Abstract

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) is caused by obligate intracellular bacteria in the Ehrlichia phagocytophila group. The disease ranges from subclinical to fatal. We speculated that cell-mediated immunity would be important for recovery from and potentially in the clinical manifestations of HGE; thus, serum tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), gamma interferon (IFN-γ), IL-10, and IL-4 concentrations were studied. IFN-γ (1,035 ± 235 pg/ml [mean ± standard error of the mean]) and IL-10 (118 ± 46 pg/ml) concentrations were elevated in acute-phase sera versus convalescent sera and normal subjects (P ≤ 0.013 and P ≤ 0.018, respectively). TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-4 levels were not elevated. Cytokine levels in severely and mildly affected patients were not different. HGE leads to induction of IFN-γ-dominated cell-mediated immunity associated with clinical manifestations, recovery from infection, or both.

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) is a tick-borne zoonosis caused by an obligate intracellular Ehrlichia species similar or identical to Ehrlichia equi and Ehrlichia phagocytophila (1, 3). Most infections are mild; however, on occasion severe complications, including opportunistic infections and fatalities, have been documented (14). E. phagocytophila infection of sheep and goats and E. equi infection in horses may be complicated by opportunistic infections as well (15). Except for serologic studies, immunologic function in humans with HGE has not been previously studied. Most infections by obligate intracellular bacteria require intact cell-mediated immunity for recovery from and protection against reinfection (5). To further characterize the human immune response to HGE and to ascertain if cytokine expression is associated with disease severity, we tested sera from patients during acute illness compared with those of patients during convalescence for the presence of the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 1β (IL-1β), the TH1-associated immune cytokine gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and the TH2-associated cytokines IL-4 and IL-10.

(Presented in part at the Thirteenth Sesqui-Annual Meeting of the American Society for Rickettsiology, 21 to 24 September, 1997, Champion, Pa. [abstract no. 96].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

HGE was diagnosed from typical clinical manifestations plus (i) a single serum immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) titer of ≥160, (ii) a single serum IFA titer of ≥80 and morulae in peripheral blood neutrophils, (iii) seroconversion by IFA, (iv) culture recovery of the HGE agent, or (v) HGE agent DNA in acute-phase blood by PCR. Patients were considered severely affected if they were hospitalized.

Sera for cytokine and serologic analyses.

Acute-phase sera were obtained during active disease at the earliest interval after onset. Acute-phase sera, convalescent-phase sera obtained 10 or more days later, and sera from healthy adult subjects were stored frozen at −80°C.

IFA assay for HGE serodiagnosis.

A modified IFA assay was performed as previously described except with E. equi-infected equine neutrophils, E. equi-infected HL60 cells, or HGE agent Webster strain-infected HL60 cells (1). Sera reactive at a dilution of 1:80 were titrated.

Serum cytokine analysis.

Capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-4 were performed in duplicate with Endogen (Woburn, Mass.) capture ELISA. The sensitivities of the assays were as follows: IFN-γ, 15.63 pg/ml; IL-4, 6.25 pg/ml; IL-10, 4.7 pg/ml; TNF-α, 15.63 pg/ml; and IL-1β, 3.13 pg/ml.

Statistical analysis.

Analysis for variance of means between paired acute and convalescent samples was performed by paired, one-tailed Student's t tests or for other comparisons, unpaired, two-tailed, unequal-variance Student's t tests. Correlation analysis was used to establish the strength of associations between cytokine concentrations and day of illness.

RESULTS

Patient demographic, clinical, and diagnostic evaluations.

Fifteen patients with HGE were selected; nine had mild illness, and six had severe infections that required hospitalization (Table 1). Seven mildly affected patients and four severely affected patients came from the upper Midwest; the remaining two mildly and two severely ill patients came from southern New York State. Seven mildly ill patients and five severely ill patients had PCR evidence of HGE in their acute-phase blood. For PCR-negative patients, blood was obtained a median of 14 days after onset of illness versus 3.5 days in the PCR-positive group (P = 0.035).

TABLE 1.

Patient demographic, clinical, and diagnostic evaluations

| Patient | Locationa | Clinical course | Results

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute phase

|

Convalescent phase

|

|||||||

| Dayb | PCRc | IFAd | Day | PCRce | IFA | |||

| 1 | NY | Mild | 4 | + | <80 | 31 | ≥2,560 | |

| 2 | WI/MN | Mild | 3 | + | <80 | 30 | ≥2,560 | |

| 3 | WI/MN | Mild | 2 | + | <80 | 76 | 160 | |

| 4 | WI/MN | Mild | 21 | Neg | 320 | 224 | Neg | 5,120 |

| 5 | NY | Mild | 7 | + | <80 | 21 | 320 | |

| 6 | WI/MN | Mild | 7 | + | ≥2,560 | 31 | ≥2,560 | |

| 7 | WI/MN | Mild | 14 | Neg | 1280 | 72 | Neg | 20,480 |

| 8 | WI/MN | Mild | 3 | + | <80 | 40 | 320 | |

| 9 | WI/MN | Mild | 4 | + | <80 | 130 | Neg | 1,280 |

| 10 | WI/MN | Severe | 8 | + | ≥2,560 | 64 | ≥2,560 | |

| 11 | WI/MN | Severe | 2 | + | <80 | 31 | ≥2,560 | |

| 12 | WI/MN | Severe | 10 | Neg | <80f | 77 | Neg | 80 |

| 13 | NY | Severe | 3 | + | <80 | 22 | 640 | |

| 14 | WI/MN | Severe | 4 | + | <80 | 28 | Neg | 640 |

| 15 | NY | Severe | 1 | + | <80g | 10 | <80 | |

NY, New York; WI, Wisconsin; MN, Minnesota.

Day, day after onset of illness.

+, positive; Neg, negative.

IFA, IFA assay polyvalent antibody titer to E. equi or the HGE agent.

Blank, no sample tested.

Morulae identified in peripheral blood neutrophils.

HGE agent isolated in culture.

Of the acute-phase sera of 15 patients with HGE, 11 were seronegative and 4 had HGE agent antibodies (geometric mean titer [GMT], 1,280) (overall GMT, 101). The GMT was 254 (range, <80 to ≥2,560) in the PCR-positive patients and 80 (range, <80 to 2,560) in the PCR-negative patients. The patients with antibodies in acute-phase sera were infected for a longer interval than antibody-negative patients (11 days versus 3 days; P = 0.036) before testing. Convalescent or second sera were obtained a median of 31 days after the onset of illness (range, 10 to 224 days). Eleven patients demonstrated seroconversions, two had stable high titers, one had a twofold increase in antibody titer, one PCR- and culture-positive individual was seronegative in an assay of convalescent serum on day 10, and one seronegative patient with morulae in the blood during the acute phase had a convalescent titer of 80. The convalescent serum GMT was 926, and no significant difference was observed in the titers whether or not the patients were initially PCR positive (P = 0.18). Whole-blood samples from five patients which were tested by PCR during the convalescent phase were all negative (Table 1).

Cytokine results.

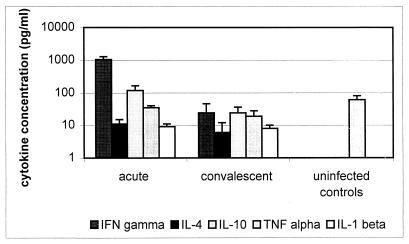

The results of cytokine ELISAs are shown in Fig. 1. Sufficient serum for all cytokine tests was available from two severely and three mildly affected patients and from six healthy subjects. An additional 4 severely and 6 mildly affected patients were tested for both IFN-γ and IL-1β, whereas an additional 10 healthy subjects were tested for TNF-α. IFN-γ concentrations were higher in acute-phase sera of HGE patients (1,035 ± 235 [mean ± standard error of the mean] pg/ml) than in convalescent sera (24 ± 22 pg/ml; P < 0.001) or normal controls (not detected; P < 0.013). No difference was observed between the IFN-γ concentrations in severely and mildly affected patients (P = 0.60). Similarly, serum concentrations of IL-10 were mildly elevated in patients during the acute phase of HGE (118 ± 46 pg/ml) compared with those during convalescence (24 ± 12; P < 0.004) and those in healthy controls (not detected; P < 0.019). Acute-phase serum IL-1β concentrations were also elevated (15 ± 2 pg/ml) compared with those of convalescent sera (8 ± 2 pg/ml; P < 0.034) and controls (not detected; P < 0.001), but the magnitude of these elevations was of questionable significance. No differences were found between IL-10 or IL-1β concentrations in mildly and severely affected patients with active HGE (P = 0.32 and 0.88, respectively). In general, low concentrations or no IL-4 or TNF-α were measured in most samples tested, and significant differences were not found between any groups except when acute-phase IL-4 levels were compared with those of healthy controls (P < 0.011). A decreasing IFN-γ concentration was associated with the postonset interval (r = −0.73), and patients without antibodies at presentation had higher levels of IFN-γ in the serum than did seropositive patients (1,359 ± 410 versus 145 ± 66 pg/ml; P < 0.001). IFN-γ levels in acute-phase serum were similar (P = 0.13) regardless of whether ehrlichial DNA was detected in the blood. Other cytokines were not detected more frequently in patients with antibodies or ehrlichia DNA present in acute-phase samples.

FIG. 1.

Serum cytokine concentrations (mean + standard error of the mean) in the acute (median, day 4 after onset) and convalescent (median, day 31 after onset) phases of HGE and in healthy adult control subjects.

DISCUSSION

Recovery and protection from infections by obligate intracellular bacteria often depend upon cell-mediated immune responses resulting in production of IFN-γ (5, 11). Here, evidence is presented that patients with HGE develop not only humoral immunity but also immune and proinflammatory cytokine responses. Despite the various intervals of collection of the sera tested, the height of some of these cytokine responses provides an estimation of the relative concentrations during acute phases of HGE.

HGE patients develop a mixed cytokine phenotype weighted toward a TH1 response. The magnitude of the IFN-γ response in humans is similar to that observed in other rickettsial infections in humans (11). However, there are insufficient data to link increased clinical severity with diminished TH1-type immunity. While the overall importance of IFN-γ in HGE is not established, models of vasculotropic rickettsial infections show that IFN-γ in concert with TNF-α induces a nitric oxide-dependent rickettsiacidal mechanism that is critical for survival and recovery (4). IFN-γ also effects Ehrlichia risticii and Ehrlichia chaffeensis destruction in macrophage cell lines by sequestration of arginine and depletion of intracellular iron stores, respectively (2, 12).

The source of these cytokines cannot be determined by the present studies. However, HGE agent infection of dimethyl sulfoxide-differentiated HL60 granulocytes induces chemokines but not proinflammatory or immune cytokines (8). Thus, infected cells are unlikely to be the primary source of IFN-γ or IL-10 in HGE. Since the HGE agent rarely infects differentiated macrophages (9), immune cytokines are probably generated after processing and presentation of ehrlichial antigens by macrophages to T lymphocytes.

Strong evidence that IFN-γ protects against infections by obligate intracellular bacteria is provided by in vitro and in vivo models, and IFN-γ may protect against HGE as well. However, protection has a consequence, as IFN-γ is potentially damaging to host cells (2, 4, 12). In HGE, tissue pathology and clinical illness are greater than ehrlichial burden predicts (3, 14). Moreover, IFN-γ secretion is associated with arthritis in Borrelia burgdorferi-infected C3H/HeJ mice, and high levels are detected in the sera of patients with infection-associated hemophagocytic syndrome, a finding observed in humans and in animal models of HGE (6, 7, 14). In contrast, the anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 may limit host-mediated tissue injury by down-regulating IFN-γ or other proinflammatory cytokines.

The presence of high acute-phase antibody titers in approximately 40% of HGE patients does not exclude an important role in recovery from infection or in immune-mediated disease (3). In vitro, antibody-E. chaffeensis complexes bind to Fc receptors of macrophages and elicit proinflammatory cytokine gene transcription and protein expression (10). However, the role of antibodies in cytokine-mediated inflammatory responses in vivo must be questioned, since the highest levels of IFN-γ were detected in patients prior to antibody responses, IFN-γ levels were negatively correlated with the interval after the onset of illness, and negligible quantities of TNF-α and IL-1β were detected. Passive transfusion of specific polyclonal antibody protects mice against challenge with the HGE agent (13). However, mice lack clinical signs of infection and immune reactions may not reflect those of infected humans (13). Our experiments with mice show a mixed TH response, with levels of IL-10 that may provide a degree of protection against the pathological effects of IFN-γ and other proinflammatory cytokines (11a).

High levels of IFN-γ and low levels of both IL-10 and IL-4 are produced with HGE, a phenotype most typical of a TH1 response, but no definite relationship between the presence or absence of cytokines and severity of illness has been demonstrated. Further studies will be required to confirm these findings and to elucidate the mechanisms of immunity for effective recovery from and protection against infection. Additional studies will be required to investigate whether immunopathologic processes are initiated and driven by the HGE agent or other E. phagocytophila group ehrlichiae that would suggest alternative strategies for the treatment and management of infected patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant R01 AI 41213-01 from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

We thank Kristin Asanovich and Jen Walls for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bakken J S, Dumler J S, Chen S M, Eckman M R, Van Etta L L, Walker D H. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in the upper midwest United States. A new species emerging? JAMA. 1994;272:212–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnewell R E, Rikihisa Y. Abrogation of gamma interferon-induced inhibition of Ehrlichia chaffeensis infection in human monocytes with iron transferrin. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4804–4810. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4804-4810.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dumler J S, Bakken J S. Human ehrlichioses. Newly recognized infections transmitted by ticks. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:201–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng H-M, Popov V, Walker D H. Depletion of gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha in mice with Rickettsia conorii-infected endothelium: impairment of rickettsiacidal nitric oxide production resulting in fatal, overwhelming rickettsial disease. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1952–1960. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1952-1960.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fresno M, Kopf M, Rivas L. Cytokines and infectious diseases. Immunol Today. 1997;18:56–58. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(96)30069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imashuku S, Ikushima S, Esumi N, Todo S, Saito M. Serum levels of interferon-gamma, cytotoxic factor, and soluble interleukin-2 receptor in childhood hemophagocytic syndromes. Leuk Lymphoma. 1990;3:287–292. doi: 10.3109/10428199109107916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keane-Myers A, Nickell S P. Role of IL-4 and IFNγ in modulation of immunity to Borrelia burgdorferi in mice. J Immunol. 1995;155:2020–2028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein M B, Hu S, Chao C C, Goodman J L. The agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) induces the production of myelosuppressing chemokines. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:427. doi: 10.1086/315641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein M B, Miller J S, Nelson C M, Goodman J L. Primary bone marrow progenitors of both granulocytic and monocytic lineages are susceptible to infection with the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1405–1409. doi: 10.1086/517332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee E H, Rikihisa Y. Anti-Ehrlichia chaffeensis antibody complexed with E. chaffeensis induces potent proinflammatory cytokine mRNA expression in human monocytes through sustained reduction of IκB-α and activation of NF-κB. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2890–2897. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2890-2897.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mansueto S, Vitale G, Cillari E, Mocciaro C, Gambino G, Piccione E, Buscemi S, Rotondo G. High levels of interferon-γ in boutonneuse fever. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1637–1638. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.6.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Martin, M. E., J. E. Bunnell, and J. S. Dumler. Pathology, immunohistology, and cytokine responses in early phases of HGE in a murine model. J. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Park J, Rikihisa Y. l-Arginine-dependent killing of intracellular Ehrlichia risticii by macrophages treated with gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3504–3508. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3504-3508.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun W, Ijdo J W, Telford III S R, et al. Immunization against the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a murine model. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:3014–3018. doi: 10.1172/JCI119855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker D H, Dumler J S. Human monocytic and granulocytic ehrlichioses. Discovery and diagnosis of emerging tick-borne infections and the critical role of the pathologist. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:785–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woldehiwet Z, Scott G R. Tick-borne (pasture) fever. In: Woldehiwet Z, Ristic M, editors. Rickettsial and chlamydial diseases of domestic animals. Oxford, United Kingdom: Pergamon Press; 1993. pp. 233–254. [Google Scholar]