Abstract

In this work, we present a wireless ultrasonic neurostimulator, aiming at a truly wearable device for brain stimulation in small behaving animals. A 1D 5-MHz capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducer (CMUT) array is adopted to implement a head-mounted stimulation device. A companion ASIC with integrated 16-channel high-voltage (60-V) pulsers was designed to drive the 16-element CMUT array. The ASIC can generate excitation signals with element-wise programmable phases and amplitudes: 1) programmable sixteen phase delays enable electrical beam focusing and steering, and 2) four scalable amplitude levels, implemented with a symmetric pulse-width-modulation technique, are sufficient to suppress unwanted side-lobes (apodization). The ASIC was fabricated in the TSMC 0.18μm HV BCD process within a die size of 2.5 × 2.5 mm2. To realize a completely wearable system, the system is partitioned into two parts for weight distribution: 1) a head unit (17 mg) with the CMUT array, 2) a backpack unit (19.7 g) that includes electronics such as the ASIC, a power management unit, a wireless module, and a battery. Hydrophone-based acoustic measurements were performed to demonstrate the focusing and beam steering capability of the proposed system. Also, we achieved a peak-to-peak pressure of 2.1 MPa, which corresponds to a spatial peak pulse average intensity (ISPPA) of 33.5 W/cm2, with a lateral full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 0.6 mm at a depth of 3.5 mm.

Keywords: capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducer (CMUT), neurostimulation, ASIC, ultrasound, freely behaving animals, brain stimulation

I. Introduction

ADVANCES in various neurostimulation techniques such as optical stimulation [1] and ultrasonic stimulation as well as traditional electrical stimulation, provide powerful tools to study brain function in neuroscience. Among them, focused ultrasound (FUS) has emerged with the promise of being minimally invasive and safe, while providing a high spatial and temporal resolution.

Researchers have investigated the effects of FUS on neuronal activities in small animals before translation to clinical trials [2], [3]. However, FUS systems in common use are mostly bulky and tethered, requiring the experimental animals to be anesthetized or affixed to a frame, limiting observations of neural activity during behavior. Moreover, the current US stimulation methods mostly rely on single transducers with limited capabilities in focusing and steering the US beam, thereby requiring mechanical translation of the transducer to target different regions. This poses severe limitations on experimenting on small animals, especially when freely moving. Recent studies [4], [5] demonstrated wearable neurostimulation devices consisting of a fixed-focus transducer, resulting in a stimulation area that cannot be dynamically changed on demand. Moreover, the transducers are still tethered to external benchtop electronics, which are essential to provide power and excitation signals.

Programmable features are highly desired in ultrasound systems for having flexibility in the signal pattern generation, allowing neuroscientists to try various patterns and sequences of sonication for stimulation [6]. Static sonication on a single focal spot can give researchers great insights into the mechanism of neural networks. However, it is also essential to sonicate different brain regions by dynamically changing the focus and the duration of sonication, while monitoring the effects of the overlaps between the focal spots, and the sequence of the sonicated regions on the behavior of an experimental animal [7].

In this study, we set out to design and develop a highly-programmable wearable ultrasonic brain stimulator for small animals. The system is based on a 1D capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducer (CMUT) array with a frontend application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) that can steer and focus beams electronically. This paper extends our earlier conference proceedings paper on the same topic by exploring system-level design concepts in greater detail and by presenting additional measurements of IC-level characteristics [8].

Fig. 1 depicts the envisioned application of our wireless ultrasonic neurostimulator proposed in this study. While still having a small form factor, the ultrasonic stimulation system is entirely wireless, and capable of dynamically stimulating different target regions on a 2D plane. In Section II, the beam pattern of a 1D array is simulated and its implications for a small animal brain are discussed. The optimization of the design parameters, such as the number of elements and the number of quantization levels for both phase delays and pulse amplitudes of the 1D array is also discussed in Section II. Section III describes the system architecture of the proposed wearable neurostimulator. The operation of the ASIC that is specifically designed for the 1D CMUT array is provided in this section. The assembly with a power management unit and a Bluetooth Low-Energy (BLE) module is discussed in Section III as well. Section IV presents the electrical characterization and the acoustical measurements of the presented system, focusing on the beam quality, acoustic intensity, and beam steerability.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual diagram of a wearable brain stimulator.

II. Ultrasonic Phased-Array Design

The cerebellum in a rat brain is an ideal target to study the underlying mechanism of neuromodulation methods because the cerebellar nuclei (CN) have direct and indirect connections with many brain regions that govern diverse motor control and cognitive functions. However, the CN, located deep in the brain, is challenging to reach without disturbing the cells along the path, on top of significant attenuation loss. Instead, the Purkinje cells (PCs) that control the activity in the CN is an easier substitute target, located near the cortical surface [12]. Fig. 2(a) shows the coronal section (Interaural −1.68 mm) of a rat (290 g) brain with the region of interest colored in red. The target region is approximately 3.3-mm wide and located at 2-mm depth from the surface.

Fig. 2.

(a) Schematic coronal section (Interaural −1.68 mm) of a rat brain adapted from [9] with a 1D transducer phased array for ultrasonic brain stimulation. (b) Beam profile of a 1D linear transducer array created by using Field II (an ultrasound systems simulation tool) [10], [11].

The primary goal of this study in terms of beam quality is to achieve a sub-mm resolution at a depth of 5 mm, sufficient to reach the region of interest. In general, the specificity of a beam is defined by the full width half maximum (FWHM). For a 1D rectangular array shown in Fig. 3, the FWHM is calculated as

| (1) |

where z is the axial depth from the surface of the array, λ is the wavelength, and D is the aperture size [13]. To achieve a narrower FWHM, one can choose either a large aperture (D ↑) with low frequency (λ ↑) or a smaller aperture (D ↓) with high frequency (λ ↓). This study chose the latter using a center frequency of 5 MHz—higher frequency than commonly used ultrasound frequency (<1 MHz)—because it is hard to achieve a sub-mm resolution with such low frequency, while meeting the small-aperture requirement for a small-animal’s head [3]. In addition, when the transmittance through the water-skull-tissue interface considered, [14] reports that the center frequencies around 2 and 5 MHz show superior transmittance performance. For our study using a phased array, smaller aperture operating at high frequency helps to mitigate refraction loss for a phased array because the incident angles of the beams from elements near the edges are reduced. Also at higher frequencies the focal spot size in the axial direction is smaller as it scales linearly with the wavelength. Rat skull is thin enough to allow sufficient through-transmission at 5 MHz.

Fig. 3.

1D linear array configuration

A conceptual diagram demonstrating ultrasonic beam steering with a 1D transducer array, and its cross sectional beam profile in 3D space are depicted in Fig. 2(a) and (b), respectively. As shown in Fig. 2(b), one of the drawbacks of the 1D array is that it can steer a beam only in the azimuthal direction. Steering and focusing in both the azimuthal and the elevational directions require a 2D array. Also, the beamwidth in the elevational direction is relatively wide, compared to that in the azimuthal direction. The beam in the elevation direction is not focused, which can be overcome by adding an acoustic lens, if needed [15]. In this study, we focus on electronic steering and focusing primarily in the azimuthal direction using a 1D phased array.

A. 1D Array Design Parameters

Fig. 3 describes the configuration of a 1D array and the parameters used in the following simulation are listed in Table I. Note that a 5-MHz CMUT array is used for high spatial resolution, but this could lead to a higher attenuation through the skull [3], which can be compensated by applying a larger AC excitation signal.

TABLE I.

Physical Dimensions and Design Parameters for a 1D Array

| Name | Dimension | Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| # of Elements | elNum | 16 | |

| Element width | elWidth | 0.14 | mm |

| Pitch | elPitch | 0.15 (=λ/2) | mm |

| Kerf | elKerf | 0.01 | mm |

| Element length | elLength | 3.59 | mm |

| Aperture size | D | 2.40 | mm |

| Operating frequency | fC | 5 | MHz |

| Wave length | λ | 0.30 | mm |

| Natural focus A1 | D2/4λ | 4.8 | mm |

| Natural focus E2 | elLength2/4λ | 10.7 | mm |

Natural focus for the width-wise aperture.

Natural focus for the length-wise aperture.

The pitch of an array must be less than λ/2, the spatial Nyquist sampling period for a given aperture, to prevent grating lobes. Substituting D with elNum·λ/2 in (1) requires that the number of elements (elNum) should be > 12 to achieve a sub-mm resolution at z = 5 mm.

Also, to set a natural focus at around 5 mm, elNum should be > 16. For example, the natural focus for elNum = 16 is computed to be about 4.8 mm, beyond which the beam diverges. For an electronically focused array, this sets the maximum range for effective focusing.

B. Generating AC Excitation Signals: Pulse Width Modulation

Apodization is a technique to suppress sidelobes by applying varying amplitudes tapering toward the edges, across the aperture of a transducer. To generate varying amplitudes across the elements of an array, a front-end IC that drives the transducer needs to have the capability to modulate the amplitude of an excitation signal. The modulation of amplitude can be implemented in the voltage domain or in the time domain. The modulation in the voltage domain [Fig. 4(a)] requires a reference voltage generator, typically implemented with high-voltage devices, rendering itself challenging to be realized in each element [16].

Fig. 4.

(a) Pulse amplitude modulation. (b) Conventional pulse width modulation (PWM). (c) Three-level symmetric PWM.

On the other hand, the time-domain modulation is preferably advantageous since it is easier to implement with a few extra digital logic circuit blocks added to the existing circuitry implemented for the phase delays. The simplest form of the time domain modulation is the conventional pulse width modulation (PWM) [Fig. 4(b)]. However, the conventional PWM is not adequate for phased-array systems because the modulated pulse width affects both the average amplitude and the phase of the carrier, in fact, in a nonlinear fashion [17]. On the contrary, the three-level PWM [Fig. 4(c)], sometimes called RF-PWM [17] or bandpass-PWM [18], does not modulate the phase while the pulse width of the carrier is modulated because the centers of symmetry for the varying pulse widths are aligned.

In this study, the three-level PWM was adopted while its pulse width is incrementally varied using finite sets of multiphase pulses. The number of amplitude-quantization levels (QA) is finite as the number of the phase-quantization levels (Qϕ). Fig. 4(c) shows the three-level PWM waveforms quantized in the time domain. To find the relationship between QA and Qϕ, we can consider only a half cycle because of the symmetry between the upper part and the lower part of the PWM. In a half cycle, a set of unique pulses having widths of {1, 3, 5, ..., Qϕ/2 − 3, Qϕ/2 − 1} can be generated, in other words,

| (2) |

C. Quantization Levels of Aperture, Phase Delays, and Amplitudes

To determine how many array elements and quantization levels are needed for both the phase delays and amplitudes of the excitation signals (continuous wave), Field II, an ultrasound systems simulation tool [10], [11], was extensively used.

First, as shown in Fig. 5(a), it is clear that for a fixed pitch an array with a larger number of elements shows better performance in both the axial and the lateral extent of the beam. As discussed in Section II-A, at least 16 elements are required to achieve the sub-mm resolution at a depth of 5 mm and the natural focus at around 5 mm. However, a 16-element array was chosen over a 32-element array in order to operate the ASIC at as low a junction temperature as practical. If a duty cycle of 25% (25% pulsing and 75% idle) is assumed, the average power consumption of the ASIC can easily reach up to 0.72 W and 1.44 W for the 16-element and 32-element arrays, respectively, which are mainly the power (CV 2f) used for charging the capacitance (∼10 pF) of a 1D CMUT element. If an approximate thermal resistance of 90°C/W for the 2.5 × 2.5 mm2 die size is assumed [19], the junction temperature could exceed the safe limit (150°C) [20]. Although active cooling or passive heat-sinking can be used to alleviate this issue, both solutions would increase the size and complexity of the system. Thus, the 16-element array was chosen for the given silicon die area of the ASIC. Still, the aperture size of the 16-element array is large enough for small animal brains. In case a larger number of elements is needed, combining multiple chips can be considered, an approach easily accomplished by daisy-chaining multiple ASICs.

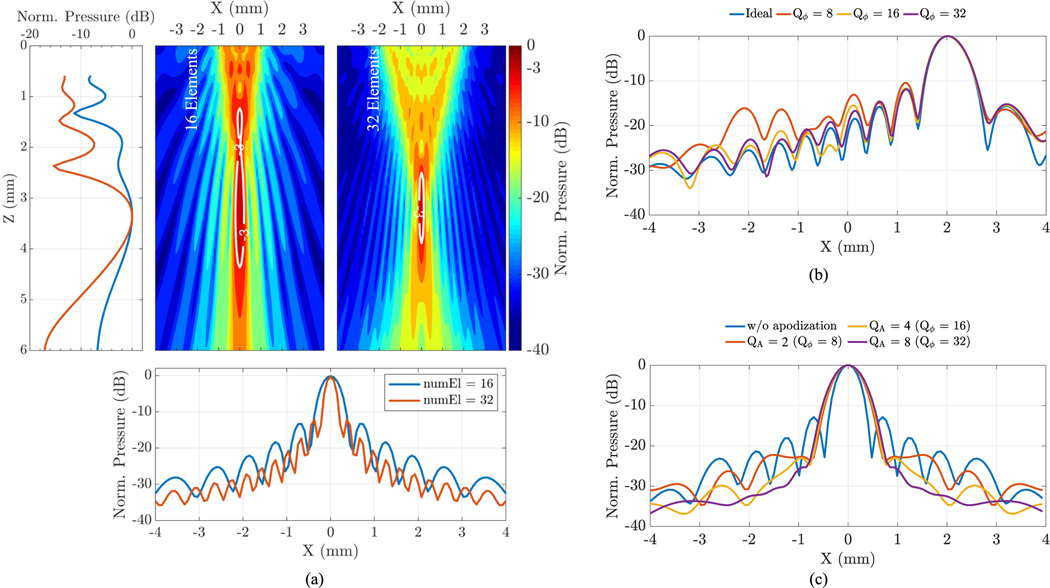

Fig. 5.

(a) Beam patterns and profiles, comparing a 16-element array with a 32-element array. (b) Beam profiles along the azimuthal (X) direction for various phase-quantization levels (Qϕ) of phase delays, when beams are steered in the azimuthal direction by +30°.“Ideal” means “non-quantized”. (c) Beam profiles along the azimuthal (X) direction for various amplitude-quantization levels (QA), when beams are focused at the center with Hanning apodization.

Second, it is essential to quantize the phase delays and the pulse amplitudes. For beamforming, individual transducer elements are driven with AC excitation signals with different delays—time delays for a short pulse or phase delays for a continuous wave (CW)—such that the acoustic waves interfere constructively at a focus. In the digital domain, only a set of finite delays are allowed, thereby requiring quantization. The simulation result [Fig. 5(b)] shows that the quantization lobes manifest themselves when the phase-quantization level (Qϕ) is less than 16, especially when the beam is steered.

Scaling the amplitudes can be implemented at the device level [21] or varying the amplitudes of the applied excitation signals; we chose the latter for this study. As shown in Fig. 5(c), Qϕ of 16, which corresponds to QA of 4, is a reasonable choice, suppressing the sidelobes significantly. Consequently, a 16-element CMUT array with 16 phase delays and 4 amplitude levels was used in this study.

III. System Architecture

This section presents a detailed description of the proposed neural stimulator, focusing on the electronic circuits that include a custom ASIC, a power management unit, and a wireless communication module.

To implement a small-animal wearable device, there are several requirements to be addressed: (1) a custom pulser ASIC for low power consumption and a small footprint, (2) a power management unit that generates all the required voltages from a single battery source, (3) wireless communication via which the system can be dynamically controlled by a host PC, and (4) smart partitioning of the system to render it wearable for small animals.

Fig. 6 shows the architecture of the proposed wearable ultrasonic neural stimulator, consisting of mainly two parts: (1) a head unit on a flexible printed circuit board (FPCB) with a wire-bonded 16-element 1D CMUT array, and (2) a backpack unit that includes a custom 16-channel pulser ASIC, a power management unit, a lithium polymer (LiPo) battery, and a Bluetooth Low-Energy (BLE) enabled microcontroller unit. The one-piece long FPCB with the head unit is directly connected to the backpack unit.

Fig. 6.

Architecture of the proposed neurostimulator.

A. Front-End ASIC

We designed a custom pulser ASIC tailored to the 1D multi-element CMUT array, based on a first-generation ASIC demonstrated in [22], [23]. However, the maximum AC excitation voltage available from the first-generation ASIC was only 13.5 VPP, which was limited by the IC process technology (TSMC 0.35-μm DDD process) used, resulting in a low output pressure level. In this study, we switched to a high-voltage (60 V) BCD process to fully utilize the capability of the CMUT array that had a collapse voltage of 40 V [24]. In addition, problems such as the non-uniformity in phase delays and the non-50% duty cycle discovered in the first-generation ASIC had been addressed in this new ASIC.

The ASIC is comprised of 16 identical pulser units and a global delay-locked loop (DLL). The pulser drives a transducer element with a HV AC excitation signal derived from a low-voltage signal. The carrier frequency (fC) of the excitation signal should be matched to the center frequency of the CMUT for maximum transduction efficiency. The pulsers can be programmed such that the individual excitation signals have different phases for beamforming. A 16-stage voltage-controlled delay line (VCDL) was employed to generate the multiphase clocks instead of using a clock frequency 16× higher than fC, and a counter [25]. This clocking scheme was adopted because the high-frequency clock (fC ×16 = 80 MHz) distributed outside the ASIC could interfere with the BLE connectivity, causing unexpected drops of connection. Also, the power consumption of on-chip clock drivers can be kept low by limiting the frequency, especially for massively arrayed systems. For the global DLL, we adopted an analog-type DLL based on current-starved delay lines [26]. The DLL provides the control voltage for the VCDLs in the elements. The DLL locks 16 identical delays (td) generated by a replica VCDL to a period (tp = 1/fC) of the carrier. This DLL-based topology is independent of the input frequency for generating the phase delays, such that it is adaptable to a CMUT having a different resonant frequency—in the range of 1–10 MHz.

These multiphase clocks are used to configure a pulse train pattern programmed with an 8-b shift register via a serial interface. The description of the 8-b register is summarized in Table II. The generated pulse train is then fed to the high voltage level shifter (HVLS) that drives the HV output stage.

TABLE II.

Description of the 8-b Register in an Element

| Register Name | Description |

|---|---|

|

| |

| EN | 0: Disable the pulser |

| 1: Enable the pulser | |

| PLM | 0: Pulse width modulation (PWM). |

| 1: Pulse level modulation (PLM). | |

| LEVEL < 1 : 0 > | 00–11 (4 levels) in PWM mode. |

| 1X: full swing; 0X: half swing in PLM mode. | |

| PHASE < 3 : 0 > | 0000–1111: 16 phases |

In this study, a three-level output stage was adopted mainly for implementing the three-level PWM, while the power consumption of the output stage itself is reduced because of charge recycling [27]–[29]. The output stage is realized with four switches (MP1, MN1, MP2 and MN2) and two diodes (DP2 and DN2). MP1 and MN1 are used as switches for the transitions: VMP (30 V) → VPP (60 V) and VMP (30 V) → VNP (0 V), respectively, while MP2 and MN2 are used for VNP (0 V) → VMP (30 V) and VPP (60 V) → VMP (30 V), respectively. DP2 and DN2—junction diodes implemented with off-state MOS transistors with their gates connected to their sources—are used to prevent MP2 and MN2 from turning on, respectively, when they are not supposed to be on. For example, when MP2 is off with its gate and source tied to VMP (30 V), and OUT is VPP (60V), the reverse-biased diode (DP2) cuts off the path from OUT (60 V) to the drain of MP2, preventing leakage through the junction of the drain and the body of MP2.

1). Pulse shaper:

The pulse shaper is the core block that determines the overall shape of a pulse train. Fig. 7(a) depicts the detailed block diagram of the pulse shaper. The primary function of the pulse shaper is to generate the switch control signals—SNH, SPM, SPH and SNM for MN1, MP2, MP1 and MN2, respectively—so that the output stage generates an HV AC excitation signal, which can be configured to have five different amplitude levels and sixteen different phase delays.

Fig. 7.

(a) Schematic diagram of the pulse-shaping block. (b) Two-stage barrel shifter. (c) Principles of the pulse width modulation. (d) Timing diagram for generation of a three-level pulse.

Fundamentally, the amplitude modulation (PWM) and the phase-delay configuration are achieved by selecting two signals (P and Pd) from the 16 multiphase signals generated by the VCDL: (1) the delayed signal (P) is chosen according to PHASE<3:0>, which determines the amount of phase delay, and (2) Pd is another delayed signal—the delay of which is determined by LEVEL<1:0>—with respect to P for the pulse width modulation. It is worth noting that the linearly increasing pulse width does not necessarily mean a linearly increasing amplitude. The selection logic for SELA<15:0>, the transmission-gate (TG) control signals for P, is a simple 4-to-16 decoder implemented with pass-gate logic circuits. SELB<15:0>, the TG control signals for Pd, are generated by the two-stage barrel shifter/rotator. This barrel rotator shifts SELA<15:0> to the left by the predefined amount (7b), and then to the right by 2×LEVEL<1:0>. The detailed diagram showing the interconnects inside the barrel shifter is shown in Fig. 7(b).

Fig. 7(c) shows how the PWM signal is generated according to LEVEL<1:0>. After a clock from the multiphase clocks is chosen for P based on PHASE<3:0>, another clock (Pd) is selected, which is delayed by

| (3) |

with respect to P. It should be noted that additional delays— LEVEL < 1 : 0 >·td—must be added to P such that the pulse trains for different levels align at the same center of symmetry [30]. This addition of the offset delay can be software-defined or implemented with another two-stage barrel shifter/rotator [22]. Once P and Pd are selected, the gate control signals (SNH, SPM, SPH and SNM) are generated by combinational logic [Fig. 7(d)]. The non-overlapping clock generator (NOC) is adopted for P and Pd to avoid shoot-through current at the output stage.

2). High-voltage level shifter:

The level shifter is one of the critical components of the HV pulser. The most common type of a level shifter is a digital-style level shifter with an input differential pair and a pair of cross-coupled transistors at the high side [31]. However, because of the large voltage difference between the low voltage (VDD5, 5 V) and the high voltage (VPP, 60 V), this digital-style level shifter is not adequate for high-speed, high-voltage level shifting. Another popular type of a level shifter is a level shifter with a resistor load in parallel with a Zener diode [32]. The structure of the resistor-load level shifter is very simple, but it draws static current when turned on, which can be translated into significant power consumption because the current is drawn from a high voltage power supply (e.g., 60 V). The considerable power consumption becomes worse when the resistor value needs to be reduced for high-speed switching. However, this static current should not be a problem for pulse-echo imaging applications, where transmitting only a short pulse is necessary.

Because neural stimulation needs quasi-continuous-wave (CW) excitation, any static current draw should be avoided as much as possible. In addition to minimal power consumption, the level shifter should be sufficiently fast to handle a switching time of 12.5 ns, which is one sixteenth of 200 ns (1/fC). Therefore, the latch-type level shifter triggered by a short pulse [33], [34] is adopted for the proposed ASIC (Fig. 8). The main advantage of using this topology is that there is a current flow only for a short period, for both the rising and the falling edges of a pulse. The edge is detected by the diode-connected PMOS transistors and latched by the cross-coupled inverters. This type of a level shifter is very fast because the diode-connected load—accepting the current from the input pair—at the drain of the 60-V transistor always has a low impedance. Also, instead of using the HV transistors for the input differential pair, as in [34], cascading the devices is a better choice for high-speed operation. The preceding low-voltage logic sees the small gate capacitance of the differential pair implemented with the low voltage transistors. Also, the fully differential signaling renders the level shifter immune to power supply ringing and improves the common-mode noise injection from the substrate [33], which are critical for an IC, especially when accommodating many switching output stages as in the presented ASIC. Unless the disturbance is adequately addressed, the latching state can change unexpectedly, leading to other problems such as short circuits and abnormal pulse shape. Additionally, decoupling capacitors constructed with an array of 5-V tolerant metal-insulator-metal (MIM) capacitors, were heavily placed over the active circuits, between the main supply and the floating power supply, without consuming additional silicon-die area. It is also worth noting that the use of only two separate n+ buried layers (NBLs), NBL1 and NBL2, benefits area reduction because large space, in general, is required between NBLs for some HV devices.

Fig. 8.

High-voltage level shifter

Fig. 9 shows the die photo of the ASIC fabricated in the TSMC 0.18-μm HV BCD process, within a size of 2.5 × 2.5 mm2. The ASIC includes a total of sixteen pulsers, which can be scaled up by daisy-chaining multiple chips.

Fig. 9.

Microphotograph of the ASIC. Adapted from [8].

B. Power Management Unit (PMU)

For a completely wireless system, all the required power supplies must be generated from a single battery source. This is challenging for CMUT-based applications because CMUTs need a HV DC bias and HV AC excitation signals, typically in the range of tens of volts. Furthermore, three extra HV floating power supplies—VPF, VMPF and VMNF—are required for the gate drivers in the IC.

The overall block diagram of the off-chip power management unit (PMU) is described in Fig. 6. We adopted the same hybrid (inductive plus capacitive) programmable boost converter for generating a HV DC bias for the CMUT array as demonstrated in [35]. For creating VPP (60 V) and VMP (30 V), a voltage multiplier in series with a switching boost converter was used [36]. Due to the fixed amount of charge transferred to the doubler stage, this topology is adequate for light loading scenarios such as low duty cycle or low pulse repetition frequency (PRF). It was proved that this topology was capable of providing sufficient power for the experiments presented in Section IV without significant voltage sag. However, how much power the boost converter can deliver remains to be further studied.

The gate drivers for the HV transistors (MP1, MP2 and MN2) require floating power supplies, 5 V below VPP and VMP; and 5 V above VMP. These floating voltages, as shown in Fig. 10, are created by using the transformer-based isolated power supply topology [37], [38]. The circuit shown in Fig. 10(a) provides bipolar outputs, 5 V below and above VMP, while the circuit shown in Fig. 10(b) generates an output of 5 V below VPP. A transformer ratio of 1:1.3 is used to give headroom for the following low-dropout regulators (LDOs). To create accurate voltages 5 V below VMP and VPP, negative LDOs were adopted, the reference voltages of which are higher than the output voltages. Because the 25-V and 55-V floating supplies act as grounds sinking the currents from the 30 V and 60 V, respectively, we chose an LDO with the current-sinking capability (TPS723, Texas Instruments, Dallas, TX) for the negative LDO. The 1.8-V and 3.0-V power supplies generated by linear regulators directly from the battery are fed to the ASIC and the BLE MCU, respectively, while the 5-V power supply for the ASIC is generated by a DC-DC converter.

Fig. 10.

Push-pull drivers for the floating power supplies: (a) VPF, and (b) VMPF and VMNF.

C. Wearable Prototype

Fig. 11 shows the assembled small-animal-wearable device, which looks similar to the rodent-wearable ultrasound system reported in [39], even though the main function of the proposed system is different.

Fig. 11.

Prototype of the wearable neural stimulator, consisting of a head unit and a backpack unit. Adapted from [8].

The proposed wearable device is a completely wireless system controlled by a host PC via the BLE protocol. We used a BLE microcontroller (Simblee, RF Digital Corp, Hermosa Beach, CA) that implements serial communication between the device under test and a host PC [35]. The host PC calculates the amplitude and phase control bits and transfers the data wirelessly using the Bluetooth Generic Attribute Profile (GATT). Then, the BLE microcontroller passes the received data to the ASIC through the serial peripheral interface (SPI). The BLE protocol was chosen for wireless communication because it has sufficient bandwidth with minimal power consumption to transfer 16-bytes in a single packet, the amount of the data required for programming all the 16 channels at once. Not only the BLE module provides a serial peripheral interface (SPI) but also generates TX_EN (transmit enable) and MCLK (the carrier clock) by using the embedded hardware timer.

A 16-element CMUT array was wire-bonded on a single-piece 55-mm-long FPCB, which directly plugs into the controller board (the backpack unit). The backpack unit consists of the ASIC, the PMU, the BLE module, and a LiPo battery. The physical dimensions of the system are summarized in Table III.

TABLE III.

Physical Dimensions and Specifications for the Wearable Neural Stimulator

| Part | Description |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Head Unit | 17 mg in 9 × 5 mm2 |

| Backpack Unit | 19.7 g in 30.5 × 63.5 mm2 |

| FPCB | 55-mm long |

| Wireless Link | Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) |

| Battery | 120-mAh LiPo battery |

IV. Experimental Results

Experiments were carried out in two steps: (1) electrical characterization of the system without a transducer array attached, and (2) acoustic characterization by using hydrophone scans with a 1D CMUT array immersed in vegetable oil. The following experiments were performed with the prototype completely untethered (no external power supplies, and with only wireless control), except TX_EN connected to a data acquisition board for triggering. Here,

A. Electrical Characterization

The TX pulsers can be programmed individually to generate 16 different phases. To validate the phase-delay programmability, the channels from 0 to 15 were programmed to have incrementally increasing delays from 0·td to 15·td with a step of td, where td is a unit delay that equals to one sixteenth of 1/fc. Because the number of parallel channels available on the oscilloscope was limited to four, a single output was acquired at a time with the output waveform synchronized to TX_EN. Fig. 12(a) shows the measured waveforms aligned to the same rising edge of TX_EN. The rising edges of the output square waves align with their designated minor grids spaced by td. Both INL and DNL of the phase delay are within a half LSB, showing that the programmable phase delay is monotonic and linear [Fig. 12(b)]. Moreover, the duty cycle is very close to 50%, a significant improvement compared to the previous-generation IC, which had a duty-cycle distortion problem [22].

Fig. 12.

(a) Output pulses with incrementally increasing phase delays. (b) INL and DNL of the phase delays across the channels. 1 LSB = 12.5 ns.

The other key functionality of the pulser is transmit apodization by exciting the individual elements with different amplitude signals. There are two operation modes for the amplitude modulation: (1) the pulse level modulation (PLM) that utilizes the switches for the middle voltage (VMP), and (2) the three-level symmetric pulse width modulation (PWM). While the PLM mode has only two amplitude levels [Fig. 13(a)], the PWM mode can generate four different amplitude levels [Fig. 13(b)]. The pulses of each level are symmetric with respect to the center of each PWM period, achieved by adding an offset to the phase delay according to the amplitude level, as explained in Section II-A. Also, Fig. 13(b) exhibits that the pulser, including the HVLS, can drive a 9.5-pF//10 MΩ load of the oscilloscope probe (N2873A, Keysight Technologies, Santa Rosa, CA), without significant RC-charging behavior at a high switching speed (1/fc/16 = 12.5 ns). This capacitive load is very close to the value of the capacitance of the 1D CMUT element.

Fig. 13.

Measured waveforms in the two operation modes: (a) the PLM mode and (b) the PWM mode.

Table IV compares this work with the prior-art pulsers. Compared to the other pulsers developed for ultrasonic imaging, which only need a few cycles of pulsing, this work is well suited for high-voltage continuous-wave excitation (e.g. sonication) because the pulse-triggered latch does not consume static current. For the sole purpose of measuring power consumption, the 16 pulsers were driven with a 5-MHz 50-cycle burst at a PRF of 1 kHz. The average power consumption was measured to be 42 mW. The energy dissipation per pulse is 42 mW/(1 kHz × 50 bursts), which is 840 nJ/pulse. For continuous operation, the power consumption per channel can be calculated as (840 nJ/pulse × 5 MHz / 16 channels), resulting in 263 mW/ch. Note that the power consumption, mostly used for charging and discharging the load capacitance, is highly dependent on the load (C), the driving voltage (V2), and the operating frequency (f). The power consumption drastically increases as the number of channels increases but the average power consumption remains in the reasonable range because sonication, in general, adopts duty cycling, which turn the pulser on only for a fraction of the operation time.

TABLE IV.

Comparison with Prior-Art HV Pulsers

| This Work | [27] | [40] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | 0.18-μm HV BCD |

0.18-μm HV CMOSa |

0.18-μm HV BCD |

| Pulse shape | 3-level unipolar | 3-level unipolar | 3-level bipolar |

| Level shifting | Pulse-triggered latch | Cross-coupled latch | Resistor w/Zener diode |

| # of HV FET | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| Operating freq. (MHz) | 5 | 3.3 | 9 |

| Output VPP | 60 | 30 | 60 |

| Load/ch | 1D CMUT 10 pF | 1D CMUT 40 pF | 1D CMUT 18 pF |

| Area/ch (mm2) | 0.2 | 0.33 | 0.167 |

| Power Consumptionb (mW/ch) |

263.4 | 52.4 | 571.7c |

Supports HV MOS devices with 30-V tolerant gate-oxide.

Power consumption is reported for continuous operation. Average power consumption for any use case can be calculated by multiplying this figure with the duty cycle.

Average power (980 μW) with 7-MHz 3-cycle burst at a PRF of 4 kHz is converted to instantaneous power for comparison by .

Fig. 14 shows the power breakdown for the whole system with the 16-element CMUT attached. The average power consumption was measured for 20-cycle 5-MHz burst at PRF = 100 Hz. Assuming the average output voltage of the 120-mAh LiPo battery is 3.3 V, the system with the 31.45-mW average power consumption can continuously operate for up to 12.6 hours. Note that the operating time highly depends on the duty cycle (PRF).

Fig. 14.

Power-consumption breakdown assuming VBattery is 3.3 V. The power consumption of the ASIC was measured with a duty cycling of 20-cycle 5-MHz burst at PRF = 100 Hz (equivalent to a duty cycle of 0.04%).

B. Acoustic Characterization

An acoustic measurement setup, as shown in Fig. 15, was established with the CMUT array (the head unit) submerged in vegetable oil; the CMUT array facing upward was wire-bonded on a single-piece 135-mm long flexible PCB [Fig. 15 inset], which is then connected to the backpack unit, including the ASIC and the other supporting electronics. The flexible PCB has electroless nickel immersion gold (ENIG) finish, which has a thick gold layer suitable for gold-ball wire bonding. The generated pressure was scanned with a hydrophone (HGL-0200, Onda, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), affixed to a three-axis linear stage (PRO165, Aerotech Inc., Pittsburgh, PA). The acquired signal was then sent to a data acquisition (DAQ) board (PCI-5124, National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). The DAQ board was triggered by TX_EN, which has a PRF of 100 Hz and was driven by the on-board clock driver; this connection to the DAQ is only for acoustical characterization purposes, except for which the whole system was operated wirelessly.

Fig. 15.

Acoustic measurement setup.

The linearity of the pulser was measured by applying various PWM levels, from Level 1 to 4. A single CMUT element, DC-biased at 60 V, was driven with a 20-cycle tone burst of the three-level pulses at 5 MHz. Fig. 16 exhibits that the CMUT driven by the PWM pulser is highly linear, meaning that programming amplitudes for transmit apodization can be straightforward, regardless of the inherent nonlinear characteristics of the CMUT.

Fig. 16.

Normalized pressure emitted by a single element for various PWM levels.

Based on the linearity measurement, we performed electronic apodization experiments. A Hanning window with a length of 16 was computed, normalized, and quantized to four levels. Fig. 17 shows the Hanning-window profile of the PWM levels computed for the individual elements. We applied the same 20-cycle 5-MHz tone burst of the three-level pulses—which was scaled according to the calculated apodization profile—with a PRF of 100 Hz. The phase delays for the individual elements were calculated by using the delay-and-sum-algorithm such that the beams were focused to a depth of 5 mm at the center.

Fig. 17.

PWM levels (amplitude scales) for each of 16 CMUT elements for the Hanning-windowed apodization.

The RMS pressure patterns in the XZ plane with and without apodization are shown in Fig. 18(a). Also, the beam profiles of the cross-sections at z = 5 mm, along the X (azimuth) axis are shown in Fig. 18(a). The first side lobe is reduced by 5 dB, with negligible beam broadening for the mainlobe. The 3-dB lateral beamwidth measures 0.6 mm for both cases.

Fig. 18.

Measured beam patterns in the XZ-plane (top) and the cross-sectional plot (bottom) at a depth (z) of 5 mm. (a) Beam patterns with and without apodization. (b) Beam patterns for beams steered by −30°, 0° and +30°. −3-dB contours are delineated with white lines.

To demonstrate electronic beam steering in the active (azimuthal) direction, beam steering experiments were carried out. Fig. 18(b) shows the RMS pressure patterns in the XZ plane and the beam profiles along the X-axis at a depth of 5 mm. The peaks of the steered beams are located near the targets, which are ±30° from the normal, or ± 2.8 mm, which equals to z × tan(30°), on the X-axis, where z is 5 mm. The expected beam broadening due to steering was observed. The peaks of the first sidelobes for all the three cases are approximately 10 dB below their mainlobes.

To find the maximum intensity that the stimulator can provide, we picked the spatial-peak pressure waveform (Fig. 19). The waveform is not symmetric, showing larger positive pressure than the negative pressure. The maximum peak-to-peak pressure occurs at a depth of 3.5 mm, and measures 2.1 MPa, which corresponds to a spatial peak pulse average intensity (ISPPA) of 33.5 W/cm2. The parameters used for calculating the intensity are listed in Table V.

Fig. 19.

Measured A-scan (time series) waveform at a depth of 5 mm.

TABLE V.

Parameters Related to Intensity Calculation

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 3-dB beamwidth1 | 0.6 | mm |

| Density (ρ)2 | 923 | kg/m3 |

| Speed of sound (c)3 | 1468 | ms−1 |

| Peak-to-peak pressure | 2.1 | MPa |

| RMS pressure (Prms) | 0.7 | MPa |

| 33.5 | W/cm2 | |

Lateral beamwidth.

The density of the vegetable oil.

The speed of sound in the vegetable oil.

Table VI shows this work against state-of-art ultrasonic neurostimulators for small behaving animals. The proposed system is completely wireless with the driving system integrated, which benefits from the custom ASIC. We achieved a sub-mm (FWHM = 0.6 mm) resolution by operating the transducer at a high frequency enabled by the in-house-built fine-pitch CMUT array. Also, the system can dynamically focus and steer a beam, potentially enabling various types of sonication. Future works will include in vivo experiments, focusing on modulatory effects induced in the cerebellum in a rat brain.

TABLE VI.

Comparison with State-of-the-Art Ultrasonic Neurostimulators for Behaving Small Animals

| This Work | [5] | [41] | [4] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transducer | 16-element 1D CMUT | 32-element ring CMUT | Single-element PZT | Single-element PZT |

| Operating Frequency | 5 MHz | 183 kHz | 450±8 kHz | 2 MHz |

| Transducer Size | 2.7 mm × 3. 59 mm | 8.1 mm outer 5.2 mm inner diameter |

5-mm diameter | 5-mm diameter |

| Driving System | 0.18-μm HV custom ASIC |

External benchtop | On-board COTS | External benchtop |

| Focusing/Steering | Azimuthanl and axial | Fixed | Fixed | Fixed |

| Driving Voltage | 60VPP | 90VPP | 70VPP | N/A |

| Peak-to-Peak Pressure | 2.1 MPa | 52 kPa | 426 kPa | 2.4 MPa |

| FWHM | 0.6 mm | 2.75 mm | ∼3 mma | 1.2 mm |

| Wireless | BLE control Battery operated |

Tethered | BLE control Battery operated |

Tethered |

| Device Weight | 17 mg (Head Unit) 19.7 g (Backpack Unit) |

0.73 g (Head Unit) | 20 g (Total) | N/A |

| Board Dimension | 63.5 mm × 30.5 mm | N/A | 35 mm × 15 mm | N/A |

| Power Consumption | 31.45 mWb | N/A | 250 mAc from 6–8 V |

N/A |

| In vivo Experiment | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

A width at −6-dB pressure.

Intermittent operation: 20-cycle 5-MHz burst at PRF = 100 Hz.

Continuous sonication.

V. Conclusion

We presented a wearable ultrasonic neural stimulator for chronic implantation in behaving animals that uses a 16-element 1D CMUT array, a front-end ASIC, a PMU, and a BLE module. Through simulation, we showed that quantization levels of 16 for the phase delays and amplitude scaling levels of 4 are optimum for the 16-element transmit phased array without significant loss of performance. Also, we designed a custom ASIC with 16-channel 60-VPP pulsers that implement the phase delays and the amplitude scaling using the pulse width modulation technique. To enable a completely wireless system, we also included a custom-designed on-board PMU that only requires a single LiPo battery as an energy source and a BLE module for wireless communication with a host PC. The assembled system was partitioned into a head unit and a backpack that only weigh 17 mg and 19.7 g, respectively. We conducted electrical characterization of the ASIC, and demonstrated the beamforming and beamsteering capability of the proposed system through hydrophone-based acoustic measurements, while achieving an ISPPA of 33.5 W/cm2—more than the required intensity levels for small animal brain stimulation—and a 3-dB lateral beamwidth of 0.6 mm at a depth of 3.5 mm. This will provide a versatile tool for studying brain function in neuroscience.

Acknowledgment

This work was performed in part at the NCSU Nanofabrication Facility (NNF), a member of the North Carolina Research Triangle Nanotechnology Network (RTNN), which is supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant ECCS1542015) as part of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI).

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grant EY028456.

Biographies

Chunkyun Seok (S’16) received the B.S. degree from KAIST, Daejon, South Korea in 2003, and the M.Eng. degree from Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA in 2005, and the Ph.D. degree from NC State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, in 2020, all in Electrical Engineering.

Chunkyun Seok (S’16) received the B.S. degree from KAIST, Daejon, South Korea in 2003, and the M.Eng. degree from Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA in 2005, and the Ph.D. degree from NC State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, in 2020, all in Electrical Engineering.

From 2005 to 2014, he was with Samsung Electronics, Hwaseong, South Korea, where he focused on designing mixed-signal integrated circuits for portable audio applications and RF transceivers. His current research interests include mixed-signal circuit design for medical ultrasound imaging, low-power sensor interfaces, and ultrasound neural stimulation.

Feysel Yalcin Yamaner (S’99-M’11) received his B.S. degree from Ege University, Izmir, Turkey, in 2004. and the M.S. and Ph.D. degrees from Sabanci University, Istanbul, Turkey, in 2006 and 2011, respectively, all in electrical and electronics engineering. He received Dr. Gursel Sonmez Research Award in recognition of his outstanding research during his Ph.D. study.

Feysel Yalcin Yamaner (S’99-M’11) received his B.S. degree from Ege University, Izmir, Turkey, in 2004. and the M.S. and Ph.D. degrees from Sabanci University, Istanbul, Turkey, in 2006 and 2011, respectively, all in electrical and electronics engineering. He received Dr. Gursel Sonmez Research Award in recognition of his outstanding research during his Ph.D. study.

He was a Visiting Researcher with the VLSI Design and Education Center (VDEC), in 2006. He was a visiting scholar in the Micromachined Sensors and Transducers Laboratory, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA, in 2008. He was a Research Associate with the Laboratory of Therapeutic Applications of Ultrasound, French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) in 2011. He was with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, as a Research Associate from 2012 to 2014. In 2014, he joined the School of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Istanbul Medipol University as an Assistant Professor. He is currently a Research Assistant Professor at North Carolina State University. His research focuses on developing micromachined devices for biological and chemical sensing, ultrasound imaging, and therapy.

Mesut Sahin (M’95-SM’06) received his B.S. degree in electrical engineering from Istanbul Technical University in 1986. After graduation, he worked for a telecommunication company, Teletas A.S., in Istanbul in hardware and software development of phone exchanges until 1990. He received the M.S. degree in 1993 and a Ph.D. degree in 1998 both in biomedical engineering, particularly in the field of neural engineering, from Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio. After post-doctoral training at the same institute, he joined Louisiana Tech University as an Assistant Professor in 2001. He has been on the faculty of Biomedical Engineering at New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, New Jersey since 2005, and currently is a Full Professor, where he teaches bioinstrumentation and neural engineering courses. His research interests are mainly in neural modulation and development of novel neural prosthetic approaches. He has authored more than 90 peer-reviewed publications. Dr. Sahin is an Associate Editor of IEEE Transactions

on Biomedical Circuits

and Systems and a Senior Member of IEEE/EMBS.

Mesut Sahin (M’95-SM’06) received his B.S. degree in electrical engineering from Istanbul Technical University in 1986. After graduation, he worked for a telecommunication company, Teletas A.S., in Istanbul in hardware and software development of phone exchanges until 1990. He received the M.S. degree in 1993 and a Ph.D. degree in 1998 both in biomedical engineering, particularly in the field of neural engineering, from Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio. After post-doctoral training at the same institute, he joined Louisiana Tech University as an Assistant Professor in 2001. He has been on the faculty of Biomedical Engineering at New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, New Jersey since 2005, and currently is a Full Professor, where he teaches bioinstrumentation and neural engineering courses. His research interests are mainly in neural modulation and development of novel neural prosthetic approaches. He has authored more than 90 peer-reviewed publications. Dr. Sahin is an Associate Editor of IEEE Transactions

on Biomedical Circuits

and Systems and a Senior Member of IEEE/EMBS.

Ömer Oralkan (S’93-M’05-SM’10) received the B.S. degree from Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey, in 1995, the M.S. degree from Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, in 1997, and the Ph.D. degree from Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, in 2004, all in electrical engineering.

Ömer Oralkan (S’93-M’05-SM’10) received the B.S. degree from Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey, in 1995, the M.S. degree from Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, in 1997, and the Ph.D. degree from Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, in 2004, all in electrical engineering.

He was a Research Associate and then a Senior Research Associate at the E. L. Ginzton Laboratory, Stanford University, from 2004 to 2007 and from 2007 to 2011, respectively. In 2012, he joined North Carolina State University, Raleigh, where he is currently a Professor of electrical and computer engineering. His current research focuses on developing devices and systems for ultrasound imaging, photoacoustic imaging, image-guided therapy, biological and chemical sensing, and ultrasound neural stimulation.

He has authored over 200 scientific publications. He serves on the Technical Program Committee of the IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium. He received the 2016 William F. Lane Outstanding Teacher Award at NC State, the 2013 DARPA Young Faculty Award, and the 2002 Outstanding Paper Award of the IEEE Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control Society. He is the Editor-in-Chief of IEEE OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF ULTRASONICS, FERROELECTRICS AND FREQUENCY CONTROL.

Footnotes

Preliminary results from this work were presented at the 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society.

Contributor Information

Chunkyun Seok, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, NC State University, Raleigh, NC 27695 USA.

Feysel Yalcin Yamaner, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, NC State University, Raleigh, NC 27695 USA.

Mesut Sahin, Department of Biomedical Engineering, New Jersey Institute of Technology, University Heights, Newark, NJ 07102 USA..

Ömer Oralkan, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, NC State University, Raleigh, NC 27695 USA.

References

- [1].Jia Y, Mirbozorgi SA, Lee B, Khan W, Madi F, Inan OT, Weber A, Li W, and Ghovanloo M, “A mm-sized free-floating wirelessly powered implantable optical stimulation device,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 608–618, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tufail Y, Matyushov A, Baldwin N, Tauchmann ML, Georges J, Yoshihiro A, Tillery SIH, and Tyler WJ, “Transcranial pulsed ultrasound stimulates intact brain circuits,” Neuron, vol. 66, no. 5, pp. 681–694, Jun. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Li G-F et al. , “Improved anatomical specificity of non-invasive neurostimulation by high frequency (5 MHz) ultrasound,” Scientific Reports, vol. 6, p. 24738, Apr. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Li G et al. , “Noninvasive ultrasonic neuromodulation in freely moving mice,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 217–224, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kim H, Kim S, Sim NS, Pasquinelli C, Thielscher A, Lee JH, and Lee HJ, “Miniature ultrasound ring array transducers for transcranial ultrasound neuromodulation of freely-moving small animals,” Brain Stimulation, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 251 – 255, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bystritsky et al. , “A review of low-intensity focused ultrasound pulsation,” Brain Stimulation, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 125–136, Jul. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ye, Peiyong P, Brown JR, Pauly, and Butts K, “Frequency dependence of ultrasound neurostimulation in the mouse brain,” Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology, vol. 42, no. 7, pp. 1512 – 1530, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Seok C, Yamaner FY, Sahin M, and Oralkan Ö, “A sub-millimeter lateral resolution ultrasonic beamforming system for brain stimulation in behaving animals,” in 2019. 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 2019, pp. 6462–6465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Praxinos G and Watson C, The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates: Compact, 6th ed. New York, NY, USA: Elsevier, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jensen JA and Svendsen NB, “Calculation of pressure fields from arbitrarily shaped, apodized, and excited ultrasound transducers,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason., Ferroelectr., Freq. Control, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 262–267, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jensen JA, “Field: A program for simulating ultrasound systems,” The 10th Nordic-Baltic Conference on Biomedical Imaging Published in Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 351–353, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Asan AS, Kang Q, Oralkan O, and Sahin M, “Entrainment of¨ cerebellar purkinje cell spiking activity using pulsed ultrasound stimulation,” Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 598–606, May 2021, publisher: Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Szabo TL, Diagnostic Ultrasound Imaging: Inside Out. Burlington, MA, USA: Elsevier Academic Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Aydin MA, Kilinc MS, Ergun AS, Bozkurt A, and Deveci E, “Ultrasonic transmittance of rat skull as a function of frequency,” in 2016. IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), 2016, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chang C, Firouzi K, Kyu Park K, Sarioglu AF, Nikoozadeh A, Yoon H-S, Vaithilingam S, Carver T, and Khuri-Yakub BT, “Acoustic lens for capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducers,” Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering, vol. 24, no. 8, p. 085007, Aug. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Igarashi Y et al. , “Single-chip 3072-element-channel transceiver/128-subarray-channel 2-D array IC with analog RX and all-digital TX beamformer for echocardiography,” IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, vol. 54, no. 9, pp. 2555–2567, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Song H and Gharpurey R, “Digitally intensive wireless transmitter architecture employing RF pulse width modulation,” in 2014. IEEE Dallas Circuits and Systems Conference (DCAS), 2014, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rosnell S and Varis J, “Bandpass pulse-width modulation (BP-PWM),” in IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest, 2005., 2005, pp. 4 pp.–734. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Instruments Texas, “Semiconductor and IC package thermal metrics,” Application Notes, Apr. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Devices Analog, “Thermal design basics,” Application Notes, Jan. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rasmussen MF, Christiansen TL, Thomsen EV, and Jensen JA, “3-D imaging using row-column-addressed arrays with integrated apodization - part I: apodization design and line element beamforming,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason., Ferroelectr., Freq. Control, vol. 62, no. 5, pp. 947–958, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Seok C, Wu X, Yamaner FY, and Oralkan Ö, “A front-end integrated circuit for a 2D capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducer (CMUT) array as a noninvasive neural stimulator,” in 2017. IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), 2017, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Seok C, Ali Z, Yamaner FY, Sahin M, and Oralkan Ö, “Towards an untethered ultrasound beamforming system for brain stimulation in behaving animals,” in 2018. 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 2018, pp. 1596–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yamaner FY, Zhang X, and Oralkan Ö, “A three-mask process for fabricating vacuum-sealed capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducers using anodic bonding,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason., Ferroelectr., Freq. Control, vol. 62, no. 5, pp. 972–982, May 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Xun Wu, Kumar M, and Oralkan Ö, “An ultrasound-based noninvasive neural interface to the retina,” in 2014. IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, 2014, pp. 2623–2626. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ahmad H and Bakkaloglu B, “A digitally controlled DC-DC buck converter using frequency domain ADCs,” in 2010. Twenty-Fifth Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), 2010, pp. 1871–1874. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chen K, Lee H, Chandrakasan AP, and Sodini CG, “Ultrasonic imaging transceiver design for CMUT: A three-level 30-Vpp pulseshaping pulser with improved efficiency and a noise-optimized receiver,” IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, vol. 48, no. 11, pp. 2734–2745, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Holen AL and Ytterdal T, “A high-voltage cascode-connected threelevel pulse-generator for bio-medical ultrasound applications,” in 2019. IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), 2019, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Muntal PL, Larsen DØ, Jørgensen IHH, and Bruun E, “Integrated differential three-level high-voltage pulser output stage for CMUTs,” in 2015. 11th Conference on Ph.D. Research in Microelectronics and Electronics (PRIME), 2015, pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lee Y, Seok C, Kim B, You S, Yeum W, Park H, Jun Y, Kong B, and Kim J, “A 1.3-mW per-channel 103-dB SNR stereo audio DAC with class-D head-phones amplifier in 65nm CMOS,” in 2008. IEEE Symposium on VLSI Circuits, 2008, pp. 176–177. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bhuyan A, Choe JW, Lee BC, Wygant IO, Nikoozadeh A, Oralkan Ö, and Khuri-Yakub BT, “Integrated circuits for volumetric ultrasound imaging with 2-D CMUT arrays,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 796–804, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Jung G, Tekes C, Rashid MW, Carpenter TM, Cowell D, Freear S, Degertekin FL, and Ghovanloo M, “A reduced-wire ICE catheter ASIC with Tx beamforming and Rx time-division multiplexing,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst., vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 1246–1255, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Høyerby M, Jakobsen JK, Midtgaard J, and Hansen TH, “A 2×70 W monolithic five-level class-D audio power amplifier in 180 nm BCD,” IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, vol. 51, no. 12, pp. 2819–2829, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Liu D, Hollis SJ, Dymond HCP, McNeill N, and Stark BH, “Design of 370-ps delay floating-voltage level shifters with 30-V/ns power supply slew tolerance,” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs, vol. 63, no. 7, pp. 688–692, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Seok C, Mahmud MM, Kumar M, Adelegan OJ, Yamaner FY, and Oralkan Ö, “A low-power wireless multichannel gas sensing system based on a capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducer (CMUT) array,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 831–843, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [36].“High-V DC-DC converter is ideal for MEMS,” Maxim Integrated, App. Note, Sep. 2002. [Online]. Available: https://www.maximintegrated.com/en/app-notes/index.mvp/id/1751

- [37].Instruments Texas, “Transformer driver for isolated power supplies,” SN6501 datasheet, Jul. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Brown A and Lei J, “High Voltage DC/DC converter for Supertex ultrasound transmitter demoboards,” Microchip Inc., App. Note, Jun. 2014. [Online]. Available: http://ww1.microchip.com/downloads/en/Appnotes/AN-H59.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [39].Piech DK, Kay JE, Boser BE, and Maharbiz MM, “Rodent wearable ultrasound system for wireless neural recording,” in 2017. 39th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 2017, pp. 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Tan M, Kang E, An J, Chang Z, Vince P, Matéo T, Sénégond N, and Pertijs MAP, “A 64-channel transmit beamformer with ±30-V bipolar high-voltage pulsers for catheter-based ultrasound probes,” IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, vol. 55, no. 7, pp. 1796–1806, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kim E, Anguluan E, Kum J, Sanchez-Casanova J, Park TY, Kim JG, and Kim H, “Wearable transcranial ultrasound system for remote stimulation of freely moving animal,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, pp. 1–1, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]