This cohort study measures the adherence to the American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP) palliative care guidelines among patients with serious illness at a level I trauma center in the United States.

Key Points

Question

What is the adherence to the American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program palliative care guidelines at a level I US trauma center as measured by the rate of goals of care (GOC) discussions by the trauma team with patients with serious illness?

Findings

In this cohort study of 486 adult trauma patients with serious illness, 18.9% had documented GOC within 72 hours of admission and 25.5% during the overall hospitalization. Completion of the GOC was significantly associated with the presence of mechanical ventilation and multiple indicators of serious illness.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest a need for system-level interventions to ensure best practices and may inform strategies to measure and improve trauma service quality in palliative care.

Abstract

Importance

The American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP) guidelines encourage trauma service clinicians to deliver palliative care in parallel with life-sustaining treatment and recommend goals of care (GOC) discussions within 72 hours of admission for patients with serious illness.

Objective

To measure adherence to TQIP guidelines–recommended GOC discussions for trauma patients with serious illness, treated at a level I trauma center in the US.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study included 674 adults admitted to a trauma service center for 3 or more days between December 2019 and June 2020. The medical records of 486 patients who met the criteria for serious illness using a consensus definition adapted to the National Trauma Data Bank were reviewed for the presence of a GOC discussion. Patients were divided into 2 cohorts based on admission before or after the guidelines were incorporated into the institutional practice guidelines on March 1, 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were GOC completion within 72 hours of admission and during the overall hospitalization. Patient and clinical factors associated with GOC completion were assessed. Other palliative care processes measured included palliative care consultation, prior advance care planning document, and do-not-resuscitate code status. Additional end-of-life processes (ie, comfort care and inpatient hospice) were measured in a subset with inpatient mortality.

Results

Of 674 patients meeting the review criteria, 486 (72.1%) met at least 1 definition of serious illness (mean [SD] age, 60.9 [21.3] years; mean [SD] Injury Severity Score, 16.9 [12.3]). Of these patients, 328 (67.5%) were male and 266 (54.7%) were White. Among the seriously ill patients, 92 (18.9%) had evidence of GOC completion within 72 hours of admission and 124 (25.5%) during the overall hospitalization. No differences were observed between patients admitted before and after institutional guideline publication in GOC completion within 72 hours (19.0% [47 of 248 patients] vs 18.9% [45 of 238]; P = .99) or during the overall hospitalization (26.2% [65 of 248 patients] vs 24.8% [59 of 238]; P = .72). After adjusting for age, GOC completion was found to be associated with the presence of mechanical ventilation (odds ratio [OR], 6.42; 95% CI, 3.49-11.81) and meeting multiple serious illness criteria (OR, 4.07; 95% CI, 2.25-7.38).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this cohort study suggest that, despite the presence of national guidelines, GOC discussions for patients with serious illness were documented infrequently. This study suggests a need for system-level interventions to ensure best practices and may inform strategies to measure and improve trauma service quality in palliative care.

Introduction

Palliative care is a type of care aimed at improving the quality of life and reducing suffering for seriously ill patients and their families. Trauma patients who are seriously ill owing to their injuries or underlying conditions have important palliative care needs because they face a higher risk of complications, functional disability, and mortality.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 The American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP) palliative care best practices guidelines emphasize palliative care delivery by the trauma team in parallel with life-sustaining trauma care.9 The guidelines recommend trauma teams initiate goals of care (GOC) discussions within 72 hours of admission for patients with potentially life-threatening or disabling injuries as well as preinjury serious illness.

Previous work measuring primary palliative care (ie, care provided by the primary treating team) and guideline adherence among trauma patients has largely been limited to older adults, those admitted with life-threatening trauma, or decedents, rather than those with broader serious illness for whom it benefits.10,11,12 Therefore, we sought to identify a cohort with serious illness by using standardized data elements routinely abstracted for the National Trauma Database (NTDB)13 to measure performance in palliative care process measures relevant to the guidelines, consistent with the existing national benchmarking and trauma registries.

Our primary objective was to evaluate adherence to the TQIP guidelines at a single-institution level I trauma center using GOC completion for patients admitted with serious illness as the key palliative care performance measure. In addition, we aimed to describe patterns in overall GOC completion to characterize primary palliative care delivery and identify potential unmet care needs.

Methods

Data Source and Sample of Seriously Ill Patients

This retrospective observational cohort study comprised adult patients admitted to a trauma service at a single-center academic level I trauma center between December 2019 and June 2020. This period represents the 3 months before and after formal inclusion of the TQIP guidelines into the institution’s trauma guidelines on March 1, 2020. Admissions were identified using the institution’s trauma registry, which matches and/or maps most of its fields to the National Trauma Data Standard for submission to the NTDB. Patients were included if they had a hospital length of stay (LOS) of at least 3 days to allow for identification of GOC discussions until the recommended 72 hours. Patients admitted or transferred to another service on or before the third calendar day were excluded. This protocol was approved by the University of California, Davis Institutional Review Board, and a waiver of consent was obtained because of the retrospective nature of the investigation.

The TQIP guidelines do not explicitly outline what constitutes serious illness in trauma because defining serious illness as a denominator for quality measurement in palliative care delivery remains a challenge and an area of active clinical research. Conceptually, “serious illness” has been defined as a health condition that carries a high risk of mortality AND either negatively affects a person’s daily function or quality of life OR excessively strains their caregivers.14 Lee et al15 developed a consensus definition for serious illness in surgical patients that includes a set of 11 conditions and health states including critical trauma that was applied to Medicare claims in patients undergoing major surgery in 2017.16

We operationalized the Lee consensus definition by mapping it to preexisting conditions already tracked in the institutional trauma registry and matching NTDB operational definitions (Table 1).9 Additional medical record abstraction was required for 2 serious illness indicators: American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class IV or V and admission from skilled nursing home residency. Frailty was defined as 2 or more points on the modified 5-item Frailty Index, a simple validated scale applied to the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data, calculated by adding a point for the presence of each of the following 5 factors: congestive heart failure, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dependent functional health status, and hypertension requiring medication.17,18

Table 1. Modifications to the Surgical Serious Illness Consensus Definition and Relevant Data Sources.

| Criterion No. | Lee et al15 definitiona | Adapted definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ASA risk score: class IV or V | No modification(s)b |

| 2 | Vulnerable elder (adult aged >84 y or adult aged >64 y with any functional or cognitive disability) | Vulnerable elder (adult aged >84 y or adult aged >64 y with functionally dependent health status or history of stroke or CVA or of dementia)c |

| 3 | Advanced cancer (stage III or IV solid cancers and hematologic malignancies) and ≥1 hospitalization in prior year | Disseminated cancerc |

| 4 | Oxygen-dependent pulmonary disease | COPDc |

| 5 | CHF with any all-cause hospitalization or ≥2 ED visits in past 6 mo | CHFc |

| 6 | Cirrhosis with any CTP class or MELD score | No modification(s)c |

| 7 | ESKD on dialysis or eligible for dialysis | No modification(s)c |

| 8 | Dementia with impaired daily function and ≥1 hospitalization in prior year | Dementiac |

| 9 | Frailty (left undefined) | ≥2 Points on the modified 5-item Frailty Indexd |

| 10 | Trauma with: (1) severe TBI with an AIS score ≥3, or a GCS score of 3-8; or (2) critical injury (ISS >25 and/or >24-h ICU admission) | No modification(s)c |

| 11 | Nursing home resident | Admitted from skilled nursing facilityb |

Abbreviations: AIS, Abbreviated Injury Scale; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; ED, emergency department; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ICU, intensive care unit; ISS, Injury Severity Score; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

The use of italics for some words indicates that these original qualifiers were removed in the adapted definition.

Additional medical record review or abstraction required outside of the trauma registry or National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB).

NTDB-defined field(s).

The Frailty Index is based on National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data and gives 1 point each for COPD, CHF, dependent functional status, hypertension requiring medication, and diabetes.

Records for patients meeting at least 1 of the 11 adapted serious illness consensus criteria were then manually reviewed for evidence of documented GOC discussions conducted by the trauma team (eFigure in the Supplement).

Identification of GOC Discussions

A GOC discussion was defined broadly to reflect the guidelines and included discussions about code status or identification of a surrogate decision-maker. The date and time of the earliest evident GOC discussion completed by a trauma service clinician from arrival to the emergency department was recorded. Clinical notes were reviewed until hospital day 30 (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

In an iterative process across 15 clinical records and expanding from terms in previously established palliative care natural language processing codebooks,10,19 a comprehensive free-text search method of the Epic electronic health record (EHR) was established using a list of key words and phrases clinicians use (eg, goals of care, discuss, meeting, and DNR [do not resuscitate]). The standardized combined terms queried using the Epic search bar resulted in a narrower list of unstructured notes with highlighted keywords of interest, enabling a more accurate and efficient manual review (by authors J.P., R.R., and S.R.).

Outcomes Measured

Adherence to TQIP palliative care best practices guidelines was evaluated by evidence of early GOC discussion completion within 72 hours of admission. Overall GOC completion during the overall hospitalization was also assessed. Demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, and preferred language) and hospitalization characteristics (mechanism of injury, use of mechanical ventilation, LOS, and discharge disposition including inpatient mortality) were collected. Race and ethnicity were defined by NTDB fields, classified based on self-report, and were included to characterize the sample and study their association with GOC completion. Mechanism of injury was identified through the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) primary external cause codes, classified based on the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention matrix, and further categorized as penetrating (firearm, cut, or pierce), fall, motor vehicle traffic (occupant, motorcyclist, pedal cyclist, or pedestrian), or other blunt injury (other land transport, struck by or against).

Other secondary palliative care processes measured included palliative care consultation, obtainment of preexisting advance care planning (ACP) documents (ie, physician orders for life-sustaining treatment, advance directive, or living will), and do-not-resuscitate (DNR) code status order during the overall hospitalization. Goals of care completion, palliative care consultation, and end-of-life processes (ie, comfort care order and inpatient hospice utilization) were additionally assessed in the subset of patients with inpatient mortality.

Statistical Analysis

We compared demographics and clinical factors by GOC completion using χ2, Fisher exact, or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, as appropriate. Differences in GOC completion in patients admitted before and after institutional publication of the guidelines (March 1, 2020) were compared using the 2-proportions z test. Multivariable logistic regression was used to evaluate factors associated with GOC completion. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 932 patients were hospitalized for at least 3 days during the study period (December 2019 to June 2020), 258 (27.7%) of whom were excluded because of admission or transfer to another service. Of the remaining 674 patients, 486 (72.1%) met at least 1 adapted consensus definition of serious illness and were further reviewed for GOC completion (eFigure in the Supplement). The mean (SD) age of the cohort of patients with serious illness was 60.9 (21.3) years and the majority were male (328 [67.5%]) and White (266 [54.7%]). Most patients (253 [52.1%]) experienced injury by fall, the mean (SD) Injury Severity Score was 16.9 (12.3), and 124 patients (25.5%) required mechanical ventilation. The most prevalent indicators of serious illness were critical trauma (341 patients [70.2%]), frailty (193 [39.7%]), and being a vulnerable elderly individual (aged >84 years or aged >64 years with functionally dependent health status or a history of stroke or cerebrovascular accident or of dementia) (156 [32.1%]). Most patients (292 [60.1%]) also had 2 or more serious illness indicators. The median (IQR) LOS was 7 days (4-12 days), and 196 patients (40.3%) were discharged to a nonhome facility (ie, long-term acute care, long-term care, skilled nursing, or board and care facility). In-hospital mortality was 4.9% (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Patient groups admitted before vs after TQIP guidelines were integrated into the institutional guidelines on March 1, 2020, were evenly split (preguideline group, 248 patients and postguideline group, 238 patients). Patients admitted in the preguideline vs postguideline period had a lower prevalence of ASA class IV or V (18.1% vs 27.3%; P = .02) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Differences in discharge disposition were observed, with higher rates of nonhome discharge (43.1% vs 37.4%; P = .02) and inpatient death (6.9% vs 2.9%; P = .02) in patients admitted before guideline inclusion vs after. Otherwise, there were no other significant between-group differences.

GOC Performance and Associated Characteristics

Among the patients with serious illness, 92 (18.9%) had documented evidence of early GOC completion within 72 hours of admission in adherence with the TQIP guidelines and 124 (25.5%) had evidence of any GOC completion during the overall hospitalization. No differences were observed between the preguideline vs postguideline groups in GOC completion within 72 hours (19.0% [47 of 248 patients] vs 18.9% [45 of 238]; P = .99) or overall (26.2% [65 of 248 patients] vs 24.8% [59 of 238]; P = .72) (eFigure in the Supplement).

On bivariate analysis, seriously ill patients with documented GOC were found to be older (mean [SD] age, 72.8 [20.1] vs 56.9 [20.2] years; P < .001). Patients with evidence of GOC completion had higher rates of fall as a mechanism (71.0% vs 45.6%; P < .001), mechanical ventilation use (34.7% vs 22.4%; P = .007) and 2 or more indicators of serious illness (87.1% vs 50.8%; P < .001). They also had higher rates of nonhome discharge (51.6% vs 36.5%; P < .001) and higher inpatient mortality (17.7% vs 0.6%; P < .001). Goals of care completion was also associated with higher rates of other palliative care processes, such as palliative care consultation (37.9% vs 1.1%; P < .001), preexisting ACP document(s) (20.2% vs 9.1%; P = .001), and DNR code status (42.7% vs 0.8%; P < .001). No differences were observed in GOC completion by sex, race, ethnicity, or preferred language (Table 2).

Table 2. Patient Characteristics of Seriously Ill Sample Stratified by GOC Completion.

| Variable | No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 486) | GOC completion (n = 486) | |||

| Incomplete (n = 362) | Complete (n = 124) | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 60.9 (21.3) | 56.9 (20.2) | 72.8 (20.1) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 328 (67.5) | 252 (69.6) | 76 (61.3) | .09 |

| Female | 158 (32.5) | 110 (30.4) | 48 (38.7) | |

| Race | ||||

| African American or Black | 41 (8.4) | 27 (7.5) | 14 (11.3) | .06 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 24 (4.9) | 19 (5.2) | 5 (4.0) | |

| White | 266 (54.7) | 191 (52.8) | 75 (60.4) | |

| Othera | 128 (26.3) | 106 (29.3) | 21 (16.9) | |

| Unknown or not reported | 27 (5.6) | 19 (5.2) | 9 (7.3) | |

| Ethnicity Hispanic or Latino | 71 (14.6) | 57 (15.7) | 14 (11.3) | .36 |

| Non-English, preferred language | 34 (7.0) | 24 (6.6) | 10 (8.1) | .59 |

| Mechanism of injury | ||||

| Penetrating (firearm, cut, or pierce) | 52 (10.7) | 48 (13.3) | 4 (3.2) | <.001 |

| Fall | 253 (52.1) | 165 (45.6) | 88 (71.0) | |

| Motor vehicle traffic (occupant, motorcyclist, pedal cyclist, or pedestrian) | 147 (30.3) | 120 (33.2) | 27 (21.8) | |

| Other blunt injury | 34 (7.0) | 29 (8.0) | 5 (4.0) | |

| ISS, mean (SD) | 16.9 (12.3) | 16.3 (10.7) | 18.4 (16.1) | .97 |

| Mechanical ventilation present | 124 (25.5) | 81 (22.4) | 43 (34.7) | .007 |

| Presence of serious illness | ||||

| ASA class IV or V | 110 (22.6) | 70 (19.3) | 40 (32.3) | .003 |

| Vulnerable elderly adult | 156 (32.1) | 87 (24.0) | 69 (55.6) | <.001 |

| Aged >84 y | 75 (15.4) | 34 (9.4) | 41 (33.1) | <.001 |

| Aged >64 y with disability | 81 (16.7) | 53 (14.6) | 28 (22.6) | .04 |

| Disseminated cancer | 13 (2.7) | 5 (1.4) | 8 (6.5) | .006 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 68 (14.0) | 42 (11.6) | 26 (21.0) | .01 |

| Congestive heart failure | 58 (11.9) | 32 (8.8) | 26 (21.0) | <.001 |

| Cirrhosis | 26 (5.3) | 19 (5.2) | 7 (5.6) | .87 |

| End-stage kidney disease | 12 (2.5) | 9 (2.5) | 3 (2.4) | >.99 |

| Dementia | 56 (11.5) | 22 (6.1) | 34 (27.4) | <.001 |

| Frailty | 193 (39.7) | 126 (34.8) | 67 (54.0) | <.001 |

| Critical trauma | 341 (70.2) | 249 (68.8) | 92 (74.2) | .26 |

| Severe traumatic brain injury | 170 (35.0) | 125 (34.5) | 45 (36.3) | .72 |

| AIS score ≥3 | 170 (35.0) | 125 (34.5) | 45 (36.3) | .72 |

| GCS score 3-8 | 17 (3.5) | 3 (0.8) | 14 (11.3) | <.001 |

| Critical injury | 293 (60.3) | 209 (57.7) | 84 (67.7) | .05 |

| ISS >25 | 91 (18.7) | 65 (18.0) | 26 (21.0) | .46 |

| ICU length of stay >24 h | 280 (57.6) | 196 (54.1) | 84 (67.7) | .008 |

| Admitted from skilled nursing facility | 11 (2.3) | 7 (1.9) | 4 (3.2) | .48 |

| ≥2 Indicators of serious illness | 292 (60.1) | 184 (50.8) | 108 (87.1) | <.001 |

| Palliative care consultation | 51 (10.5) | 4 (1.1) | 47 (37.9) | <.001 |

| Prior advance care planning document | 58 (11.9) | 33 (9.1) | 25 (20.2) | .001 |

| DNR code status | 56 (11.5) | 3 (0.8) | 53 (42.7) | <.001 |

| Hospital length of stay, median (IQR), d | 7 (4-12) | 6 (4-10) | 10 (5-18) | <.001 |

| Discharge disposition | ||||

| Home | 224 (46.1) | 193 (53.3) | 31 (25.0) | <.001 |

| Nonhome facility | 196 (40.3) | 132 (36.5) | 64 (51.6) | |

| Died | 24 (4.9) | 2 (0.6) | 22 (17.7) | |

| Other | 42 (8.6) | 35 (9.7) | 7 (5.6) | |

Abbreviations: DNR, do not resuscitate; GOC, goals of care. Other abbreviations are explained in the first footnote to Table 1.

Other included American Indian or those specified as “other race” in line with the National Trauma Database’s element values for race.13

In a multivariable analysis after adjusting for age, mechanical ventilation requirement (odds ratio [OR], 6.42; 95% CI, 3.49-11.81) and having 2 or more serious illness indicators (OR, 4.07; 95% CI, 2.25-7.38) were associated with increased odds of GOC completion (Table 3).

Table 3. Logistic Regression of GOC Completion (GOC Complete vs GOC Incomplete).

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | P value | Adjusteda | P value | |

| Fall as mechanism of injury | 2.92 (1.88-4.53) | <.001 | 1.04 (0.59-1.83) | .90 |

| Mechanical ventilation present | 1.84 (1.18-2.87) | .007 | 6.42 (3.49-11.81) | <.001 |

| Multiple vs single serious illness indicators | 6.53 (3.72-11.48) | <.001 | 4.07 (2.25-7.38) | <.001 |

| Prior advanced care planning document | 2.52 (1.43-4.44) | .001 | 1.29 (0.71-2.36) | .41 |

Abbreviations: GOC, goals of care; OR, odds ratio.

Adjusted by age.

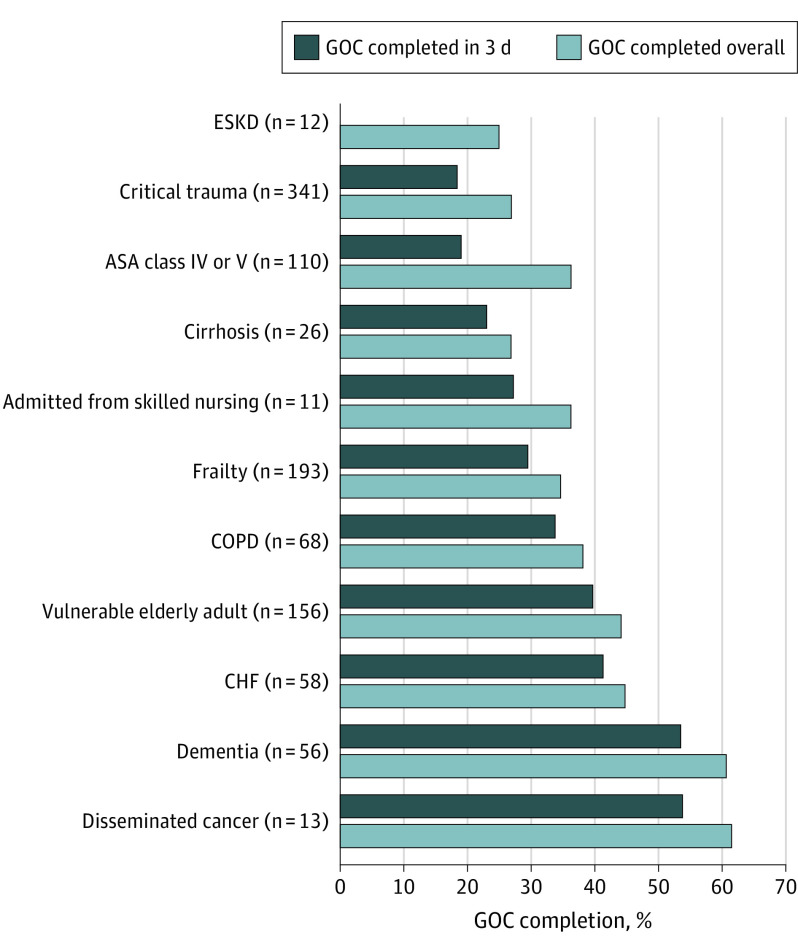

GOC Performance by Indicators of Serious Illness

The Figure compares performance across the individual serious illness criteria by early and overall GOC completion. The highest-performing serious illness indicators, that is, those in which most patients who met that respective consensus definition had evidence of a GOC discussion, were disseminated cancer (8 of 13 patients [61.5%]) and dementia (34 of 56 patients [60.7%]). Goals of care discussions were identified in 69 of 156 vulnerable elders (44.2%). The poorest-performing indicators by GOC completion were end-stage kidney disease (3 of 12 patients [25.0%]), cirrhosis (7 of 26 patients [26.9%]), and critical trauma (92 of 341 patients [27.0%]). In the case of critical trauma, however, performance varied widely by its consensus definition’s individual components. For example, whereas patients meeting criteria for severe traumatic brain injury by the Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3 to 8 had a GOC completion rate of 82.4% (14 of 17 patients), only 45 of 170 patients (26.5%) with an Abbreviated Injury Scale score of 3 or higher had a completed GOC documentation.

Figure. Comparison of Goals of Care (GOC) Completion Across Individual Serious Illness Criteria.

On the y-axis, the numbers in parentheses denote the number of patients with the particular serious illness. Vulnerable elderly adult was defined as individuals older than 84 years and individuals older than 64 years who had a functionally dependent health status or a history of stroke or cerebrovascular accident or of dementia. ASA indicates American Society of Anesthesiologists; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; and ESKD, end-stage kidney disease.

For most indicators of serious illness, early GOC performance fell relatively closely behind that of overall GOC completion. Conversely, no patients with end-stage kidney disease had evidence of a GOC discussion successfully completed within 72 hours. In addition, although 40 of 110 patients (36.4%) meeting ASA class IV or V had completed GOC, only approximately half of the GOCs (21 of 40 [52.5%]) were successfully completed within the recommended 72 hours. Considering patients with 2 or more serious illness indicators (n = 292), GOC discussions were completed early in 83 patients (28.4%) and overall, in 108 (37.0%).

Additional Palliative Care Performance Measures

The inpatient palliative care consultation rate for patients with serious illness was 10.5% (Table 2). Fifty-eight patients (11.9%) had evidence of a preexisting ACP document, 39 (67.2%) of which were uploaded to the EHR within 24 hours of hospitalization, in line with the TQIP guidelines. Of note, however, about half of these (20 [51.3%]) were already within the EHR system prior to the index encounter. A DNR code status was ordered at some point during the overall hospitalization for 56 patients (11.5%).

In the subset of patients with inpatient mortality (n = 24), nearly all had evidence of GOC completion (22 [91.7%]), with 17 completions (70.8%) occurring early. Although approximately two-thirds of the patients (16 [66.7%]) received palliative care consultation and 17 (70.8%) had comfort care orders in place at the time of death, only 3 patients (12.5%) died in inpatient hospice.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of patients with serious illness treated at a level I US trauma center, only 18.9% of the patients had documented evidence of GOC completion within 72 hours of admission in adherence with TQIP guidelines and 25.5% had evidence of any GOC completion during the overall hospitalization. GOC completion did not differ in the 3 months following integration in institutional trauma guidelines without any additional workflow modifications. GOC completion was associated with increased age, mechanical ventilation requirement, other palliative care processes (eg, palliative care consultation, prior ACP documents, and DNR code status) as well as the presence of 2 or more indicators of serious illness.

The results of this study are consistent with previous work evaluating adherence to the TQIP palliative care guidelines and expand the current literature by describing GOC performance for patients with a broader definition of serious illness. In a study by Lee et al,10 natural language processing–identified GOC discussions in all adult patients with life-threatening injuries occurred at a rate of 18% and code status clarification occurred in 27% of the admissions. In another single-institution study of trauma decedents, a family meeting was documented for 94% of the patients, with 57% of those meetings occurring early, in line with the TQIP guidelines. These data substantiate the gaps in early primary palliative care and underscore the need for system-level quality improvement interventions to support clinical guideline dissemination and implementation, such as automated clinical assessments or triggers to identify seriously ill patients on admission, EHR-based tools for accessible and standardized documentation, and clinician training in serious illness communication.

Greater than two-thirds (72.1%) of the patients in this cohort with an LOS of at least 3 days met the adapted consensus definition for serious illness. Our study did not aim to validate this definition, but rather use it as a starting point for objective performance measurement not otherwise currently performed nor possible using existing TQIP guidelines and NTDB covariates. Although analyzing GOC completion by indicators of serious illness could hold the potential to illustrate unmet palliative care needs and vulnerable subgroups, it is unclear in this study if some of the low or variable rates in GOC completion were due to true gaps in care delivery vs definitions that may not be sufficiently specific to capture the highest-risk patients in the trauma population. This stresses the ongoing need for rigorous methods to prospectively identify these surgical populations so that once they are more clearly defined, national standards for palliative care quality benchmarking and reporting requirements that reflect them could enable risk-adjusted comparisons across institutions and enhance the ability to improve palliative care in trauma centers in the United States. Nonetheless, it is important to note that patients are eligible for palliative care delivery at any stage of illness as opposed to hospice, which targets patients in their last months of life.20 The prevalence of serious illness, however defined, demands the integrative model of palliative care delivery stressed in the TQIP guidelines, whereby primary palliative care is delivered by the interdisciplinary team of trauma care clinicians and specialist or consultative palliative care provided by board-certified specialists is reserved for a minority of patients and families with more complex needs.21,22,23

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Our findings are limited by the retrospective design of this single-institution study. Our small sample size meant that we were likely unable to accurately estimate associations with GOC completion with certain sparse-data covariates. We sought to use already-collected registry data wherever possible for feasibility purposes. In mapping serious illness consensus criteria to preexisting conditions defined by the National Trauma Data Standard, qualifying conditions potentially key to the accurate diagnosis of several serious illness criteria were lost (eg, “…with hospitalization in the last year,” Table 1). This decision in design permitted less additional manual review in the already time-intensive chart abstraction. In addition, trauma patients are frequently transferred from outside hospitals and lost to follow-up, thereby making institutional review of these qualifiers difficult. The decision to identify frailty through the modified 5-item Frailty Index, which is repetitive of variables in the definition de novo by Lee et al15 and rather limited in comparison with alternative instruments for the detection of frailty syndrome, has similar trade-offs.24

We captured only the documented palliative care process measures. Our choice to identify only GOC discussions led by the trauma team additionally precluded identification of conversations by other specialty clinicians routinely involved in trauma care, but who otherwise were likely unaware of these guidelines. Anecdotally, reviewers noted that early GOC discussions were frequently related to conversations regarding code status limitations. Although qualitative classification of primary content in completed GOC discussions could have allowed us to better quantify these GOC characteristics, our primary interest was the earliest evident GOC discussion. More thorough and efficient thematic analysis could be achieved in the future through natural language processing.

Conclusions

In this retrospective cohort study of patients with serious illness, GOC discussions were documented infrequently despite the existing best practice guidelines. This study identified potential gaps in primary palliative care delivery for trauma patients at a single institution using a definition of serious illness in surgical patients as a denominator adapted to NTDB benchmarking. This work may guide strategies to better meet trauma patients’ palliative care needs in earlier stages of illness and measure care quality. It underscores the need for standardized approaches to GOC documentation and system-level interventions to support best practices as well as national consensus on more clearly defined and validated quality metrics in surgical palliative care to measure and ensure fidelity.

eFigure. Flow Diagram of Subject Selection and Goals of Care (GOC) Chart Review

eTable 1. Definition of Goals of Care and String of Epic Search Terms Used for Manual Review

eTable 2. Patient Characteristics Stratified by Admission Pre- Versus Post- Guideline Integration Into Institutional Trauma Guidelines

References

- 1.Bonne S, Schuerer DJE. Trauma in the older adult: epidemiology and evolving geriatric trauma principles. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(1):137-150. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2012.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joseph B, Pandit V, Zangbar B, et al. Validating trauma-specific frailty index for geriatric trauma patients: a prospective analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(1):10-17.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joseph B, Orouji Jokar T, Hassan A, et al. Redefining the association between old age and poor outcomes after trauma: the impact of frailty syndrome. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(3):575-581. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aziz HA, Lunde J, Barraco R, et al. Evidence-based review of trauma center care and routine palliative care processes for geriatric trauma patients: a collaboration from the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Patient Assessment Committee, the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Geriatric Trauma Committee, and the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Guidelines Committee. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86(4):737-743. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson GH, Hamlat CA, Rivara FP, Koepsell TD, Jurkovich GJ, Arbabi S. Long-term survival of adult trauma patients. JAMA. 2011;305(10):1001-1007. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lilley EJ, Scott JW, Weissman JS, et al. End-of-life care in older patients after serious or severe traumatic brain injury in low-mortality hospitals compared with all other hospitals. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(1):44-50. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maxwell CA, Mion LC, Mukherjee K, et al. Preinjury physical frailty and cognitive impairment among geriatric trauma patients determine postinjury functional recovery and survival. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(2):195-203. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joseph B, Pandit V, Khalil M, et al. Managing older adults with ground-level falls admitted to a trauma service: the effect of frailty. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(4):745-749. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP) . ACS TQIP palliative care best practices guidelines. October 2017. Accessed September 10, 2020. https://www.facs.org/media/g3rfegcn/palliative_guidelines.pdf

- 10.Lee KC, Udelsman BV, Streid J, et al. Natural language processing accurately measures adherence to best practice guidelines for palliative care in trauma. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(2):225-232.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhangu JK, Young BT, Posillico S, et al. Goals of care discussions for the imminently dying trauma patient. J Surg Res. 2020;246:269-273. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.07.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edsall A, Howard S, Dewey EN, et al. Critical decisions in the trauma intensive care unit: are we practicing primary palliative care? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;91(5):886-890. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American College of Surgeons . National Trauma Data Standard. Accessed January 12, 2022. https://www.facs.org/media/mkxef10z/ntds_data_dictionary_2022.pdf

- 14.Kelley AS, Bollens-Lund E. Identifying the population with serious illness: the “denominator” challenge. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(suppl 2):S7-S16. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee KC, Walling AM, Senglaub SS, Kelley AS, Cooper Z. Defining serious illness among adult surgical patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(5):844-850.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly MT, Sturgeon D, Harlow AF, Jarman M, Weissman JS, Cooper Z. Using Medicare data to identify serious illness in older surgical patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e101-e103. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tracy BM, Adams MA, Schenker ML, Gelbard RB. The 5 and 11 factor modified frailty indices are equally effective at outcome prediction using TQIP. J Surg Res. 2020;255:456-462. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.05.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chimukangara M, Helm MC, Frelich MJ, et al. A 5-item frailty index based on NSQIP data correlates with outcomes following paraesophageal hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(6):2509-2519. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5253-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lilley EJ, Lindvall C, Lillemoe KD, Tulsky JA, Wiener DC, Cooper Z. Measuring processes of care in palliative surgery: a novel approach using natural language processing. Ann Surg. 2018;267(5):823-825. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP)|NCHPC|National Coalition For Hospice and Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th Edition. Accessed January 12, 2022. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp/

- 21.Strand JJ, Billings JA. Integrating palliative care in the intensive care unit. J Support Oncol. 2012;10(5):180-187. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA. Interdisciplinary model for palliative care in the trauma and surgical intensive care unit: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation demonstration project for improving palliative care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11)(suppl):S399-S403. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237044.79166.E1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(1):17-23. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faller JW, Pereira DdN, de Souza S, Nampo FK, Orlandi FdS, Matumoto S. Instruments for the detection of frailty syndrome in older adults: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0216166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Flow Diagram of Subject Selection and Goals of Care (GOC) Chart Review

eTable 1. Definition of Goals of Care and String of Epic Search Terms Used for Manual Review

eTable 2. Patient Characteristics Stratified by Admission Pre- Versus Post- Guideline Integration Into Institutional Trauma Guidelines