Abstract

Objective

Influenza A, B and C viruses (IAV, IBV and ICV, respectively) circulate globally, infecting humans and causing widespread morbidity and mortality. Here, we investigate the T cell response towards an immunodominant IAV epitope, NP265‐273, and its IBV and ICV homologues, presented by HLA‐A*03:01 molecule expressed in ~ 4% of the global population (~ 300 million people).

Methods

We assessed the magnitude (tetramer staining) and quality of the CD8+ T cell response (intracellular cytokine staining) towards NP265‐IAV and described the T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire used to recognise this immunodominant epitope. We next assessed the immunogenicity of NP265‐IAV homologue peptides from IBV and ICV and the ability of CD8+ T cells to cross‐react towards these homologous peptides. Furthermore, we determined the structures of NP265‐IAV and NP323‐IBV peptides in complex with HLA‐A*03:01 by X‐ray crystallography.

Results

Our study provides a detailed characterisation of the CD8+ T cell response towards NP265‐IAV and its IBV and ICV homologues. The data revealed a diverse repertoire for NP265‐IAV that is associated with superior anti‐viral protection. Evidence of cross‐reactivity between the three different influenza virus strain‐derived epitopes was observed, indicating the discovery of a potential vaccination target that is broad enough to cover all three influenza strains.

Conclusion

We show that while there is a potential to cross‐protect against distinct influenza virus lineages, the T cell response was stronger against the IAV peptide than IBV or ICV, which is an important consideration when choosing targets for future vaccine design.

Keywords: CD8+ T cell, cross‐reactivity, HLA, immune response, immunodominant epitope, Influenza

Influenza A, B and C viruses (IAV, IBV and ICV, respectively) circulate globally, infecting humans and causing widespread morbidity and mortality. Our study provides a detailed characterisation of the CD8+ T cell response towards NP265‐IAV and its IBV and ICV homologues. Evidence of cross‐reactivity between the three different influenza virus strain‐derived epitopes was observed, indicating the discovery of a potential vaccination target that is broad enough to cover all three influenza strains.

Introduction

Influenza viruses cause significant morbidity and mortality, 1 , 2 with an estimated ~650 000 individuals succumbing to infection annually. 3 Individuals who are young, elderly, immunocompromised and pregnant or have other co‐morbidities such as diabetes or asthma are particularly susceptible to severe influenza disease and death. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 The influenza viruses are classified into types A to D. Of these, influenza A virus (IAV) and influenza B virus (IBV) are in constant circulation and the most threatening to human health 3 as they are responsible for annual epidemics. Additionally, IAV has been responsible for 4 global pandemics since 1918. 1 Comparatively, influenza C virus (ICV) typically causes mild infection; however, it can be severe in young children, 8 , 9 and influenza D (IDV) is not yet known to infect humans. 10

Although a vaccine is available against influenza, it typically induces a humoral response, targeting the rapidly mutating haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) surface glycoproteins. 1 , 11 These mutations are predominately responsible for seasonal epidemics and often render previous vaccines ineffective, meaning they must be updated, manufactured and administered annually. Additionally, vaccine effectiveness can vary widely, 10–60%, 12 , 13 and is particularly low in individuals aged over 65 years old (10–35%). 13 Furthermore, vaccines offer limited to no protection in the face of novel reassortments or avian‐derived influenza viruses, which continually pose a threat to human health. As such, there is an urgent need to develop novel and effective therapeutics to combat this deadly disease.

CD8+ T cells are critical in the control and clearance of many viral infections, including influenza virus infections. 14 , 15 , 16 It is well known that memory CD8+ T cells reduce disease severity and symptom scores following influenza virus challenge, 14 , 15 , 16 and CD8+ T cell numbers positively correlate with milder influenza disease. 17 , 18 , 19 Unlike antibodies, CD8+ T cells also recognise internal proteins, such as nucleoprotein (NP), that are typically more conserved than the HA and NA surface glycoproteins, 20 , 21 making CD8+ T cells an attractive target for vaccination. Indeed, there is a lot of interest in the development of CD8+ T cell‐mediated vaccines against influenza. 1 , 22 , 23

There are several factors to consider when thinking about targets for a CD8+ T cell‐mediated vaccine to maximise its protective potential. Firstly, it is important to select human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules expressed at high frequency in the human population. CD8+ T cells recognise viral peptides presented by HLA class I (HLA‐I) molecules on the surface of virally infected cells. 24 HLA molecules are extremely polymorphic, with over 24 000 HLA‐I molecules described to date. 25 Additionally, HLAs are genetically encoded, resulting in distinct expression profiles in different ethnicities and geographical locations. 21 , 26 Secondly, despite being more conserved than surface glycoproteins, internal proteins are subject to mutations that can lead to viral escape. 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 To avoid this, one could target conserved peptides, such as the universal IAV peptides previously described. 21 Thirdly, the response elicited should activate cross‐reactive CD8+ T cells that may offer superior protection against mutations and distinct influenza virus strains. 21 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 CD8+ T cell cross‐reactivity offers an advantage against viral mutation within the same strain of a virus, but also can provide immunity across strains. For example, several studies have shown that T cells specific for seasonal common‐cold causing coronaviruses could provide a level of pre‐existing immunity towards SARS‐CoV‐2, the causative agent of the ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic. 38 , 39 , 40 , 41

The 265ILRGSVAHK273 (NP265‐IAV) peptide derived from IAV was shown to be immunogenic with NP265‐IAV‐specific CD8+ T cells isolated from HLA‐A*03:01+ donors. 42 Subsequently, it was confirmed that NP265‐IAV could be presented and stabilised by the HLA‐A*03:01 molecule. 42 Of note, HLA‐A*03:01 is the 5th most expressed HLA allele in humans, 43 expressed by ~ 4% of the global population, or approximately 300 million individuals worldwide. NP265‐IAV has been classified as a universal IAV peptide, 21 demonstrating 100% conservation within circulating IAV strains, even including those from avian H7N9 viruses. 21 However, despite these features making it an attractive vaccine candidate, the immune response towards this peptide has not been well characterised.

In this study, we investigated the universal NP265‐IAV peptide and characterised the resulting immune response including the T cell receptors (TCR) used by HLA‐A*03:01+ individuals in the recognition of NP265‐IAV. Furthermore, we identified homologues of the NP265‐IAV peptide in both IBV (323VVRPSVASK331, NP323‐IBV) and ICV (270LLKPQITNK278, 270‐ICV). Here, we characterise the CD8+ T cell response towards these peptides and demonstrate that CD8+ T cells expanded against one peptide are capable of cross‐reacting towards the other peptides. We also observed that despite the presence of CD8+ T cells able to recognise each peptide in some donors, the T cell response was stronger against NP265‐IAV peptide. Together, our results provide an in‐depth characterisation of the universal NP265‐IAV peptide and demonstrate the presence of cross‐reactive CD8+ T cells able to recognise NP‐derived homologous peptides from IAV, IBV and ICV. This further highlights the potential for T cells to effectively contribute to vaccines, by eliciting an immune response in a significant proportion of the global population across different types of influenza viruses.

Results

The NP265‐IAV ‐specific CD8 + T cell response has a highly diverse TCR repertoire

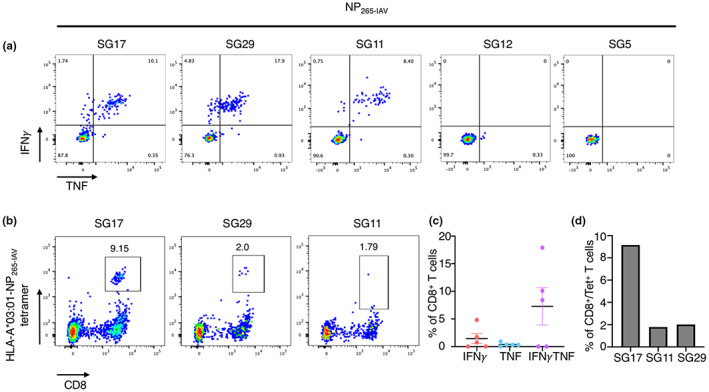

The CD8+ T cell response to HLA‐A*03:01‐restricted NP265‐IAV has been previously reported 21 , 28 , 32 , 42 , 44 , 45 , 46 ; however, data regarding polyfunctionality and TCR repertoire associated with the CD8+ T cell response are limited. The CD8+ T cell response towards NP265‐IAV has been shown to be quite variable between donors, 21 so we firstly wanted to assess the CD8+ T cell response towards this peptide in HLA‐A3+ donors (n = 5, Table 1). CD8+ T cell lines were generated against the NP265‐IAV peptide, and specificity was determined using an intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assay (Figure 1). We observed that the CD8+ T cell response towards NP265‐IAV was variable in our HLA‐A3+ donors, with 3/5 donors producing IFNγ and/or TNF in response to the NP265‐IAV peptide (Figure 1a and c). The majority of NP265‐IAV‐specific CD8+ T cells were able to produce both IFNγ and TNF (double‐positive cells) (Figure 1c). While tetramer staining of our ICS‐positive CD8+ T cell lines confirmed our results, there was no correlation between the strength of the T cell response and the level of tetramer+/CD8+ T cell observed (Figure 1b and d).

Table 1.

HLA‐A locus typing of the donors

| Donor ID | HLA‐A | Age (years) | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|

| SG4 | 03:01, 68:01 | 27 | F |

| SG5 | 03:01, 01:01 | 45 | F |

| SG11 | 03:01, 68:01 | 35 | F |

| SG12 | 03:02, 02:01 | 41 | F |

| SG17 | 03:01, 02:11 | 21 | F |

| SG27 | 03:01, 31:01 | 28 | F |

| SG29 | 03:01, 02:01 | 24 | M |

Figure 1.

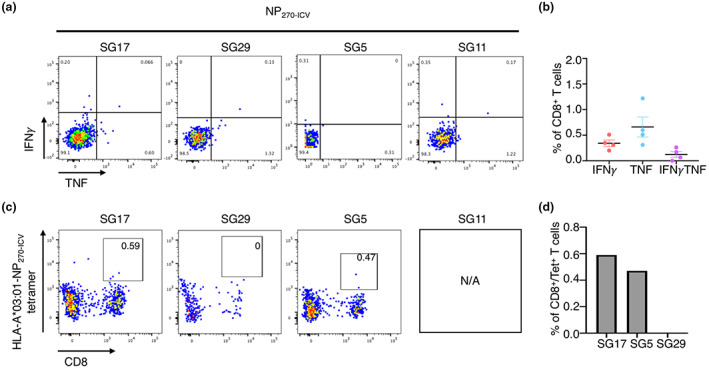

NP265‐IAV peptide can stimulate a CD8+ T cell response in three of our HLA‐A3+ donors. Epitope‐specific CD8+ T cells from HLA‐A3+ donors (n = 5) were expanded in vitro through stimulation with the NP265‐IAV peptide and cultured for 10 days with IL‐2. Peptide specificity was then assessed using an ICS assay or tetramer staining. Samples are gated as per Supplementary figure 1. (a) FACS plots showing IFNγ and TNF production by our five donors in response to the NP265‐IAV peptide. (b) FACS plots showing HLA‐A*03:01‐NP265‐IAV tetramer staining of the n = 3 donors positive by ICS assay. (c) Summary of the proportion of IFNγ+, TNF+, IFNγ/TNF+ production by CD8+ T cells in an ICS assay, minus no‐peptide control. (d) Summary of the proportion of CD8+ Tet+ T cells from each of the donors which had tetramer staining is shown (n = 3).

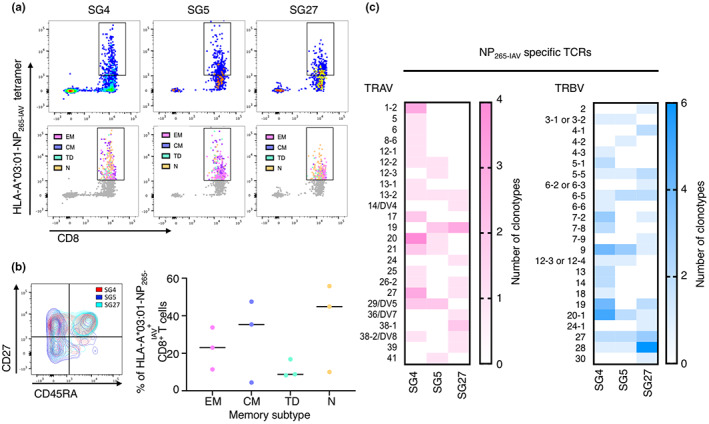

We then determined the phenotypic profile of NP265‐IAV‐specific CD8+ T cells directly ex vivo and assessed the TCR repertoire specific for the NP265‐IAV peptide. We used NP265‐IAV tetramer‐associated magnetic enrichment (TAME) to stain T cells from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from HLA‐A*03:01+ donors (Figure 2a and b). Tetramer‐positive CD8+ T cells were single‐cell sorted, and the TCR repertoire was determined using a reverse transcriptase‐multiplex‐PCR 37 , 47 (Figure 2c, Table 2). A large tetramer+/CD8+ T cell population spanning a large range of mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) was observed in all donors (Figure 2a). Unexpectedly, the majority of tetramer+/CD8+ T cells displayed a CD27+/CD45RA+ phenotype (Figure 2b), typically consistent with naïve cells (average of 36.9 ± 23.9%). Naïve‐like epitope‐specific CD8+ T cells have been observed previously at high proportions in individuals with a poor response to the peptide of interest. 37 , 48 , 49 , 50 For comparison, we performed TAME with a M158‐66 tetramer using PBMCs from an HLA‐A*02:01+ individual and observed that the majority of tetramer+/CD8+ T cells were of central memory phenotype (CD27+/CD45RA−, Supplementary figure 2). By comparison, the remaining NP265‐IAV‐specific CD8+ T cells displayed a memory phenotype consistent with other previously published peptide‐specific CD8+ T cells, 37 , 48 , 49 with 22.7 ± 11.2%, 29.1 ± 22.2%, 11.3 ± 4.8% displaying a effector memory‐like (CD27−/CD45RA−), central memory‐like and terminally differentiated phenotype (CD27−/CD45RA+), respectively (Figure 2b). Although CD8+ T cells from SG5 donor are capable of producing IFNγ and TNF towards the positive control (PMA‐I), no specific IFNγ or TNF production was observed upon NP265‐IAV peptide stimulation, despite the presence of HLA‐A*03:01‐NP265‐IAV tetramer+/CD8+ T cells from SG5 donor's sample, with some cells staining with a high MFI (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Diverse TCR repertoires are utilised for the recognition of NP265‐IAV. PBMCs from HLA‐A*03:01+ donors (n = 3) were tetramer stained individually with a PE‐conjugated NP265‐IAV tetramer. Cells were enriched, surface stained and single‐cell sorted as per the gating strategy in Supplementary figure 1d. The TCRαβ repertoire was determined using single‐cell multiplex RT‐PCR. (a) FACS plots showing NP265‐IAV tetramer staining of CD3+ T cells (top panel) and the phenotype (naïve‐like in orange, effector/effector memory‐like in pink, central memory‐like in purple and terminally differentiated in cyan) of NP265‐IAV tetramer+ cells superimposed on all CD3+ T cells (grey; bottom panel). (b) FACS plot (left panel) and summary (right panel) of the phenotype of NP265‐IAV tetramer+/CD8+ T cells (EM = CD27−/CD45RA−, CM = CD27+/CD45RA−, TD = CD27−/CD45RA+, N = CD27+/CD45RA+). (c) Summary of TRAV and TRBV gene usage by distinct clonotypes in each of three donors for the recognition of NP265‐IAV.

Table 2.

NP265‐IAV‐specific TCR sequences

| TRAV | TRAJ | CDR3Α | Length | TRBV | TRBJ | CDR3β | Length | SG4 | SG5 | SG27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20*01/02/03/04 | 37*02 | CAVQAKRRSSNTGKLIF | 17 | 19*01 | 1–1*01 | CASSIVVVGTEAFF | 14 | 1 | ||

| 38‐2/DV8*01 | 42*01 | CAWENYGGSQGNLIF | 15 | 28*01 | 2–3*01 | CASIPLGSPDPKEDTQYF | 18 | 1 | ||

| 20*01/02/03/04 | 53*01 | CAVLLSRGSNYKLTF | 15 | 12–3*01 or 12–4*01/02 | 2–7*01 | CASSVAIYEQYF | 12 | 1 | ||

| 13–1*01 | 10*01 | CAATSTGGGNKLTF | 14 | 27*01 | 2–1*01 | CASSFGTRRWSHEQFF | 16 | 1 | ||

| 17*01 | 34*01 | CATDAEADKLIF | 12 | 13*01/02 | 2–3*01 | CASTPGGTDTQYF | 13 | 1 | ||

| 25*01 | 20*01 | CAGLSSNDYKLSF | 13 | 9*01 | 1–2*01 | CASSVDLNRDYTF | 13 | 1 | ||

| 8–6*02 | 21*01 | CAVQYNFNKFYF | 12 | 20–1*01/02/03/04/05 | 2–7*01 | CSARTGGYDEQYF | 13 | 1 | ||

| 1–2*01/03 | 29*01 | CARRGNTPLVF | 11 | 14*01/02 | 1–2*01 | CASSQGSNYGYTF | 13 | 1 | ||

| 27*01 | 28*01 | CAGPPGAGSYQLTF | 14 | 20–1*01/02/03/04/05 | 2–3*01 | CSATDRSDLYTQYF | 14 | 1 | ||

| 21*01/02 | 48*01 | CAYLSIGNEKLTF | 13 | 9*01 | 2–2*01 | CASSYRVGELFF | 12 | 1 | ||

| 5*01 | 34*01 | CAERDTDKLIF | 11 | 9*01 | 1–1*01 | CASNSGSTEAFF | 12 | 1 | ||

| 29/DV5*01 | 44*01 | CAARALLIYTGTASKLTF | 18 | 5–1*01/02 | 2–7*01 | CASSLGVGLVVEQYF | 15 | 1 | ||

| 20*01/02/03/04 | 34*01 | CAVQSRYNTDKLIF | 14 | 19*01 | 1–6*01/02 | CASRPDRGNSPLHF | 14 | 1 | ||

| 12–1*01 | 4*01 | CVVTSGGYNKLIF | 13 | 6–5*01 | 2–5*01 | CASTDPVGTQYF | 12 | 1 | ||

| 21*01/02 | 52*01 | CAVKIGNAGGTSYGKLTF | 18 | 7–2*01/02/03/04 | 2–5*01 | CASSLGGVGLVVETQYF | 17 | 1 | ||

| 29/DV5*01 | 52*01 | CAVGPAGGTSYGKLTF | 16 | 5–1*01/02 | 1–1*01 | CASSLRGSNTEAFF | 14 | 1 | ||

| 27*01 | 31*01 | CADQDNARLMF | 11 | 20–1*01/02/03/04/05 | 2–7*01 | CSARDPLANDYEQYF | 15 | 1 | ||

| 27*01 | 28*01 | CAGPPGAGSYQLTF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 17*01 | 8*01 | CATDASFQKLVF | 12 | 1 | ||||||

| 20*01/02/03/04 | 15*01 | CAVQAQGGTALIF | 13 | 1 | ||||||

| 12–2*01/02/03 | 10*01 | CAVNTGGGNKLTF | 13 | 1 | ||||||

| 6*01/02/05/07 | 42*01 | CALYGGSQGNLIF | 13 | 1 | ||||||

| 13–2*01/02 | 9*01 | CAVVTGGFKTIF | 12 | 1 | ||||||

| 1–2*01/03 | 16*02 | CAVVSDGQKLLF | 12 | 1 | ||||||

| 26–2*01 | 54*01 | CILRGPSIQGAQKLVF | 16 | 1 | ||||||

| 1–2*01/03 | 43*01 | CAVHPGYNNNDMRF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 20–1*01/02/03/04/05 | 2–7*01 | CSARDPGLAGGNSYEQYF | 18 | 1 | ||||||

| 13*01/02 | 2–1*01 | CASSSGLAGSGNEQFF | 16 | 1 | ||||||

| 18*01 | 2–3*01 | CASSPGLAGLSTDTQYF | 17 | 1 | ||||||

| 19*01 | 2–2*01 | CASCKYMTGTGELFF | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| 14*01/02 | 2–7*01 | CASSQWDWGEQYF | 13 | 1 | ||||||

| 6–6*01/03 | 1–3*01 | CASSYSLSVHSGNTIYF | 17 | 1 | ||||||

| 9*01 | 2–7*01 | CASSVGVEVYEQYF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 7–2*01/04 | 1–2*01 | CASSFSWGDVYGYTF | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| 7–8*01/03 | 1–2*01 | CASSSSRQGGYGYTF | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| 5–5*01/02/03 | 1–2*01 | CASSLDLNYGYTF | 13 | 2 | ||||||

| 7–2*02/0 | 2–1*01 | CASSPGVSNEQFF | 13 | 1 | ||||||

| 27*01 | 2–7*01 | CASSQPGLAGPHEQYF | 16 | 1 | ||||||

| 3–1*01/02 or 3–2*01/02/03 | 1–6*02 | CASSPHGGQTFNSPLHF | 17 | 1 | ||||||

| 20–1*01/02/03/04/05 | 1–6*02 | CSARLGGNLGSPLHF | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| 19*01 | 1–1*01 | CASSPPYREYTEAFF | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| 4–3*01/02/03/04 | 1–2*01 | CASSQEGGYYGYTF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 7–8*01/03 | 1–5*01 | CASSQSTGLSNQPQHF | 16 | 1 | ||||||

| 29/DV5*01 | 26*01 | CAASAKNYGQNFVF | 14 | 9*01/02/03 | 2–5*01 | CASXXSGGGAETQYF | 15 | 5 | ||

| 12–2*01/02/03 | 13*02 | CAVNQGYQKVTF | 12 | 20–1*01/02/03/04/05 | 1–6*01 | CSAPGGPLDYNSPLHF | 16 | 1 | ||

| 13–2*01/02 | 26*01 | CAEAVNFVF | 9 | 5–5*01/02/03 | 2–7*01 | CASSLDVGSEQYF | 13 | 1 | ||

| 19*01 | 23*01 | CALSDLYNQGGKLIF | 15 | 12–3*01 or 12–4*01/02 | 2–1*01 | CASSLVLAGVEQFF | 14 | 1 | ||

| 41*01 | 45*01 | CAVRGGGGADGLTF | 14 | 3–1*01/02 or 3–2*01/02/03 | 1–2*01 | CASSPPTSNYGYTF | 14 | 1 | ||

| 20*01/02/03/04 | 16*01 | CAVRSDGQKLLF | 12 | 9*01 | 2–5*01 | CASSPRLSGGGQETQYF | 17 | 1 | ||

| 21*01/02 | 50*01 | CAVRLTSYDKVIF | 13 | 27*01 | 1–6*01 | CASSRINSPLHF | 12 | 1 | ||

| 19*01 | 22*01 | CALSEALRGSARQLTF | 16 | 1 | ||||||

| 29/DV5*01 | 26*01 | CAAXXKXYGQNFVF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 12–3*01/02 | 33*01 | CAMSAPEEGNYQLIW | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| 28*01 | 2–5*01 | CASSLLAFQETQYF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 6–5*01 | 2–1*01 | CASSYGGGEQFF | 12 | 1 | ||||||

| 4–2*01/02 | 1–2*01 | CASSQAAGRDGYTF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 9*01/02/03 | 2–5*01 | CASXXSGGGAETQYF | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| 20–1*01/02/03/04/05 | 2–1*01 | CSAGGGPRIYNEQFF | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| 27*01 | 1–6*01 | CASSRINSPLHF | 12 | 1 | ||||||

| 6–5*01 | 2–7*01 | CASSVGTGKYEQYF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 26–2*01 | 41*01 | CILRLQNSNSGYALNF | 16 | 27*01 | 1–1*01 | CASSIAVNTEAFF | 13 | 1 | ||

| 19*01 | 54*01 | CALSDPQGAQKLVF | 14 | 4–1*01/02 | 2–1*01 | CASSQERSSYNEQFF | 15 | 1 | ||

| 14/DV4*03 | 33*01 | CAMRVRTDSNYQLIW | 15 | 19*01/02/03 | 1–4*01 | CATSTGGKATNEKLFF | 16 | 1 | ||

| 19*01 | 54*01 | CALSGLIQGAQKLVF | 15 | 24–1*01/02 | 2–7*01 | CATSDSRGGSGLAYEQYF | 18 | 1 | ||

| 27*01 | 12*01 | CAGDPLVDSSYKLIF | 15 | 28*01 | 1–5*01 | CASSFPKGYSNQPQHF | 16 | 1 | ||

| 24*01 | 37*02 | CAFGSSNTGKLIF | 13 | 4–1*01/02 | 2–1*01 | CASSQGERGDWNEQFF | 16 | 1 | ||

| 38–1*01/02/03/04 | 40*01 | CAFMKQAYKYIF | 12 | 20–1*01/02/03/04/05 | 2–3*01 | CSARDRTSGSTDTQYF | 16 | 1 | ||

| 36/DV7*04 | 31*01 | CASLLNNARLMF | 12 | 19*01 | 1–1*01 | CASTGGTEAFF | 11 | 1 | ||

| 38‐2/DV8*01 | 33*01 | CSLDSNYQLIW | 11 | 28*01 | 1–1*01 | CASSFLAVQGDTEAFF | 16 | 1 | ||

| 13–2*01/02 | 42*01 | CAESGYGGSQGNLIF | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| 39*01 | 49*01 | CAVDYTGNQFYF | 12 | 1 | ||||||

| 19*01 | 40*01 | CAXSEGTXKYIF | 12 | 1 | ||||||

| 38–1*01/02/03/04 | 34*01 | CAFTHYNTDKLIF | 13 | 1 | ||||||

| 28*01 | 2–7*01 | CASSPIAGGYEQYF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 30*01/05 | 2–5*01 | CAWSGGEGSEETQYF | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| 27*01 | 2–1*01 | CASSLSSSGRALFF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 7–9*01/03 | 2–3*01 | CASSSPGQGTDTQYF | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| 7–2*01/02/03/04 | 2–1*01 | CASSVPGQGIPNNEQFF | 17 | 1 | ||||||

| 28*01 | 1–5*01 | CASSPTGGNQPQHF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 28*01 | 2–7*01 | CASSSRLAGGSYEQYF | 16 | 1 | ||||||

| 6–2*01 or 6–3*01 | 1–6*01/02 | CASSYPGPDKGNSPLHF | 17 | 1 | ||||||

| 9*01 | 1–1*01 | CASGQTNTEAFF | 12 | 1 | ||||||

| 2*01/02/03 | 1–5*01 | CASSVPRGEDNQPQHF | 16 | 1 | ||||||

| 28*01 | 2–7*01 | CASFDGGDYEQYF | 13 | 1 | ||||||

| 5–5*01/02/03 | 1–5*01 | CASSPDINQPQHF | 13 | 1 | ||||||

| 6–5*01 | 2–1*01 | CASSSSSTHNEQFF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 6–5*01 | 2–7*01 | CATAGGLEQYF | 11 | 1 | ||||||

| 5–5*01/02/03 | 2–3*01 | CASSLGVGGDTQYF | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| 27*01 | 2–3*01 | CASSFLGRDTDTQYF | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| Total number of sequences | 44 | 21 | 29 | |||||||

TRAV represents the variable α‐chain gene usage; TRBV represents the β‐chain gene usage. X refers to an unidentified amino acid. Numbers represent how many times that distinct clonotype was observed in each donor.

TCR, T cell receptor.

To our knowledge, there is only a single report of an NP265‐IAV‐specific TCR repertoire. 46 The NP265‐IAV‐specific TCR repertoire was determined using TAME on human lung tissue from a single donor and was very diverse, with only a few clonotypes observed at a higher frequency than the others. 46 Similarly, our analysis showed that the TCR repertoire utilised in the recognition of NP265‐IAV was diverse in all three donors, with only a single clonotype observed more than once in donors SG4 and SG5 (Table 2), resulting in a high Simpsons diversity index of 0.9989, 0.9523 and 1.0000 in donors SG4, SG5 and SG27, respectively. The TCR repertoire was also entirely private, with no shared clonotypes between individuals (Table 2). Some TRAV and TRBV gene usage biases were observed across the distinct clonotypes (Figure 2c); however, these were predominately different between individuals. Shared TRAV19 biases were observed for SG5 (20%) and SG27 (23%), and shared TRBV9 and TRBV20‐1 biases were seen in SG4 (12% and 14%, respectively) and SG5 (21% and 14%, respectively) (Figure 2c). A shared TRBV27 bias was also observed in SG5 (14%) and SG27 (12%) (Figure 2c). Interestingly, these were different to the TRAV25 and TRBV14/DV4 biases observed by Pizzolla et al. 46 further highlighting the diversity and private nature of the NP265‐IAV‐specific CD8+ TCR repertoire. The TCR repertoire showed a preferred CDR3α length of 12 (~23 ± 6%), 14 (19 ± 11%) or 15 (19 ± 12%) amino acids and a CDR3β length of 14 (24 ± 10%), 15 (19 ± 3%) or 16 (16 ± 11%) residues across the distinct clonotypes (Supplementary figure 3a). These CDR3 loops are slightly longer than those reported for other immunodominant IAV epitopes such as HLA‐B*37:01‐restricted NP338 peptide, 37 the HLA‐A*02:01‐restricted M158 peptide, 28 and the HLA‐B*35:01‐restricted NP418 peptide. 28 However, no obvious CDR3 motifs were observed within these preferred lengths (Supplementary figure 3b).

Overall, we have shown that the NP265‐IAV peptide induces variable CD8+ T cell responses in our cohort of HLA‐A*03:01+ donors, and ex vivo analysis revealed that a high proportion of NP265‐IAV‐specific CD8+ T cells display a naïve like phenotype and utilise a private and highly diverse TCR repertoire for the recognition of the NP265‐IAV peptide.

NP265‐IAV homologous peptides are present in IBV and ICV

The NP265‐IAV peptide was described in 2013 as a universal epitope due to its high conservation among influenza A virus strains, including the then‐emerging avian H7N9 virus. 21 To assess the conservation of the NP265‐IAV peptide and determine whether it is still highly conserved, we aligned 4328 strains of IAV and assessed the conservation within the NP265‐IAV peptide. We found that the NP265‐IAV peptide is still highly conserved, displaying 98% conservation within our 4328 isolates 51 (Table 3). Interestingly, it has been published that the NP265‐IAV peptide most frequently has an isoleucine at position 1 (P1) and rarely a Valine at P1, even though both are immunogenic epitopes. 32 Given the high conservation of the NP265‐IAV peptide, we wondered if this peptide could also be conserved across different influenza virus types. Therefore, we aligned the NP sequences from a representative strain of influenza A, B and C virus. The IAV‐NP protein is 34.5% identical in protein sequence with IBV‐NP and 19.0% identical with ICV‐NP. NP265‐IAV peptide homologues were identified in both IBV with the NP323‐IBV peptide (323VVRPSVASK331) and ICV with the NP270‐ICV peptide (270LLKPQITNK278). The three peptides all shared canonical anchor residues characteristic of the HLA‐A*03:01 molecule, with a hydrophobic residue at position 2 (P2‐V/L) and a C‐terminal lysine (PΩ‐K). 42 , 52 The conservation of these residues indicated that all three peptides might be able to bind to the HLA‐A*03:01 molecule and potentially activate CD8+ T cells. The NP265‐IAV and NP323‐IBV shared five identical residues (55% identity and 78% similarity) and only two identical residues with NP270‐ICV (22% identity and 78% similarity).

Table 3.

Sequence conservation of NP265‐IAV and its IBV and ICV homologues

| Influenza A | Influenza B | Influenza C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | ILRGSVAHK | VVRPSVASK | LLKPQITNK |

| No. of Unique Seq | 4328 | 1710 | 66 |

| % Conservation of Unique Seq | 98.24% | 98.13% | 100.00% |

IBV, Influenza B virus; ICV, Influenza C virus.

To confirm that our selected virus strains and identified homologous peptides were representative, we determined the conservation of these peptides within circulating viruses IBV and ICV strains from the Influenza Research Database. 51 We found that the NP323‐IBV peptide was 98.1% conserved between 1710 unique IBV‐NP sequences, and NP270‐ICV was determined to be 100% conserved in all 66 unique ICV‐NP sequences (Table 3), demonstrating that they are universally conserved within their influenza virus type.

IBV and ICV‐derived NP265‐IAV homologous peptides can stabilise HLA‐A*03:01 but are less immunogenic than IAV‐derived one

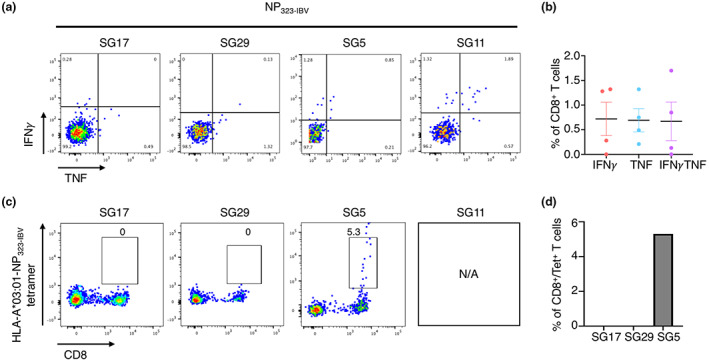

Firstly, we wanted to assess the stability of NP265‐IAV in complex with HLA‐A*03:01 and whether these IBV‐ and ICV‐derived homologous could also stabilise the HLA‐A*03:01 molecule, which would suggest that they can be presented by HLA‐A*03:01 at the cell surface for CD8+ T cell recognition. To do this, we refolded HLA‐A*03:01 with each of the homologous peptides and assessed their stability using Differential Scanning Fluorimetry. All three peptides stabilised the HLA‐A*03:01 molecule; however, NP265‐IAV and NP323‐IBV both showed a ~ 7°C higher melting point (Tm) than NP270‐ICV (53.9°C and 53.3°C, respectively, versus 46.9°C) (Table 4). Since all three homologous peptides can bind and stabilise the HLA‐A*03:01 molecule, we sought to determine whether NP323‐IBV and NP270‐ICV could activate CD8+ T cells. To this end, we generated NP323‐IBV‐ and NP270‐ICV‐specific CD8+ T cell lines and assessed their specificity using an intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assay (Figures 3 and 4, respectively). Interestingly, we found that NP323‐IBV was immunogenic in two out of four donors (Figure 3a and b), whereas the NP270‐ICV generated minimal CD8+ T cell specificity (Figure 4a and b). The specificity of the CD8+ T cells towards NP323‐IBV was further confirmed using HLA‐A*03:01‐NP323‐IBV tetramers on the remaining NP323‐IBV‐specific CD8+ T cell lines (Figure 3c and d). Similarly, using NP270‐ICV tetramer, we observed a small proportion of tetramer+/CD8+ T cells (Figure 4c and d) in line with the minimal CD8+ T cell response observed upon NP270‐ICV stimulation (Figure 4a and b).

Table 4.

Thermal stability of peptide‐HLA complexes

| pHLA‐A*03:01 complex | Tm (°C) ± sem |

|---|---|

| NP265‐IAV (ILRGSVAHK) | 53.9 ± 0.1 (n = 2) |

| NP323‐IBV (VVRPSVASK) | 53.3 ± 0.3 (n = 2) |

| NP270‐ICV (LLKPQITNK) | 46.9 ± 0.1 (n = 2) |

Tm, thermal midpoint temperature.

Figure 3.

Select HLA‐A*03:01+ individuals have a response to the NP323‐IBV peptide. Peptide‐specific CD8+ T cells from HLA‐A*03:01+ donors (n = 4) were expanded in vitro through stimulation with the NP323‐IBV peptide and cultured for 10 days with IL‐2. Specificity was assessed using an ICS assay or tetramer staining. Samples are gated as per Supplementary figure 1. (a) FACS plots showing IFNγ and TNF production (n = 4) in response to the NP323‐IBV peptide. (b) Summary of the proportion of IFNγ+, TNF+ and IFNγ/TNF+ production by CD8+ T cells in response to the NP323‐IBV peptide, minus the no‐peptide control. (c) FACS plots showing NP323‐IBV tetramer staining (n = 3 donors). (d) Summary of the proportion of CD8+Tet+ T cells (n = 3).

Figure 4.

NP270‐ICV elicits weak CD8+ T cell response in select HLA‐A*03:01+ donors. Peptide‐specific CD8+ T cells from HLA‐A*03:01+ donors (n = 4) were expanded in vitro through stimulation with the NP270‐ICV peptide and cultured for 10 days with IL‐2. Specificity was assessed using an ICS assay or tetramer staining. Samples are gated as per Supplementary figure 1. (a) FACS plots showing IFNγ and TNF production (n = 4) in response to the NP270‐ICV peptide. (b) Summary of the proportion of IFNγ+, TNF+ and IFNγ/TNF+ production by CD8+ T cells in response to the NP323‐IBV peptide, minus the no‐peptide control. (c) FACS plots showing NP270‐ICV tetramer staining (n = 3 donors). (d) Summary of the proportion of CD8+Tet+ T cells (n = 3).

Altogether, these data show that NP323‐IBV and NP270‐ICV represent novel immunogenic epitopes eliciting CD8+ T cell recognition and activation, albeit with a lower proportion of CD8+ T cells responding to NP323‐IBV and NP270‐ICV than NP265‐IAV.

CD8 + T cells are cross‐reactive between NP‐derived epitopes from multiple influenza virus types

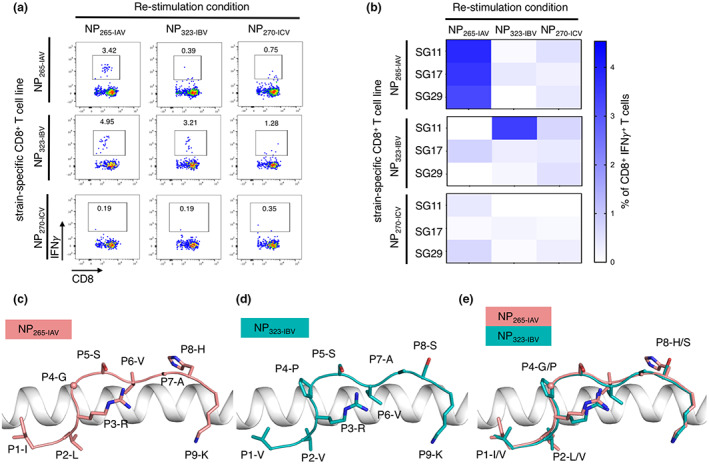

Due to the sequence homology between the immunogenic NP265‐IAV, NP323‐IBV and NP270‐ICV peptides, we next wanted to assess whether CD8+ T cells could cross‐recognise all three peptides presented by HLA‐A*03:01. CD8+ T cells were expanded against each of the three peptides individually, and specificity towards each peptide was assessed in an ICS assay (Figure 5). CD8+ T cells produced variable IFNγ and TNF in responses towards their cognate peptide with some level of cross‐reactivity towards the other peptides (Figure 5a). CD8+ T cell lines expanded against NP265‐IAV generated the greatest IFNγ and TNF response towards the cognate peptide (2–3%), with some low level of cross‐reactivity towards the NP323‐IBV (0.3–0.6%) and NP270‐ICV (0.5–0.7%) peptides (Figure 5b). CD8+ T cell lines expanded against NP323‐IBV demonstrated greater variability towards the cognate NP323‐IBV peptide (0–4.5%) (Figure 5b). Conversely, minimal CD8+ T cell responses towards the three peptides were observed when CD8+ T cell lines were generated against the NP270‐ICV peptide (Figure 5b).

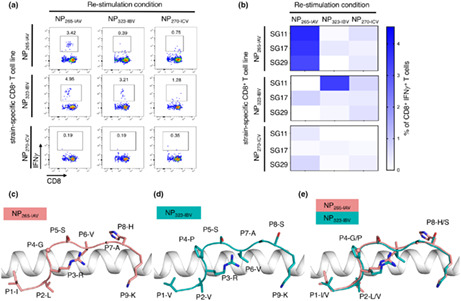

Figure 5.

Cross‐reactivity of CD8+ T cells towards the three NP peptides and similar presentation of NP265‐IAV and NP323‐IBV peptides by HLA‐A*03:01 molecule. Peptide‐specific CD8+ T cells from HLA‐A*03:01 donors (n = 3) were expanded in vitro through stimulation with one of NP265‐IAV, NP323‐IBV or NP270‐ICV peptides and cultured for 10 days with IL‐2. Specificity and cross‐reactivity were assessed by stimulating CD8+ T cell lines with each of the homologous peptides separately in an ICS assay. (a) Representative FACS plots of IFNγ+ and TNF+ production in the ICS assay. (b) Summary heatmap representing IFNγ+ production by CD8+ T cells, minus the no‐peptide control, in the ICS assay. (c) HLA‐A*03:01 (white ribbon) binding to NP265‐IAV (stick) coloured in salmon. (d) HLA‐A*03:01 (white ribbon) binding to NP323‐IBV (stick) coloured in teal. (e) Overlay of NP265‐IAV (salmon) and NP323‐IBV (teal) presented by HLA‐A*03:01 (white ribbon) with the differences in peptide sequence represented as sticks and the shared residues in the drawing below.

Overall, here we demonstrate that CD8+ T cell responses are typically strongest against their cognate peptide; however, some level of cross‐reactivity can be observed.

NP265‐IAV and NP323‐IBV epitopes are presented in a similar conformation

To further understand the difference in stability and potentially immunogenicity, we aimed to solve the structure of each of the three peptides in complex with the HLA‐A*03:01 molecule using X‐ray crystallography (Table 5). We successfully solved the crystal structures for NP265‐IAV and NP323‐IBV in complex with HLA‐A*03:01 with a well‐defined electron density for the peptides but could not crystallise HLA‐A*03:01‐NP270‐ICV (Supplementary figure 4). The NP265‐IAV peptide adopted a canonical conformation within the cleft of HLA‐A*03:01 anchored by P2‐Leu and P9‐Lys (Figure 5c), as well as secondary anchor P3‐Arg that forms a salt bridge with Glu152 (Supplementary figure 5a). The P9‐Lys is buried deep in the F pocket of HLA‐A*03:01 interacting via a salt bridge with the Asp116 and with a hydrophobic patch formed by Leu81, Ile95 and Ile97 (Supplementary figure 5b). The exposed surface of the NP265‐IAV is relatively flat and hydrophobic, with small residues such as the P4‐Gly, P5‐Ser, P6‐Val and P7‐Ala, with the only large and exposed residue being the P8‐His (Figure 5c). Interestingly, this lack of featured side chains, and a rather flat conformation of the peptide, is similar to one observed for HLA‐A*02:01‐restricted influenza A virus M158‐66 peptide. 24 , 53 Superimposition of the HLA‐A*03:01‐NP265‐IAV and HLA‐A*02:01‐M158‐66 structures reveals a similarly flat and central conformation of the peptide backbone, favored by a shared P4‐Gly residue that introduces a kink at the start of the central region of the peptides (Supplementary figure 5c).

Table 5.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| HLA‐A*03:01‐NP265‐IAV | HLA‐A*03:01‐NP323‐IBV | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection statistics | ||

| Space group | P 63 2 2 | P 6 2 2 |

| Cell dimensions (a, b, c) (Å) | 155.57, 155.59, 170.76 | 155.26, 155.26, 85.33 |

| Resolution (Å) |

48.82–1.95 (1.98–1.95) |

44.82–2.20 (2.27–2.20) |

| Total number of observations | 2 027 076 (104 909) | 1 259 531 (108 430) |

| Number of unique observations | 88 833 (4468) | 31 267 (2662) |

| Multiplicity | 22.8 (23.5) | 40.3 (40.7) |

| Data completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) |

|

I/σI |

13.5 (2.2) |

16.5 (2.5) |

| Mn(I) half‐set correlation CC(1/2) | 0.998(0.781) | 0.987(0.916) |

| R pim a (%) | 4.8 (49.1) | 4.4 (55.0) |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Non‐hydrogen atoms | ||

| Protein | 6412 | 3202 |

| Water | 1060 | 301 |

| Rfactor b (%) | 19.3 | 21.7 |

| R free b (%) | 22.4 | 26.6 |

| Rms deviations from ideality | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.04 | 1.10 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||

| Allowed region | 97.6 | 95.0 |

| Generously allowed region | 2.2 | 5.0 |

| Disallowed region | 0.2 | 0 |

R p.i.m = Σhkl [1/(N−1)]1/2 Σi ¦ Ihkl,i− < Ihkl > ¦ / Σhkl < Ihkl >.

R factor = Σhkl ¦ ¦ F o ¦ − ¦ F c ¦ ¦ / Σhkl ¦ F o ¦ for all data except ≈ 5%, which were used for R free calculation.

The NP323‐IBV peptide differs from the NP265‐IAV peptide at four positions (Figure 5d), namely P1 (Val to Ile), P2 (Val to Leu), P4 (Pro to Gly) and P8 (Ser to His). The anchor residues P3 and P9 are identical for both peptides (Figure 5c and d), but P2‐Val (NP323‐IBV) has a shorter side chain anchoring into the B pocket. Additionally, P4‐Pro creates a more constrained kink than P4‐Gly. Despite this, superimposition of the HLA‐A*03:01 structures presenting the NP265‐IAV and NP323‐IBV show that both peptides adopt similar conformation, reinforcing their potential to be recognised by cross‐reactive CD8+ T cells. Minimal differences between the structures reveal a root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) of 0.18 Å for the HLA α1‐α2 domains and of 0.37 Å for the peptides (Figure 5e). Like the NP265‐IAV peptide, the NP323‐IBV peptide has a rather featureless conformation, comparable to M158‐66 peptide as well (Supplementary figure 5d), and its P8 residue facing the solvent, is a smaller P8‐Ser instead of a P8‐His residue (Figure 5d). This suggests that the NP323‐IBV is more featureless than the NP265‐IAV peptide, and this might impact even further on TCR recognition and could explain the lower immunogenicity of NP323‐IBV than NP265‐IAV (Figure 3).

Overall, the two pHLA complex structures show that the NP265‐IAV and NP323‐IBV peptides were presented in a similar fashion by HLA‐A*03:01. The structural similarity is likely to contribute to the cross‐reactive potential of the CD8+ T cell observed, as well as been favored by a diverse TCR repertoire.

Discussion

Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells play an important role in anti‐viral immunity by limiting viral replication and clearing infected cells that display viral peptides presented by HLA molecules at the cell surface. 14 , 15 , 16 Since influenza viruses are constantly mutating, CD8+ T cells that recognise highly conserved peptides, such as NP265‐IAV, can ensure the recognition of distinct virus strains. Therefore, it is important to understand and identify these conserved epitopes and their associated immune responses, as they may be of interest in the generation of future CD8+ T cell‐mediated influenza vaccines.

Here, we characterised the CD8+ T cell response towards the ‘universal’ HLA‐A*03:01‐restricted NP265‐IAV peptide, which was conserved in 98% of distinct IAV isolates analysed. The CD8+ T cell response varied in our five donors, from no activation to up to 17.9% of IFNγ/TNF+CD8+ T cells, similar to previously published studies. 21 , 42 Interestingly, there was no NP265‐IAV‐specific CD8+ T cell response in SG12 (Figure 1a), a donor that expressed the HLA‐A*03:02+ allomorph rather than HLA‐A*03:01 allomorph (Table 1). This allomorph differs from HLA‐A*03:01 by two residues located within the HLA cleft (HLA‐A*03:01: Asp151/Leu155, HLA‐A*03:02: Val151/Gln155) that will impact both peptide presentation and TCR interaction and could explain the lack of CD8+ T cell response observed. We determine the TCR repertoire directly ex vivo from three donors, which expanded on the previously published NP265‐IAV‐specific CD8+ T cell repertoire from a single donor. 46 We showed that NP265‐IAV‐specific CD8+ T cells utilise a private and diverse TCR repertoire. Conversely, the published HLA‐A*02:01‐restricted M158‐66‐specific TCR repertoire is extremely biased with public clonotypes shared between multiple individuals. 28 , 53 Interestingly, the crystal structure of the NP265‐IAV peptide in complex with HLA‐A*03:01 revealed a featureless conformation of the peptide similar to the one observed for the immunodominant M158‐66 peptide. The featureless conformation of the M158‐66 peptide was proposed as the molecular basis for the biased TCR repertoire in HLA‐A*02:01+ individuals containing public TCRs. 28 This is in contrast with the diverse and private NP265‐IAV‐specific TCR repertoire observed here for HLA‐A*03:01+ individuals, despite having a similarly featureless conformation. Diverse TCR repertoires are known to offer superior anti‐viral protection, 28 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 further highlighting the interest in NP265‐IAV as a potential CD8+ T cell‐mediated vaccine candidate.

Additionally, we assessed the phenotype of NP265‐IAV‐specific CD8+ T cells directly ex vivo. Interestingly, the majority of the NP265‐IAV‐specific CD8+ T cells displayed a naïve‐like (CD27+/CD45RA+) phenotypic profile in two out of three donors. This is unusual for peptide‐specific CD8+ T cells towards circulating viruses such as influenza, which typically display a higher proportion of cells with a memory phenotype. 37 , 48 , 49 Such a naïve‐like phenotype has been described before in the HLA‐A*68:01‐restricted NP145‐specific CD8+ T cells that likewise resulted in minimal and variable activation in HLA‐A*68:01+ individuals. 50 It may be possible that the naïve‐like T cells found in some donors, despite binding to NP265‐IAV tetramer, are not or weakly activated by the peptide, 59 , 60 which would explain the variability of response observed towards this epitope between donors.

We identified two NP265‐IAV homologous peptides derived from IBV and ICV, and both were able to form a stable complex with the HLA‐A*03:01 molecule; however, the NP265‐IAV and NP323‐IBV were more stable than NP270‐ICV complex. We characterised the immune response towards these homologous peptides as few peptides derived from IBV or ICV have been defined and are therefore generally understudied. 61 CD8+ T cell responses towards NP323‐IBV and NP270‐ICV were variable between donors, with NP323‐IBV stimulating a strong CD8+ T cell response in a single donor, while NP270‐ICV stimulated limited CD8+ T cell responses in all donors in both tetramer staining and ICS assays. Despite this variability, these results suggest that CD8+ T cells may display a preference for NP265‐IAV followed by NP323‐IBV and then NP270‐ICV; however, which viruses the individual has been exposed to, and when, are likely to influence this preference. These data also show that NP323‐IBV and NP270‐ICV are immunogenic and represent new influenza CD8+ T cell epitopes.

Moreover, despite the variable and sometimes minimal CD8+ T cell responses, CD8+ T cells stimulated with one of the homologous peptides could cross‐react towards the other peptides in some donors. This was most evident in CD8+ T cell lines generated against the NP265‐IAV peptide. CD8+ T cells capable of cross‐reacting towards homologous peptides could provide a level of protection towards distinct virus strains. Indeed, cross‐reactive CD8+ T cells have been shown to recognise and respond to distinct influenza virus strains 21 , 28 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 further supporting that these homologous peptides, and perhaps specifically the NP265‐IAV peptide, could be a good target in vaccination strategies.

The structures of NP265‐IAV and NP323‐IBV epitopes in complex with HLA‐A*03:01 show the peptides adopting a similar conformation, lying flat across the binding cleft, with a minor difference being a shorter anchor residue at P2‐V for NP323‐IBV verses that of P2‐L for NP265‐IAV. The similarity between the NP265‐IAV and NP323‐IBV conformation likely provides the basis for the CD8+ T cell cross‐reactivity observed. The side chain of the P8 residue in NP265‐IAV (P8‐H) is larger than that of NP323‐IBV (P8‐S), and this might be responsible for the stronger T cell response observed towards NP265‐IAV peptide. T cell cross‐reactivity is an essential mechanism for CD8+ T cells to be able to recognise and respond to a wide array of pathogens and their mutations using a limited number of cells. This is critically important, in the face of new viruses, such as SARS‐CoV‐2, 62 where prior exposure to other pathogens may generate CD8+ T cells capable of cross‐reacting with novel viruses. 39 , 40 , 41 We described here a thorough characterisation of the CD8+ T cell response towards NP265‐IAV, including the level, quality, phenotype, TCR repertoire used and peptide presentation. We have identified and characterised the CD8+ T cell response towards novel homologous peptides derived from IBV and ICV. We show that these three peptides are conserved and can be presented by HLA‐A*03:01, the 5th most common HLA‐A molecule worldwide. They can induce a CD8+ T cell response capable of cross‐reacting with the homologous peptides. This T cell cross‐reactivity, stronger towards the NP265‐IAV and NP323‐IBV peptides, is underpinned by similar peptide conformations revealed by the crystal structures of the peptide‐HLA complexes.

Together, these features would make these peptides, or perhaps more specifically, NP265‐IAV, a candidate that could be included in vaccine strategies. Furthermore, this study demonstrated the potential of CD8+ T cell cross‐reactivity in the protection against viral mutations, distinct virus strains, as well as newly emerging viruses.

Methods

Ethics, donors and HLA typing

All work was undertaken according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Human Research Ethics Committee at Monash University approved this work (HREC #19079). Whole blood donations were received from healthy volunteers who provided written and informed consent at the time of donation. Buffy coats were obtained from the Australian Red Cross Lifeblood who provide written and informed consent that their unused blood products be used for research at the time of donation. Donors were HLA typed at the Victorian Transplantation and Immunogenetics Service (VTIS, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) or using AlloSeq Tx17 (CareDx Pty Ltd, Fremantle, Australia), summary of HLA‐A locus typing of the donors used is found in Table 1.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated from whole blood or buffy coats using density gradient centrifugation, as previously described. 37 , 63 PBMCs were cryogenically stored until required.

Generation of peptide‐specific CD8 + T cell lines

CD8+ T cell lines were generated as previously described. 37 , 63 In summary, 1/3 of PBMCs were pulsed with 10 μm of individual peptides, washed twice, added to the remaining 2/3 PBMCs and cultured for 10–14 days in RPMI‐1640 (Gibco, Carlsbad, USA) supplemented with 1x Non‐essential amino acids (NEAA; Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, USA), 5 mm HEPES (Sigma‐Aldrich), 2 mm L‐glutamine (Sigma‐Aldrich), 1x penicillin/streptomycin/Glutamine (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA), 50 μm 2‐ME (Sigma‐Aldrich) and 10% heat‐inactivated (FCS; Thermofisher, Waltham, USA; Scientifix, Clayton, Australia). Cultures were supplemented with 10 IU mL−1 of IL‐2 two to three times weekly as required. CD8+ T cell lines were harvested for use, and residual cultures were cryogenically stored for subsequent analysis.

Intracellular cytokine staining assay

Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assay was completed as previously described. 37 Briefly, CD8+ T cell lines were co‐cultured with peptide‐pulsed C1R‐HLA‐A*03:01 at a 1:2 stimulators: responders (APC: T cell) ratio and incubated for 5 h in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, USA) and GolgiStop (BD Biosciences). Cells were stained with anti‐CD3‐BV480 (BD Biosciences), anti‐CD8‐PerCP‐Cy5.5 (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, USA), anti‐CD4‐BUV395 (BD Biosciences) and live/dead fixable near‐IR dead cell stain (Life Technologies) for 30 min, fixed and permeabilised using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences) for 20 min and then intracellularly stained with anti‐IFN‐γ‐BV421 (BD Biosciences) as well as anti‐TNF‐PECy7 (BD Biosciences) for 30 min. Samples were acquired on a BD Fortessa and analysed using FlowJo v10 (BD Biosciences). The gating strategy is shown in Supplementary figure 1a.

Tetramer staining

p‐HLA tetramers were prepared by conjugating purified biotinylated p‐HLA monomers to streptavidin at a 8:1 monomer to streptavidin molar ratio. Streptavidin‐PE (Invitrogen, Waltham, USA) was added slowly onto the monomer at 1/10 of the volume required and incubated for 10 min at room temperature, 10 times. CD8+ T cell lines were tetramer stained for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed and surface stained with anti‐CD3‐BV480 (BD Biosciences), anti‐CD8‐PerCP‐Cy5.5 (BD Biosciences), anti‐CD4‐BUV395 (BD Biosciences) and live/dead fixable near‐IR dead cell stain (Life Technologies). Cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and acquired on the BD LSR Fortessa and were analysed using Flowjo v10 (BD Biosciences). The gating strategy is shown in Supplementary figure 1b.

Ex vivo tetramer magnetic enrichment and single‐cell sorting

Tetramer magnetic enrichment and single‐cell PCR were undertaken as previously described. 37 , 47 Briefly, PBMCs from HLA‐A*03:01+ individuals were FcR blocked (Miltenyi Biotech) in MACS buffer (phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS)), 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma‐Aldrich); and 0.2 mm EDTA (Sigma‐Aldrich) for 15 min at 4°C. PBMCs were then stained with PE‐conjugated tetramer in MACS buffer for 1 h at room temperature, washed and labelled with anti‐PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech) at 4°C for 30 min. Epitope‐specific cells were enriched by passing twice over a LS magnetic column (Miltenyi Biotech) and surface stained with αCD3‐BV480 (BD Biosciences), αCD8‐PerCPCy5.5 (BD Biosciences), Live/Dead‐NIR (Life Technologies), αCD14‐APCH7 (BD Biosciences), αCD4‐APCH7 (BD Biosciences), αCD19‐APCH7 (BD Biosciences), αCD27‐BV711 (BD Biosciences), αCD45RA‐FITC (BD Biosciences), αCCR7‐PECy7 (BD Biosciences) and αCD95‐BV421 (BD Biosciences) at 4°C in the dark. Cells were resuspended in sort buffer (PBS, 0.1% BSA; Gibco, CA, USA), and tetramerhigh/CD8+ T cells were single‐cell sorted directly into Twin‐Tech PCR plates (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) on an Aria Fusion (BD Biosciences) and were stored at −80°C until used. The gating strategy is shown in Supplementary figure 1c.

Single‐cell multiplex PCR

Single‐cell multiplex PCR was carried out as previously described. 37 , 47 In brief, cDNA was generated using 1/20 of the manufacturer's recommendation of the VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) with 0.1% Triton X (Sigma‐Aldrich). Nested PCR was performed over two rounds, comprising 40 α‐ and 27 β‐chains external (first round) and internal primers (second round). PCR products were visualised on a 2% agarose gel, and positive PCR products were purified using ExoSAP (GE Healthcare, Chicago, USA) and were sequenced at Micromon (Monash University, Australia). Sequences were analysed using Finch TV (Geospiza, Denver, USA) and IMGT software. 64 , 65 TCR sequences are reported using IMGT nomenclature, 64 , 65 and all CDR3 sequences shown are productive (no stop codons and an in‐frame junction). The results are summarised in Table 2.

Protein expression, refold and purification

DNA plasmids encoding HLA‐A*03:01 α‐chain and β2‐microglobulin were transformed separately into a BL21 strain of Escherichia Coli, as previously described. 63 Recombinant proteins were expressed individually, where inclusion bodies were extracted and purified from the transformed E. coli cells. Soluble pHLA complexes were produced by refolding 30 mg of HLA‐A*03:01 with 10 mg of β‐2‐microglobulin and 5 mg of either NP265‐IAV, NP323‐IBV or NP270‐ICV peptide (Genscript, Piscataway, USA) into a buffer of 3 m Urea (Univar solutions, USA), 0.5 m L‐Arginine (Sigma‐Aldrich), 0.1 m Tris–HCl pH 8.0 (Fisher Bioreagents), 2.5 mm EDTA pH 8.0 (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, USA), 5 mm Glutathione (reduced) (Goldbio, St Louis, USA) and 1.25 mm Glutathione (oxidised; Goldbio) for 3 h. The refold mixture was dialysed into 10 mm Tris–HCl pH 8.0 (Fisher Bioreagents), and soluble pHLA was purified using anion exchange chromatography using a HiTrapQ column (GE Healthcare).

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry

Differential scanning fluorimetry was performed using a Qiagen RG6 real‐time PCR machine by heating up pHLA samples in 10 mm Tris–HCl pH 8.0 (Fisher Bioreagents), 150 mm NaCl (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), at two concentrations (5 and 10 mm) in duplicate, from 30 to 95°C at a rate of 0.5°C/min, with the emission channel set to yellow (excitation of ~530 nm and detection at ~557 nm). All samples contained a final concentration of 10X SYPRO Orange Dye (Invitrogen). Data were plotted using GraphPad Prism 9 (version 9.0.0) and normalised, and the Tm value was determined at the 50% point of maximal fluorescence intensity and summarised in Table 4.

Crystallisation and structural determination

Crystals of pHLA complexes were grown via sitting‐drop, vapour diffusion method at 20°C with a protein: reservoir drop ratio of 1:1, at a concentration of 7 mg mL−1 or 10 mg mL−1 in 10 mm Tris–HCl pH 8.0 (Fisher Bioreagents), 150 mm NaCl (Merck). Crystals of HLA‐A*03:01‐NP265‐IAV were grown in 0.2 m ammonium sulphate (Hampton, Aliso Viejo, USA), 0.1 m Bis‐Tris propane pH 6.5 (Hampton), 22% PEG 3350 (Sigma‐Aldrich). HLA‐A*03:01‐NP323‐IBV were grown in 1 m trisodium citrate (Hampton) and 0.1 m sodium cacodylate pH 6.5 (Hampton). These crystals were soaked in a cryoprotectant containing the mother liquor supplemented with 20% EG (Sigma‐Aldrich) and then flash‐frozen in liquid nitrogen. The data were collected on the MX2 beamline at the Australian Synchrotron, part of ANSTO, Australia. 66 The data were processed using XDS, 67 and the structures were determined by molecular replacement using the PHASER programme 68 from the CCP4 suite 69 with a model of 3RL1. 70 , 71 Manual model building was conducted using COOT 72 followed by refinement with BUSTER. 73 The final model has been validated using the wwPDB OneDep System with the accession numbers of 7UC5 for HLA‐A*03:01‐NP265‐IAV and 7MLE for HLA‐A*03:01‐NP323‐IBV. The final refinement statistics are summarised in Table 5. All molecular graphics representations were created using PyMOL.

Author Contributions

Andrea T Nguyen: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Hiu Ming Peter Lau: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation. Hannah Sloane: Formal analysis; visualization. Dhilshan Jayasinghe: Investigation; methodology. Nicole Mifsud: Methodology; resources. Demetra SM Chatzileontiadou: Investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Emma Grant: Formal analysis; funding acquisition; methodology; supervision; validation; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Christopher Szeto: Formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Stephanie Gras: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; project administration; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary figures 1‐5

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Monash Facilities (Flow Core, Macromolecular Crystallisation Facility, Micromon sequencing Facility); Victorian Transplantation and Immunogenetics Service (VTIS, Melbourne, Australia), Melbourne, for HLA Typing; Professor Kedzierska (Peter Doherty Institute, Melbourne) for reagents; and MX team for assistance at the Australian Synchrotron. This research was undertaken in part using the MX2 beamline at the Australian Synchrotron, part of ANSTO, and made use of the Australian Cancer Research Foundation (ACRF) detector. The authors thank all the blood donors who took part in this study. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). ATN is supported by an AINSE Postgraduate Research Award, HS was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, EJG was supported by an NHMRC CJ Martin Fellowship (#1110429) and is supported by an Australian Research Council DECRA (DE210101479) and an AINSE Early Career Researcher Grant, and SG is supported by an NHMRC SRF (#1159272).

Contributor Information

Emma J Grant, Email: e.grant@latrobe.edu.au.

Christopher Szeto, Email: c.szeto@latrobe.edu.au.

Stephanie Gras, Email: s.gras@latrobe.edu.au.

References

- 1. Grant EJ, Quinones‐Parra SM, Clemens EB, Kedzierska K. Human influenza viruses and CD8+ T cell responses. Curr Opin Virol 2016; 16: 132–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krammer F, Smith GJD, Fouchier RAM et al. Influenza. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018; 4: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thompson WW, Weintraub E, Dhankhar P et al. Estimates of US influenza‐associated deaths made using four different methods. Influenza Other Respi Viruses 2009; 3: 37–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ariyoshi T, Tezuka J, Yasudo H et al. Enhanced airway hyperresponsiveness in asthmatic children and mice with A(H1N1)pdm09 infection. Immun Inflamm Dis 2021; 9: 457–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao X, Gang X, He G et al. Obesity increases the severity and mortality of Influenza and COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020; 11: 595109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lina B, Georges A, Burtseva E et al. Complicated hospitalization due to influenza: results from the Global Hospital Influenza Network for the 2017‐2018 season. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schanzer DL, Langley JM, Tam TW. Co‐morbidities associated with influenza‐attributed mortality, 1994‐2000, Canada. Vaccine 2008; 26: 4697–4703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matsuzaki Y, Katsushima N, Nagai Y et al. Clinical features of influenza C virus infection in children. J Infect Dis 2006; 193: 1229–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sederdahl BK, Williams JV. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of Influenza C virus. Viruses 2020; 12: 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Asha K, Kumar B. Emerging Influenza D virus threat: What We Know so Far! J Clin Med 2019; 8: 192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koutsakos M, Wheatley AK, Loh L et al. Circulating TFH cells, serological memory, and tissue compartmentalization shape human influenza‐specific B cell immunity. Sci Transl Med 2018; 10: eaan8405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Flannery B, Kondor RJG, Chung JR et al. Spread of antigenically drifted Influenza A(H3N2) Viruses and vaccine effectiveness in the United States during the 2018‐2019 Season. J Infect Dis 2020; 221: 8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Okoli GN, Racovitan F, Abdulwahid T, Righolt CH, Mahmud SM. Variable seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness across geographical regions, age groups and levels of vaccine antigenic similarity with circulating virus strains: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the evidence from test‐negative design studies after the 2009/10 influenza pandemic. Vaccine 2021; 39: 1225–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wells MA, Albrecht P, Ennis FA. Recovery from a viral respiratory infection. I. Influenza pneumonia in normal and T‐deficient mice. J Immunol 1981; 126: 1036–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bender BS, Croghan T, Zhang L, Small PA Jr. Transgenic mice lacking class I major histocompatibility complex‐restricted T cells have delayed viral clearance and increased mortality after influenza virus challenge. J Exp Med 1992; 175: 1143–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McMichael AJ, Gotch FM, Noble GR, Beare PA. Cytotoxic T‐cell immunity to influenza. N Engl J Med 1983; 309: 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sridhar S, Begom S, Bermingham A et al. Cellular immune correlates of protection against symptomatic pandemic influenza. Nat Med 2013; 19: 1305–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Z, Wan Y, Qiu C et al. Recovery from severe H7N9 disease is associated with diverse response mechanisms dominated by CD8+ T cells. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 6833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Z, Zhu L, Nguyen THO et al. Clonally diverse CD38+HLA‐DR+CD8+ T cells persist during fatal H7N9 disease. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heiny AT, Miotto O, Srinivasan KN et al. Evolutionarily conserved protein sequences of influenza a viruses, avian and human, as vaccine targets. pLoS One 2007; 2: e1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Quinones‐Parra S, Grant E, Loh L et al. Preexisting CD8+ T‐cell immunity to the H7N9 influenza A virus varies across ethnicities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 1049–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pleguezuelos O, James E, Fernandez A et al. Efficacy of FLU‐v, a broad‐spectrum influenza vaccine, in a randomized phase iIb human influenza challenge study. NPJ Vaccines 2020; 5: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clemens EB, van de Sandt C, Wong SS, Wakim LM, Valkenburg SA. Harnessing the power of T cells: the promising hope for a universal Influenza vaccine. Vaccines (Basel) 2018; 6: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Szeto C, Lobos CA, Nguyen AT, Gras S. TCR recognition of peptide‐MHC‐I: rule makers and breakers. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 22: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Robinson J, Barker DJ, Georgiou X, Cooper MA, Flicek P, Marsh SGE. IPD‐IMGT/HLA database. Nucleic Acids Res 2020; 48: D948–D955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clemens EB, Grant EJ, Wang Z et al. Towards identification of immune and genetic correlates of severe influenza disease in Indigenous Australians. Immunol Cell Biol 2016; 94: 367–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Valkenburg SA, Quinones‐Parra S, Gras S et al. Acute emergence and reversion of influenza A virus quasispecies within CD8+ T cell antigenic peptides. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Valkenburg SA, Josephs TM, Clemens EB et al. Molecular basis for universal HLA‐A*0201‐restricted CD8+ T‐cell immunity against influenza viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016; 113: 4440–4445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boon AC, de Mutsert G, Graus YM et al. Sequence variation in a newly identified HLA‐B35‐restricted epitope in the influenza A virus nucleoprotein associated with escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Virol 2002; 76: 2567–2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berkhoff EG, Boon AC, Nieuwkoop NJ et al. A mutation in the HLA‐B*2705‐restricted NP383‐391 epitope affects the human influenza A virus‐specific cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte response in vitro. J Virol 2004; 78: 5216–5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gras S, Kedzierski L, Valkenburg SA et al. Cross‐reactive CD8+ T‐cell immunity between the pandemic H1N1‐2009 and H1N1‐1918 influenza A viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 12599–12604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hillaire MLB, Vogelzang‐van Trierum SE, Kreijtz J et al. Human T‐cells directed to seasonal influenza A virus cross‐react with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) and swine‐origin triple‐reassortant H3N2 influenza viruses. J Gen Virol 2013; 94: 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tu W, Mao H, Zheng J et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes established by seasonal human influenza cross‐react against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. J Virol 2010; 84: 6527–6535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee LY, do LA H, Simmons C et al. Memory T cells established by seasonal human influenza A infection cross‐react with avian influenza A (H5N1) in healthy individuals. J Clin Invest 2008; 118: 3478–3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kreijtz JH, de Mutsert G, van Baalen CA, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Rimmelzwaan GF. Cross‐recognition of avian H5N1 influenza virus by human cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte populations directed to human influenza A virus. J Virol 2008; 82: 5161–5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van de Sandt CE, Kreijtz JH, de Mutsert G et al. Human cytotoxic T lymphocytes directed to seasonal influenza A viruses cross‐react with the newly emerging H7N9 virus. J Virol 2014; 88: 1684–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grant EJ, Josephs TM, Loh L et al. Broad CD8+ T cell cross‐recognition of distinct influenza A strains in humans. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 5427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee CH, Pinho MP, Buckley PR et al. Potential CD8+ T cell cross‐reactivity against SARS‐CoV‐2 conferred by other Coronavirus strains. Front Immunol 2020; 11: 579480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Braun J, Loyal L, Frentsch M et al. SARS‐CoV‐2‐reactive T cells in healthy donors and patients with COVID‐19. Nature 2020; 587: 270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Le Bert N, Tan AT, Kunasegaran K et al. SARS‐CoV‐2‐specific T cell immunity in cases of COVID‐19 and SARS, and uninfected controls. Nature 2020; 584: 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lineburg KE, Grant EJ, Swaminathan S et al. CD8+ T cells specific for an immunodominant SARS‐CoV‐2 nucleocapsid epitope cross‐react with selective seasonal coronaviruses. Immunity 2021; 54: 1055–1065 e1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. DiBrino M, Tsuchida T, Turner RV, Parker KC, Coligan JE, Biddison WE. HLA‐A1 and HLA‐A3 T cell epitopes derived from influenza virus proteins predicted from peptide binding motifs. J Immunol 1993; 151: 5930–5935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Solberg OD, Mack SJ, Lancaster AK et al. Balancing selection and heterogeneity across the classical human leukocyte antigen loci: a meta‐analytic review of 497 population studies. Hum Immunol 2008; 69: 443–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grant E, Wu C, Chan KF et al. Nucleoprotein of influenza A virus is a major target of immunodominant CD8+ T‐cell responses. Immunol Cell Biol 2013; 91: 184–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sant S, Quinones‐Parra SM, Koutsakos M et al. HLA‐B*27:05 alters immunodominance hierarchy of universal influenza‐specific CD8+ T cells. pLoS Pathog 2020; 16: e1008714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pizzolla A, Nguyen TH, Sant S et al. Influenza‐specific lung‐resident memory T cells are proliferative and polyfunctional and maintain diverse TCR profiles. J Clin Invest 2018; 128: 721–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grant EJ, Josephs TM, Valkenburg SA et al. Lack of heterologous cross‐reactivity toward HLA‐A*02:01 restricted viral epitopes is underpinned by distinct alphabetaT cell receptor signatures. J Biol Chem 2016; 291: 24335–24351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nguyen TH, Bird NL, Grant EJ et al. Maintenance of the EBV‐specific CD8+ TCRalphabeta repertoire in immunosuppressed lung transplant recipients. Immunol Cell Biol 2017; 95: 77–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nguyen THO, Sant S, Bird NL et al. Perturbed CD8+ T cell immunity across universal influenza epitopes in the elderly. J Leukoc Biol 2018; 103: 321–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. van de Sandt CE, Clemens EB, Grant EJ et al. Challenging immunodominance of influenza‐specific CD8+ T cell responses restricted by the risk‐associated HLA‐A*68:01 allomorph. Nat Commun 2019; 10: 5579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang Y, Aevermann BD, Anderson TK et al. Influenza research database: an integrated bioinformatics resource for influenza virus research. Nucleic Acids Res 2017; 45: D466–D474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nguyen AT, Szeto C, Gras S. The pockets guide to HLA class I molecules. Biochem Soc Trans 2021; 49: 2319–2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ishizuka J, Stewart‐Jones GB, van der Merwe A, Bell JI, McMichael AJ, Jones EY. The structural dynamics and energetics of an immunodominant T cell receptor are programmed by its Vbeta domain. Immunity 2008; 28: 171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Meyer‐Olson D, Shoukry NH, Brady KW et al. Limited T cell receptor diversity of HCV‐specific T cell responses is associated with CTL escape. J Exp Med 2004; 200: 307–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ganusov VV, Goonetilleke N, Liu MK et al. Fitness costs and diversity of the cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response determine the rate of CTL escape during acute and chronic phases of HIV infection. J Virol 2011; 85: 10518–10528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ladell K, Hashimoto M, Iglesias MC et al. A molecular basis for the control of preimmune escape variants by HIV‐specific CD8+ T cells. Immunity 2013; 38: 425–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Valkenburg SA, Day EB, Swan NG et al. Fixing an irrelevant TCR alpha chain reveals the importance of TCRβ diversity for optimal TCR alpha beta pairing and function of virus‐specific CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol 2010; 40: 2470–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Messaoudi I, Guevara Patino JA, Dyall R, LeMaoult J, Nikolich‐Zugich J. Direct link between mhc polymorphism, T cell avidity, and diversity in immune defense. Science 2002; 298: 1797–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gras S, Chadderton J, Del Campo CM et al. Reversed T cell receptor docking on a major histocompatibility class I complex limits involvement in the immune response. Immunity 2016; 45: 749–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zareie P, Szeto C, Farenc C et al. Canonical T cell receptor docking on peptide‐MHC is essential for T cell signaling. Science 2021; 372: eabe9124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Koutsakos M, Illing PT, Nguyen THO et al. Human CD8+ T cell cross‐reactivity across influenza A. B and C viruses Nat Immunol 2019; 20: 613–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ledford H. How 'killer' T cells could boost COVID immunity in face of new variants. Nature 2021; 590: 374–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Szeto C, Chatzileontiadou DSM, Nguyen AT et al. The presentation of SARS‐CoV‐2 peptides by the common HLA‐A*02:01 molecule. iScience 2021; 24: 102096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Giudicelli V, Brochet X, Lefranc MP. IMGT/V‐QUEST: IMGT standardized analysis of the immunoglobulin (IG) and T cell receptor (TR) nucleotide sequences. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2011; 2011: 695–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Brochet X, Lefranc MP, Giudicelli V. IMGT/V‐QUEST: the highly customized and integrated system for IG and TR standardized V‐J and V‐D‐J sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36: W503–W508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. McPhillips TM, McPhillips SE, Chiu HJ et al. Blu‐Ice and the Distributed Control System: software for data acquisition and instrument control at macromolecular crystallography beamlines. J Synchrotron Radiat 2002; 9: 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2010; 66: 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. McCoy AJ, Grosse‐Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst 2007; 40: 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 1994; 50: 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhang S, Liu J, Cheng H et al. Structural basis of cross‐allele presentation by HLA‐A*0301 and HLA‐A*1101 revealed by two HIV‐derived peptide complexes. Mol Immunol 2011; 49: 395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gras S, Saulquin X, Reiser JB et al. Structural bases for the affinity‐driven selection of a public TCR against a dominant human cytomegalovirus epitope. J Immunol 2009; 183: 430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2010; 66: 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bricogne G, Blanc E, Brandl M et al. Buster version 2.10. Cambridge, UK: Global Phasing Ltd; 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures 1‐5