Abstract

Objective: This article describes the EMPOWER study, a controlled trial aiming to determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an eHealth intervention to prevent common health problems and reduce presenteeism and absenteeism in the workplace. Intervention: The EMPOWER intervention spans universal, secondary and tertiary prevention and consists of an eHealth platform delivered via a website and a smartphone app designed to guide employees throughout different modules according to their specific profiles. Design: A stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial will be implemented in four countries (Finland, Poland, Spain and UK) with employees from small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and public agencies. Companies will be randomly allocated in one of three groups with different times at which the intervention is implemented. The intervention will last 7 weeks. Employees will answer several questionnaires at baseline, pre- and post-intervention and follow-up. Outcome measures: The main outcome is presenteeism. Secondary outcomes include depression, anxiety, insomnia, stress levels, wellbeing and absenteeism. Analyses will be conducted at the individual level using the intention-to-treat approach and mixed models. Additional analyses will evaluate the intervention effects according to gender, country or type of company. Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses [based on the use of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYS)] will consider a societal, employers’ and employees’ perspective.

Keywords: eHealth, comorbidity, mental health, employees, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, presenteeism

Introduction

Common mental conditions, such as stress-related disorders, depression and anxiety, account for about 40% of occupational disease cases and these conditions are largely treatable and preventable.1 In the case of depression, an estimated 36 workdays per individual are lost each year on average.2 The associated cost of depression in the workplace across the 27 member countries of the European Union (EU) is more than EUR 600 billion per year, and the majority of this cost (EUR 270 billion) is manifested in the form of absenteeism and presenteeism.3,4 In 2010, the cost for all anxiety disorders associated to absenteeism and premature mortality in Europe was estimated to be €88 billion.5 In the UK, for example, an equivalent of 9.9 million days were estimated to be lost in 2014/2015 due to work-related stress, depression or anxiety, representing 43% of all working days lost due to illness.6

A number of interventions have been developed to promote wellbeing and prevent or treat mental disorders in the workplace.7–9 These occupational interventions have traditionally focused on organizational structures, the reduction or elimination of psychosocial stressors at work and educational interventions.10,11 Other interventions with a more individualistic focus include physical activity interventions, contemplative interventions (e.g., mindfulness and meditation), resilience training and cognitive behaviour therapy-based interventions.11 Overall, the impact of these interventions on mental health outcomes, such as a decrease in levels of anxiety, depression and stress, has been shown to be positive, but with a small to moderate effect size.7–9 Studies about the effectiveness of workplace interventions on work-related outcomes, such as presenteeism and absenteeism, are scarce and yielded mixed results. Presenteeism, defined as the loss of work productivity in workers who are working while having a physical or psychological health problem, is often a hidden cost.4,12 Several studies have operatized presenteeism as the time spent at work with decreased productivity due to the presence of physical and/or mental health problems.12 On the other hand, absenteeism is defined as the time that a worker is away from work due to illness or disability.12 Both absenteeism and presenteeism are associated with a decrease in work productivity10 and have been directly related to mental health problems.13 A recent meta-analysis based on 19 randomized control trials (RCT) that implemented workplace interventions aimed at improving work-related outcomes10 reported a significant positive reduction of absenteeism, but weak evidence for effectiveness in improving productivity. Specific interventions aimed at promoting health and wellbeing in the workplace have also been linked to beneficial effects on presenteeism.14 Several components of the intervention might affect the effectiveness. There is evidence for successful components of the intervention on improving presenteeism, such as screening workers prior to intervention, delivering tailored interventions, multimodal versus single interventions, or improving supervisor/manager’s knowledge regarding mental health in the workplace.11,14 Delivering interventions to improve mental health in the workplace through accessible digital technologies is a promising approach. Attempts to implement interventions by means of digital technologies indicate a positive impact on primary outcomes related to healthy lifestyles, but modest positive effects in reducing overall mental health problems.15,16 This might be associated with the fact that most eHealth interventions focus on a single mental health condition and neglect comorbidity, particularly in the case of common mental disorders.7 Both higher direct and indirect costs of physical and mental comorbidity, compared with single conditions, have been recognized, with the indirect costs due to increased levels of absenteeism and presenteeism.17 There is also a lack of rigorously conducted large-scale RCT using standardized clinical instruments.18 Additionally, the use of digital technologies to deliver interventions faces high drop-out rates19 and the problem of identifying participants at risk for mental disorders.20 Nevertheless, the interest of employers from small and medium enterprises (SMEs) – where resources to be allocated to the promotion and preventive programs might be insufficient21-on low-cost digital resources for improving mental health is considerable.

Although effective and cost-effective interventions in the workplace are available,22,23 the implementation of these interventions faces several barriers. First, mental health and wellbeing are rarely highly prioritized by employers and operational demands limit the resources available for mental health and wellbeing employee’s programs.24 This is especially true for SMEs, which represent the majority of all enterprises in the EU but have very limited resources to implement these health promotion programs.25–27 Another sector with limited resources in need for implementing health promotion programs is the public sector. Indeed, employees in the public sector have been shown to experience higher levels of stress, anxiety and depression when compared with private sector employees.28–30 For example, in a large population-based cohort of young Swedish employees it was found that public sector workers had an elevated risk of sickness absence due to common mental disorders, compared with private sector employees.30 Additionally, the cost associated with poor mental health seems to be disproportionally borne by the public sector in the form of absenteeism and presenteeism.31–34 Thus, there is a need for effective and cost-effective interventions addressing mental health in these sectors. Second, mental health programs are usually reactive, driven by staff or experience and not proactive and preventive.24,31,35 Third, the significance of good mental health at the workplace is not always appreciated, in part because it is difficult to measure the impact of workplace wellbeing on business performance.31,36 Fourth, although cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and mindfulness programs have been shown to have good results in addressing psychosocial risk factors and mental disorders37 these findings are not conclusive. Information on multi-modal interventions is still scarce.38 Fifth, it has been shown that digital interventions that ensure anonymity and are guided according to the users’ needs are associated to higher engagement.20 Next, stigma against people with mental illness might negatively affect participation in this type of intervention.39 Although anti-stigma interventions targeting the general population and workplace settings have been implemented, there is room for improvement.40 In particular, studies are needed to explore the extent to which changes in employees’ and employers’ attitudes, knowledge and behaviours have an effect on the rate with which people with mental health problems seek help and seek it out earlier. Finally, cultural adaptation of workplace interventions is one of the key elements related to a successful implementation, with better-expected outcomes for linguistically and culturally adapted interventions41 and those considering elements of organizational cultures.26 There is also evidence for a moderate effect of culturally adapted e-mental health interventions on reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms, compared with not culturally adapted interventions.42 Additionally, cross-country differences in health systems, applied work interventions and work-related policies might also imply variation in the effectiveness and implementation of workplace interventions across countries.43

To address these demands, we developed the EMPOWER platform, a multi-modal and integrative eHealth intervention aimed at reducing mental health problems in the workplace and improving employees’ wellbeing. EMPOWER was funded by the European Commission (EC), has been especially designed for SMEs and will undergo a rigorous evaluation of its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in an RCT using stepped-wedge trial design (SWTD). The objective of this study protocol is to describe the RCT, which will be conducted in SMEs and public sector organizations in four countries: Finland, Poland, Spain and the United Kingdom (UK). These countries represent different European welfare and health service models: the Scandinavian model (Finland), characterized by protective and universal regimes in terms of welfare provision; the Mediterranean model (Spain), with a fragmented system of welfare provision, and strong reliance on family and charitable sector; the Eastern European model (Poland), with an underdeveloped welfare system but strong labour market institutions and solid industrial economy; and the Anglo–Saxon model (UK), based on a National Health Service (NHS) providing medical treatments to all at no cost, and a welfare system with high social stratification.44

By minimally relying on professionals for implementation, the intervention is expected to become easily accessible to SMEs and many other types of institutions, such as public agencies, and will not incur a substantial financial burden. Additionally, by focusing on the individual and by relying on using online tools, the highest standards of confidentiality can be achieved.

Material and methods

Intervention

The EMPOWER intervention is a multi-modal and integrative eHealth platform aimed at promoting health and reducing the negative impact of mental health problems in the workplace. It incorporates a three-tiered intervention structure: universal (primary) prevention; targeted (secondary) prevention and tertiary prevention and addresses the following six domains: improving awareness of mental health problems and reducing stigma (primary prevention); reducing psychosocial risk factors in the workplace (primary prevention); improving wellbeing and reducing psychological symptoms (primary and secondary prevention); ensuring early detection of mental disorders (secondary prevention); promoting healthy behaviours and lifestyles (primary prevention); and facilitating early return to work and working with symptoms (tertiary prevention).

A detailed description of the design and rationale of the intervention will be published elsewhere.45 Briefly, the EMPOWER platform consists of a website and a mobile application. The website is public, and it contains an awareness campaign about mental health and general psychoeducational material on psychosocial problems at the workplace addressed to employees. The anti-stigma campaign includes the following sections which provide information, examples and advice: What is a healthy workplace?; What is good mental health?; Why mental health matters; Workplace bullying; Types of mental health conditions; Workplace stress, “are they ok?”; Starting a conversation; Helping a workmate; Legal rights and responsibilities.

The mobile app is intended to be used through the smartphones, although it will be possible to be used via a website, with a unique username and password. The app contains: (a) a triage to identify stressful psychosocial working conditions; (b) a triage to identify presenteeism, absenteeism, mental and physical symptoms; (c) modules to promote wellbeing and mental health; and (d) a work functioning module. It follows a completely self-guided approach; thus, no health professionals are directly involved. However, during the RCT, participants will be provided with the contact details of the local research team in case they have any doubt or inquiry. During the RCT, participants in the intervention group will be able to use the app during 7 weeks.

Triage to identify stressful psychosocial working conditions

Through the app, employees will answer the mini-psychosocial stressors at work scale (Mini-PSWS), a reduced version of the psychosocial stressors at work scale.46 This screening tool contains 16 items and it is conceptually grounded in the typology of workplace stressors developed by the European Framework for Psychosocial Risks Management PRIMA-EF47 and supported by a large body of research which showed direct relationships between workplace stress and burnout, depression, anxiety, adjustment disorders, somatization, chronic fatigue, psychotropic drugs consumption and many others conditions.48,49

Employees will receive through the app a detailed and tailored report with recommendations based on their responses to the Mini-PSWS. Additionally, each employer will receive general information about occupational stress in their company based on clustered and anonymous scores of their employees and actions that can be taken to improve work conditions in the company. This information will only be provided if scores for 10 or more employees are computed. If this is not achieved, a generic advice will be provided to employers. Employers will get the report through a back-end system specially designed for this purpose. Access to the back-end system will be only granted to specific managers in each company or department and will require previous registration.

Triage to identify presenteeism, absenteeism, mental and physical symptoms

The second screening included in the app was designed using the following five assessment tools: (1) the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7)50 to assess users’ anxiety levels; (2) the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)51 to assess users’ depressive symptoms; (3) the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-15)52 to assess users’ physical health symptoms; (4) part of the Checklist of Medical Conditions; 53 finally (5) combinations of these tools to address physical and mental comorbidity.

In addition, three categories were created to assess users’ work functioning (i.e., the extent to which their symptoms are impacting their work). The three categories are: (1) no work functioning issues reported, (2) presenteeism and (3) absenteeism. The assessment of these categories is based upon the following work-related questions that are derived from the iMTA Productivity Cost Questionnaire (iPCQ)54 and supplementary questions on the number of times of absence from work in the last year: Are you currently on sick leave?; During the last 4 weeks have there been days in which you worked but during this time were bothered by any kind of problems that made it difficult for you to get as much work finished as you normally do?; Have you missed work more than 3 times in the last year as a result of being sick?; Are you currently on sick leave since more than 6 weeks?

Users will be classified into 42 different profiles based on the assessment. The EMPOWER intervention is designed to guide users to use different modules according to their specific profile.

Module to promote wellbeing and mental health

This intervention level is directed toward employees following an individual approach and designed based on strategies and techniques of the CBT model.55,56 It presents several sections of psychoeducational and practical content (e.g., relaxation exercises and breathing techniques), allows for tracking of daily-life moods, promotes healthy sleeping habits and encourages the development of personal attitudes and skills (e.g., cognitive restructuring techniques).

The psychoeducation material aims to enhance mental health literacy, attitudes and supportive behaviours with regard to wellbeing and mental health and includes information on core constructs of the intervention (i.e., stress, depression, anxiety and insomnia). The content includes a non-expert definition of each construct, information regarding signs, symptoms, potential causes and practical strategies. A didactic approach and user-friendly format has been employed to present these materials.

Work functioning module

This intervention level is for participants who may be experiencing lower productivity or sickness absences due to their symptoms and was designed to last for 7 weeks.57,58 It incorporates tools, psychoeducation, and CBT goal setting presented to employees according to the assessment of their mental and physical health when they begin using the app. It also encourages employees to seek guidance and help from health professionals when needed and is designed to complement the treatment provided by a health professional. Each module was designed to target the most common health symptoms that impact work functioning, such as anxiety, depression or physical health conditions and common comorbidity of these symptoms.

Translation and cultural adaptation

Differences between workplace cultures, expectations for employees and differences in perspectives on mental health are expected. Thus, cultural appropriateness and institutional context were considered for each of the four cultural settings (Finland, Poland, UK and Spain). The translation and cultural adaptation procedure followed a ‘cultural sensitivity approach’59 involving three steps: (1) translation and changes to vocabulary and grammar to make content more understandable for the participants from that setting; (2) evaluation by potential end users and experts through focus groups or functional alternatives (e.g., interviews and written consultations); and (3) modification of the material based on the end users’ feedback. Two additional steps were added, based on a ‘negotiated consensus approach’.60 One step was added between steps 1 and 2, which was a discussion between the research teams on particularly challenging concepts. The other step was ongoing documentation on modifications and reasons for these modifications.61

Study design

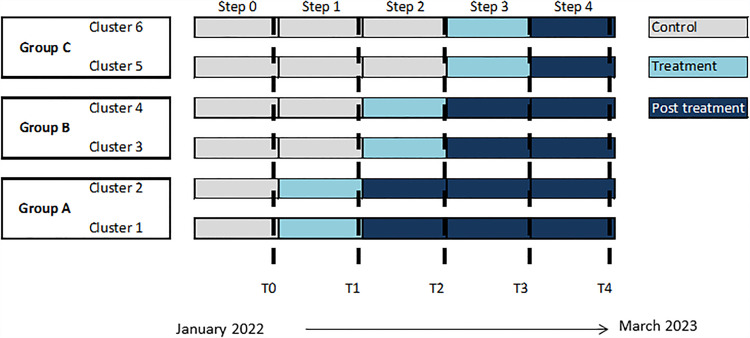

We will conduct a stepped-wedge trial design (SWTD), a repeated-measure design in which the sample is randomly divided into several subsamples which are observed at all-time points but differ with respect to the moment at which the experimental intervention is implemented. If measurement occurs on T different occasions, T-1 subsamples are created. In an SWTD, the experimental treatment is rolled out sequentially to the clusters over a number of time periods (Figure 1).62 By the end of the period, all clusters will have implemented the intervention. The data are collected at fixed intervals.

Figure 1.

The stepped-wedge trial design for the EMPOWER intervention.

The SWTD has several advantages: (a) individuals in the trial act as their own controls, (b) because of the sequential design they can be easily controlled for a time effect and (c) since every individual is in the control group as well as in the experimental group, it reduces randomization biases. This design was selected in order to retain the power of randomization while offering all companies enrolled in the trial the desirable intervention.63,64 To further strengthen the study, we will perform a qualitative evaluation within the RCT.

The formal trial period will run from January 2022 and last to March 2023. The intervention will be delivered in four steps to companies from four countries (i.e., Finland, Poland, UK and Spain), as shown in Figure 1. In each country, clusters (i.e., companies or departments) will randomly be assigned to A, B and C groups. These groups differ in the time when participants have access to the intervention part of the app. Recruitment of individuals and baseline data collection will occur in T0. Thus, participants from the three groups (A, B and C) will be invited to download the app at the same time, that is, at the beginning of the RCT. Data will be collected at the individual level within the clusters at five-time points: baseline (T0) and at the end of the four steps (T1 to T4, see Figure 1). The assessment protocol will be delivered through the app with no time limit to complete it. All participants will complete the baseline assessment at T0, but only participants in those clusters in group A will start the intervention immediately after T0. After 7 weeks of using the app and having access to the website (i.e., with material related to the anti-stigma campaign and recommendations for employees to deal with psychosocial risk factors), they will answer a post-treatment assessment protocol through the app. At the same time, clusters within groups B and C, which serve as control groups, will also complete the assessment at T1. Clusters in group B will start the intervention in step 2, after completing the second assessment, and clusters in group C in step 3. All clusters will answer a total of five assessments.

Setting and participants

We will recruit employees from SMEs and public agencies from Finland, Poland, UK and Spain. According to the European Commission, SMEs are organizations with fewer than 250 employees and an annual turnover not exceeding EUR 50 million, and/or an annual balance sheet total not exceeding EUR 43 million.65 These criteria are applied in the four study countries. Public agencies are organizations with a public legal personality dependent on the administration for the performance of activities within the competence of the region or country under a functional decentralization regime. Public agencies are classified into the following types: administrative agencies, public business agencies and special regime agencies. Large companies (i.e., ≥250 employees) can also participate in the control trial despite not being the main focus of the RCT. This allows for separate analyses to determine if the EMPOWER intervention is effective in this type of company.

There will be no restriction based on the size of the participating organization or the economic sector to which they belong.

Sample size calculation

As the results of previous studies vary significantly regarding the effectiveness of programs to improve mental health in the workplace, a conservative approach that allows the detection of small changes and effect sizes was used. This approach is based on a review on the impact of mental health programs on presenteeism in the workplace.66 This calculation also considers loss to early and late follow-ups (25%). Given these considerations, along with an expected effect size of d = 0.30, a type I error of 0.05 (bilateral test) and a power of 80%, a sample of 729 participants in total will be needed. However, taking into account that multilevel analyses will be carried out because of cluster randomization, this sample size must be corrected by 1.2,67 resulting in a final sample of 874 participants.

Participant eligibility criteria

All the employees from each company or department will be invited to participate in the SWTD. The inclusion criteria for participants are: (1) being aged 18 years or older; (2) having a mobile phone with Internet access; (3) having sufficient knowledge of the local language; and (4) giving informed consent. Once these criteria are met, participants will be invited to download the application and use the app.

The informed consent process will be integrated within the app. Once accepted, participants will receive the assessment protocol in which they will be asked to report on depressive and anxiety symptoms using the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales. Participants who reach the threshold to consider the presence of severe depression and anxiety (PHQ > 19 and/or GAD > 15) will be advised to seek specialized care and provided with adequate information on the availability of treatment but will be included in the RCT. They will additionally be informed that the use of the app does not constitute or replace specialized medical treatment and provided with the contact details of the local research team (telephone number and e-mail address).

Special case: people with suicidal thoughts

Item 9 of the PHQ-9 questionnaire assesses the presence of suicidal thoughts (“Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way”). The presence of this condition is considered serious. Therefore, it will be explicitly stated in the participant information sheet that EMPOWER intervention is specially designed to prevent mild mental health problems and to promote wellbeing in the workplace but not designed to treat more severe mental health problems, including suicidal ideation. In the event of a participant suffering from more severe mental conditions, it will be strongly recommended for them to visit their physician or other health professional, who will evaluate their condition and provide appropriate treatment. These participants will be also informed that the app does not replace medical treatment or psychotherapy. Additionally, if a participant reports suicidal ideation with item 9 of the PHQ-9 questionnaire during the evaluation and immediately before using the EMPOWER app, they will again receive a similar message through the app along with options for local resources they can refer to (e.g., helplines). These participants will also be asked if they wish to continue using the app.

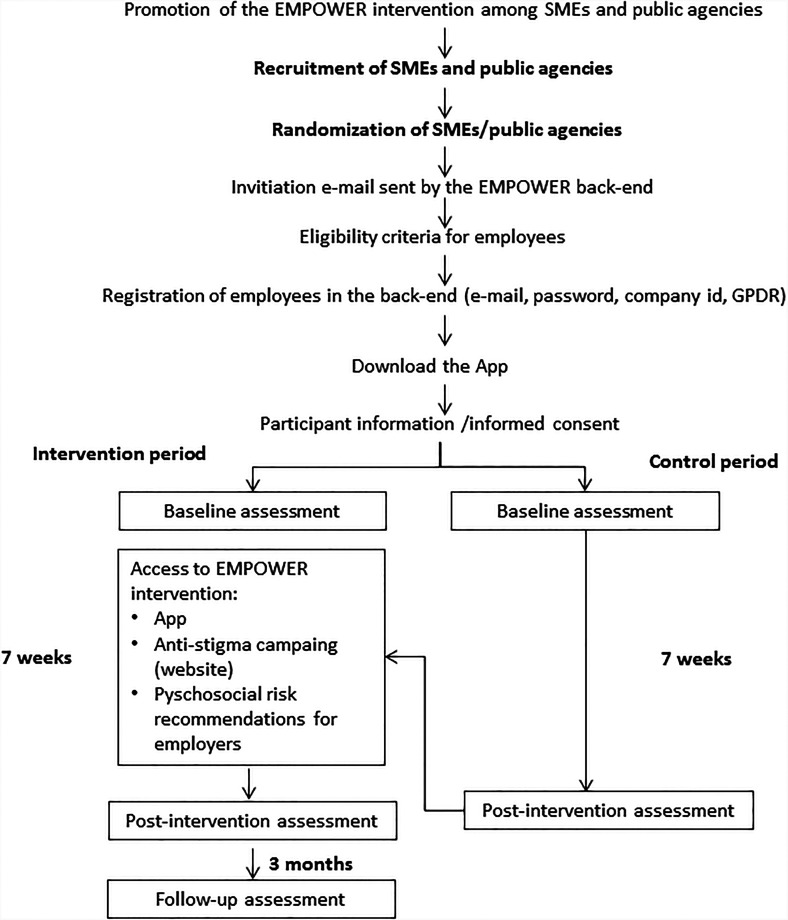

Recruitment and inclusion of companies and participants

Figure 2 shows the recruitment of companies and the inclusion and randomization of participants in the control trial. After signing the agreement between the EMPOWER consortium and the employer, the company's contact person (e.g., human resources' manager, director or chief executive officer) will be invited to confirm the organization's participation in the back-end environment of the project. Employers will send email invitations to employees via the EMPOWER email address. Participation will be voluntary and the email addresses used by the employer to generate employee email invitations will be automatically deleted after sending, thus they will not be accessed by EMPOWER. These email invitations will request the employee's participation in the RCT and include a unique and untransferable link to download the app and a company code to access the app.

Figure 2.

Flow of participants in the control trial.

Employees will be then asked to provide an email address, their company code and a password. Once registered, they will be asked to accept the privacy and cookie terms, in accordance with the general data protection regulation (GDPR).68 Afterward, participants will receive an email to confirm their registration and activate their account.

To access more content in the app, employees will be asked to give their informed consent. Employees will receive information about the study, the use of their data by EMPOWER and their rights under the GDPR and local national laws (i.e., in Finland, Poland, Spain and UK). The informed consent process will consist of two steps: first, workers will give their consent based on the information provided (‘I agree’/‘I disagree’). Second, they will receive a message for re-confirmation. It is important to note that study data will only be collected from participants once they have provided consent.

After obtaining informed consent, employees will be asked to complete several questionnaires and will then be guided through different modules and content sections of the EMPOWER app. The recruitment of employees will start in January 2022.

Randomization

In this study, clusters are companies or subparts of companies (if the companies are large) and nested within countries. Blockwise randomisation will be performed within clusters of companies, selected from one country. When possible, randomization will take into account strata according to the size of the company or department, type of workers (blue or white collar) and type of organization (SME or public agency). An independent statistician will randomise each block in one of the three groups (A, B or C) by an automated computer program.

Ethical approval

The trial is registered at the ClinicalTrial.gov with trial ID NCT04907604. The protocol is documented in accordance with the CONSORT extension guidelines for reporting SWTD (Supplementary Table 1).69 The study protocols have been approved by the ethics committees of Fundació Sant Joan de Déu (PIC-39-20), Turku University Hospital (PIC-993966082), University of York (HSRGC250321) and Institute of Occupational Medicine, University of Lodz (9/2020).

Assessment protocol

Once employees agree to participate and provide informed consent, and before having access to the EMPOWER platform, they will be asked to answer an assessment protocol delivered through the app. The assessment protocol will be delivered at five-time points that correspond to the five steps of the SWTD. All clusters will have a baseline assessment (prior to the intervention), another one immediately after the intervention (7 weeks) and after 3 months of follow-up.

Table 1 shows the different instruments and variables that will be measured at the five-time points. The assessment protocol will include the following demographic variables: date of birth, highest educational level achieved, current marital status, current occupation and other work-related variables (duration of workday, days worked per week, type of contract and work schedule). Mental health will include depressive symptomatology, assessed with the PHQ-9,51 anxiety symptoms, measured with the GAD-7,50 perceived stress levels (using the perceived stress scale, PSS-4)70 and severity of insomnia, measured with one item from the Insomnia severity index.71 Levels of physical activity in the last 7 days will be measured with a short version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ).72 The WHO-573 will be used to determine levels of wellbeing. The presence of physical symptoms will be assessed through the PHQ-15 somatic scale.52 Self-reported chronic conditions diagnosed by a medical professional in the last 12 months include asthma, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; serious cardiac condition or heart attack, stroke, high blood pressure; gastric ulcer, serious bowel/intestinal disorder (e.g., Crohn's disease), gall stones or gallbladder illness; liver disease; kidney stones, serious renal disease; chronic urinary tract infection; diabetes; thyroid disease; disc prolapse, arthrosis or rheumatoid arthritis; epilepsy, Parkinson, multiple sclerosis; migraine; cancer.53

Table 1.

Assessment measures.

| Baseline (Step 0) | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | X | Xa | Xa | Xa | Xa |

| PHQ-9 | X | X | X | X | X |

| GAD-7 | X | X | X | X | X |

| PSS-4 | X | X | X | X | X |

| Insomnia severity index | X | X | X | X | X |

| WHO-5 | X | X | X | X | X |

| IPAQ short version | X | X | X | X | X |

| EQ-5D-5L (and visual analog scale) | X | X | X | X | X |

| PHQ-15 somatic scale | X | X | X | X | X |

| Chronic conditions in the last 12-months | X | Xb | Xb | Xb | Xb |

| IPCQ | X | X | X | X | X |

| iMCQ | X | X | X | X | X |

| Absenteeism | X | X | X | X | X |

| MHQoL | X | X | X | X | X |

Only questions about work-related variables will be asked at T1, T2, T3 and T4.

A skip question will be asked (Did you develop a new chronic condition?).

To determine the cost-effectiveness of the EMPOWER intervention, the five-level EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L),74 the Mental Health Quality of Life questionnaire (MHQoL),75 the iPCQ,54 and the iMTA Medical Consumption Questionnaire (iMCQ)76 will be administered. The EQ-5D-5L is a preference-based instrument that has been developed to evaluate health-related quality of life in five domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, panic/discomfort and anxiety and depression). The MHQoL is a quality of life instrument that assesses and values mental health-related quality of life in seven dimensions (self-image, independence, mood, relationships, daily activities, physical health and hope). Absence from work and presenteeism will be measured using the iPCQ. Productivity costs due to absenteeism and presenteeism will be calculated based on the country-specific average labour costs. To identify respondents with high levels of absence from work (being off sick in the last year at least 3 times or more) will be asked with questions created ad hoc for this study. Finally, the iMCQ will be used to collect data on health care utilization. In order to estimate medical costs, the utilization of services will be multiplied by corresponding country-specific reference prices. Data related to the use of the app will be gathered, including time spent in-app, frequency of use and number of log-ins. This will be used to evaluate the feasibility/user-friendliness of the app.

In order to reduce the burden for participants in answering a long questionnaire, some measures are implemented. First, the questionnaires are embedded within the app and presented as different topics or sub-headings (e.g., demographics, depression, anxiety and so on). The app shows, for each topic, the level of completion (i.e., 60% completed). Participants can continue answering the questionnaires in another moment with no time limit, and reminders are sent periodically via email after the third day of not completing the assessment protocol.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome is a reduction of presenteeism. Presenteeism has been defined as the time spent at work with decreased levels of productivity due to mental or physical health issues.4 In this study, it will be measured with the iPCQ, a questionnaire that includes three questions to identify health-related diminished productivity at work.54 Employees will be asked if they suffer from health problems at work, for how many days and to rate their work performance on these days in comparison to their functioning on normal working days with a 10-point rating scale. The answer to these questions will be combined, with higher scores indicating higher presenteeism. Secondary outcomes include improvement in depressive symptomatology for employees, measured with the PHQ-9 sum score; improvement in anxiety symptoms (by means of the GAD-7 total scores), at both 7 weeks and 3-month follow-up; improvement of perceived stress (measured with the PSS-4 scale) and in wellbeing (assessed with the WHO-5 scale), reduction of insomnia severity (insomnia severity scale), PHQ-9 and absenteeism, measured with the iPCQ.

Statistical analysis

Effectiveness analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used to summarize the characteristics of employees and companies. We will analyze participants according to their randomized assignment (intention to treat) to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention on primary and secondary outcomes. Participants will be analyzed in one of the three groups their cluster was assigned to at each time point (i.e., groups A, B and C). To evaluate whether the intervention is effective in reducing levels of presenteeism (primary outcome) compared with usual care periods, we will calculate linear mixed effects models. Secondary analyses will include linear mixed models (for continuous secondary outcomes, e.g., PHQ-9 or GAD-7 scores), and generalized mixed effects models for binary secondary outcomes (e.g., presence of absenteeism). Models will include intervention status and time as fixed effects, and clusters (i.e., companies or departments), countries (Finland, Poland, UK and Spain) and individuals as random effects. All models will be adjusted for gender, age and level of education. When appropriate, organizational or individual factors strongly correlating with the outcome will also be included in the models as fixed effects. In order to see whether there are significant differences between men and women in terms of effectiveness, the analyses will also be conducted stratified by gender. Additionally, we will conduct separate analyses to see whether the effectiveness of the intervention differs according to different types of companies (e.g., SMEs versus public agencies, different sizes, including large companies, if available, type of economic activity).

The estimated effect of the intervention will be reported as the mean outcome difference for continuous outcomes and odds ratio (OR) for binary outcomes between intervention and control periods, assuming a constant treatment effect over time. To determine the number of people who achieve a positive and reliable result, the reliable change index (RCI) will be used. The RCI is used to evaluate whether a change over time in an individual score (the difference between pre- and post-treatment) is statistically significant. The numerator represents the actual observed difference score between the pre- and post-treatment and the denominator represents the standard error of measurement of the difference.

Estimated effects will be reported with their 95% confidence intervals and p values <0.5 will be considered as statistical significance. The statistical analysis will be conducted with program R.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

In a cost-effectiveness analysis, the differential costs (incremental costs) are set off against the differential effects (incremental effects) of the comparator to assess whether the intervention is value for money.77 The current economic evaluation considers the incremental costs and effects associated with the EMPOWER intervention and the group who has no access to it (comparator). Two analytic techniques will be applied. In line with one of the goals of the EMPOWER intervention, the primary outcome measure is to reduce presenteeism and reduce time to return to work/absence from work. Thus, a cost-benefit analysis (CBA) will be conducted, assessing the costs compared to the benefits expressed in costs of productivity loss due to the absence of work and presenteeism. In addition, a cost-utility analysis (CUA) will be conducted. A CUA is a frequently applied type of economic evaluation in which health benefits are expressed as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). The QALY combines length of life (i.e., the number of remaining years a person is expected to live) and health-related quality of life experienced during those years, and will be calculated with the EQ-5D-5L. In case of availability of a country-specific value set, this will be used (Spain, Finland and UK). In absence of a national value (e.g., Poland) set a proxy value set is applied, based on the supra-national value sets for homogenous country clusters in Europe established in the PECUNIA-project (https://www.pecunia-project.eu). The CBA and CUA will be conducted from a societal perspective as well as from the employers’ and employee's perfective types of costs that will be included in the three perspectives and sources of unit costs per country (see Tables 2 and 3, respectively). The intervention costs will include the costs of development, providing, maintenance, technical support and VAT. The costs per user will be presented for different levels of use, e.g., dividing the costs by the actual number of users, potential users and expected users. The unit costs for valuation of the items of the iMCQ and iPCQ will be country-specific.

Table 2.

Perspective cost-effectiveness analyses and costs included.

| Perspective | Costs included |

|---|---|

| Societal | Intervention costs |

| Productivity costs (absence from work and presenteeism) | |

| Health care utilization (e.g., general practitioner, mental health services, medication physiotherapy) | |

| Informal care | |

| Employer | Intervention costs |

| Productivity costs (absence from work and presenteeism) | |

| Employee | Time |

| Informal care |

Table 3.

Source for unit cost per country.

| Country | Unit cost source |

|---|---|

| UK | Jones, Karen C., Burns, Amanda (2021) Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2021. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care. Personal Social Services Research Unit, Kent, UK, 185 pp. ISBN 978-1-911353-14-0. (doi:10.22024/UniKent/01.02.92342) |

| Spain | Literature and experts |

| Poland | Literature and experts |

| Finland | Literature and experts |

Generalized linear models will be calculated, adjusted for any relevant covariates and baseline values for costs and QALYs.78 The total QALYs from the regression models will be used to estimate the area under the curve (AUC). The modelled estimates from the regression model, i.e., estimated mean difference in total cumulative costs between arms and estimated mean difference in total QALY between arms, will be used to estimate the incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER). These estimates will be bootstrapped to assess the uncertainty surrounding the ICER. The ICER will be calculated by dividing the difference in total costs (incremental cost) by the difference in QALYs (incremental effect). We will apply the county-specific costs-effectiveness (cost per QALY) threshold, e.g., the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) currently uses a cost-effectiveness threshold in the range of £20,000 to £30,000 per QALY for reimbursing new drugs in the NHS.79 In absence of an official cost-effectiveness threshold we will present the cost-effectiveness for different levels of willingness to pay. Moreover, we will present cost-effectiveness acceptability curves to summarize the uncertainty in estimates of cost-effectiveness.

Quality assurance, data safety and incidental findings

Quality control procedures will be implemented during the fieldwork, cleaning data and analysis. Each local team and the project coordinator's team (Fundació Sant Joan de Déu, FSJD) will be responsible for checking completeness, consistency and quality. Personal data and data collected in the five assessment points will be hosted in a secure server at the Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu hospital. This server complies with the European standards in security, ethics and integrity. Personal data will be removed from the datasets and kept separately. Data will be pseudonymized and will only be linked to the user by a unique private identifier. This identifier is internal to the system and will not be visible to any user, neither the final user nor any user with permissions to query response results. Only the coordinating team will have access to personal data.

Databases used for analysis purposes will not contain personal data, and only members of the consortium will have access to them. Consortium members should submit an application for pseudonymized data access which will be evaluated by an internal board, who will decide whether access is granted or not, or if additional information is needed. Upon approval of the proposal, a data use agreement and a data use protection plan must be submitted and signed by the applicant as well as the coordinator. In case of the involvement of researchers foreign to the consortium, a supplemental agreement for research staff must be signed.

Considering that we will not use any of the main analytical techniques usually associated with a higher probability of appearance of incidental findings (i.e., large-scale genetic sequencing, testing of biological specimens or neuroimaging), the probability of incidental findings appearance during the RCT is expected to be low. Nevertheless, people with elevated levels of anxiety and depression (i.e., PHQ> 19 and/or GAD> 15 scores) might constitute anticipable incidental findings, especially for participants who are not aware of suffering from these conditions. For those participants falling into these categories (i.e., high depression and anxiety) or having suicidal thoughts, they will be informed through the app with a message about the presence of these conditions and recommended to visit a physician/health professional. They will be reminded that the app is not designed for treating severe mental conditions, and they will also be provided with national/local resources. Additionally, if they are receiving treatment for their mental condition, they will be advised to discuss the convenience of using the app with their clinician. Finally, participants will be provided with the contact details of the local research team with a telephone number and an e-mail address in case they wish to discuss the results of their elevated anxiety, depression and/or suicidality levels.

Qualitative evaluation

A qualitative assessment will be conducted during the RCT to understand the working mechanisms of the EMPOWER platform and collect user insights that are relevant for the implementation of the platform after the study. The qualitative assessment will be conducted according to the realist evaluation approach,80 a methodology used to establish an in-depth understanding of ‘what works, for whom, and in what settings’. It thereby facilitates the identification of factors by which the intervention is adopted or rejected, enabling an understanding of how and why the implementation succeeds or fails. Data will be collected through interviews with employees and employers (including managers and HR consultants) that participate in the trial.

Participants and sampling

The qualitative assessment will be carried out with a sample of 15 employees and 5 employers per country (Finland, Poland and Spain) from group B (Figure 1). They will be interviewed at T1 (time at which they can start using the intervention) and T2 (end of the intervention). Sampling for realist interviews will be theory-based, that is, respondents will be selected according to their position to cast light on the research questions that are central to the evaluation. As the experiences with the EMPOWER platform might work differently for particular sub-groups or circumstances, the selection of participants will consider several characteristics: type and size of an organization, type of employee (blue/white collar), age and gender of the respondent.

Data collection and analysis

One-on-one, semi-structured online interviews will be conducted, with questions guided by the principles of realist evaluation. Topics include participants’ experiences using the EMPOWER platform, including the barriers and facilitators of its effective use. The estimated time per interview is 30–45 min. The interviews will be executed in the native language of the interviewee by one of the local researchers with previous training in the administration of the interview. All interviews will be audio-taped and fully transcribed before coding and analysis in ATLAS.ti software.

Quality assurance and ethics

This study protocol for qualitative assessment was approved by the Ethics Research Committee (CEIm) of Fundació Sant Joan de Déu (PIC-03-22). Before participating in the interviews, all participants will give their informed consent. Employees, as part of the RCT, are asked to provide their consent and personal contact details to participate in the qualitative interviews. The coordination team, as data controller, will access this information and will choose a certain number of people to participate per country, who will be assigned a code different from the code used for the RCT. Therefore, and except in the assumption that the number of participants in the RCT is very low and similar to the number of participants in the interviews, the risk of linking the responses to the interviews with the data from the RCT is expected to be low. In the process of selecting potential participants for the qualitative interviews, the coordination team will select the appropriate ratio of the number of interviews versus the number of participants per company. In this selection, and if necessary, it will be avoided to choose participants who, due to gender or other sociodemographic characteristics, could lead to the possible identification of the person or to the relationship with the RCT data.

Discussion

Interventions delivered by digital means to improve wellbeing and mental health and reduce presenteeism and absenteeism in the workplace represent a promising approach, especially for SMEs and public agencies, where there is a lack of resources for these types of programs.21 In this context, the EMPOWER project is aimed to develop and evaluate a culturally adapted, multi-modal program that includes an eHealth application to address the increasing burden of mental health problems in the workplace. By using an SWTD, we will evaluate whether the EMPOWER intervention (consisting of a website and an app addressed to employees) is effective and cost-effective to improve mental health and wellbeing, as well as productivity in the companies.

By minimally relying on professionals for implementation, the intervention is expected to be easily accessible to SMEs and other types of institutions (e.g., public sector agencies) and will not impose a substantial financial burden. Additionally, self-guided e-mental interventions have shown efficacy for common mental disorders when compared with control conditions, although the effects seem smaller compared with guided interventions including a psychotherapist.81 Finally, by focusing on the individual and relying on using online tools, the highest standards of confidentiality can be achieved.

The combination of a three-tiered intervention structure (universal, secondary and tertiary prevention) within an integrating intervention is expected to effectively prevent mental health problems in the workplace. Additionally, the EMPOWER intervention addresses mental and physical comorbidity, which is a novel aspect of the intervention. Finally, one goal of the EMPOWER intervention is for it to be useful and effective throughout the EU. This requires not just translation of the material, but also careful consideration of cultural adaptation that may be necessary for the digital platform's efficacy. The intervention was carefully adapted to ensure the usability, acceptability and adherence for each setting as well as the comparability of the material across the four settings.

The online design of the EMPOWER intervention enables delivering it to a wide population, reduces costs, and ensures high standards of confidentiality and security. If the EMPOWER platform proves to be effective and cost-effective in SMEs and public agencies, future scale-up of its implementation in other settings, such as large companies, is expected to result in large-scale cost reduction in the labour market.

However, some limitations are expected in this study. First, there are implicit barriers associated with participation in scientific studies. For example, the SWTD implies that there are some companies that will start using the platform after a considerable time span. Employees will also be asked to answer several questionnaires at different time points and some will be asked to do so without access to the content of the intervention, which might result in high drop-outs and missing data. We used a conservative attrition rate to calculate the sample size needed in each country. Additionally, statistical methods will take into account missing at random data to mitigate this limitation. Related to this, online interventions are expected to have high attrition rates.82 To maintain engagement and reduce attrition, the app will automatically send pop-up reminders to users to answer the questionnaires, to inform them about when the content of the app and the website is available to use, and the level of completion of the questionnaires. Additionally, during the SWTD, we will engage managers to help us increase participation and reduce attrition of employees. Second, the voluntary nature of the study might result in a sample that does not necessarily correspond to the whole working population. However, this is an inherent aspect of this type of studies, and by means of qualitative data, we will have valuable, real data to analyze the facilitators and barriers of the implementation. The qualitative analyses will also focus on differences between settings, countries, gender, etc. Related to this, and considering that the effectiveness and usability of this type of e-health interventions might differ across countries and settings, future studies will be needed to investigate the implementation in other European countries. Finally, the use of eHealth platforms and apps might also face potential technological issues, such as lack or reduced Internet access, or constant adaptations to system updates (i.e., iOS and Android).

Despite these limitations, if the EMPOWER intervention demonstrates to be effective and cost-effective for reducing presenteeism, absenteeism and preventing common mental health problems in the workplace, this could be translated into employees with better mental health and wellbeing, and a healthier lifestyle. In the end, this could also significantly reduce costs related to absenteeism and presenteeism, and decrease employees’ time to return to work. Finally, the implementation of a multi-modal, online cost-effective intervention at work could also positively impact society by reducing human suffering, social exclusion, stigmatization of the mentally ill and their families and diminishing economic costs. This impact will be assessed during the course of the project with the evaluation of the program.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076221131145 for Study protocol of EMPOWER: A cluster randomized trial of a multimodal eHealth intervention for promoting mental health in the workplace following a stepped wedge trial design by Beatriz Olaya, Christina M. Van der Feltz-Cornelis and Leona Hakkaart-van Roijen, Dorota Merecz-Kot, Marjo Sinokki, Päivi Naumanen, Jessie Shepherd, Frédérique van Krugten, Marleen de Mul, Kaja Staszewska, Ellen Vorstenbosch, Carlota de Miquel, Rodrigo Antunes Lima, José Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Luis Salvador-Carulla, Oriol Borrega, Carla Sabariego, Renaldo M. Bernard, Christophe Vanroelen, Jessie Gevaert, Karen Van Aerden, Alberto Raggi, Francesco Seghezzi, Josep Maria Haro in Digital Health

Footnotes

Authors’ note: The EMPOWER Consortium includes (in alphabetic order): Andysz A15; Ayuso-Mateos JL2,8; Bernard RM11; Borrega O10; Brach M11; Cabello M8; Cabré J10; Cacciatore M13; Chen T9; Cristóbal P1,2; de Miquel C1,2; de Mul M5; Félez M1,2; Gevaert J12; González L10; Gutiérrez D1,2; Hakkaart-van Roijen L5; Haro JM1,2; Klimczak E15; Leonardi M13; Lima RA1,2; López-Carrión M10; Lukersmith S9; Mauro A14; Merezc-Kot D6; Miret M8; Naumanen P7; Olaya B1,2; Ortiz-Tello A8; Peeters S5; Porcheddu D14; Raggi A13; Rodríguez-McGreevy K8; Sabariego C11; Salvador-Carulla L9; Seghezzi F14; Shepherd J3; Sinokki M7; Smith N3; Staszewska K15; Tiraboschi M14; Toppo C13; van Aerden K12; Van der Feltz-Cornelis CM3,4; van Krugten F5; Vanroelen C12; Vorstenbosch E1,2

1Research, Innovation and Teaching Unit, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu, Sant Boi de Llobregat, Spain

2Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain

3MHARG, Department of Health Sciences, Hull York Medical School, University of York, York, United Kingdom

4Institute of Health Informatics, University College London, London, UK

5Erasmus School of Health Policy and Management (ESHPM), Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

6Institute of Psychology, University of Lodz, Lodz, Poland

7Turku Centre for Occupational Health, University of Turku, Turku, Finland

8Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

9Centre for Mental Health Research, Research School of Population Health, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia

10Òmada Interactiva, SLL, Barcelona, Spain

11Swiss Paraplegic Research (SPF), Nottwil, Switzerland

12Interface Demography, Department of Sociology, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

13Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, UO Neurologia Salute Pubblica e Disabilità. Milano, Italy

14Fondazione ADAPT, Milano, Italy

15Nofer Institute of Occupational Medicine, Lodz, Poland

Contributorship: BO, CVDF-C, LH, DM-K, MS, JLA-M, LS-C, CS, CV, AR, FS and JMH conceived the study and are principal investigators. All other authors contributed to writing the protocol and revising the article.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. CFC declares honoraries received for lectures from Lloyds Register Foundation and Janssen UK and holds grants from the British Medical Association, NIHR, and the European Union Horizon Program.

Ethical approval: The study protocols have been approved by the ethics committees of Fundació Sant Joan de Déu (PIC-39-20), Turku University Hospital (PIC-993966082), University of York (HSRGC250321) and Institute of Occupational Medicine, University of Lodz (9/2020).

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP1195937) and the European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme Health (grant number APP1195937, 848180). BO is supported by the Miguel Servet (CP20/00040) contract, funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spain) and co-funded by the European Union (ERDF/ESF, “Investing in your future”). C.M. has received funding in form of a pre-doctoral grant from the Generalitat de Catalunya (PIF-Salut grant, code SLT017/20/000138).

Guarantor: BO

ORCID iDs: Beatriz Olaya https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2046-3929

Leona Hakkaart-van Roijen https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0635-7388

Carlota de Miquel https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3602-4146

Rodrigo Antunes Lima https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7778-2616

Renaldo M. Bernard https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6958-3369

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Health and Safety Executive. Health and safety at work. Summary statistics for Great Britain 2020, https://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/overall/hssh1920.pdf (2020).

- 2.World Federation of Mental Health. Mental Health in the workplace, https://wfmh.global/wp-content/uploads/2017-wmhd-report-english.pdf (2017).

- 3.Matrix Insight. Economic analysis of workplace mental health promotion and mental disorder prevention programmes and of their potential contribution to EU health, social and economic policy objectives, https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/default/files/mental_health/docs/matrix_economic_analysis_mh_promotion_en.pdf (2013).

- 4.Kigozi J, Jowett S, Lewis M, et al. The estimation and inclusion of presenteeism costs in applied economic evaluation: a systematic review. Value Health 2017; 20: 496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olesen J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, et al. The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur J Neurol 2012; 19: 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.EU-OSHA. Calculating the cost of work-related stress and psychosocial risks, https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/calculating-cost-work-related-stress-and-psychosocial-risks (2014, accessed 22 May 2022).

- 7.EU Compass. Good practices in mental health and well-being. Mental health at work, in schools, prevention of depression and suicide, https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/default/files/mental_health/docs/2017_mh_work_schools_en.pdf (2017).

- 8.Phillips EA, Gordeev VS, Schreyögg J. Effectiveness of occupational e-mental health interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scand J Work Environ Health 2019; 45: 560–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogg B, Medina JC, Gardoki-Souto I, et al. Workplace interventions to reduce depression and anxiety in small and medium-sized enterprises: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2021; 290: 378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarro L, Llauradó E, Ulldemolins G, et al. Effectiveness of workplace interventions for improving absenteeism, productivity, and work ability of employees: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17(6): 1901. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph17061901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hesketh R, Strang L, Pollitt A, et al. What do we know about the effectiveness of workplace mental health interventions? London: The Policy Institute, Kings' College London, April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schultz AB, Chen CY, Edington DW. The cost and impact of health conditions on presenteeism to employers: a review of the literature. PharmacoEconomics 2009; 27: 365–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva-Costa A, Ferreira PCS, Griep RH, et al. Association between presenteeism, psychosocial aspects of work and common mental disorders among nursing personnel. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 1–E12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cancelliere C, Cassidy JD, Ammendolia C, et al. Are workplace health promotion programs effective at improving presenteeism in workers? A systematic review and best evidence synthesis of the literature. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 395. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stratton E, Jones N, Peters SE, et al. Digital mHealth interventions for employees: systematic review and meta-analysis of their effects on workplace outcomes. J Occup Environ Med 2021; 63: e512–e525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paganin G, Simbula S. Smartphone-based interventions for employees’ well-being promotion: a systematic review. Electron J Appl Stat Anal 2020; 13: 682–712. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDaid D, Park A La. Counting all the costs: the economic impact of comorbidity. Key Issues in Mental Health 2015; 179: 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu Z, Burger H, Arjadi R, et al. Effectiveness of digital psychological interventions for mental health problems in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7: 851–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howarth A, Quesada J, Silva J, et al. The impact of digital health interventions on health-related outcomes in the workplace: a systematic review. Digit Heal 2018; 4: 205520761877086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borghouts J, Eikey E, Mark G, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of user engagement with digital mental health interventions: Systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23(3): e24387. DOI: 10.2196/24387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deloitte. Rewriting the rules for the digital age. 2017 Deloitte global human capital trends, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/central-europe/ce-global-human-capital-trends.pdf (2017).

- 22.Carolan S, Harris PR, Cavanagh K. Improving employee well-being and effectiveness: systematic review and meta-analysis of web-based psychological interventions delivered in the workplace. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19(7): e271. DOI: 10.2196/JMIR.7583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner SL, Koehn C, White MI, et al. Mental health interventions in the workplace and work outcomes: a best-evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Int J Occup Environ Med 2016; 7: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Søvold LE, Naslund JA, Kousoulis AA, et al. Prioritizing the mental health and well-being of healthcare workers: an urgent global public health priority. Front Public Heal 2021; 9: 679397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.OECD. Policy recommendations for SME recovery and long-term resilience, https://biac.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Business-at-OECD-policy-paper-for-SME-recovery-and-longer-term-resilience-1.pdf (2021).

- 26.Benning FE, van Oostrom SH, van Nassau F, et al. The implementation of preventive health measures in small- and medium-sized enterprises-A combined quantitative/qualitative study of its determinants from the perspective of enterprise representatives. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19(7): 3904. DOI: 10.3390/IJERPH19073904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saito J, Odawara M, Takahashi H, et al. Barriers and facilitative factors in the implementation of workplace health promotion activities in small and medium-sized enterprises: a qualitative study. Implement Sci Commun 2022; 3: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rimmer A. Lack of mental health support in the public sector. Br Med J 2017; 357: j2731. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laaksonen E, Martikainen P, Lahelma E, et al. Socioeconomic circumstances and common mental disorders among Finnish and British public sector employees: evidence from the Helsinki health study and the Whitehall II study. Int J Epidemiol 2007; 36: 776–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Björkenstam E, Helgesson M, Gustafsson K, et al. Sickness absence due to common mental disorders in young employees in Sweden: are there differences in occupational class and employment sector? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2021; 57: 1097–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deloitte. Mental health and employers: The case for investment, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/public-sector/deloitte-uk-mental-health-employers-monitor-deloitte-oct-2017.pdf (2017).

- 32.do Monte PA. Public versus private sector: do workers’ behave differently? EconomiA 2017; 18: 229–243. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Homrich PHP, Dantas-Filho FF, Martins LL, et al. Presenteeism among health care workers: literature review. Rev Bras Med do Trab 2020; 18: 97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mastekaasa A. Absenteeism in the public and the private sector: does the public sector attract high absence employees? J Public Adm Res Theory 2020; 30: 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gritzka S, Macintyre TE, Dörfel D, et al. The effects of workplace nature-based interventions on the mental health and well-being of employees: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry 2020; 11: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernard R, Toppo C, Raggi A, et al. Strategies for implementing occupational eMental health interventions: a scoping review. J Med Internet Res, 2022; 24(6): e34479. DOI: 10.2196/34479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agteren J van, Iasiello M, Lo L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing. Nat Hum Behav 2021; 5: 631–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivandic I, Freeman A, Birner U, et al. A systematic review of brief mental health and well-being interventions in organizational settings. Scand J Work Environ Health 2017; 43: 99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med 2015; 45: 11–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanisch SE, Twomey CD, Szeto ACH, et al. The effectiveness of interventions targeting the stigma of mental illness at the workplace: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2016; 16: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang-Schweig M, Kviz FJ, Altfeld SJ, et al. Building a conceptual framework to culturally adapt health promotion and prevention programs at the deep structural level. Health Promot Pract 2014; 15: 575–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harper Shehadeh M, Heim E, Chowdhary N, et al. Cultural adaptation of minimally guided interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Ment Heal 2016; 3: e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davey C, Hassan S, Cartwright N, et al. Designing evaluations to provide evidence to inform action in new settings. London: CEDIL Inception Paper Nº 2, 2018. https://cedilprogramme.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Designing-evaluations-to-provide-evidence.pdf (accessed 22 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alvarez-Galvez J, Rodero-Cosano ML, García-Alonso C, et al. Changes in socioeconomic determinants of health: comparing the effect of social and economic indicators through European welfare state regimes. J Public Heal 2014; 22: 305–311. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shepherd J, Olaya B, Gevaert J, et al. Design, development and pre pilot testing of a digital intervention to improve mental health and wellbeing in the workplace (EMPOWER). 2021.

- 46.Najder A, Merecz-Kot D, Wójcik A. Relationships between occupational functioning and stress among radio journalists – assessment by means of the psychosocial risk scale. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2016; 29: 85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leka S, Jain A, Cox T, et al. The development of the European framework for psychosocial risk management: PRIMA-EF. J Occup Health 2011; 53: 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Godin I, Kittel F, Coppieters Y, et al. A prospective study of cumulative job stress in relation to mental health. BMC Public Heal 2005; 5: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.LaMontagne AD, Keegel T, Louie AM, et al. Job stress as a preventable upstream determinant of common mental disorders: a review for practitioners and policy-makers. Adv Ment Health 2010; 9: 17–35. https://doi.org/105172/jamh9117 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med 2002; 64: 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Central Bureau of Statistics. Eurostat morbidity statistics, pilot data collection, https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/background/2020/44/eurostat-morbidity-statistics-pilot-data-collection (2020).

- 54.Bouwmans C, Krol M, Severens H, et al. The iMTA productivity cost questionnaire: a standardized instrument for measuring and valuing health-related productivity losses. Value Heal 2015; 18: 753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beck AT. Cognitive therapy: nature and relation to behavior therapy – republished article. Behav Ther 2016; 47: 776–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ellis A. The revised ABC’s of rational-emotive therapy (RET). J Ration Cogn Ther 1991; 9: 139–172. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lokman S, Volker D, Zijlstra-Vlasveld MC, et al. Return-to-work intervention versus usual care for sick-listed employees: Health-economic investment appraisal alongside a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open 2017; 7(10): e016348. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Volker D, Zijlstra-Vlasveld MC, Brouwers EPM, et al. Return-to-work self-efficacy and actual return to work among long-term sick-listed employees. J Occup Rehabil 2015; 25: 423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mcgreevy J, Orrevall Y, Belqaid K, et al. Reflections on the process of translation and cultural adaptation of an instrument to investigate taste and smell changes in adults with cancer. Scand J Caring Sci 2014; 28: 204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Resnicow K, Soler R, Braithwaite RL, et al. Cultural sensitivity in substance use prevention. J Community Psychol 2000; 28: 271–290. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mohler P, Dorer B, de Jong J, et al. Translation: overview. In: Survey Research Center (Institute for Social Research) (ed) Guidelines for best practice in cross-cultural surveys. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2016, pp. 233–285. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown CA, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge trial design: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006; 6: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Copas AJ, Lewis JJ, Thompson JA, et al. Designing a stepped wedge trial: Three main designs, carry-over effects and randomisation approaches. Trials; 2015; 16: 352. DOI: 10.1186/s13063-015-0842-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2007; 28: 182–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.European Commission. User guide to the SME definition. Epub ahead of print 2020. DOI: 10.2873/255862.

- 66.Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, et al. Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3: 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moerbeek M, Van Breukelen GJP, Berger MPF. Optimal experimental designs for multilevel logistic models. J R Stat Soc Ser D Stat 2001; 50: 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 68.European Commission. General Data Protection Regulation, http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/2016-05-04 (2016).

- 69.Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, et al. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. Br Med J; 2015; 350: h391. DOI: 10.1136/BMJ.H391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983; 24: 385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med 2001; 2: 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003; 35: 1381–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Topp CW, Østergaard SD, Søndergaard S, et al. The WHO-5 well-being index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom 2015; 84: 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011; 20: 1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van Krugten FCW, Busschbach JJV, Versteegh MM, et al. The mental health quality of life questionnaire (MHQoL): development and first psychometric evaluation of a new measure to assess quality of life in people with mental health problems. Qual Life Res 2021; 1: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bouwmans C, Hakkaart- van Roijen L, Koopmanschap M, et al. Handleiding iMTA medical cost questionnaire (iMCQ). Rotterdam iMTA, Erasmus Univ Rotterdam.

- 77.Ramsey SD, Willke RJ, Glick H, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials II - an ISPOR good research practices task force report. Value Heal 2015; 18: 161–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Manca A, Hawkins N, Sculpher MJ. Estimating mean QALYs in trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis: the importance of controlling for baseline utility. Health Econ 2005; 14: 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jones KC, Burns A. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2021. Kent, UK: Personal Social Services Research Unit, 2021. Epub ahead of print 2021. DOI: 10.22024/UniKent/01.02.92342. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pawson R, Tilley N. An Introduction to scientific realist evaluation. In: Evaluation for the 21st century: a handbook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., 2013, pp. 405–418. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lattie EG, Stiles-Shields C, Graham AK. An overview of and recommendations for more accessible digital mental health services. Nat Rev Psychol 2022; 1: 87–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meyerowitz-Katz G, Ravi S, Arnolda L, et al. Rates of attrition and dropout in app-based interventions for chronic disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22(9): e20283. DOI: 10.2196/20283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076221131145 for Study protocol of EMPOWER: A cluster randomized trial of a multimodal eHealth intervention for promoting mental health in the workplace following a stepped wedge trial design by Beatriz Olaya, Christina M. Van der Feltz-Cornelis and Leona Hakkaart-van Roijen, Dorota Merecz-Kot, Marjo Sinokki, Päivi Naumanen, Jessie Shepherd, Frédérique van Krugten, Marleen de Mul, Kaja Staszewska, Ellen Vorstenbosch, Carlota de Miquel, Rodrigo Antunes Lima, José Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Luis Salvador-Carulla, Oriol Borrega, Carla Sabariego, Renaldo M. Bernard, Christophe Vanroelen, Jessie Gevaert, Karen Van Aerden, Alberto Raggi, Francesco Seghezzi, Josep Maria Haro in Digital Health