ABSTRACT

Background and Aims:

Pre-operative anxiety can affect psychological and physiological parameters during the intra-operative period. Pharmacological measures used to reduce pre-operative anxiety have their associated adverse effects. Pre-operative anaesthesia education is one of the non-pharmacological tools to reduce anxiety, but very limited literature is available in the Indian scenario. Hence, this study was designed to evaluate the effect of pre-operative counselling of patients using anaesthesia information sheet on pre-operative anxiety of patients who underwent elective surgery as the primary outcome. Secondary objectives were to assess the pre-operative anxiety for surgery, correlation of demographic data with pre-operative anxiety, and the common causes responsible for pre-operative anxiety.

Methods:

Total 110 patients were randomly allocated into two groups. Group-A was counselled using anaesthesia information sheet and in Group-B, conventional counselling was done during pre-anaesthesia check-up. Anxiety scores for anaesthesia and surgery were measured using visual analogue scale for anxiety (VAS-A). VAS-A score was compared pre- and post-intervention. Effect of intervention was assessed by comparing reduction in VAS-A score in both groups with paired t-test. Data were analysed using STATA (14.2) version.

Results:

The mean reduction in VAS-A for anaesthesia was more in Group-A compared to Group-B (16.6 ± 6.9 vs. 4.4 ± 5.8; P < 0.001). The mean reduction in VAS-A for surgery was more in Group- A compared to Group- B (14.6 ± 7.8 vs. 4.8 ± 7.3; P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Pre-operative counselling using anaesthesia information sheet is helpful in reducing pre-operative anxiety more efficiently. Further trials are required to assess transferability in other settings.

Key words: Anxiety, counselling, pre-operative period

INTRODUCTION

Anxiety is an emotional state characterised by feelings of nervousness, worry, apprehension, and tension due to high activity of the autonomic nervous system.[1,2] Earlier studies have reported the prevalence of pre-operative anxiety ranging from 10% to 80%.[3,4] Pre-operative anxiety has both psychological and physiological effects by activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis.[5] It can lead to deleterious effects on the haemodynamic parameters during the perioperative period; affect the overall anaesthesia management and surgical outcome by delayed awakening, post-operative pain, nausea–vomiting, delayed wound healing, and post-operative cardiac events.[4-6]

Pharmacological medications are used to reduce anxiety, but they may induce some adverse effects. In contrast to this, various non-pharmacological interventions like—reassurance, music therapy, breathing exercises, meditation, acupressure, pre-procedure education are used to allay pre-operative anxiety and they are inexpensive, easy to perform, do not require high level of technical skill or equipment and are without adverse effects.[7] Previous randomised controlled trials of pre-procedure education such as structured interview, multimedia, and question prompt tool were found to be more effective than conventional methods, but no study is available till date about the use of anaesthesia information sheet as a tool for pre-procedure counselling. No literature is available for the same in the Indian scenario. Hence, this study was designed to evaluate the effect of pre-operative counselling of patients using anaesthesia information sheet on anaesthesia-associated pre-operative anxiety as a primary objective. Secondary objectives were to assess pre-operative anxiety for surgery, correlation of demographic data with pre-operative anxiety and common causes of pre-operative anxiety.

METHODS

After obtaining institutional ethics committee approval (IEC/HMPCMCE/120/Faculty/19/215/20) and Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI/2021/04/032673) registration, this prospective randomised controlled study was conducted from April 2021 to December 2021. 110 patients of 18–70 years of age of either gender, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade I–III, minimum education up to the fifth grade, able to understand either Gujarati, Hindi, or English languages, posted for elective surgery of 1–3 hours duration from General surgery, Gynaecology, and Orthopaedic departments were included in our study. Patients with a previous diagnosis of mental illness, cognitive dysfunction or on anti-anxiety medications were excluded from the study. The principles of the declaration of Helsinki were followed during the conduct of the study.

Assuming a moderate effect size of 0.6, a sample size of 50 per group was required, allowing for 5% type-I error to achieve 85% power. Considering 10% loss to follow up for various reasons, the sample size was increased to 55 per group. Standard formula viz. n = 2 X [(Zα + Zβ) X σ/δ]2 was used to calculate the sample size and the calculations were performed in Microsoft Excel.

A total of 125 patients were assessed for eligibility and 110 patients were enroled. After obtaining written informed consent, patients were randomly allocated to intervention or control groups by computer-generated random numbers using WINPEPI (WINdows Programs for EPIdemiologists).[8] The allocation was kept in an opaque-sealed envelope and the envelope was opened only after an eligible participant consented for the study.

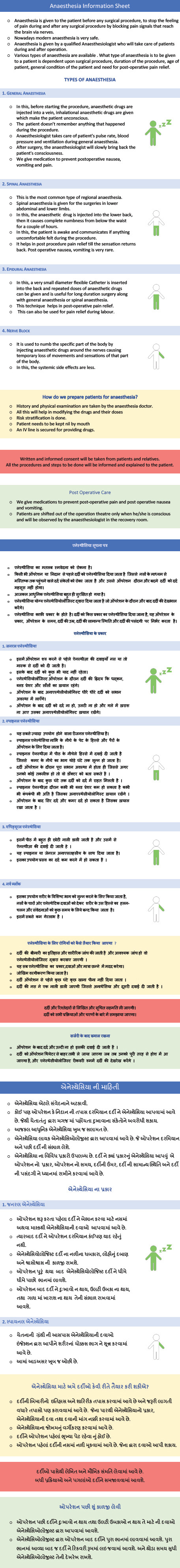

An anaesthesia information sheet was prepared in English, Hindi, and Gujarati languages with communicative translation method. Internal and external peer review was done to ensure face validity of the prepared information sheet. The sheet had details about the meaning of anaesthesia, different types of anaesthesia, pros and cons of each method, the preparation of patient for anaesthesia and post-operative care [Annexure 1].

During pre-anaesthesia check-up, on the day prior to the surgery, pre-operative anxiety was assessed by the principal investigator who was involved in the study, using two questionnaires of visual analogue scale of anxiety (VAS-A): (1) VAS-A for anaesthesia and (2) VAS-A for surgery. VAS-A question was rated from 0 to 100, in which 0 means no anxiety and 100 means maximum anxiety. The patients were asked about the possible causes of their anxiety, previous history of surgery, any negative experiences with previous surgeries etc. Participants in Group-A were counselled by a third-year resident involved in the study, using an anaesthesia information sheet. Their queries were clarified during the counselling. Participants in Group-B were given information about anaesthesia by conventional verbal counselling with addressing of their queries by the same third-year resident. After an interval of 2h, anxiety for anaesthesia and surgery was reassessed by the principal investigator in both the groups using VAS-A scale. This investigator was blinded for the type of counselling method. If VAS-A was more than 40 in any group, patients were advised to take an anti-anxiety drug in the form of tablet alprazolam 0.5 mg on the night before surgery.

Descriptive statistics [mean (standard deviation), frequency (%)] was used to depict the profile of the participants. Effect of both modalities on VAS-A for anaesthesia and VAS-A for surgery was assessed using paired t test. The reduction in VAS-A for anaesthesia and surgery was contrasted across the groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA) on difference scores. Variations in VAS-A for anaesthesia and surgery at baseline with various sociodemographic variables were assessed using ANOVA. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was performed in STATA (14.2) version.

RESULTS

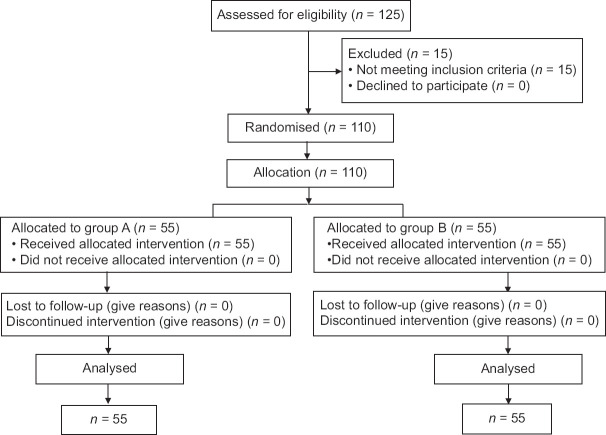

110 patients, (51 General surgery, 25 Gynaecology, and 34 Orthopaedics patients) were recruited in two groups (n = 55 each). All studied patients were analysed and followed up [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for the study participants

Demographic profiles (age, gender, marital status, literacy) along with previous history of surgery, any negative experience during previous surgery, types of anaesthesia, duration of surgery and type of surgery were comparable in both the groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the study population

| Variable | Details of Variable | Case (Group-A) (n=55) | Control (Group-B) (n=55) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46.18 (13.55) | 46.2 (14.71) | 0.99* | |

| Gender | Male | 56.4%(31) | 50.9%(28) | 0.57** |

| Female | 43.6%(24) | 49.1%(27) | ||

| Literacy | Primary | 20%(11) | 7.3%(4) | 0.06** |

| High school | 43.6%(24) | 63.6%(35) | ||

| Graduate & above | 36.4%(20) | 29.1%(16) | ||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 7.3%(4) | 9.1%(5) | >0.995*** |

| Married | 90.9%(50) | 90.9%(50) | ||

| Separated | 1.8%(1) | - | ||

| Previous surgeries | Yes | 36.4%(20) | 47.3%(26) | 0.25** |

| No | 63.6%(35) | 52.7%(29) | ||

| Negative experience during previous surgeries | Yes | 5.5%(3) | 3.6%(2) | >0.995*** |

| No | 94.5%(52) | 96.4%(53) | ||

| ASA grade | ASAgrade I | 3.6%(2) | 3.7%(2) | >0.995*** |

| ASAgrade II | 56.4%(31) | 61.8%(34) | ||

| ASA grade III | 40%(22) | 34.5%(19) | ||

| Type of anaesthesia | Regional | 70.9%(39) | 70.9%(39) | >0.995** |

| General | 29.1%(16) | 29.1%(16) | ||

| Type of surgery | General surgery | 43.6%(24) | 49.1%(27) | 0.84** |

| Gynaecology | 27.3%(15) | 23.6%(13) | ||

| Orthopaedics | 29.1%(16) | 27.3%(15) | ||

| Duration of surgery in hours | 1.91 (0.47) | 1.88 (0.55) | 0.76* |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; SD: Standard deviation. *Independent sample t-test **Chi square test. *** Fisher’s exact test. Data for Age and Duration of surgery in hours is presented as Mean (SD). Data for all other variables is presented as Percentage (number)

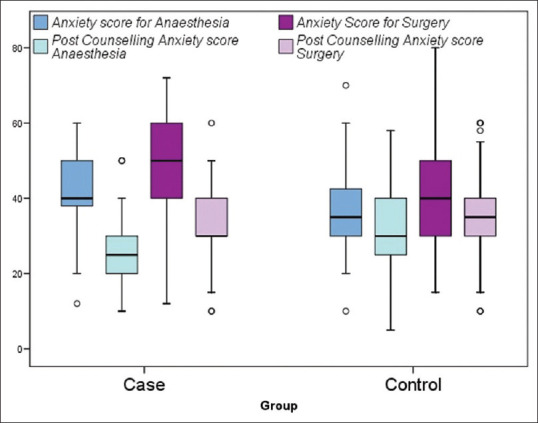

The overall incidence of pre-operative anxiety in the study population was 36.6%. Intra-group comparison of intervention Group-A and control Group-B for pre- and post-counselling scores for anxiety about anaesthesia and surgery was statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 2]. The reduction in mean of VAS-A for anaesthesia in Group-A was 16.6 ± 6.9 as compared to Group-B was 4.4 ± 5.8 (P < 0.001). Reduction in mean of VAS-A for surgery in Group-A was 14.6 ± 7.8, while in Group-B was 4.8 ± 7.3 (P < 0.001)[Figure 2, Table 2]

Table 2.

Comparison of Visual Analogue Scale of Anxiety (VAS-A) scores at different time points across the groups

| Parameter | Intervention Group-A n=55 | Control Group-B n=55 |

|---|---|---|

| VAS score of anxiety for Anaesthesia | ||

| Pre-counselling | 43.20 (11.17) | 36.85 (12.21) |

| Post-counselling | 26.57 (9.50) | 32.41 (11.57) |

| P-value for paired t-test | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Difference | 16.63 (6.92) | 4.44 (5.86) |

| P-value for ANOVA | <0.001 | |

| VAS score of anxiety for Surgery | ||

| Pre-counselling | 46.71 (12.89) | 39.73 (13.66) |

| Post-counselling | 32.07 (10.03) | 34.89 (12.60) |

| P-value for paired t-test | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Difference | 14.64 (7.81) | 4.84 (7.34) |

| P-value for ANOVA | <0.001 | |

VAS: Visual analogue scale; ANOVA: Analysis of variance; SD: Standard deviation. Data is presented as Mean (SD) for all parameters except P-value

Figure 2.

Pre- and post-counselling anxiety scores for anaesthesia and surgery amongst cases (Group-A) and control (Group-B)

Thematic analysis of the responses on the open-ended question “What are the things that you are afraid of?’’ The most common causes reported by patients were fear of intra-operative pain 87.3%, post-operative pain 41.8%, recovery issues 6.4%, and others 32.7%.

The female gender was significantly associated with higher pre-operative anxiety for anaesthesia (P < 0.001) and surgery (P = 0.01). Increasing ASA grade was associated with higher pre-operative anxiety for anaesthesia (P = 0.04) and surgery (P = 0.02) [Table 3]. About 21% of patients (n = 23) required anti-anxiety medications in the study population. Trends suggested lower need for anti-anxiety medications in intervention Group-A compared to control Group-B albeit the difference was not statistically significant [16.4% vs. 25.5%, P = 0.24]

Table 3.

Association of baseline pre-operative anxiety with demographic factors

| Variable | Details of Variable | VAS score of anxiety for anaesthesia | P | VAS score of anxiety for surgery | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.159 | 0.182 | |||

| Gender | Male | 36.6 (12.88) | <0.001 | 39.9 (13.99) | 0.01 |

| Female | 44 (9.74) | 46.9 (12.40) | |||

| Literacy | primary | 38.8 (11.21) | 0.20 | 44.3 (12.79) | 0.32 |

| High school | 41.8 (11.96) | 44.6 (13.33) | |||

| Graduate and above | 37.4 (12.38) | 40.3 (14.49) | |||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 32 (10.47) | 0.10 | 35.2 (10.97) | 0.18 |

| Married | 40.7 (12.04) | 43.9 (13.77) | |||

| Other | 35 | 40 | |||

| Previous surgeries | Yes | 41.9 (12.31) | 0.16 | 44.9 (14.79) | 0.25 |

| No | 38.6 (11.81) | 41.9 (12.77) | |||

| Negative experience during previous surgeries | Yes | 40 (18.25) | 0.84 | 40.4 (22.77) | 0.71 |

| No | 39.9 (11.98) | 43.2 (13.34) | |||

| ASA grade | ASA grade I | 31.2 (13.14) | 0.04 | 31.7 (14.10) | 0.02 |

| ASAgrade II | 38.3 (11.85) | 41.3 (12.63) | |||

| ASAgrade III | 43.3 (11.66) | 47.2 (14.22) | |||

| Type of anaesthesia | Regional | 38.6 (12.19) | 0.06 | 41.7 (13.56) | 0.09 |

| General | 43.4 (13.56) | 46.6 (13.51) | |||

| Type of Surgery | General Surgery | 39.96 (12.88) | 0.49 | 43.33 (14.58) | 0.34 |

| Gynaecology | 42.29 (11.89) | 46.16 (13.98) | |||

| Orthopaedics | 38.44 (11.02) | 40.88 (11.88) |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; VAS: Visual analogue scale; SD: Standard deviation. Data for all variables is presented as Mean (SD). Data for Age is presented as a number (Pearson’s correlation coefficient)

DISCUSSION

Patient anxiety was reduced after pre-operative counselling using either conventional verbal counselling or the newer method-anaesthesia information sheet. However, the use of anaesthesia information sheet for pre-operative counselling showed a significant reduction in anxiety. The overall incidence of pre-operative anxiety in our study was 36.6%, which is comparable to previous studies.[3,9,10]Bansal et al.[11] have highlighted in their narrative review that pre-operative anxiety is a neglected issue and it must be assessed routinely during pre-operative anaesthesia check-up and counselling should be done by anaesthesiologist in patients with a high level of anxiety.

There are various subjective and objective methods used to measure pre-operative anxiety. The objective methods can be more precise in measuring anxiety, but they require continuous monitoring, advanced equipment, skilled staff and are costlier. The subjective methods are easy to practise, do not require any specific instruments, do not require any technical skill and are not expensive. VAS is brief and simple to administer. It has a minimum respondent burden. These characteristics make it ideal for use in routine practice. VAS-A is a valid tool to measure anxiety.[12-15]

The most important finding of this study was a reduction in mean scores of VAS-A for anaesthesia and surgery which was significantly higher in the intervention group (Group-A) compared to control group (Group-B) (P < 0.001). In a prospective randomised controlled observational study, Jadin et al.[16] reported that VAS for pre-operative anxiety was found 1.2 points lower (out of 10) after structured interview as compared to standard interview in younger patients (<47 years). Jlala et al.[17] in a randomised controlled study, compared counselling by multimedia method versus conventional method, using VAS and State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and reported a reduction in pre-operative anxiety. They did not aim to separate anxiety related to anaesthesia and surgery in their methodology as contrast to the current study wherein we measured both separately. Lim et al.[18] used a question prompt list as a tool and STAI to measure anxiety in patients undergoing breast surgeries and reported a reduction in anxiety of the patients. Nevertheless, all the questions in the question prompt list were about surgery, whereas we used anaesthesia information sheet and evaluated anxiety for both anaesthesia and surgery. The findings of the current study were similar to previous studies[16–18] and confirm that anaesthesia information sheet is one of the methods of counselling that helps in reducing anxiety more effectively than conventional verbal methods. 16.4% patients were advised anti-anxiety medication in Group-A compared to 25.5% in Group-B, thereby suggesting the lower need for antianxiety medication in Group-A.

The female gender was significantly associated with higher pre-operative anxiety for anaesthesia and surgery in this study. This finding corroborates with previous studies demonstrating higher pre-operative anxiety amongst females as compared to males.[9,17,19] Unfamiliar environment, separation from family, fear of one’s life, length of hospital stay, post-operative pain were the points of concern for female patients.[20] Female patients may need additional comprehensive and individualised pre-operative education to reduce anxiety in the pre-operative period.[21] A systematic review and meta-analysis has shown satisfactory results with music therapy for female patients in the reduction of pre-operative anxiety.[22]

It was observed in this study that ASA physical status III patients had higher baseline pre-operative anxiety compared to ASA physical status I and II patients. This may be due to the fear that their comorbidities might increase the risk of surgery and anaesthesia. As per our knowledge, association of ASA physical status grading with pre-operative anxiety has not been studied in the past.

Other demographic variables were not found to be associated with pre-operative anxiety in the current study [Table 1]. Jafar et al.[10] reported increasing level of pre-operative anxiety with increasing level of education, whereas, Lim et al.[18] reported higher anxiety in patients with lower level of education. Mulugeta et al.[3] reported significant association between pre-operative anxiety and gender, age, marital status, educational status, residence, family size, pre-operative information and previous surgical experiences on bivariate analysis. Jadin et al.[16] reported no association of pre-operative anxiety with previous experience of anaesthesia, whereas, Jafar et al.[10] reported association of pre-operative anxiety with lack of previous surgical experience. This suggests that the variance in pre-operative anxiety varies based on cultural and contextual differences.

The participants in the current study were asked about the possible causes for their anxiety. The most common causes were fear for intra-operative pain (87.3%), post-operative pain (41.8%), recovery issues (6.4%) and others (32.7%) like recurrence of disease, back pain after spinal anaesthesia, sore throat, etc. Mulugeta et al.[3] in their study reported fear of complications (52.4%), concern about family (50.4%), fear of post-operative pain (50.1%) and fear of death (48.2%) as the common causes of pre-operative anxiety. Thus, causes for pre-operative anxiety are subjective and can vary depending upon the demographic profile of the patients, their culture, and regional conditions. Also, non-pharmacological pre-operative anxiety interventions should be contextually adapted based on these factors, because anxiety before surgery is a vexatious feeling associated with fear and illness.[4] The anaesthesia information sheet was designed on the basis of perspectives about anaesthesia that were prevalent in the general population. It was translated into Hindi and Gujarati languages as per vernacular language of the local subjects. So, it was an economical, reproducible, convenient, and effective non-pharmacological tool designed for this study to reduce pre-operative anxiety. It included a brief introduction to anaesthesia relevant to the layperson about the anaesthesiologist, types of anaesthesia, pre-anaesthetic check-up, consent, and intra-operative and post-operative management including pain control. The counselling process was not limited to the content of the sheet and patients were encouraged to seek clarifications.

This study has some limitations. Though several subjective and objective tools are available to measure the pre-operative anxiety, VAS-A was used. The results obtained by this study can show some subjective variations. Using multiple tools could have increased the accuracy of the results. Information related to anaesthesia was provided using an anaesthesia information sheet during pre-operative counselling, but similar information about surgery was not included as it was not a part of the study. Anxiety was assessed a day before surgery, before and after counselling using anaesthesia information sheet. Reassessing the patient in the pre-operative room, just before shifting the patient to the operation theatre would have given more information about the effectiveness of using anaesthesia information sheet. There was no pre-operative assessment by a psychiatrist to exclude the patients who had undiagnosed psychological and cognitive disorders coming to the hospital for the first time. It should be noted that pre-operative anxiety is a complex multifactorial phenomenon. Use of an information sheet during pre-operative counselling is just one method to reduce it. Determining various causes for pre-operative anxiety and developing multimodal strategies to reduce it should be tried with the intention of assessing synergistic interaction amongst different strategies. This can help to develop an institutional protocol to address the issue of pre-operative anxiety and management for the same.

CONCLUSION

Pre-operative counselling using anaesthesia information sheet is more effective in reducing pre-operative anxiety than conventional counselling in patients undergoing elective surgery. Females are more anxious than males and pre-operative anxiety increases with increase in ASA grading of the patients. The common factors leading to pre-operative anxiety amongst patients are fear of intra-operative and post-operative pain.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Ajay Phatak, M.Sc. MPH, DCA, Professor of Bio-Statistics, Adjunct Professor of Public Health, Charutar Arogya Mandal, Karamsad, Gujarat, India for helping with statistics.

ANNEXURE: ANNEXURE 1: ANAESTHESIA INFORMATION SHEET

REFERENCES

- 1.Baghele A, Dave N, Dias R, Shah H. Effect of preoperative education on anxiety in children undergoing day-care surgery. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63:565–70. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_37_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthias AT, Samarasekera DN. Preoperative anxiety in surgical patients—experience of a single unit. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2012;50:3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aat.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulugeta H, Ayana M, Sintayehu M, Dessie G, Zewdu T. Preoperative anxiety and associated factors among adult surgical patients in DebreMarkos and FelegeHiwot referral hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18:155. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0619-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopez-Yufera E, López-Jornet P, Toralla O, Pons-Fuster López E. Non-Pharmacological interventions for reducing anxiety in patients with potentially malignant oral disorders. J Clin Med. 2020;9:622. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sriramka B, Malik D, Singh J, Khetan M. Effect of hand holding and conversationalone or with midazolam premedication on preoperative anxiety in adult patients—A randomised controlled trial. Indian J Anaesth. 2021;65:128–32. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_705_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abate SM, Chekol YA, Basu B. Global prevalence and determinants of preoperative anxiety among surgical patients:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg Open. 2020;25:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijso.2020.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maranets I, Kain ZN. Preoperative anxiety and intraoperative anesthetic requirements. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1346–51. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199912000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramson JH. WINPEPI (PEPI-for-Windows): Computer programs for epidemiologists. Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2004;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-5573-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vadhanan P, Tripaty DK, Balakrishnan K. Pre-operative anxiety amongst patients in a tertiary care hospital in India—A prevalence study. J Soc Anesthesiol Nepal. 2017;4:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jafar MF, Khan FA. Frequency of preoperative anxiety in Pakistani surgical patients. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59:359–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bansal T, Joon A. Preoperative anxiety—an important but neglected issue:A narrative review. Indian Anaesth Forum. 2016;17:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Facco E, Stellini E, Bacci C, Manani G, Pavan C, Cavallin F, et al. Validation of visual analogue scale for anxiety (VAS-A) in pre anesthesia evaluation. Minerva Anestesiol. 2013;79:1389–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kindler CH, Harms C, Amsler F, Ihde-Scholl T, Scheidegger D. The visual analog scale allows effective measurement of preoperative anxiety and detection of patients’ anesthetic concerns. AnesthAnalg. 2000;90:706–12. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200003000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abend R, Dan O, Maoz K, Raz S, Bar-Haim Y. Reliability, validity and sensitivity of a computerized visual analog scale measuring state anxiety. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2014;45:447–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernandez PJ, Fuentes GD, Falcon AL, Rodriguez RA, Garcia PC, Roca CMJ. Visual analogue scale for anxiety and Amsterdam preoperative anxiety scale provide a simple and reliable measurement of preoperative anxiety in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2015;9:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jadin SMM, Langewitz W, Vogt DR, Urwyler A. Effect of structured pre anesthetic communication on preoperative patient anxiety. J Anesth Clin Res. 2017;8:767. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jlala HA, French JL, Foxall GL, Hardman JG, Bedforth NM. Effect of preoperative multimedia information on perioperative anxiety in patients undergoing procedures under regional anesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:369–74. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim L, Chow P, Wong CY, Chung A, Chan YH, Wong WK, et al. Doctor–patient communication, knowledge, and question prompt lists in reducing preoperative anxiety–A randomized control study. Asian J Surg. 2011;34:175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saini S, Dayal M. Preoperative anxiety in Indian surgical patients—Experience of a single unit. Indian J Appl Res. 2016;6:476–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masood Z, Haider J, Jawaid M, Alam SN. Preoperative anxiety in female patients:The issue needs to be addressed. Khyber Med Univ J. 2009;1:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng F, Peng T, Yang Q, Lui M, Chen G, Wang M. Preoperative communication with anesthetists via anesthesia service platform (ASP) helps alleviate patients'preoperative anxiety. Sci Rep. 2020;10:18708. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74697-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weingarten SJ, Levy AT, Berghella V. The effect of music on anxiety in women undergoing cesarean delivery:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3:100435. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]