending during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a recent analysis found that, despite an approximate 6% decline in Part A and B Medicare spending in 2020 for fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, Part B drugs were 1 of only 3 service types that had higher spending relative to 2019 (Part D drugs were not included in that analysis).29 Furthermore, a recent Supreme Court ruling found that reductions of Medicare reimbursement (from the average sales price plus 6% to the average sales price minus 22.5%) for drugs dispensed in 340B participating hospitals were unlawful and these funds must be repaid to hospitals.30 It is estimated that Medicare reduced payments by more than $1 billion per year in 2018 and subsequent years, which would lower the estimated spending in these years relative to future years, although current data on these payments for 2022 are not available.

Conclusions

In 2019, spending on prescription drugs represented approximately 27% of total spending among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part D, even after accounting for postsale rebates.

eTable 1. Enrollment by Year and Sample Loss With Restriction

eTable 2. Per Capita Spending by Service Category in Fee-for-Service Medicare, 2008-2019

eTable 3. Fee-for-Service Medicare Spending by Component Among Beneficiaries Enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B, and No Medicare Advantage

References

- 1.Hernandez I, San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, Gellad WF. Changes in list prices, net prices, and discounts for branded drugs in the US, 2007-2018. JAMA. 2020;323(9):854-862. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rome BN, Egilman AC, Kesselheim AS. Trends in prescription drug launch prices, 2008-2021. JAMA. 2022;327(21):2145-2147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.5542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kesselheim AS, Avorn J, Sarpatwari A. The high cost of prescription drugs in the United States: origins and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2016;316(8):858-871. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dusetzina SB, Huskamp HA, Rothman RL, et al. Many Medicare beneficiaries do not fill high-price specialty drug prescriptions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(4):487-496. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandra A, Flack E, Obermeyer Z. The Health Costs of Cost Sharing: Working Paper 28439. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Making Medicines Affordable . A National Imperative. National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin AB, Hartman M, Washington B, Catlin A. National health care spending in 2017: growth slows to post-Great Recession rates; share of GDP stabilizes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38:101377hlthaff201805085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartman M, Martin AB, Washington B, Catlin A; The National Health Expenditure Accounts Team . National health care spending in 2020: growth driven by federal spending in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(1):13-25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Therapeutic drug use. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/drug-use-therapeutic.htm

- 10.Congressional Budget Office. Prescription drugs: spending, use, and prices. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57772

- 11.Mathews JE. Payment policy for prescription 10 drugs under Medicare Part B and Part D: statement of James E. Mathews, PhD, executive director, Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, before the Subcommittee on Health, Committee on Energy and Commerce, US House of Representatives. April 30, 2019. Accessed September 20, 2022. https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/import_data/scrape_files/docs/default-source/congressional-testimony/04_30_2019_medpac_drug_testimony_for_eandc.pdf

- 12.Cubanski J, Rae M, Young K, Damico A. How does prescription drug spending and use compare across large employer plans, Medicare Part D, and Medicaid? Kaiser Family Foundation. May 20, 2019. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/how-does-prescription-drug-spending-and-use-compare-across-large-employer-plans-medicare-part-d-and-medicaid/

- 13.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission . March 2022 report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. March 15, 2022. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://www.medpac.gov/document/march-2022-report-to-the-congress-medicare-payment-policy/

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2022 ASP drug pricing files. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-part-b-drug-average-sales-price/2022-asp-drug-pricing-files

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Addendum A and addendum B updates. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalOutpatientPPS/Addendum-A-and-Addendum-B-Updates

- 16.Board of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds . 2021 Annual report of the boards of trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2021-medicare-trustees-report.pdf

- 17.Dunn A, Grosse SD, Zuvekas SH. Adjusting health expenditures for inflation: a review of measures for health services research in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(1):175-196. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cubanski J, Damico A. Key facts about Medicare Part D enrollment, premiums, and cost sharing in 2021. Kaiser Family Foundation. June 8, 2021. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/key-facts-about-medicare-part-d-enrollment-premiums-and-cost-sharing-in-2021/

- 19.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation . Medicare Part B drugs: trends in spending and utilization, 2006-2017. November 19, 2020. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/medicare-part-b-drugs-trends-spending-utilization-2006-2017 [PubMed]

- 20.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission . June 2022 report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system. June 15, 2022. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://www.medpac.gov/document/june-2022-report-to-the-congress-medicare-and-the-health-care-delivery-system/

- 21.Anderson KE, Polsky D, Dy S, Sen AP. Prescribing of low- versus high-cost Part B drugs in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. Health Serv Res. 2022;57(3):537-547. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Afendulis CC, He Y, Zaslavsky AM, Chernew ME. The impact of Medicare Part D on hospitalization rates. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(4):1022-1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01244.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayyagari P, Shane DM, Wehby GL. The impact of Medicare Part D on emergency department visits. Health Econ. 2017;26(4):536-544. doi: 10.1002/hec.3326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doshi JA, Li P, Huo H, Pettit AR, Armstrong KA. Association of patient out-of-pocket costs with prescription abandonment and delay in fills of novel oral anticancer agents. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(5):476-482. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.5091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, Johnsrud M. Patient and plan characteristics affecting abandonment of oral oncolytic prescriptions. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17 Suppl 5 Developing:SP38-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gokhale M, Dusetzina SB, Pate V, et al. Decreased antihyperglycemic drug use driven by high out-of-pocket costs despite Medicare coverage gap closure. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(9):2121-2127. doi: 10.2337/dc19-1880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan C, Zhang Y. The January effect: medication reinitiation among Medicare Part D beneficiaries. Health Econ. 2014;23(11):1287-1300. doi: 10.1002/hec.2981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, HR 5376, 117th Cong (2021-2022).

- 29.Fuglesten Biniek J, Cubanski J, Neuman T. Traditional Medicare spending fell almost 6% in 2020 as service use declined early in the COVID-19 pandemic. June 1, 2022. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/traditional-medicare-spending-fell-almost-6-in-2020-as-service-use-declined-early-in-the-covid-19-pandemic

- 30.Reed A. Hospitals demand fast repayment for Medicare drug program cuts. Bloomberg Law. August 4, 2022. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/hospitals-demand-fast-repayment-for-medicare-drug-program-cuts

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Enrollment by Year and Sample Loss With Restriction

eTable 2. Per Capita Spending by Service Category in Fee-for-Service Medicare, 2008-2019

eTable 3. Fee-for-Service Medicare Spending by Component Among Beneficiaries Enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B, and No Medicare Advantage