Abstract

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) presents with symptoms early in life and the disease course may be progressive, but longitudinal data on lung function are scarce. This multinational cohort study describes lung function trajectories in children, adolescents and young adults with PCD. We analysed data from 486 patients with repeated lung function measurements obtained between the age of 6 and 24 years from the International PCD Cohort and calculated z-scores for forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and FEV1/FVC ratio using the Global Lung Function Initiative 2012 references. We described baseline lung function and change of lung function over time and described their associations with possible determinants in mixed-effects linear regression models. Overall, FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC z-scores declined over time (average crude annual FEV1 decline was −0.07 z-scores), but not at the same rate for all patients. FEV1 z-scores improved over time in 21% of patients, remained stable in 40% and declined in 39%. Low body mass index was associated with poor baseline lung function and with further decline. Results differed by country and ultrastructural defect, but we found no evidence of differences by sex, calendar year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, diagnostic certainty or laterality defect. Our study shows that on average lung function in PCD declines throughout the entire period of lung growth, from childhood to young adult age, even among patients treated in specialised centres. It is essential to develop strategies to reverse this tendency and improve prognosis.

Short abstract

Lung function in children with PCD is reduced by the age of 6 years and further declines during the growth period. It is essential to develop strategies to improve prognosis. https://bit.ly/34EBekm

Introduction

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) commonly leads to chronic upper and lower airway disease due to impaired mucociliary clearance. Clinical course is variable, but many patients present with neonatal respiratory distress, develop bronchiectasis at preschool age, and some progress to end-stage lung disease with respiratory failure and transplantation in adulthood [1–6]. In a systematic review covering the period 1980 to 2017, we identified 24 small studies on lung function in patients with PCD [7]. 12 studies had longitudinal lung function data, mostly from adult patients. Among these, four studies reported that lung function remained stable over time and four concluded that it deteriorated. The largest study reported that FEV1 improved over time in 10% of Danish patients, remained stable in 57% and declined in 34% [8]. Models of lung function changes over a lifetime distinguish between lung function at birth, lung growth during childhood, a short plateau phase and the long period of lung function decline [9, 10]. The pattern of lung function growth in early years determines lung function later in life, and also life expectancy [11, 12]. Combining patients of different ages in one model does not allow to disentangle these phases and identify possible risk factors. For people with PCD, only two studies focused on lung function growth during childhood [13, 14]. One, with 137 children from specialised PCD clinics in North America, found a variable time course with ultrastructural defects highlighted as the main determinant of heterogeneity [13]. The second, with 158 children from three countries, reported variable lung function trajectories during childhood but no difference between centres [14].

We have previously presented cross-sectional lung function data from the International PCD (iPCD) Cohort study and showed that forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) were reduced compared to Global Lung Function Initiative 2012 (GLI) reference values in patients of all ages [15]. The design of that study did not permit investigation of lung function changes over time, nor did it allow to identify factors that influence lung function trajectories.

The present study describes lung function trajectories in an international cohort of children and young adults with PCD from age 6 to 24 years. We compared FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC ratio of study participants with the GLI reference values at baseline and investigated changes in lung function over time, i.e. whether z-scores improved, remained stable or decreased. Second, we investigated a range of potential determinants for their association with lung function at baseline or with subsequent change of lung function over time.

Methods

Study design and study population

The iPCD Cohort is a large international dataset of patients with PCD set up during the European Union Seventh Framework Programme project Better Experimental Screening and Treatment for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (BESTCILIA) and expanded during COST-Action BEAT-PCD [16, 17]. The current analysis includes data from patients aged 6 to 24 years with multiple measurements on FEV1 and FVC that were delivered by March 2019. Data came from routine follow-up in PCD clinics and were extracted from hospital records or exported from regional or national PCD registries [17]. The minimal required number of lung function measurements was one per year per patient, and for this analysis we only included patients for whom at least three lung function measurements had been recorded. When necessary, principal investigators obtained ethics approval and informed consent or assent in their countries to contribute observational pseudonymised data.

PCD diagnosis

PCD diagnosis remains challenging and has evolved over the years [18]. Guidelines recommend a combination of tests [19], but test availability differs between countries and centres and has changed over time [20, 21]. Therefore, not all iPCD patients were diagnosed according to current recommendations. We accounted for this by distinguishing three levels of diagnostic certainty: patients with definite PCD according to the European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines [19] with a hallmark ultrastructural defect identified by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) or pathogenic biallelic PCD genetic mutations; patients with probable PCD who had abnormal high-speed video microscopy findings or low nasal nitric oxide; and patients diagnosed on clinical grounds with an incomplete diagnostic algorithm. All patients had a clinical phenotype consistent with PCD, and other diagnoses had been excluded.

Lung function and microbiology

Lung function measurements were performed at each centre according to ERS/American Thoracic Society guidelines. All centres provided FEV1 and FVC measurements recorded before any use of inhaled bronchodilators. Spirometry quality assessment was performed locally at the clinics. Cleaning of data was performed after pooling data from all centres and included checking for outliers, implausible values or missing data, for which we contacted each centre to check the records. We standardised the lung function measurements by calculating FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC z-scores adjusted for age, sex, height and ethnicity using the GLI 2012 reference values [22]. Baseline FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC values were defined as the individuals’ first available measurement, and measurements done before the age of 6 years were excluded to improve comparability. We asked local principal investigators to only include measurements from scheduled follow-up visits where patients were in a stable condition, defined as not having an acute infection. Sputum microbiology data were collected from the medical charts at the same time point as lung function was measured. We collected data about the five most common isolated pathogens including Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis.

Potential determinants of lung function and of lung function trajectories

We investigated associations of potential determinants on lung function by differentiating between effects on baseline lung function (the intercept) and effects on change of lung function over time (the slope). We included factors that had been described previously to affect lung function and were available from all centres: country of residence, sex, age at diagnosis of PCD, year of diagnosis, level of diagnostic certainty, organ laterality, age, body mass index (BMI) z-scores based on World Health Organization reference values [23] at first lung function testing and ultrastructural defect. Ultrastructural defects were grouped as in recent publications [13, 24] into: 1) normal TEM results; 2) outer dynein arm (ODA) defect; 3) outer and inner dynein arm (IDA) defects; 4) microtubular disorganisation defects, consisting of nexin link defects combined with IDA or tubular disorganisation defects combined with IDA; 5) central complex defects, defined as central pair defects or tubular transposition defects; or 6) any other defect (i.e. isolated IDA, acilia or nexin link defects and tubular disorganisation without IDA). Group 6 (any other defects) was excluded from the analysis. All determinants except age were time-independent.

Statistical analysis

In case of missing data, we contacted principal investigators. If the missing data could not be retrieved, the record was excluded from analysis. For laterality defects, we coded patients with missing information as “situs not reported”. Ultrastructural defects and sputum microbiology had not been assessed in all patients, and therefore we investigated these factors in a subgroup analysis.

We studied whether FEV1 z-scores improved, remained stable or decreased by computing average yearly trajectories using linear regression for each patient separately including the repeated lung function measurements and age. We classified individual FEV1 trajectories based on the natural variability of lung function in healthy children into three groups: those who improved over time (>0.05 z-scores per year), remained stable (≤0.05 and ≥ −0.05 z-scores per year) and decreased (< −0.05 z-scores per year) [25].

We compared z-scores of FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC with the GLI reference values [22], and investigated associations of baseline lung function and lung function trajectories with potential determinants in multivariable linear mixed effects regression models with a random intercept at the patient level. We tested for linearity of mean trajectory by including age as a linear and quadratic term and computed the p-value for the coefficient of the quadratic term. In addition, we included a random slope to allow for individual differences in lung function change by age. To assess whether changes in FEV1 or FVC z-scores over time were modified by certain patient characteristics, we included interaction terms between age at lung function test and the potential determinants considered. We also tested for a possible interaction between age at diagnosis and country. We used likelihood ratio tests to calculate p-values for single variables and for interaction terms. For categorical variables, the largest group was chosen as reference category. We tested robustness of the parameter estimates across countries by running the regression model for single countries with >30 patients. We ran a sensitivity analysis excluding patients who were diagnosed the same year as the first lung function measurement was performed to investigate if baseline lung function and change in lung function over time could be affected by initiation of PCD-specific treatment after diagnosis. We investigated the effects of ultrastructural defects on lung function growth in a subgroup of children with available TEM results. Adjusting for the same determinants as before, we included an interaction term between type of ultrastructural defect and age to assess whether lung function changes over time differed between ultrastructural defects.

To assess the amount of variance explained by all the predictors in our model we calculated in this subgroup the marginal R2, i.e. the proportion of variance explained by the fixed factors, and conditional R2, i.e. the proportion of variance explained by both the fixed and random factors, using the method by Nakagawa et al. [26]. We then compared R2 of the models with and without addition of ultrastructural defects. All analyses were performed using R 3.5.1 (www.r-project.org), linear mixed models with the R-package lme4.

Results

Population characteristics

By March 2019, 20 centres had delivered cleaned and standardised longitudinal data for 4470 lung function tests from 486 individuals (supplementary figure S1). In 130 patients, the first lung function test stemmed from the year PCD was diagnosed, in the others it was later, often because PCD had been diagnosed at preschool age. The largest datasets came from Germany (60 patients), Denmark (59 patients), Turkey (49 patients) and Israel (41 patients) (table 1). Half (49%) of the patients were female; mean age at diagnosis was 8.6 years; 17% had been diagnosed before 1999, 38% between 1999 and 2008 and 45% after 2009. The PCD diagnosis was classified as definite in 65%, probable in 28% and clinical in 7% of patients. Half (52%) of the patients had situs solitus, 37% situs inversus, 3% heterotaxia and 8% unknown situs. Information on ultrastructural defects was available for 366 (75%) patients. Dynein arm defects were identified in 213 patients; a central complex defect in 40; and microtubular disorganisation in 28. Information on microbiology was available for 250 patients with 1609 samples. In 90% of the samples at least one pathogen was isolated. The most common isolated pathogen was H. influenza, found in 74% of patients and 41% of samples, followed by S. pneumoniae (35% of patients, 12% of all samples), Staph. aureus (33% of patients, 10% of samples), P. aeruginosa (24% of patients, 8% of samples) and M. catarrhalis (18% of patients, 7% of samples). The prevalence of isolated pathogens differed by age group (supplementary figure S2). Mean age at the first lung function test was 11 years; mean±sd BMI z-score −0.04±1.27.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) (n=486)

| All included patients | Patients with information about ultrastructural defects | |||

| Patients | Measurements | Patients | Measurements | |

| Patients n | 486 | 366 | ||

| Country | ||||

| Australia | 16 (3) | 126 (3) | 15 (4) | 118 (3) |

| Belgium | 14 (3) | 151 (3) | 14 (4) | 151 (4) |

| Cyprus | 15 (3) | 145 (3) | 15 (4) | 145 (4) |

| Czech Republic | 27 (5) | 136 (3) | 27 (7) | 136 (4) |

| Denmark | 59 (12) | 1459 (33) | 47 (13) | 1063 (31) |

| France | 38 (8) | 340 (8) | 31 (8) | 297 (9) |

| Germany | 60 (12) | 664 (15) | 44 (12) | 503 (15) |

| Greece | 3 (1) | 16 (0) | ||

| Israel | 41 (8) | 239 (5) | 33 (9) | 199 (6) |

| Italy | 32 (7) | 163 (4) | 32 (9) | 163 (5) |

| The Netherlands | 38 (8) | 114 (3) | 22 (6) | 66 (2) |

| Norway | 13 (3) | 82 (2) | 13 (4) | 82 (2) |

| Poland | 21 (4) | 75 (2) | 14 (4) | 49 (1) |

| Switzerland | 23 (5) | 264 (6) | 20 (5) | 225 (7) |

| Turkey | 49 (10) | 329 (7) | 10 (3) | 95 (3) |

| UK | 37 (8) | 167 (4) | 29 (8) | 128 (4) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 247 (51) | 2192 (49) | 192 (52) | 1711 (50) |

| Female | 239 (49) | 2278 (51) | 174 (48) | 1709 (50) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 8.64±6.1 | 8.33±6.2 | ||

| Time period of diagnosis | ||||

| 1978–1998 | 85 (17) | 1345 (30) | 75 (21) | 1139 (33) |

| 1999–2008 | 184 (38) | 1793 (40) | 150 (41) | 1372 (40) |

| 2009–2018 | 217 (45) | 1332 (30) | 141 (38) | 909 (27) |

| Diagnostic certainty | ||||

| Definite PCD diagnosis# | 318 (65) | 2933 (66) | 317 (87) | 2924 (85) |

| Probable PCD diagnosis¶ | 137 (28) | 1309 (29) | 40 (11) | 402 (12) |

| Clinical diagnosis only | 31 (7) | 228 (5) | 9 (2) | 94 (3) |

| Organ laterality | ||||

| Situs solitus | 254 (52) | 2424 (54) | 191 (52) | 1861 (54) |

| Situs inversus | 182 (37) | 1613 (36) | 139 (38) | 1191 (35) |

| Heterotaxia | 12 (3) | 99 (2) | 10 (3) | 93 (3) |

| Situs status not reported | 38 (8) | 334 (8) | 26 (7) | 275 (8) |

| Ultrastructural defect | ||||

| Normal | 48 (10) | 439 (10) | 48 (13) | 439 (13) |

| Central complex | 40 (8) | 452 (10) | 40 (11) | 452 (13) |

| ODA | 112 (23) | 1019 (23) | 112 (31) | 1019 (30) |

| ODA/IDA | 101 (21) | 859 (19) | 101 (28) | 859 (25) |

| Microtubular disorganisation | 28 (6) | 286 (6) | 28 (7) | 286 (8) |

| Other | 37 (7) | 365 (8) | 37 (10) | 365 (11) |

| No information | 120 (25) | 1050 (24) | ||

| Values at first measure | ||||

| Age (years) | 10.94±4.35 | 10.52±4.28 | ||

| BMI z-scores | −0.04±1.27 | −0.01±1.25 | ||

| FEV1 z-scores | −1.22±1.62 | −1.1±1.61 | ||

| FVC z-scores | −0.74±1.71 | −0.6±1.66 | ||

| FEV1/FVC z-scores | −0.91±1.44 | −0.9±1.46 | ||

| Values at last measure | ||||

| Age (years) | 16.29±4.84 | 16.39±5.03 | ||

| BMI z-scores | 0.01±1.21 | 0.03±1.21 | ||

| FEV1 z-scores | −1.51±1.56 | −1.45±1.59 | ||

| FVC z-scores | −0.71±1.58 | −0.65±1.61 | ||

| FEV1/FVC z-scores | −1.43±1.31 | −1.40±1.32 | ||

Data are presented as n (%) or mean±sd. ODA: outer dynein arm; IDA: inner dynein arm; BMI: body mass index; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s: FVC: forced vital capacity. #: defined as hallmark PCD ultrastructural defect identified by electron microscopy findings or biallelic PCD causing gene mutation based on the European Respiratory Society PCD diagnosis guidelines [19]; ¶: abnormal light or high-frequency video microscopy finding and/or low (≤77 nL·min−1) nasal nitric oxide value.

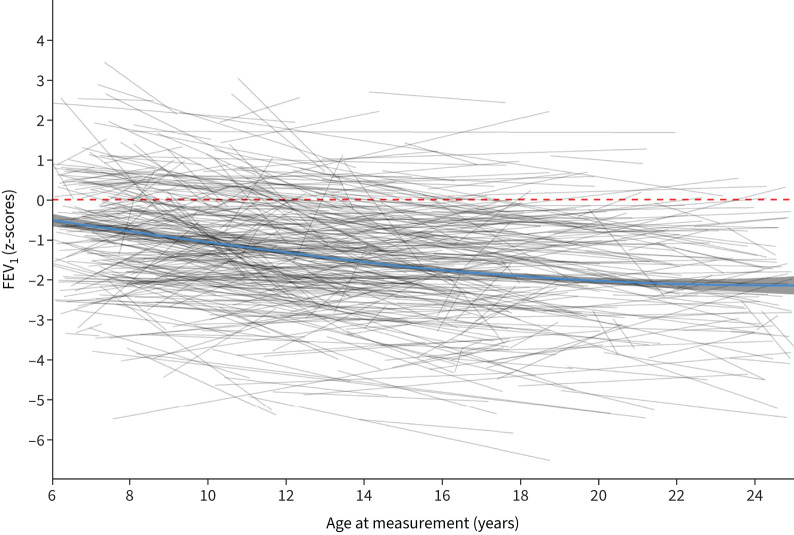

Lung function

Median (interquartile range (IQR)) number of lung function tests per participant was 6 (4–11) and median (IQR) follow-up time 4.14 (2.3–7.6) years. Lung function was below average already at baseline, with a mean±sd FEV1 z-score −1.22±1.62, FVC z-score −0.74±1.71 and FEV1/FVC −0.91±1.44 (table 1, figure 1 and supplementary figure S3). At the last test, mean±sd FEV1 z-score was −1.51±1.56, FVC z-score was −0.71±1.58 and FEV1/FVC was −1.43±1.31. Average individual annual change in FEV1 was −0.06 z-scores (95% CI −0.072 to −0.057), −0.03 z-scores (95% CI −0.040 to −0.023) for FVC and −0.062 z-scores (95% CI −0.070 to −0.054) for FEV1/FVC. Lung function slopes differed between individuals: average yearly FEV1 improved by ≥0.05 z-scores in 21% of patients, remained stable in 40% and decreased in 39% (table 2). Results from the regression analysis comparing FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC z-scores with GLI reference scores showed no evidence of a nonlinear trend in lung function decline (table 3, supplementary tables S1 and S2).

FIGURE 1.

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) trajectories during the lung growth period compared to Global Lung Function Initiative 2012 reference values.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) from the international PCD cohort by forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) trajectories (lung function improving, stable or decreasing over time) (n=486)

| Lung function trajectories # | |||

| Improving | Stable | Decreasing | |

| Total | 99 (21) | 196 (40) | 191 (39) |

| Country | |||

| Australia | 3 (19) | 5 (31) | 8 (50) |

| Belgium | 2 (14) | 6 (43) | 6 (43) |

| Cyprus | 3 (20) | 9 (60) | 3 (20) |

| Czech Republic | 6 (22) | 13 (48) | 8 (30) |

| Denmark | 7 (12) | 26 (44) | 26 (44) |

| France | 5 (13) | 9 (24) | 24 (63) |

| Germany | 14 (23) | 21 (35) | 25 (42) |

| Greece | 2 (66) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) |

| Israel | 6 (15) | 18 (44) | 17 (41) |

| Italy | 6 (19) | 14 (44) | 12 (37) |

| The Netherlands | 5 (13) | 16 (42) | 17 (45) |

| Norway | 2 (15) | 5 (38) | 6 (46) |

| Poland | 6 (29) | 9 (42) | 6 (29) |

| Switzerland | 3 (13) | 11 (48) | 9 (39) |

| Turkey | 21 (43) | 16 (33) | 12 (24) |

| UK | 10 (27) | 16 (43) | 11 (30) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 49 (21) | 98 (41) | 92 (38) |

| Female | 50 (20) | 98 (40) | 99 (40) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 9.89±5.74 | 8.59±6.46 | 8.06±5.84 |

| Time period of diagnosis | |||

| 1978–1998 | 11 (13) | 33 (39) | 41 (48) |

| 1999–2008 | 35 (19) | 73 (40) | 76 (41) |

| 2009–2018 | 53 (24) | 90 (41) | 74 (34) |

| Diagnostic certainty | |||

| Definite PCD diagnosis | 55 (17) | 137 (43) | 126 (40) |

| Probable PCD diagnosis | 38 (28) | 49 (36) | 50 (36) |

| Clinical diagnosis only | 6 (19) | 10 (32) | 15 (48) |

| Organ laterality | |||

| Situs solitus | 65 (26) | 99 (39) | 90 (35) |

| Situs inversus | 26 (14) | 79 (43) | 77 (42) |

| Heterotaxia | 2 (16) | 5 (42) | 5 (42) |

| Situs status not reported | 6 (16) | 13 (34) | 19 (50) |

| Ultrastructural defect | |||

| Normal | 10 (20) | 19 (40) | 19 (40) |

| Central complex | 10 (25) | 17 (43) | 13 (32) |

| ODA | 21 (19) | 50 (45) | 41 (37) |

| ODA/IDA | 16 (16) | 38 (38) | 47 (46) |

| Microtubular disorganisation | 3 (11) | 14 (50) | 11 (39) |

| Other | 5 (14) | 19 (51) | 13 (35) |

| No information | 34 (28) | 39 (33) | 47 (39) |

| BMI z-scores at first measure | −0.2±1.25 | 0±1.32 | 0±1.23 |

| BMI z-scores at last measure | 0.02±1.2 | 0.13±1.18 | −0.13±1.24 |

| FEV1 z-scores at first measure | −1.96±1.47 | -1.37±1.59 | −0.67±1.52 |

| FEV1 z-scores at last measure | −0.98±1.38 | −1.34±1.57 | −1.96±1.52 |

| FVC z-scores at first measure | −1.43±1.72 | −0.94±1.69 | −0.17±1.53 |

| FVC z-scores at last measure | −0.45±1.49 | −0.58±1.59 | −0.97±1.59 |

| FEV1/FVC z-scores at first measure | −1.14±1.43 | −0.83±1.48 | −0.86±1.41 |

| FEV1/FVC z-scores at last measure | −1.00±1.28 | −1.35±1.26 | −1.75±1.30 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean±sd. Data are presented with row percentages. ODA: outer dynein arm; IDA: inner dynein arm; BMI: body mass index; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity. #: yearly lung function change, improving >0.05 z-scores; stable ≤0.05 and ≥ −0.05 z-scores; decreasing < −0.05 z-scores.

TABLE 3.

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) from the International PCD Cohort compared to Global Lung Function Initiative 2012 reference values (linear mixed effects regression, adjusting for all covariates)

| Estimate (95% CI) | p-value # | |

| Intercept¶ (lung function at age 6 years for “reference patient”) | −1.26 (−2.19– −0.3) | |

| Age at measurement | −0.04 (−0.12–0.04) | |

| Country (ref: Germany) | <0.01 | |

| Australia | −0.34 (−1.26–0.59) | |

| Belgium | −0.20 (−1.03–0.64) | |

| Cyprus | −1.19 (−2.14– −0.23) | |

| Czech Republic | −0.95 (−1.68– −0.22) | |

| Denmark | 0.21 (−0.42–0.84) | |

| France | 0.14 (−0.65–0.93) | |

| Greece | 0.92 (−2.35–4.19) | |

| Israel | 0.11 (−0.71–0.93) | |

| Italy | −0.28 (−1.02–0.47) | |

| The Netherlands | 1.63 (0.84–2.43) | |

| Norway | −0.31 (−1.24–0.63) | |

| Poland | −0.86 (−1.70– −0.03) | |

| Switzerland | 0.13 (−0.63–0.89) | |

| Turkey | −1.76 (−2.46– −1.06) | |

| UK | −1.09 (−1.90– −0.28) | |

| Sex (ref: male) | 0.37 | |

| Female | −0.03 (−0.33–0.27) | |

| Age at diagnosis | −0.01 (−0.05–0.02) | 0.21 |

| Diagnostic period | 0.02 (−0.005–0.05) | 0.26 |

| Diagnostic certainty (ref: definite PCD diagnosis+) | 0.49 | |

| Probable PCD diagnosis§ | −0.04 (−0.43–0.35) | |

| Clinical diagnosis only | 0.38 (−0.27–1.03) | |

| Laterality defects (ref: situs solitus) | 0.59 | |

| Ambiguous | 0.42 (−0.53–1.36) | |

| Situs inversus | 0.33 (−0.001–0.66) | |

| Unknown | 0.15 (−0.54–0.85) | |

| BMI | 0.32 (0.28–0.37) | <0.01 |

| Change of lung function over time ƒ | ||

| Country (ref: Germany) | <0.01 | |

| Australia | −0.02 (−0.10–0.07) | |

| Belgium | 0.02 (−0.05–0.10) | |

| Cyprus | 0.07 (−0.01–0.15) | |

| Czech Republic | 0.04 (−0.03–0.11) | |

| Denmark | −0.01 (−0.07–0.05) | |

| France | −0.05 (−0.12–0.03) | |

| Greece | 0.01 (−0.29–0.32) | |

| Israel | −0.05 (−0.13–0.03) | |

| Italy | −0.03 (−0.10–0.04) | |

| The Netherlands | −0.14 (−0.24– −0.04) | |

| Norway | −0.02 (−0.12–0.09) | |

| Poland | 0.04 (−0.05–0.13) | |

| Switzerland | −0.03 (−0.10–0.05) | |

| Turkey | 0.11 (0.04–0.18) | |

| UK | 0.03 (−0.04–0.11) | |

| Sex (ref: male) | 0.36 | |

| Female | −0.01 (−0.04–0.02) | |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.003 (0.00–0.01) | 0.08 |

| Diagnostic period | −0.001 (−0.004–0.001) | 0.32 |

| Diagnostic certainty (ref: definite PCD diagnosis+) | 0.92 | |

| Probable PCD diagnosis§ | −0.01 (−0.04–0.03) | |

| Clinical diagnosis only | −0.001 (−0.07–0.07) | |

| Laterality defects (ref: situs solitus) | 0.52 | |

| Ambiguous | −0.01 (−0.11–0.08) | |

| Situs inversus | −0.02 (−0.05–0.01) | |

| Unknown | −0.02 (−0.08–0.04) | |

| BMI | 0.02 (0.01–0.02) | <0.01 |

BMI: body mass index. #: likelihood ratio test p-value indicating whether the characteristic explains differences in FEV1 within the study population. ¶: describes the FEV1 of a reference patient at 6 years, who is male, from Germany, with a BMI z-score of 0, diagnosed at birth (age=0) in 1978, with a definite PCD diagnosis. Categorical variables describe the change from the reference category, while continuous variables describe the change from the reference patient for each unit of increase. +: hallmark PCD ultrastructural defect identified by electron microscopy findings or biallelic PCD causing gene mutation based on the European Respiratory Society PCD diagnosis guidelines [19]. §: abnormal light or high-frequency video microscopy finding and/or low (≤77 nL·min−1) nasal nitric oxide value. ƒ: based on interaction terms between the characteristics (e.g. country, sex) and age. Change of lung function over time thus describes the change in the trajectory of FEV1 per year increase, based on the reference category for categorical variables and for each unit of increase for continuous variables.

Determinants of lung function

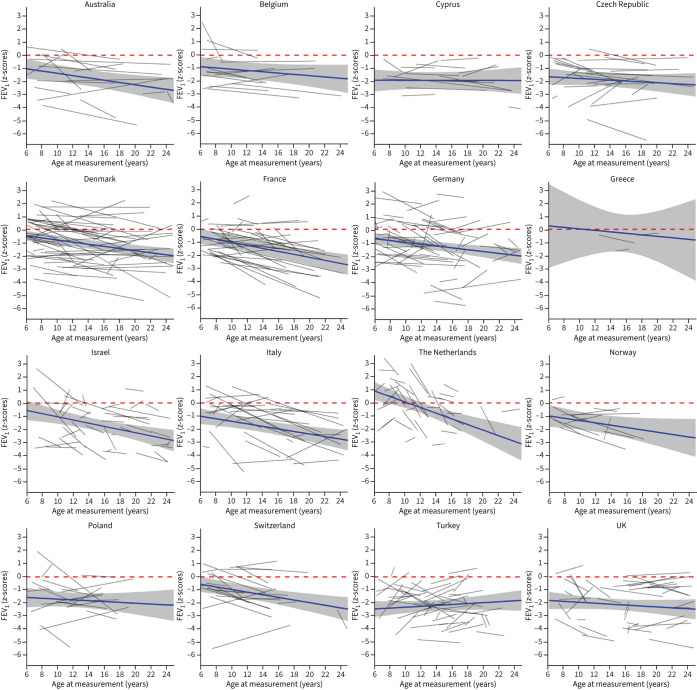

Lung function differed by countries (table 3, supplementary tables S1 and S2, figure 2 and supplementary figure S4). FEV1 was reduced at the age of 6 years in most countries compared to GLI reference values, except the Netherlands. FEV1 z-scores were lowest in Turkey (−3.02), Cyprus (−2.45) and the UK (−2.35), and highest in the Netherlands (0.37) and Denmark (−1.05). The change in FEV1 over time was also variable: lung function deteriorated over time in most countries. Yearly decline of FEV1 z-scores was highest in the Netherlands (−0.14), Israel (−0.05) and France (−0.05). FEV1 z-scores increased over time in Turkey (0.11), Cyprus (0.07) and Poland (0.04). For FVC (supplementary table S1 and supplementary figure S4), the results were similar to FEV1. FVC decreased over time in most countries, except for Turkey (0.08), with the steepest decline in the Netherlands (−0.26). FEV1/FVC was reduced at baseline in all countries and the steepest decline over time was found in German patients (supplementary table S2).

FIGURE 2.

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) trajectories of primary ciliary dyskinesia patients in different countries compared to Global Lung Function Initiative 2012 reference values.

BMI was positively associated with FEV1 and FVC, but not with FEV1/FVC. Patients with higher BMI had a better FEV1 at baseline and improved more over time (table 3 and supplementary table S1). Baseline FEV1 was 0.32 z-scores higher for each unit of higher BMI z-score. Yearly change of FEV1 increased by 0.02 z-scores for each unit of z-score increase in BMI. Similarly, baseline FVC and increase of FVC over time were higher in individuals with higher BMI. BMI remained a determinant for lung function when running separate regression model for countries with ≥30 patients (supplementary table S4).

Ultrastructural defects were also associated with lung function (table 4). Patients with microtubular disorganisation defects had the worst baseline FEV1 z-scores (−1.75), followed by patients with central complex defects (−1.38) and ODA defects (−1.27). Patients with nondiagnostic TEM (−0.91) or combined ODA and IDA defects (−0.60) had the best lung function at baseline. In addition, yearly changes of FEV1 varied between groups, with the steepest decline in patients with ODA and IDA defects (−0.05), and the most favourable course in patients with central complex defects. FVC varied similarly with ultrastructural defects (supplementary table S2), but the evidence was less strong than for FEV1. The amount of variability explained by the model changed only marginally when we additionally included ultrastructural defects into the model: the marginal R2 changed from 0.211 to 0.237 and the conditional R2 from 0.817 to 0.819.

TABLE 4.

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), by ultrastructural defect (n=366)

| Estimate (95% CI) | p-value # | |

| Intercept (lung function at age 6 years for “reference patient”) ¶ | −1.27 (–2.41– –0.13) | |

| Baseline FEV1 | ||

| ODA (ref.)+ | 0.01 | |

| Central complex defect | −0.11 (−0.67–0.45) | |

| ODA/IDA | 0.67 (0.19–1.14) | |

| Microtubular disorganisation | −0.49 (−1.15–0.17) | |

| Nondiagnostic | 0.36 (−0.20–0.91) | |

| Change of FEV1 over time § | −0.02 (−0.12–0.08) | |

| ODA (ref.)+ | 0.04 | |

| Central complex defect | 0.03 (−0.02–0.07) | |

| ODA/IDA | −0.05 (−0.09– −0.01) | |

| Microtubular disorganisation | 0.01 (−0.05–0.08) | |

| Nondiagnostic | −0.01 (−0.06–0.05) |

ODA: outer dynein arm; IDA: inner dynein arm. #: likelihood ratio test p-value indicating whether the characteristic explains differences in FEV1 within the study population. ¶: adjusted for all variables of the full model, the full summary output is in the supplementary material (supplementary table S2). The intercept describes the FEV1 of a reference patient at age 6 years, who is male, from Germany, with a body mass index z-score of 0, diagnosed at birth (age=0) in 1978, with a definite PCD diagnosis. Categorical variables describe the change from the reference category, while continuous variables describe the change from the reference patient for each unit of increase. +: data are presented as unstandardised regression coefficient representing difference from reference category. §: changes in lung function over time are based on interaction terms between the characteristics (e.g. country, sex) and age. The change over time thus describes the change in the trajectory of FEV1 per year increase, based on the reference category for categorical variables and for each unit of increase for continuous variables.

We did not find evidence that FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC z-scores differed by sex, age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, laterality defects, level of diagnostic certainty or isolated pathogen (table 3 and supplementary tables S1 and S5).

FEV1 at baseline was slightly better when we excluded patients diagnosed at the same year as first lung function measurement (FEV1 z-score −1.10, 95% CI −2.11 to −0.09) compared to the total included population (FEV1 z-score −1.26, 95% CI −2.19 to −0.30) (table 3 and supplementary table S6). However, the decline over time did not change.

Discussion

This large international study of patients with PCD found that lung function, already reduced by the age of 6 years, declined further during childhood, adolescence and early adulthood, with an overall negative trend in z-scores. There was heterogeneity between countries and individuals. Overall, FEV1 z-scores decreased over time in 39% of children, remained stable in 40% and improved in 21%. Reduced FEV1/FVC at baseline and follow-up supported presence of obstructive lung disease. Type of ultrastructural defect was marginally associated, and BMI more strongly associated with lung function at baseline and changes in lung function over time.

The wide variation in lung function between countries confirms previous cross-sectional data which included adults [15]. We observed that countries with poor lung function at baseline, such as Poland and Turkey, tended to have a less steep decline than countries with more favourable baseline values such as the Netherlands, Denmark or France. Reasons for this are unclear, but could include regression to the mean and differences in management of PCD. It is possible that patients who presented with a poor lung function at diagnosis were offered strict physiotherapy and antibiotics management and were monitored more closely than patients who were better off at diagnosis. Length of follow-up time and frequency of lung function testing differed between countries, which could have affected the estimation of the lung function trajectories. In the Netherlands and France, where the decline in lung function was steep, the mean lung function trajectory was estimated based on short individual follow-ups, while in countries with longer follow-ups, such as Denmark or Belgium, the decline in lung function was less steep. We modelled mean trajectories as linear, although they may be nonlinear. However, in formal testing including a quadratic term, we found no evidence for nonlinearity. It is also possible that the GLI reference values might not be applicable to all countries, e.g. the Netherlands. However, if that were true, we would expect regional differences in baseline lung function, but the effect on slopes should be minor. Despite the differences between countries, results from the individual country models (supplementary table S3) highlight the robustness of our findings.

Can early diagnosis prevent disease progression? This has been suggested by previous studies [14, 27–29], but the Danish study and ours found no association [8]. As we still lack robust evidence for the best treatments for PCD, management is based on experience from other lung diseases such as cystic fibrosis. Therefore, PCD diagnosis might not have led to a change in management, as patients may have been treated for chronic lung disease already before PCD was diagnosed. PCD-specific randomised controlled trials will provide more specific treatment recommendations [30, 31]. We refer here both to symptomatic treatment such as antibiotics and airway clearance techniques, but also to treatments under development such as gene therapy or transcript therapy [32, 33].

When considering the different phases of lung function over a lifetime [9, 10], what have we learnt? Our study and the North American study suggest that lung function growth during childhood is impaired [13]. The fact that lung function was already low at age 6 years could be the result of poorer lung growth at preschool age or a reduced lung function at birth, or it could be a consequence of neonatal respiratory problems such as atelectasis or neonatal pneumonia. Studies in children with asthma have shown that impaired lung function in infancy is associated with lower lung function in childhood as well as later in life [34, 35], which supports a hypothesis that the reduced lung function in PCD could be associated with neonatal early-life disease. However, this can only be investigated using infant lung function testing in children with PCD diagnosed as neonates. Studies based on mainly adult patients reported larger declines (−0.89% per year in Italy) [8, 24], suggesting that the decline of lung function in adulthood is accelerated. The fact that FEV1 z-scores decreased over time in all studies reflects long-term irreversible lung damage such as bronchiectasis and lung remodelling after recurrent severe infections [36]. On the positive side, the heterogeneity between patients that we followed suggests that many changes are reversible after initiation of regular physiotherapy and antibiotics, such as mucus plugging, bronchial wall thickening and temporary atelectasis.

If we compare lung function decline in patients with PCD to those with cystic fibrosis, we see that lung function decline in PCD patients is comparable to that of cystic fibrosis patients in childhood. However, in young adulthood lung function seems to decline faster in patients with cystic fibrosis [15, 37]. This might indicate a worse disease course in cystic fibrosis than in PCD. Another explanation may be that most younger cystic fibrosis patients have been diagnosed through newborn screening and thus on average have a milder phenotype than older cystic patients who have been diagnosed because they developed symptoms and lung damage has occurred. Patients with PCD in our study have all been diagnosed late, sometimes years or decades after the presentation of symptoms [6, 38]. This could explain the similar lung function for cystic fibrosis and PCD patients early in life despite a more severe disease course in patients with cystic fibrosis. In studies that assessed changes in lung function z-scores over the growth period in children with asthma, there is evidence that some children with asthma have a reduced lung growth compared to children without asthma. In a study from France, Mahut et al. [39] investigated trajectories of FEV1 z-scores in 295 children with asthma followed between the ages of 8 and 15 years. They found that in 4% of the children, FEV1 z-scores improved significantly over time; in 69% of the children FEV1 z-scores remained stable; and in 28% of the children, FEV1 z-scores decreased. McGeachie et al. [40] studied 684 children with mild to moderate asthma aged 5–12 years at baseline and followed them for ≥11 years. They found that 51% had normal lung growth, measured by FEV1 compared to reference values from healthy children, while 49% had reduced lung growth. However, as definitions and methods differed between these studies, a direct comparison with our study is not possible.

Genetic and ultrastructural differences have been offered as an explanation for variable lung function trajectories in smaller studies [8, 13, 41]. Particularly poor lung function was seen in patients with microtubular defects [6, 13, 28, 42]. A UK study in 82 adults reported an FEV1 decline of 0.75% predicted in patients with microtubular defects compared to −0.51% predicted in patients with ODA or combined ODA and IDA defects, and −0.13% predicted in patients with normal or inconclusive TEM. Other studies have shown that annual change in FEV1 % predicted deviated from normal only in patients with central apparatus and microtubular defects (−1.11% predicted) and not in patients with dynein arm defects or normal TEM [13, 24]. We found microtubular defects to be associated with the worst baseline lung function, but further course did not differ. The total variability explained by the regression model (marginal R2) increased only slightly when we included the ultrastructural defects, suggesting that ultrastructural differences explain only a small part of the heterogeneity.

Higher BMI was associated with better baseline lung function and with further change. This confirms previous cross-sectional data in people with PCD [14, 15, 43] and it is in line with what has been found in patients with CF [44]. The effect of poor nutrition on lung function is known for patients with other respiratory diseases [45–47] and dietary support should be provided when required. In contrast to our previous cross-sectional analysis where we found that FEV1 and FVC z-scores were lower in females than males [15], we found no evidence of an association of lung function and sex. This is in line with what was found in the UK [6], and studies in patients with CF [48].

We did not find an association between any of the isolated pathogens in sputum microbiology samples and changes in lung function over time. study in 266 adults with PCD found that participants colonised with P. aeruginosa had lower baseline FEV1 than participants without chronic Pseudomonas; however, there was no difference in lung function decline between colonised and noncolonised participants [49]. In children with cystic fibrosis, in whom sputum pathogens are similar as in patients with PCD, colonisation with P. aeruginosa has been associated with a steeper decline in lung function [50].

With 4470 lung function tests from 486 individuals, this study is by far the largest showing lung function trajectories in children, adolescents and young adults with PCD. Most other longitudinal studies combined children and older adults, not allowing the growth period in childhood to be distinguished from functional decline in adulthood [8, 24]. The large study population made it possible to compare countries and ultrastructural phenotypes and test for association with possible risk factors. A limitation of the study was that the cut-off for defining whether FEV1 z-scores improved, remained stable or decreased was based on cut-offs defined in a study including mostly healthy children, and may therefore not fit a PCD population. However, as yet, no data describing expected normal variability of lung function exist for people with PCD. Another limitation was that some participating centres only provided one measurement per patient per year, and therefore for these patients we may not have captured all variation in lung function over time, although we included only patients with at least three lung function measurements. These centres were instructed to select lung function measurements at random, so this should not have led to selection bias. A further limitation was that we did not have information about whether patients withheld inhaled β-agonists before lung function measurements were performed. In addition, we lacked information about pulmonary exacerbations and could therefore not directly verify whether local centres contributed only lung function tests from patients in a steady state. However, none of the collaborating centres measures lung function in patients during or shortly after an exacerbation, and they had been instructed not to enter any such measurements into the database. Another limitation of the study was that we lacked information on other factors that can influence lung function associated with bronchiectasis from any cause such as frequency of exacerbations, colonising organisms and patterns of care including antibiotic treatments, airway clearance routines and vaccinations. It would also be interesting to study if chest computed tomography scans or magnetic resonance imaging can predict lung function decline in children and adults with PCD, as has been shown in children with cystic fibrosis [51]. Prospective cohort studies using standardised protocols would help to clarify the relative contribution of these factors to the rate of lung function change for patients with PCD [52].

In conclusion, this large international study found considerable heterogeneity in lung function trajectories of children, adolescents and young adults with PCD, and a wide variation between countries. Lung function was low in 6-year-olds and declined further throughout the lung growth period despite treatment. It is essential to develop PCD-specific treatment strategies to improve prognosis.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-01918-2021.Supplement (1.1MB, pdf)

Shareable PDF

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all the patients in the iPCD Cohort and their families, and we are grateful to the PCD support groups that closely collaborate with us. We thank all the researchers in the participating centres who helped collect and enter data and worked closely with us throughout the build-up of the iPCD Cohort.

Footnotes

Author contributions: C.E. Kuehni, F.S. Halbeisen and M. Goutaki developed the concept and designed the study. F.S. Halbeisen cleaned and standardised the data. F.S. Halbeisen and E.S.L. Pedersen performed the statistical analyses. All other authors participated in discussions for the development of the study and contributed data. F.S. Halbeisen, C.E. Kuehni, M. Goutaki and E.S.L. Pedersen drafted the manuscript. All authors commented and revised the manuscript. C.E. Kuehni, F.S. Halbeisen and E.S.L. Pedersen take final responsibility for the contents.

Conflict of interest: P. Latzin reports grants from Vertex and Vifor, payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Vertex, Vifor and OM Pharma, and participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Polyphor, Santhera (DMC), Vertex, OM Pharma and Vifor. M.R. Loebinger reports consultancy fees from Insmed, AstraZeneca and Grifols, and payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Insmed and Grifols. The remaining authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Support statement: This study is supported by Swiss National Science Foundation (320030B_192804). The development of the iPCD Cohort has been funded from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme under EG-GA number 35404 BESTCILIA: Better Experimental Screening and Treatment for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. PCD research at ISPM Bern also receives national funding from the Lung Leagues of Bern, St Gallen, Vaud, Ticino, and Valais, and the Milena-Carvajal Pro Kartagener Foundation. M. Goutaki is supported by a Swiss National Science Foundation fellowship (PZ00P3_185923). Most participating researchers and data contributors participate in the BEAT-PCD clinical research collaboration, supported by the European Respiratory Society and the ERN-LUNG (PCD core). The contribution by the Prague centre was supported by Czech health research council AZV ČR (NV 19-07-00210). Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Kouis P, Goutaki M, Halbeisen FS, et al. Prevalence and course of disease after lung resection in primary ciliary dyskinesia: a cohort & nested case-control study. Respir Res 2019; 20: 212. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1183-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallmeier J, Nielsen KG, Kuehni CE, et al. Motile ciliopathies. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020; 6: 77. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0209-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goutaki M, Halbeisen FS, Barbato A, et al. Late diagnosis of infants with PCD and neonatal respiratory distress. J Clin Med 2020; 9: 2871. doi: 10.3390/jcm9092871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behan L, Dimitrov BD, Kuehni CE, et al. PICADAR: a diagnostic predictive tool for primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 1103–1112. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01551-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noone PG, Leigh MW, Sannuti A, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: diagnostic and phenotypic features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 169: 459–467. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-365OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah A, Shoemark A, MacNeill SJ, et al. A longitudinal study characterising a large adult primary ciliary dyskinesia population. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 441–450. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00209-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halbeisen FS, Jose A, de Jong C, et al. Spirometric indices in primary ciliary dyskinesia: systematic review and meta-analysis. ERJ Open Res 2019; 5: 00231-2018. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00231-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marthin JK, Petersen N, Skovgaard LT, et al. Lung function in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: a cross-sectional and 3-decade longitudinal study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181: 1262–1268. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200811-1731OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speizer FE, Tager IB. Epidemiology of chronic mucus hypersecretion and obstructive airways disease. Epidemiol Rev 1979; 1: 124–142. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bui DS, Lodge CJ, Burgess JA, et al. Childhood predictors of lung function trajectories and future COPD risk: a prospective cohort study from the first to the sixth decade of life. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6: 535–544. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30100-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller MR, Pedersen OF, Lange P, et al. Improved survival prediction from lung function data in a large population sample. Respir Med 2009; 103: 442–448. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marott JL, Ingebrigtsen TS, Çolak Y, et al. Lung function trajectories leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as predictors of exacerbations and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 202: 210–218. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201911-2115OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis SD, Rosenfeld M, Lee HS, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: longitudinal study of lung disease by ultrastructure defect and genotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199: 190–198. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0548OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maglione M, Bush A, Nielsen KG, et al. Multicenter analysis of body mass index, lung function, and sputum microbiology in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Pediatr Pulmonol 2014; 49: 1243–1250. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halbeisen FS, Goutaki M, Spycher BD, et al. Lung function in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: an iPCD Cohort study. Eur Respir J 2018; 52: 1801040. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01040-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ardura-Garcia C, Goutaki M, Carr SB, et al. Registries and collaborative studies for primary ciliary dyskinesia in Europe. ERJ Open Res 2020; 6: 00005-2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00005-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goutaki M, Maurer E, Halbeisen FS, et al. The international primary ciliary dyskinesia cohort (iPCD Cohort): methods and first results. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1601181. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01181-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucas JS, Paff T, Goggin P, et al. Diagnostic methods in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Paediatr Respir Rev 2016; 18: 8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2015.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lucas JS, Barbato A, Collins SA, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1601090. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01090-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strippoli MP, Frischer T, Barbato A, et al. Management of primary ciliary dyskinesia in European children: recommendations and clinical practice. Eur Respir J 2012; 39: 1482–1491. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00073911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halbeisen FS, Shoemark A, Barbato A, et al. Time trends in diagnostic testing for primary ciliary dyskinesia in Europe. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1900528. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00528-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 2012; 40: 1324–1343. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development. Geneva, WHO, 2006. Available from: https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards/standards/weight-for-age [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pifferi M, Bush A, Mariani F, et al. Lung function longitudinal study by phenotype and genotype in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Chest 2020; 158: 117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirkby J, Bountziouka V, Lum S, et al. Natural variability of lung function in young healthy school children. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 411–419. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01795-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakagawa S, Johnson PCD, Schielzeth H. The coefficient of determination R2 and intra-class correlation coefficient from generalized linear mixed-effects models revisited and expanded. J R Soc Interface 2017; 14: 20170213. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2017.0213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yiallouros PK, Kouis P, Middleton N, et al. Clinical features of primary ciliary dyskinesia in Cyprus with emphasis on lobectomized patients. Respir Med 2015; 109: 347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maglione M, Montella S, Mollica C, et al. Lung structure and function similarities between primary ciliary dyskinesia and mild cystic fibrosis: a pilot study. Ital J Pediatr 2017; 43: 34. doi: 10.1186/s13052-017-0351-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker W, Harris A, Rubbo B, et al. Lung function and nutritional status in children with cystic fibrosis and primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: Suppl. 60, PA3128. doi: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2016.PA3128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuehni CE, Goutaki M, Kobbernagel HE. Hypertonic saline in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: on the road to evidence-based treatment for a rare lung disease. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1602514. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02514-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobbernagel HE, Buchvald FF, Haarman EG, et al. Efficacy and safety of azithromycin maintenance therapy in primary ciliary dyskinesia (BESTCILIA): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 493–505. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30058-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paff T, Omran H, Nielsen KG, et al. Current and future treatments in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22: 9834. doi: 10.3390/ijms22189834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuehni CE, Goutaki M, Rubbo B, et al. Management of primary ciliary dyskinesia: current practice and future perspectives. In: Chalmers JD, Polverino E, Aliberti S, eds. Bronchiectasis (ERS Monograph). Sheffield, European Respiratory Society, 2018; pp. 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner SW, Palmer LJ, Rye PJ, et al. Infants with flow limitation at 4 weeks: outcome at 6 and 11 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165: 1294–1298. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200110-018OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez FD, Morgan WJ, Wright AL, et al. Initial airway function is a risk factor for recurrent wheezing respiratory illnesses during the first three years of life. Group Health Medical Associates. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991; 143: 312–316. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.2.312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stocks J, Sonnappa S. Early life influences on the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2013; 7: 161–173. doi: 10.1177/1753465813479428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caley L, Smith L, White H, et al. Average rate of lung function decline in adults with cystic fibrosis in the United Kingdom: data from the UK CF registry. J Cyst Fibros 2021; 20: 86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2020.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuehni CE, Frischer T, Strippoli MP, et al. Factors influencing age at diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia in European children. Eur Respir J 2010; 36: 1248–1258. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00001010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahut B, Bokov P, Beydon N, et al. Longitudinal assessment of loss and gain of lung function in childhood asthma. J Asthma 2022; in press [ 10.1080/02770903.2021.2023176]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGeachie MJ, Yates KP, Zhou X, et al. Patterns of growth and decline in lung function in persistent childhood asthma. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 1842–1852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ellerman A, Bisgaard H. Longitudinal study of lung function in a cohort of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J 1997; 10: 2376–2379. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10102376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis SD, Ferkol TW, Rosenfeld M, et al. Clinical features of childhood primary ciliary dyskinesia by genotype and ultrastructural phenotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 191: 316–324. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1672OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goutaki M, Halbeisen FS, Spycher BD, et al. Growth and nutritional status, and their association with lung function: a study from the international Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Cohort. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1701659. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01659-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Earnest A, Salimi F, Wainwright CE, et al. Lung function over the life course of paediatric and adult patients with cystic fibrosis from a large multi-centre registry. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 17421. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74502-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bott L, Béghin L, Devos P, et al. Nutritional status at 2 years in former infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia influences nutrition and pulmonary outcomes during childhood. Pediatr Res 2006; 60: 340–344. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000232793.90186.ca [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Konstan MW, Butler SM, Wohl ME, et al. Growth and nutritional indexes in early life predict pulmonary function in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 2003; 142: 624–630. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liou TG, Adler FR, Fitzsimmons SC, et al. Predictive 5-year survivorship model of cystic fibrosis. Am J Epidemiol 2001; 153: 345–352. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.4.345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schaedel C, de Monestrol I, Hjelte L, et al. Predictors of deterioration of lung function in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2002; 33: 483–491. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen-Cymberknoh M, Weigert N, Gileles-Hillel A, et al. Clinical impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Respir Med 2017; 131: 241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mésinèle J, Ruffin M, Kemgang A, et al. Risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway infection and lung function decline in children with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2022; 21: 45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2021.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turkovic L, Caudri D, Rosenow T, et al. Structural determinants of long-term functional outcomes in young children with cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1900748. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00748-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goutaki M, Papon JF, Boon M, et al. Standardised clinical data from patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: FOLLOW-PCD. ERJ Open Res 2020; 6: 00237-2019. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00237-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-01918-2021.Supplement (1.1MB, pdf)

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-01918-2021.Shareable (886.1KB, pdf)