Abstract

A 50-year-old woman with persistent axillary lymphadenopathy 17 weeks after COVID-19 vaccination was ultimately diagnosed with biopsy-proven benign reactive lymphadenopathy. In contrast, a 60-year-old woman with axillary lymphadenopathy and concurrent suspicious breast findings 9 weeks after COVID-19 vaccination was ultimately diagnosed with biopsy-proven metastatic breast carcinoma. This article reviews the current guidelines regarding breast cancer screening and management of axillary lymphadenopathy in the setting of COVID-19 vaccination.

© RSNA, 2022

Dr Stacey Wolfson is a current 4th year and chief resident in the Department of Radiology at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine. Next year, she will be staying at New York University to pursue her breast imaging fellowship.

Dr Eric Kim is a clinical assistant professor in the breast imaging section of the Department of Radiology at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine. He completed both his diagnostic radiology residency and fellowship in breast imaging at NYU. His current research interests include artificial intelligence in imaging and the impact of COVID-19 on breast imaging.

Summary

As evidence continues to emerge about axillary lymphadenopathy following COVID-19 vaccination, up-to-date guidelines regarding breast cancer screening and management of axillary lymphadenopathy should be followed to reduce the need for follow-up imaging or biopsy.

Teaching Points

■ Screening mammography should not be delayed following COVID-19 vaccination.

■ Reactive axillary lymphadenopathy after COVID-19 vaccination is estimated to occur in 2.4%–35% of women and may persist for up to 43 weeks, with higher incidence of lymphadenopathy seen in mRNA vaccines versus vector vaccines.

■ Isolated unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy ipsilateral to the side of vaccination without other suspicious imaging findings may be considered benign.

■ More cautious management, including possible biopsy, should be taken for patients with concurrent suspicious imaging findings and those at high risk or with a personal history of breast cancer.

Case Presentation (Dr Stacey Wolfson)

Case 1

A 50-year-old woman with no personal or family history of breast cancer presented for routine screening mammography and US. She had received the first dose of the mRNA-1273 (Moderna) COVID-19 vaccination in her left arm 10 days earlier. Screening US demonstrated two prominent lymph nodes within the left axilla with a thickened cortex measuring 6 mm (Fig 1A, 1B); these lymph nodes were mammographically occult. No other suspicious findings were seen on either mammograms or US scans. The new left axillary lymphadenopathy was thought to be reactive to the recent COVID-19 vaccination. Therefore, the patient’s screening US examination was given a Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category 3 (probably benign) assessment with recommendation for follow-up targeted US in 3 months.

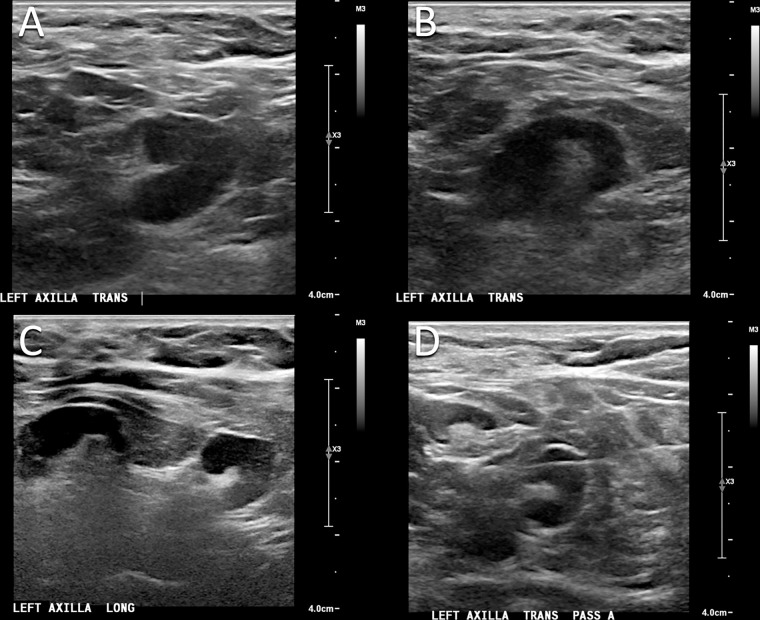

Figure 1:

Images in a 50-year-old woman who presented for routine screening mammography and US 10 days after COVID-19 vaccination in her left arm. (A, B) Screening US scans demonstrate two prominent lymph nodes in the left axilla, with cortical thickening measuring up to 6 mm. (C) Targeted US scan obtained at 3-month follow-up demonstrates persistent lymphadenopathy. (D) US-guided core biopsy was performed, and pathologic examination yielded a benign reactive lymph node without evidence of malignancy.

The patient returned for follow-up targeted US 17 weeks after the second dose of the mRNA-1273 vaccination in the left arm. US demonstrated persistent axillary lymphadenopathy with continued cortical thickening of 6 mm (Fig 1C). Given the persistent lymphadenopathy, the findings were thought to be suspicious (BI-RADS category 4) and US-guided core biopsy was performed (Fig 1D). Pathologic examination yielded a benign reactive lymph node without evidence of malignancy.

Case 2

A 60-year-old woman with no personal or family history of breast cancer presented for routine screening mammography. The patient had received the second dose of the mRNA-1273 (Moderna) COVID-19 vaccination in the left arm 9 weeks earlier. There was a new spiculated mass with associated architectural distortion in the left breast. In addition, a new dense lymph node was incompletely visualized in the left axilla (Fig 2A, 2B). This screening mammogram was given a BI-RADS category 0 assessment (needs additional imaging), and the patient was recalled for further imaging.

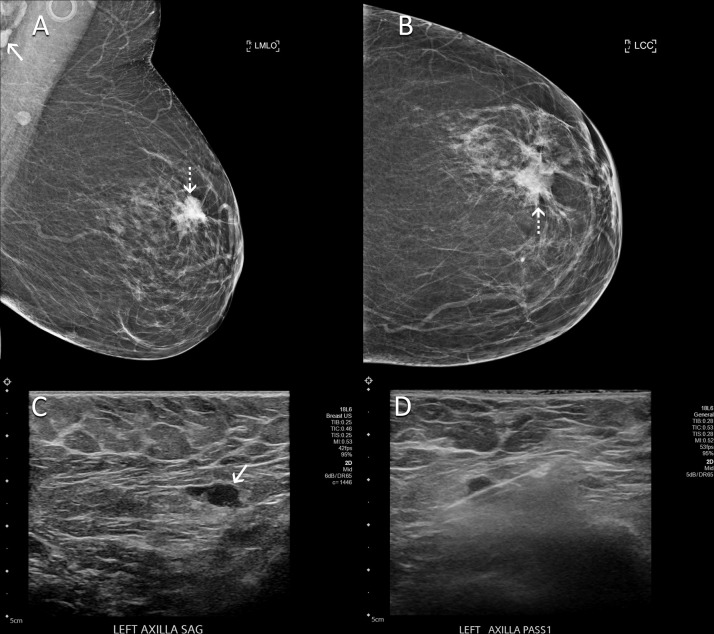

Figure 2:

Images in a 60-year-old woman with no personal or family history of breast cancer who presented for routine screening mammography 9 weeks after COVID-19 vaccination in her left arm. (A) Mediolateral oblique and (B) craniocaudal mammographic views of the left breast demonstrate a new spiculated mass in the left breast (dotted arrows). In addition, a left axillary lymph node (solid arrow in A) had increased in prominence and density in comparison with that seen on her prior mammogram. (C) US scan shows a lymph node with eccentric cortical thickening measuring 6 mm (arrow) in the left axilla. (D) US-guided core biopsy of lymph node yielded metastatic carcinoma.

Five days later, the patient presented for diagnostic mammography and targeted US. Diagnostic evaluation confirmed an irregular mass in the left breast suspicious for malignancy. On US scans, there was an enlarged lymph node in the left axilla with focal cortical thickening measuring up to 6 mm (Fig 2C). Therefore, these findings were highly suggestive of malignancy (BI-RADS category 5) and biopsy was performed for both the breast mass and left axillary lymph node (Fig 2D). Pathologic examination of the breast mass yielded invasive ductal carcinoma with lobular and micropapillary features. Pathologic examination of the lymph node yielded metastatic adenocarcinoma. The patient subsequently underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy.

Case Discussion (Dr Eric Kim)

COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. The World Health Organization officially declared the COVID-19 global outbreak as a pandemic in March 2020 (1). Since then, there have been more than 90 million cases in the United States (2) and over 500 million cases globally (3) at the time of this writing.

The COVID-19 Vaccines

To decrease the risk of severe COVID-19 infection and COVID-19–related mortality, developers created vaccines effective against SARS-CoV-2 infection at an unprecedented pace. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued emergency use authorization for the BNT162b2 (Pfizer BioNTech) mRNA vaccine and the mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccine in December 2020 (4), just 1 year after the first cases of COVID-19 were reported. There are now three COVID-19 vaccines approved for use in the United States, with the JNJ-78436735 (Johnson & Johnson/Janssen) vector vaccine approved in February 2021 (5). Multiple additional vaccines are in use around the world, including the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca) vector vaccine.

Currently, 67% of the world population has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, with more than 12 billion doses administered globally (6). Given widespread vaccination, adverse effects of the COVID-19 vaccines have become well recognized and publicized in the mainstream media. The most common adverse effects are transient and mild, including fatigue, myalgia, headache, chills, injection site swelling or erythema, joint pain, and fever. In contrast, serious adverse effects such as anaphylaxis are rare (7).

Vaccination-related versus Breast Cancer–related Axillary Lymphadenopathy

In radiology, one of the more well-known adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccination is axillary lymphadenopathy, which is the result of a local immune response to the vaccine. When it occurs, it is usually seen in the axilla ipsilateral to the side of vaccine administration. Upon initiation of population vaccine programs, physicians have quickly realized that the vaccine dose administration may cause diagnostic dilemmas, especially in patients receiving breast imaging (8).

Unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy is a suspicious finding due to the possibility of metastatic disease from an underlying breast cancer. In fact, up to 1% of all breast cancers initially manifest as isolated axillary lymph node metastasis even in the absence of other suspicious breast findings at conventional imaging (9). In contrast, bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy is usually benign and due to reactive, infectious, or systemic causes. Understandably, radiologists did not want to miss a possible breast cancer and were uncertain whether unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy in the setting of COVID-19 vaccination could be assessed safely as benign, especially when the incidence and duration of this lymphadenopathy was still unclear.

Several retrospective and prospective studies have now been published, with results suggesting that the incidence and duration of axillary lymphadenopathy following COVID-19 vaccination are greater than originally anticipated. In retrospective studies, the incidence of axillary lymphadenopathy has been reported to range from 2.4% to 35% for women undergoing screening mammography and/or US (10,11). This is in stark contrast to the reported 0.02%–0.04% incidence of axillary lymphadenopathy at screening mammography before the COVID-19 vaccine era (12). In a retrospective study featuring long-term follow-up in 1217 patients who received a COVID-19 vaccine and underwent breast imaging, axillary lymphadenopathy was seen as early as 1 day after vaccination and persisted for up to 43 weeks (10). A recently published prospective study analyzed the temporal changes of axillary lymphadenopathy following COVID-19 vaccination in 88 otherwise healthy women who underwent serial US. They found that 51% of women who had follow-up at 10–12 weeks had persistent lymphadenopathy (13). In both studies, no malignancy was found in asymptomatic patients without suspicious mammographic findings or history of breast cancer. Interestingly, one study demonstrated increased lymphadenopathy and cortical thickness in patients who had received an mRNA vaccine in comparison with those who received the vector-based ChAdOx1 vaccine (14).

Current Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines

Various societies have created guidelines regarding breast cancer screening in patients with recent COVID-19 vaccination. Most agree that in patients with a personal history of breast cancer, vaccination should be performed in the arm contralateral to the side of cancer. For all patients, data including date of administration, dose, injection site, laterality, and type of vaccine should be recorded and available to the interpreting radiologist (12,15,16).

Initial guidelines were relatively conservative, aiming to reduce unnecessary diagnostic work-up and biopsies. For instance, the Society of Breast Imaging (SBI) released recommendations in early 2021 to consider scheduling screening mammography before the first dose of vaccination or 4–6 weeks after the last dose of vaccination (17). The European Society of Breast Imaging guidelines recommended postponing screening for at least 12 weeks after the last vaccination dose (15).

However, updated position statements and studies including the two previously mentioned have now been published. There have also been concerns that the initial delays in breast cancer screening during the pandemic would result in delays in diagnosis and treatment, with a possible negative impact on breast cancer mortality (18). The SBI released revised guidelines in February 2022 based on this new information, no longer recommending delaying screening mammography around the COVID-19 vaccinations (12). This is similar to the approach recommended by Lehman et al (19), who encouraged screening for all patients regardless of vaccination status.

Management of Vaccine-related Axillary Lymphadenopathy

Guidelines for the management of vaccine-related axillary lymphadenopathy have similarly evolved after it had become evident that vaccine-related axillary lymphadenopathy was more common and the duration longer than originally predicted. The SBI initially recommended BI-RADS category 0 (needs additional imaging) assessment for patients with unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy at screening mammography after COVID-19 vaccination. Follow-up imaging at 4–12 weeks was recommended for cases of presumed vaccine-related lymphadenopathy, with biopsy to be considered for any persistent lymphadenopathy at follow-up (17). These initial guidelines were followed for our patient in case 1, who underwent US-guided core biopsy for persistent axillary lymphadenopathy at follow-up imaging 17 weeks after vaccination which yielded benign results.

The revised SBI guidelines now state that it may be appropriate to give a BI-RADS category 2 (benign) assessment without the need for follow-up imaging in patients with recent COVID-19 vaccination and isolated unilateral axillary adenopathy at screening without other suspicious mammographic findings (12). These guidelines are in line with the European Society of Breast Imaging guidelines and Radiology scientific expert panel guidelines that do not recommend default follow-up imaging for low-risk patients without breast cancer history and without suspicious breast imaging findings (15,16). Biopsy may have been avoided in our patient in case 1 if these revised guidelines were available at that time.

For patients who receive short-term follow-up (BI-RADS category 3) for likely vaccine-related adenopathy, a longer follow-up interval of at least 12 weeks is recommended (12,15) rather than the 4–12 weeks previously recommended. At follow-up, benign assessment is recommended if the axillary adenopathy is noted to improve. If the adenopathy appears unchanged, an additional follow-up in 6 months may be performed. If the adenopathy has increased, then biopsy should be considered to exclude malignancy (12).

Special considerations should be made in specific situations. For patients who have axillary adenopathy with suspicious findings in the ipsilateral breast, management should be based on the degree of suspicion of the breast lesion and appearance of adenopathy, with biopsy as possibly appropriate. This scenario was seen in case 2, in which the patient concurrently had a suspicious mass in the ipsilateral breast and was diagnosed with breast cancer metastatic to the axilla. In patients with axillary adenopathy contralateral to the site of vaccination, standard work-up including possible biopsy is recommended (15). In high-risk patients such as those with a personal history of breast cancer, management should depend on the risk of axillary nodal metastasis with possible biopsy in higher risk patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we presented two cases of patients who demonstrated axillary lymphadenopathy following recent COVID-19 vaccination. In the first case, the patient had no concurrent suspicious mammographic findings, relevant cancer history, or risk factors. The patient had persistent lymphadenopathy at follow-up imaging 17 weeks after vaccination, and US-guided core biopsy of her lymph node yielded benign histologic findings. In the second case, the patient concurrently had a suspicious breast mass. Biopsy was performed of both the suspicious breast mass and suspicious lymph node, with both yielding malignancy.

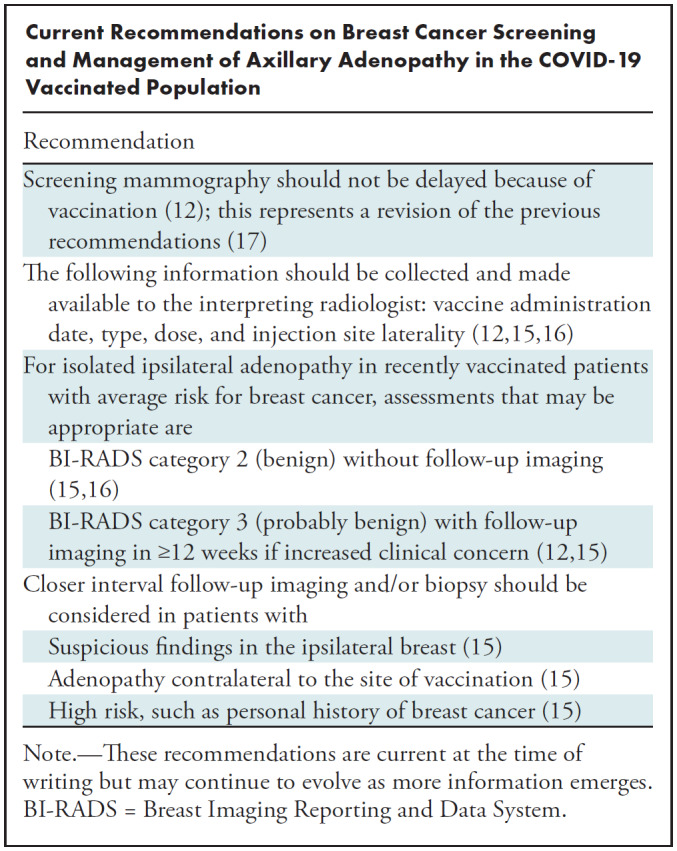

Current guidelines reflect the emerging evidence that axillary lymphadenopathy is seen at higher incidence and of longer duration than originally anticipated (Table). Consequently, the revised guidelines now state that screening mammograms should not be delayed after COVID-19 vaccination. Patients with isolated unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy after COVID-19 vaccination without other suspicious mammographic findings may be given BI-RADS category 2 (benign) assessment without the need for follow-up. However, more cautious management is appropriate for patients with suspicious findings in the breast or those with a high risk or personal history of breast cancer.

Current Recommendations on Breast Cancer Screening and Management of Axillary Adenopathy in the COVID-19 Vaccinated Population

Disclosures of conflicts of interest: S.W. No relevant relationships. E.K. No relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- BI-RADS

- Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System

- SBI

- Society of Breast Imaging

References

- 1. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - March11, 2020 . World Health Organization website . https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19–-11-march-2020. Accessed August 10, 2022 .

- 2. COVID Data Tracker . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website . https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_dailycases_select_00. Accessed August 10, 2022 .

- 3. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard . World Health Organization website . https://covid19.who.int. Accessed August 10, 2022 .

- 4. FDA Takes Key Action in Fight Against COVID-19 By Issuing Emergency Use Authorization for First COVID-19 Vaccine . U.S. Food & Drug Administration website . https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-key-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-first-covid-19. Accessed August 10, 2022 .

- 5. FDA Issues Emergency Use Authorization for Third COVID-19 Vaccine . U.S. Food & Drug Administration website . https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-issues-emergency-use-authorization-third-covid-19-vaccine. Accessed August 10, 2022 .

- 6. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations . Our World in Data website . https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations. Accessed August 10, 2022 .

- 7. Beatty AL , Peyser ND , Butcher XE , et al . Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccine Type and Adverse Effects Following Vaccination . JAMA Netw Open 2021. ; 4 ( 12 ): e2140364 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Özütemiz C , Krystosek LA , Church AL , et al . Lymphadenopathy in COVID-19 Vaccine Recipients: Diagnostic Dilemma in Oncologic Patients . Radiology 2021. ; 300 ( 1 ): E296 – E300 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Görkem SB , O’Connell AM . Abnormal axillary lymph nodes on negative mammograms: causes other than breast cancer . Diagn Interv Radiol 2012. ; 18 ( 5 ): 473 – 479 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolfson S , Kim E , Plaunova A , et al . Axillary Adenopathy after COVID-19 Vaccine: No Reason to Delay Screening Mammogram . Radiology 2022. ; 303 ( 2 ): 297 – 299 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robinson KA , Maimone S , Gococo-Benore DA , Li Z , Advani PP , Chumsri S . Incidence of Axillary Adenopathy in Breast Imaging After COVID-19 Vaccination . JAMA Oncol 2021. ; 7 ( 9 ): 1395 – 1397 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grimm L , Srini A , Dontchos B , et al . Revised SBI Recommendations for the Management of Axillary Adenopathy in Patients with Recent COVID-19 Vaccination . Society of Breast Imaging website . https://www.sbi-online.org/Portals/0/Position-Statements/2022/SBI-recommendations-for-managing-axillary-adenopathy-post-COVID-vaccination_updatedFeb2022.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2022 . [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ha SM , Chu AJ , Lee J , et al . US Evaluation of Axillary Lymphadenopathy Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Prospective Longitudinal Study . Radiology 2022. ; 305 ( 1 ): 46 – 53 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Igual-Rouilleault AC , Soriano I , Elizalde A , et al . Axillary lymph node imaging in mRNA, vector-based, and mix-and-match COVID-19 vaccine recipients: ultrasound features . Eur Radiol 2022. ; 32 ( 10 ): 6598 – 6607 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schiaffino S , Pinker K , Magni V , et al . Axillary lymphadenopathy at the time of COVID-19 vaccination: ten recommendations from the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI) . Insights Imaging 2021. ; 12 ( 1 ): 119 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Becker AS , Perez-Johnston R , Chikarmane SA , et al . Multidisciplinary Recommendations Regarding Post-Vaccine Adenopathy and Radiologic Imaging: Radiology Scientific Expert Panel . Radiology 2021. ; 300 ( 2 ): E323 – E327 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grimm L , Destounis S , Dogan B , et al . SBI Recommendations for the Management of Axillary Adenopathy in Patients with Recent COVID-19 Vaccination . Society of Breast Imaging website . https://splf.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Society-of-breast-imaging-Recommendations-for-the-Management-of-Axillary-Adenopathy-in-Patients-with-Recent-COVID-19-Vaccination-Mis-en-ligne-par-la-Societe-francaise-de-radiologie-le-10-02-21.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2022 .

- 18. Alagoz O , Lowry KP , Kurian AW , et al . Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Breast Cancer Mortality in the US: Estimates From Collaborative Simulation Modeling . J Natl Cancer Inst 2021. ; 113 ( 11 ): 1484 – 1494 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lehman CD , Lamb LR , D’Alessandro HA . Mitigating the Impact of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Vaccinations on Patients Undergoing Breast Imaging Examinations: A Pragmatic Approach . AJR Am J Roentgenol 2021. ; 217 ( 3 ): 584 – 586 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]