Abstract

The National Medical Commission of India introduced the Competency Based Curriculum in Medical Education for undergraduate medical students in 2019 with a new module named Attitude, Ethics and Communication (AETCOM) across the country. There was a consensus for teaching medical ethics in an integrated way, suggesting dedicated hours in each phase of undergraduate training. The AETCOM module was prepared and circulated as a guide to acquire necessary competency in attitudinal, ethical and communication domains. This study was aimed to explore the perceptions of students and medical teachers and identify the challenges in teaching and learning process of the newly implemented AETCOM module. It was a mixed method designed study with structured questionnaires for students and teachers at various medical schools in India. Based on the quantitative data, in-depth interviews with medical teachers were undertaken. Challenges were perceived by both students and teachers. The students had a mixed perception, facing difficulties in passive learning with scarce resource materials. Challenges identified by teachers were a lack of knowledge and skills required for teaching bioethics, the logistics of managing large numbers of students in the stipulated time frame, interdisciplinary integration—both horizontal and vertical, and assessment program in terms competency-based education. The study draws the attention of all stakeholders for a revision and efforts for further improvement in the teaching and assessment process, and setting a standard model in medical education in India.

Keywords: Assessment, Bioethics, Curriculum, Teaching–learning process

Introduction

In recent decades, the medical profession has been criticized for perceived breaches of professionalism and ethics. Doctors and health professionals are confronted with many ethical dilemmas and challenges. It is, therefore, the need of the hour to prepare them to deal with these problems. In that context, there was increased interest in preserving, promoting, teaching, assessing and researching medical professionalism (Mueller 2009). Medical education started taking initiatives worldwide on the promotion of interpersonal skills, professional behaviours and attitudes (ten Cate and de Haes 2000; Kim 2019), along with an increased emphasis on the personal development of medical students, including self-awareness, personal growth and well-being (Novack et al. 1999).

The objectives of teaching medical ethics should be to enable students to develop the ability to identify underlying ethical problems in medical practice, consider the alternatives under the given circumstances, and make decisions based on acceptable moral concepts and also traditional practices. Over the last two decades, several studies have shown that a majority of medical students (64–84%) believe that ethical practices are critically important in the provision of the highest standards of medical care (AlMahmoud et al. 2017). Similar developments for including bioethics in undergraduate medical curriculum was also mentioned by Mattick and Bligh (2006). Such systematic and standard approach with an organized way of dealing with ethical issues was missing in the Indian Medical curriculum. In order to address the gaps, the National Medical Commission of India introduced the Competency Based Curriculum in Medical Education (CBME) for undergraduate medical students in 2019 with a new module named Attitude, Ethics and Communication (AETCOM) across the country (Medical Council of India 2018). The module was structured into competencies and incorporated in the curriculum design for the students of the first to final years in undergraduate curriculum. It emphasizes domains beyond medical knowledge and clinical skills, e.g. communication, professionalism and a focus on health systems (Supe 2019; Frank et al. 2010; Harden 2007).

Because of the multi-dimensional construct of assessing bioethics or professionalism, the question arises how much groundwork is done to assess the students with the current pattern of assessment system (Ben-David 2000). Looking into multiple reasons for teaching bioethics and its assessment in medical students, operational measurement has become a major concern for those who are involved in medical education.

Objectives

The study was aimed to identify the challenges in process of teaching–learning and assessment of the recently (2018–2019) introduced AETCOM module in the undergraduate medical curriculum, which is uniform for all medical colleges in India.

The specific objectives were:

Identifying perception and experience of the teachers and undergraduate medical students on bioethics curriculum and teaching

Identifying challenges in teaching and assessment

Method

Design

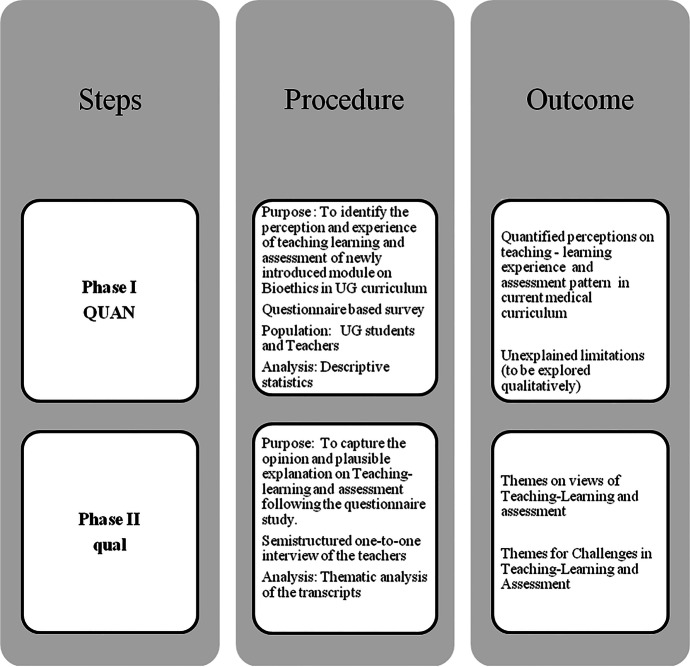

It was an explanatory study with a mixed methods design comprising (a) a quantitative phase I based on questionnaire study, and (b) a qualitative phase II, a descriptive study involving interviews semi-structured one-to-one interviews (Fig. 1). The data collection period was from October 2020 to August 2021. Institutional Ethics Committee approval from the institution of the first author was obtained in September 2020.

Fig. 1.

The visual diagram of the study design

Phase I: Study Population and Sample Size—Quantitative Part

It was with a purposive sampling, ensuring representation from different states of India in order to capture the heterogenicity in the teaching of bioethics across the country. Respondents were undergraduate medical students (357) from eight medical colleges of India, both from Government and private sectors, were included in the study through Coordinators of Medical Education Unit (MEU) of each college. They were the students who took admission in 2019 and were exposed to new CBME curriculum and AETCOM module for the first time in year 1. The number of medical teachers who responded were 47 from those colleges.

There were two separate questionnaires for the medical students and teachers, the links of the Google forms were sent to them separately. The questionnaire consisted of dichotomous, open and closed questions, Likert-type scale questions and multiple-choice questions. The questionnaires were validated, wherein Cronbach’s alpha for students’ questionnaire was 0.7493 (0.75 was considered to be accepted) and that of teachers was 0.76. The questionnaire for medical teachers was more detailed, containing four parts on the following: (1) opinion of teachers on curriculum, (2) perception on teaching–learning method of bioethics, (3) perception on assessment process of the subject and (4) challenges and limitations of teaching AETCOM.

Statistical analysis of the data was done using STATA 14.2.

Phase II: Qualitative Part

In order to capture the opinion and plausible explanation on different perception of the medical teachers of different phases from different medical colleges in India following the questionnaire study, the second phase of the research study (qualitative type) was planned. The sampling technique, used in this qualitative part, was also purposeful sampling. Eight faculty participants were identified for semi-structured interview from the questionnaire responses of phase I study. They were selected as per criteria based on availability, willingness to participate, ability to communicate experience and opinions in an articulated and reflective way and had training in medical education (Palinkas et al. 2015). They had different levels of hierarchy like Associate Professor, Professor and Head of the Department, and were from different specialities like Anatomy, Microbiology, Pharmacology, Medicine and Gynaecology, and various affiliations of university.

A telephonic interview was conducted with each of them separately by the principal investigator (who underwent training on qualitative research methodology). Average duration of each interview was 38 min. The interviews were semi-structured, recorded with prior consent and were utilized for obtaining the evidence which were found to be rapid, also yielded high response rate. Descriptive thematic analysis was done. The logic, applied, was that of thematic analysis of the transcripts of the interviews, to explore rich narrative data manually. This was reviewed by one Public Health specialist having expertise on qualitative research to reduce subjective bias and to increase interpretive credibility (Strauss 1987; Strauss and Corbin 1990).

Three main categories were framed namely teaching–learning methodology, assessment and challenges. Once the categories were formed, three subcategories of teaching–learning, two subcategories of assessment and two subcategories on challenges were generated. The codes were identified and placed accordingly.

Results

Phase I: Quantitative Analysis

Part A: Students’ Perception Analysis

The number of students from 8 medical colleges who responded to the questionnaire were 357, who took admission in May 2019. As per their response, 84.3% have been exposed to formal teaching of bioethics, and 15.7% were not. The latter might be because of COVID-19 situation, the institutions did not start the module on time or the students fail to attend those sessions. The majority of the students expressed that bioethics is as essential as clinical subject in medical curriculum though a few of them find the teaching boring and nonessential. Figure 2 includes overall perception on importance of ethical issues in practice, bioethics teaching and assessment.

Fig. 2.

Students’ perception on bioethics as a subject

Perceptions of students on different teaching–learning methods are shown in Table 1. We found that the students preferred to have maximum case scenario-based teaching. Other teaching methods preferred by them were role play and audio-visual film-based teaching. Formative assessment was preferred to both formative and summative. Less number of students supported only summative assessment. Peer assessment was also preferred by the students.

Table 1.

Students’ perception on preference of bioethics teaching–learning method

| Questions/topics | Yes | No | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Case scenario as a study method | 179 | 50.1 | 178 | 49.9 |

| Debates | 17 | 4.8 | 340 | 95.2 |

| Student teacher interaction | 35 | 9.8 | 322 | 90.2 |

| Role play | 39 | 10.9 | 318 | 89.1 |

| Didactic lecture | 4 | 1.1 | 353 | 98.9 |

| Audio-visual (film) | 68 | 19.0 | 289 | 81.0 |

| Small group discussion | 16 | 4.5 | 341 | 95.5 |

| Assessment by peer group | 251 | 70.3 | 106 | 29.7 |

Part B: Perception of Medical Teachers on Teaching–Learning and Assessment of Bioethics

A total of 47 teachers responded to the questionnaire. According to questionnaire, it was found that there was no core group or unit of medical teachers dedicated for teaching AETCOM module in any medical college. We found only a few teachers taught this subject for undergraduate medical students as per directive of Medical Education Unit of the institution. Details of responses are mentioned in Table 2. The majority of the teachers agreed to emphasize on development of moral reasoning skill which should be one of the mainstays in teaching bioethics.

Table 2.

Teachers’ perception on teaching–learning of bioethics as a subject (n = 47)

| Questions/topics | Yes | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Any course or training on bioethics | 24 | 51.1 |

| Whether teach bioethics or not | 14 | 29.8 |

| Whether any full-time teacher for bioethics teaching in med school | 20 | 42.6 |

| Whether students should know history of bioethics | 42 | 89.4 |

| Do you like to take any topic beyond the prescribed curriculum? | 34 | 72.3 |

| Whether assessment is necessary | 39 | 83.0 |

| Whether assessment guides the learning process | 18 | 38.3 |

| Whether assessment meets the desired outcomes of teaching–learning bioethics | 11 | 23.4 |

| Whether can provide professional self-regulation | 16 | 34.0 |

| Do you think students be assessed by personnel like patients, non-teaching staffs and peers? | 35 | 74.5 |

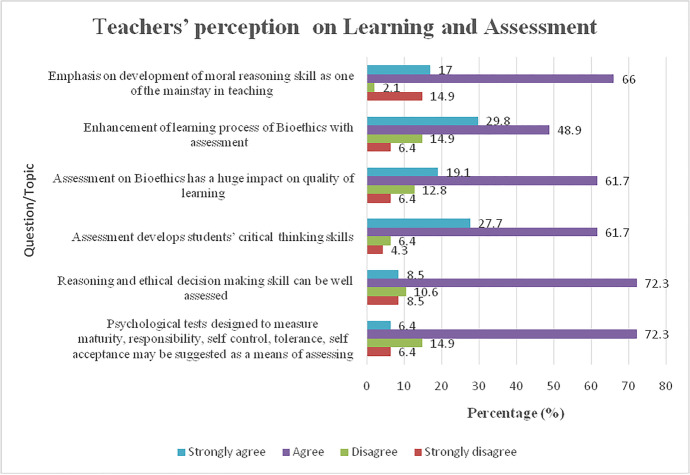

There was a split opinion on assessment of the subject. They also agreed on the facts that assessment develops student’s learning and critical thinking as well. It has a huge impact on the quality of learning. Reasoning and decision-making skill could be well assessed—was agreed upon by many the teachers (Fig. 3). At the same time, many of them opined that the assessment did not meet the desired outcome of teaching–learning bioethics in terms of Miller’s Pyramid. Therefore, they suggested the following types of assessment which could be introduced:

Formative based on their participation in session

Summative assessment by giving questions on various topics like principles of bioethics, rights of doctors and patient

Direct observation: debate/discussion with peers

Coding method, thematic comparison, compare reports

Personal moral development: sort the photocopies of all home work

Direct observation of workplace assessment in clinics, mentoring

Maintenance of log book

Communication exercises like role play, reflective writing, portfolios

360 degree feedback

Structured viva, Mini CEX

Fig. 3.

Teachers’ perception on learning and assessment

Part C: Comparison of Students’ and Teachers’ Perception on Specific Areas

We took five pertinent issues on teaching and assessment for comparing the perceptions of students and teachers. They are as follows:

Subject: Need for bioethics course: while about 11% students perceived that such course is not necessary for their practice as a clinician, significantly more students felt that bioethics course could help solve ethical dilemma as compared to teachers [students’ response vs teachers’ response: 331 (92.7%) vs 39 (83%), p = 0.02).

Method of teaching: most students and teachers favoured practical application-based learning. Students mainly favoured teacher-guided learning (193 (54%)), self-directed learning (44 (12.3%)) and project-based teaching learning (88 (24.6%)).

Teachers echoed similar feelings and mainly favoured brainstorming and debates illustrating ethical concerns (12 (25.5%)) and case-based teaching and debates (16 (34%)). Only one teacher favoured didactic way of teaching.

Assessment: whether assessment is necessary: students were bit hesitant about assessment of bioethics course. Less number of students perceived assessment necessary as compared to teachers albeit the difference was not statistically significant (70% vs 83%, p = 0.06).

Assessment by non-teaching personnel: both the students and teachers felt equally comfortable with assessment by non-teaching personnel (70.3% vs 74.5%, p = 0.55)

Type of assessment: there is significant difference in assessment choices between faculty and students. It appears that students are more inclined to formative assessment only whereas faculty is divided almost equally between the choices.

Phase II: Qualitative Analysis

Category 1: Teaching–Learning Methodology

Under this category, there were three subcategories namely (i) active learning, (ii) passive learning and (iii) curriculum. All the teachers who participated opined that there was a dire need of teaching and training on attitude, ethics and communication skill for the undergraduate medical students and they welcomed the implementation of new module of AETCOM in Indian Medical Curriculum.

Active Learning: The codes identified were case-based or problem-based teaching, role plays, village visits and bedside teaching. Respondents felt that there should be innovative way of teaching this subject unlike traditional teaching and that should be conducted in small groups. They identified that participatory learning has got a definite place here for better learning process, so more time should be allocated for this through case-based teaching, problem solving, debates, etc. In order to attain competency, the training can be started during the field visits and early clinical exposure of the students. The representative quotes are as follows:

-

(i)

“Essentially AETCOM module teaching should be in the form of small group teaching based on cases, problems and debates by allowing them to solve the dilemma”

-

(ii)

“Videos, narratives, role plays, again reflection writing, are must for actually reaching out to the ultimate aim of being at commoner real sense of teaching learning”

-

(iii)

“We have the opportunity of bedside teaching for the attitudinal aspects”; “Village visits are opportunities for the students to get trained in attitude and communication skill”

Passive Learning: The codes were mini-lecture, seminar, videos. According to them, didactic teaching in this area should be avoided as far as possible; it might not do justice to the topic and might not be made interesting to the students when it comes to attitudinal domain. Thus, they felt, “All should not be case scenario, all shouldn’t do role play, it will never work. It should be varied”, also “Seminars, videos can have impact on the students”.

Curriculum: The code identified was content. “Content of the module is minimal”, was the opinion of majority of the respondents. According to them, “Issues like equality, justice, non-discrimination, stigmatization, vulnerability are not addressed in the curriculum”. Moreover, they felt, “How to integrate with clinical subjects was not clear in the guidance booklet”.

Category 2: Assessment

Formative Assessment: All the respondents mentioned, “Assessment drives learning”, therefore, must be included. Interviews revealed that the medical teachers preferred formative assessment to summative assessment. Two of them felt that assessment was mostly done in English which sometimes became too technical and mechanical; many important views and opinions of the students get missed out during assessment because of language barrier, nervousness and hesitancy. Therefore, they suggested, “There should be a scope of assessment in vernacular language for assessing soft skills”. Assessment in vernacular language might give better idea of teaching–learning of soft skills and should be implemented in the process. According to them, peer assessment might be a welcome method as mentioned, “Is a good way to know students’ progress” but simultaneously, there remain chances of bias.

The most difficult part in assessment system was found to be that of manpower, i.e. teacher-student ratio which is not an ideal one both for teaching as well as assessment. Moreover, assessment of skill also was an area of concern by the teachers. They mentioned, “It is very difficult in Indian set up with a batch of more than 100 students and less man power” and “We can assess only knowledge part with huge number of students”. Another difficulty, that was pointed out, was in terms of time constraint in practical examination.

Summative Assessment: All the respondents mentioned, “It is necessary and help students for learning purpose”. Two of the respondents opined that there is very less scope of assessment of soft skill on this area, only the knowledge part can be assessed at the most and quoted as “It is not the appropriate or good method of assessment to assess soft skills” and “Not good for assessment of communication skill”.

Category 3: Overall Challenges

Teaching–Learning Process: The codes identified were faculty strength, expertise, infrastructure, content and resource materials and students’ interest.

All the Medical teachers, who participated, unanimously agreed with the challenging issues related to process of T/L, expertise, curricular content, time, manpower and the assessment process. Firstly, the teachers are not well trained in this area, they mentioned, “Most of the teachers are not aware of the subject”.

As mentioned previously, they opined that medical teacher-student ratio is much less than what is required for such training. There are challenges in managing with manpower and small group teaching covering the batch of 150 students. In this context, they felt, “More trained teachers are required” and “There is lack of time for the added area of teaching”.

More than one respondent opined that the students can understand the medical problem but often they are not be able to identify the ethical issues or problem and thereby how to address those. This calls for development of moral reasoning skill on ethical dilemma for the students, which is a challenging issue in current set up. In present setup, it was possible to assess only the knowledge part that is “Knows/K” of Millar’s pyramid (Carley 2015) if not the higher level. It might take some time for the faculty also to get skilled and equipped with skill station to assess the steps of solution and decision-making on ethical dilemma.

Another difficult area identified by the teachers was integration with other subjects. “Content of AETCOM module is minimal and they have suggested only a few issues, not enough and methods of the teaching–learning process. They have not suggested how to integrate the subject with others”. According to them, identifying the ethical principles and linking them with different subject and context was found to be tough and needed a thorough brainstorming and curricular revision. They felt that there was a need of training for the faculty member for further development of expertise for implementing the new module, which was not addressed in various basic course workshops for the teachers. There is lack of resource materials and textbooks. “Selecting resources from net may not be relevant in Indian context always”.

Respondents also commented on infrastructure of some of the medical colleges, as in many older colleges there is lack of set ups and space for small group teaching in newer ways.

Assessment: Respondents identified a few challenges on assessment. They felt that they were not well versed on assessment of soft skill. One of the teachers expressed that the prescribed assessment system could focus only assessment of lower cognitive domains of Bloom’s taxonomy (Ruhl 2021) such as remembering and understanding. There was very little scope to assess “Shows How” on Bioethics except for some limited and specific Communication skill in OSPE. They mentioned the following issues like “It is difficult to assess affective and psychomotor domain of teaching learning”, “May not be uniform”, “Students get nervous in OSCE stations, so proper assessment of communication skill is not done” and “OSPE stations are too much formal and away from real life”. Another limiting issue here was the time factor in assessment process for a batch of 150 to 250 students in respective colleges and proportionately the number of faculty members required for that.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the 2019 AETCOM module was the first structured formal module on Ethics, Professionalism and Communication skill, implemented in the Indian medical curriculum, along with competency-based medical education (CBME) (Medical Council of India 2018). The desired level of proficiencies for various competencies were mentioned in the booklet. The aim of this study was to explore the challenges faced after the implementation of the module. We found a mixed feeling amongst the students and teachers through their perceptions in different areas.

Teaching Professionalism and Bioethics includes development of critical thinking, and problem-solving abilities. Active learning techniques are the ones appropriate for such evolution (Heuer 2008), whereas didactic lecture on this subject was not welcomed by both students and teachers. Lecture has long been a standard way of teaching and concentrates primarily on conveying information in a one-way format. All teachers criticized lectures and agreed that case- or problem-based activities or debates could give students opportunities to discuss the issues, highlight conflicts and controversies on ethical problems and professional attributes, and enable them to share their viewpoint, addressing the issues of morality. Such teaching methods can give better learning opportunities on the development of critical thinking. It might not be possible to assess the same very formally, but definitely could help in students’ learning process. At the same time, it is important to note the limitations and challenges faced by the teachers in conducting such teaching. The teachers emphasized the need of faculty development, behavioural change and curricular restructuring for a successful implementation.

Integration of the module with different subjects on the list of competencies was one of the recommendations for better understanding and for relevance of a topic. This was an area of serious concern for the faculty members who were not much trained in “how to” and “how much” to integrate with different subjects, and thereby assessment per se. It needs to be covered in training and workshops for the teachers, explaining the steps of Harden’s ladder of integration, trans-disciplinary, and interdisciplinary integration (Harden 2000; Ananthakrishnan 2018). It should be emphasized that the aim of integration is to facilitate learning and explain the relevance of a topic to future practice (Ananthakrishnan 2018).

We know that assessment is a fundamental component of both learning and teaching as it frames what students learn and for their certification (Norcini 2003). It refers to the processes employed to make judgments on the achievements of students over a course of study (Harlen 2005). In traditional teaching, softer skills of communication or professionalism or ethical dilemma were not emphasized in teaching or assessment. But, AETCOM has prompted not only to teach and incorporate in undergraduate medical education, but also towards assessment. There was a mixed reaction in our study, especially from the teachers, who were lacking the experience and expertise in this field. According to them, only knowledge could be assessed in the present setup, though Medical Educators from the UK opined in one of the studies that knowledge and skills are far easier to assess attitudes or professionalism (Epstein and Hundert 2002). Students as well as teachers preferred formative assessment in the study. They felt that although it was more time consuming and that it increased their workload, but they find it, reference to their performance, feedback and guidance on how to improve.

The teaching of bioethics and professionalism is difficult, and equally complex is the assessment process. The question arises whether the assessment of AETCOM carries predictive value for the practice of medicine by the student in the long term. If yes, prospective assessment of students’ performance would be required, comparing performance results with subsequent professional conduct which is the biggest challenge in the present system. In order to retain “internal morality” of the medical profession with a meaningful commitment to uphold the standards of care, further academic rigor will be required to be applied to teaching, assessment and ongoing promotion of the ethical and professional conduct of medical students (Parker 2000).

Limitations of the Study

This study has certain limitations. The questionnaire study was conducted because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which restricted the movement of the investigator from personal contacts and interview. We received less teachers’ responses. The sample for qualitative study was drawn from former respondents based on questionnaire-based survey. Interviewees were only those who were available and agreed to talk over the telephone. Students were not included for interview.

In summary, the implementation of AETCOM in the new system of competency-based medical education is a welcome initiative by the Medical Council of India (then National Medical Commission). We find a mixed perception following implementation. The hidden curriculum of professional attributes, bioethics and communication skill has come into action in a structured format as a new subject. At the same time, certain teething issues are also no less boiling into definite challenges in different areas pertaining to teaching, learning, assessment and the overall curriculum. Since it is a multidisciplinary module, special attention is necessary to ensure the approach on integration of the topics both horizontally and vertically and thereby strengthening the relevance for future practice.

More Faculty Development Programs for teachers for all the subjects is necessary, especially to train in a different or innovative way of teaching and for the assessment of the AETCOM module. This draws the attention of all stakeholders to revision and further improvement for setting a standard model in medical education in India.

Acknowledgements

This study is a part of PhD thesis on Bioethics entitled, “Evaluation of Teaching Learning and Assessment of Bioethics for undergraduate medical students in Indian medical schools” of Dr Barna Ganguly enrolled in Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto (FMUP), Portugal. The authors would like to thank Mr Ajay Phatak, Statistician & Prof Amol Dongre, Department of Community Medicine, P.S. Medical College, Karamsad, Gujarat; Prof Luisa Castro, Department of Statistics, FMUP, Porto and Dr Ankit Patel, Department of Pharmacology, P.S. Medical College, Karamsad, Gujarat for technical help.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

Approved on 08 October 2020.

Consent for Participation

Informed consent process was incorporated in the Google questionnaire form. Only those who consented could access the questionnaire. For in-depth interview, separate informed consent process was on place.

Consent for Publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Dr Rui Nunes is the supervisor, and Dr Russell D’Souza is the Co-supervisor of Dr Barna Ganguly. The manuscript was reviewed and agreed for publication by both of them.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Al Mahmoud Tahra, Jawad Hashim M, Elzubeir Margaret Ann, Branicki Frank. Ethics teaching in a medical education environment: Preferences for diversity of learning and assessment methods. Medical Education Online. 2017;22(1):1328257. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2017.1328257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthakrishnan N. Competency based undergraduate curriculum for the indian medical graduate, the new MCI curricular document: positives and areas of concern. Journal of Basic, Clinical and Applied Health Science. 2018;1(1):34–42. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10082-01149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-David MF. The role of assessment in expanding professional horizons. Medical Teacher. 2000;22(5):472–477. doi: 10.1080/01421590050110731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carley, Simon. 2015. Educational theories you must know. Bloom’s Taxonomy. St. Emlyn’s. https://www.stemlynsblog.org/better-learning/educational-theories-you-must-know-st-emlyns/educational-theories-you-must-know-blooms-taxonomy-st-emlyns/. Accessed 8 Oct 2022.

- Epstein Ronald M, Hundert Edward M. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226–235. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank Jason R, Snell Linda S, ten Cate Olle, Holmboe Eric S, Carraccio Carol, Swing Susan R, Harris Peter, et al. Competency-based medical education: Theory to practice. Medical Teacher. 2010;32(8):638–645. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden Ronald M. The integration ladder: A tool for curriculum planning and evaluation. Medical Education. 2000;34(7):551–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden Ronald M. Outcome-based education: The future is today. Medical Teacher. 2007;29(7):625–629. doi: 10.1080/01421590701729930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlen Wynne. Teachers’ summative practices and assessment for learning- tensions and synergies. Curriculum Journal. 2005;16(2):207–223. doi: 10.1080/09585170500136093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer, Sarah. 2008. A case study method for teaching bioethics. MSc Thesis, Iowa State University.

- Kim, Daniel Takarabe. 2019. Henk ten Have: Global bioethics: An introduction. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 40: 63–66. 10.1007/s11017-018-9455-y.

- Mattick, K., and J. Bligh. 2006. Teaching and assessing medical ethics: Where are we now? Journal of Medical Ethics 32 (3): 181–185. 10.1136/jme.2005.014597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Medical Council of India. 2018. Attitude, Ethics and Communication (AETCOM) Competencies for the Indian Medical Graduate. https://www.nmc.org.in/information-desk/for-colleges/ug-curriculum/. Accessed 8 Oct 2022.

- Mueller Paul S. Incorporating professionalism into medical education: The Mayo Clinic experience. Keio Journal of Medicine. 2009;58(3):133–143. doi: 10.2302/kjm.58.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcini John J. Peer assessment of competence. Medical Education. 2003;37(6):539–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novack, D.H., R.M. Epstein, and R.H. Paulsen. 1999. Toward creating physician-healers: Fostering medical students’ self-awareness, personal growth, and well-being. Academic Medicine 74 (5): 516–520. 10.1097/00001888-199905000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Palinkas Lawrence A, Horwitz Sarah M, Green Carla A, Wisdom Jennifer P, Duan Naihua, Hoagwood Kimberly. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2015;42(5):533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker Malcolm H. Assessing medical students’ professional development and behaviour: A theoretical foundation. Focus on Health Professional Education. 2000;2(2):28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhl, Charlotte. 2021. Bloom’s taxonomy of learning. Simply Psychology, 24 May 2021. www.simplypsychology.org/blooms-taxonomy.html. Accessed 8 Oct 2022.

- Strauss AL. Qualitative analysis for social services. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Supe, Avinash. 2019. Graduate Medical Education Regulations 2019: Competency-driven contextual curriculum. National Medical Journal India 32 (5): 257–261. 10.4103/0970-258X.295962. [DOI] [PubMed]

- ten Cate, T.J., and J.C.J.M. de Haes. 2000. Summative assessment of medical students in the affective domain. Medical Teacher 22 (1): 40–43. 10.1080/01421590078805.