Abstract

The efficacy of pneumococcal vaccines in protecting against pneumococcal pneumonia can feasibly be measured only with a diagnostic technique that has a high specificity (0.98 to 1.00) and a sensitivity greatly exceeding that of blood cultures (>0.2 to 0.3). In this context immune-complex enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) offer a novel, convenient diagnostic method, and we have investigated three such assays with appropriate study populations in Kenya. Sera from 129 Kenyan adults with pneumococcal pneumonia and 97 ill controls from the same clinics, but without pneumococcal disease syndromes, were assayed with immune-complex EIAs for pneumolysin, C-polysaccharide, and mixed capsular polysaccharides (Pneumovax II). At an optical density (OD) threshold yielding a specificity of 0.95, the sensitivities (95% confidence intervals) of the assays were 0.22 (0.15 to 0.30), 0.26 (0.19 to 0.34), and 0.22 (0.15 to 0.29), respectively. For pneumolysin immune complexes, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients had a higher mean OD than HIV-negative patients (639 versus 321; P < 0.0001), but stratification by HIV infection status did not alter the performance of this test. Combining the results of all three EIAs did not enhance the diagnostic performances of the individual assays. In Kenyan adults the sensitivities of the immune-complex EIAs could exceed that of blood cultures only at levels of specificity that were insufficient for the performance of vaccine efficacy studies.

In pneumococcal pneumonia, blood cultures have an estimated sensitivity of 0.2 to 0.3, and no diagnostic technique has yet surpassed this figure without significant loss in specificity. Enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) for measurement of antibody responses against pneumolysin, C-polysaccharide, or the capsular polysaccharides in paired sera produced optimistic early results (1, 5), but their poor performance in children and low sensitivity in bacteremic patients prompted the suggestion that the antibodies may be frequently sequestered in immune complexes (IC) (4, 9, 12). An EIA for pneumolysin IC was first developed in 1990 (12). It correctly diagnosed all of 11 bacteremic children and was positive in 47 to 48% of adults and 11 to 51% of children with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) (7, 11, 12; K. S. Lankinen, P. Ruutu, H. Nohynek, M. Lucero, J. Paton, and M. Leinonen, Program Abstr. 1st Int. Symp. Pneumococci Pneumococcal Dis., p. 83, 1998). The assay has several advantages: it is not restricted by serotype; it is rapid, producing results within 24 h; sera can be screened at a single dilution, facilitating high throughput; and the majority of patients with pneumolysin IC are positive at presentation (12).

Studies of vaccine efficacy with a pneumococcal pneumonia end point are of prohibitive size and cost because of the insensitivity of blood culture diagnosis. For this purpose a more sensitive diagnostic technique is clearly attractive, and two recently published studies of polysaccharide vaccine efficacy have incorporated the pneumolysin IC-EIA into their case definition and relied on it alone for up to 82% of the diagnoses of pneumococcal pneumonia. In neither study was the vaccine found to protect against pneumococcal pneumonia (8, 14). We were interested in using an IC-EIA in epidemiological studies of pneumococcal pneumonia in Kenyan adults, and therefore we tested for the presence of pneumococcus-specific IC containing pneumolysin, C-polysaccharide, or capsular polysaccharides in populations of sufficient size to estimate sensitivity and specificity with precision.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All subjects were ≥15 years old, were attending one of two hospitals in Kilifi or Mombasa on the coast of Kenya, and gave written informed consent to the study. Sensitivity was estimated for the 129 of 301 consecutive cases of acute CAP who met all of the following criteria: (i) a history of respiratory illness of ≤2 weeks in duration, (ii) pulmonary consolidation on the chest radiograph, and (iii) isolation of Streptococcus pneumoniae from blood or lung aspirate cultures or detection in urine of pneumococcal capsular antigen of serogroup 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 12, 14, 19, or 22 by using a serotype/group-specific latex agglutination assay. This antigen assay had a specificity of 0.98 when validated in a similar population (17). The specificities of the IC-EIAs were estimated with 97 controls randomly selected from patients attending the same clinics as the pneumonia patients. Those with a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia, meningitis, septicemia, or upper respiratory tract infection were ineligible. Exposure to pneumococcal vaccine is extremely uncommon in this population.

IC were precipitated from serum by mixing with 7% polyethylene glycol in sodium borate (0.1 mol/liter) at 4°C overnight (12). The precipitate was retrieved by centrifugation at 8,320 × g for 30 min at 4°C, washed twice in 3.5% polyethylene glycol, and finally resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (0.01 M). Microtiter plates (Maxisorb; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were incubated overnight at 37°C with either pneumolysin, C-polysaccharide (Statens Seruminstitut, Copenhagen, Denmark), or a mixture of 23 capsular polysaccharides (Pneumovax II). Pneumolysin was obtained, courtesy of M. Sarvas (Helsinki, Finland), by recombination and expression of the pneumolysin gene in Bacillus subtilis (19). The pneumolysin assay was also repeated with recombinant pneumolysin derived from Escherichia coli, courtesy of J. Paton (Adelaide, Australia) (15).

Plates were postcoated for 1 h with 10% fetal calf serum and incubated for 2 h with IC, in duplicate, at a single dilution of 1:100 and for 2 h with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (12). Each step was preceded by four washes with 0.05% Tween in phosphate-buffered saline. After incubation with p-nitrophenylphosphate, the reaction was read photometrically at 405 nm. Each plate included a high-reactivity control, comprising IC artificially constructed from purified antigen (B. subtilis pneumolysin, C-polysaccharide, or Pneumovax II) and pooled human immunoglobulin (Sandoglobulin, Sandoz, Switzerland), and a low-reactivity control, consisting of pooled sera from healthy volunteers.

RESULTS

The mean ages of the pneumococcal pneumonia patients and controls were 32 and 35 years, and the percentages of males in each group were 67 and 51%, respectively. Half of the pneumococcal pneumonia group and 31% of the control group were human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive. Each control provided one serum sample. Each of the 129 pneumococcal pneumonia patients was sampled on admission, a median of 6 days after the onset of illness. Most pneumococcal pneumonia patients were also sampled at discharge (n = 89), a median of 5 days after admission, and at a follow-up appointment (n = 102), a median of 27 days after admission. Every sample was assayed, but only the highest value for each subject was used in the analysis. For the pneumolysin IC assay the maximum value was obtained from the acute-phase serum in 41 patients (32%), from the discharge serum in 47 patients (36%), and from the follow-up serum in 41 patients (32%). The optical density (OD) result for each serum was standardized from plate to plate by using the formula OD = a × m/c, where a is the mean OD of the test serum duplicates, m is the mean OD for the high-reactivity control throughout the whole assay, and c is the OD for the high-reactivity control on the plate being read. For each assay, the distribution of these standardized ODs was log normal. The coefficient of variation of the pneumolysin IC-EIA, estimated with one sample run 19 times, was 9.2%.

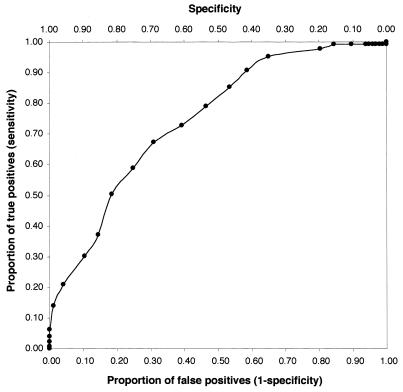

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed from estimates at each 0.1-U increase in log OD. The curve for the pneumolysin IC-EIA is shown in Fig. 1. In addition, sensitivity estimates were maximized by selecting the lowest OD threshold that would yield specificity at a fixed level. At a specificity of 0.99, the sensitivity estimates for the IC-EIAs for pneumolysin, C-polysaccharide, and mixed capsular polysaccharide antigens were 0.17, 0.14, and 0.12, respectively; the results at specificity criteria of 0.95 and 0.90 are shown in Table 1. Restricting the sensitivity analysis to 74 patients who had positive blood or lung aspirate cultures did not alter the performance of the three tests (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

ROC curve for the pneumolysin IC-EIA.

TABLE 1.

Sensitivity estimates for pneumolysin, C-polysaccharide, and capsular polysaccharide IC-EIAs, using OD thresholds to fix specificity

| IC-EIA | Patients | No. of cases assayed | Specificity set at 0.90

|

Specificity set at 0.95

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std ODa | Sensitivity | 95% CIb | Std OD | Sensitivity | 95% CI | |||

| B. subtilis pneumolysin | All | 129 | 782 | 0.30 | 0.22–0.38 | 922 | 0.22 | 0.15–0.30 |

| Culture positive | 74 | 782 | 0.32 | 0.22–0.43 | 922 | 0.23 | 0.13–0.33 | |

| HIV positivec | 64 | 1,004 | 0.31 | 0.20–0.43 | 1,203 | 0.27 | 0.16–0.37 | |

| HIV negativec | 65 | 416 | 0.46 | 0.34–0.58 | 711 | 0.17 | 0.08–0.26 | |

| Malec | 87 | 700 | 0.37 | 0.27–0.47 | 907 | 0.26 | 0.17–0.36 | |

| E. coli pneumolysin | All | 126 | 1,311 | 0.29 | 0.21–0.37 | 1,700 | 0.18 | 0.11–0.24 |

| Culture positive | 72 | 1,311 | 0.33 | 0.22–0.44 | 1,700 | 0.21 | 0.11–0.30 | |

| C-polysaccharide | All | 129 | 498 | 0.42 | 0.33–0.50 | 673 | 0.26 | 0.19–0.34 |

| Culture positive | 74 | 498 | 0.34 | 0.23–0.45 | 673 | 0.28 | 0.18–0.39 | |

| Capsular polysaccharide | All | 129 | 417 | 0.31 | 0.23–0.39 | 710 | 0.22 | 0.15–0.29 |

| Culture positive | 74 | 417 | 0.30 | 0.19–0.40 | 710 | 0.22 | 0.12–0.31 | |

Std, standardized on the value of the high-reactivity control (see Results).

CI, confidence interval.

The OD thresholds vary for these groups because the control group also was restricted by the appropriate factor.

To examine whether the poor detection characteristics of the pneumolysin IC-EIA were restricted to B. subtilis-derived antigen, the assay was repeated with E. coli-derived antigen for 95 of the controls and 126 of the cases of pneumococcal pneumonia. The correlation between the two assays was good (r = 0.85), and the detection characteristics with E. coli pneumolysin were indistinguishable from those with B. subtilis pneumolysin (Table 1).

The pneumolysin IC-EIA results varied significantly with HIV infection status. Among pneumococcal pneumonia patients, the geometric mean OD was 639 for HIV-positive patients and 321 for HIV-negative patients (P < 0.0001); for the negative controls, the results were 356 and 129 respectively (P < 0.0001). However, stratification of the analysis by HIV infection status did not significantly alter the sensitivity estimates obtained at the fixed specificity thresholds (Table 1). Males were overrepresented in the pneumococcal pneumonia patient group, but restriction to male sex did not alter the sensitivity either (Table 1).

To explore whether a subgroup of the control population was responsible for the poor detection characteristics of the pneumolysin IC-EIA, the subjects were grouped by clinical diagnosis. The effect upon specificity of eliminating any 1 of 14 diagnostic groups from the analysis was estimated for each group in turn at a fixed sensitivity of 0.50 (Table 2). The specificity estimates varied within a narrow range (0.80 to 0.86), being greatest after elimination of patients with gastroenteritis, among whom HIV-seropositive patients were strongly represented (13 of 17).

TABLE 2.

Effect of elimination of diagnostic groups on specificity of the pneumolysin IC-EIA

| Diagnostic group | No. of patients | Assay specificity after exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Gastroenteritis | 17 | 0.86 |

| Miscellaneous | 11 | 0.81 |

| Urinary tract infection | 11 | 0.80 |

| Heart failure | 7 | 0.80 |

| Minor surgery | 7 | 0.80 |

| Asthma | 6 | 0.81 |

| Epigastric pain | 6 | 0.82 |

| Anemia | 5 | 0.82 |

| Dermatitis | 5 | 0.82 |

| Malaria | 5 | 0.80 |

| Gynecological | 5 | 0.82 |

| Trauma | 5 | 0.82 |

| Back pain | 4 | 0.82 |

| Jaundice | 3 | 0.81 |

| All patients | 97 | 0.81 |

The ROC curves for the C-polysaccharide IC-EIA and the capsular polysaccharide IC-EIA were similar to those for the pneumolysin IC-EIA, as were the maximized sensitivity estimates at fixed specificity thresholds (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Epidemiological investigations, and particularly vaccine efficacy studies, require a diagnostic case definition with an extremely high specificity, in the region of 0.98 to 1.00. Misclassification of true negatives as positive cases dilutes the association between unvaccinated status and disease, leading to an artificially low point estimate of vaccine efficacy with a broader variance estimate. With only a modest reduction in specificity it is possible to observe a null result in the study of a highly efficacious vaccine. It is critically important to evaluate the specificity of the case-defining techniques prior to their inclusion in a study. We have evaluated IC-EIAs by using pneumolysin, C-polysaccharide, and capsular polysaccharide antigens and found that the OD thresholds required to exceed the sensitivity of blood cultures in the diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia yielded specificity estimates of <0.90.

In previous studies of the pneumolysin IC-EIA, OD thresholds have been determined by sampling normal healthy children to set a specificity of 0.93 to 1.00, and this has produced a useful number of diagnoses in studies of CAP (11, 12; Lankinen et al., 1st Int. Symp. Pneumococci Pneumococcal Dis.). For adults, published specificity estimates have also been derived only from populations of healthy subjects (12, 13). In choosing a negative control group, we must strike a balance between two competing requirements: the need to stress the assay with sera from sick individuals and the need to exclude all cases of pneumococcal disease. Sera from acutely ill patients can give rise to nonspecific positivity in serological assays. For example, in 1968 Sutliff and Zoffuto (18) set a threshold for their pneumolysin antibody neutralization test that excluded 24 of 25 normal healthy controls (i.e., specificity = 0.96). This correctly diagnosed half of 48 pneumococcal pneumonia patients, but when applied to a control population of 62 medical admissions without fever or pneumonia, it produced a specificity of only 0.73 (18). As the test will be applied only to sick individuals, the selection of normal healthy controls tends to overestimate specificity. If we select controls who are not healthy, however, it is important to ensure that their illnesses are not due to pneumococcal disease; otherwise, the specificity of the assay will be underestimated. In practice, it is impossible to exclude cases of pneumococcal disease by using laboratory diagnostic tests because they have such low sensitivities. Blood cultures fail to diagnose 70 to 80% of patients with pneumococcal pneumonia, and the urine antigen assay used here misses more than half of all cases (17). For these reasons we recruited sick individuals to our negative control group but attempted to exclude patients with pneumococcal disease on broad clinical criteria.

The prevalence of HIV in our controls was high, and as pneumococcal disease may have unusual manifestations in HIV-positive subjects (16), there is a possibility that the poor specificity we observed could be due to inadvertent inclusion of atypical pneumococcal cases in the negative control group. However, if the true sensitivity and specificity of the pneumolysin IC-EIA were 0.50 and 0.98, respectively, we would have to postulate that as many as 17% of the controls were occult pneumococcal cases to obtain concordance with the observed results, and this seems most improbable.

The serological differentiation of populations with and without pneumococcal disease may be hampered by cross-reactivity in human sera, although the identity of potential cross-reactive antigens is not immediately obvious. Pneumolysin resembles other cytolytic, gram-positive proteins, including streptolysin O, perfringolysin, tetanolysin, cereolysin, and listeriolysin (6, 20), but previous studies of anti-streptolysin O and antipneumolysin antibodies have revealed little correlation (6). Recombinant pneumolysin might also contain natural antigen from the vector organisms, although again there is little evidence indicating a cross-reactive effect; antibody EIA results with B. subtilis pneumolysin have been shown to be comparable to those obtained with natural antigen in Finnish subjects (4), and the use of E. coli, to which human antibodies are widespread (3), as a vector did not produce a significant decrease in the detection characteristics of the assay in our hands.

An alternative explanation of the disappointing results reported here is that transient, intermittent, subclinical pneumococcal bacteremia may lead to detectable concentrations of immune complexes in serum. This idea receives support from the demonstration of pneumolysin gene fragments in the blood of normal healthy children in Israel by PCR (2). If adults also experience transient pneumococcal bacteremia, this could give rise to false-positive results with the IC-EIAs, particularly in the tropics, where exposure to S. pneumoniae is thought to be higher than it is elsewhere.

The insensitivity of individual serological tests might be overcome by combining a number of tests into a single protocol (10), but it is important to remember to apply the same protocol to the negative control group as well. Using the OD thresholds that yielded a specificity of 0.90 in each of the three different antigen assays, we assessed the detection characteristics of two combination case definitions. Protocol A was defined by a single positive result on any one of the IC-EIAs, i.e., that for pneumolysin, C-polysaccharide, or capsular polysaccharides. Protocol B was defined by positivity on all three of the different IC-EIAs. Sensitivity was marginally improved by protocol A (0.45) but with significant loss in overall specificity (0.82). Specificity was improved by protocol B (0.96) but with significant loss in sensitivity (0.16). Combining diagnostic tests is likely to improve diagnosis only if the specificities of the individual tests are very high and the results of the different assays are not highly correlated. Similarly, repetition of the serological tests with several sera per patient, as undertaken in our study, should ideally be reproduced in the control group to measure the accumulation of false-positive results with each repetition. As we did not do this, our results may actually overestimate the performance of these tests.

The assay of IC to common pneumococcal antigens is an innovative response to a difficult diagnostic problem, but unfortunately it has not differentiated cases from controls sufficiently well to prove clinically useful in Kenya. Variations in the methodology, e.g., assaying sera at several dilutions or including a dissociation step, might improve the detection characteristics, although they would detract from the simplicity of the assay described. In a temperature climate, where the prevalence of carriage and the incidence of transient pneumococcal invasion are thought to be lower than they are in Kenya, the tests may perform significantly better than reported here, but they have yet to be validated with an appropriate control group. For Kenyan adults, the IC-EIAs could surpass the sensitivity of blood cultures only at levels of specificity that were insufficient for the performance of analytical epidemiological investigations or vaccine efficacy studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported by KEMRI and the Wellcome Trust of Great Britain. J.A.G.S. was supported by a Wellcome Trust research training fellowship in clinical epidemiology (035375).

We thank Justin Gulani and Christopher Chigiri for collecting the serum specimens and Anu Ojala for repeating the pneumolysin IC-EIA with E. coli-derived antigen.

Footnotes

This paper is published with the permission of the director of KEMRI.

REFERENCES

- 1.Claesson B A, Trollfors B, Brolin I, Granstrom M, Henrichsen J, Jodal U, Juto P, Kallings I, Kanclerski K, Lagergard T, Steinwall L, Strannegard O. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in children based on antibody responses to bacterial and viral antigens. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8:856–862. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198912000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dagan R, Shriker O, Hazan I, Leibovitz E, Greenberg D, Schlaeffer F, Levy R. Prospective study to determine clinical relevance of detection of pneumococcal DNA in sera of children by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:669–673. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.669-673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffiths E, Stevenson P, Thorpe R, Chart H. Naturally occurring antibodies in human sera that react with the iron-regulated outer membrane proteins of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1985;47:808–813. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.3.808-813.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jalonen E, Taira S, Paton J C, Kerttula Y, Suomalainen P, Leinonen M. Pneumolysin produced by Bacillus subtilis as antigen for measurement of pneumococcal antibodies by enzyme immunoassay. Serodiagn Immunother Infect Dis. 1990;4:459–468. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanclerski K, Blomquist S, Granstrom M, Mollby R. Serum antibodies to pneumolysin in patients with pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:96–100. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.1.96-100.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanclerski K, Granstrom M, Mollby R. Immunological relation between serum antibodies against pneumolysin and against streptolysin O. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand Sect B. 1987;95:241–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1987.tb03119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kauppinen M T, Herva E, Kujala P, Leinonen M, Saikku P, Syrjala H. The etiology of community-acquired pneumonia among hospitalized patients during a Chlamydia pneumoniae epidemic in Finland. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1330–1335. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.5.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koivula I, Sten M, Leinonen M, Makela P H. Clinical efficacy of pneumococcal vaccine in the elderly: a randomized, single-blind population-based trial. Am J Med. 1997;103:281–290. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korppi M, Heiskanen K T, Jalonen E, Saikku P, Leinonen M, Halonen P, Makela P H. Aetiology of community-acquired pneumonia in children treated in hospital. Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152:24–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02072512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korppi M, Koskela M, Jalonen E, Leinonen M. Serologically indicated pneumococcal respiratory infection in children. Scand J Infect Dis. 1992;24:437–443. doi: 10.3109/00365549209052629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korppi M, Leinonen M. Pneumococcal pneumonia in children; new data from circulating immune complexes. Eur J Pediatr. 1997;156:341–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leinonen M, Syrjälä H, Jalonen E, Kujala P, Herva E. Demonstration of pneumolysin antibodies in circulating immune complexes—a new diagnostic method for pneumococcal pneumonia. Serodiagn Immunother Infect Dis. 1990;4:451–458. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lieberman D, Schlaeffer F, Boldur I, Lieberman D, Horowitz S, Friedman M G, Leinonen M, Horovitz O, Manor E, Porath A. Multiple pathogens in adult patients admitted with community-acquired pneumonia: a one year prospective study of 346 consecutive patients. Thorax. 1996;51:179–184. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortqvist A, Hedlund J, Burman L-A, Elbel E, Hofer M, Leinonen M, Lindblad I, Sundelof B, Kalin M the Swedish Pneumococcal Vaccine Study Group. Randomised trial of 23-valent pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide vaccine in prevention of pneumonia in middle-aged and elderly people. Lancet. 1998;351:399–403. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07358-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paton J C, Lock R A, Hansman D J. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the Streptococcus pneumoniae gene encoding pneumolysin. Infect Immun. 1986;54:50–55. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.1.50-55.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez Barradas M C, Musher D M, Hamill R J, Dowell M, Bagwell J T, Sanders C V. Unusual manifestations of pneumococcal infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals: the past revisited. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:192–199. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott J A G, Hannington A, Marsh K, Hall A J. Diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia in epidemiological studies: evaluation in Kenyan adults of a serotype-specific urine latex agglutination assay. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:764–769. doi: 10.1086/515198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutliff W D, Zoffuto A. Pneumolysin and antipneumolysin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1968;8:350–352. doi: 10.1128/AAC.8.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taira S, Jalonen E, Paton J C, Sarvas M, Runeberg-Nyman K. Production of pneumolysin, a pneumococcal protein toxin, in Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1989;77:211–218. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tweten R K. Nucleotide sequence of the gene for perfringolysin O (theta-toxin) from Clostridium perfringens: significant homology with the genes for streptolysin O and pneumolysin. Infect Immun. 1988;56:3235–3240. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.12.3235-3240.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]