Abstract

Objectives

In the context of a growing number of dementia friendly communities (DFCs) globally, a need remains for robust evaluation, and for tools to capture relevant evidence. This paper reports the development of a suite of evaluation resources for DFCs through a national study in England.

Methods

Fieldwork took place in six diverse case study sites across England. A mixed methods design was adopted that entailed documentary analysis, focus groups, interviews, observations, and a survey. Participants were people affected by dementia and practice-based stakeholders. A national stakeholder workshop was held to obtain input beyond the research sites. A workshop at the end of the study served to check the resonance of the findings and emerging outputs with stakeholders from the case study DFCs.

Results

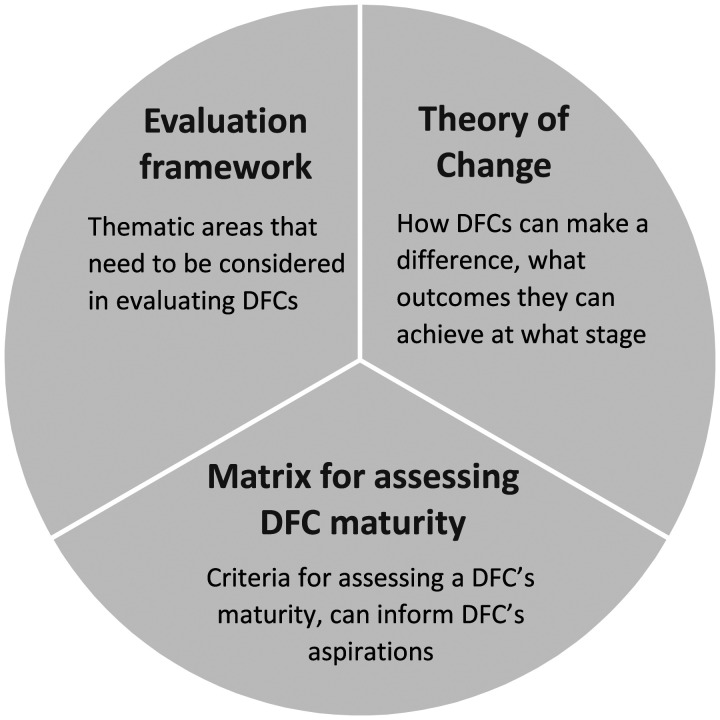

The study had three key outputs for the evaluation of DFCs: First, an evaluation framework that highlights thematic areas to be considered in evaluating DFCs. Second, a Theory of Change that presents inputs into a DFC and short, medium and longer term outcomes. Third, a matrix for assessing a DFC’s degree of maturity, which enables a sense of the kinds of outcomes a DFC might realistically aspire to. These three outputs form a suite of interlinking and complementary evaluation resources for DFCs.

Conclusions

The study has contributed evidence-based resources for monitoring and evaluation that complement existing frameworks. They can be applied to arrive at a detailed assessment of how well a DFC works for people affected by dementia, and at insights into the underlying factors that can guide future policy and practice.

Keywords: dementia friendly communities, evaluation, monitoring, people affected by dementia, mixed methods

Introduction

In the global context of greater numbers of people living with dementia (Alzheimer Europe, 2019; Prince et al., 2015; World Dementia Council, 2020), dementia friendly communities (DFCs) have become an increasingly visible response. While there is no universally accepted definition of DFCs, they share a concern with ensuring that people affected by dementia (people living with dementia, and carers and supporters) can live well and continue to be active and valued citizens. In England, backed by government policy (Department of Health, 2012, 2015) and an official recognition process (Alzheimer’s Society, 2013, 2014-15, 2018; British Standards Institution, 2015; World Dementia Council, 2020), the number of DFCs has grown extensively in recent years (Buckner et al., 2019a). At the time of writing, there were 351 officially recognised DFCs (Dementia Friends, 2020). Community-based dementia friendly initiatives have also expanded across the world (see e.g. Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2016, 2017), and dementia friendly activities can be identified in over 90% of OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries (OECD, 2018). The development of dementia friendly initiatives globally is being promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO), which has published a practical toolkit to support relevant efforts (WHO, 2021).

As recent international reports illustrate (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2016, 2017; World Dementia Council, 2020), DFCs come in different shapes and sizes. A scoping study by the authors has identified a wide variety of origins, organisational characteristics, and ways of operating among DFCs in England. While the majority are defined by their geographical location, some are Communities of Interest organised around shared identities, interests and places (e.g. churches, shopping centres, airports, national high street banks). Their activities differ, although for many, raising awareness of dementia is a priority. Many location-based DFCs have their origins in Dementia Action Alliances (Dementia Action Alliance, 2020) – local agencies and businesses working together to raise awareness and promote best practice in dementia care and support.

Robust evaluation and the development of appropriate resources to facilitate monitoring of impact has not kept pace with the proliferation of DFCs. Evaluations of DFCs have often concentrated on the process of becoming a DFC, barriers and facilitators, and perceived benefits. They are largely descriptive, with a focus on numbers of DFC initiatives and levels of participation in activities (Hare & Dean, 2015; Hebert & Scales, 2017; Shannon et al., 2019). Despite notable exceptions (Coyle, 2018; Fleming & Bennett, 2017; Fleming et al., 2017), a need remains for evidence on DFC effectiveness and sustainability, and for tools that can capture such evidence. Evaluation tools need to accommodate the diversity and context-specific nature of DFCs. At the same time, they need to offer categories for assessment and indicators whose relevance is shared across DFCs.

This article is based on a national study in England. The study asked how different types of DFCs enable people affected by dementia to live well, what is needed to sustain them, and how their work can be monitored and evaluated. It was a mixed methods study in three phases: mapping of DFCs in England and an online scoping study of 100 sample DFCs (Phase 1); pilot testing in two DFCs of an existing evaluation tool that had been adapted from a tool for Age-Friendly Cities (Phase 2); application of the evolving evaluation tool in six case study sites (the two pilot DFCs, and two further DFCs) (Phase 3) (Buckner et al., 2019a; Darlington et al., 2020; Woodward et al., 2018).

Reported here is the development of the evaluation tool (later called ‘framework’; see below), and of two complementary evaluation resources for DFCs – a Theory of Change and a matrix for assessing DFC maturity. This involved a process of testing and co-production that benefited from the expertise of people affected by dementia and practice-based stakeholders (Phases 2 and 3).

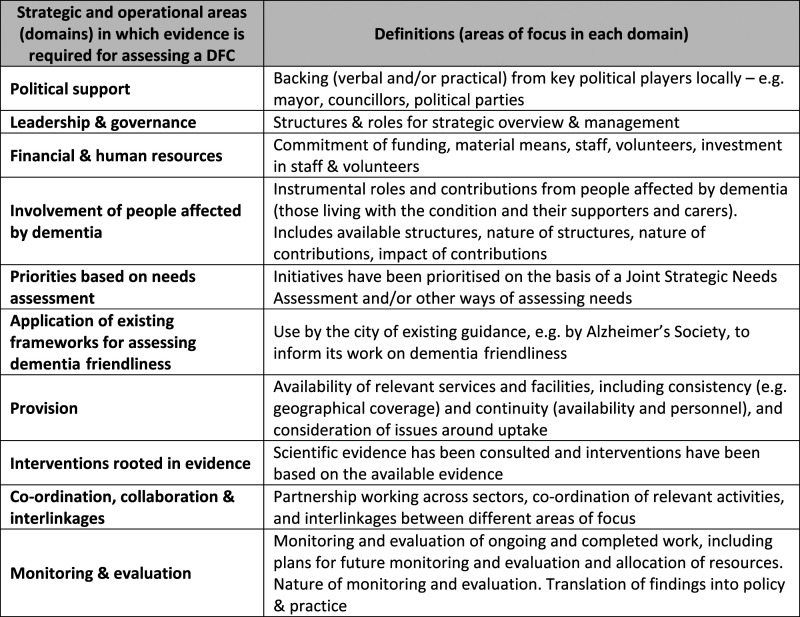

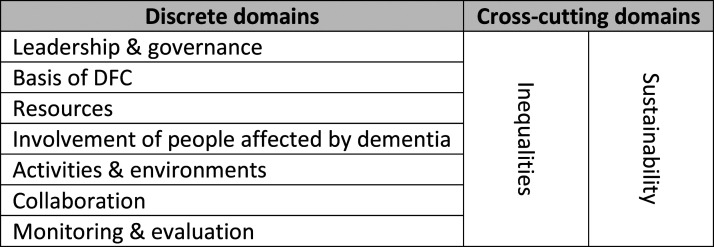

DEMCOM initially drew on an evaluation tool that had its origins in an instrument developed for assessing Age-Friendly Cities, in line with WHO’s Age-Friendly Cities initiative (Buckner et al., 2017; Buckner et al., 2019b; WHO, 2007a, 2007b). While age-friendliness and dementia friendliness are related, they are not the same (Buckner, 2017; Turner & Morken, 2016). The Age-Friendly Cities tool had undergone minor modifications to ensure a dementia-specific focus in a small pilot study of a DFC prior to the DEMCOM study (Buckner et al., 2018): The focus of the original Age-Friendly Cities tool on ‘older people’ and ‘age-friendliness’ had been replaced by a focus on ‘people affected by dementia’ and ‘dementia friendliness’ – as obvious adjustments that could be made before an evidence base for the design of a fully dementia-specific instrument was available. The resulting tool in the pilot study consisted of ten strategic and operational areas or ‘domains’ – the latter had been identified as areas in which evidence was required for assessing a DFC (Figure 1). While the original Age-Friendly Cities tool also integrated data quality assessment, a scoring scale, and a mechanism for visual representation of findings (see Buckner et al., 2018; Buckner et al., 2019b), the DEMCOM study concentrated on utilising the ten domains only. These were compatible with other frameworks that outline key features and building blocks of DFCs: the importance of involvement of people affected by dementia, and the significance of the environment, key stakeholders, resources and networks to increase awareness, create supportive structures and sustain services (e.g. Alzheimer’s Disease International (n.d.); Alzheimer’s Society, 2014-15; British Standards Institution, 2015; Crampton et al., 2012; Heward et al., 2017; Imogen Blood & Associates Ltd and Innovations in Dementia, 2017; Lin, 2017; Wisconsin Healthy Brain Initiative, (n.d).). The ten domains informed data collection in DEMCOM, and provided the basis for the development of evidence-based and co-produced evaluation resources for DFCs.

Figure 1.

Evaluation tool for DFCs based on an instrument for evaluating Age-Friendly Cities at the outset of the DEMCOM study (Buckner et al., 2018).

Methods

Study site selection

The selection of two pilot sites for Phase 2 was informed by the insights from the Phase 1 scoping study. The latter had provided an overview of the diversity of 100 sample DFCs in terms of their histories, populations served, activities, and organisational models. From a shortlist of three of the 100 sample DFCs, which varied on key characteristics and were invited to take part in the study, two welcomed the invitation.

The first pilot site (Site A) was a city with an above average Black and Minority Ethnic population. It had a recently formed Dementia Action Alliance, a cross-sector network of organisations committed to improving the experience of living in the city of people affected by dementia. The DFC initiative worked closely with the Alzheimer’s Society. A local dementia centre served as a hub for most of its activities. The second pilot site (Site B) was a city with a culturally diverse population that was geographically distant from the first site. Its DFC had grown out of an established Dementia Action Alliance. The DFC had weak links with the Alzheimer’s Society. Its activities were dispersed across the city and its neighbourhoods. They built on a history of community engagement and activism with older populations.

The six case study sites in Phase 3 included the two pilot sites, plus four geographically defined DFCs from the sample of 100 DFCs in Phase 1 (Sites C-F). The latter were purposively selected to ensure diversity in terms of location (region in England), socio-demographic make-up, underpinning values and motivations, operational approach, and distinctive features (e.g. serving a diverse community). DFCs in London were excluded from the sampling for Phase 3, as the Mayor’s Office at the time was co-ordinating cross-borough initiatives to establish the first dementia friendly capital. Out of 33 shortlisted DFCs, 13 responded to an invitation for expressions of interest. Consideration of the opportunities for learning offered by the 13 different DFCs led to a consensus among the research team on five DFCs as potential sites. Renewed contact with the latter resulted in the recruitment of the four sites whose commitment to participating appeared strongest. They included one borough that in turn incorporated a growing number of spatially concentrated DFCs, one city, one large town, and one market town and parish.

Data collection

In Phase 2, the evaluation tool described above was pilot tested in two sites. The aim was to develop it into a DFC-specific evaluation framework. The ten tool domains, together with the findings from Phase 1 on key DFC characteristics, guided data collection.

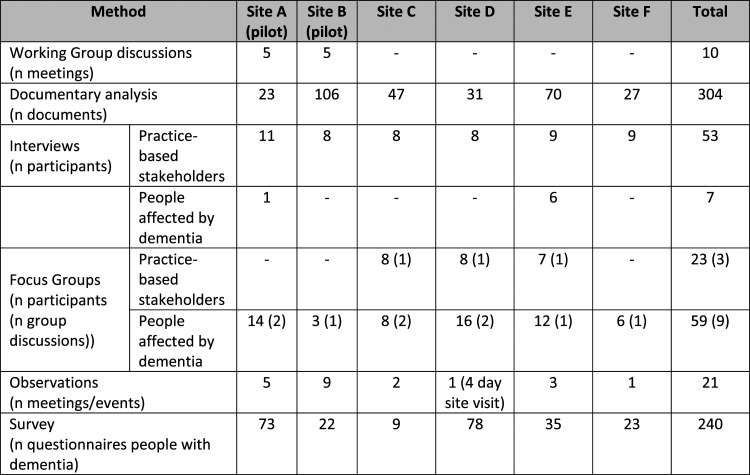

At this stage, mainly qualitative information was collected through diverse methods (Figure 2), with an emphasis on input from people affected by dementia and practice-based stakeholders. In each site, five working group discussions took place that involved professionals in policy and commissioning roles, voluntary sector workers, staff from local services, representatives of minority groups, volunteers, and people affected by dementia. Participant numbers in the group discussions ranged from two to 16. The discussions focused on the relevance of the ten tool domains, potential data sources, and emerging findings.

Figure 2.

Overview of data collection in Phases 2 and 3.

Documentary analysis of evidence that was obtained through online searches and local stakeholders was carried out. A total of 23 and 106 documents collected in Sites A and B respectively included health needs assessments, minutes of Dementia Action Alliance meetings, timetables of DFC activities, and evaluation reports of interventions. The substantially higher number of documents in Site B is attributed to proactive information sharing by a key stakeholder there, as well as the site’s longer history of working as a DFC.

In Sites A and B, semi-structured interviews with stakeholders in policy and practice were conducted by telephone or face-to-face. The participants included representatives from the public, voluntary and private sectors, as well as self-employed individuals, elected local representatives, and volunteers. The interviews focused on strategic and operational aspects of the DFCs. While interviews with persons living with dementia had not been envisaged for Phase 2, in Site A an opportunity arose, leading to one semi-structured interview on the participant’s experience of living in a DFC.

People affected by dementia participated in focus groups in each site. In one instance, a person living with dementia acted as facilitator. Additional evidence was collected through observations, for example, of Dementia Action Alliance meetings.

A national stakeholder workshop was hosted in London at the end of Phase 2 (February 2018). The 39 delegates included people living with dementia (n = 9), carers and supporters (n = 6), policy and practice stakeholders and members of advocacy groups (n = 7), and researchers (n = 17). In facilitated group sessions, the participants discussed whether the different tool domains were sufficiently well defined, and what the key criteria for a ‘good’ DFC were in each domain. Their input informed the next iteration of the evolving evaluation tool.

In Phase 3, the revised tool guided data collection in the six case study sites. Mixed methods were used (Figure 2). DFC activities and meetings were observed in each site, and documentary evidence was collected. Semi-structured interviews with stakeholders in policy and practice were carried out, and in Site E, opportunities for semi-structured interviews with people affected by dementia arose spontaneously. Focus groups with people affected by dementia took place. In Sites C-E, focus groups were run where key stakeholders in policy and practice discussed the findings presented in site-specific interim reports.

A survey of people living with dementia who were not actively involved in the running or planning of the local DFC was conducted in Phase 3 across the six sites. The aim was to gain insights into the reach of the DFCs, and how participants experienced living in a DFC. Questionnaires were distributed in partnership with Local Clinical Research Networks, and through Join Dementia Research, research databases held at memory clinics, and medical practices. In one site, questionnaires were distributed through the Alzheimer’s Society. Responses were collected by post or over the phone (Darlington et al., 2020).

Consent was sought from the participants for the interviews and group discussions to be audio-recorded and transcribed. Particular attention was paid to ongoing consent from participants living with dementia (Dewing, 2007). With the exception of one interview, where the participant agreed to notes being taken, consent for audio recording was obtained in all instances.

Data analysis

The qualitative data from Phases 2 and 3 were analysed thematically, supported by the use of NVivo V12 for data management. Data from different sources enabled triangulation. Analysis was guided by the domains of the evolving evaluation tool. A coding tree was created a priori with nodes that matched the domains, and sub-nodes for each domain that allowed for a more refined analysis. As more data became available, the nodes and sub-nodes were revised, and data were coded and re-coded iteratively. This in turn shaped the further development of the evaluation tool.

The coding was split between six researchers, and regular cross-checking occurred. Disagreements were discussed and resolved within the team. At an advanced stage of the analytic process, individual researchers were allocated different domains of the evolving evaluation tool for which to prepare a preliminary account of findings. A workshop with all team members was held to discuss coding and interpretation of findings, and implications for the evaluation tool.

The survey data were managed and analysed in SPSS V25. Descriptive statistics were produced. Data from open questions were analysed thematically in line with the above (Darlington et al., 2020).

Stakeholder feedback

At the end of the study, a workshop was held with 30 delegates linked to the case study DFCs. The aim was to check the resonance of the study findings and the usability of the emerging evaluation resources. The participants mainly included professionals and volunteers working in and with the DFCs. While people affected by dementia were also represented, most of the participants in this group were carers and supporters. Only one participant was living with dementia, although several people living with dementia had been invited.

Results

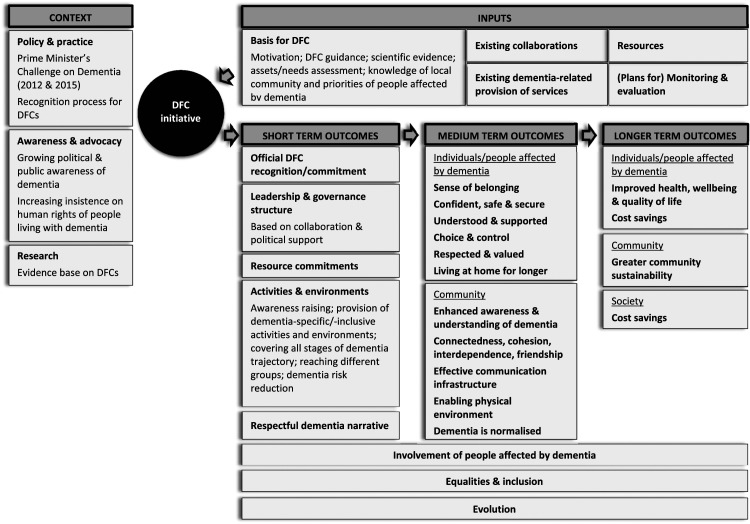

This section demonstrates how the emerging findings have shaped the development of a suite of interlinking evaluation resources for DFCs: an evaluation framework based on the initial evaluation tool, a Theory of Change, and a matrix for assessing DFC maturity (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Suite of evaluation resources for DFCs.

Evaluation framework

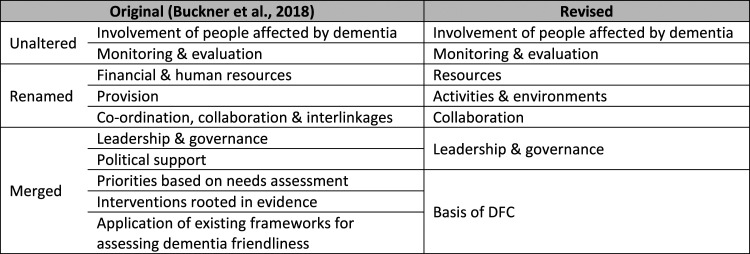

Analysis of the data from the two pilot sites in Phase 2 led to initial revisions to the evaluation tool (see Figure 4). Of the original ten domains, two (‘Involvement of people affected by dementia’; ‘Monitoring & evaluation’) remained unaltered. Three (‘Financial & human resources’; ‘Provision’; ‘Co-ordination, collaboration & interlinkages’) were renamed without altering their content substantially, in order to make the domain names more concise and intuitive. Five were merged into two new domains: Political support’ became part of ‘Leadership and governance’, as the emerging evidence had shown the relevance of political support for the strategic direction and way forward for a DFC. ‘Priorities based on needs assessment’, ‘Interventions rooted in evidence’ and ‘Application of existing frameworks for assessing dementia-friendliness’ all were subsumed under a new domain called ‘Basis of DFC’. The latter was designed to capture anything that provided a foundation for a DFC’s work (e.g. motivations; needs and assets assessments; local priorities; official guidance by the Alzheimer’s Society on creating DFCs; scientific evidence) in one single domain.

Figure 4.

Initial revisions to the evaluation tool based on analysis of Phase 2 data.

Analysis of the pilot site data also resulted in the addition of two broader domains that were relevant across the seven redefined and discrete domains of the tool. The first of these ‘cross-cutting domains’ was labelled ‘Inequalities’. It was based on evidence that indicated the need to pay attention to potential imbalances within a DFC. For example, the geographical locations of services affected access to DFC activities. In one site, DFC activities predominantly took place in a dedicated venue, which meant they were less accessible to users who lived further afield and/or did not have access to private transport. Also, data from both pilot DFCs suggested a very limited reach of specific groups:

… with [involvement group for people affected by dementia] … we’re getting people, mainly white, mainly that can get on the bus into town, mainly that come to other events, so hear by word of mouth, so we know that we’re missing people from BAME communities, … people that are frail …

(Site B; practice-based stakeholder)

The second cross-cutting domain, ‘Sustainability’, was developed on the basis of data that suggested that consistency and continuity regarding different aspects of a DFC was important. For instance, both pilot sites had experienced funding insecurity, and loss of key staff and volunteers. This had interfered with the planning and delivery of DFC activities. The data also highlighted the critical importance of continuity in strategic leadership, and in formalised and practical support from the local authority and other centrally funded local services:

… [the Dementia Action Alliance was] progressing at an incredible rate with [name] who was the council employee heading us up … it was his part of his role and his job. And then he got another job … and at that point the council said, ‘You’re on your own, we’re all in favour of it but we won’t be putting a council employee into place.’

… the council involvement is the thing that we really are striving to get back.

(Site A; Dementia Action Alliance Vice Chair)

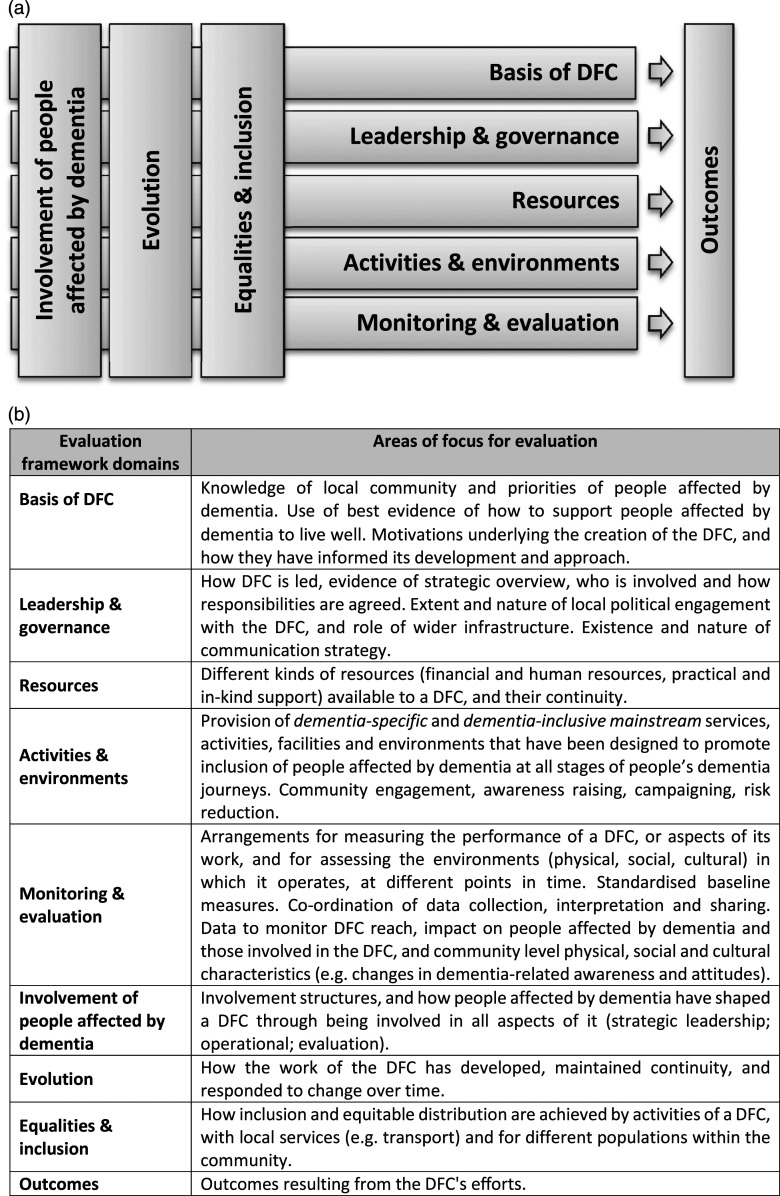

The evaluation tool developed on the basis of Phase 2 findings is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Revised evaluation tool based on Phase 2 findings.

These tool domains broadly resonated with the participants in a national stakeholder workshop. At the same time, there was a consensus among the participants on the need to adjust the cross-cutting domains. It was suggested that ‘Inequalities’ should be renamed ‘Equalities’, as the use of positive language would be consistent with the message of DFCs and the tone of the study. Also, ‘Sustainability’ was viewed critically, as it was felt to have connotations of maintaining a status quo. ‘Evolution’ was advocated as a less restrictive alternative that reflected the dynamic nature of DFCs and was better suited to capturing aspirations and development beyond existing levels of achievement. Workshop participants also argued that ‘Involvement of people affected by dementia’ needed to be a cross-cutting domain, reflecting the fact that all aspects of a DFC are fundamentally about people affected by dementia and require their contributions. The proposed changes were compatible with the emerging findings, and they resonated with the researchers’ understanding of DFCs.

Evidence from the case studies in Phase 3 suggested further modifications to the tool. The researchers noted that data on inclusion could sit comfortably with data relating to equality issues. Accordingly, the cross-cutting domain ‘Equalities’ was renamed ‘Equalities and inclusion’. They also agreed that the domain ‘Collaboration’ was redundant. Relevant evidence tended to be readily accommodated in other domains where it had, in fact, often been coded additionally, particularly in ‘Leadership and governance’ and ‘Activities and environments’. For example, the following statement can be seen as relating to both collaboration and leadership and governance:

The Dementia Steering Group continues to go through from strength to strength with a wide variety of statutory and non statutory organisations being members. The most recent organisation to join is the [regional] Ambulance Service. Other representatives who attend come from housing, health, third sector, CEC partnerships, procurement and Trading Standards amongst many others.

(Site E; documentary evidence)

Finally, it became apparent that while the evaluation tool was strong at identifying processes and structures, it was not capturing outcomes from DFC work in a sufficiently explicit way. This had been observed by the researchers during data collection, and it had also been raised at the stakeholder workshop. The data highlighted that DFCs’ work had outcomes that related to the different tool domains. In order to ensure a systematic way of capturing outcomes, it was decided that they needed to be considered explicitly under each of the domains.

The process described has resulted in an evidence-based and co-produced evaluation framework for DFCs (Figure 6a). The areas of focus of each framework domain (Figure 6b), which indicate issues to be considered in evaluating a DFC, have been shaped by the findings from the research sites and supported by the literature. For example, the findings suggested the importance of DFCs simultaneously making mainstream services more inclusive for people living with dementia (‘dementia-inclusive’), and providing ‘dementia-only’ services (‘dementia-specific’) – a point also raised by Dean et al. (Buckner et al., 2019a; Dean et al., 2015a, 2015b). In addition, the areas of focus for evaluation have been shaped by a consensus among the participants of the national stakeholder workshop on key criteria for a ‘good’ DFC that evaluation needs to capture. The latter include that i) people affected by dementia are involved in all aspects of the DFC (strategic leadership; operational; evaluation); ii) the DFC provides a range of services and activities that cover all stages of people’s dementia journeys; iii) there is strong local political engagement with the DFC; and iv) there is continuity of resources.

Figure 6.

(a) The evaluation framework for DFCs – final iteration. b. Areas of focus of the evaluation framework domains.

Theory of Change

The evaluation framework works in conjunction with a Theory of Change for DFCs that was developed as part of the study. The case study DFCs operated in different contexts, and they were at different stages of development. These factors – local context, and stage of development – played a critical role in shaping the outcomes of their work and their aspirations for the foreseeable future. The insights from the case studies, together with literature that highlights personal- and collective-level outcomes from the work of DFCs (e.g. Alzheimer’s Disease International (n.d.); Harding et al., 2019), have informed a Theory of Change that presents inputs into a DFC and short, medium and longer term outcomes (Figure 7/Appendix I).

How inputs were identified is illustrated by the following excerpt from a focus group discussion among stakeholders in Site E, which drew attention to motivations for becoming dementia friendly:

P01: … [the local DFC] calls itself the little town with a big heart and it definitely is, … so I would say [the motivation is compassion].

P02: … I have also seen some businesses now starting to appear and they’re thinking actually there’s a real good business reason for doing this, … they’re interested in their balance sheet ...

(Site E; stakeholder Focus Group)

In the analytic process, ‘motivations for becoming dementia friendly’ came to be understood as an important consideration in a DFC’s development. Captured by the ‘Basis of DFC’ domain, it can be described as an ingredient, or input, to be reflected in the Theory of Change.

The data also provided evidence of outcomes that are directly attributable to specific interventions or particular aspects of a DFC’s work – in this quote, the outcomes are friendship and social connectedness among the members of a social group for people affected by dementia:

… we see a community that are more connected, and whether they’re more resilient because of the friendships … the social interactions. … [the group for people affected by dementia], that really is a little family now. They organise trips out and different things, that social, the benefits of having somebody to call on, or to understand, or to look after the loved one while they go and do. All of that happens on a daily basis now, and that wasn’t there before.

(Site E; practice-based stakeholder)

At the same time, there were outcomes that were linked more broadly to the overall DFC initiative – for instance, enhanced awareness of dementia:

Now when you go around the town now, the dementia friendly signs, they’re all over the place. And people who have never been trained will understand if you’ve got dementia, the carers feel more comfortable taking people out.

(Site D; Focus Group with carers)

The Theory of Change appears to describe linear processes of DFC development. Rather than an accurate reflection of reality, this is a feature of the – necessarily simplified – representation of the inherent complexity of DFCs. The case studies indicated causal mechanisms in the DFCs’ evolution that entailed circular processes and feedback loops. For example, as became apparent particularly in Sites A and B, provision of activities for people living with dementia (short-term outcome) led to participants feeling confident and valued (medium-term outcome), which in turn enabled them to voice their views on services and activities and, thus, shape provision (short-term outcome). Investment of resources, particularly in terms of volunteer time (input), preceded the sites’ commitment to becoming DFCs (medium-term outcome), which in turn mobilised further volunteer contributions (input).

The Theory of Change indicates what DFCs might achieve at different stages of their journeys. It can thus guide monitoring and evaluation, as well as efforts to identify priorities for policy and practice, while taking account of a DFC’s individual circumstances.

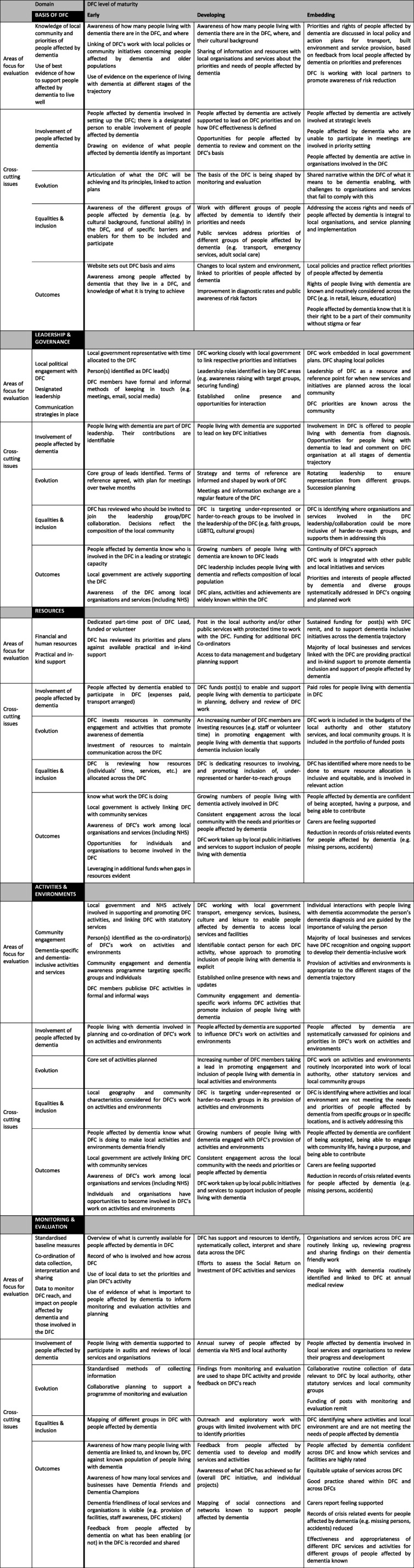

Matrix for assessing DFC maturity

The study findings have also enabled the design of a user-friendly resource for DFC (self-)assessment that can complement the evaluation framework and the Theory of Change. This takes the form of a matrix built around the evaluation framework domains (Figure 8/Appendix II). It provides domain-specific criteria to assess the degree of maturity of a DFC. A distinction is made between three levels of DFC maturity – ‘early’, ‘developing’ and ‘embedding’ – that reflect the stages of development observed in the case study DFCs. For example, in the ‘Leadership and governance’ domain, one of the criteria that would place a DFC in the ‘early’ category is the presence of a ‘local government representative with time allocated to the DFC’. A criterion for the more advanced ‘embedding’ stage is: ‘DFC work embedded in local government plans. DFC shaping local policies’. The matrix was developed on the basis of key characteristics of the case study DFCs, and evidence of the kinds of aspirations and outcomes that these enabled.

Discussion

An issue that continues to emerge in discussions with stakeholders is that DFCs are struggling with assessing their achievements and impact. This is due partly to capacity, but partly also to gaps in knowledge and expertise. From a global perspective, the World Dementia Council has emphasised the need for ‘a better understanding of the evidence base for dementia friendly initiatives’ (World Dementia Council, 2020, 3). The evidence base will be strengthened by the availability of evaluation resources such as those that have resulted from DEMCOM. While developed in an English context, these resources can be adapted to DFCs beyond England, as appropriate to local contexts. They might be applied in combination with instruments such as the WHO toolkit (WHO, 2021) to support the development of DFCs as well as the building up of a robust evidence base of their impact.

A key output from the study is an evidence-based evaluation framework for DFCs that is based on in-depth case studies and consultation with practice-based stakeholders and people affected by dementia. It identifies strategic and operational areas where monitoring and assessment should focus if DFCs are to work well for people affected by dementia, and if they are to be sustained. The framework has informed, and can be used in conjunction with, further study outputs – a Theory of Change for DFCs, and a matrix for assessing DFC maturity. The combined use of these resources can result in a detailed picture of strengths in a DFC’s work and areas for improvement, and insights to guide priority setting and future policy and practice.

The depiction of the matrix (Figure 8/Appendix II) is necessarily simplified and thus obscures that there can be considerable overlap between the criteria for the different degrees of DFC maturity. Also, in the messy reality of a DFC’s journey, the criteria do not necessarily follow a linear progression. Progress in a DFC’s development can stall and even revert to earlier stages as, for example, key players move on, or resources diminish – a fact illustrated by the experiences of the pilot sites. Nevertheless, delineating clear criteria for degree of DFC maturity is useful for analytic purposes, as well as for demonstrating the principle of assessing DFC maturity, and they can enable an enhanced sense of a DFC’s stage of development. Assessing a DFC’s level of maturity, and considering this in relation to the Theory of Change, can support well-informed and realistic planning by the DFC. It can help with identifying priorities that are appropriate to the DFC’s specific situation. It can enable the DFC to focus on further inputs required, and on outcomes that it can realistically aspire to, as well as timeframes for their delivery. These can be integrated into policy and practice. For example, if a DFC’s degree of maturity in the ‘Activities & environment’ domain is ‘early’, a realistic short-term outcome would be provision of a (growing) number of dementia-related activities, including raising awareness of dementia. As the DFC reaches the ‘embedding’ level, one might reasonably expect enhanced awareness and understanding of dementia in the community as a medium-term outcome.

The Theory of Change, together with the matrix, can provide a detailed understanding of DFC achievement. It can guide measurement of outcomes, which can be assessed against a DFC’s level of maturity, thus providing an indication of a DFC’s performance in relation to its specific circumstances.

The suite of evaluation resources, and the matrix and Theory of Change in particular, focus attention on the complex and dynamic nature of DFCs. By emphasising sensitivity to a DFC’s degree of maturity, they promote a realistic approach in DFC planning, target setting, and monitoring and evaluation that reflects the resources and opportunities available.

Within the study, it was possible to use the matrix to establish the maturity of the six case study DFCs in the various domains, identify missing data, and demonstrate how the involvement of key personnel and organisations informed the development and design of dementia enabling work. At a final workshop, findings were presented for sense checking and discussion to participants from the case study DFCs. The participants appreciated the organisation of findings by domain, which meant that they could focus on strengths of the DFCs, on reasons why certain DFC initiatives had not been sustained, and on the kind of data needed to review progress. More generally, the participants agreed that there was an urgent need for user-friendly evaluation resources for DFCs, and that the current study had made an important contribution to addressing this.

Cross-sector and cross-agency collaboration are widely recognised as critical to the success of DFCs (Alzheimer’s Society, 2014-15, 2018; British Standards Institution, 2015; Goodman et al., 2019; Green & Lakey, 2013). This entails co-ordination of provision of services, and of monitoring and evaluation activities. DFCs can draw on the evaluation resources developed through the study to structure information exchange, agree on goals, identify indicators, and co-ordinate data collection and analysis among their members.

A recurring issue in discussions of DFC evaluation is the notion of comparison of DFCs, both within and across countries. The study evaluation resources support intra-DFC comparison across time. Their consistent use enables a DFC to track its development and achievements. This is important for learning and informing practice, as well as for attracting resources and ensuring accountability to funders.

Comparison across DFCs is more complex. This is highlighted by WHO with regards to Age-Friendly Communities, which have some similarities to DFCs, (Buckner, 2017; Turner & Morken, 2016). WHO’s report on core indicators for Age-Friendly Cities (WHO Centre for Health Development, 2015) draws attention to the fact that the contexts and local conditions of Age-Friendly Cities vary, which affects comparability. Noting that core indicators can facilitate comparison across place, the report argues that ‘[inter-city] comparisons are something to be aspired [sic]’ (WHO Centre for Health Development, 2015, 8) while focusing on intra-city comparison across time. The study findings suggest that while different approaches or DFC models work in different settings, there are key features and mechanisms that are relevant across DFCs. The matrix for assessing DFC maturity is based on such features. It identifies key criteria that have been designed to be sufficiently broad and adaptable to be relevant to differing local contexts. This makes it a tool for inter-DFC comparison. DFCs of similar degrees of maturity in similar contexts can aspire to similar kinds of outcomes. However, further testing of the matrix for the purpose of inter-DFC comparison is needed, particularly beyond the context of England, and there is scope for its further development. By applying a system that allows for inter-DFC comparison, different DFCs can generate comparable data. Such meta-data can enable a better understanding of what it is that makes DFCs work well at scale. Importantly, comparison across DFCs should not be viewed through a competitive lens, but as a mechanism for mutual learning.

A important motivation for DFCs are what Buswell et al. (Buswell et al., 2017) term ‘utilitarian’ or pragmatic considerations – the economic benefits to be gained from being responsive to the increase in numbers of people living with dementia. These benefits (e.g. cost savings arising from DFCs enabling people living with dementia to defer the use of social care services and/or to stay in their own homes for longer) remain largely speculative, as relevant evidence is scarce (though see Green & Lakey, 2013). There is also a paucity of evidence on the resources needed to sustain DFCs and allow them to do effective work that leads to different kinds of outcomes. While not designed as an economic study, the study created evidence-based scenarios to assess comprehensive resource requirements as well as the broader ‘social value’ of DFCs – their social, economic and environmental benefits (Goodman et al., 2019; Public Services (Social Value) Act (2012), 2012; Willis et al., 2018). There has so far been no evidence documenting the actual or potential cost-effectiveness, cost benefit, and social value of DFCs. The evaluation resources developed through the study can provide the necessary building blocks for relevant evaluations if used strategically at an early phase to structure monitoring efforts. As DFC activities progress, they can also serve to document resources used and outcomes achieved, and to demonstrate longer term impact if an appropriate data collection structure is in place.

The study had some limitations. These include the under-representation of people affected by dementia from diverse groups, and those in the later stages of living with dementia – although this reflects who was involved in the DFCs studied. This limited the ability to ensure that the evaluation resources developed adequately reflect the experiences and priorities of different groups, opening up opportunities for further research.

While the study has delivered a suite of evaluation resources, scope remains for further testing and refinement of these. Of relevance here is the scale and nature of a DFC. The case study sites have covered DFCs of different sizes and administrative geographies, on a scale from borough at one end to market town and parish at the other. Yet although the research sites have incorporated local neighbourhoods and small rural DFCs, the evaluation resources have not been applied independently at this very local level. Similarly, their applicability to DFCs that are not geographically defined (Communities of Interest) remains as yet untested.

While the Theory of Change is presented in a format that is often used for Logic Models, its evidence-informed nature distinguishes it from the latter and their hypothetical character (Sharp, 2021). It is, however, worth remembering that the evidence base from the case studies is not exhaustive. The Theory of Change could thus benefit from further collection of research and practice evidence that can inform appropriate revisions.

Given the origins of the evaluation framework in a tool designed for Age-Friendly Cities, the question arises whether the suite of evaluation resources for DFCs may in turn inform Age-Friendly City assessment toolkits. In the context of population ageing, work to explore this would be timely.

Conclusion

The continuing growth of DFCs in England and internationally needs to be supported by up-to-date evidence on their effectiveness and on how they can be sustained. This calls for well-designed evaluation resources. The study has contributed evidence-based resources for monitoring and evaluation that complement existing frameworks. They can be applied to arrive at a detailed assessment of how well a DFC works for people affected by dementia, and at insights into the underlying factors that can guide future policy and practice.

There is value in using evaluation resources to track DFCs’ progress and identify indicators of impact over time. Both internal monitoring and, ultimately, comparison of outcomes achieved by DFCs of similar degrees of maturity in key areas of work will demonstrate how DFCs are changing the environment and everyday experience of people affected by dementia. Efforts to ensure that the necessary tools and approaches are available must continue with some urgency.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the study participants and individuals who supported the delivery of this research.

Biography

Stefanie Buckner is a Research Associate at Cambridge Public Health, University of Cambridge. Stefanie’s research interests include Age-Friendly and Dementia Friendly Cities and Communities and their evaluation, health inequalities, place-based approaches to population health, and the involvement of members of the public in health research.

Louise Lafortune is a Principal Research Associate at Cambridge Public Health, and co-leads of its Lifecourse and Ageing research pillar. Louise believes older people should be able to live full, engaged lives in their chosen communities. Her work targets systems, interventions and technologies that help people maintain their independence and quality of life as they age.

Nicole Darlington is a Senior Research Assistant at the University of Hertfordshire working on the Applied Research Collaboration East of England. Nicole’s research interests include social networks of people affected by dementia, community engagement work that enables and supports people affected by dementia, and dementia friendly communities.

Angela Dickinson is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Research in Public Health and Community Care (CRIPACC) in the University of Hertfordshire. Angela’s research interests include the health and well-being of older people with a particular focus on food security and creative and inclusive research methods and public engagement.

Anne Killett is a Senior Lecturer in Occupational Therapy at the University of East Anglia. Anne’s research concerns the respectful care of older people, and she is particularly interested in participative or collaborative approaches to research.

Elspeth Mathie is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Research in Public Health and Community Care (CRIPACC). Her research has focused on older people including NIHR funded studies in care homes, end of life care and dementia. Elspeth has been co-lead of the Inclusive Involvement theme (Patient and Public Involvement) at NIHR Applied Research Collaboration East of England since 2016.

Andrea Mayrhofer is a Senior Research Fellow with the Applied Research Collaboration North East North Cumbria. Her research focuses on vulnerable populations, community, and society. Recent work has focused on Dementia Friendly Communities, dementia care and post-diagnostic social care support for individuals and families affected by young onset dementia.

Michael Woodward is a Visiting Research Associate at the University of East Anglia. Michael has an interest in research surrounding the care of older people and how society can help support older people and people living with dementia.

Claire Goodman is a Professor of Health Care Research and NIHR Senior Investigator at the University of Hertfordshire. Claire’s research interests include research with older people with complex needs (including dementia) living at home and in long-term care settings, integrated working across health and social care for older people and their families, community engagement activities that support people affected by dementia to live well.

Appendix 1.

Figure 7.

Theory of Change for DFCs.

Appendix 2.

Figure 8.

Matrix for assessing DFCs maturity.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This is a summary of research supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East of England. This study was a collaboration between three universities that are all part of the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) East of England: the University of Hertfordshire, the University of East Anglia and the University of Cambridge. Claire Goodman is a NIHR senior investigator. Nicole Darlington, Anne Killett, Louise Lafortune, Elspeth Mathie and Claire Goodman receive funding from the Applied Research Collaboration East of England.

Authors’ note: The paper is based on the National Evaluation of Dementia Friendly Communities in England (DEMCOM Study, January 2017–June 2019). This name has been replaced by ‘a national study’ or ‘the study’, as appropriate.

Antony Arthur is a Professor of Nursing Science at the University of East Anglia. He has a background in general nursing. Antony’s research interests are focused on the health needs of those in late life and at the end of life. He was a research team member and reviewed the final draft of this paper.

John Thurman is a Patient and Public Involvement Contributor of the DEMCOM research team. John was a research team member and involved in advising, reviewing and commenting on all aspects of the DEMCOM study drawing on his experience of supporting family members living with dementia. His views and experiences were invaluable to this study.

Ethical approval: The National Research Ethics Committee (REC) London Queen Square provided ethical approval for this study (ref: 17/LO/0996). Ethical approval was also obtained from the University of Hertfordshire Health Sciences Engineering & Technology ECDA (Protocol number: HSK/SF/UH/02728), and the University of Cambridge Ethics Committee for the School of the Humanities and Social Sciences identifiable, F020Where identifiable, references to the authors’ previous work have been removed.

ORCID iDs

Stefanie Buckner https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6820-7057

Nicole Darlington https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2505-1256

Elspeth Mathie https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5871-436X

References

- Alzheimer’s Disease International (2016). Dementia Friendly Communities: Global developments. https://www.alz.co.uk/adi/pdf/dfc-developments.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International (2017). Dementia friendly communities: Global developments. https://www.alzint.org/u/dfc-developments.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International (n.d.). Dementia friendly communities: Key principles. https://www.alz.co.uk/adi/pdf/dfc-principles.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Society (2013). Guidance for communities registering for the recognition process for dementia friendly communities. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/download/downloads/id/2885/guidance_for_communities_registering_for_the_recognition_process.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Society (2014-15). Foundation criteria for the dementia friendly Communities recognition process. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/download/downloads/id/2886/foundation_criteria_for_the_recognition_process.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Society (2018). How to become a recognised Dementia Friendly Communities. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-involved/dementia-friendly-communities/organisations/how-to-become-dementia-friendly-community [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer Europe (2019). Dementia in Europe Yearbook 2019 estimating the prevalence of dementia in Europe. file:///C:/Users/sb959/AppData/Local/Temp/FINAL05707AlzheimerEuropeyearbook2019-2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- British Standards Institution (2015). PAS 1365:2015 Code of Practice for the recognition of dementia friendly communities in England. https://www.housinglin.org.uk/_assets/Resources/Housing/OtherOrganisation/BSI_Dementia_friendly.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Buckner S. (2017). Dementia friendliness and age-friendliness. http://www.clahrc-eoe.nihr.ac.uk/about-us/people/dementia-frailty-and-end-of-life-care/demcom-national-evaluation-dementia-friendly-communities-2/ [Google Scholar]

- Buckner S., Mattocks C., Lafortune L., Rimmer M., Pope D., Bruce N. (2017). Unlocking the benefits of Age-Friendly Cities. National Health Executive [Google Scholar]

- Buckner S., Mattocks C., Rimmer M., Lafortune L. (2018). An evaluation tool for Age-Friendly and Dementia Friendly Communities. Working with Older People, 22(1), 48–58. 10.1108/WWOP-11-2017-0032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner S., Darlington N., Woodward M., Buswell M., Mathie E., Arthur A., Lafortune L., Killett A., Mayrhofer A., Thurman J., Goodman C. (2019. a). Dementia friendly communities in England: A scoping study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(8), 1235–1243. 10.1002/gps.5123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner S., Pope D., Mattocks C., Lafortune L., Dherani M., Bruce N. (2019. b). Developing Age-Friendly Cities: An evidence-based evaluation tool. Journal of Population Ageing, 12(2), 203–223. 10.1007/s12062-017-9206-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buswell M., Goodman C., Russell B., Bunn F., Mayrhofer A., Goodman E. (2017). Community engagement evidence synthesis: A final report for Alzheimer’s Society. http://researchprofiles.herts.ac.uk/portal/files/11631627/UH_Community_Engagement_Evidence_Synthesis_FINAL_Jan_2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Coyle C. (2018). Wenham connects: An age- and dementia friendly needs assessment. https://www.wenhamma.gov/WenhamPresentation10.14.2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Crampton J., Dean J., Eley R. (2012). Creating a dementia friendly York. https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/dementia-communities-york-full.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Darlington N., Arthur A., Woodward M., Buckner S., Killett A., Lafortune L., Mathie E., Mayrhofer A., Thurman J., Goodman C. (2020). A survey of the experience of living with dementia in a dementia friendly community. Dementia. 20(5), 1711–1722. 10.1177/1471301220965552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean J., Silversides K., Crampton J., Wrigley J. (2015. a). Evaluation of the Bradford Dementia Friendly Communities Programme. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/evaluation-bradford-dementia friendly-communities-programme [Google Scholar]

- Dean J., Silversides K., Crampton J., Wrigley J. (2015. b). Evaluation of the York Dementia Friendly Communities Programme. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/evaluation-york-dementia friendly-communities-programme [Google Scholar]

- Dementia Action Alliance (2020). Local DAAs. https://www.dementiaaction.org.uk/local_alliances [Google Scholar]

- Dementia Friends (2020). List of dementia friendly communities. https://www.dementiafriends.org.uk/WebArticle?page=dfc-public-listing#.Xxb27ed7lPZ [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2012). Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia: Delivering major improvements in dementia care and research by 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215101/dh_133176.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2015). Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/414344/pm-dementia2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dewing J. (2007). Participatory research: A method for process consent with persons who have dementia. Dementia, 6(1), 11–25. 10.1177/1471301207075625 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming R., Bennett K., Preece T., Phillipson L. (2017). The development and testing of the Dementia Friendly Communities Environment Assessment Tool (DFC EAT). Int Psychogeriatr, 29(2), 303–311. 10.1017/s1041610216001678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming R., Bennett K. A. (2017). Dementia Friendly Community - Environmental Assessment Tool (DFC-EAT) handbook. University of Wollongong [Google Scholar]

- Goodman C., Arthur A., Buckner S., Buswell M., Darlington N., Dickinson A., Killet A., Lafortune L., Mathie E., Mayrhofer A., Reilly P., Skedgel C., Thurman J., Woodward M. (2019). Dementia Friendly Communities: The DEMCOM Evaluation (National Institute for Health Research Policy Research Programme Project PR-R15-0116- 21003). National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). 10.18745/pb.23477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green G., Lakey L. (2013). Building dementia friendly communities: A priority for everyone. Alzheimer’s Society. http://www.actonalz.org/sites/default/files/documents/Dementia_friendly_communities_full_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Harding A. J. E., Morbey H., Ahmed F., Opdebeeck C., Lasrado R., Williamson P. R., Swarbrick C., Leroi I., Challis D., Hellstrom I., Burns A., Keady J., Reilly S. T. (2019). What is important to people living with dementia?: The ‘long-list’ of outcome items in the development of a core outcome set for use in the evaluation of non-pharmacological community-based health and social care interventions. BMC geriatrics, 19(1), 94. 10.1186/s12877-019-1103-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare P., Dean J. (2015). How can we make our cities dementia friendly? Sharing the learning from Bradford and York. Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York. https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/how-can-we-make-our-cities-dementia friendly [Google Scholar]

- Hebert C. A., Scales K. (2017). Dementia friendly initiatives: A state of the science review, Dementia, 18(5), 1858–1895. 10.1177/1471301217731433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heward M., Innes A., Cutler C., Hambidge S. (2017). Dementia friendly communities: Challenges and strategies for achieving stakeholder involvement. Health Soc Care Community, 25(3), 858–867. 10.1111/hsc.12371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imogen Blood & Associates Ltd and Innovations in Dementia (2017). Evidence review of dementia friendly communities. https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/775f77_d46a5d4647764177a5f90bb7c21c6428.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.-Y. (2017). ‘Dementia Friendly Communities’ and being dementia friendly in healthcare settings. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(2), 145–150. 10.1097/yco.0000000000000304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2018). Care needed: Improving the lives of people with dementia. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/care-needed_9789264085107-en [Google Scholar]

- Prince M., Wimo A., Guerchet M., Ali G.-C., Wu Y.-T., Prina M. (2015). World Alzheimer Report 2015: the global impact of dementia. Alzhimer’s Disease International, London. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 (2012). Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/3/enacted [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K., Bail K., Neville S. (2019). Dementia friendly community initiatives: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(11–12), 2035–2045. 10.1111/jocn.14746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp S. (2021). Logic Models vs Theories of Change. Center for Research Evaluation. https://cere.olemiss.edu/logic-models-vs-theories-of-change/ [Google Scholar]

- Turner N., Morken L. (2016). Better Together: A comparative analysis of Age-Friendly and Dementia Friendly. AARP. http://www.ageingwellinwales.com/Libraries/Documents/Better-Together---Comparison-of-Age-and-Dementia-Friendly-Communities.pdf [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2007. a). Checklist of essential features of Age-Friendly Cities. http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Age_friendly_cities_checklist.pdf [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2007. b). Global Age-Friendly Cities: A guide. http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Global_age_friendly_cities_Guide_English.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2021). Towards a dementia-inclusive society: WHO toolkit for dementia friendly initiatives (DFIs). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/343780/9789240031531-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- WHO Centre for Health Development (2015). Measuring the age-friendliness of cities: A guide to using core indicators. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/203830/1/9789241509695_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- Willis E., Semple A. C., De Waal H. (2018). Quantifying the benefits of peer support for people with dementia: A social return on investment (SROI) study. Dementia, 17(3), 266–278. 10.1177/1471301216640184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisconsin Healthy Brain Initiative (n.d.). A toolkit for building dementia friendly communities. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p01000.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Woodward M., Arthur A., Darlington N., Buckner S., Killett A., Thurman J., Buswell M., Lafortune L., Mathie E., Mayrhofer A., Goodman C. (2018). The place for dementia friendly communities in England and its relationship with epidemiological need. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(1), 67–71. 10.1002/gps.4987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Dementia Council (2020). Defining dementia friendly initiatives. https://worlddementiacouncil.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/DFIs-Paper1_V18.pdf [Google Scholar]