Abstract

We conducted one of the first prospective studies to test the hypothesis that the clinical history of priapism underestimates priapism incidence compared with a priapism pain diary. Eligibility criteria were men with sickle cell anemia (SCA) between 18 and 40 years of age who have had at least 3 episodes of priapism in the past 12 months. Seventy-one men with SCA completed the diary for at least 3 months. The first 3 months of the priapism diary were included in the analysis. A total of 298 priapism episodes were recorded, and 80% (57 of 71) of the participants had at least 1 priapism event. Priapism severity was reported in the range of moderate to the worst imaginable pain in 81.5% (263 of 298), and a total 57 participants (80%) had a median pain rating of 6 (interquartile range: 5-8) on a scale from 1 to 10. The monthly incidence rate of priapism per participant based on history versus self-report pain diary was 2.0 (95% confidence interval, 1.9-2.1) and 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.6), respectively (P < .001). For participants that had a prior priapism episode, 80% had another episode during the 3-month interval follow-up. The median time to that second episode was 27.5 days. Major priapism occurred in 9.9% of episodes and was associated with the sum of all prospective priapism events. Men with SCA and at least 3 priapism episodes in the past 12 months are at significant risk for recurrent priapism in the following 3 months.

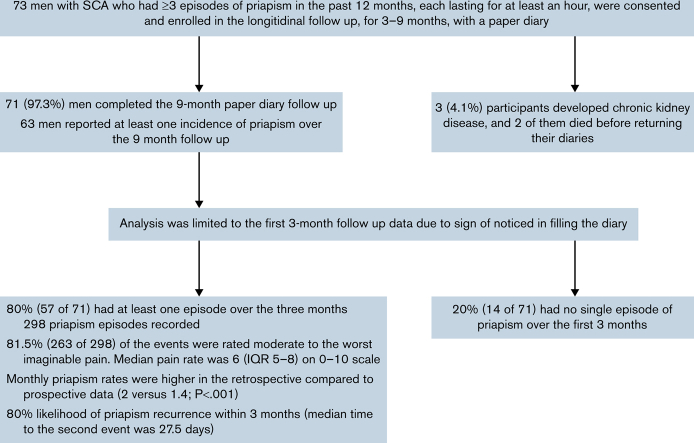

Visual Abstract

Key Points

-

•

Men with SCA and ≥3 priapism events in the prior 12 months have an 80% chance of having a priapism episode within the following 3 months.

-

•

The sum of priapism events in 3 months predicted a major priapism event.

Introduction

Recurrent ischemic priapism (stuttering and major) is a significant but poorly understood sickle cell disease (SCD) related morbidity in boys, adolescents, and men.1 Globally, the burden of SCD is highest in malaria-endemic sub-Saharan Africa, where an estimated 75% of the 300 000 annual SCD births occur.2 In a recently published large survey, the prevalence of priapism among men with sickle cell anemia (SCA, the most severe form of SCD), aged 18 years and above, was 32.6%, of which 74% was stuttering that typically lasted less than 4 hours.3 Apart from painful distress, SCA-related priapism is associated with high mental duress reported in 87% of affected patients who struggled with embarrassment, sadness, shame, anxiety, depression, anger, and exhaustion.3 Perceived severity of priapism is significantly associated with decreased physical wellness, low quality of life, and impaired sexual function.4 Erectile dysfunction is also a known significant priapism-associated morbidity.5,6 The prevalence of erectile dysfunction in young men with SCA is exceptionally high at 44.2%, and there is a related impact on sexual desire, orgasmic function, and satisfaction with sex life.3

Prior priapism studies in SCA primarily relied on individuals’ recall to characterize symptoms and experiences. However, recall bias is a significant concern in estimating the incidence of priapism events leading to either underestimation or overestimation.7 Paper diaries are a reasonable alternative to assess the burden of priapism in SCA or for monitoring treatment and are less likely to be affected by factors influencing recall such as recency, salience, or complexity of an event.7 Additionally, diaries have reduced chances of failure to report symptom variability in recurrent events as each episode is likely to be recorded almost immediately.7 Paper diaries have also been used in prospective studies describing the epidemiology of vaso-occlusive pain events, assessment of hydroxyurea adherence,8,9 and tracking of priapism recurrences in a clinical trial setting.10

An accurate estimate of the incidence of priapism events at home and without a physician contact is required to characterize the full extent of the disease morbidity for patient treatment and assess the impact of therapeutic interventions. Given recall bias, we tested the hypothesis that the patient-reported past priapism clinical history underestimates priapism incidence compared with a priapism paper diary. We also assessed the potential predictors of major priapism (lasting >4 hours) in a cohort of adults with SCA with a history of recurrent priapism.

Methods

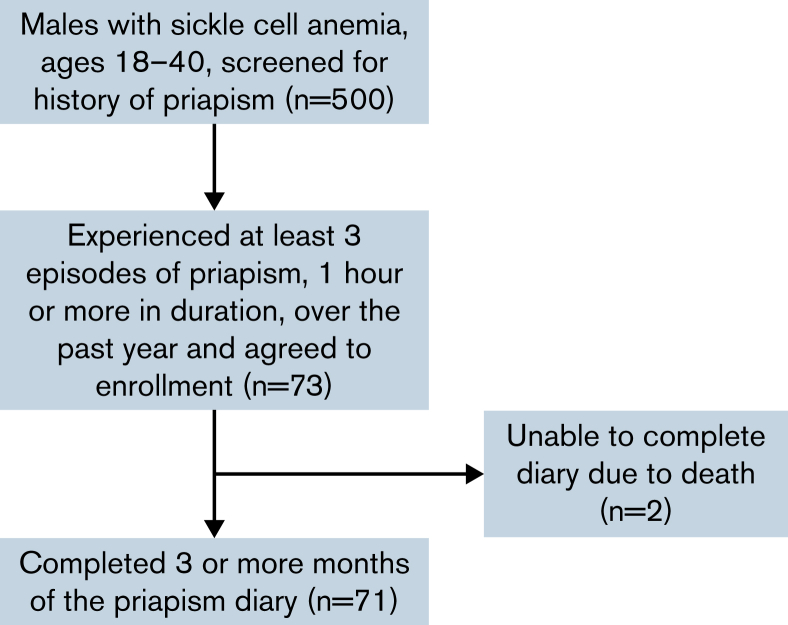

We conducted a prospective cohort study at two sites in Nigeria (Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital and Murtala Mohammed Specialist Hospital). Eligibility criteria were men with SCA between 18 and 40 years of age who have had 3 or more episodes of priapism, each lasting for at least 1 hour, in the past 12 months. The study recruitment and enrollment were commenced in February 2020 and halted in March 2020 because of restrictions imposed from the COVID-19 pandemic. All the participants were identified from the priapism registry established at the 2 hospitals (Figure 1). We initially planned to include 80 participants based on available financial resources, but because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we stopped the study to ensure the safety of participants and the research staff. To our knowledge, this was the first of its kind study; thus, we could not estimate power. The protocol was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram for participant screening, enrollment, and completion of prospective diary.

Baseline demographic and physical findings were recorded. Histories of priapism and comorbid conditions in the past 12 months were also documented. All participants had their early morning blood samples collected and analyzed for sex hormones (testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinizing hormone [LH]), complete blood count, liver function test, electrolytes, and hemoglobin F percentage.

The participants were given a priapism event paper diary to record each episode that occurred prospectively, including the date, the time the event started and the time it resolved, the nature of the pain and severity on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = mild to 10 = excruciating), the relationship of priapism with vaso-occlusive pain and malaria fever, the treatment offered, and the coping mechanisms. To improve the participants’ fidelity to reporting priapism events using the paper diary, we made weekly phone call reminders. However, clinic and study visits were not possible during the time of COVID-19 restrictions. All the participants were followed for at least 3 months (maximum of 9 months) with regular weekly phone calls reminding them about completing the diary. At the end of the follow-up, the diaries were collected and entered into REDCap (an online data management software). However, in the analysis of the final results, we limited the priapism prospective diary data to the first 3 months of follow-up because we noticed signs of decline in completing the diary after the first quarter, including lower question completion rates and declining numbers of episodes (supplemental Appendix).

Definitions

Major priapism is an episode of priapism that lasts ≥4 unabated hours, which may resolve with or without treatment. Minor priapism is an episode of priapism that lasts <4 hours, which may resolve with or without treatment.

We defined gonadal function as follows: eugonadism with testosterone ≥300 ng/dL and LH ≤ 9.4 mUI/mL; primary hypogonadism with testosterone <300 ng/dL and LH > 9.4 mUI/mL; secondary hypogonadism with testosterone <300 ng/dL and LH ≤ 9.4 mUI/mL; and compensated hypogonadism as testosterone ≥300 ng/dL and LH > 9.4 mUI/mL.11

Statistical analysis

Continuous measures were summarized by either the mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile range (IQR), depending on normality, and by count and percentage for categorical measures. A multivariable negative binomial regression model was constructed to predict the future 3-month priapism rate with covariates of age, hemoglobin, testosterone, estimated glomerular filtration rate, hydroxyurea use (yes or no), and retrospective priapism rate as a control. A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed for having at least 1 major priapism episode, with covariates of age, hemoglobin, testosterone, proteinuria, hydroxyurea use (yes or no), and prospective priapism events in 3 months as a control. The covariates were selected based on established or postulated confounder (priapism rate). A 2-sided P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Clinical characteristics of cohort and retrospective reports of priapism

A total of 500 men with SCA were screened for recent frequent priapism episodes.3 From this group, 73 men who had 3 or more priapism episodes in the past year agreed to participate (Figure 1; comparisons of those screened to enrolled are reported in supplemental Table 1). Baseline demographic, physical, and laboratory characteristics of the cohort were reported in Table 1. The median age was 24.0 years (IQR 21.5-28.5), and only 7 (9.6%) were married.

Table 1.

Demographic, physical characteristics, and laboratory results of the cohort of men with sickle cell anemia enrolled in the priapism study (n = 73)

| Characteristic∗ | Summary statistics |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 24.0 (21.5-28.5) |

| Marital status, married | 7 (9.6) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 17.9 (16.6-18.8) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 110.0 (104.5-117.0) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 63.0 (56.0-68.5) |

| On hydroxyurea | 11 (15.1) |

| Total hemoglobin, g/dL | 8.0 (6.9-9.6) |

| Mean cell volume, fl | 84.9 (80.4-92.7) |

| Percent hemoglobin, F% | 4.6 (2.8-8.8) |

| Percent hemoglobin, S% | 85.6 (80.6-88.0) |

| White blood cell count, 109/L | 13.3 (9.6-17.6) |

| Absolute neutrophil count, 109/L | 6.45 (4.55-86.0) |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 297.0 (222.5-363.5) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 540.0 (379.0-729.0) |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 79.0 (46.5-125.5) |

| Direct conjugated bilirubin, mg/dL | 16.0 (11.5-24.0) |

| Indirect unconjugated bilirubin, mg/dL | 79.0 (46.5-125.5) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, IU | 46.0 (34.5-59.0) |

| Alanine aminotransferase, IU | 17.0 (13.0-25.5) |

| Alkaline phosphatase, IU | 98.0 (75.5-128.0) |

| Albumin, g/L | 42.0 (40.0-45.0) |

| Globulin, g/L | 38.0 (34.0-43.0) |

| Testosterone, ng/dL | 8.1 (6.4-10.1) |

| Follicles stimulating hormone, mlU/mL | 5.6 (4.0-7.3) |

| Luteinizing hormone, mlU/mL | 7.2 (5.5-9.9) |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 59.0 (52.5-85.0) |

| Urea | 2.8 (2.3-5.2) |

| Proteinuria, positive | 26 (35.6) |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 155.0 (128.0-166.7) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 3 (4.1) |

| Leg ulcer, n (%) | 3 (4.1) |

| Avascular necrosis | 11 (15.1) |

| Malaria, n (%) | 55 (75) |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | 25 (34.2) |

Median (inter-quartile range) for continuous variables and counts (percentages) for categorical variables. BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (derived using CKD-EPI Creatinine Equation 2021).

Characteristics of their retrospective priapism history are reported in Table 2. A total 68 participants (95.8%) rated their baseline historical priapism pain to be at least moderate to the worst imaginable pain (median 7, IQR 5-8). Typical descriptions of the baseline priapism pain were piercing (47.9%), throbbing (38.4%), and burning (34.2%). The pain commonly involved both the penile shaft and glans penis (58.4%), but rarely affected the whole perineal area (9.6%). Only 5 participants (6.8%) reported priapism pain radiating to other body sites, and the abdomen was the most common (40%). A total of 11 participants (15.1%) had priapism coexisting with vaso-occlusive pain, which occurred simultaneously in 27.2%. The severity of priapism pain was at least similar or worse than vaso-occlusive pain in 43.8%.

Table 2.

Retrospective priapism characteristics of a cohort of men with sickle cell anemia enrolled in the priapism study (n = 73)

| Characteristic | Summary statistics |

|---|---|

| Age at first priapism event, mean (SD) | 18.7 (4.3) |

| Priapism events in the past 12 mo, median (IQR) | 8.0 (4.0-25.0) |

| Duration of priapism event (min), median (IQR) | 120.0 (45.0-180.0) |

| Priapism triggers,∗n (%) | |

| Sleep | 38 (52.1) |

| Sexual urge | 18 (24.7) |

| Dehydration | 4 (5.5) |

| Fever | 4 (5.5) |

| Drugs | 1 (1.4) |

| Other | 6 (8.2) |

| Don't know | 19 (26.0) |

| Location of priapism pain, n (%) | |

| All over the penis | 40 (54.8) |

| Penis shaft | 20 (27.4) |

| Whole perineum | 7 (9.6) |

| Glans penis | 6 (8.2) |

| Nature of priapism pain,∗n (%) | |

| Piercing | 35 (47.9) |

| Throbbing | 28 (38.4) |

| Burning | 25 (34.2) |

| Cramping | 10 (13.7) |

| Crushing | 9 (12.3) |

| Stabbing | 4 (5.5) |

| Other | 3 (4.1) |

| Priapism pain on a scale from 1 (mild) to 10 (excruciating/ worst possible), median (IQR) | 7.0 (5.0-8.0) |

| Priapism pain radiates to other parts of the body, n (%) | 5 (6.8) |

| When pain radiates, to what other parts of the body, n (%); n = 5 | |

| Abdomen | 2 (40.0) |

| Hip | 1 (20.0) |

| Thigh | 1 (20.0) |

| Other | 1 (20.0) |

| Coping mechanisms that relieve priapism events at home,∗n (%) | |

| Exercise | 44 (60.3) |

| Cold shower | 25 (34.2) |

| Hot shower | 11 (15.1) |

| Ice pack | 3 (4.1) |

| Analgesics | 3 (4.1) |

| Other | 3 (4.1) |

| None | 11 (15.1) |

| Sought medical treatment for priapism in the past 12 mo, n (%) | 25 (34.2) |

| Which medical treatment(s) worked,∗n (%); n = 25 | |

| Stilbesterol | 6 (24.0) |

| Analgesics | 6 (24.0) |

| Hydroxyurea | 3 (12.0) |

| None | 12 (48.0) |

| Penile aspiration in the past 12 mo, n (%) | 2 (2.7) |

| Surgical shunt in the past 12 mo, n (%) | 1 (1.4) |

| Medications currently on for priapism, n (%); n = 71 | |

| Stilbesterol | 5 (7.1) |

| Hydroxyurea | 3 (4.3) |

| Analgesics | 2 (2.9) |

| None | 61 (87.1) |

| Any priapism associated with vaso-occlusive pain, n (%); n = 72 | 11 (15.3) |

| If associated, when did the vaso-occlusive pain occur, n (%); n = 11 | |

| Just before priapism | 4 (36.4) |

| Along with priapism | 3 (27.3) |

| Immediately after priapism | 4 (36.4) |

| How does priapism pain compare with typical pain crisis, n (%) | |

| Better | 41 (56.2) |

| Similar | 15 (20.5) |

| Worse | 17 (23.3) |

SD, standard deviation.

More than 1 response allowed.

Only 25 (34.2%) sought medical treatment for their recurrent priapism at the time of enrolment. Among the medical treatments offered to them in the past 12 months, stilbesterol (24%), analgesia (24%), and hydroxyurea (12%) subjectively appeared to have worked for them; however, in the remaining 48%, none of the treatments worked. There was also a very low rate of surgical interventions in the cohort, with a penile aspiration rate of 2.7% (2 of 73) and a surgical shunt rate of 1.4% (1 of 73) in the past 12 months.

Prospective reports of priapism and other characteristics

During the follow-up period, 4.1% (3 of 73) of the participants were diagnosed with chronic kidney disease, of which 2 died before the study follow-up was completed. A total of 71 participants completed the diary for at least 3 months. Of the 71 who completed the diary, 63 reported at least 1 incident of priapism prospectively over the follow-up duration of 9 months, with counts ranging from 1 to 34. The rate of priapism events showed a steeper dropoff over the first 2 to 3 months, which we attribute to response fatigue (Figure 2). Only the first 3 months of the diary were used to ensure more valid estimates of priapism episodes, resulting in 298 incidents included in the prospective analyses. Based on missing priapism duration in 5 events out of 298, the analysis of major priapism was limited to 293 events. Table 3 reports the future diary results.

Figure 2.

Histogram of months to priapism events for all diary months. There is a substantial decline in events over time, so only the first 3 months of data are used for prospective analyses.

Table 3.

Characteristics of priapism in a prospective cohort of 71 men with sickle cell anemia who completed a priapism diary for three months, with a total of 298 priapism episodes

| Characteristic | Summary statistics |

|---|---|

| Rate per year of priapism events, mean (95% CI) | 16.8 (14.9-18.8) |

| Duration of priapism event (min), median (IQR); n = 293 | 90.0 (40.5-135.0) |

| Type of priapism incident, n (%); n = 293 | |

| Minor | 264 (90.1) |

| Major | 29 (9.9) |

| Had at least 1 major priapism event, n (%) | 18 (25.4) |

| Priapism triggers,∗ n (%) | |

| Sleep | 234 (78.5) |

| Sexual urge | 37 (12.4) |

| Dehydration | 11 (3.7) |

| Fever | 10 (3.4) |

| Sexual intercourse | 1 (0.3) |

| Don't know | 5 (1.7) |

| Priapism pain on a scale from 1 (mild) to 10 (excruciating/worst possible), median (IQR) | 6.0 (5.0-8.0) |

| Location of priapism pain, n (%); n = 295 | |

| All over the penis | 96 (32.5) |

| Penis shaft | 126 (42.7) |

| Whole perineum | 40 (13.6) |

| Glans penis | 33 (11.2) |

| Nature of priapism pain, n (%) | |

| Piercing | 58 (19.5) |

| Throbbing | 7 (2.3) |

| Burning | 96 (32.2) |

| Crushing | 28 (9.4) |

| Stabbing | 20 (6.7) |

| Cannot explain | 89 (29.9) |

| Did any coping mechanisms relieve priapism event at home, n (%); n = 296 | 253 (85.5) |

| Coping mechanisms that relieved priapism event at home,∗n (%); n = 250 | |

| Exercise | 146 (65.6) |

| Cold shower | 22 (8.8) |

| Hot shower | 9 (3.6) |

| Ice pack | 15 (6.0) |

| Analgesics | 15 (6.0) |

| Other | 25 (10.0) |

| Vaso-occlusive pain associated with priapism event, n (%); n = 297 | 30 (10.1) |

| If associated, when did the vaso-occlusive pain occur, n (%); n = 30 | |

| Just before priapism | 12 (40.0) |

| Along with priapism | 7 (23.3) |

| Immediately after priapism | 11 (36.7) |

| Compared with your usual sickle cell pain, how bad was this priapism pain. n (%); n = 29 | |

| Milder | 5 (17.2) |

| Same severity | 7 (24.1) |

| Worse | 11 (37.9) |

| Cannot say | 6 (20.7) |

More than 1 response allowed.

The median number of diary-reported priapism events per participant was 2, and the median duration of priapism episodes was 1.5 hours. Fifty-seven (80.3%) of the participants documented at least 1 episode, and 80.7% (46 of 57) who had 1 episode had a second within the 3-month diary period. At least 1 major priapism episode was reported by 18 (25.4%) participants within 3 months. Prospectively, the severity of priapism pain was reported to be at least moderate to the worst imaginable pain in 81.5% (263 of 298), with a median pain report of 6 (IQR 5-8) on a scale from 1 to 10. The most common descriptions of the pains were burning (32.2%), piercing (19.5%), and crushing (9.4%); whereas 29.9% could not describe the pain. In only 2.3% of the episodes (7 of 298) was emergency treatment sought for the priapism event. The majority identified sleep (78.5%) and sexual urge (12.4%) as the triggers of the priapism, whereas few identified dehydration (3.7%) or fever (3.4%) as priapism triggers.

Comparison of retrospective to prospective priapism diary rates

The annual priapism event rate was significantly higher from the retrospective record than in the prospective diary (23.6 vs 16.8 events per patient-year, respectively; P < .001), contrary to our hypothesis (Table 4). The Spearman correlation between the 2 rates was 0.57 (P < .001). The rate of priapism was also significantly higher among those with at least 1 major priapism episode (2.1 events/mo vs 1.2 events/mo, respectively; P < .001). There was no significant difference in the rate of prospective priapism among those with eugonadism, hypogonadism, or compensated hypogonadism (P = .340).

Table 4.

Risk factors associated with the prospective rate of priapism in men with sickle cell anemia

| Characteristic | Priapism rate (95% CI) | P value∗ |

|---|---|---|

| Retrospective and prospective priapism rates, events per year (n = 73) | <.001 | |

| Retrospective from history (n = 73) | 23.6 (22.5-24.8) | |

| Prospective from diary (n = 71) | 16.8 (14.9-18.8) | |

| Monthly priapism rate by experiencing major priapism in prospective period | <.001 | |

| No major priapism (n = 53) | 1.2 (1.0-1.3) | |

| At least one major priapism (n = 18) | 2.1 (1.8-2.5) | |

| Monthly priapism rate by gonadal hormone status | .340† | |

| Eugonadism (n = 48) | 1.5 (1.3-1.7) | |

| Hypogonadism (n = 5) | 0.7 (0.3-1.2) | |

| Compensated hypogonadism (n = 18) | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) | |

| Monthly priapism rate by use of hydroxyurea | <.001 | |

| No hydroxyurea (n = 60) | 1.2 (1.0-1.3) | |

| Hydroxyurea (n = 11) | 2.7 (2.2-3.3) | |

| Monthly rate of priapism in months 2 and 3 by whether priapism occurred in first month | .006 | |

| No priapism in first month (n = 26) | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | |

| Priapism in first month (n = 45) | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | |

Fisher exact test unless otherwise noted.

Negative binomial regression.

Factors associated with prospective priapism

We constructed a multivariable negative binomial regression model for the 3-month rate of prospective priapism, with age, use of hydroxyurea, hemoglobin, testosterone, proteinuria, and retrospective monthly priapism rate. Data for 1 participant was an outlier (the participant had the highest prospective rate but a much lower retrospective rate), which greatly influenced model estimation based on standard influence statistics. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) indicated that the model without the outlier was better fitting (AIC 338.4 compared to 349.6), so we estimated the model with 70 participants. Retrospective priapism rate was the only covariate associated with prospective priapism, with an incidence rate ratio of 1.18 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08-1.28; P < .001), Table 5. No other covariates were associated with prospective priapism.

Table 5.

Multivariable negative binomial regression model for priapism rate in a three-month prospective period among participants with a recurrent history of priapism in the past 12 mo (n = 70)

| Variable | Incidence rate ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment | 1.03 | 0.97-1.09 | .335 |

| Testosterone, ng/dL | 1.04 | 0.92-1.18 | .568 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 0.89 | 0.74-1.08 | .239 |

| Hydroxyurea | 1.08 | 0.50-2.33 | .854 |

| eGFR | 0.86 | 0.44-1.68 | .660 |

| Retrospective monthly priapism rate | 1.18 | 1.08-1.28 | <.001 |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Factors associated with major priapism

We constructed a multivariable logistic regression model for major priapism, with age, use of hydroxyurea, hemoglobin, testosterone, proteinuria, and the prospective number of priapism events. As with the model for future priapism rate, we estimated the model with 70 participants because the data for 1 participant was an outlier, which had a significant influence on the model. The AIC indicated that the model without the outlier was better fitting (AIC 82.5 compared to 85.2). In the logistic regression model, only the sum of priapism events in 3 months was associated with major priapism. Each additional event increased the odds of developing major priapism by 1.16 (95% CI, 1.01-1.32; P = .03; supplemental Table 2). No other covariates were associated with major priapism.

Discussion

Recurrent ischemic priapism is a common and debilitating complication of males with SCA. Unfortunately, few priapism-related SCA clinical trials with small sample sizes, nonconclusive evidence for optimal therapy, and limited estimates of the priapism incidence rates have been completed.12 The absence of an estimated incidence rate for priapism limits clinical trial design for secondary prevention of priapism. To our knowledge, we report the first prospective assessment of the priapism incidence rate based on an observational priapism diary. Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find evidence that recall bias associated with patient history underestimates priapism incidence compared with a prospective priapism pain diary. However, in a preselected group of men with a history of priapism in the last month, annualized, the 3-month history of priapism indicates a significant disease burden.

As far as we know, for the first time, we have identified a subgroup of men that have a near-term risk of priapism and have estimates of their incidence rate of priapism (number of new events per month). Based on a history of the prior 12 months, men with at least 3 preceding priapism events should be counseled on their increased risk of priapism for at least the next 3 months. For such high-risk individuals, we would suggest an in-depth history regarding therapy associated with priapism (vaso-reactive agents, antidepressants, anxiolytics, α-blockers, antihypertensives, antipsychotics, anticoagulants, sex hormones, drugs for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and recreational drugs) and a discussion of the pros and cons of stopping the medications (supplemental Table 3). We would also encourage an explanation of potential increased near-term risk for priapism, including risk for major priapism that may require urology intervention.13,14

Currently, the US Food and Drug Administration has no approved therapies for secondary prevention of priapism in SCD. Typically, before initiating a new agent in children, the safety and efficacy are first demonstrated in adults. Thus, we wanted to focus on the clinical history of priapism in men with SCD that had multiple priapism episodes because this is the age group most likely to enroll in a randomized clinical trial that uses new agents to prevent priapism recurrence. An important finding in this research is that a group of men with a high rate of future priapism events has been identified for the first time. This approach is relevant because investigators can plan randomized controlled trials with an estimate of the anticipated incidence rate for priapism in adults with SCA. Several randomized controlled trials have used the strategy to identify the subgroup of potential participants most likely to have future pain events. Specifically, in the double-blind, randomized controlled clinical trial determining the efficacy of hydroxyurea compared with placebo, the participants were selected if they had a history of 3 or more such pain crises per year. Similarly, in the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial of crizanlizumab, the participants were selected if they had 2 to 10 sickle cell-related pain episodes in the 12 months before enrollment.15 For future secondary prevention of priapism trials, we have identified a group that could be preselected for participation based on the results of this prospective cohort study.

No randomized controlled trial has provided definitive evidence for the secondary prevention of priapism in SCA. However, for a high-risk group of men likely to have priapism, potential therapies including hydroxyurea,16 phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors,17 or regular blood transfusion18 should be considered for a fixed period to evaluate the therapy’s benefit to attenuate the incidence rate of priapism. For any high-risk patient presenting with priapism for several hours, we would consider prompt urology consult to prevent major priapism and not to wait for the recommended 4 hours for urology intervention with a penile aspiration to achieve detumescence. With a huge burden of approximately about 17 priapism events per person-year reported in this population, there is a compelling need for an evidence-based solution to address the distressing morbidity.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is also the first to comprehensively define the intensity of the priapism pain episodes and the risk factors for significant priapism. Adding to this novelty, we demonstrate that increased monthly minor priapism events are associated with the subsequent development of a major priapism episode. The significance of this finding is that a targeted reduction in monthly events will likely prevent major priapism, which is a risk factor for erectile dysfunction.19 We did not demonstrate that priapism recurrences were associated with hypogonadism. Similarly, Morrison reported that hypogonadism and baseline testosterone levels were not associated with priapism events.20 About 7% and 25.4% of the cohort with priapism have secondary hypogonadism and compensated hypogonadism, respectively. The high prevalence of compensated hypogonadism is similar to what was reported in another study in Brazil.11 An unanticipated finding was the high prevalence of chronic kidney disease and short-term mortality occurring in men with a history of priapism. Without a comparison group followed prospectively, we could not determine an association between recurrent priapism and renal disease. Such an association is worthy of future evaluation, as vasculopathy is a significant driver of many incapacitating SCA complications.21, 22, 23

Our study has unavoidable limitations. First, because of COVID-19 restrictions, participants may have been distracted, leading to them not completing the diary. We also could not have outpatient clinic and study visits during the lockdown period, which we partly addressed using regular weekly phone calls. We noticed signs of fatigue in completing the diary, which was evident after the third month. We addressed this limitation by restricting our analysis to the first 3-month follow-up data instead of the planned 9 months and weekly phone calls to check the number of priapism episodes. In an Italian registry of individuals with SCD, hospitalizations for acute vaso-occlusive pain events decreased significantly during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic when compared with the immediate period before the pandemic.24 However, our prospective study focused on recording the priapism events at home and not at the hospital. Thus, the pandemic likely had minimum impact on the home diary record during the first 3 months of the study. Priapism is often a manifestation of the hemolytic subphenotype of SCD that is associated with increased mortality, pulmonary hypertension, leg ulcers, and strokes linked to increased hemolysis; however, we could not determine whether there was an increased prevalence of the previously mentioned phenotypes when compared with individuals without priapism.21

In conclusion, we have comprehensively characterized a prospective SCA cohort’s priapism-related pain, pattern, and predictors. We have further demonstrated that in the prior 12 months, men with at least 3 self-reported priapism episodes are at substantial risk for priapism episodes in the following 3 months. Most significantly, as a selection criterion for future priapism, we have established that the number of minor priapism events is associated with future risk of at least 1 major priapism event. The high-risk group of men with 3 priapism events in the prior 12 months should be counseled about their near-term risk of additional priapism events and considered for secondary priapism prevention treatment and early surgical intervention when presenting to the emergency department with unresolved priapism.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.R.D. and his institution are the sponsors of 2 externally funded research investigator-initiated projects. Global Blood Therapeutics (GBT) provides funding for the cost of the clinical studies but is not a co-sponsor of either study. M.R.D. is not receiving any compensation for the conduct of these 2-investigator-initiated observational studies. Also, M.R.D. is a member of the Global Blood Therapeutics advisory board for a proposed randomized controlled trial for which he receives compensation, the chair of the steering committee for NOVARTIS-supported phase 2 (SPARTAN) trial to prevent priapism in men, and a medical advisor for the development of the CTX001 Early Economic Model. M.R.D. provided medical input on the economic model as part of an expert reference group for Vertex/CRISPR CTX001 Early Economic Model and provided general information to Forma Pharmaceuticals in 2021 and 2022. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the generous support of Afolabi Family Philanthropic funds and Philips Family donation. I.M.I. was supported by the American Society of Hematology (ASH) Global Research Award.

Authorship

Contribution: I.M.I., A.L.B., and M.R.D. designed the study; I.M.I., A.A., J.A.G., S.A.A., and A.U.J. performed the study; M.R. and M.R.D. performed the analysis; I.M.I. wrote the first draft; I.M.I., S.A.A., M.R., A.K., A.L.B., and M.R.D. revised the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the final draft.

Footnotes

Contact the corresponding author for data sharing: m.debaun@vumc.org.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Arduini GAO, Trovó de Marqui AB. Prevalence and characteristics of priapism in sickle cell disease. Hemoglobin. 2018;42(2):73–77. doi: 10.1080/03630269.2018.1452760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piel FB, Hay SI, Gupta S, Weatherall DJ, Williams TN. Global burden of sickle cell anaemia in children under five, 2010-2050: modelling based on demographics, excess mortality, and interventions. PLoS Med. 2013;10(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Idris IM, Abba A, Galadanci JA, et al. Men with sickle cell disease experience greater sexual dysfunction when compared with men without sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2020;4(14):3277–3283. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Idris IM, Bonnet K, Schlundt D, et al. Psychometric impact of priapism on lives of adolescents and adults with sickle cell anemia: a sequential independent mixed-methods design. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2022;44(1):19–27. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000002056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett N, Mulhall J. Sickle cell disease status and outcomes of African-American men presenting with priapism. J Sex Med. 2008;5(5):1244–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anele UA, Burnett AL. Erectile dysfunction after sickle cell disease-associated recurrent ischemic priapism: profile and risk factors. J Sex Med. 2015;12(3):713–719. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stull DE, Leidy NK, Parasuraman B, Chassany O. Optimal recall periods for patient-reported outcomes: challenges and potential solutions. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(4):929–942. doi: 10.1185/03007990902774765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dampier C, Ely B, Brodecki D, et al. Pain characteristics and age-related pain trajectories in infants and young children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(2):291–296. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith WR, Ballas SK, McCarthy WF, et al. Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia The association between hydroxyurea treatment and pain intensity, analgesic use, and utilization in ambulatory sickle cell anemia patients. Pain Med. 2011;12(5):697–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olujohungbe AB, Adeyoju A, Yardumian A, et al. A prospective diary study of stuttering priapism in adolescents and young men with sickle cell anemia: report of an international randomized control trial – The priapism in sickle cell study. J Androl. 2011;32(4):375–382. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.110.010934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribeiro AP, Silva CS, Zambrano JC, et al. Compensated hypogonadism in men with sickle cell disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2021;94(6):968–972. doi: 10.1111/cen.14428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinegwundoh FI, Smith S, Anie KA. Treatments for priapism in boys and men with sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004198.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olujohungbe A, Burnett AL. How I manage priapism due to sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2013;160(6):754–765. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ. Priapism: current principles and practice. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34(4):631–642. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ataga KI, Kutlar A, Kanter J, et al. Crizanlizumab for the prevention of pain crises in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(5):429–439. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saad ST, Lajolo C, Gilli S, et al. Follow-up of sickle cell disease patients with priapism treated by hydroxyurea. Am J Hematol. 2004;77(1):45–49. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou LT, Burnett AL. Regimented phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor use reduces emergency department visits for recurrent ischemic priapism. J Urol. 2021;205(2):545–553. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anele UA, Le BV, Resar LMS, et al. How I treat priapism. Blood. 2015;125(23):3551–3558. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-551887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spycher MA, Hauri D. The ultrastructure of the erectile tissue in priapism. J Urol. 1986;135(1):142–147. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45549-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison BF, Anele UA, Reid ME, et al. Is testosterone deficiency a possible risk factor for priapism associated with sickle-cell disease? Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47(1):47–52. doi: 10.1007/s11255-014-0864-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato GJ, Hebbel RP, Steinberg MH, et al. Vasculopathy in sickle cell disease: biology, pathophysiology, genetics, translational medicine, and new research directions. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(9):618–625. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato GJ. Priapism in sickle-cell disease: a hematologist’s perspective. J Sex Med. 2012;9(1):70–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kato GJ, Steinberg MH, Gladwin MT. Intravascular hemolysis and the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(3):750–760. doi: 10.1172/JCI89741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munaretto V, Voi V, Palazzi G, et al. AIEOP Red Cell Disorder Working Group Acute events in children with sickle cell disease in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic: useful lessons learned. Br J Haematol. 2021;194(5):851–854. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.