Abstract

The growing threat of vector-borne diseases, highlighted by recent epidemics, has prompted increased focus on the fundamental biology of vector-virus interactions. To this end, experiments are often the most reliable way to measure vector competence (the potential for arthropod vectors to transmit certain pathogens). Data from these experiments are critical to understand outbreak risk, but – despite having been collected and reported for a large range of vector-pathogen combinations – terminology is inconsistent, records are scattered across studies, and the accompanying publications often share data with insufficient detail for reuse or synthesis. Here, we present a minimum data and metadata standard for reporting the results of vector competence experiments. Our reporting checklist strikes a balance between completeness and labor-intensiveness, with the goal of making these important experimental data easier to find and reuse in the future, without much added effort for the scientists generating the data. To illustrate the standard, we provide an example that reproduces results from a study of Aedes aegypti vector competence for Zika virus.

Subject terms: Viral transmission, Model invertebrates

Introduction

Vector competence is an arthropod vector’s ability to transmit a pathogen after exposure to the pathogen1–3. It combines the intrinsic potential of a pathogen to successfully enter and replicate within the vector, and then disseminate to, replicate within, and release from the vector’s salivary glands into the saliva at sufficiently high concentration to initiate infection in the next vertebrate host. Quantifying this process at each step within the vector is fundamental to understanding and predicting vector-borne disease transmission.

Due to the inherent complexity of arboviral transmission, experimental studies of vector competence are also necessarily complex, and may report a number of types of data. Experimental settings add additional constraints, as controlled laboratory conditions are themselves inherently complex, and vector competence is highly responsive to some of these conditions (e.g., the temperature at which experiments take place). While the complexity and requisite scientific skills make these experiments challenging, their importance and value – particularly in response to vector-borne disease outbreaks of international concern – cannot be overstated, and has led to increasing numbers of these experiments. However, the complexity of the experiments, and the variety of conditions under which they are conducted, make it difficult to meticulously share (and synthesize) all relevant metadata, especially with consistent enough terminology to compare results across studies4. Because primary data are not reported in a standardized manner, opportunities are being lost to advance science and public health.

Here, we propose a minimum data standard for reporting the results of vector competence experiments. The motivation to create and disseminate data standards for reporting is part of a broad effort across scientific disciplines to preserve data for future use, recover existing data that may be unsearchable for many reasons, and establish open principles for harmonizing those data to better leverage the effort of the larger community of research5–10. In particular, the FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) guiding principles11,12 were created to improve the infrastructure supporting the reuse of scholarly data, including public data archiving13. These principles aim to maximize the value of research investments and digital publishing, and have been adopted into both efforts to synthesize and populate databases for use by the scientific community, and into the language of a growing number of funders’ reporting requirements. Tailoring FAIR principles to different subfields of scientific research requires consideration of the specific kinds of data that are regularly generated, and how they would best be reported. For example, the recently published minimum data standard MIReAD (Minimum Information for Reusable Arthropod abundance Data) aims to improve the transparency and reusability of arthropod abundance data14, thereby improving the benefits reaped from data sharing, and reducing the cost of obtaining research results. Importantly, these data standards do not aim to provide guidance on how experiments are conducted, nor guide research, but provide a reporting standard flexible enough to accommodate the outputs of most of these experiments.

In this paper, we characterize the key steps of vector competence experiments, and the data generated at each stage, as a means to establish common guidelines for data reporting that follow FAIR principles. Due to the long history of experimental work with mosquito vectors (and the incomparable role it plays in efforts to decrease the global burden of vector-borne disease), we propose a minimum data standard focused on capturing results from studies that test pairs of mosquitoes and arboviruses. However, we intentionally aimed to make these standards flexible, extendable, and adaptable, and therefore applicable to additional systems (e.g., experiments with ticks and other vectors, or mechanical transmission components of Chagas disease by triatomine insects).

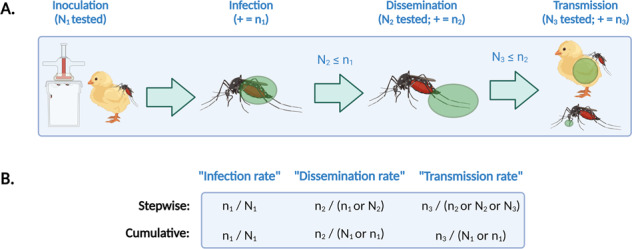

Methods

Tables 1–4 provide a standard checklist for data that arise from, and metadata about, vector competence experiments (and a blank Excel file with these columns is available as Supplementary File 1, for researchers to use directly as a template when reporting primary data along with publications). We have designed these standards with a particular focus on applicability to mosquito-borne arboviruses, and on capturing aspects of experimental design that are known confounders (e.g., rearing and experimental temperature, or inoculation route and dose)15–19. While reviewing the literature to design the standard, we found that many of the rates reported (e.g., transmission rate) are derived from discrete and detailed experimental information, yet the original raw data may never be reported, and is often impossible to reconstruct from provided bar or line charts. Moreover, the derived quantities often follow different calculations, with (usually intentional but) very different biological meaning (e.g., the difference between ‘dissemination rate’ and ‘disseminated infection rate’ which are often used interchangeably) (Fig. 1)20. Given these choices, it may be misleading to directly compare derived rates across studies. To avoid this problem, we suggest that reporting raw numbers of both vectors tested and those found positive for each basic metric may prevent confusion across study terminology, while still allowing derived rates to be calculated and reported in publications.

Table 2.

A minimum standard for virus metadata.

| Variable | Descriptor |

|---|---|

| Virus | Virus species name (using appropriate species concept) |

| Viral lineage | Virus intraspecific lineage (e.g., Asian lineage of Zika virus) if known |

| Viral strain | Viral strain name (if one exists) |

| Viral GenBank accession | Accession number for viral sequences |

| Viral origin (locality) | Where a virus was originally sourced from in humans or wild animals |

| Viral origin (year) | When a viral strain was sourced from humans or wild animals |

| Viral history (passage) | Cell type and passage number (e.g., Vero cells, passage 2) |

| Virus history (freshness) | Was viral stock frozen at any stage in the process, or was it collected fresh and directly used in experiments? |

Table 3.

A minimum standard for experimental metadata.

| Variable | Descriptor |

|---|---|

| Exposure route | How were vectors exposed (e.g., blood meal, live animal, intrathoracic injection) |

| Host (exp.) | Host species used for live animal or blood meal exposure, and to test transmission, if applicable (either for live animal or for origin of blood meal, if known) |

| Host lineage/origin | Host intraspecific lineage name, or origin (e.g., if wild-caught), if applicable (either for live animal or for origin of blood meal, if known) |

| Diagnostic (virem.) | If host viremia was measured in live animal, diagnostic method used |

| Titer | Host viremia if live animal; concentration of virus for blood meal or intrathoracic inoculation |

| Units | Units for titer (above; e.g., PFU/ml, FFU/ml, vRNAs/ml, etc.) |

| Dose | Dose of live virus injected via intrathoracic inoculation, if applicable |

| Units | Units for dose (above) |

| Temp. (reared) | Temperature at which vectors are reared (preferably Celsius). [If temperature is not held constant, can be used to report mean, with additional columns added for e.g., “amplitude,” or minimum and maximum temperatures] |

| Temp. (EIT) | Temperature at which extrinsic incubation happens (preferably Celsius). [If temperature is not held constant, can be used to report mean, with additional columns added for e.g., “amplitude,” or minimum and maximum temperatures] |

| DPI | Days post-infection (i.e., post-exposure) |

Table 1.

A minimum standard for vector metadata.

| Variable | Descriptor |

|---|---|

| Vector | Full Latin name (species). [Vector taxonomy should be as up-to-date as possible at the time of publication, potentially including additional columns anchored to taxonomic reference databases (e.g., “NCBI:txid7159” is a stable reference for Aedes aegypti in the NCBI taxonomic backbone, and will continue to be even if the name changes in the future).] |

| Vector subsp. | Vector subspecies epithet if applicable (e.g., formosus) |

| Vector strain | Lab reared vector strain name (if one exists) |

| Vector origin (country) | Wild source for original vector collection (country) |

| Vector origin (locality) | Wild source for original vector collection (more detailed text string) |

| Vector origin (year) | Year of wild vector collection |

| Vector gen. | Generation of vectors in lab colony |

Table 4.

A minimum standard for experimental outcome data.

| Variable | Descriptor |

|---|---|

| Body part (inf.) | Vector tissue or body part used to establish infection (e.g., midgut, whole body, carcass, etc.) |

| Diagnostic (inf.) | How vector infection was established (e.g., qRT-PCR, virus isolation, etc.) |

| # tested (inf.) | Number of vectors tested for infection |

| # inf. | Number of vectors with viral infection |

| Body part (dissem.) | Vector tissue or body part used to establish dissemination (e.g., legs or wings) |

| Diagnostic (dissem.) | How viral dissemination in the vector was established (e.g., qRT-PCR, viral isolation, etc.) |

| # tested (dissem.) | Number of vectors tested for dissemination |

| # dissem. | Number of vectors with viral dissemination |

| Host (transm.) | Host species used to test transmission, if tested using live animal exposure to infected vectors |

| Tissue (transm.) | Tissue (e.g., saliva) used to test ability to transmit (not applicable if live animal exposure and infection was used to test transmission) |

| Diagnostic (transm.) | How viral transmission in the exposure host (e.g., qRT-PCR, clinical symptoms) or vector tissue (e.g., plaque assay) was established |

| # tested (transm.) | Number of vectors tested for ability to transmit |

| # transm. | Number of vectors that were able to transmit |

Fig. 1.

(A) For mosquito-borne viruses, vector competence experiments follow a relatively standardized format. Mosquitoes are inoculated with a virus through intrathoracic inoculation or by feeding on a live host or a prepared blood meal; infection and dissemination are measured by testing different mosquitoes tissues; and transmission is measured either by testing saliva or salivary glands, or by allowing mosquitoes to feed on a susceptible host and infect them. (B) The results are best understood as rates, but each rate might be reported in several formats; this is further complicated if only a subset of mosquitoes are tested at each stage (e.g., if some mosquitoes die between stages of the experiment). As a result, reporting only denominators leaves much to be desired. Instead–as our data standard reflects–the clearest presentation of raw data is to report total counts of tested and positive mosquitoes at each stage. (“+” indicates how many mosquitoes test positive out of the total sample). Created with BioRender.com.

Finally, we note that our goal here is only to provide a minimum standard for even the most basic experiment; more specialized designs may require additional columns, and bespoke solutions to those problems may, as they are developed, become future standardized templates. For example, experimental designs focused on coinfection with additional microbes (e.g., Wolbachia; insect-specific viruses, or ISVs) will likely need to reproduce many of the “Virus metadata” variables as a set of “Coinfection metadata” variables, and might also require additional fields. Once standardized, this could be incorporated into a future version of the base template, encouraging more researchers to assay and report the microbes present in laboratory populations, and thereby reducing unquantified heterogeneity among experimental designs.

Results

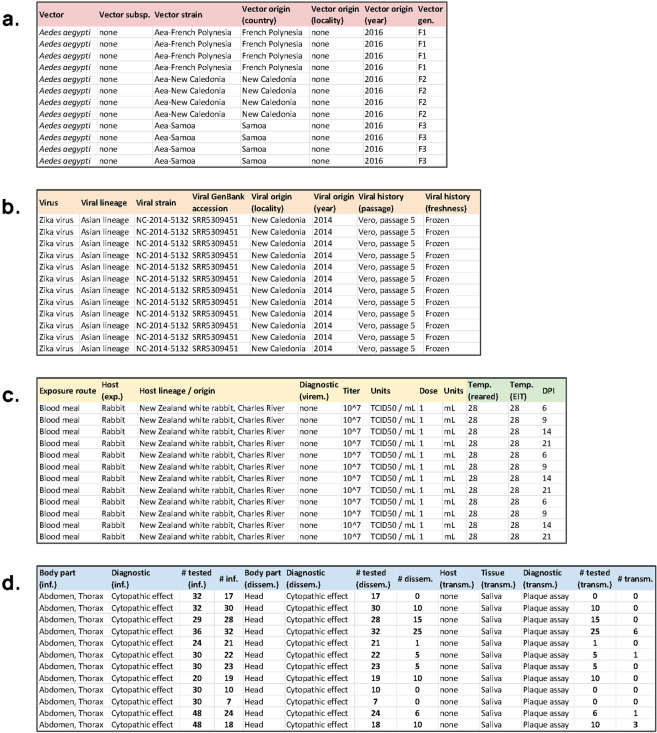

To illustrate the data standard in practice, we revisit a study by Calvez et al.21 of vector competence for Zika virus in Aedes mosquitoes relevant to Pacific islands. Unlike many studies, which report results in a mix of summary tables and bar or line graphs, Calvez et al. provided very detailed summaries of raw data in their supplementary tables (Table 5). Because they report results in a structured format, with detailed data on the experimental results, other studies have been able to gather their findings alongside other studies (e.g., Table 6). However, these aggregate datasets often lack important dimensions of metadata. To illustrate how researchers might report primary results in the future, we present a metadata-complete version of the results from Calvez et al., that meets the minimum data standard we propose, as interpreted from both their Methods and Supplementary Table 1 (Fig. 2)22. In rare cases where information was unavailable (e.g., detailed locality information on the origin of mosquitoes), we use “none” to indicate that no data was provided.

Table 5.

An example dataset from a set of vector competence experiments with Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and Zika virus, as reported in Supplementary Table 1 of Calvez et al.21 Additional details on experimental protocols are provided in the methods section, and the study reports an additional set of experiments with Aedes polynesiensis mosquitoes as well (not shown).

| 6 dpi | 9 dpi | 14 dpi | 21 dpi | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of infection (Number of infected bodies/number of mosquitoes tested) | Aea-New Caledonia | 88% (21/24) | 73% (22/30) | 77% (23/30) | 95% (19/20) |

| Aea-Samoa | 33% (10/30) | 23% (7/30) | 50% (24/48) | 38% (18/48) | |

| Aea-French Polynesia | 53% (17/32) | 94% (30/32) | 97% (28/29) | 89% (32/36) | |

| % of dissemination (Number of infected heads/number of infected bodies) | Aea-New Caledonia | 5% (1/21) | 23% (5/22) | 22% (5/23) | 53% (10/19) |

| Aea-Samoa | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/7) | 25% (6/24) | 56% (10/18) | |

| Aea-French Polynesia | 0% (0/17) | 33% (10/30) | 54% (15/28) | 78% (25/32) | |

| % of transmission (Number of infected saliva/number of infected heads) | Aea-New Caledonia | 0% (0/1) | 20% (1/5) | 0% (0/5) | 0% (0/10) |

| Aea-Samoa | 0% (0/0) | 0% (0/0) | 17% (1/6) | 30% (3/10) | |

| Aea-French Polynesia | 0% (0/0) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/15) | 24% (6/25) | |

| % of efficiency (Number of infected saliva/number of mosquitoes tested) | Aea-New Caledonia | 0% (0/24) | 3% (1/30) | 0% (0/30) | 0% (0/20) |

| Aea-Samoa | 0% (0/30) | 0% (0/30) | 2% (1/48) | 6% (3/48) | |

| Aea-French Polynesia | 0% (0/32) | 0% (0/32) | 0% (0/29) | 17% (6/36) |

Table 6.

An example of how the same data (Table 5) could currently be reported in a synthetic format, reproduced in the same format from a table of the results of Aedes aegypti vector competence experiments from several studies, assembled by Souza-Neto et al.27.

| Virus | Mosquito origin | Virus genotype and strain | Vector Competence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection Route, virus dose | Results | |||

| ZIKV | French Polynesia | NC-2014-5132, NC | BM, 107 TCID50/mL | IR: 53 at 6 dpi; 94 at 9 dpi; 97 at 14 dpi, 89 at 21 dpi; TR 0 between 6 and 9 dpi; 24 at 21 dpi |

| NC [New Caledonia] | IR: 88 at 6 dpi; 73 at 9 dpi; 77 at 14 dpi, 95 at 21 dpi; TR 0 at 6dpi, 3 at 9 dpi, 0 between 14 and 21 dpi | |||

| Samoa | IR: 33 at 6 dpi; 23 at 9 dpi; 50 at 14 dpi, 38 at 21 dpi; TR 0 between 6 and 9 dpi; 17 at 14 dpi and 30 at 21 dpi | |||

Fig. 2.

The same dataset (Table 5) in a metadata-complete format with standardized columns, reporting (a) ID’s for experimental group, and vector species and vector metadata; (b) virus species and viral metadata; (c) experimental protocols; and (d) the standard results in infection/dissemination/transmission, with clear data on diagnostics and denominators.

Discussion

Vector competence experiments can have very real-world and urgent applications, informing how health decision-makers assess risks like “Are temperate vectors permissive to a tropical outbreak spreading north?”23,24 or “Is an ongoing epizootic likely to spill over into humans?”25,26 However, a lack of standardized data reporting is a barrier to reuse and synthesis in this growing field4. In turn, current efforts largely remain disconnected from one another, without any central repository that immortalizes these studies’ findings. Some studies have begun to scale this gap: one study compiled a table of results from several dozen studies of Aedes aegypti and various arboviruses (see Table 6)27. More recently, another study compiled a dataset of 68 experimental studies that tested 111 combinations of Australian mosquitoes and arboviruses, and analyzed biological signals in the aggregated data28. These types of efforts are painstaking, requiring substantial manual curation of metadata, and hundreds more experiments are reported in the literature, yet remain unsynthesized due to this barrier.

Going forward, adopting a data reporting standard might make it easier for researchers to share data in reusable formats, and – in doing so – would support the creation of a database following this format. This could also help explain or resolve the issue of why results across studies are inconsistent, especially historical studies and newer studies, which often use newer and more sensitive techniques (e.g., qRT-PCR as compared to PFU). Storing these data in aggregate would facilitate formal meta-analysis and create new opportunities for quantitative modeling. It would also have practical benefits for researchers, assisting them in disseminating their findings, and potentially reducing duplication of research. To that point, a recent synthetic study found that while some combinations (e.g., Ae. aegypti and Zika virus) are extremely well studied, over 90% of mosquito-virus pairs might never have been tested experimentally. Standardizing data more broadly might help researchers identify and fill these gaps, simultaneously supporting infectious disease preparedness and fundamental research into the science of the host-virus network29.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding to Verena (viralemergence.org) from the U.S. National Science Foundation, including NSF BII 2021909 and NSF BII 2213854. SJR was additionally supported by NSF DBI 2016265 CIBR: VectorByte: A Global Informatics Platform for studying the Ecology of Vector-Borne Diseases.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: C.J.C. and S.J.R.; data collection: V.Y.W.; literature synthesis and first drafting: V.Y.W., C.J.C., S.J.R.; writing and editing: all authors.

Data availability

All example data and a blank template for reporting are available on Github at github.com/viralemergence/comet-standard.

Code availability

No code is used in this manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Colin J. Carlson, Email: colin.carlson@georgetown.edu

Sadie J. Ryan, Email: sjryan@ufl.edu

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-022-01741-4.

References

- 1.Reeves, W. C. Epidemiology and Control of Mosquito-borne Arboviruses in California, 1943–1987. (California Mosquito and Vector Control Association, 1990).

- 2.Tabachnick, W. J. Genetics of Insect Vector Competence for Arboviruses. in Advances in Disease Vector Research (ed. Harris, K. F.) 93–108 (Springer New York, 1994).

- 3.Hardy JL, Houk EJ, Kramer LD, Reeves WC. Intrinsic factors affecting vector competence of mosquitoes for arboviruses. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1983;28:229–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.28.010183.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azar, S. R. & Weaver, S. C. Vector Competence: What Has Zika Virus Taught Us? Viruses11, 867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Poisot, T., Mounce, R. & Gravel, D. Moving toward a sustainable ecological science: don’t let data go to waste! Ideas Ecol. Evol. 6 (2013).

- 6.Rund, S. S. C., Moise, I. K., Beier, J. C. & Martinez, M. E. Rescuing Troves of Hidden Ecological Data to Tackle Emerging Mosquito-Borne Diseases. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association35, 75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Culley TM. The frontier of data discoverability: Why we need to share our data. Appl. Plant Sci. 2017;5:1700111. doi: 10.3732/apps.1700111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibb R, et al. Data Proliferation, Reconciliation, and Synthesis in Viral Ecology. Bioscience. 2021;71:1148–1156. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biab080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renaut S, Budden AE, Gravel D, Poisot T, Peres-Neto P. Management, Archiving, and Sharing for Biologists and the Role of Research Institutions in the Technology-Oriented Age. Bioscience. 2018;68:400–411. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biy038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dallas, T., Carlson, C., Stephens, P., Ryan, S. J. & Onstad, D. insectDisease: programmatic access to the Ecological Database of the World’s Insect Pathogens. Ecography, in press.

- 11.Wilkinson MD, et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data. 2016;3:160018. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkinson MD, et al. A design framework and exemplar metrics for FAIRness. Sci Data. 2018;5:180118. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roche DG, et al. Troubleshooting public data archiving: suggestions to increase participation. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rund SSC, et al. MIReAD, a minimum information standard for reporting arthropod abundance data. Sci Data. 2019;6:40. doi: 10.1038/s41597-019-0042-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards SL, Mores CN, Lord CC, Tabachnick WJ. Impact of extrinsic incubation temperature and virus exposure on vector competence of Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) for West Nile virus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:629–636. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mordecai EA, et al. Thermal biology of mosquito-borne disease. Ecol. Lett. 2019;22:1690–1708. doi: 10.1111/ele.13335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards SL, Anderson SL, Lord CC, Tabachnick WJ. Effects of Virus Dose and Extrinsic Incubation Temperature on Vector Competence of Culex nigripalpus (Diptera: Culicidae) for St. Louis Encephalitis Virus. J. Med. Entomol. 2014;49:1502–1506. doi: 10.1603/ME12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dodson BL, Kramer LD, Rasgon JL. Effects of larval rearing temperature on immature development and West Nile virus vector competence of Culex tarsalis. Parasit. Vectors. 2012;5:199. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kay BH, Fanning ID, Mottram P. Rearing temperature influences flavivirus vector competence of mosquitoes. Med. Vet. Entomol. 1989;3:415–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1989.tb00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christofferson RC, Chisenhall DM, Wearing HJ, Mores CN. Chikungunya viral fitness measures within the vector and subsequent transmission potential. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calvez E, et al. Zika virus outbreak in the Pacific: Vector competence of regional vectors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018;12:e0006637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlson CJ. 2022. viralemergence/comet-standard: Preprint release (v0.1) Zenodo. [DOI]

- 23.Gendernalik A, et al. American Aedes vexans Mosquitoes are Competent Vectors of Zika Virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017;96:1338–1340. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blagrove MSC, et al. Potential for Zika virus transmission by mosquitoes in temperate climates. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2020;287:20200119. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2020.0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holicki CM, et al. German Culex pipiens biotype molestus and Culex torrentium are vector-competent for Usutu virus. Parasit. Vectors. 2020;13:625. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04532-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goddard LB, Roth AE, Reisen WK, Scott TW. Vector competence of California mosquitoes for West Nile virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002;8:1385–1391. doi: 10.3201/eid0812.020536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Souza-Neto JA, Powell JR, Bonizzoni M. Aedes aegypti vector competence studies: A review. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019;67:191–209. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kain, M. P. et al. Not all mosquitoes are created equal: A synthesis of vector competence experiments reinforces virus associations of Australian mosquitoes. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases10.1371/journal.pntd.0010768 (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Albery GF, et al. The science of the host–virus network. Nature Microbiology. 2021;6:1483–1492. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00999-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Carlson CJ. 2022. viralemergence/comet-standard: Preprint release (v0.1) Zenodo. [DOI]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All example data and a blank template for reporting are available on Github at github.com/viralemergence/comet-standard.

No code is used in this manuscript.