Abstract

This research investigates the effects of several measures of Twitter-based sentiment on cryptocurrencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Innovative economic, as well as market uncertainty measures based on Tweets, along the lines of Baker et al. (2021), are employed in an attempt to measure how investor sentiment influences the returns and volatility of major cryptocurrencies, developing on non-linear Granger causality tests. Evidence suggests that Twitter-derived sentiment mainly influences Litecoin, Ethereum, Cardano and Ethereum Classic when considering mean estimates. Moreover, uncertainty measures non-linearly influence each cryptocurrency examined, at all quantiles except for Cardano at lower quantiles, and both Ripple and Stellar at both lower and higher quantiles. Cryptocurrencies with lower values are found to be unaffected by investor sentiment at extreme values, however, prove to be profitable due to more aligned investor behaviour.

Keywords: Sentiment, Uncertainty, Cryptocurrencies, COVID-19, Pandemics, Black Swans

1. Introduction

Cryptocurrencies have generated much debate surrounding whether the disintermediation and online technological progression of finance at a worldwide level merits the levels of risk that have been generated through additional factors such as cybercriminality, regulatory ambiguity, fraud, manipulation, and broad propensity to generate irrational exuberance (Akyildirim et al., 20 Akyildirim et al., 2021, Gandal et al., 2021). These matters have drawn even larger opprobrium due to the development of the COVID-19 pandemic that started as a health crisis and rapidly developed into a global financial crisis. This pandemic has generated substantial global financial market volatility and has driven investors to seek alternative assets to preserve their portfolios at a satisfactory risk-return trade-off level. Cryptocurrencies have attracted speculators as well as technology-fluent investors (Lee et al., 2020), some of which have been attracted through the product validation provided by several widely known public figures and corporations, many of whom have had limited, if not no experience at all developing and selling technologically developed products (Akyildirim et al., 2020, Cioroianu et al., 2021, Fletcher et al., 2021). As an asset, cryptocurrencies have been considered to be primarily employed for speculation purposes but not as an alternative currency and medium of exchange (Fry, 2018, Kyriazis et al., 2020).

Investigating the determinants of the returns and volatility of cryptocurrencies has been the focus of a broad number of academic studies (Dyhrberg et al., 2018, Eross et al., 2019, Katsiampa, 2017, Katsiampa et al., 2019a, Katsiampa et al., 2019b, Akyildirim et al., 2020 Akyildirim et al., 2021, Papadamou et al., 2021, Sensoy et al., 2021). This research sets out to build on this work, and further investigate whether non-linear causal linkages exist between Twitter-derived measures of economic and market uncertainty and the largest cryptocurrencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. These Twitter-based measures of investor sentiment developed by Baker et al. (2021), advance the already-existing and highly popular Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) indices. To construct the TEU-USA indicator, the authors tokenize and use the lower-case versions of all tweets in their sample, while counting the frequency of tweets that contain keywords related to the economy1 . Further, duplicate tweets are removed, and only those that combine economic and uncertainty terms remain in the sample after the Random Forecast Classifier is used to distinguish whether the US is the location of the tweets or not. The impacts of these innovative measures of investor sentiment on cryptocurrency mean and volatility are investigated by employing the highly-sophisticated non-linear quantile causality methodology of Diks and Panchenko (2006). This is considered to be more advanced than the conventional Granger causality methodology and can distinguish non-linear impacts that are far from easily discernible when traditional methodologies are employed. Econometric estimations are undertaken to cover the full period of the COVID-19 pandemic from its beginnings in January 2020 to the present. This study is related to previous academic work investigating the impacts of uncertainty measures on cryptocurrencies (Fang et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2020) and the linkages of COVID-19 with financial markets (Conlon et al., 2020, Raheem, 2021, Sarkodie et al., 2021).

This study is the first to scrutinise the effects of such a large range of innovative uncertainty indices upon the returns and volatilities of cryptocurrencies, specifically shedding light upon the nexus between Twitter-based investor sentiment, digital forms of liquidity and investment, and the COVID-19 pandemic, providing investors with beneficial insights to support the development of more accurate decision-making through adverse conditions. Presented results indicate that Bitcoin, Ethereum, Bitcoin Cash, and Litecoin are non-linearly influenced in the mean by the selected Twitter-derived economic uncertainty indices. However, only Ethereum, Bitcoin Cash, and Cardano are found to be non-linearly caused in the mean by Twitter-based market uncertainty measures. The majority of analysed cryptocurrencies are found to be receivers of uncertainty influence at all quantiles investigated, however, those with low nominal values appear to remain unaffected by Twitter-derived sentiment indicators. Such a phenomenon could be very useful for hedging purposes in portfolios that consist of modern or traditional financial assets, where some cryptocurrencies can serve as safe-havens during turbulent economic and market conditions. Such results are found to be robust when considering alternative methodological specifications.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a concise review of the literature, along with an explanation surrounding the connection between EPU uncertainty measure’s interactions with financial markets. Section 3 presents an overview of the data and an explanation of the methodology which has been adopted for estimation. Section 4 presents an overview of the results, while Section 5 concludes and suggests avenues for further research.

2. Literature review

A significant number of academic papers have focused on the investigation of investor sentiment within the structures of modern financial assets. This study contributes to four specific strands of academic research surrounding this area. First, we focus on the impact of economic policy uncertainty on cryptocurrencies. Specifically, Wang et al. (2020) provide evidence that higher levels of EPU lead to higher cryptocurrency returns. US EPU is revealed to result in elevated Bitcoin volatility and trading volume after EPU spikes while UK EPU is found not to be as influential. Moreover, direct spillovers from US EPU to UK EPU are detected. Beneki et al. (2019), argued that economic policy uncertainty strengthens the connection between Bitcoin and Ethereum and provides weak diversification benefits regarding portfolio performance. In a somewhat different perspective, Fang et al. (2020) note a connection between news-based implied volatility and a direct influence upon the long-term volatility of five major cryptocurrencies in both a negative and significant manner. This result is also found to be valid when the Global Economic Policy Uncertainty index is considered. Investor sentiment is revealed to be more important than economic fundamentals to predict cryptocurrency volatility. Apart from strictly focusing on economic policy uncertainty, studies related to geopolitical uncertainty effects or trade uncertainty impacts on cryptocurrencies have had a central role in previous literature development. Gozgor et al. (2019) identify a significant relationship that runs from US Trade Policy Uncertainty (TPI) to Bitcoin returns and presents further evidence of regime changes during the periods between 2010-11 and 2017-18. This connection is revealed to be powerful during regime changes. Further, Baker et al. (2021) make the extension of their Economic Policy Uncertainty index by focusing on tweets to derive investor sentiment. They create four innovative economic sentiment indices and four market sentiment indices that are all based on tweets, arguing that Twitter users bear large similarities with journalist perceptions about risk and uncertainty. Moreover, Lehrer et al. (2021) perform an out-of-sample exercise and reveal that when social media sentiment is included then the forecast accuracy of a popular volatility index can be improved, especially in the short run. High-frequency data are found to be favourable for forecasting. Further, Tumasjan et al. (2021) argue that there is a positive linkage between signalling and venture capital valuation, but Twitter sentiment is not found to be related to investment success in the long run.

A series of relevant papers that focus on impacts of Twitter-based investor sentiment on cryptocurrencies includes that of Philippas et al. (2019), who examine whether Bitcoin price jumps are related with Twitter and Google Trends informative signals. Outcomes by the dual diffusion model adopted reveal that Bitcoin market values are partially led by the momentum of media attention in social networks, and investors ask for information to make investing decisions. Similarly, Li et al. (2021) identified that bi-directional causalities and spillovers exist among the majority of the twenty-seven cryptocurrencies investigated and investor attention. It is underlined that when investor sentiment is based on a combination of Twitter and Google search data, these interlinkages are more obvious. Huynh (2021) assessed the impact of President Trump’s tweets on Bitcoin price and trading volume, arguing that negative sentiment tweets prove to be considerably more powerful than positive ones as concerns the predictive power about returns, trading volume, realised volatility and jumps in Bitcoin markets. Kraaijeveld and De Smedt (2020) focus on the predictive powers of Twitter sentiment and adopt a lexicon-based sentiment analysis and bilateral Granger causality for studying the nine largest cryptocurrencies. It is revealed that Twitter significantly affects the returns of Bitcoin, Bitcoin Cash and Litecoin, while also EOS and TRON if a bullishness ratio is employed. Further, Wu et al. (2021) adopted the Twitter-based EPU and TMU measures and reveal that the Twitter-derived economic uncertainty significantly influences the Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Ripple values expressed in US dollars. These impacts are found to be positive. Moreover, Naeem et al. (2021) centre their interest on the FEARS index and the Twitter sentiment index and argue that the happiness sentiment is a stronger predictor of cryptocurrency returns. Predictability is found to be driven mostly by social media sentiment rather than macroeconomic news. Furthermore, Umar et al. (2021) employ a range of sentiment indicators to find which better expresses the bubble phenomenon of GameStop. Media-driven sentiment indicators reveal the large levels of inefficiency that investors could create in markets2 . Social media platforms could be useful for monitoring such investing behaviour. Finally, Béjaoui et al. (2021) argue that there is a strong dynamic nexus between Bitcoin and social media that also holds during the COVID-19 era, both social media and Bitcoin prices are revealed to be influenced by a considerable extent of this health crisis.

Conlon et al. (2020) support that Bitcoin and Ethereum do not constitute a safe haven regarding the majority of international equity indices investigated and when these digital currencies are included in portfolios they result in higher downside risk. However, Tether is revealed to exhibit some safe-haven characteristics towards several examined indices3 . Guo et al. (2021) find that the COVID-19 crisis has led to a stronger contagion effect between Bitcoin and developed markets. It is identified that both US and European markets remain contagion sources to Bitcoin while gold, the US dollar and bond markets are identified as receivers of contagion effects. The pandemic is also found to have weakened the diversifying, hedging or safe haven properties of Bitcoin. Goodell and Goutte (2021) identified that the COVID-19 pandemic positively influences Bitcoin market values. This phenomenon is more obvious after the March 2020 crash in financial markets. Furthermore, Huang et al. (2021), through the application of a Bayesian Panel-VAR methodology reveal that major economies enjoy diversification benefits and risk mitigation within and across borders due to Bitcoin during the COVID-19 era4 .

3. Data & methodology

Estimations take place during the period since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, designated as the official WHO announcement identifying the existence of an international pandemic on 1 January 2020, through the period ending 25 July 2021. To conduct econometric estimations to detect causality, eight Twitter-derived uncertainty measures have been used5 . These indices are based on the work of Baker et al. (2021), and consist of four economic uncertainty indices (TEU-ENG, TEU-USA, TEU-WGT, and TEU-SCA) and four market uncertainty indices (TMU-ENG, TMU-USA, TMU-WGT, and TMU-SCA), where TEU stands for Twitter Economic Uncertainty and TMU represents Twitter Market Uncertainty6 . Moreover, daily data based on the ten largest cryptocurrencies by market capitalisation during the examined period are adopted for our empirical estimations7 . More specifically, the largest cryptocurrencies by capitalisation examined are Bitcoin (BTC), Ethereum (ETH), Binance Coin (BNB), Cardano (ADA), Ripple (XRP), Dogecoin (DOGE), Bitcoin Cash (BCH), Litecoin (LTC), Ethereum Classic (ETC), and Stellar (XLM).

Table 1 illustrates the descriptive statistics of the variables under scrutiny in this study. It is observed that all examined cryptocurrencies exhibit positive returns on average. Notably, Dogecoin is found to present the largest returns but also represents the most volatile digital asset. Cardano and Binance Coin follow in terms of returns whereas Ripple in terms of fluctuations. Emphasis should also surround the fact that all digital currencies present high levels of volatility and kurtosis. High levels of non-normal distribution are also revealed by the Jarque-Bera statistic, presenting evidence that non-linear estimation in quantiles could prove more useful for identifying causality in relation to conventional Granger causality. Moreover, it is noticeable that the DF-GLS and the Phillips-Perron tests indicate stationarity of all variables when the first differences of series are adopted.

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

| Variable | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | JB | DF-GLS | PP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEU-ENG | − 0.0006 | 0.2088 | 0.245 | 4.118 | 393.59*** | − 2.58*** | − 733.44*** |

| TEU-USA | − 0.0012 | 0.3215 | 0.073 | 4.904 | 550.8*** | − 2.28** | − 793.55*** |

| TEU-WGT | − 0.0005 | 0.3671 | 0.019 | 3.671 | 308.34*** | − 2.83*** | − 809.13*** |

| TEU-SCA | − 0.0015 | 0.3392 | 0.195 | 3.815 | 336.54*** | − 2.13** | − 792.07*** |

| TMU-ENG | − 0.0009 | 0.2595 | 0.155 | 4.387 | 442.64*** | − 2.68*** | − 722.76*** |

| TMU-USA | − 0.0004 | 0.3755 | 0.145 | 2.859 | 188.95*** | − 2.62*** | − 722.44*** |

| TMU-WGT | − 0.0004 | 0.4031 | 0.077 | 2.542 | 148.41*** | − 2.66*** | − 735.92*** |

| TMU-SCA | − 0.0007 | 0.3936 | 0.150 | 2.965 | 203.29*** | − 2.16** | − 726.86*** |

| BTC | 0.0024 | 0.0439 | − 2.317 | 27.013 | 17,184*** | − 4.11*** | − 745.76*** |

| ETH | 0.0046 | 0.0602 | − 1.893 | 19.592 | 9109.2*** | − 6.66*** | − 755.66*** |

| BNB | 0.0051 | 0.0699 | − 0.464 | 17.860 | 7316.7*** | − 5.12*** | − 751.94*** |

| ADA | 0.0059 | 0.0684 | − 0.628 | 8.542 | 1705.5*** | − 2.32** | − 745.12*** |

| XRP | 0.0017 | 0.0760 | − 0.194 | 12.506 | 3581.1*** | − 7.96*** | − 672.9*** |

| DOGE | 0.0080 | 0.1129 | 5.616 | 73.429 | 126,227*** | − 9.67*** | − 616.98*** |

| BCH | 0.0004 | 0.0689 | − 1.152 | 16.969 | 6708.5*** | − 4.44*** | − 718.9*** |

| LTC | 0.0013 | 0.0622 | − 1.599 | 12.753 | 3955*** | − 3.11*** | − 729.13*** |

| ETC | 0.0028 | 0.0735 | − 0.265 | 11.824 | 3204.6*** | − 2.02** | − 697.35*** |

| XLM | 0.0026 | 0.0705 | 0.644 | 12.638 | 3691.7*** | − 7.66*** | − 700.06*** |

Note: SD refers to the standard deviation of each asset, JB refers to the Jarque-Bera statistic, DF-GLS represents the Dickey-Fuller test, while PP refers to the Phillips-Perron test. ***, ** and * denote significant at 1%, 5% and 10% level respectively.

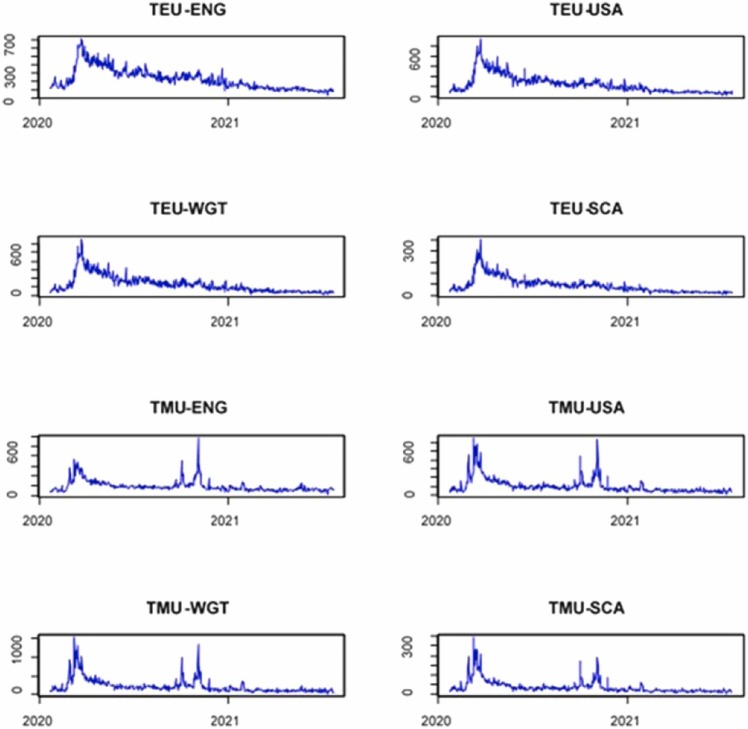

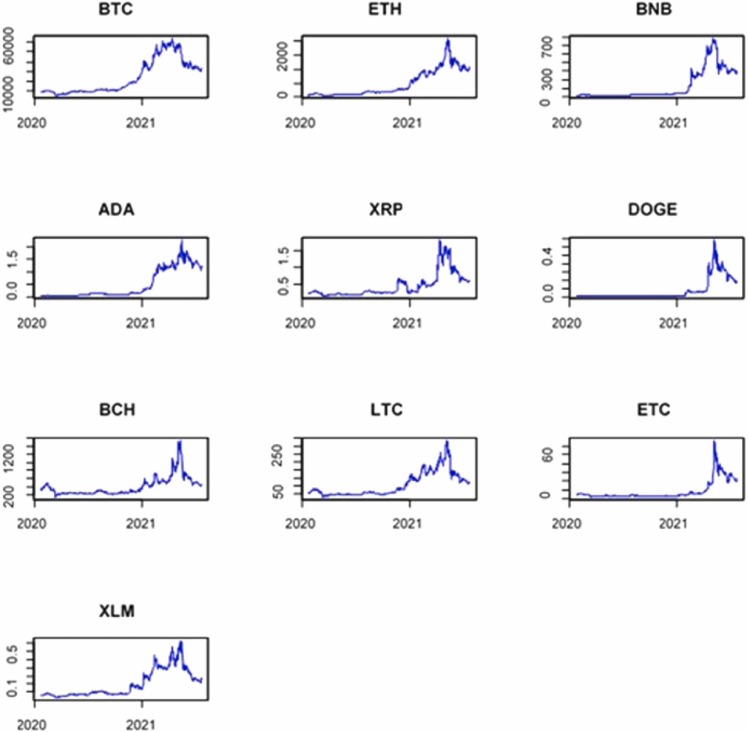

In Fig. 1, we present the time series evolution of the Twitter-derived economic policy uncertainty measures and market uncertainty measures during the COVID-19 period. It can be observed that the largest periods of growth in economic uncertainty appear during March 2020, during the phase when the number of deaths and admitted patients worldwide was growing exponentially. When it comes to market uncertainty measures, they also present very large phases of growth during October and November 2020. Further, Fig. 2 illustrates the time series of the large-cap cryptocurrencies investigated during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is easily discernible that good news about the creation of COVID-19 vaccines has offered a tremendous boost in the market values of cryptocurrencies. This rally began in late 2020 and continued until April 2021.

Fig. 1.

Twitter-derived economic uncertainty measures and market uncertainty measures during the COVID-19 disease. Note: In the above Figure, we present the time series evolution of the Twitter-derived economic policy uncertainty measures and market uncertainty measures during the COVID-19 period.

Fig. 2.

Cryptocurrency market values during the COVID-19 disease. Note: The above Figure illustrates the time series of the large-cap cryptocurrencies investigated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The methodology of Diks and Panchenko (2006) is employed for examining whether non-linear causality in means exists, deriving from Twitter-based uncertainty indices towards the largest-cap cryptocurrencies. We first let a strictly bivariate process (X t), Y t, where X t Granger-causes Y if current values and past values of the X variable have information about the future values of the Y variable that are not contained in Y and Y t. Furthermore, we assume that information sets of past observations of X t and Y t are denoted as F x,t and F y,t. Then X t does not Granger cause Y t when:

| (1) |

Therefore, the null hypothesis of non-linear Granger causality can be defined as:

| (2) |

Under this null hypothesis, Y t+1 is conditionally independent of current and past values of x t, given current and past values of Y t. For finite lags l x and l y, testing the conditional independence can be conducted as:

| (3) |

Before applying the Diks and Panchenko (2006) test for non-linear causal effects in means, the hypothesis of non-linearity should be tested by adopting the BDS test (Broock et al., 1996). If the null hypothesis holds, then the variables examined are identically and independently distributed (i.i.d.) but if the alternative hypothesis holds, then there is linear or non-linear dependency. Moreover, the methodology of Balcilar et al. (2017) is employed for testing non-linear quantile causality in mean and volatility of the cryptocurrencies under scrutiny. This methodology is an extension of the work of Nishiyama et al. (2011) and Jeong et al. (2012) and is beneficial for capturing causality in mean and causality in variance8 . Adopting the non-linear quantile causality specification enables the investigation of the impacts that Twitter-derived economic, or market sentiment exerts on the largest cryptocurrencies under observation, allowing for the estimation as to whether a greater influence is exerted on each digital asset’s mean or volatility. Such a mechanism allows for the thorough investigation of possible paths to improve portfolio performance, particularly as investors are better informed about the drivers of risk and returns on such developing assets. It should be emphasised that the risk-return trade-off could be better estimated not only during normal circumstances but also when extreme upwards (bull) or downwards (bear) movements develop, as lower or upper quantile effects can be studied and hidden non-linear effects can be more accurately discernible.

The variables y t stand for each of the large-cap cryptocurrencies examined and x t represents the TEU-ENG, TEU-USA, TEU-WGT, TEU-SCA, TMU-ENG, TMU-USA, TMU-WGT, or TMU-SCA Twitter-derived sentiment indicators. Let us suppose that Y t−1 ≡ (y t−1, …, y t−p), X t−1 ≡ (x t−1, …, x t−p), Z t = (X t, Y t) and(F yt∣z t−1)(y t, Z t−1) and(F yt∣y t−1)(y t, Y t−1)are functions of the conditional distributions of y t given Z t−1 and Y t−1, respectively.

As with 100% probability. The non-causality hypotheses to be tested are displayed:

| (4) |

| (5) |

The distance measure by Jeong et al. (2012), where J = {s t E(ε t∣Z t−1)f z(Z t−1)} is adopted and denotes the regression error term whereas f z(Z t−1) denotes the marginal density function of Z t−1. In Jeong et al. (2012) the feasible kernel-based sample analogue of J follows this form:

| (6) |

It should be noted that K represents the kernel function with bandwidth h, T shows the sample size, whereas is the estimate of the unknown regression error and is found as:

| (7) |

| (8) |

Notably, constitutes the Nadarya-Watson kernel estimator as below:

| (9) |

And the kernel function is given by L(⋅) whereas the bandwidth is symbolised as h. Additionally, a second-order test is formulated by Balcilar et al. (2017). According to Nishiyama et al. (2011), the detection of higher-order quantile causality can be achieved by testing:

| (10) |

| (11) |

Thereby, x t Granger causes y t in quantile θ up to the moment k by employing eq. (10) for each k. Along the lines of Balcilar et al. (2017), testing is conducted regarding non-parametric Granger causality in the first moment (k=1). In case no rejection of the null hypothesis takes place concerning the first moment still causality may exist in the second moment. This is the reason why Balcilar et al. (2017) argue that tests about the second moment could still be applied. Important prerequisites for safe quantile causality outcomes are defining the appropriate bandwidth h, the lag order p, as well as the Kernel type for K(⋅) and L(⋅). To investigate causality in lower, medium, and upper parts of the distributions a range of seven quantiles have been selected, that is the 0.05, 0.10, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 0.90 and 0.95 quantiles9 . This enables us to derive causality in mean and causality in variance in more detail to effectively estimate the impacts of Twitter-derived economic and market uncertainty on the popular cryptocurrencies under scrutiny.

4. Results

Estimations have been conducted as to whether Twitter-derived economic policy uncertainty measures and market uncertainty measures exert linear Granger effects on the largest cryptocurrencies under observation. Econometric outcomes derived by employing conventional Granger causality estimations are displayed in Table 2. It is revealed that traditional Granger causality tests cannot identify causal interlinkages from uncertainty indices towards the majority of major cryptocurrencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. This phenomenon is even more pronounced in the upper-panel of 2, where market sentiment impacts are examined. It should be underlined that in the examination of Ethereum, Cardano, Ripple, Bitcoin Cash and Litecoin, these assets are identified to be influenced by economic uncertainty as expressed by all tweets in the English language from users outside the US. Somewhat surprisingly, there is evidence that only Ethereum and Binance Coin are influenced by economic uncertainty in the US. The weighted index and the scaled index led to similar findings as only Ethereum, Binance Coin and Bitcoin Cash are receivers of causal effects in either case. In the lower panel of Table 2, linear Granger causality is almost non-existent, as Binance Coin is the only major cryptocurrency receiving Granger effects by Twitter market uncertainty outside of the US. The remaining market uncertainty measures are revealed not to be sources of causal impacts in any examined cryptocurrency.

Table 2.

Linear Granger Causality Tests.

| Panel A: Linear Granger Causality Tests for TEU | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEU-ENG |

TEU-USA |

TEU-WGT |

TEU-SCA |

||||

| Variable | F-stat | Variable | F-stat | Variable | F-stat | Variable | F-stat |

| BTC | 0.972 | BTC | 1.179 | BTC | 1.216 | BTC | 1.402 |

| ETH | 2.550** | ETH | 1.981* | ETH | 2.073* | ETH | 1.838* |

| BNB | 1.606 | BNB | 2.749** | BNB | 3.604*** | BNB | 2.652** |

| ADA | 1.774* | ADA | 1.178 | ADA | 1.018 | ADA | 1.434 |

| XRP | 2.377** | XRP | 0.762 | XRP | 1.174 | XRP | 0.557 |

| DOGE | 0.326 | DOGE | 0.725 | DOGE | 0.996 | DOGE | 0.896 |

| BCH | 2.342** | BCH | 1.620 | BCH | 1.767* | BCH | 1.795* |

| LTC | 2.158** | LTC | 1.361 | LTC | 1.369 | LTC | 1.278 |

| ETC | 1.104 | ETC | 0.875 | ETC | 0.807 | ETC | 0.881 |

| XLM | 0.964 | XLM | 0.977 | XLM | 0.916 | XLM | 1.071 |

| Panel B: Linear Granger Causality Tests for TMU | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMU-ENG |

TMU-USA |

TMU-WGT |

TMU-SCA |

||||

| Variable | F-stat | Variable | F-stat | Variable | F-stat | Variable | F-stat |

| BTC | 0.845 | BTC | 0.602 | BTC | 0.465 | BTC | 0.478 |

| ETH | 0.728 | ETH | 0.375 | ETH | 0.510 | ETH | 0.442 |

| BNB | 2.418** | BNB | 1.203 | BNB | 1.120 | BNB | 1.057 |

| ADA | 1.350 | ADA | 0.856 | ADA | 0.589 | ADA | 0.827 |

| XRP | 0.325 | XRP | 0.367 | XRP | 0.360 | XRP | 0.309 |

| DOGE | 1.235 | DOGE | 1.229 | DOGE | 1.347 | DOGE | 1.064 |

| BCH | 0.979 | BCH | 0.881 | BCH | 0.687 | BCH | 0.874 |

| LTC | 0.947 | LTC | 0.748 | LTC | 0.490 | LTC | 0.640 |

| ETC | 0.563 | ETC | 0.696 | ETC | 0.578 | ETC | 0.570 |

| XLM | 1.054 | XLM | 0.592 | XLM | 0.703 | XLM | 0.564 |

Note: The null hypothesis of non-linear Granger causality can be defined as: is not Granger causing ; where under this stated null hypothesis, Yt+1 is conditionally independent of current and past values of xt, given current and past values of Yt. ***, ** and * denote significant at 1%, 5% and 10% level respectively.

to investigate as to whether the non-linear approach is an appropriate mechanism to detect causality from uncertainty measures to digital currencies, we apply the BDS test (Broock et al., 1996) on the residuals of the returns equation in the Vector Autoregressive (VAR) framework. Results are presented in Table 3 and provide clear evidence that in each variable examined, the null hypothesis of no serial dependence across a range of dimensions is rejected. This indicates that non-linearity exists in a statistically significant manner even at the 99% confidence level.

Table 3.

BDS results.

| Dimension | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| TEU-ENG | 6.50*** | 6.56*** | 5.98*** | 5.77*** |

| TEU-USA | 8.86*** | 10.10*** | 10.17*** | 9.83*** |

| TEU-WGT | 9.45*** | 10.41*** | 10.52*** | 10.32*** |

| TEU-SCA | 8.56*** | 9.69*** | 9.78*** | 9.35*** |

| TMU-ENG | 7.75*** | 7.41*** | 6.87*** | 6.54*** |

| TMU-USA | 6.57*** | 6.71*** | 6.60*** | 6.52*** |

| TMU-WGT | 8.31*** | 7.73*** | 7.27*** | 7.17*** |

| TMU-SCA | 6.33*** | 6.27*** | 5.93*** | 5.47*** |

| BTC | − 5.67*** | − 5.64*** | − 5.76*** | − 5.69*** |

| ETH | 4.00*** | − 4.01*** | − 4.02*** | − 4.05*** |

| BNB | − 3.06*** | − 3.06*** | − 3.08*** | − 3.12*** |

| ADA | − 4.08*** | − 4.11*** | − 4.14*** | − 4.16*** |

| XRP | 3.08*** | 3.09*** | 3.04*** | 3.00*** |

| DOGE | 2.33** | 2.03** | 2.33** | 2.34** |

| BCH | − 5.08*** | − 5.10*** | − 5.11*** | − 5.11*** |

| LTC | − 4.39*** | − 4.53*** | − 4.64*** | − 4.59*** |

| ETC | 6.05*** | 6.02*** | 6.00*** | 6.01*** |

| XLM | − 4.12*** | − 4.13*** | − 4.14*** | − 4.15*** |

Note: The appropriateness of the non-linear approach is tested using the BDS test (Broock et al., 1996) on the residuals of the returns equation in the Vector Autoregressive (VAR) framework. ***, ** and * denote significant at 1%, 5% and 10% level respectively.

The methodology of Diks and Panchenko (2006) is next employed to investigate non-linear causality in means of cryptocurrencies. The econometric outcomes derived are laid out in Table 4. Presented evidence gives credence to the notion that only some of the largest-cap digital currencies are receivers of non-linear Granger causality in mean by Twitter-derived uncertainty measures. To be more precise, it is revealed that Bitcoin, Ethereum, Bitcoin Cash and Litecoin are non-linearly Granger-caused in mean by all four Twitter-derived economic policy uncertainty measures. Moreover, Stellar is influenced only by the non-US index (TEU-ENG) and the scaled index (TEU-SCA). Furthermore, Cardano and Ripple are found to be receivers of Granger causality in mean only at the second dimension (m = 2). These findings reveal that the majority of the most important and well-established digital currencies (Bitcoin, Ethereum, Bitcoin Cash, and Litecoin) react to shocks in Twitter-derived economic policy uncertainty. This documents the existence of tighter linkages between more efficient cryptocurrency markets and modern sentiment indicators in comparison with less established, large cryptocurrency markets. This coincides with the view that as modern financial tools, they share more common characteristics with traditional assets, and constitute part of the overall economic environment to a larger extent.

Table 4.

Nonlinear Granger causality test, Diks and Panchenko (2006).

| TEU-ENG | TEU-USA | TEU-WGT | TEU-SCA | TMU-ENG | TMU-USA | TMU-WGT | TMU-SCA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BTC | m = 2 | 1.694** | 1.423* | 1.263 | 1.637** | − 0.986 | − 0.630 | − 0.447 | − 0.695 |

| m = 3 | 1.792** | 1.559* | 1.336* | 1.463* | − 1.037 | − 0.091 | − 0.173 | − 0.390 | |

| m = 4 | 1.628* | 1.529* | 1.271* | 1.376* | − 0.614 | − 0.443 | − 0.264 | − 0.365 | |

| ETH | m = 2 | 1.559* | 1.728** | 0.604 | 1.151 | 2.169** | 2.103** | 2.020** | 1.919** |

| m = 3 | 1.587* | 1.666** | 1.918** | 1.709** | 2.039** | 1.933** | 1.975** | 1.861** | |

| m = 4 | 1.623* | 1.595* | 1.947** | 1.717** | 1.745** | 1.746** | 1.844** | 1.748** | |

| BNB | m = 2 | 0.802 | 0.639 | 0.626 | 0.754 | 1.130 | 0.943 | 0.946 | 0.878 |

| m = 3 | 0.218 | 0.407 | 0.612 | 0.518 | 1.226 | 0.926 | 0.967 | 0.905 | |

| m = 4 | 0.603 | 0.144 | 0.313 | 0.500 | 1.187 | 0.839 | 0.896 | 0.865 | |

| ADA | m = 2 | 0.733 | 0.900 | 0.910 | 1.305* | 1.795** | 1.343* | 1.408* | 1.157 |

| m = 3 | 0.391 | 0.744 | 0.762 | 0.887 | 1.571* | 1.258* | 1.174 | 0.929 | |

| m = 4 | 0.660 | 0.917 | 0.951 | 0.982 | 1.412* | 0.968 | 1.025 | 1.075 | |

| XRP | m = 2 | 0.835 | 0.795 | 0.955 | 1.230* | 0.677 | 0.237 | 0.263 | 0.319 |

| m = 3 | 0.709 | 0.380 | 0.425 | 0.890 | 1.029 | − 0.013 | 0.021 | 0.114 | |

| m = 4 | 0.194 | − 0.212 | − 0.386 | 0.111 | 0.765 | − 0.172 | − 0.159 | − 0.117 | |

| DOGE | m = 2 | 0.196 | 0.288 | 0.314 | 0.633 | − 0.113 | − 0.863 | − 1.039 | − 0.281 |

| m = 3 | 0.219 | 0.344 | 0.180 | 0.669 | 0.801 | 0.153 | 0.347 | 0.540 | |

| m = 4 | 0.184 | 0.198 | 0.056 | 0.474 | 1.108 | 0.611 | 0.676 | 0.774 | |

| BCH | m = 2 | 2.669*** | 2.609*** | 2.253** | 2.555*** | 2.199** | 1.905** | 1.798** | 1.568* |

| m = 3 | 2.464*** | 2.257** | 1.945** | 2.247** | 2.322*** | 2.000** | 1.780** | 1.782** | |

| m = 4 | 2.258** | 1.761** | 1.691** | 1.904** | 2.370*** | 1.919** | 1.727** | 1.895** | |

| LTC | m = 2 | 2.089** | 1.911** | 2.001** | 2.062** | 1.091 | 0.811 | 1.172 | 0.675 |

| m = 3 | 2.244** | 2.076** | 2.070** | 2.179** | 1.011 | 1.133 | 1.480* | 0.751 | |

| m = 4 | 2.146** | 2.006** | 2.012** | 2.097** | 1.000 | 0.918 | 1.308* | 0.382 | |

| ETC | m = 2 | 1.006 | 0.975 | 0.949 | 1.080 | 1.218 | 1.112 | 1.095 | 1.161 |

| m = 3 | 0.874 | 0.902 | 0.854 | 0.991 | 1.112 | 1.023 | 1.017 | 1.069 | |

| m = 4 | 0.811 | 0.183 | 0.910 | 0.974 | 1.197 | 0.969 | 0.927 | 1.034 | |

| XLM | m = 2 | 0.623 | 0.938 | 0.722 | 1.360* | − 0.552 | − 0.113 | 0.420 | 0.251 |

| m = 3 | 1.630* | 1.155 | 1.012 | 1.533* | 0.030 | 0.878 | 1.244* | 1.174 | |

| m = 4 | 1.565* | 1.101 | 1.209 | 1.526* | 0.490 | 1.015 | 1.295* | 1.238* |

Note: The Diks and Panchenko (2006) methodology is employed for the purpose of investigating non-linear causality in the mean values of our selected cryptocurrencies. ***, ** and * denote significant at 1%, 5% and 10% level respectively. m demonstrates the embedding dimension.

Alternatively, it should be underlined that evidence indicates only Ethereum and Bitcoin Cash are receivers of non-linear effects in mean, no matter which Twitter-based market uncertainty takes place. Outcomes present that the non-US, the US, and the weighted market uncertainty sentiment exert impact upon Cardano in certain dimensions. Additionally, the weighted and the scaled indices are sources of influence upon Stellar (but not in all dimensions examined), and the only weighted index exerts causal impacts on the mean of the Litecoin cryptocurrency (in two dimensions). These results strengthen the view that only the closest substitutes of Bitcoin could prove wealth-generating and be intensely susceptible to market investor sentiment10 .

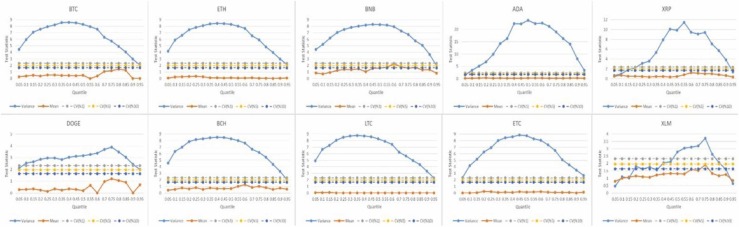

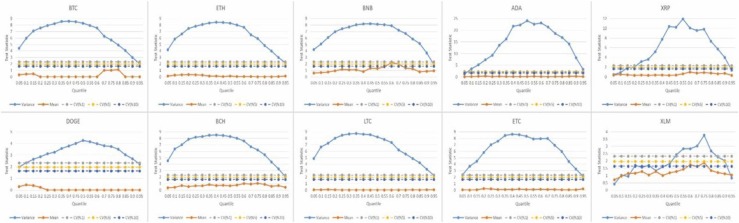

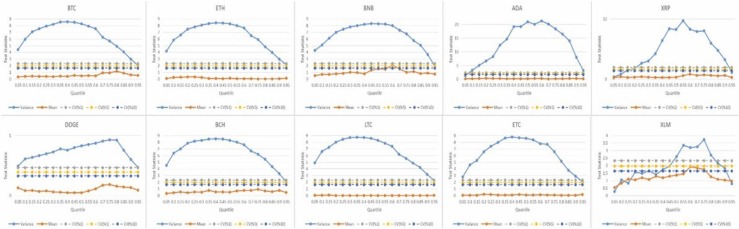

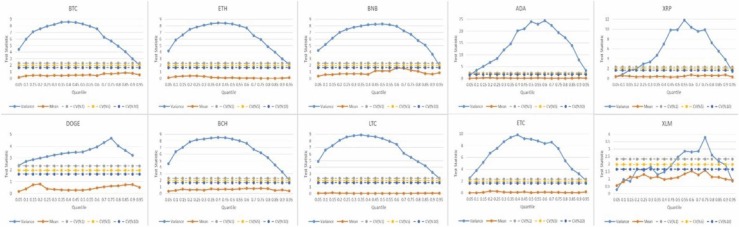

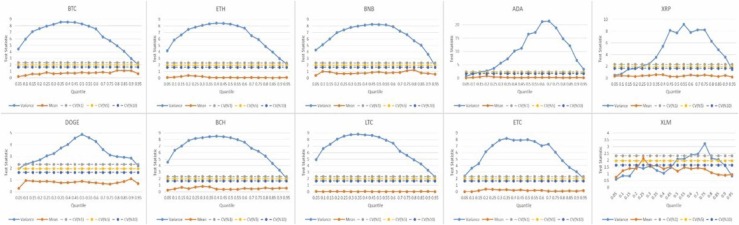

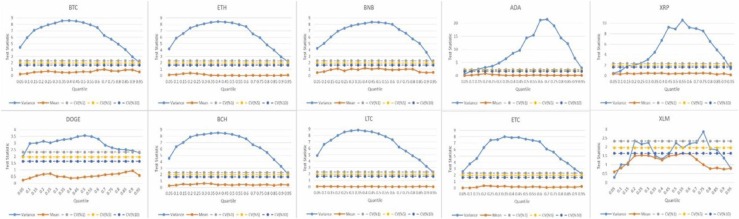

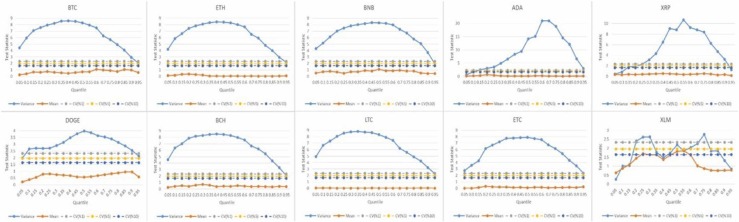

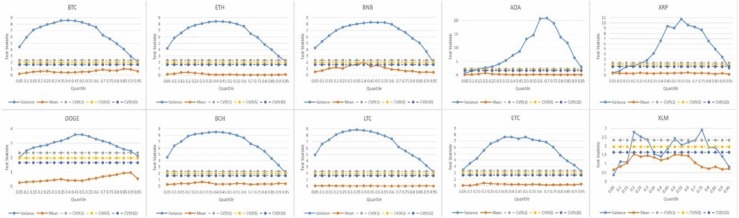

Apart from econometric procedures to trace the non-linear causality in the mean using the methodology of Diks and Panchenko (2006), more advanced estimations are conducted to examine whether non-linear causality in mean as well as in volatility exists. This task has been undertaken by adopting the Balcilar et al. (2017) econometric specification11 Furthermore and for the sake of completeness, we document Galvao’s quantile unit root test at level (Galvao, 2009). The findings are tabulated in Table 5 which suggests that null hypothesis of unit root cannot be rejected at the 5% significance level for almost all the variables and quantiles. Although, quantile unit root test verifies stationarity for variables in first differences and this is in line with the estimations12 of the unit root tests in Table 1. The results of Balcilar et al. (2017) econometric specification are illustrated in Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 through 10. More precisely, in Figures the critical values (CV) at 10%, 5% and 1% level of significance is 1.645, 1.96, and 2.33 respectively. The vertical axis of the graphs depicts the value of quantile causality in mean and in variance (test statistic) whilst the horizontal axis represents the level of quantile distribution (q = 0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20, 0.25, …, 0.80, 0.85, 0.90, 0.95). Findings provide evidence that the Twitter-derived economic and market sentiment indices exert negligible impacts on the means of each of the cryptocurrencies under scrutiny. Notably, this comes in stark contrast with results based on non-linear Granger impacts on volatilities. It is clear from such results, that all of the eight uncertainty measures influence the volatilities of Bitcoin, Ethereum, Binance Coin, Dogecoin, Bitcoin Cash, Litecoin, and Ethereum Classic in a non-linear manner at all quantiles investigated. Nevertheless, it should be noted that volatility in the Cardano market is not affected at the lowest quantile, while Ripple’s volatility does not receive impacts at the two lowest and the upper quantile. Non-linear volatility impacts being present only in middle quantiles is more evident in the case of Stellar were the three lowest, and the upper quantile are revealed to be unaffected by Twitter-based uncertainty during the COVID-19 era. It is worth mentioning that the great majority of statistically significant estimations enjoy high levels of statistical reliability (they are valid at the 99% confidence level). When it comes to estimations of non-linear causality at the upper quantile though most estimations are hardly significant at the 95% confidence level.

Table 5.

Quantile Unit Root test.

| TEU-ENG |

TEU-USA |

TEU-WGT |

TEU-SCA |

TMU-ENG |

TMU-USA |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τ | t-Stat | t-Stat | t-Stat | t-Stat | t-Stat | t-Stat | ||||||

| 0.05 | 0.969 | − 0.206 | 0.971 | − 0.548 | 1.041 | 1.319 | 1.007 | 1.282 | 0.992 | 1.401 | 0.993 | 1.279 |

| 0.10 | 0.991 | − 0.368 | 0.983 | − 1.213 | 1.008 | 0.264 | 1.003 | 1.581 | 0.994 | 1.327 | 0.992 | 1.450 |

| 0.25 | 0.998 | − 0.162 | 0.991 | − 1.693 | 0.988 | 0.786 | 1.000 | 0.169 | 0.997 | 2.285 | 0.995 | 1.886 |

| 0.50 | 0.994 | − 0.730 | 0.996 | − 1.353 | 0.984 | 1.908 | 0.999 | 1.146 | 1.002 | 0.109 | 0.999 | 0.708 |

| 0.75 | 0.982 | − 1.986 | 0.995 | − 1.723 | 0.978 | 1.556 | 0.998 | 1.907 | 1.001 | 0.538 | 1.000 | 0.207 |

| 0.90 | 0.986 | − 0.348 | 1.002 | 0.138 | 0.954 | 1.077 | 0.995 | 1.810 | 1.002 | 1.195 | 1.005 | 1.442 |

| 0.95 | 0.975 | − 0.153 | 1.008 | 0.142 | 0.961 | 1.045 | 0.980 | 1.810 | 1.004 | 1.081 | 1.001 | 1.233 |

| TMU-WGT |

TMU-SCA |

BTC |

ETH |

BNB |

ADA |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τ | t-Stat | t-Stat | t-Stat | t-Stat | t-Stat | t-Stat | ||||||

| 0.05 | 0.992 | 0.094 | 1.013 | 0.371 | 0.972 | 1.241 | 0.999 | 0.011 | 0.971 | 1.128 | 0.994 | 0.184 |

| 0.10 | 0.985 | 0.318 | 1.004 | 0.789 | 1.000 | 0.064 | 0.994 | 0.310 | 0.984 | 0.745 | 0.995 | 0.273 |

| 0.25 | 0.993 | 0.287 | 0.994 | 0.671 | 1.004 | 0.848 | 0.995 | 0.550 | 1.003 | 0.021 | 0.993 | 1.378 |

| 0.50 | 0.969 | 1.882 | 0.993 | 1.319 | 0.996 | 0.013 | 1.001 | 1.086 | 0.995 | 0.400 | 0.997 | 0.434 |

| 0.75 | 0.978 | 1.161 | 0.992 | 1.229 | 0.980 | 2.002 | 1.002 | 1.449 | 0.980 | 2.253 | 1.001 | 0.385 |

| 0.90 | 0.961 | 1.674 | 0.991 | 1.093 | 0.963 | 2.653* | 1.003 | 0.383 | 0.960 | 2.551* | 0.999 | 0.083 |

| 0.95 | 0.936 | 1.371 | 0.990 | 0.459 | 0.931 | 2.752* | 0.991 | 0.874 | 0.961 | 1.094 | 0.998 | 0.028 |

| XRP |

DOGE |

BCH |

LTC |

ETC |

XLM |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τ | t-Stat | t-Stat | t-Stat | t-Stat | t-Stat | t-Stat | ||||||

| 0.05 | 1.009 | 0.641 | 1.035 | 1.441 | 1.074 | 1.216 | 0.979 | 0.318 | 1.005 | 0.788 | 0.942 | 0.976 |

| 0.10 | 1.002 | 0.079 | 1.029 | 2.283 | 1.041 | 1.782 | 0.992 | 0.273 | 1.002 | 0.606 | 0.890 | 1.958 |

| 0.25 | 1.006 | 0.768 | 1.012 | 4.164 | 1.002 | 0.592 | 0.989 | 0.389 | 0.995 | 0.272 | 0.889 | 2.040 |

| 0.50 | 1.000 | 0.264 | 1.009 | 0.696 | 0.995 | 0.211 | 0.991 | 0.285 | 0.993 | 0.669 | 0.900 | 1.951 |

| 0.75 | 0.989 | 1.463 | 0.981 | 3.928* | 0.972 | 2.705 | 1.002 | 0.379 | 0.990 | 1.079 | 0.873 | 2.759* |

| 0.90 | 0.990 | 1.364 | 0.969 | 1.679 | 0.923 | 3.112* | 0.979 | 1.048 | 0.997 | 0.141 | 0.844 | 3.515* |

| 0.95 | 0.978 | 1.077 | 0.945 | 2.078 | 0.894 | 2.533* | 0.978 | 1.078 | 0.992 | 1.002 | 0.842 | 3.668* |

Note: In the above Table, we document Galvao’s quantile unit root test at level (Galvao, 2009). * shows rejection of the null hypothesis at the 5% significance level.

Fig. 3.

Quantile causality-in-mean and in-variance for TEU-ENG. Note: The critical values (CV) at 1%, 5% and 10% level of significance is 2.33. 1.96, and 1.645 respectively.

Fig. 4.

Quantile causality-in-mean and in-variance for TEU-USA. Note: The critical values (CV) at 1%, 5% and 10% level of significance is 2.33. 1.96, and 1.645 respectively.

Fig. 5.

Quantile causality-in-mean and in-variance for TEU-WGT. Note: The critical values (CV) at 1%, 5% and 10% level of significance is 2.33. 1.96, and 1.645 respectively.

Fig. 6.

Quantile causality-in-mean and in-variance for TEU-SCA. Note: The critical values (CV) at 1%, 5% and 10% level of significance is 2.33. 1.96, and 1.645 respectively.

Fig. 7.

Quantile causality-in-mean and in-variance for TMU-ENG. Note: The critical values (CV) at 1%, 5% and 10% level of significance is 2.33. 1.96, and 1.645 respectively.

Fig. 8.

Quantile causality-in-mean and in-variance for TMU-USA. Note: The critical values (CV) at 1%, 5% and 10% level of significance is 2.33. 1.96, and 1.645 respectively.

Fig. 9.

Quantile causality-in-mean and in-variance for TMU-WGT. Note: The critical values (CV) at 1%, 5% and 10% level of significance is 2.33. 1.96, and 1.645 respectively.

Fig. 10.

Quantile causality-in-mean and in-variance for TMU-SCA. Note: The critical values (CV) at 1%, 5% and 10% level of significance is 2.33. 1.96, and 1.645 respectively.

Emphasis should be given on that the three cryptocurrencies not affected by Twitter-derived uncertainty, either emanating from economic conditions or market situations, constitute digital assets with low market values. Arguably, Cardano, Ripple, and Stellar are cryptocurrencies with high levels of volatility and this has allowed investors to speculate by holding and selling them even though their nominal value remains low. A common characteristic of each is the presence of price fluctuation of prices, even when cryptocurrency markets remain somewhat inactive in terms of trading activity. These cryptocurrencies display low sensitivity to economic uncertainty as well as to market uncertainty. This is the reason why they are unaffected by Twitter-related uncertainty measures and remain partially intact as the COVID-19 pandemic develops and persists. These results provide direction for investors, indicating that low-nominally valued cryptocurrencies are not susceptible to extreme movements, during the financial crisis to a larger extent than in normal times.

5. Conclusions

This research investigates non-linear causality in both the mean and volatilities of the largest cryptocurrencies as sourced from Twitter-derived economic and market uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic. Econometric results based upon non-linear (quantile) methodologies are employed to provide a better understanding of the determinants of this novel, popular speculative investments are presented in both normal and identified bull and bear market conditions.

Results suggest that Bitcoin, Ethereum, Bitcoin Cash, and Litecoin are non-linearly influenced in their respective mean by the selected Twitter-derived economic uncertainty indices in a statistically significant manner. On the other hand, only Ethereum, Bitcoin Cash, and partially Cardano are found to be non-linearly caused by Twitter-based market uncertainty measures. When results of non-linear quantile causality are analysed, it is easily discernible that Bitcoin, Ethereum, Binance Coin, Dogecoin, Bitcoin Cash, Litecoin, and Ethereum Classic are receivers of impacts at all quantiles in a statistically reliable manner. It should be underlined though that most digital currencies with low nominal market values (namely Cardano, Ripple, and Stellar) remain unaffected by Twitter-derived sentiment indicators at the lowest or highest quantiles of their volatilities. This result can be partially explained as such low-priced cryptocurrencies quite often present modest levels of volatility, even in times when modest levels of economic uncertainty or investor optimism exist. Such digital currencies are found to be unaffected by volatile investor sentiment or by financial crises.

Such a phenomenon could be very useful for hedging purposes in portfolios that consist of modern or traditional financial assets. Such results find that Twitter-derived sentiment measures are unable to explain the identified volatility in low nominally-priced cryptocurrencies, even in intensely distressed periods such as the COVID-19 pandemic, considered to be a major international financial crisis. Thereby, these cryptocurrencies can serve as safe havens during turbulent economic and market conditions. The alternative methodology indicates that non-linear causality-in-mean exist in digital currencies that present greater resemblances with traditional assets behavioural characteristics. Therefore, it can be concluded that investors willing to hedge their portfolios from the effects of the pandemic would benefit by investing in low nominally-priced, yet highly-capitalised cryptocurrencies. Potential avenues for further research surround further investigation of advanced forms of causal effects exercised by even more sophisticated investor sentiment measures.

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

Such as: “economic, economical, economically, economics, economies, economist, economists, economy” and uncertainty such as: “uncertainty, uncertain, uncertainties, uncertainly”

Such work built on that developed by Corbet et al. (2021) and Umar et al. (2021)

Other relevant pieces include Diniz-Maganini et al. (2021), Goodell and Goutte (2021), Guo et al. (2021), Huang et al. (2021), Corbet et al. (2021) and Shehzad et al. (2021).

It is argued that the nexus of Bitcoin with traditional assets has altered during the pandemic as well as with particular segments while the connection with the US makes the exception (Corbet et al., 2020, Corbet et al., 2020, Corbet et al., 2021). Shehzad et al. (2021) utilise Morlet Wavelet approach and present that gold is preferable to Bitcoin during the pandemic regarding its safe haven abilities (Corbet et al., 2020). It is supported that the Gold/Bitcoin ratio increased in the majority of the Asian, European and US markets investigated.

Available from the www.policyuncertainty.comwebpage

Furthermore, ENG indicates all tweets in the English language from users outside the US,while USA stands for all tweets made in the United States. Additionally, WGT is the weighted index whereas SCA illustrates the scaled index.

Data has been obtained from the Coinmarketcap database

This is one of the key reasons why tracing causality between variables is performed more accurately in comparison with conventional Granger causality methodologies.

Methodological variants, such as building on the work of Galvao (2009), and the use of lower denominations of quantiles were considered, however, for brevity only those stated have been presented. The results of substantial further analysis are available from the authors upon request.

A large number of investors consider that the mature Bitcoin market may have reached its peak and will not be able to display great returns in the future. This is the reason why increased investor attention has focused on the closest substitutes of Bitcoin that could offer credibility but also remain eligible for new bubble creations over time.

It should be underlined that the outcomes extracted about the impacts of TEU-ENG, TEU-USA, TEU-WGT, TEU-SCA, TMU-ENG, TMU-USA, TMU-WGT, and TMU-SCA on the ten largest-cap cryptocurrencies bear large similarities

Detailed results are omitted for brevity of presentation, and are available from the authors upon request.

References

- Akyildirim E., Cepni O., Corbet S., Uddin G. Forecasting mid-price movement of Bitcoin futures using machine learning. Annals of Operations Research. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10479-021-04205-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akyildirim E., Corbet S., Cumming D., Lucey B., Sensoy A. Riding the wave of crypto-exuberance: The potential misusage of corporate blockchain announcements. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2020;159 [Google Scholar]

- Akyildirim E., Corbet S., Lucey B., Sensoy A., Yarovaya L. The relationship between implied volatility and cryptocurrency returns. Finance Research Letters. 2020;33 [Google Scholar]

- Akyildirim E., Corbet S., Sensoy A., Yarovaya L. The impact of blockchain related name changes on corporate performance. Journal of Corporate Finance. 2020;65 [Google Scholar]

- Akyildirim E., Sensoy A., Gulay G., Corbet S., Salari H. Big data analytics, order imbalance and the predictability of stock returns. Journal of Multinational Financial Management. 2021;62 [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., Davis, S., Renault, T. (2021). Twitter-derived measures of economic uncertainty.

- Balcilar M., Bekiros S., Gupta R. The role of news-based uncertainty indices in predicting oil markets: A hybrid non-parametric quantile causality method. Empirical Economics. 2017;53(3):879–889. [Google Scholar]

- Béjaoui A., Mgadmi N., Moussa W., Sadraoui T. A short-and long-term analysis of the nexus between Bitcoin, social media and COVID-19 outbreak. Heliyon. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneki C., Koulis A., Kyriazis N.A., Papadamou S. Investigating volatility transmission and hedging properties between Bitcoin and Ethereum. Research in International Business and Finance. 2019;48:219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Broock W.A., Scheinkman J.A., Dechert W.D., LeBaron B. A test for independence based on the correlation dimension. Econometric Reviews. 1996;15(3):197–235. [Google Scholar]

- Cioroianu I., Corbet S., Larkin C. The differential impact of corporate blockchain-development as conditioned by sentiment and financial desperation. Journal of Corporate Finance. 2021:66. [Google Scholar]

- Conlon T., Corbet S., McGee R.J. Are cryptocurrencies a safe haven for equity markets? An international perspective from the COVID-19 pandemic. Research in International Business and Finance. 2020;54 doi: 10.1016/j.ribaf.2020.101248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbet S., Hou G., Hu Y., Oxley L. We Reddit in a forum: The influence of messaging boards on firm stability. Review of Corporate Finance. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Corbet S., Hou Y., Hu Y., Larkin C., Lucey B., Oxley L. Cryptocurrency liquidity and volatility interrelationships during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finance Research Letters. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2021.102137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbet S., Hou Y., Hu Y., Larkin C., Oxley L. Any port in a storm: Cryptocurrency safe-havens during the COVID-19 pandemic. Economics Letters. 2020:194. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2020.109377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbet S., Hou Y., Hu Y., Lucey B., Oxley L. Aye Corona! The contagion effects of being named Corona during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finance Research Letters. 2021:38. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbet S., Hou Y., Hu Y., Oxley L. The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on asset-price discovery: Testing the case of Chinese informational asymmetry. International Review of Financial Analysis. 2020:72. doi: 10.1016/j.irfa.2020.101560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbet S., Larkin C., Lucey B. The contagion effects of the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from gold and cryptocurrencies. Finance Research Letters. 2020:35. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diks C., Panchenko V. A new statistic and practical guidelines for non-parametric Granger causality testing. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. 2006;30(9-10):1647–1669. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz-Maganini N., Diniz E.H., Rasheed A.A. Bitcoinas price efficiency and safe haven properties during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparison. Research in International Business and Finance. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ribaf.2021.101472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyhrberg A., Foley S., Svec J. How investible is Bitcoin? Analyzing the liquidity and transaction costs of Bitcoin markets. Economics Letters. 2018;171:140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Eross A., McGroarty F., Urquhart A., Wolfe S. The intraday dynamics of Bitcoin. Research in International Business and Finance. 2019;49:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fang T., Su Z., Yin L. Economic fundamentals or investor perceptions? The role of uncertainty in predicting long-term cryptocurrency volatility. International Review of Financial Analysis. 2020;71 [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher E., Larkin C., Corbet S. Countering money laundering and terrorist financing: A case for bitcoin regulation. Research in International Business and Finance. 2021:56. [Google Scholar]

- Fry J. Booms, busts and heavy-tails: The story of Bitcoin and cryptocurrency markets? Economics Letters. 2018;171:225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Galvao A.F., Jr Unit root quantile autoregression testing using covariates. Journal of Econometrics. 2009;152(2):165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gandal N., Hamrick J., Moore T., Vasek M. The rise and fall of cryptocurrency coins and tokens. Decisions in Economics and Finance. 2021;44(2):981–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Goodell J.W., Goutte S. Co-movement of COVID-19 and Bitcoin: Evidence from wavelet coherence analysis. Finance Research Letters. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozgor G., Tiwari A.K., Demir E., Akron S. The relationship between Bitcoin returns and trade policy uncertainty. Finance Research Letters. 2019;29:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Lu F., Wei Y. Capture the contagion network of bitcoin-Evidence from pre and mid COVID-19. Research in International Business and Finance. 2021;58 doi: 10.1016/j.ribaf.2021.101484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Duan K., Mishra T. Is Bitcoin really more than a diversifier? A pre-and post-COVID-19 analysis. Finance Research Letters. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Huynh T.L.D. Does Bitcoin react to Trumpas Tweets? Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance. 2021;31 doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2021.100536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong K., Härdle W.K., Song S. A consistent non-parametric test for causality in quantile. Econometric Theory. 2012;28(4):861–887. [Google Scholar]

- Katsiampa P. Volatility estimation for Bitcoin: A comparison of GARCH models. Economics Letters. 2017;158:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Katsiampa P., Corbet S., Lucey B. High frequency volatility co-movements in cryptocurrency markets. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money. 2019;62:35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Katsiampa P., Corbet S., Lucey B. Volatility spillover effects in leading cryptocurrencies: A BEKK-MGARCH analysis. Finance Research Letters. 2019;29:68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kraaijeveld O., De Smedt J. The predictive power of public Twitter sentiment for forecasting cryptocurrency prices. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money. 2020;65 [Google Scholar]

- Kyriazis N., Papadamou S., Corbet S. A systematic review of the bubble dynamics of cryptocurrency prices. Research in International Business and Finance. 2020;54 [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.D., Li M., Zheng H. Bitcoin: Speculative asset or innovative technology? Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money. 2020;67 [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer S., Xie T., Zhang X. Social media sentiment, model uncertainty, and volatility forecasting. Economic Modelling. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Goodell J.W., Shen D. Comparing search-engine and social-media attentions in finance research: Evidence from cryptocurrencies. International Review of Economics & Finance. 2021;75:723–746. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem M.A., Mbarki I., Shahzad S.J.H. Predictive role of online investor sentiment for cryptocurrency market: Evidence from happiness and fears. International Review of Economics & Finance. 2021;73:496–514. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y., Hitomi K., Kawasaki Y., Jeong K. A consistent nonparametric test for nonlinear causality-Specification in time series regression. Journal of Econometrics. 2011;165(1):112–127. [Google Scholar]

- Papadamou S., Kyriazis N., Tzeremes P., Corbet S. Herding behaviour and price convergence clubs in cryptocurrencies during bull and bear markets. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance. 2021:30. [Google Scholar]

- Philippas D., Rjiba H., Guesmi K., Goutte S. Media attention and Bitcoin prices. Finance Research Letters. 2019;30:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Raheem I.D. COVID-19 pandemic and the safe haven property of Bitcoin. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance. 2021;81:370–375. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkodie S.A., Ahmed M.Y., Owusu P.A. COVID-19 pandemic improves market signals of cryptocurrencies-evidence from Bitcoin, Bitcoin Cash, Ethereum, and Litecoin. Finance Research Letters. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2021.102049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensoy A., Silva T., Corbet S., Tabak B. High-frequency return and volatility spillovers among cryptocurrencies. Applied Economics. 2021;53(37):4310–4328. [Google Scholar]

- Shehzad K., Bilgili F., Zaman U., Kocak E., Kuskaya S. Is gold favourable to bitcoin during the COVID-19 outbreak? Comparative analysis through wavelet approach. Resources Policy. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumasjan A., Braun R., Stolz B. Twitter sentiment as a weak signal in venture capital financing. Journal of Business Venturing. 2021;36(2) [Google Scholar]

- Umar Z., Gubareva M., Yousaf I., Ali S. A tale of company fundamentals vs sentiment driven pricing: The case of GameStop. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance. 2021;30 [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Li X., Shen D., Zhang W. How does economic policy uncertainty affect the Bitcoin market? Research in International Business and Finance. 2020;53 [Google Scholar]

- Wu W., Tiwari A.K., Gozgor G., Leping H. Does economic policy uncertainty affect cryptocurrency markets? Evidence from Twitter-based uncertainty measures. Research in International Business and Finance. 2021 [Google Scholar]