Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this review was to estimate the effect of COVID-19-related restrictions (i.e., stay at home orders, lockdown orders) on reported incidents of domestic violence.

Methods

A systematic review of articles was conducted in various databases and a meta-analysis was also performed. The search was carried out based on conventional scientific standards that are outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) and studies needed to meet certain criteria.

Results

Analyses were conducted with a random effects restricted maximum likelihood model. Eighteen empirical studies (and 37 estimates) that met the general inclusion criteria were used. Results showed that most study estimates were indicative of an increase in domestic violence post-lockdowns. The overall mean effect size was 0.66 (CI: 0.08–1.24). The effects were stronger when only US studies were considered.

Conclusion

Incidents of domestic violence increased in response to stay-at-home/lockdown orders, a finding that is based on several studies from different cities, states, and several countries around the world.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, COVID-19, Domestic violence, Lockdowns

1. Overview

In April 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic was wreaking havoc on the lives and economies of nations worldwide, governments around the world began to institute stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders to help stop the spread of the virus. The result of these orders, while well-intentioned, also tended to increase stress and anxiety as a result of being confined to one's place of residence away from friends, family, schools, and the workplace—the latter of which was severely impacted by shuttered businesses and high unemployment.

Although from one public health vantage point, these orders made a lot of sense, there was also concern that they could be associated with other adverse outcomes, including in particular child abuse and domestic violence, in large part because parents and children were now confined to their homes without access to those who may be able to see the signs of abuse and violence and/or obtain the assistance necessary to escape violent situations. Combined, the stay-at-home orders as well as the economic impact of the pandemic heightened the factors that tend to be associated with domestic violence: increased male unemployment, the stress of childcare and homeschooling, increased financial insecurity, and maladaptive coping strategies. All of these, and more, increase the risk of abuse or escalate the level of violence for women who have previous experience of violence by their male counterparts as well as violence by previously non-violent partners.

So much of a concern about these types of victimization led twenty-one leaders of prominent worldwide organizations, including the World Health Organization, UN Women, and UNICEF, to release a joint statement calling for action to protect children from violence (Joint Leaders' statement - Violence against children: A hidden crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic (who.int)) as well as UN Secretary Guterres' ominous warning: “We know lockdowns and quarantines are essential to suppressing COVID-19, but they can trap women with abusive partners... Over the past weeks, as the economic and social pressures and fear have grown, we have seen a horrifying surge in domestic violence” (U.N. Chief Urges Governments: ‘Prioritise Women's Safety’ As Domestic Abuse Surges During Coronavirus Lockdowns (forbes.com); Global Lockdowns Resulting In ‘Horrifying Surge’ In Domestic Violence, U.N. Warns: Coronavirus Updates: NPR). Soon thereafter, media reports emerged calling attention to the links between COVID-19, lockdown orders, and increases in domestic violence worldwide (How Domestic Abuse Has Risen Worldwide Since Coronavirus - The New York Times (nytimes.com)).1

Since the first quarter of 2020, researchers have moved with rapid speed to get a sense of the impact on a wide array of outcomes that could be associated with the coronavirus and related policies designed to stop the spread of the virus, including criminal activity Eisner and Nivette (2020) and Rosenfeld et al. (2021), drug use and abuse (Engel et al., 2020), educational (OECD, 2020) and employment (Fana et al., 2020) outcomes, and so forth. In this article, we contribute to this growing body of research by moving beyond narrative reviews (e.g., Peterman & O'Donnell, 2020) and conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of COVID-19-related restrictions (i.e., stay-at-home orders, lockdown orders) on reported incidents of domestic violence.

2. Systematic search strategy

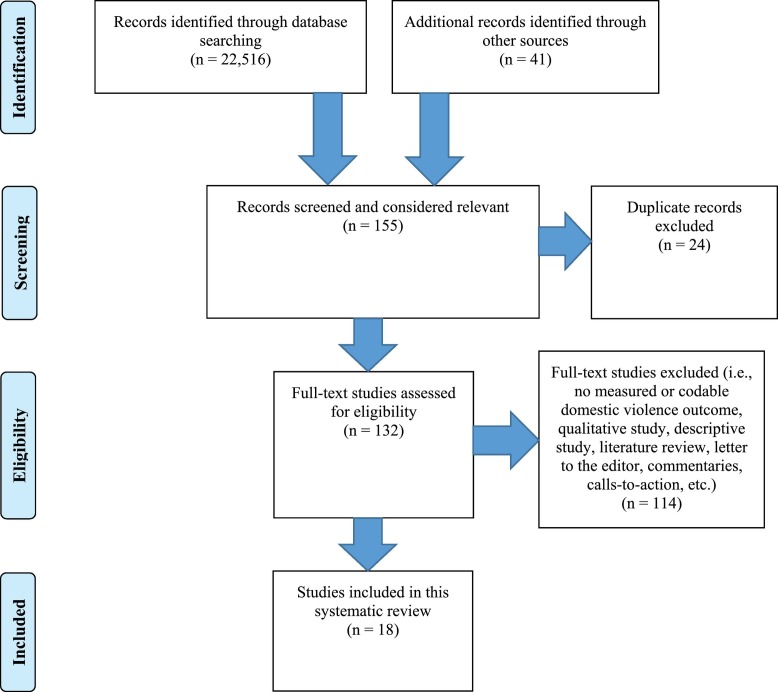

This systematic search of the extant literature was carried out based on conventional scientific standards that are outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P; Moher et al., 2015; Shamseer et al., 2015) and with those that are consistent with guidelines and best practices established in previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Piquero et al., 2016a; Piquero, Farrington, Welsh, Tremblay, & Jennings, 2009; Piquero, Jennings, Diamond, & Reingle, 2015; Piquero, Jennings, & Farrington, 2010; Piquero, Jennings, Farrington, Diamond, & Reingle Gonzalez, 2016b). First, keyword searches using terms such as “domestic violence”, or “intimate partner violence”, or “violence against women”, and “COVID-19” or “SARS-CoV-2” or “2019-nCoV”, or “coronavirus” were performed across the following seven databases: (1) SocINDEX; (2) Scopus; (3) PubMed; (4) JSTOR; (5) ScienceDirect; (6) Google Scholar; and (7) Dissertation Abstracts. Second, hand searches were carried out on leading journals in criminology to identify additional sources. Third, the reference lists of the identified and eligible studies were consulted. Fourth, experts in this area of research identified through their lead authorship on publications on this topic and/or media or social media mentions of their research on this topic were consulted for their knowledge of any relevant studies, particularly those that were not yet published. Finally, existing and authoritative reviews of the literature on the topic were also consulted (Mittal & Singh, 2020; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020; Sánchez, Vale, Rodrigues, & Surita, 2020). The PRISMA flow chart (Moher et al., 2015; Shamseer et al., 2015) that illustrates the funnel by which we filtered and identified the relevant studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis is displayed in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram Outlining the Funneling and Identification of Relevant Studies.

The criteria utilized in order to determine the eligibility of studies for this systematic review are outlined here. First, the study must have had a measurable and codable domestic violence outcome that was assessed prior to and post the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and COVID-19-related restrictions (i.e., stay-at-home orders, lockdowns, etc.). Second, the domestic violence data must have been derived from administrative/official pre-post records (i.e., not retrospective self-reports; see e.g., Hamadani et al. (2020) and Morgan and Boxall (2020)).2 Third, although there was no geographic restriction to the location of the study, the study must have been published in English. Fourth, both published and unpublished studies were considered. Finally, qualitative studies, descriptive studies, and studies that were not empirical (i.e., literature reviews, letters to the editor, commentaries, calls-to-action, etc.) were not included because they do not provide necessary information for our analyses.

3. Results

The systematic literature search that was performed in accordance with the steps outlined above was carried out between December 15, 2020 and January 27, 2021. Beginning with over 22,000 records identified at the outset of the search, the penultimate (for study analyses) search yielded 18 empirical studies that met the general inclusion criteria, and details for these studies including the study #, author/s, publication year, study site, time frame of the study, and the domestic violence outcome measurement is displayed in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Description of studies included in this review (n = 18)

| Study # | Author/s | Publication Year | Site of Study | Time Frame of Study | Domestic Violence Measurement | Main Analytic Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ashby | 2020 | 16 large cities in the USA | January 13, 2020 – May 4, 2020 | Official police-recorded domestic violence crimes (DV; serious assaults in residences) | Seasonal Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Averages (SARIMA) |

| 2 | Bullinger et al. | In progress, 2021 | Chicago, IL, USA | January 1, 2019 to April 14, 2020 | Domestic violence police calls for service and domestic violence crimes (DV; domestic violence, disturbance, and battery) | Difference-in-Differences (DID) |

| 3 | Campedelli et al. | In press, 2021 | Los Angeles, CA, USA | January 1, 2017 to March 28, 2020 | Official domestic violence crime reports (IPV; intimate partner assault) | Bayesian Structural Time-Series (BSTS) |

| 4 | de la Miyar et al. | In press, 2021 | 16 Districts of Mexico City, Mexico | January to May of 2019 and January to May of 2020 | Administrative data from Mexico City's Attorney General's Office for domestic violence crimes (DV) | Event Study Specification and Differences-in-Differences (DID) |

| 5 | Di Franco et al. | 2020 | Sicily, Italy | January 1 to June 2, 2020 | Emergency room admissions for domestic violence (DV) | t-tests |

| 6 | Evans et al. | In press, 2021 | Atlanta, GA, USA | Weeks 1–31 of 2018, 2019, and 2020 | Official domestic violence police crime data (DV) | Descriptive analysis and layered bar chart with percent changes |

| 7 | Gerell et al. | In press, 2021 | Sweden | 2019 and Weeks 3–21 of 2020 | Administrative Swedish police data for domestic violence crimes (DV; indoor assaults) | Poisson regression analysis |

| 8 | Gosangi et al. | 2021 | Northeastern USA | March 11 to May 3, 2017–2019 and 2020 | Administrative health records for domestic violence (IPV) | t-tests, χ2 tests, Poisson regression analysis |

| 9 | Hsu & Henke | In press, 2021 | 35 cities, 1 county in 22 states in the USA | January 1 to May 24, 2020 | Official domestic violence police incidents, calls for service, and crimes (IPV-related; exclude threats, child abuse, child neglect, domestic sexual assaults, protective order violations, and nonviolent family disturbances) |

Fixed-effects regression analysis |

| 10 | Leslie & Wilson | In progress, 2021 | 14 large metropolitan cities in USA | March to May 2020 | Official domestic violence calls for service (DV; excluding child abuse) | Event Study Specification and Differences-in-Differences (DID) |

| 11 | McLay et al. | In progress, 2021 | Chicago, IL, USA | March 2019 and March 2020 | Official domestic violence police reports (DV; exclusively reports that involved physical or sexual violence) | Logistic Regression analysis |

| 12 | Mohler et al. | 2020 | Los Angeles, CA, USA; Indianapolis, IN, USA | Los Angeles, CA: January 2 to April 18, 2020 Indianapolis, IN: January 2 to April 21, 2020 |

Official domestic violence police calls for service (DV) | Interrupted Time Series analysis |

| 13 | Nix & Richards | In press, 2021 | 6 large cities in the USA | January 1, 2018 to December 27, 2020 | Official domestic violence police calls for service (DV) | Interrupted Time Series analysis |

| 14 | Payne & Morgan | In progress, 2021 | Queensland, Australia | February 2014 to March 2020 | Official domestic violence offense rates from the Queensland Government Open Data Portal (DV; breaches of domestic violence orders) | Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Averages (ARIMA) |

| 15 | Perez-Vincent et al. | In progress, 2020 | Buenos Aires, Argentina | January 1 to April 30, 2017–2020 | Administrative government records of calls to a domestic violence hotline (DV) | Difference-in-Differences (DID) |

| 16 | Piquero et al. | 2020 | Dallas, Texas, USA | January 1 to April 27, 2020 | Official police domestic violence incident reports (DV) | Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Averages (ARIMA) |

| 17 | Ravindran & Shah | In progress, 2021 | 577 out of 640 Districts in India | January 2018 to May 2020 | Administrative records of domestic violence complaints received by the National Commission for Women (DV) | Difference-in-Differences (DID) |

| 18 | Rhodes et al. | 2020 | Trauma Center in South Carolina, USA | March 16 to April 30, 2019 and 2020 | Administrative health records on domestic violence (DV) | χ2 tests |

Note. DV = Domestic Violence; IPV = Intimate Partner Violence.

Given the short time frame that has occurred since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic (January 30, 2020, according to the World Health Organization) and the search of eligible studies (December 15, 2020 - January 27, 2021), all of the studies were either published in 2020 or 2021, in press/forthcoming in 2021, or in progress in 2020/2021 (non-peer-reviewed, unpublished manuscripts). Specifically, 5 studies were published in 2020 (Ashby, 2020; Di Franco, Martines, Carpinteri, Trovato, & Catalano, 2020; Mohler et al., 2020; Piquero et al., 2020; Rhodes, Petersen, Lunsford, & Biswas, 2021), 1 study was published in 2021 (Gosangi et al., 2021), 6 studies were in press/forthcoming in 2021 (Campedelli, Aziani, & Favarin, 2021; de la Miyar, Balmori, Hoehn-Velasco, & Silverio-Murillo, 2021; Evans, Hawk, & Ripkey, 2021; Gerell, Kardell, & Kindgren, 2021; Hsu & Henke, 2020; Nix & Richards, 2021), and 6 studies were in progress in 2021 (Bullinger, Carr, & Packham, 2020; Leslie & Wilson, 2020; McLay, 2021; Payne & Morgan, 2020; Perez-Vincent, Carreras, Gibbons, Murphy, & Rossi, 2020; Ravindran & Shah, 2020). There was a wide geographic representation among the studies, with 12 studies being based in the United States and representing many cities and counties (Ashby, 2020; Bullinger et al., 2020; Campedelli et al., 2021; Evans et al., 2021; Gosangi et al., 2021; Hsu & Henke, 2020; Leslie & Wilson, 2020; McLay, 2021; Mohler et al., 2020; Nix & Richards, 2021; Piquero et al., 2020; Rhodes et al., 2021) and other study sites representing countries around the world including Mexico (de la Miyar et al., 2021), Italy (Campedelli et al., 2021), Sweden (Gerell et al., 2021), Australia (Payne & Morgan, 2020), Argentina (Perez-Vincent et al., 2020), and India (Ravindran & Shah, 2020).

The 18 studies frequently focused on a short time frame (i.e., weeks or months) for the pre- and post-COVID-related restrictions domestic violence outcome data, although many studies included pre-COVID-related restrictions data from the prior year or years (i.e., pre-2020) (Bullinger et al., 2020; Campedelli et al., 2021; de la Miyar et al., 2021; Evans et al., 2021; Gerell et al., 2021; Gosangi et al., 2021; McLay, 2021; Nix & Richards, 2021; Payne & Morgan, 2020; Perez-Vincent et al., 2020; Ravindran & Shah, 2020; Rhodes et al., 2021). In addition, the domestic violence pre-post COVID-19-related restrictions data was derived from administrative/official records from police crime/incident reports, police calls for service, domestic violence hotline registries, or health records.

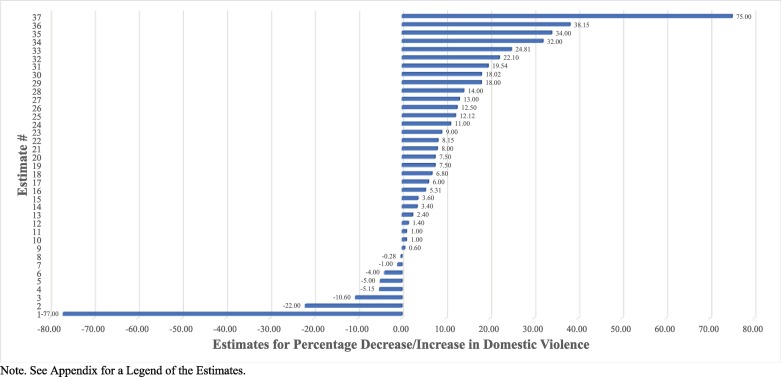

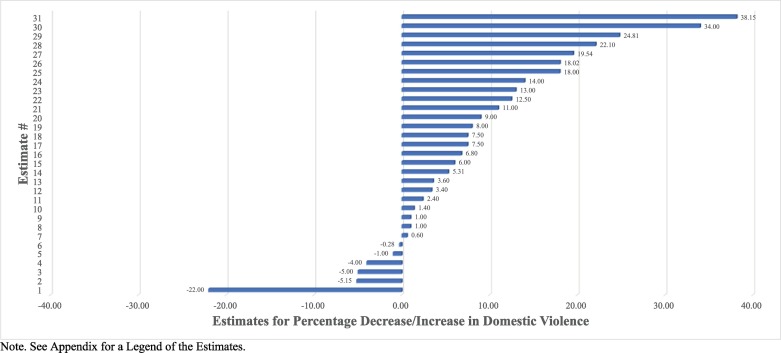

Fig. 2a graphically illustrates the range of the study-specific estimates of the percentage decrease/increase in domestic violence that occurred following the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and post-COVID-19-related restrictions relative to domestic violence that was documented prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and post-COVID-19-related restrictions. According to the 37 %-change estimates available from the 18 included studies,3 eight of the study estimates reported a decrease in domestic violence (range = −0.28% to −77.0%) compared to the 29 study estimates that reported an increase in domestic violence during the post-COVID-19 pandemic's emergence and post-COVID-19-related restrictions (range = +0.60% to +75.0%). If we were to calculate an overall pre−/post- percentage difference, our results would indicate that the average of the 37 positive and negative %-changes amounts to a 7.86% increase in domestic violence. Fig. 2b reports these same results but for only the US-based studies and the result %-change in domestic violence indicates that the average of 31 positive and negative %-changes equates to an 8.10% increase in domestic violence.

Fig. 2.

a. Pre-Post Percentage Decrease/Increase in Domestic Violence (n = 18 studies; 37 estimates). b. US ONLY: Pre-Post Percentage Decrease/Increase in Domestic Violence (n = 12 studies; 31 estimates).

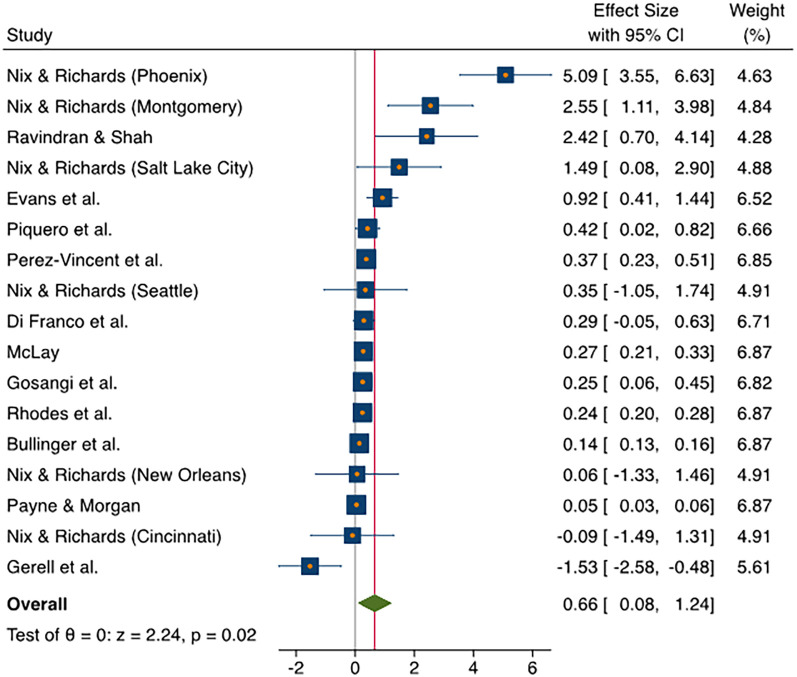

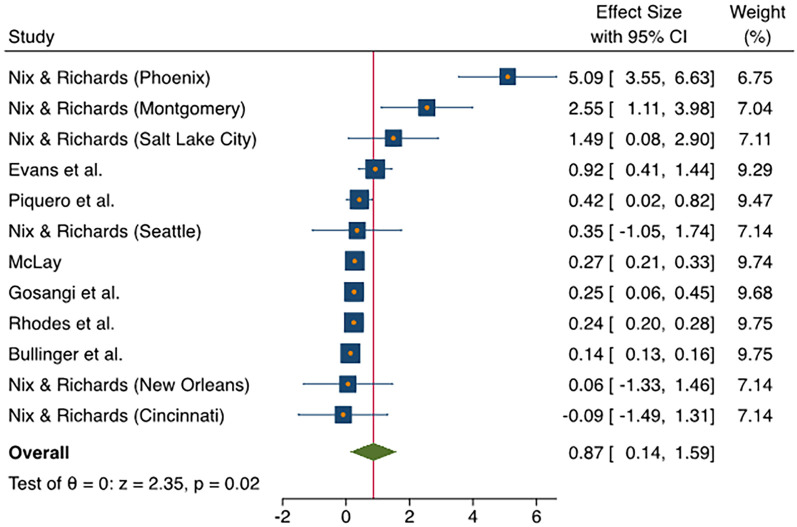

In the final stage of the analysis, effect sizes were generated for those included studies that reported sufficient information for an effect size to be calculated, which is not always the case when collating studies to include for meta-analyses. Fig. 3a provides a forest plot illustrating the distribution of the effect sizes with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals and related weights for the 12 studies (17 effect sizes). As can be seen, the majority of the effect sizes are positive (15 out of 17) and significant (12 out of 17) indicating that “the treatment” (i.e., the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and COVID-19-related restrictions) increased domestic violence. The overall mean effect size generated from a random effects restricted maximum likelihood model was 0.66 (95% CI: 0.08–1.24; z = 2.24, p < .05), representing a medium effect.4 Fig. 3b provides the same forest plot but only for the US-based studies. Among only the US-based studies (7 studies, 12 effect sizes), the mean effect size increases to 0.87 (95% CI: 0.14–1.59). Finally, publication bias/small study effects were formally evaluated with the Begg test (Begg & Mazumdar, 1994),5 and the result from this test did not detect any significant publication bias/small study effects (Begg: z = −0.37, p = .77).

Fig. 3.

a. Forest Plot of the Distribution of the Effect Sizes (n = 12 studies; 17 effect sizes). b. US ONLY: Forest Plot of the Distribution of the Effect Sizes (n = 7 studies; 12 effect sizes).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine whether policies implemented to reduce the spread of the coronavirus, namely stay-at-home or lockdown orders, were associated with any changes in domestic violence using administrative/official pre-post records. Our work was focused on systematically reviewing the literature on any potential changes in domestic violence after restrictions were put into place.

Following systematic review protocol, our initial research started with over 22,000 records identified through database searches as being potentially eligible for inclusion. After our eligibility criteria were imposed, we ended with 18 studies that were included in the systematic review, which is substantively similar to many such reviews in the criminological literature. These 18 studies yielded a total of 37 estimates, the results of which showed an overwhelming increase (pre-post) in reports of domestic violence. Specifically, 29 of the 37 study estimates showed a significant increase. Finally, our forest plot of the distribution of effect size estimates, based on the information necessary to perform such calculations (12 studies and 17 effect sizes), showed an overall medium effect size of 0.66. In short, the evidence is strong that incidents of domestic violence increased in response to stay-at-home/lockdown orders, a finding that is based on several studies from different cities, states, and several countries around the world.

To be sure, while our results rely on the available research that met our inclusion criteria that exists at this time, it remains a sampling of the work that is being done and not yet known. As well, much of the early work that has focused on crime changes in response to the pandemic-related lockdown orders relies on short windows of observations, a few weeks or months. But this is true of the publication process, whereby the time an article has gone through review and published many months have passed since the researchers finalized their data collection. Therefore, continued follow-ups are needed to add to and update our database going forward. Another limitation of our work is that the database relies mainly from U.S. studies, in large part because those are the studies that fit the criteria outlined in our search parameters. We know, for example, that domestic violence is a serious problem in the Americas, and in particular in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMIC) where there is a significant amount of violence, but little is noted in administrative data nor is there much help to aid victims. As a consequence, we anticipate that when researchers carry out sustained analyses of domestic violence in LMIC countries, they will likely uncover a devasting toll on women and children. Lastly, our work relies on official records, which suffer from a variety of problems. At the same time, other sources of domestic violence data, such as self-reports, have tended to show some short-term increases in domestic violence as well (Jetelina, Knell, & Molsberry, 2021). Additional work is needed to assess whether there are enough studies in that line of work to perform a similar analysis to the one carried out in this study. The same is true from the data reports from service providers (Pfitzner, Fitz-Gibbon, Meyer, & True, 2020). The more we can triangulate the data on domestic violence as a result of lockdown orders to gain a more complete picture of changes in victimization experiences, the better and more confident our penultimate conclusions can be.

5. Conclusion and policy implications

The results of this study underscore the importance of increasing the knowledge base about domestic violence, as there have been concerns raised by public health leaders, victim/survivor advocates, women's and children's groups, activists, and policymakers around the world about the potential significant spike in abuse related to the pandemic (see e.g., the Lancet Commission on Gender-Based Violence and Maltreatment of Young People, Knaul, Bustreo, & Horton, 2020). The global economic impact of COVID-19, record levels of unemployment, added stressors in the home—including the care and home schooling of children, financial instability, and illness or death caused or exacerbated by the virus—combined with the mental health toll of social distancing measures required by the epidemiological response, have undermined the decades of progress made in reducing the extent and incidence of domestic violence. In turn, the results of this systematic review call for significant attention to the policy responses and resources that are needed to attend to victims and survivors of domestic abuse that may not be getting the services they need. In particular, Galea, Merchant, and Lurie (2020) note the need to direct resources to historically marginalized groups and those likely to be disproportionately isolated during the pandemic, including older adults, women, and children with past experiences with violence and abuse, and those with ongoing mental illness and chronic health conditions—and it is certainly possible that these effects are magnified for women and children of color, immigrants or refugees, and/or households that speak a language other than English. In addition, the gendered impacts of the pandemic will be far-reaching and in need of sustained research and policy attention (Wenhma, Smith, & Morgan, 2020), especially those programs and policies that are the intersection between women and children such as income transfer programs.

It is also important for our response to domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic to learn from the lessons of responding to previous health crises, natural disasters, and major disruptions that may offer direction and guidance (Sánchez et al., 2020). There is strong evidence to suggest that women's physical and mental health, including the risk of first-time or escalating domestic violence, is connected to the consequences of natural disasters and epidemics, including social isolation, economic instability, and increasing relationship and family conflict (Campbell & Jones, 2016; Parkinson, 2019).

The governor of Puerto Rico recently declared a state of emergency related to gender-based violence, noting it to be a serious social and public health problem that has gotten worse as a function of the territory's economic turmoil, Hurricane Maria, and now the COVID-19 pandemic (Florido, 2021). Similar to Puerto Rico, there needs to be equally strong global, federal, and state level leadership to make these bold and decisive declarations, but also commitments to expand victims' access to health and support services and economic resources directed to families during and after the pandemic. We must look to collaborative and creative thinking, as well as to skilled and experienced victim advocates who have been providing and building upon increasingly evidence-based services for over four decades, on how to expand the availability and diversity of these services and resources, particularly transitional housing options for victims who may have contracted or been exposed to COVID-19. For those victims who report to law enforcement, there will be a need for more intensive police, social services, and victim advocacy follow-up both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Research will also need to explore whether the pandemic's impact on the incidence of domestic violence is sustained in the long-term.

While this systematic review provides strong evidence of increased officially reported domestic violence as a consequence of the COVID-19 stay-at-home and lockdown orders, the exact nature and context of the increase remains unknown. Increased reporting to the police, emergency rooms, and other healthcare settings may be a function of an increased number of victimizations, but also an increase in the decisions by some victims to call the police and seek criminal justice interventions. That is, changes in official reporting rates reflect both a change in extent of victimization experiences, but also the help-seeking decisions of those who were victims of domestic violence prior to and during the pandemic. The increase may include reports by a new set of domestic violence victims whose violence experiences are largely a function of the current economic impact of the pandemic, as well as the temporary isolation resulting from social distancing measures and stay-at-home orders (e.g., the abuse they experienced pre-pandemic was largely emotional in nature and circumstances surrounding the pandemic escalated that emotional control to acts of physical violence). The pandemic may have also served as the catalyst for those who were victims prior to the pandemic to report their experiences due to the increased incidence and severity of violence by their previously abusive partners.

While the findings in this study note increases in officially reported domestic violence, the direction of future research needs to include careful joint analyses of estimates from police agencies, shelter-based and clinical data, and self-report victimization data before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic to estimate the diverse types and context of domestic violence and also examine the ways in which the pandemic have placed women at further risk for physical violence, emotional and financial abuse, and coercive control in the long-term. Chandan et al. (2020) note that the selection bias associated with police, healthcare, and other administrative datasets consistently underestimate the extent and impact of domestic violence, a well-established finding in research before the pandemic. They conclude that without ongoing data collection and surveillance, it will not be possible to estimate the total burden of domestic violence both during and after the pandemic.

The stay-at-home measures have placed those most vulnerable to violence and abuse in close proximity to their potential abuser, and this may lead to a continued increase in the risk factors associated with domestic violence. The cause of this increase is likely to be shaped by a variety of factors that are associated with domestic violence more generally, but that have and will continue to be more prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic. This includes social isolation and increased attempts by abusers to exert power and coercive control, unemployment, economic distress, marital conflict, and substance use and abuse. The financial stress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic has been unprecedented and is likely to disproportionately impact victims and survivors of domestic violence in the long-term. Women's economic dependence on male partners will continue to place many women at risk for new and continued domestic violence. Moreover, the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on unemployment among women, which is estimated to be four times greater for women as compared to men (Sasser Modestino, 2020; Tappe, 2020), along with their increasing responsibility for childcare and home-schooling, will exacerbate the financial challenges of women trying to navigate leaving violent relationships. Patrick et al. (2020) have identified a number of other financial stressors related to the pandemic, including increased food insecurity, decreased employer-sponsored insurance coverage for their children, and the loss of regular childcare leading to women's increasing unemployment, which in turn will lead to devastating impacts for domestic violence victims. Kashen, Glynn, and Novello (2020) point to the need for immediate and long-term action in the area of work-family policies and childcare infrastructure in order to mitigate these impacts.

Increases in domestic violence during the pandemic will also take a tremendous toll on the children living in violent homes and those directly exposed to domestic violence and abuse. As Phelps and Sperry (2020) note, for many children, schools are their only option for mental health services and trauma-informed care and support—not to mention adequate nutrition. It will therefore be important to direct research to examine the impact of the increase in domestic violence during the pandemic on children, given the well-established research on the diverse impacts of family violence on children, and the literature pointing to the intergenerational transmission of violence (Spatz-Widom, 1989). Research has already demonstrated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among parents and children with respect to social isolation, loneliness, and depression. Research by Patrick et al. (2020) finds that in the year since the beginning of the pandemic, a quarter of parents reported worsening mental health for themselves and a 14% worsening in the behavioral health of their children. They find that the combined impact of lack of child-care due to school closures, reduced access to healthcare due to closures and delays in visits, and declines in food security led to the most substantial declines in a family's mental and behavioral health. It is clear that these negative economic circumstances and declining mental health among parents and children, combined with the trauma of violence exposure, are likely to have substantial detrimental impacts for children long-term.

Researchers and policy makers will need to identify both the short- and long-term implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on the risk for domestic violence and subsequent consequences. This includes an understanding of the nature of domestic violence and types of victimizations that come to the attention of the police, and how police agencies may better address this changing crime problem, as well as those that do not get reported to law enforcement and how to address those situations. For those victims reporting their victimization experiences to the police, but choosing—or being forced—to remain with their abuser, there will be a need for more intensive law enforcement, social services, and victim advocacy follow-up both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Federal governments will need to ensure that financial stimulus packages aimed at reducing the economic impact of the pandemic on families also include targeted resources for women and children leaving violent homes, and at the same time earmark resources for victim service and healthcare providers seeing an increase in their caseloads related to domestic violence during and after the pandemic. Boserup, McKenney, and Elkbuli (2020) note the importance of making screening tools and assessments for domestic violence more readily available in diverse community, clinical, and healthcare settings, particularly via telehealth. This may also include collaboration between COVID-19 testing and vaccination sites and police agencies and domestic violence response organizations to include abuse screenings and safety planning. Finally, there will need to be creative approaches to reaching out to those women and children most at risk and often least likely to come to the attention of official agencies and victim response organizations. This includes the expansion of telehealth and remote victim services, expansion of team-based behavioral response units, and the development of innovative referral systems for any and all agencies and providers responding to calls for help from victims and survivors experiencing abuse in their home.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the reviewers for helpful comments as well as the Council of Criminal Justice for their support of this project, the early results of which are available here: NCCCJ - Impact Report: COVID-19 and Domestic Violence Trends (counciloncj.org).

Footnotes

To be sure, there are reasons to believe that reported incidents of domestic violence could have both decreased and increased with COVID-19-related policies. With respect to the former, it is possible that potential victims may feel scared about calling for help because their aggressor is in the household and could instill further harm. With respect to the latter, individuals are now being huddled up in their homes which could exacerbate the stress and anxiety that was already being caused by the coronavirus and lockdown orders, which may lead to escalating anger and potential violence. Our belief is that the latter is likely to be a more accurate representation of the picture, especially since there is corroborative evidence that calls to domestic violence shelters and providers also have coincided with reports of increases in domestic violence (Wood, Schrag, Baumler, et al., 2020).

And to remind readers, these data do not permit us to isolate the proportion of cases where the victim was male or female, but we anticipate that the majority of domestic violence records used in the studies we consider are female-victim.

The study estimates out-number the number of included studies as some of the studies provided a range (low/high) of estimates (for example, Bullinger et al., 2020) and some studies reported estimates separately for different locations/jurisdictions (for example, Ashby, 2020; Nix & Richards, 2021).

A second overall weighted mean effect size was estimated from a random effects restricted maximum likelihood model after removing the two outlier effect sizes (Nix & Richards: Phoenix, 2021 and Gerell et al., 2021) as a sensitivity analysis. The results were similar (positive and significant) with the overall mean effect size being 0.28 (95% CI: 0.17–0.39; z = 5.04, p < .05). As such, we opted to retain these two studies in the overall mean effect size as presented in the text and main analysis.

The Begg test is an adjusted rank correlation test proposed by Begg and Mazumdar (1994) as a statistical tool to examine and identify potential publication bias/small study effects in meta-analysis. Similar to all methods of assessing publication bias, it is important to perform these kind of evaluative tests because of the well known “file drawer problem” that exists wherein larger sample size studies and/or studies with statistically significant effects are more likely to be published, i.e., non-significant effects or small studies are “placed in a file drawer” and not published because they face a difficulty getting published.

Indicates that the study was included in this systematic review.

Appendix A. Appendix

Legend for Fig. 2a estimates

1. de la Miyar et al. (Study #4);

2. Ashby (Study #1; Baltimore, MD);

3. Gerell et al. (Study #7);

4. McLay (Study #11);

5. Ashby (Study #1; Nashville, TN);

6. Campedelli et al. (Study #3; 1st posttest);

7. Nix & Richards (Study 13; Cincinnati,

OH; 1st post-test);

8. Campedelli et al. (Study #3; 2nd posttest);

9. Rhodes et al. (Study #18);

10. Nix & Richards (Study #13; New

Orleans, LA; 1st post-test);

11. Nix & Richards (Study #13; New

Orleans, LA; 2nd post-test);

12. Nix & Richards (Study #13;

Cincinnati, OH; 2nd post-test);

13. Nix & Richards (Study #13;

Montgomery County, MD; 2nd post-test);

14. Nix & Richards (Study #13; Seattle,

WA; 1st post-test);

15. Nix & Richards (Study #13; Seattle,

WA; 2nd post-test);

16. Hsu & Henke (Study #9);

17. Ashby (Study #1; Phoenix, AR);

18. Bullinger et al. (Study #2; DV 911

calls; low estimate);

19. Bullinger et al. (Study #2; DV 911

calls; high estimate);

20. Leslie & Wilson (Study # 10);

21. Ashby (Study #1; Los Angeles,

California);

22. Payne & Morgan (Study # 14);

23. Ashby (Study #1; Austin, TX);

24. Evans et al. (Study #6);

25. Di Franco et al. (Study #5);

26. Piquero et al. (Study # 16);

27. Ashby (Study #1; Dallas, TX);

28. Gosangi et al. (Study #8);

29. Ashby (Study #1; Louisville, KY);

30. Nix & Richards (Study #13; Phoenix,

AZ; 2nd post-test);

31. Nix & Richards (Study #13; Salt Lake

City, UT; 1st post-test);

32. Nix & Richards (Study #13;

Montgomery County, MD; 1st post-test);

33. Nix & Richards (Study #13; Salt Lake

City, UT; 2nd post-test);

34. Perez-Vincent et al. (Study #15);

35. Ashby (Study #1; Montgomery

County, MD);

36. Nix & Richards (Study #13; Phoenix,

AZ; 1st post-test);

37. Ravindran & Shah (Study # 17).

Legend for Fig. 2b Estimates

1. Ashby (Study #1; Baltimore, MD).

2. McLay (Study #11);

3. Ashby (Study #1; Nashville, TN);

4. Campedelli et al. (Study #3; 1st posttest);

5. Nix & Richards (Study 13; Cincinnati,

OH; 1st post-test);

6. Campedelli et al. (Study #3; 2nd posttest);

7. Rhodes et al. (Study #18);

8. Nix & Richards (Study #13; New.

Orleans, LA; 1st post-test);

9. Nix & Richards (Study #13; New

Orleans, LA; 2nd post-test);

10. Nix & Richards (Study #13;

Cincinnati, OH; 2nd post-test);

11. Nix & Richards (Study #13;

Montgomery County, MD; 2nd post-test);

12. Nix & Richards (Study #13; Seattle,

WA; 1st post-test);

13. Nix & Richards (Study #13; Seattle,

WA; 2nd post-test);

14. Hsu & Henke (Study #9);

15. Ashby (Study #1; Phoenix, AR);

16. Bullinger et al. (Study #2; DV 911

calls; low estimate);

17. Bullinger et al. (Study #2; DV 911

calls; high estimate);

18. Leslie & Wilson (Study # 10);

19. Ashby (Study #1; Los Angeles,

California);

20. Ashby (Study #1; Austin, TX);

21. Evans et al. (Study #6);

22. Piquero et al. (Study # 16);

23. Ashby (Study #1; Dallas, TX);

24. Gosangi et al. (Study #8);

25. Ashby (Study #1; Louisville, KY);

26. Nix & Richards (Study #13; Phoenix,

AZ; 2nd post-test);

27. Nix & Richards (Study #13; Salt Lake

City, UT; 1st post-test);

28. Nix & Richards (Study #13;

Montgomery County, MD; 1st post-test);

29. Nix & Richards (Study #13; Salt Lake

City, UT; 2nd post-test);

30. Ashby (Study #1; Montgomery

County, MD);

31. Nix & Richards (Study #13; Phoenix,

AZ; 1st post-test).

References⁎

- *Ashby M.P.J. Initial evidence on the relationship between the coronavirus pandemic and crime in the United States. Crime Science. 2020;9:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40163-020-00117-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg C.B., Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boserup B., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bullinger L.R., Carr J.B., Packham A. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. COVID-19 and crime: Effects of stay-at-home orders on domestic violence. No. w27667. Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L.M., Jones S.J. An innovative response to family violence after the Canterbury earthquake events: Canterbury family violence collaboration’s achievements, successes, and challenges. Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies. 2016;20:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- *Campedelli G.M., Aziani A., Favarin S. Exploring the immediate effects of COVID-19 containment policies on crime: an empirical analysis of the short-term aftermath in Los Angeles. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2021:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09578-6. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandan J.S., Taylor J., Bradbury-Jones C., Nirantharakumar K., Kane E., Bandyopadhyay S. COVID-19: A public health approach to manage domestic violence is needed. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(6):e309. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30112-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Di Franco M., Martines G.F., Carpinteri G., Trovato G., Catalano D. Domestic violence detection amid the COVID-19 pandemic: the value of the WHO questionnaire in Emergency Medicine. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa333/6055562. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner M., Nivette A. Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation; New York: 2020. Violence and the pandemic – Urgent questions for research.https://www.hfg.org/Violence%20and%20the%20Pandemic.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Engel L., Farley E., Tilley J. Council on Criminal Justice; Washington, D.C.: November 2020. COVID-19 and Opioid Use Disorder. [Google Scholar]

- *Evans D.P., Hawk S.R., Ripkey C.E. Domestic violence in Atlanta, Georgia before and during COVID-19. Violence and Gender. 2021 doi: 10.1089/vio.2020.0061. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fana M., Torrejón Pérez S., Fernández-Macías E. Employment impact of Covid-19 crisis: from short term effects to long terms prospects. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2020;47:391–410. doi: 10.1007/s40812-020-00168-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Florido A. National Public Radio; 2021, January 26. Puerto Rico's Governor declares state of emergency over gender violence.https://www.npr.org/2021/01/26/960855914/puerto-ricos-governor-declares-state-of-emergency-over-gender-violence [Google Scholar]

- Galea S., Merchant R.M., Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2020;180(6):817–818. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Gerell M., Kardell J., Kindgren J. Minor covid-19 association with crime in Sweden. Crime Science. 2021;9(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40163-020-00128-3. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Gosangi B., Park H., Thomas R., Gujrathi R., Bay C.P., Raja A.S., Seltzer S.E., et al. Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during COVID-19 pandemic. Radiology. 2021;298(1):E38–E45. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamadani J.D., Hasan M.I., Baldi A.J., Hossain S.J., Shiraji S., Bhuiyan M.S.A.…Pasricha S.R. Immediate impact of stay-at-home orders to control COVID-19 transmission on socioeconomic conditions, food insecurity, mental health, and intimate partner violence in Bangladeshi women and their families: An interrupted time series. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(11):e1380–e1389. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30366-1. Nov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hsu L.-C., Henke A. COVID-19, staying at home, and domestic violence. Review of Economics of the Household. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11150-020-09526-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetelina K.K., Knell G., Molsberry R.J. Changes in intimate partner violence during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. Injury Prevention. 2021 doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043831. https://injuryprevention.bmj.com/content/early/2020/09/01/injuryprev-2020-043831 forthcoming. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashen J., Glynn S.J., Novello A. Center for American Progress; 2020, October 30. How COVID-19 sent women’s workforce progress backward.https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2020/10/30/492582/covid-19-sent-womens-workforce-progress-backward/ [Google Scholar]

- Knaul F.M., Bustreo F., Horton R. Countering the pandemic of gender-based violence and maltreatment of young people: The Lancet commission. The Lancet. 2020;395(Issue 10218):P98–P99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Leslie E., Wilson R. Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. Journal of Public Economics. 2020;189:104241. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *McLay M.M. When “Shelter-in-Place” Isn’t Shelter that’s safe: a rapid analysis of domestic violence case differences during the COVID-19 pandemic and stay-at-home orders. Journal of Family Violence. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00225-6. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal S., Singh T. Gender-based violence during COVID-19 pandemic: A mini-review. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health. 2020;1:4. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2020.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *De la Miyar, Balmori J.R., Hoehn-Velasco L., Silverio-Murillo A. Druglords don’t stay at home: COVID-19 pandemic and crime patterns in Mexico City. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2021:101745. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101745. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M.…Stewart L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mohler G., Bertozzi A.L., Carter J., Short M.B., Sledge D., Tita G.E.…Brantingham P.J. Impact of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on crime in Los Angeles and Indianapolis. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2020;68 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A., Boxall H. Social isolation, time spent at home, financial stress, and domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Australian Institute of Criminology. No. 609 (October, 2020) 2020. https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/ti609_social_isolation_DV_during_covid-19_pandemic.pdf (accessed February 7, 2021)

- *Nix J., Richards T.N. The immediate and long-term effects of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on domestic violence calls for service across six U.S. jurisdictions. Police Practice and Research. 2021;10:1080. [Google Scholar]

- OECD . OECD Publishing; Paris: 2020. Lessons for Education from COVID-19: A Policy Maker’s Handbook for More Resilient Systems. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson D. Investigating the increase in domestic violence post-disaster: An Australian case study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2019;34(11):2333–2362. doi: 10.1177/0886260517696876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick S.W., Henkhaus L.E., Zickafoose J.S., Lovell K., Halvorson A., Loch S.…Davis M.M. Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-016824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Payne J., Morgan A. 2020. COVID-19 and violent crime: A comparison of recorded offence rates and dynamic forecasts (ARIMA) for March 2020 in Queensland, Australia. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Pentaraki M., Speake J. Domestic violence in a COVID-19 context: Exploring emerging issues through a systematic analysis of the literature. Open Journal of Social Sciences. 2020;8(10):193. [Google Scholar]

- *Perez-Vincent S.M., Carreras E., Gibbons M.A., Murphy T.E., Rossi M.A. Inter-American Development Bank; Washington, DC, USA: 2020. COVID-19 lockdowns and domestic violence. [Google Scholar]

- Peterman A., O’Donnell M. Center for Global Development (December); 2020. COVID-19 and violence against women and children: A third research round Up for the 16 days of activism.https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/covid-and-violence-against-women-and-children-three.pdf (accessed February 7, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Pfitzner N., Fitz-Gibbon K., Meyer S., True J. Responding to Queensland's ‘shadow pandemic’ during the period of COVID-19 restrictions: practitioner views on the nature of and responses to violence against women. 2020. Monash University Report. [DOI]

- Phelps C., Sperry L.L. Children and the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research. Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(S1):S73. doi: 10.1037/tra0000861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A.R., Farrington D.P., Welsh B.C., Tremblay R., Jennings W.G. Effects of early family/parent training programs on antisocial behavior and delinquency. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2009;5(2):83–120. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A.R., Jennings W.G., Farrington D.P. On the malleability of self-control: Theoretical and policy implications regarding a general theory of crime. Justice Quarterly. 2010;27(6):803–834. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A.R., Jennings W.G., Diamond B., Reingle J.M. A systematic review of age, sex, ethnicity, and race as predictors of violent recidivism. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2015;59(1):5–26. doi: 10.1177/0306624X13514733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A.R., Jennings W.G., Diamond B., Farrington D.P., Tremblay R.E., Welsh B.C., Reingle Gonzalez J.M. A meta-analysis update on the effects of early family/parent training programs on antisocial behavior and delinquency. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2016;12(2):229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A.R., Jennings W.G., Farrington D.P., Diamond B., Reingle Gonzalez J.M. A meta-analysis update on the effectiveness of early self-control improvement programs to improve self-control and reduce delinquency. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2016;12(2):249–264. [Google Scholar]

- *Piquero A.R., Riddell J.R., Bishopp S.A., Narvey C., Reid J.A., Piquero N.L. Staying home, staying safe? A short-term analysis of COVID-19 on Dallas domestic violence. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2020;45(4):601–635. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09531-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ravindran S., Shah M. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Unintended consequences of lockdowns: Covid-19 and the shadow pandemic. No. w27562. Working Paper. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Rhodes H.X., Petersen K., Lunsford L., Biswas S. COVID-19 resilience for survival: occurrence of domestic violence during lockdown at a rural American college of surgeons verified level one trauma center. Cureus. 2021;12(8) doi: 10.7759/cureus.10059. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld R., Abt T., Lopez E. D.C. Council on Criminal Justice; Washington, D.C.: January 2021. (2021). Pandemic, Social Unrest, and Crime in U.S. Cities: 2020 Year-End Update. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez O.R., Vale D.B., Rodrigues L., Surita F.G. Violence against women during the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2020;151(2):180–187. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasser Modestino A. Coronavirus child-care crisis will set women back a generation. The Washington Post. 2020, July 29. https://www.washingtonpost.com/us-policy/2020/07/29/childcare-remote-learning-women-employment/

- Shamseer L., Moher D., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M.…Stewart L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappe A. Working mothers are quitting to take care of their kids, and the US job market may never be the same. 2020, August 19. https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/19/economy/women-quitting-work-child-care/index.html CNN.

- Wenhma C., Smith J., Morgan R. COVID-19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak. The Lancet. 2020;395(Issue 10227):P846–P848. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom C.S. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989;244(4901):160–166. doi: 10.1126/science.2704995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood L., Schrag R.V., Baumler E., et al. On the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic: Occupational experiences of the intimate partner violence and sexual assault workforce. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0886260520983304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]