Abstract

Guidelines recommend attempting to re-initiate statins in patients who discontinue treatment. Prior experiences while taking a statin, including side effects, may reduce a person’s willingness to re-initiate treatment. We determined the percentage of adults who are willing to re-initiate statin therapy after treatment discontinuation. Factors associated with willingness to re-initiate a statin were also examined. A statin questionnaire was administered and study examination conducted among black and white US adults enrolled in the nationwide REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study between 2013 and 2017. Among participants who self-reported ever having taken a statin (n=7,216, mean age 72 years, 53% women, 34% black), 1,081 (15%) reported having discontinued treatment. Among those who discontinued treatment, statin side effects, perceived lack of need for a statin, and cost were reported by 66%, 31%, and 3% of participants, respectively. Overall, 37% of participants who had discontinued treatment were willing to re-initiate statin therapy. Participants who discontinued treatment due to cost (prevalence ratio (PR) 1.61; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01, 2.57) were more likely to report a willingness to re-initiate therapy. Participants with a low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol ≥130 mg/dL versus <100 mg/dL (PR 0.69; 95%CI 0.53, 0. 88) and who discontinued treatment due to side effects (PR 0.51; 95%CI 0.41, 0.64) were less likely to report willingness to re-initiate statin therapy. In conclusion, a substantial proportion of participants who discontinued statin therapy were willing to re-initiate treatment. Healthcare providers should discuss re-initiation of statin therapy with their patients who have discontinued treatment.

Keywords: Statin, re-initiation, willingness

Statins are widely prescribed for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1–3 Despite being well-tolerated by most individuals, many people discontinue statin treatment.4–6 Discontinuation due to muscle pain, memory problems, cost, and perceived lack of benefit from therapy has been reported.7,8 Prior studies have reported statin discontinuation to be associated with an increased risk for CVD events.9–12 Several guidelines and scientific statements recommend attempting to re-initiate patients on a statin after treatment discontinuation.1,13–15 Many patients remain on a statin long-term after re-initiation.16,17 Identifying factors associated with willingness to re-initiate a statin may allow personalized strategies for those reluctant to restart treatment. The purpose of this study was to determine the percentage of people reporting willingness to re-initiate statin therapy following discontinuation, and examine the association of reasons for discontinuation and side effects attributed to statins with willingness to re-initiate treatment in the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study, a bi-racial cohort of men and women.

Methods

The REGARDS study is a nationwide study that enrolled participants from across the continental US.18 The study oversampled black participants, and approximately half of the sample was recruited from the eight southern US states referred to as the “stroke belt/buckle” (North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana). Participants completed a telephone interview and an in-home study examination at baseline (January 2003-October 2007), and are contacted every 6 months to identify stroke and coronary heart disease events for subsequent adjudication. Between May 2013 and November 2016, 14,233 participants completed a second in-home examination and telephone interview. The current analysis included participants who completed the second study examination and a statin questionnaire administered on a single occasion during follow-up telephone interviews conducted between November 2015 and March 2017 (n=13,007). We restricted the current analysis to 7,216 participants who self-reported ever having taken a statin at the time of the statin questionnaire administration (Supplemental Figure 1). All components of the REGARDS study were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. All participants provided written informed consent upon enrollment and again before completing the second study examination.

Data for the current analysis were collected through the REGARDS second study examination and a telephone interview. The statin questionnaire was administered to participants a median of 1.5 years (25th – 75th percentiles: 1 to 2 years) after the second examination. Statin discontinuation was defined as self-reporting stopping treatment for > 2 weeks for any reason and not taking a statin at the time of the questionnaire administration. Participants were asked about 3 potential reasons for discontinuation: cost, perceived lack of need, and side effects. Participants could report multiple reasons for discontinuing statin therapy (Supplemental Figure 2). Those responding “no” or “not sure” to all 3 reasons were categorized as having an “unknown” reason for discontinuation. For participants reporting side effects, we asked what side effects were experienced: muscle pain, tenderness or weakness (hereafter referred to as statin-associated muscle symptoms [SAMS] for conciseness), memory problems, or having an abnormal blood test for the liver or muscles. Participants could report multiple side effects and those responding “no” or “not sure” to experiencing all 3 side effects were categorized as having experienced “unknown” side effects.

The primary outcome was self-reported willingness to re-initiate statin therapy. Participants who discontinued their statin were asked “Would you be willing to restart a statin?” Participants who responded “no” or “not sure” were additionally asked “Would you be willing to restart a statin at a lower dose or less frequently than every day?” Participants responding “yes” to either question were categorized as being willing to re-initiate therapy.

Socio-demographic factors, current cigarette smoking, comorbidities, medication use and adherence, stress, depressive symptoms and physical and mental function were collected during a telephone interview coinciding with the second examination. Medical records were adjudicated by trained abstracters to identify hospitalized CVD events between the first and second in-home examination. During the second in-home study visit, blood pressure was measured, blood samples were collected, and an electrocardiogram was performed following standardized protocols.18 Covariate definitions are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Characteristics of participants who had ever taken a statin were calculated overall and by statin discontinuation status, using chi-square tests to determine the statistical significance of differences. We calculated frequencies of reported reasons for statin discontinuation. Next, the percentage of participants willing to re-initiate statin therapy was calculated, overall, and by participant characteristics and reasons for discontinuation. Participant characteristics included age, sex, race, region of residence, education, smoking status, perceived stress, depressive symptoms, physical and mental function, medication adherence, high blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, diabetes, history of CVD, and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C). Poisson regression with robust variance estimators was used to calculate prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for willingness to re-initiate statin therapy associated with participant characteristics and reason for discontinuation. The first model included adjustment for age, sex, and race. The second model included all participant characteristics and reasons for discontinuation simultaneously.

Next, we restricted the analysis to participants who discontinued statin use due to side effects. Frequencies of reported side effects were calculated. We calculated the percentage of participants who were willing to re-initiate statin therapy, overall, by participant characteristics and side effect experienced. We calculated the PR for willingness to re-initiate statin therapy using Poisson regression as described previously. Missing data were imputed using fully conditional specification and 10 data sets.19 Two sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Among 7,216 participants who reported ever taking a statin, the mean age was 74 years, 34% were black and 53% were women (Table 1). Overall, 1,081 (15%) participants had discontinued statin treatment. Participants who discontinued statin therapy were younger, more likely to be women, have low medication adherence, and have higher LDL-C compared with participants who had not discontinued treatment. Participants who discontinued therapy were less likely to have a high school education, to be taking antihypertensive medication, have diabetes or a history of CVD.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants who reported ever taking a statin, overall, and by statin discontinuation status.

| Characteristics | Statin discontinuation |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=7,216) |

Yes (n=1,081) |

No (n=6,135) |

||

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| < 65 | 997 (14%) | 188 (17%) | 809 (13%) | <0.001 |

| 65 – 74 | 3,442 (48%) | 519 (48%) | 2,923 (48%) | |

| ≥ 75 | 2,777 (39%) | 374 (35%) | 2,403 (39%) | |

| Black | 2,463 (34%) | 355 (33%) | 2,108 (34%) | 0.33 |

| Woman | 3,840 (53%) | 672 (62%) | 3,168 (52%) | <0.001 |

| Residing in Stroke Belt/Buckle | 4,073 (56%) | 621 (58%) | 3,452 (56%) | 0.47 |

| Less than high school education | 491 (7%) | 54 (5%) | 437 (7%) | 0.01 |

| Current smoker* | 509 (7%) | 63 (6%) | 446 (7%) | 0.09 |

| High perceived stress* | 1,968 (28%) | 296 (27%) | 1,690 (28%) | 0.88 |

| Depressive symptoms* | 763 (11%) | 113 (11%) | 650 (11%) | 0.89 |

| SF-12 physical component score* | ||||

| < 40 | 2,093 (31%) | 357 (35%) | 1,736 (30%) | 0.01 |

| 40–50 | 1,894 (28%) | 266 (26%) | 1,628 (28%) | |

| > 50 | 2,836 (41%) | 409 (39%) | 2,427 (42%) | |

| SF-12 mental component score* | ||||

| < 50 | 1,060 (15%) | 167 (16%) | 893 (15%) | 0.61 |

| 50–60 | 4.078 (60%) | 600 (58%) | 3,478 (60%) | |

| > 60 | 1,685 (25%) | 265 (26%) | 1,420 (25%) | |

| Low medication adherence* | 2,135 (32%) | 346 (35%) | 1,789 (31%) | 0.04 |

| High blood pressure** | 1,017 (14%) | 165 (15%) | 852 (14%) | 0.23 |

| Antihypertensive medication use* | 3,874 (54%) | 510 (47%) | 3,364 (55%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus* | 2,165 (31%) | 242 (22%) | 1,923 (32%) | <0.001 |

| History of CVD* | 2,214 (32%) | 261 (25%) | 1,953 (33%) | <0.001 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL)* | ||||

| < 100 | 4,267 (62%) | 278 (27%) | 3,989 (69%) | <0.001 |

| 100 – 129 | 1,491 (22%) | 306 (30%) | 1,185 (20%) | |

| ≥ 130 | 1,076 (16%) | 432 (43%) | 644 (11%) | |

Abbreviations –CVD, cardiovascular disease; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; SF-12, 12-item short form survey.

missing data for some participants

High blood pressure defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg.

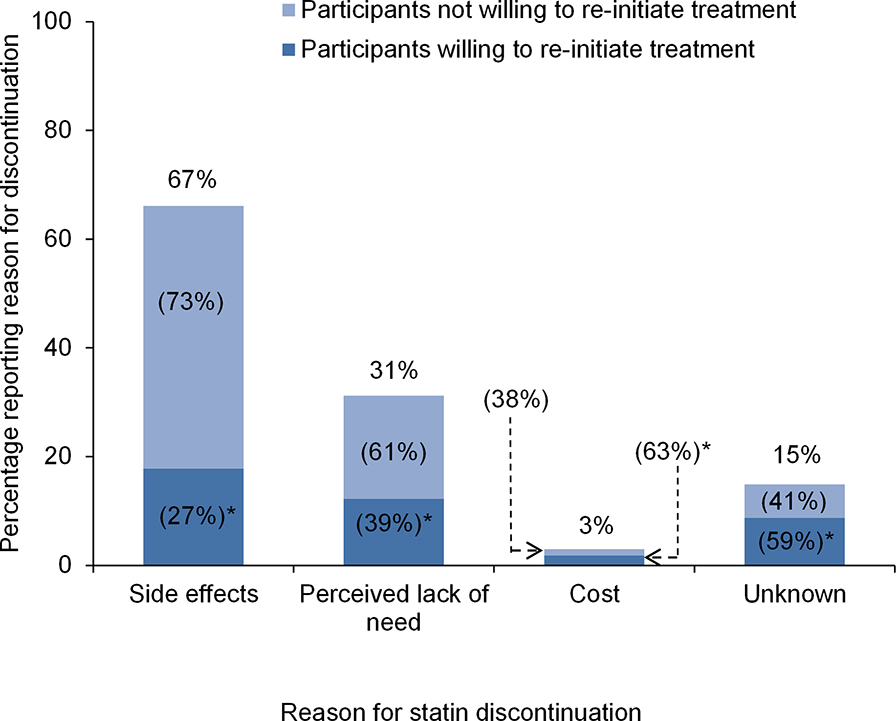

Among participants who discontinued statin use, 66% reported discontinuing due to side effects, 31% due to perceived lack of need, 3% reported discontinuing due to cost, and 15% for unknown reasons (Figure 1). Overall, 37% of participants who discontinued statin therapy reported a willingness to re-initiate treatment. Additionally, 27% of participants who discontinued their statin due to side effects reported a willingness to re-initiate statin therapy, compared with 39%, 63%, and 59% of participants who discontinued their statin due to perceived lack of need, cost, and unknown reasons, respectively. The percentage of participants willing to re-initiate statin therapy across participant characteristics is presented in Supplemental Table 2, left column. After multivariable adjustment, participants living in the stroke belt/buckle versus other regions of the US, with a physical component score of >50 versus <40, and who discontinued statin use due to cost were more likely to report willingness to re-initiate treatment (Table 2). Participants with LDL-C ≥130 mg/dL versus LDL-C <100 mg/dL and those who discontinued their statin due to side effects were less likely to report a willingness to re-initiate therapy.

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants reporting each reason for statin discontinuation and percentage of participants willing to re-initiate treatment.

Percentages on the top of each column represent the proportion of participants who discontinued their statin due to side effects, perceived lack of need, cost, or unknown reasons. *Percentages within columns represent, among those who discontinued their statin for a particular reason, the proportion willing and not willing to be re-initiated on a statin. For example, 63% of participants who discontinued their statin due to cost were willing to re-initiate statin therapy.

Table 2.

Prevalence ratios for willingness to re-initiate a statin among participants who discontinued treatment.

| Prevalence ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Characteristics | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|

| ||

| Age (years) | ||

| < 65 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 65 – 74 | 0.92 (0.71, 1.20) | 1.04 (0.79, 1.36) |

| ≥ 75 | 0.83 (0.62, 1.10) | 0.94 (0.70, 1.26) |

| Black | 1.29 (1.05, 1.59) | 1.20 (0.97, 1.49) |

| Woman | 0.81 (0.66, 0.99) | 0.86 (0.69, 1.06) |

| Region of residence | ||

| Non-Belt/Buckle | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Stroke Belt/Buckle | 1.18 (0.96, 1.44) | 1.25 (1.01, 1.53) |

| Less than high school education | 0.99 (0.62, 1.57) | 0.95 (0.59, 1.53) |

| Current smoker | 1.39 (0.97, 1.99) | 1.43 (0.99, 2.06) |

| High perceived stress | 1.05 (0.85, 1.31) | 1.04 (0.81, 1.34) |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.05 (0.76, 1.44) | 0.94 (0.64, 1.38) |

| SF-12 physical component score | ||

| < 40 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 40–50 | 1.28 (0.98, 1.67) | 1.24 (0.94, 1.64) |

| > 50 | 1.35 (1.06, 1.71) | 1.33 (1.01, 1.76) |

| SF-12 mental component score | ||

| < 50 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 50–60 | 0.95 (0.73, 1.24) | 0.87 (0.63, 1.18) |

| > 60 | 0.76 (0.55, 1.04) | 0.73 (0.50, 1.05) |

| Low medication adherence | 0.87 (0.70, 1.08) | 0.86 (0.69, 1.07) |

| High blood pressure* | 0.93 (0.70, 1.23) | 0.88 (0.66, 1.17) |

| Antihypertensive medication use | 1.02 (0.83, 1.25) | 1.06 (0.86, 1.31) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.14 (0.91, 1.44) | 1.12 (0.88, 1.43) |

| History of CVD | 0.86 (0.67, 1.09) | 0.89 (0.69, 1.15) |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | ||

| < 100 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 100 – 129 | 0.78 (0.61, 1.00) | 0.85 (0.66, 1.09) |

| ≥ 130 | 0.61 (0.48, 0.78) | 0.69 (0.53, 0.88) |

| Reason for discontinuation** | ||

| Side effects | 0.50 (0.41, 0.62) | 0.51 (0.41, 0.64) |

| Lack of perceived need | 1.09 (0.89, 1.35) | 0.86 (0.68, 1.08) |

| Cost | 1.74 (1.10, 2.74) | 1.61 (1.01, 2.57) |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; CI, confidence interval; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; SF-12, 12-item short form survey.

Model 1 includes age, race, and sex

Model 2 includes all covariates listed in table

High blood pressure defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg.

Prevalence ratios calculated comparing the proportion of participants reporting versus not reporting individual reasons for discontinuation.

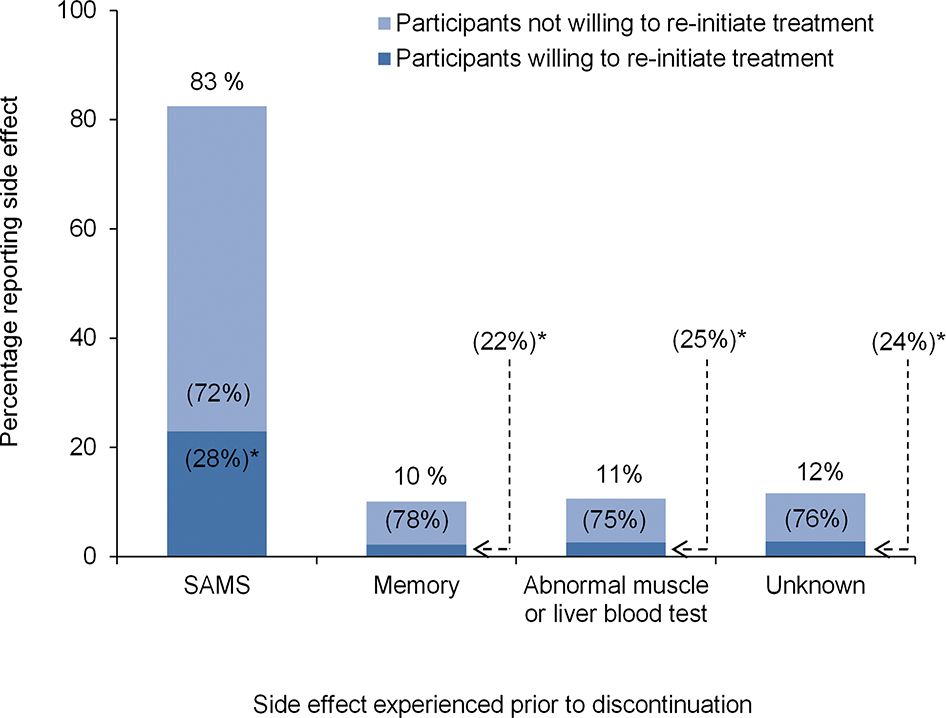

Among 715 participants who discontinued taking a statin due to side effects, 83% reported doing so due to SAMS, 10% due to memory problems, 11% due to an abnormal muscle or liver blood test, and 12% due to unknown side effects (Figure 2). In addition, 28% of participants who discontinued their statin due to SAMS reported a willingness to re-initiate statin therapy, compared with 23%, 25%, and 24% who discontinued due to memory problems, abnormal muscle or liver blood tests, and unknown side effects, respectively. Among participants who discontinued taking their statin due to side effects, the percentage willing to re-initiate therapy across participant characteristics is presented in Supplemental Table 2, right column. After multivariable adjustment, participants with LDL-C ≥130 mg/dL versus LDL-C <100 mg/dL were less likely to report a willingness to re-initiate a statin (Table 3). None of the individual side effects studied were associated with a willingness to re-initiate therapy.

Figure 2.

Percentage of participants reporting side effects prior to discontinuation and percentage of participants willing to re-initiate treatment.

Percentages on the top of each column represent the proportion of participants who reported discontinuation due to SAMS, memory problems, an abnormal liver or blood test, or unknown reasons among those who discontinued their statin due to side effects. *Percentages within columns represent the proportion of participants willing and not willing to be re-initiated on a statin among those reporting particular side effects. For example, 29% of participants who discontinued their statin due SAMS reported a willingness to re-initiate statin therapy.

Abbreviations: SAMS, statin-associated muscle symptoms

Table 3.

Prevalence ratios for willingness to re-initiate a statin among participants who discontinued treatment due to side effects.

| Prevalence ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Characteristics | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|

| ||

| Age (years) | ||

| < 65 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 65 – 74 | 1.05 (0.70, 1.57) | 1.10 (0.72, 1.66) |

| ≥ 75 | 0.91 (0.59, 1.42) | 0.97 (0.61, 1.53) |

| Black | 1.21 (0.89, 1.65) | 1.18 (0.85, 1.64) |

| Woman | 0.81 (0.60, 1.08) | 0.82 (0.60, 1.13) |

| Region of residence | ||

| Non-Belt/Buckle | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Stroke Belt/Buckle | 1.27 (0.94, 1.70) | 1.25 (0.93, 1.70) |

| Less than high school education | 0.95 (0.49, 1.87) | 0.91 (0.46, 1.79) |

| Current smoker | 1.48 (0.89, 2.48) | 1.48 (0.88, 2.49) |

| High perceived stress | 1.11 (0.82, 1.52) | 1.10 (0.78, 1.56) |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.01 (0.63, 1.61) | 0.83 (0.47, 1.45) |

| SF-12 physical component score | ||

| < 40 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 40–50 | 1.25 (0.86, 1.81) | 1.30 (0.88, 1.92) |

| > 50 | 1.28 (0.91, 1.80) | 1.45 (0.98, 2.13) |

| SF-12 mental component score | ||

| < 50 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 50–60 | 0.84 (0.59, 1.22) | 0.75 (0.48, 1.17) |

| > 60 | 0.69 (0.44, 1.07) | 0.68 (0.40, 1.15) |

| Low medication adherence | 0.83 (0.60, 1.13) | 0.87 (0.63, 1.19) |

| High blood pressure* | 1.03 (0.70, 1.52) | 0.98 (0.65, 1.46) |

| Antihypertensive medication use | 1.21 (0.90, 1.62) | 1.24 (0.91, 1.67) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.20 (0.86, 1.66) | 1.13 (0.80, 1.60) |

| History of CVD | 1.06 (0.77, 1.47) | 1.05 (0.75, 1.48) |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | ||

| < 100 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 100 – 129 | 0.74 (0.51, 1.07) | 0.75 (0.51, 1.09) |

| ≥ 130 | 0.63 (0.44, 0.89) | 0.63 (0.44, 0.91) |

| Side effects reported** | ||

| SAMS | 1.26 (0.85, 1.88) | 1.22 (0.81, 1.83) |

| Memory problems | 0.77 (0.46, 1.29) | 0.73 (0.43, 1.23) |

| Abnormal blood test | 0.90 (0.56, 1.44) | 0.91 (0.56, 1.47) |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; CI, confidence interval; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; SAMS, statin-associated muscle symptoms; SF-12, 12-item short form survey.

Model 1 includes age, race, and sex

Model 2 includes all covariates listed in table

High blood pressure defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg.

Prevalence ratios calculated comparing the proportion of participants reporting versus not reporting each side effect.

Discussion

In this population-based sample of black and white adults, 15% of participants who reported ever taking a statin discontinued treatment. The most frequently reported reason for statin discontinuation was side effects. Over one-third of participants who discontinued taking a statin reported a willingness to re-initiate therapy. Although discontinuation due to side effects was associated with a lower likelihood for willingness to re-initiate therapy, a substantial percentage of participants who discontinued their statin due to side effects expressed a willingness to re-initiate treatment.

Statins are effective in lowering LDL-C concentrations and reducing the risk of CVD events.1–3 Despite the risk reduction benefits of statins, a high percentage of people discontinue treatment,16 especially within 12 months of initiation.4,5,16 The percentage of participants who had discontinued taking statins was lower in the current analysis when compared to previous studies.11 Statin discontinuation was only assessed at one time point in the current study and we were not able to account for multiple periods of discontinuation and re-initiation. The variation in the rates of statin discontinuation across studies may reflect differences in the criteria used to define discontinuation.

Many guidelines recommend that healthcare providers attempt to re-initiate a statin after a patient discontinues treatment. The suggested course of re-initiation by the National Lipid Association includes using the same dose, dose-reduction, statin substitution, or lipid-lowering therapy combinations depending on a patient’s CVD risk and prevention needs.20 Other organizations make similar recommendations.1,15,21 Evidence from randomized trials suggests that many patients re-initiating therapy after a documented statin-related adverse event maintain treatment adherence.22–24 In the ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE trial, 67% of participants with intolerance to ≥2 statins who were re-initiated on atorvastatin remained on treatment over 6 months.25 The high likelihood for statin tolerability after re-initiation should be considered when balancing statin risks and benefits.

In the current study, high physical function was associated with an increased willingness to re-initiate therapy. Health conscious individuals may be more inclined to accept treatments that improve their CVD risk. In contrast, participants reporting SAMS, the most commonly reported side effect, were less likely to report willingness to re-initiate a statin. This is consistent with a qualitative study where primary care physicians reported SAMS as the most substantial barrier to statin re-initiation.26 Discussing the high percentage of people who can tolerate a statin despite having previously experienced side effects16 and encouraging shared decision making in re-initiating treatment may minimize this barrier. Higher LDL-C was also associated with being less willing to re-initiate a statin, which warrants further investigation. Listening to patients’ concerns, explaining the benefits of statins, and considering various therapeutic schedules may improve willingness to re-initiate treatment.27

Participants living in the stroke belt/buckle region of the US were more likely to report willingness to re-initiate a statin. Previous research reported low rates of statin adherence in the southeastern regions of the US relative to other regions, but did not focus on attitudes toward treatment re-initiation.28 Further research is warranted to investigate regional differences related to patterns of statin use. Willingness to re-initiate treatment did not differ between participants with and without a history of CVD or diabetes, two high risk populations likely to receive substantial CVD risk reduction benefits from taking statins. Discussing the CVD risk reduction benefits of statins may increase the willingness to re-initiate therapy among high risk groups.

The findings of the current study should be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. Statin use, the prevalence of discontinuation, and reasons for discontinuation were identified through self-report. Medical records were not available to confirm treatment patterns. The statin questionnaire was administered a median of 1.5 years after the second in-home examination. Duration of statin use, changes in statin type, titration prior to a participant discontinuing their statin, and the time at which a participant discontinued their statin was not available. The current analysis was cross-sectional and we were unable to account for changes in CVD risk over time, which may influence treatment decisions.

In conclusion, results from the current study indicate that over one third of individuals who discontinue a statin may be willing to re-initiate treatment. Even among participants who discontinued taking their statin due to side effects, a substantial percentage reported a willingness to re-initiate treatment. Healthcare providers should discuss treatment re-initiation with their patients who have discontinued taking a statin. Discussing side effects and tolerability, emphasizing the benefits of statins, and offering various therapeutic schedules may improve patients’ willingness to re-initiate a statin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The REGARDS research project is supported by a cooperative agreement U01NS041588 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Service. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke or the National Institutes of Health. Representatives of the funding agency have been involved in the review of the manuscript but not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.regardsstudy.org

Funding:

The current study was funded by an industry/academic collaboration between Amgen Inc., University of Alabama at Birmingham and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Additional support for GST was received through grant 5T32 HL00745733 from the NHLBI at the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosures: MTM, GST, RMT, and LDC have no disclosures. KLM works in the Center for Observational Research at Amgen and is a stockholder of Amgen. RD is employed by Amgen and is a stockholder of Amgen. MEF receives research support from Amgen. RSR receives research support from Akcea, Amgen, Medicines Company, and Sanofi. He has participated in Advisory Boards for Akcea, Amgen, Regeneron and Sanofi. He consults for C5 and CVS Caremark. He receives honoraria from Akcea, Kowa and Pfizer, and royalties from UpToDate. MMS receives research support from Amgen. She has participated in Advisory Boards for Amgen. PM receives has received grant support and honoraria from Amgen.

References

- 1.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, Goldberg AC, Gordon D, Levy D, Lloyd-Jones DM, McBride P, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC Jr., Watson K, Wilson PW, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2889–2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Holland LE, Reith C, Bhala N, Peto R, Barnes EH, Keech A, Simes J, Collins R. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010;376:1670–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prospective Studies Collaboration, Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet 2007;370:1829–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemstra M, Blackburn D, Crawley A, Fung R. Proportion and risk indicators of nonadherence to statin therapy: a meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol 2012;28:574–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGinnis B, Olson KL, Magid D, Bayliss E, Korner EJ, Brand DW, Steiner JF. Factors related to adherence to statin therapy. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:1805–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kashani A, Phillips CO, Foody JM, Wang Y, Mangalmurti S, Ko DT, Krumholz HM. Risks associated with statin therapy: a systematic overview of randomized clinical trials. Circulation 2006;114:2788–2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans MA, Golomb BA. Statin-associated adverse cognitive effects: survey results from 171 patients. Pharmacotherapy 2009;29:800–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Ito MK, Jacobson TA. Understanding Statin Use in America and Gaps in Patient Education (USAGE): an internet-based survey of 10,138 current and former statin users. J Clin Lipidol 2012;6:208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouchard MH, Dragomir A, Blais L, Berard A, Pilon D, Perreault S. Impact of adherence to statins on coronary artery disease in primary prevention. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:698–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simons LA, Simons J, McManus P, Dudley J. Discontinuation rates for use of statins are high. BMJ 2000;321:1084. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis JJ, Erickson SR, Stevenson JG, Bernstein SJ, Stiles RA, Fendrick AM. Suboptimal statin adherence and discontinuation in primary and secondary prevention populations. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:638–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei L, Wang J, Thompson P, Wong S, Struthers AD, MacDonald TM. Adherence to statin treatment and readmission of patients after myocardial infarction: a six year follow up study. Heart 2002;88:229–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guyton JR, Bays HE, Grundy SM, Jacobson TA, The National Lipid Association Statin Intolerance Panel. An assessment by the Statin Intolerance Panel: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol 2014;8:S72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banach M, Rizzo M, Toth PP, Farnier M, Davidson MH, Al-Rasadi K, Aronow WS, Athyros V, Djuric DM, Ezhov MV, Greenfield RS, Hovingh GK, Kostner K, Serban C, Lighezan D, Fras Z, Moriarty PM, Muntner P, Goudev A, Ceska R, Nicholls SJ, Broncel M, Nikolic D, Pella D, Puri R, Rysz J, Wong ND, Bajnok L, Jones SR, Ray KK, Mikhailidis DP. Statin intolerance - an attempt at a unified definition. Position paper from an International Lipid Expert Panel. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2015;14:935–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, Wiklund O, Chapman MJ, Drexel H, Hoes AW, Jennings CS, Landmesser U, Pedersen TR, Reiner Z, Riccardi G, Taskinen MR, Tokgozoglu L, Verschuren WMM, Vlachopoulos C, Wood DA, Zamorano JL, Cooney MT, E. S. C. Scientific Document Group. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2999–3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, Morrison F, Mar P, Shubina M, Turchin A. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:526–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenson RS, Baker S, Banach M, Borow KM, Braun LT, Bruckert E, Brunham LR, Catapano AL, Elam MB, Mancini GBJ, Moriarty PM, Morris PB, Muntner P, Ray KK, Stroes ES, Taylor BA, Taylor VH, Watts GF, Thompson PD. Optimizing Cholesterol Treatment in Patients With Muscle Complaints. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1290–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, Gomez CR, Go RC, Prineas RJ, Graham A, Moy CS, Howard G. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology 2005;25:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee KJ, Carlin JB. Multiple imputation for missing data: fully conditional specification versus multivariate normal imputation. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:624–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson TA, Ito MK, Maki KC, Orringer CE, Bays HE, Jones PH, McKenney JM, Grundy SM, Gill EA, Wild RA, Wilson DP, Brown WV. National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia: part 1 - executive summary. J Clin Lipidol 2014;8:473–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mancini GB, Baker S, Bergeron J, Fitchett D, Frohlich J, Genest J, Gupta M, Hegele RA, Ng D, Pearson GJ, Pope J, Tashakkor AY. Diagnosis, Prevention, and Management of Statin Adverse Effects and Intolerance: Canadian Consensus Working Group Update (2016). Can J Cardiol 2016;32:S35–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Backes JM, Venero CV, Gibson CA, Ruisinger JF, Howard PA, Thompson PD, Moriarty PM. Effectiveness and tolerability of every-other-day rosuvastatin dosing in patients with prior statin intolerance. Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruisinger JF, Backes JM, Gibson CA, Moriarty PM. Once-a-week rosuvastatin (2.5 to 20 mg) in patients with a previous statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol 2009;103:393–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mampuya WM, Frid D, Rocco M, Huang J, Brennan DM, Hazen SL, Cho L. Treatment strategies in patients with statin intolerance: the Cleveland Clinic experience. Am Heart J 2013;166:597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moriarty PM, Thompson PD, Cannon CP, Guyton JR, Bergeron J, Zieve FJ, Bruckert E, Jacobson TA, Kopecky SL, Baccara-Dinet MT, Du Y, Pordy R, Gipe DA, Odyssey Alternative Investigators. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab vs ezetimibe in statin-intolerant patients, with a statin rechallenge arm: The ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE randomized trial. J Clin Lipidol 2015;9:758–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanner RM, Safford MM, Monda KL, Taylor B, O’Beirne R, Morris M, Colantonio LD, Dent R, Muntner P, Rosenson RS. Primary Care Physician Perspectives on Barriers to Statin Treatment. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2017;31:303–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care 2009;47:826–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Couto JE, Panchal JM, Lal LS, Bunz TJ, Maesner JE, O’Brien T, Khan T. Geographic variation in medication adherence in commercial and Medicare part D populations. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014;20:834–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.