Abstract

Two simple Bartonella bacilliformis immunoblot preparation methods were developed. Antigen was prepared by two different methods: sonication of whole organisms or glycine extraction. Both methods were then tested for sensitivity and specificity. Well-defined control sera were utilized in the development of these diagnostic immunoblots, and possible cross-reactions were thoroughly examined. Sera investigated for cross-reaction with these diagnostic antigens were drawn from patients with brucellosis, chlamydiosis, Q fever, and cat scratch disease, all of whom were from regions where bartonellosis is not endemic. While both immunoblots yielded reasonable sensitivity and high specificity, we recommend the use of the sonicated immunoblot, which has a higher sensitivity when used to detect acute disease and produces fewer cross-reactions. The sonicated immunoblot reported here is 94% sensitive to chronic bartonellosis and 70% sensitive to acute bartonellosis. In a healthy group, it is 100% specific. This immunoblot preparation requires a simple sonication protocol for the harvesting of B. bacilliformis antigens and is well suited for use in regions of endemicity.

Bartonella bacilliformis is a gram-negative, facultatively intracellular bacterium that is the causative agent of bartonellosis, a biphasic illness endemic in the high-altitude river valleys of Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador. The acute febrile phase, known as Oroya fever, is characterized by severe hemolytic anemia due to B. bacilliformis invasion of as many as 90% of erythrocytes. During and briefly following this febrile illness, a period of immunosuppression is associated with a high rate of secondary infections, most notably with Salmonella species (8). In the preantibiotic era, the acute phase of illness was thought to be fatal in about 40% of patients (29), although a mortality rate of 88% in untreated cases was observed during the 1987 Shumpillan outbreak (10). Appropriate antibiotic therapy reduces mortality to 8.8% (20). Four to 8 weeks after initial infection, the patient presents with the chronic phase of bartonellosis, dubbed verruga peruana. Vascular exophytic or nodular skin lesions, resulting from the invasion of vascular endothelial cells by the bacterium and a reactive angiogenic proliferation, characterize the verruga peruana. During the chronic phase of the illness, examination of peripheral-blood smears almost always fails to reveal B. bacilliformis (12), although in a small number of cases blood cultures may be positive (11).

Current methods employed for the diagnosis of bartonellosis have significant limitations. While performing a peripheral-blood smear by techniques such as Giemsa staining is rapid and simple, the sensitivity of peripheral-blood smear examination is very low in mild cases of disease and in the subclinical and chronic phases of illness. Diagnosis by blood culture is complicated by the need for prolonged incubation (1 to 6 weeks), which predisposes the system to contamination. Rates of blood culture contamination ranged from 7 to 20% in previously reported series (12, 13, 19). Histopathologic diagnosis with either hematoxylin and eosin or methionine silver stain is possible and is the current “gold standard” for the diagnosis of chronic bartonellosis. Even so, diagnosis by these staining methods is far from ideal. Frequently, the organisms are not clearly identifiable in the lesions and diagnosis relies on morphological changes, such as angioblastic proliferation with endothelial cell hyperplasia and engorgement, spindle cell proliferation, and histiocytic and lymphocytic invasion. These changes are pseudoneoplastic, and the possibility of incorrect classification of these lesions as cutaneous neoplasms or Kaposi's sarcoma by experienced pathologists has been clearly illustrated by Arias-Stella et al. (3).

In 1988, Knobloch (16) developed a B. bacilliformis-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay utilizing high-performance liquid chromatography and photodiode array detection for the purification of the B. bacilliformis antigen. However, the antigen preparation employed is laborious and requires technology that is expensive and is unavailable in regions where bartonellosis is endemic. The limitations of currently available diagnostic tests, recent outbreaks in areas of endemicity (7), the emergence of bartonellosis outside previously described zones of endemicity (1), and recent reports of atypical or subacute forms of bartonellosis (2) all indicate the need for new, improved diagnostic tests for this disease. Here we report an immunoblotting method useful in the diagnosis of both acute and chronic phases of bartonellosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sera.

Forty-two sera were collected from Peruvian patients with acute or chronic phases of bartonellosis. These included 18 patients from the Amazonas region and 24 patients from various regions of endemicity who had migrated to Lima and were treated at the Hospital Nacional Cayetano Heredia. Acute patients (n = 10) had documented positive peripheral-blood smears and were febrile at the time sera were taken. The remaining 32 sera were drawn from patients with chronic bartonellosis, defined as those patients who had a biopsy diagnosis of verruga peruana.

Control sera (n = 80) were taken from subjects from regions where bartonellosis was not endemic. These included 31 healthy adult laboratory workers in the Infectious Diseases Laboratory, Pathology Department, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (Lima, Peru), and 49 archived sera taken from a healthy pediatric population in Las Pampas de San Juan de Miraflores, a district of Lima. The median age of pediatric subjects was 2.1 years, with a range of 3 days to 17.7 years. Pediatric subjects generally were from Lima, while the adult control group spanned a wide range of economic and geographic origins.

Possible cross-reactions were thoroughly examined. Sera from patients infected either with bacteria highly homologous to B. bacilliformis (5, 6, 15, 22, 23) or with bacteria which have previously demonstrated cross-reactivity with B. bacilliformis surface antigens (17, 18) were collected. These included 12 sera from patients with cat scratch disease, provided by Specialty Laboratories, Inc. (Santa Monica, Calif.), as well as 20 archived sera from Peruvian patients with chlamydiosis. Richard Birtles, of the Unite des Rickettsies, Faculte de Medecine, Universite de la Mediterranee (Marseille, France), supplied us with 7 sera from patients with Q fever and 30 sera from patients with brucellosis. Twenty additional sera from patients with brucellosis were contributed by the National Institute of Health in Mexico, courtesy of Delores Correa. All sera examined for cross-reaction to these immunoblots were taken from patients native to regions where bartonellosis is not endemic.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

B. bacilliformis ATCC 510 was obtained from the United States Naval Medical Research Institute Detachment (NAMRID) in Peru. The bacteria were cultured in a biphasic medium. The solid component was a modified F1 medium (S. Romero, personal communication) containing 10% (vol/vol) defibrinated sheep's blood (Department of Public Health, School of Veterinary Medicine, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru), 1 g of glucose/liter, 20 g of tryptose (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.)/liter, 5 g of NaCl/liter, and 2% (wt/vol) agarose. The liquid phase contained RPMI medium (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) enriched with 5.9 g of HEPES buffer (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.)/liter, 2.0 g of Na2CO3/liter, and 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (Sigma). Specimens were incubated at 28°C for 7 to 14 days and then successively replicated in liquid media and incubated at 28°C for an additional 14 to 20 days as needed.

Antigen preparation.

Intact cells were isolated from the culture medium by centrifugation at 14,470 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed three times with Sorenson buffer (24) at 20,840 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Crude antigen was then harvested by one of two methods, either the sonication of whole organisms or glycine extraction (9). Briefly, in the first of these extraction methods, the pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, followed by three rounds of sonication (1 min) and chilling on ice (2 min). Insoluble particles were separated by centrifugation at 32,570 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The isolated supernatant was adjusted to pH 7.0 and used as an antigen. In the extraction of antigen by glycine, the washed pellet was agitated with an equal volume of 0.2 M glycine-HCl (pH 2.0) for 15 min at 25°C. Insoluble particles were separated by centrifugation at 32,570 × g for 30 min at 4°C, and the isolated supernatant was adjusted to pH 7.0. This solution was then dialized overnight at 4°C with molecular porous membranes (Spectrum Medical Industries, Los Angeles, Calif.) in a sterile distilled-water bath and used as an antigen. In both cases, resultant protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (4), and the antigen was stored at −70°C until it was needed.

SDS-PAGE.

Prepared antigen was incubated in a solution of 1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.1% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue, 40% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 0.01 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) (final protein concentration, 0.1 μg/μl) for 20 min at 65°C (26) under nonreducing conditions. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was then performed on 12% homogeneous gels. A modified discontinuous Tris-borate-sulfate-chloride buffer system was used, as previously described (14, 21, 26). Protein size was estimated by the use of low-range prestained protein molecular weight standards (GIBCO BRL), ranging from 2.3 to 43 kDa, and the LMW marker kit (Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Piscataway, N.J.), with markers ranging from 14.9 to 94 kDa. The gels were stained with silver nitrate (25).

Enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blotting.

Antigens separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred to nitrocellulose paper (0.2 μm pore size) in a blotting medium consisting of 212 mM Tris and 20% (vol/vol) methanol (pH 9.2) for 2 h at 1.4 mA (27). The blots were washed four times in 0.3% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (Sigma) in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.2) and twice with PBS alone. Cut strips were submerged in sera diluted 1:50 with 5.0% fat-free milk powder in PBS-Tween (28) and were agitated overnight. Unbound serum components were removed by five washes with warm (56°C) PBS-Tween, followed by five additional PBS-Tween washes with buffer at room temperature. The strips were then incubated for 1 h with 1:2,000 horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antibody to human immunoglobulin G (IgG) in PBS-Tween. Unbound conjugate was eliminated by three successive PBS-Tween washes and five washes with PBS alone. B. bacilliformis-specific antibodies were visualized with 0.14 M 3,3 diaminobenzidine for 10 min, and the reaction was quenched with distilled water (26).

Identification of diagnostic bands.

To identify diagnostic bands, SDS-PAGE results obtained from prepared antigen were compared to those obtained from a series of serum pools. Potential diagnostic bands were identified by a comparison of prepared antigen with both a serum pool taken from blood smear- or biopsy-confirmed cases of bartonellosis (positive control) and a second pool of normal sera taken from healthy North American subjects, which was acquired from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (negative control). In the final designation of diagnostic bands, consideration was given to the reactivity of these possible B. bacilliformis-specific antigens with sera taken from patients infected with Chlamydia psittaci, Bartonella henselae, Coxiella burnetii, and Brucella species, as well as with samples taken from healthy Peruvian controls, as described above. Antigenic bands yielding the greatest sensitivity and specificity, while producing the fewest cross-reactions in the sera examined here, were designated the diagnostic protein bands. The presence of at least one selected diagnostic antigen band was interpreted as a positive result.

Definitions.

For the purposes of this study, “specificity” was calculated from sera taken from a healthy group of negative controls. Cross-reacting sera were not included in the calculation of assay specificity, because brucellosis, Q fever, and chlamydiosis, although occurring, are not common diseases in populations affected by bartonellosis.

“Cross-reaction” values were calculated from the number of false-positive results in individuals with a specific disease. Cross-reacting sera were taken into account only within the scope of cross-reaction, not in the calculation of general specificity.

RESULTS

Diagnostic protein bands.

Antigen prepared by sonication revealed 34 bands, of which 7 were identified as possible diagnostic bands. These ranged from 13 to 42 kDa. The preparation of antigen by glycine extraction revealed 35 bands, of which 13 were identified as possible diagnostic bands. These had relative molecular masses ranging from 10 to 42 kDa.

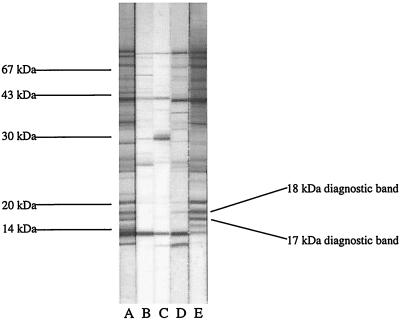

In each preparation method, two diagnostic bands were selected on the basis of high sensitivity and specificity (data not shown). Sonicated antigens produced diagnostic bands at 17 and 18 kDa (Fig. 1). In antigen prepared by glycine extraction, diagnostic bands corresponded to those at 16 and 18 kDa. Diagnosis based on the presence of at least one of the two selected diagnostic antigen bands permitted greater assay sensitivity without compromising specificity (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Diagnostic immunoblot for Carrion's disease prepared by sonication harvesting of B. bacilliformis antigen. Lanes: A, positive control pool; B, negative control pool; C, B. bacilliformis-negative serum; D, B. bacilliformis-positive serum taken from a patient with acute disease; E, B. bacilliformis-positive serum taken from a patient with chronic disease. The diagnostic bands used in immunoblot interpretation are shown.

Immunoblot sensitivity.

Both antigen preparation techniques produced immunoblots that were highly sensitive to the chronic phase of disease. One or both diagnostic bands were observed in 30 of the 32 sera (94%) taken from patients with confirmed cases of chronic bartonellosis when tested by either immunoblot preparation.

Sera taken from patients with Oroya fever produced less promising results. Although the sonicated immunoblot was reasonably sensitive to acute bartonellosis, the glycine extraction immunoblot displayed poor detection of B. bacilliformis infection in these sera. In patients suffering from acute disease, diagnostic bands were detected in 70% (7 of 10) of sera by the sonication immunoblot preparation and in 30% (3 of 10) of sera tested by the glycine immunoblot preparation. To determine whether the sensitivity discrepancy between acute and chronic bartonellosis was due to a lag in the formation of IgG antibody, a modified sonicated-antigen enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot was prepared, substituting horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antibody to human IgM in the conjugate binding step. This IgM-specific immunoblot failed to detect additional cases of acute bartonellosis, successfully identifying only 60% (6 of 10) of these cases (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Specificity and sensitivity results of bartonellosis diagnostic immunoblots prepared by either sonication or glycine extraction of B. bacilliformis antigen

| Method | Resultsa

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute disease

|

Chronic disease

|

Negative controls

|

|||||||

| + | − | Sensitivity (%) | + | − | Sensitivity (%) | + | − | Specificity (%)b | |

| Sonication | 7 | 3 | 70 | 30 | 2 | 94 | 0 | 80 | 100 |

| Glycine | 3 | 7 | 30 | 30 | 2 | 94 | 0 | 80 | 100 |

+, positive; −, negative.

Results reflect assay specificity in a healthy control group. Note that in patients identified with Q fever, brucellosis, and chlamydiosis, positive results occurred (Table 2).

Immunoblot specificity.

Both immunoblots were extremely specific (Table 1). All 31 sera taken from healthy laboratory personnel from regions where bartonellosis was not endemic were accurately interpreted as negative for B. bacilliformis infection when tested by either immunoblotting method. Furthermore, neither immunoblot preparation method produced false-positive readings in the 49 archived sera from pediatric subjects. In sum, both the sonication and glycine extraction methods were 100% specific in the healthy control group examined.

Cross-reactions with antigenically similar bacteria.

Infections with antigenically similar bacteria produced some cross-reactions with B. bacilliformis antigens (Table 2). The immunoblot produced by glycine antigen extraction yielded a greater frequency of antibody cross-reactions than did the sonicated immunoblot. In each immunoblot, Brucella species were particularly prone to cross-reactions. Sera from patients with brucellosis were read as B. bacilliformis positive in 34% (17 of 50) of sera tested via sonicated antigen preparation. Insufficient sera were drawn from two of these patients to permit their examination by glycine extraction immunoblotting. Of the remaining 48 brucellosis samples, 42% (n = 20) produced cross-reactions with glycine immunoblot antigens. In contrast, all 12 sera obtained from patients infected with B. henselae were nonreactive to B. bacilliformis antigen prepared by either method. Five percent (1 of 20) of the sera from patients infected by C. psittaci were read as positive when the sonication preparation was used. Again, insufficient sera were collected from six of these patients to allow their examination by the glycine extraction method. Of the 14 remaining sera, one (7%) was positive by the glycine extraction immunoblot preparation. Of the seven sera from Coxiella burnettii-infected patients, 14% (n = 1) were positive when tested with sonicated antigen while 29% (n = 2) tested positive in immunoblots performed with glycine-extracted antigen.

TABLE 2.

Antibody cross-reactions to diagnostic immunoblots for bartonellosis prepared by sonication or glycine extraction of B. bacilliformis antigen

| Method | Resultsa

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSD

|

Brucellosis

|

Q fever

|

Chlamydiosis

|

|||||||||||||

| + | − | CR (%) | Mexican sera

|

French sera

|

Total Brucella CR (%) | + | − | CR (%) | + | − | CR (%) | |||||

| + | − | CR (%) | + | − | CR (%) | |||||||||||

| Sonication | 0 | 12 | 0 | 8 | 22 | 27 | 9 | 11 | 45 | 34 | 1 | 6 | 14 | 1 | 19 | 5 |

| Glycine | 0 | 12 | 0 | 9 | 19 | 32 | 11 | 9 | 55 | 42 | 2 | 5 | 29 | 1 | 13 | 7 |

Results with the indicated potential cross-reacting antibodies. CSD, cat scratch disease; +, positive; −, negative; CR, cross-reaction.

DISCUSSION

The sonicated-immunoblot preparation method presented here is suited for use in regions of endemicity. This newly developed assay for bartonellosis diagnosis is both extremely specific and highly sensitive after the acute phase of disease. Importantly, the antigen preparation required is simple, cost effective, and easy to perform and uses equipment already available in most regions of endemicity. The diagnostic protein bands used were chosen after comparison with well-defined positive and negative serum control pools. Selected diagnostic antigens were located at 17 and 18 kDa in this sonicated-antigen preparation. The immunoblot prepared by glycine extraction is not suited for use in detecting acute cases of bartonellosis and gave higher rates of cross-reaction with antigenically similar bacteria. Consequently, we recommend only the sonicated immunoblot for use in detecting B. bacilliformis infection.

Whereas a previously described immunoblotting method (16) had sera from healthy Europeans as its only negative control, we used two different serum sets. Sera for the negative control pool used in selection of diagnostic bands were taken from healthy North Americans (a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention serum pool), while the specificities of these assays were determined through the testing of healthy persons from regions of Peru where bartonellosis is not endemic. Using sera from subjects native to a tropical country is important to the specificity testing of any bartonellosis immunoblotting method, due to the possibility of cross-reactions with antigens from other infectious diseases which plague such areas. Probed against these negative sera, the diagnostic immunoblot presented here demonstrated high specificity.

The sonicated immunoblot we describe here yields reasonable sensitivity and specificity results. This diagnostic immunoblot is 70% sensitive to acute cases of bartonellosis and 94% sensitive to chronic cases of the disease. An IgM-specific immunoblot was no more sensitive to acute bartonellosis than was an IgG immunoblot. The assay is extremely specific, with 100% specificity.

While previous published reports have not carefully examined the role of cross-reactions in diagnostic immunoblotting methods for bartonellosis, we thoroughly investigated possible antibody cross-reactions. Antibodies to several different bacteria were found to cross-react with the diagnostic B. bacilliformis antigens utilized in this immunoblotting technique. These cross-reactions result from the high degree of antigenic similarity between B. bacilliformis and the bacteria examined here (5, 6, 15, 17, 18, 22, 23). Antibodies to C. psittaci produced cross-reactions in 5% of the sera tested. Antibodies to C. burnettii produced cross-reactions in 14% of the sera. A high degree of cross-reactivity with antibodies to Brucella species was observed, as 34% of the sera examined yielded cross-reactions to the B. bacilliformis diagnostic antigens used. The high cross-reactivity of these immunoblots with sera taken from patients with brucellosis is disconcerting, but both bartonellosis and brucellosis are uncommon; we do not recommend the use of these assays in areas where brucellosis is highly endemic. Furthermore, although brucellosis is endemic to Peru, it is now becoming a relatively rare disease due to the institution of widespread pasteurization of dairy products. One benefit of particular interest is the lack of cross-reaction with antibodies to B. henselae. Despite the extensive homology between these species, no cross-reactions with B. henselae antibodies were found. The fidelity of this immunoblotting technique to B. bacilliformis, relative to B. henselae, is especially important given the clinical similarity of bartonellosis and bacillary angiomatosis.

In 1988, Knobloch (16) reported a B. bacilliformis-specific immunoblotting technique which involved a three-step antigen purification protocol requiring high-performance liquid chromatography and photodiode array detection. Although this immunoblot does yield high sensitivity and specificity, the costly, laborious techniques utilized in its preparation preclude its widespread implementation in laboratories in areas of endemicity. In this report, we present an immunoblotting protocol that is a simple, time- and cost-effective technique requiring no special technology. The ease of sonicated immunoblotting, the low sensitivity of peripheral-blood smear examination in nonacute forms of disease, and the difficulty of diagnosis by biopsy make this immunoblotting method especially useful for developing countries such as Peru. The sonicated immunoblot reported here is remarkably sensitive to B. bacilliformis antibodies that are present in the sera of patients with chronic disease while yielding reasonable results in acute disease. This sonicated-antigen immunoblot is ideally suited for use in regions of endemicity and may be implemented both in the diagnosis of bartonellosis and to better determine the epidemiology of this disease. Future investigations will be performed to ascertain whether cross-reactions may be reduced by using a purified OMP preparation rather than the crude antigen employed here. Cross-reactivity to brucellosis in high-risk populations is the major defect of the present immunoblotting technique, and further definition of proteins is required to enable us to define an assay which does not cross-react with Brucella species. Indeed, additional work in the development of a diagnostic immunoblot for bartonellosis should focus on the effort to avoid cross-reaction with antibodies to the bacteria included in this study, most notably with Brucella species, without sacrificing the high sensitivity and specificity of the sonicated immunoblot reported here.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by the Fogarty ITREID-NIH training grant and the anonymous RG-ER fund.

We appreciate the technical assistance of J. B. Phu and D. Sara, as well as that of P. P. Maguiña. The comments of C. Sterling and T. Schmitz are also greatly appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander B. A review of bartonellosis in Ecuador and Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52:354–359. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.52.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amano Y, Rumbea J, Knobloch J, Olson J, Kron M. Bartonellosis in Ecuador: serosurvey and current status of cutaneous verrucous disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:174–179. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arias-Stella J, Lieberman P H, Erlandson R A, Arias-Stella J., Jr Histology, immunohistochemistry, and ultrastructure of the verruga in Carrion's disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986;10:595–610. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198609000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner D J, O'Connor S P, Hollis D G, Weaver R E, Steigerwalt A G. Molecular characterization and proposal of a neotype strain for Bartonella bacilliformis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1299–1302. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.7.1299-1302.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner D J, O'Connor S P, Winkler H H, Steigerwalt A G. Proposals to unify the genera Bartonella and Rochalimaea, with descriptions of Bartonella quintana comb. nov., Bartonella vinsonii comb. nov., Bartonella henselae comb. nov., and Bartonella elizabethae comb. nov., and to remove the family Bartonellaceae from the order Rickettsiales. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:777–786. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-4-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper P, Guderian R, Orellana P, Sandoval C, Olalla H, Valdez M, Calvopiña M, Guevara A, Griffin G. An outbreak of bartonellosis in Zamora Chinchipe Province in Ecuador. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:544–546. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuadra C M. Salmonellosis complication in human bartonellosis. Tex Rep Biol Med. 1956;14:97–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodwin C S, Blincow E, Peterson G, Saderson C, Cheng W, Marshall B, Warren J R, McCulloch R. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Campylobacter pyloridis: correlation with presence of C. pyloridis in the gastric mucosa. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:488–494. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray G C, Johnson A A, Thornton S A, Smith W A, Knobloch J, Kelley P W, Escudero L O, Huayda M A, Wignall F S. An epidemic of Oroya fever in the Peruvian Andes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;42:215–221. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.42.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrer A. Carrion's disease. II. Presence of Bartonella bacilliformis in the peripheral blood of patients with the benign form. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1953;2:645–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrer A, Cornejo-Ubillús J, Lung J, Espejo L, Flores M. –1960. Estudios sobre la enfermedad de Carrión en el valle interandino del Mantaro. II. Incidencia de la infección bartonellósica en la población humana. Rev Med Exp. 1959;13:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrer A, Urteaga O. Observaciones sobre la verruga el departmento de Cajamarca. I. Hemocultivos. Rev Med Exp. 1943;2:348–353. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jovin T K, Dante M L, Chrambach A. Multiphasic buffer systems output. Federal Scientific and Technical Information. PB 196085-196091. U.S. Springfield, Va: Department of Commerce; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly T M, Padmalayam I, Baumstark B R. Use of the cell division protein FtsZ as a means of differentiating among Bartonella species. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:766–772. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.6.766-772.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knobloch J. Analysis and preparation of Bartonella bacilliformis antigens. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:173–178. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knobloch J, Bialek R, Müller G, Asmus P. Common surface epitope of Bartonella bacilliformis and Chlamydia psittaci. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:427–433. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.La Scola B, Raoult D. Serological cross-reactions between Bartonella quintana, Bartonella henselae, and Coxiella burnetii. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2270–2274. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2270-2274.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maguiña-Vargas C, Pérez E. La enfermedad de Carrión y Leishmaniasis andina en la region de Conchucos, Distrito de Chavin, San Marcos y Huantar, Provincia de Hauri, Departamento de Ancash. Diagnostico. 1985;16:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maguiña-Vargas C, Lumbreras H, Gotuzzo E, Crosby E, Irrivaren J. Clinical and laboratory study of patients with acute phase of Carrión's disease in the Hospital Base Cayetano Heredia between 1969–1987. Publication 63. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: International Congress for Infectious Diseases; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neville D M, Jr, Glossmann H. Molecular weight determination of membrane protein and glycoprotein subunits by discontinuous gel electrophoresis in dodecyl sulfate. Methods Enzymol. 1974;32B:92–102. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(74)32012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Connor S P, Dorsch M, Steigerwalt A G, Brenner D J, Stackebrandt E. 16S rRNA sequences of Bartonella bacilliformis and cat scratch disease bacillus reveal phylogenetic relationships with the alpha-2 subgroup of the class Proteobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2144–2150. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2144-2150.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Padmalayam I, Anderson B, Kron M, Kelly T, Baumstark B. The 75-kilodalton antigen of Bartonella bacilliformis is a structural homolog of the cell division protein FtsZ. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4545–4552. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4545-4552.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorenson R L, Sasek C A, Elde R P. Phe-met-arg-phe-amide (FMRF-NH2) inhibits insulin and somatostatin secretion and anti-FMRF-NH2 sera detects pancreatic polypeptide cells in the rat islet. Peptides. 1984;5:777–782. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(84)90021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai C M, Frasch C E. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsang V C W, Peralta J M, Simons A R. Enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot techniques (EITB) for studying the specificities of antigens and antibodies separated by gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 1983;92:377–391. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)92032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsang V C W, Bers G E, Hancock K. Enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot (EITB) In: Ngo T T, Lenhoff H M, editors. Enzyme mediated immunoassay. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1985. pp. 389–414. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsang V C W, Hancock K, Wilson M, Parmer D F, Whaley S D, McDougal J S, Kennedy S. Enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot technique (western blot) for human T-lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus (HTLV-III/LAV) antibodies. Immunology series no. 15. Procedural guide. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinman D. Infectious anemias due to bartonella and related red cell parasites. Trans Am Philos Soc. 1944;33:243–287. [Google Scholar]