Abstract

We analyzed the serum antibody responses against two Staphylococcus aureus fibrinogen binding proteins, the cell-bound clumping factor (Clf) and an extracellular fibrinogen binding protein (Efb). The material consisted of 105 consecutive serum samples from 41 patients suffering from S. aureus septicemia and 72 serum samples from healthy individuals. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was developed. Healthy individuals showed variable levels of antibodies against the studied antigens, and cutoff levels (upper 95th percentile) against these antigens were determined. No correlation was seen between serum antibody levels against Clf and Efb. In acute-phase samples 27% of patients showed positive antibody levels against Clf and 10% showed positive levels against Efb, while in convalescent-phase samples 63% (26 of 41) showed a positive serology against Clf and 49% (20 of 41) showed a positive serology against Efb. Antibody levels against Efb were significantly lower in the acute-phase sera than in sera from healthy individuals (P = 0.002). An antibody response against Clf was most frequent in patients suffering from osteitis plus septic arthritis and from endocarditis (80% positive). The antibody response against Efb appeared to develop later in the course of disease. A possible biological effect of measured antibodies was demonstrated with the help of an inhibition ELISA, in which both high-titer and low-titer sera inhibited the binding of bacteria to fibrinogen. In conclusion, we have demonstrated in vivo production of S. aureus fibrinogen binding proteins during deep S. aureus infections and a possible diagnostic and prophylactic role of the corresponding serum antibodies in such infections.

The serological diagnosis of serious Staphylococcus aureus infections in the routine laboratory presently is based mainly on measuring antibodies against extracellular proteins, such as alpha-toxin or lipase, or against cell wall components, such as peptidoglycan, teichoic acid, or capsular material (4, 7, 8, 19). These antigens have been selected for serological diagnosis partly due to their possible role in bacterial virulence (17, 22). Recently, various surface-associated proteins of S. aureus, which might contribute to virulence and promote adherence to host cells and/or tissue components, have been described (9, 21, 24). Antibodies against these proteins also are formed during infection (3). Among these proteins, five fibrinogen binding proteins have been identified and characterized.

Fibrinogen is a 340-kDa glycoprotein found in high concentrations (3 mg/ml) in blood plasma. It is composed of three kinds of chains, α, β, and γ, which are linked together by disulfide bridges (2). Fibrinogen is proteolytically transformed into fibrin, which deposits in the wound matrix as fibrin fibers, and these also give form and structure to the blood clot. Furthermore, fibrinogen rapidly coats external surfaces of implanted biomaterials and thus contributes to bacterial attachment. Fibrinogen may coat the bacterial cell surface through attachment. It has been suggested that this bacterial coating may contribute to the evasion of host defenses (9).

Another important function of fibrinogen is to act as a cellular agglutinin, promoting interaction between several types of cells, such as staphylococci and streptococci, and also with platelets. These interactions involve binding to specific binding proteins on the cells. S. aureus cells form macroscopic clumps (clumping) when they are suspended in plasma. This reaction is the result of the avid binding of the dimeric plasma protein fibrinogen to the specific binding protein clumping factor (Clf) on the bacterial cell surface (11). Clf has been shown to be the major cause of S. aureus adhesion to fibrinogen (16).

Extracellular fibrinogen binding protein (Efb) is a constitutively produced 15.6-kDa protein and is one of three described fibrinogen binding proteins which are secreted into the medium (2, 21).

With the use of allele replacement mutants in experimental animal infection models, Clf has been shown to be of importance in endocarditis (18) and Efb has shown to play a role in the pathogenesis of wound infection (20). In an experimental mouse mastitis model, immunization with Efb was shown to give protection (15).

The aim of this study was to investigate whether patients with S. aureus septicemia produce antibodies against two antigen binding proteins, the cell surface-bound Clf and the extracellular Efb. A demonstrable antibody response would actually indicate that these proteins are produced in vivo and that the host immune system is exposed to them. The presence of an antibody response against these proteins may also add diagnostic information when patients with putative invasive S. aureus infection are being evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Forty-one patients with S. aureus septicemia admitted to the Department of Infectious Diseases, Örebro Medical Center Hospital, were included and have been described earlier (8). The clinical diagnosis of S. aureus septicemia was verified by at least two positive blood cultures with the Bactec 660 HP system (Becton Dickinson, Paramus, N.J.). The mean age of the septicemic patients was 65 years (range, 13 to 93 years). Serum samples were collected sequentially (n = 105) and stored at −70°C until analysis. Acute-phase samples were drawn <8 days and convalescent-phase serum samples were drawn 14 to 30 days after onset of disease. The S. aureus septicemia patients were divided according to complicating infections, as follows: all endocarditis cases (n = 10), osteomyelitis cases except those with endocarditis (n = 8), joint infection and septic arthritis (n = 12), abscesses only (n = 4), and uncomplicated cases (n = 7).

Serum samples (n = 38) from 20 patients, 32 to 96 years old (mean, 70 years) with septicemia due to etiological agents other than S. aureus were used as controls. The bacteria isolated from these patients were Streptococcus pneumoniae (n = 8), Escherichia coli (n = 6), Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 2), Klebsiella oxytoca (n = 1), Staphylococcus epidermidis (n = 1), an Enterobacter sp. (n = 1), and Streptococcus pyogenes group A (n = 1).

Serum samples (n = 72) from healthy controls 21 to 68 years old (mean, 49 years) were used for the determination of antibody levels in a normal population.

Production of fibrinogen binding proteins.

Clf was purified from E. coli XL-1 harboring plasmid pCF33 (kindly supplied by T. J. Foster, Dublin, Ireland), derived from pQE30 (Qiagen, Basel, Switzerland), expressing a His6 fusion protein. This 42-kDa fusion protein contains residues 221 to 550 of the ClfA region that has the fibrinogen binding domain. The His6-Clf fusion protein was purified by using nickel chelator according to the instruction provided by Qiagen.

Efb was purified from S. aureus (strain Newman) as described earlier (21). One liter of S. aureus culture was grown overnight at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium. The culture was centrifuged to pellet cells, and fibrinogen binding proteins in the supernatant were isolated by affinity chromatography on fibrinogen-Sepharose (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Bound proteins were eluted with 0.7% acetic acid and dialyzed against 40 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5), and the different fibrinogen binding proteins were separated from each other by fast protein liquid chromatography on a Mono-S column. Elution with a gradient of 0 to 1 M NaCl resulted in three peaks of protein. The N terminus from each peak was sequenced and analyzed: the N-terminal sequence from the first peak corresponded to the coagulase sequence, that from the second peak (0.35 to 0.45 M NaCl) corresponded to Efb, and that from the third peak corresponded to an unrelated protein. Further identification of the second peak was done by immunoblotting with specific rat anti-Efb (21).

ELISA.

Coating concentrations were 2 μg/ml for Clf and 0.6 μg/ml for Efb. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method has been described earlier (25). The working volume was 100 μl, and after each step the microplates were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) (PBS) plus 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T). Briefly, microplates were coated with the appropriate antigen diluted in PBS and incubated overnight at 20°C. Serum samples diluted in PBS-T were applied and incubated for 1 h at 37°C; each patient sample was titrated in a twofold dilution (1/500 to 1/16,000). Alkaline phosphatase conjugated to goat anti-human antibodies (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) diluted 1/2,000 in PBS-T was then added, and incubation was continued for 1 h at 37°C. For every two plates, three control sera (two positive and one negative) and a reference serum (consisting of pooled sera from six patients with confirmed sepsis) were included. The control sera were used in a single dilution in duplicate wells, and the reference serum was titrated like the patient samples. After the final wash, the reaction was developed by the addition of p-nitrophenylphosphate substrate (Sigma Chemical Co.). The enzymatic reaction was measured at 405 nm in a Titertek Multiscan microplate reader (Flow Laboratories, Irvine, Scotland) after 45 min of incubation for Clf and after 20 min for Efb. The data were transmitted online from the reader to a computer, and calculations were performed with the Unitcalc software (PhPlate Stockholm AB, Stockholm, Sweden).

Interpretations of ELISA results.

In order to be able to perform comparative calculations with the ELISA results, the obtained absorbance values were transformed into arbitrary units by using the reference line units calculation method (23). The dilution curve of each sample was made parallel to that of the reference serum, after which the two curves were compared. The reference serum was given the value of 1,000 U for both antigens (Unitcalc software; PhPlate Stockholm), and the serum antibody levels were expressed in these units. A level of 2,000 U in a sample thus means that this sample could be diluted to twice the dilution of the reference serum, as compared with the dilution curves. The lowest level to be included in the calculations was 60 U. The upper limit for normal antibody levels was established with the healthy controls. The upper cutoff level was set at the upper 95th percentile. Levels above this cutoff level are here designated high level, and a significant rise of antibody levels is defined as a twofold increase (or decrease in a few cases) compared to that in the acute-phase serum sample, providing at least one serum level above a lower threshold value of 120 U (2 × 60 U). A patient was considered to show a positive serology when a high level in at least one serum sample and/or a significant rise of antibody levels was noted.

Inhibition ELISA.

In order to understand the biological effect in vivo of patients' antibodies against these antigens (Clf and Efb), we designed an inhibition ELISA with the purpose of measuring the effect of patient sera on bacteria attached to fibrinogen and on free bacteria. We tested this assay on sera from septicemia patients and from healthy individuals.

One loopful of S. aureus (strain Wood 46, which is low in protein A content) was cultivated in brain heart infusion overnight at 37°C, the culture was washed with PBS, and a final bacterial suspension (optical density of 0.55 at 660 nm) was prepared in PBS. Each sample was run on two plates in parallel, one reference plate and one inhibition plate; both plates were precoated with fibrinogen (1 μg/ml) (Sigma, Chemical Co.). In the reference plate, 100 μl of the bacterial suspension was added to the wells and allowed to adhere for 2 h at 37°C. After washing, patient sera were added in twofold dilutions from 1/250 to 1/8,000 and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. In the inhibition plate, the bacterial suspension was preincubated with patient sera in the same dilutions for 1 h at 37°C prior to the addition to the fibrinogen-coated wells, after which the bacteria were allowed to adhere for 2 h at 37°C. For both plates, detection of bound bacteria was performed, after washing, with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human antibodies as for the ELISA described above. Thus, the inhibition ELISA measures the difference in attachment of bacterial cells to fibrinogen in the absence and in the presence of serum antibodies.

Statistical methods.

Student's exact t test, the Wilcoxon paired test, the Wilcoxon two-sample test, and two-by-two table chi-square analysis were performed with the computer program Statgraphics, version 2.6 (STSC, Rockville, Md.), as was the determination of Spearman correlation coefficients and their significance.

RESULTS

Antibodies against Clf and Efb in a healthy control population.

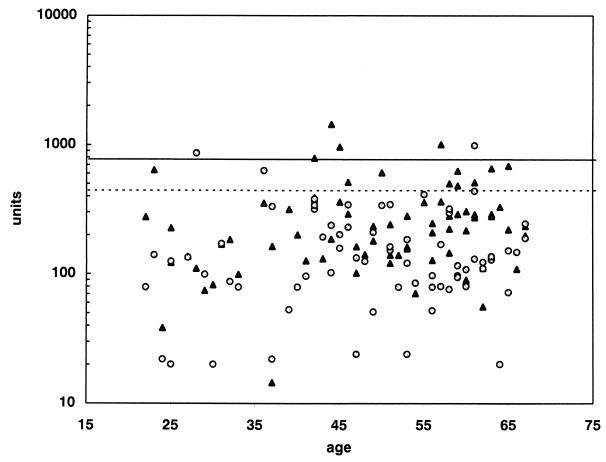

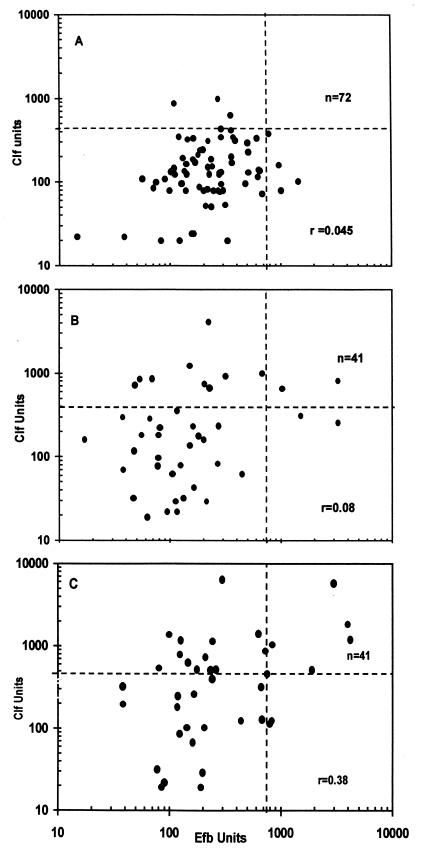

Antibody levels against Clf and Efb in a healthy control population (n = 72) were estimated (Fig. 1). No age-correlated variation was found, and therefore a common upper cutoff limit was used without age corrections. The upper limit, corresponding to the 95th percentile, was 440 U for Clf and 750 U for Efb. No correlation between the Clf and Efb antibody levels in this population was seen (r = 0.045) (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 1.

Antibody responses against Clf (○) and Efb (▴) in a healthy control population. The upper 95th percentiles are marked by a dotted line for Clf and by a solid line for Efb.

FIG. 2.

Comparisons of antibody levels against Clf and Efb in a healthy control population (A), in acute-phase samples from septicemic patients (B), and in convalescent-phase samples from the same patients (C). Dashed lines indicate upper 95th percentiles.

Antibodies against Clf in septicemic patients.

In 20 of 41 patients with S. aureus septicemia, the antibody levels in the convalescent-phase serum exceeded the cutoff limit, and 16 of 41 patients showed a significant rise in antibody levels. A total of 26 patients (63%) were considered serologically positive. In acute-phase serum samples, high levels were found in 11 of 41 patients (Fig. 2B). Among patients with non-S. aureus septicemia, 2 of 20 patients showed a positive antibody response against Clf in their convalescent-phase samples.

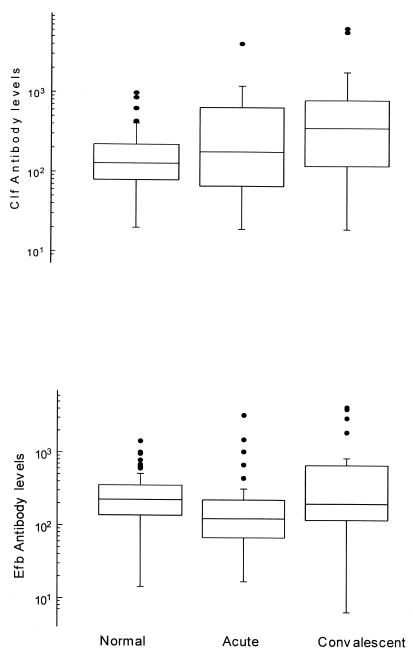

The mean antibody level in acute-phase sera (180 U) was higher than the mean level found in the healthy population (129 U) (P = 0.009). The levels during the convalescent phase were significantly higher (360 U) than those during the acute phase (P = 0.0004) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Box plots of antibody levels against Clf (top) and Efb (bottom) in healthy and septicemic individuals. The box comprises 50% of the individuals, and the vertical lines comprise the individuals within the area representing twice that of the box height. The horizontal line in each box represents the median value.

Antibodies against Efb in septicemic patients.

The antibody response in the patients appeared to be weaker against Efb than against Clf, as compared to the respective antibody levels in the normal population. In acute-phase sera only 4 patients were positive with high levels, and in the convalescent-phase sera only 9 patients showed high levels, in contrast to 20 patients for Clf (P < 0.02) (Fig. 2B). However, in total 20 of 41 patients (49%) were serologically positive when the rise in levels in serum was considered. Among patients with non-S. aureus septicemia, 3 of 20 showed a positive antibody response.

In contrast to the case for the Clf levels, the mean Efb level in acute-phase sera (124 U) was significantly lower than the mean level found in the healthy population (224 U) (p = 0.002). In the convalescent phase the level increased to 200 U, which was a significant rise (P = 0.00017) (Fig. 3).

Combination of Clf and Efb.

When the results for the two antigens were combined, 29 of 41 patients (71%) were serologically positive to at least one of the studied antigens, and of these all but 3 (63%) showed a significant rise in antibody levels against at least one of the antigens. One-third of the patients were already positive in their acute-phase sample. Most patients increased their antibody levels to both antigens, as indicated by the statistically significant correlation coefficient for the levels in the convalescent-phase sera (r = 0.38; P < 0.02) (Fig. 2C).

Antibody response in relation to type of infection.

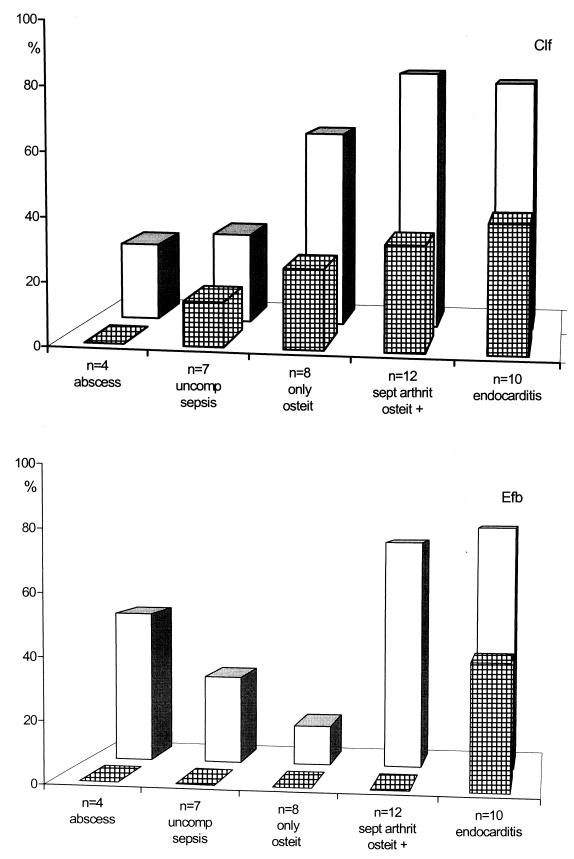

The serological response against Clf was higher and occurred earlier than the response against Efb. About 80% of both patients with osteitis plus septic arthritis and those with endocarditis were positive (Fig. 4). The greatest increase in the percentage of positive patients was found in those with bone and joint infections (0 to 75%) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Antibody response in various kinds of infections. Cross-hatched bars indicate the percentage of patients in the respective disease group that show a positive serology in their acute-phase sera, and open bars indicate the percentage of patients positive in convalescent-phase sera. uncomp, uncomplicated; osteit, osteitis; sept arthrit, septic arthritis.

Inhibition of bacterial binding to fibrinogen.

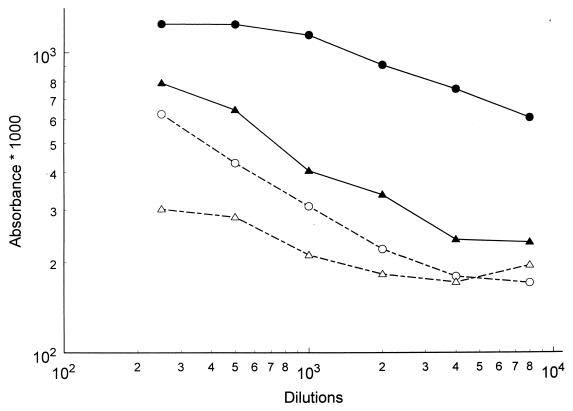

Bacteria were bound to immobilized fibrinogen with and without preincubation with patient sera, and binding was detected by the same sera. It was evident that both high-titer and low-titer sera inhibited the binding to fibrinogen to various extents (Fig. 5), thus indicating a possible biological effect of the measured antibody levels.

FIG. 5.

Serum inhibition of bacterial binding to fibrinogen. Fibrinogen was immobilized to microplate wells. Binding of staphylococcal cells (closed symbols) was measured through addition of bacteria to these microplates, and the amount of bound cells was then estimated through secondary addition of patient sera in different dilutions. In parallel experiments inhibition of this binding by patient antibodies (open symbols) was measured through addition of bacteria that had been preincubated with the same serum dilutions to the microplates. In both experiments conjugated antibodies against human IgG were then added. Circles indicate a high-titered patient convalescent serum, and triangles indicate a low-titer patient serum. Inhibition by both sera is clearly seen.

DISCUSSION

Surface-associated proteins of S. aureus and their possible roles as virulence factors have been studied with various animal models (15, 18, 20). However, knowledge about the serological response against these proteins in patients suffering from deep S. aureus infections was lacking (3). Studies on antibody levels against potential vaccine candidates in health and disease are important for the development of an effective multicomponent vaccine against deep infections caused by S. aureus (14). In the present study we analyzed the serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) responses against two fibrinogen binding proteins of S. aureus: Clf, which is expressed mainly on the bacterial surface, and Efb, which is an extracellular protein.

In a healthy population we found the same pattern as with other S. aureus antigens, namely, that healthy individuals show highly variable levels (100-fold variation) of serum antibodies against the studied antigens (Fig. 1), but all individuals had detectable IgG levels. Similar results are found with other staphylococcal antigens, such as alpha-toxin (8, 10), lipase (26), enterotoxins (12), toxic shock syndrome (TSS) toxin (1), teichoic acid (8, 10), and peptidoglycan (4), which indicates previous experience of staphylococcal infections and thereby antibodies raised against these antigens in the population. The presence of detectable antibody levels, both in the normal population and in patients, clearly indicates that these two fibrinogen binding proteins are expressed by S. aureus in vivo.

In most of the previous studies on antibody responses to various S. aureus antigens, the antibody levels have been expressed as absorbances (titers) in a one-dilution indirect ELISA (8, 10), thus making interlaboratory comparisons and meaningful calculations difficult. In the present study, each serum was titrated in six twofold dilutions, and correlation curves were calculated. They were in turn referred to results for a standard serum given arbitrary units (23). This method facilitates interlaboratory comparisons when the same standard serum is used. Furthermore, the units obtained represent true titers; i.e., they indicate how many times the tested serum can be diluted in order to give the same curve as the standard serum. Such titers are “calculable”; i.e., a doubling of units between acute- and convalescent-phase sera actually indicates that the convalescent-phase serum can be diluted one twofold dilution step further than the acute-phase serum. This can not be stated for absorbance values.

The poor correlation between the IgG levels against Clf and Efb in the normal population (Fig. 2) indicates that the measured antibodies were independently produced, and thus these two antigens could give us complementary diagnostic serological information. In fact, with alpha-toxin and teichoic acid as antigens with the patients sera, 73% of the patients were deemed serologically positive (8), and the use of Clf and Efb as antigens resulted in 71% of the patients being deemed positive. Accordingly, combining all four antigens raised the percentage of positive patients to 88% (data not shown).

The kinetics of the antibody responses against the two studied antigens were different. Clf showed the expected kinetics, with a rapid onset of antibody production, seen as high levels in the acute-phase sera, and an expected further rise in antibody levels during the disease. In contrast, antibody levels to Efb were significantly lower in the acute-phase sera than in the normal population, and only four patients, who were suffering from endocarditis, showed serum IgG levels above the cutoff level (Fig. 3 and 4). Although the IgG levels increased during disease, the average level in the convalescent-phase sera still barely reached that of the normal population (Fig. 3).

These differences might be due to a weaker stimulation of the immune system by the Efb antigen than by the Clf antigen, but this explanation seems less probable since the antigens appear to induce similar levels of antibodies in the normal population. Alternatively, the formed antibodies may form complexes with freely circulating antigen. This complex formation may cause a consumption of serum antibodies, rendering them not detectable in the ordinary ELISA. This consumption might be more pronounced for the extracellularly released Efb than for the cell-bound Clf, a phenomenon which would result in the observed differences in antibody levels during an active infection. However, the difference may also reflect the fact that individuals with a weaker antibody production against Efb are more prone to develop deep (or serious) staphylococcal infections. Such a possible relation between infection susceptibility and antibody formation was reported earlier for S. aureus alpha-toxin (8), and a recognized correlation between low antibody levels and disease susceptibility exists for TSS toxin and TSS (1, 5). The polysaccharide capsules of certain S. aureus strains have been implicated as a virulence factor that is neutralized by specific antibodies (13).

The earlier response against Clf than against Efb during the course of disease reminds one of the fact that Clf may be produced to anchor the cell to fibrinogen (and fibrin) deposits, probably early in the infectious phase, while Efb is constitutively produced and reaches larger amounts at a later phase, probably inhibiting attachment by Clf and thereby facilitating the spread of bacteria (22). The most probable reason is that patients with lower antibody levels, whether or not they reflect a decreased ability to produce the particular antibodies, are at a higher risk to develop a deep infection with S. aureus (14).

Although the number of samples is too small for division into subgroups, Fig. 4 indicates that certain complications give rise to a more pronounced antibody response than others. Uncomplicated sepsis was shown by Colque-Navarro and coworkers, using the same patients, to give rise to comparatively higher antibody titers against alpha-toxin and teichoic acid (8), but against the fibrinogen binding antigen, the response was opposite. Instead, patients suffering from osteitis in connection with arthritis and patients with endocarditis showed the most evident serological response (83 and 80%, respectively, with both antigens). Patients with osteitis only and with abscesses showed a weaker response (63 and 50%, respectively), which is in concordance with earlier observations on other antigens (10).

Thus, this study has shown that the two fibrinogen binding proteins Clf and Efb are produced in vivo, that antibodies against them are present to various extents in the normal population, and that increased levels are achieved upon S. aureus infections in many cases. During the disease, such an increase in antibody levels is seen earlier for Clf than for Efb. In fact, acute-phase sera from patients show lower mean IgG levels against Efb than in the normal population. The patient sera inhibited the binding of S. aureus bacterial cells to immobilized fibrinogen in parallel with the measured IgG levels, a finding which indicates a possible biological effect of these antibodies. Furthermore, the antibodies against Clf were measured against a recombinant molecule representing mainly the fibrinogen binding domain. The studies indicate that Clf and Efb should be considered in future work with immunoprophylactic tools against deep infections with S. aureus. The opsonizing effect of IgG against cell-bound antigens is considered to be of outmost importance in the host defense against S. aureus infections (14), and it is conceivable that antibodies against cell-bound fibrinogen binding proteins, like Clf, would act as such.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergdoll M, Crass B A, Reiser R F, Robbins R N, Davis J P. A new Staphylococcal enterotoxin, enterotoxin F, associated with toxic-shock-syndrome Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Lancet. 1981;i:1017–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodén M, Flock J I. Evidence for three different fibrinogen-binding proteins with unique properties from Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman. Microb Pathog. 1994;12:289–298. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90047-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casolini F, Visai L, Joh D, Conaldi P G, Toniolo A, Höök M, Speziale P. Antibody response to fibronectin-binding adhesin FnbpA in patients with Staphylococcus aureus infections. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5433–5442. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5433-5442.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensson B, Espersen F, Hedström S Å, Kronwall G. Serological assays against Staphylococcus aureus peptidoglycan, crude staphylococcal antigen and staphylolysin in the diagnosis of serious S. aureus infections. Scand J Infect Dis. 1985;17:47–53. doi: 10.3109/00365548509070419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensson B, Hedström S Å. Serological response to TSS toxin in Staphylococcus aureus infected patients and in healthy controls. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand. 1984;93:87–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1985.tb02857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensson B, Boutounnier A, Ryding U, Fournnier J-M. Diagnosing Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis by detecting antibodies against S. aureus capsular polysacharide types 5 and 8. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:511–515. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensson B, Hedström S Å, Kronwall G. Antibody response to alpha and beta hemolysin from Staphylococcus aureus in patients with staphylococcal infections and in normals. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand. 1983;91:351–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1983.tb00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colque-Navarro P, Söderquist B, Holmberg H, Blomqvist L, Olcén P, Möllby R. Antibody response in Staphylococcus aureus septicemia—a prospective study. Med Microbiol. 1998;47:217–225. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-3-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster T, McDevitt D. Surface-associated proteins of Staphylococcus aureus: their possible roles in virulence. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;118:199–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granström M, Julander I, Möllby R. Serological diagnosis of deep Staphylococcus aureus infections by ELISA for staphylococcal hemolysins and teichoic acid. Scand J Infect Dis. 1983;41:132–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawiger J, Kloczewiak M, Timmons S, Strong D, Doolittle R F. Interaction of fibrinogen with staphylococcal clumping factor and with platelets. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1983;408:521–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1983.tb23270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanclerski K, Söderquist B, Kjellgren M, Holmberg H, Möllby R. Serum antibody response to S. aureus enterotoxins and TSST-1 in patients with septicemia. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:171–177. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-3-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J C, Perez N E, Hopkins C A, Pier G B. Purified capsular polysaccharide-induced immunity to Staphylococcal infections. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:723–729. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.4.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J C, Pier B P. Vaccine-based strategies for prevention of Staphylococcal diseases. In: Crossley K B, Archer G L, editors. The staphylococci in human disease. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 631–654. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mamo W, Bodén M, Flock J I. Vaccination with Staphylococcus aureus fibrinogen binding proteins (Fg Bps) reduces colonization of S. aureus in a mouse mastitis model. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1994;10:47–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1994.tb00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDevitt D, Francois P, Vadaux P, Foster T J. Identification of the ligand-binding domain of the surface-located fibrinogen receptor (clumping-factor) of the Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:895–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Möllby R. Antibody response in deep Staphylococcus aureus infections. In: Möllby R, Flock J I, Nord C E, Christensson B, editors. Staphylococci and staphylococcal infections. Stuttgart, Germany: Gustav Fischer Verlag; 1994. pp. 451–459. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moreillon P, Entenza J M, Francioli P, Foster T J, Francois P. Role of Staphylococcus aureus coagulase and clumping factor in pathogenesis of experimental endocarditis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4738–4743. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4738-4743.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagel J G, Tuazon C U, Cardella T A, Sheagren J N. Teichoic acid serological diagnosis of staphylococcal endocarditis. Ann Intern Med. 1975;82:13–17. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-82-1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palma M, Nozohoor S, Schennings T, Heimdahl A, Flock J I. Lack of the extracellular 19-kilodalton fibrinogen-binding protein from Staphylococcus aureus decreases virulence in experimental wound infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5284–5289. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5284-5289.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palma M, Wade D, Flock M, Flock J I. Multiple binding sites in the interaction between an extracellular fibrinogen-binding protein from Staphylococcus aureus and the fibrinogen. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13177–13181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Projan S J, Novick R P. The molecular basis of pathogenicity. In: Crossley K B, Archer G L, editors. The staphylococci in human disease. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reizenstein E, Hallander H O, Blackwelder W C, Kühn I, Ljungman M, Möllby R. Comparison of five calculation models for antibody ELISA procedures, using pertussis serology as a model. J Immunol Methods. 1995;183:279–290. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00067-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryding U, Flock J I, Flock M, Söderquist B, Christensson B. Expression of collagen-binding protein and types 5 and 8 capsular polysacharide in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1096–1099. doi: 10.1086/516520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Söderquist B, Colque-Navarro P, Blomqvist L, Olcén P, Holmberg H, Möllby R. Staphylococcal α-toxin in septicaemic patients; detection in serum, antibody response and production in isolated strains. Serodiagn Immunother Infect Dis. 1993;5:139–144. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyski S, Colque-Navarro P, Hryniewicz W, Granström M, Möllby R. Lipase versus teichoic acid and alpha-toxin as antigen in an enzyme immunoassay for serological diagnosis of Staphylococcus aureus infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:447–449. doi: 10.1007/BF01968027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]