Abstract

Using the shuttle vector pMCO2 and the vaccinia virus wild-type WR strain, we constructed a recombinant virus expressing an 18-kDa outer membrane protein of Brucella abortus. BALB/c mice inoculated with this virus produced 18-kDa protein-specific antibodies, mostly of immunoglobulin G2a isotype, and in vitro stimulation of splenocytes from these mice with purified maltose binding protein–18-kDa protein fusion resulted in lymphocyte proliferation and gamma interferon production. However, these mice were not protected against a challenge with the virulent strain B. abortus 2308. Disruption of the 18-kDa protein's gene in vaccine strain B. abortus RB51 did not affect either the strain's protective capabilities or its in vivo attenuation characteristics. These observations suggest that the 18-kDa protein plays no role in protective immunity.

Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease caused by the members of genus Brucella, which are gram-negative, facultatively intracellular bacteria. In domestic and wild mammals, brucellosis often results in abortions and infertility. Humans usually acquire the infection by consuming contaminated dairy products or by coming in contact with an infected animal's tissues and secretions (1). In humans the disease manifests itself as a chronic infection with undulant fever and general malaise. It is generally accepted that cell-mediated immunity (CMI) is necessary for effective protection against brucellosis, although antibodies, especially against the O side chain of the lipopolysaccharide, appear to enhance resistance against infection, at least in certain host species (2, 3). Attenuated, live Brucella strains such as Brucella abortus RB51 and 19 and Brucella melitensis Rev 1 are being used as vaccines to control brucellosis in domestic animals. However, these vaccines are not suitable for humans; strains 19 and Rev 1 can cause disease in humans and there is no study ascertaining the safety of strain RB51, although human infections with this vaccine strain have not been reported. An efficient and safe vaccine is needed for the prophylaxis of human brucellosis, which is a major zoonotic health risk in many countries (8, 27) and a potential tool for biological warfare (5, 12).

Immune mechanisms operative in protection against brucellosis can be discerned by using a mouse model of vaccination and challenge infection. Development of resistance to brucellosis has been associated with the induction of a Th1-type immune response (21). However, with the exception of L7/L12 ribosomal protein and Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase, which have been shown to induce certain levels of protection (18, 19, 23), the specific proteins involved in the stimulation of a protective response have not been identified. A potential candidate for protective antigens is an 18-kDa (referred to as 19 kDa by some researchers) lipoprotein present on the surface of Brucella (14, 25). Infected mice, sheep, goats, and dogs develop antibodies to this antigen, indicating the immunological recognition of the 18-kDa protein in brucellosis of several animal species (14, 25). Humans infected with either B. abortus or B. melitensis also develop antibodies to this antigen (14). Preliminary studies carried out in our laboratory detected CMI responses to this protein in strain RB51-vaccinated mice. In order to develop an efficient recombinant vaccine for humans, we are studying the possibility of using vaccinia virus as a delivery vector for Brucella proteins of protective potential. In the present work, we constructed a recombinant vaccinia virus that can express the 18-kDa protein and characterized the specific humoral and selected CMI responses of mice vaccinated with this virus. Our studies indicated that mice vaccinated with the recombinant virus developed Th1-type immune responses to the 18-kDa protein. However, these immune responses did not lead to any level of protection against challenge infection with virulent B. abortus 2308. Further, using vaccine strain B. abortus RB51 with an interrupted gene for the 18-kDa protein, we showed that the 18-kDa protein does not appear to have any protective role in brucellosis.

Expression of B. abortus 18-kDa protein by recombinant vaccinia virus.

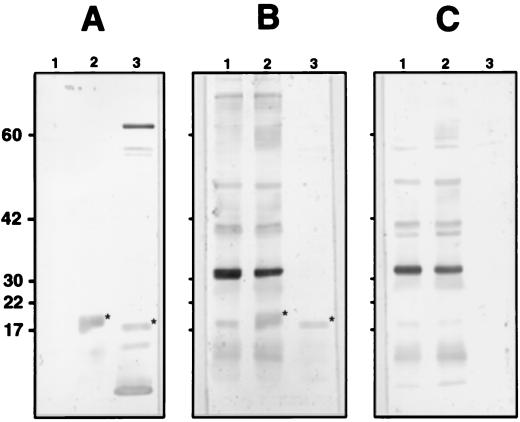

The gene for the 18-kDa protein was initially obtained from a genomic library of B. abortus 19 (unpublished data) and was subsequently sequenced (GenBank accession no. L42959). Further, the complete open reading frame of this gene (from nucleotides 282 to 833 of sequence L42959) was previously PCR amplified and cloned into plasmid pBK-CMV (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). From this plasmid, the 18-kDa antigen gene was excised with a KpnI digestion and subcloned into a vaccinia shuttle vector, pMCO2 (4). The pMCO2 plasmids containing the gene for the 18-kDa protein in the proper as well as in the reverse orientation with regard to the promoter were used in making the recombinant vaccinia viruses. The vaccinia virus recombinants were produced according to previously described methods (4, 6, 26). The recombinant vaccinia viruses containing the gene for the 18-kDa protein in proper and reverse orientation were designated v18-1 virus and v18-2 virus, respectively. The 18-kDa protein expression in the v18-1 virus- but not the v18-2 virus-infected cell culture lysates was confirmed by Western blot analysis with sera from B. abortus RB51-vaccinated mice and rabbit antiserum to the 18-kDa protein. The rabbit antiserum was prepared according to procedures described elsewhere (13). However, this protein was slightly higher in molecular weight than the native 18-kDa protein from B. abortus (Fig. 1A). This is probably because of the intact prokaryotic signal sequence of the 18-kDa protein and/or glycosylation of the expressed protein; a region containing weak homology with the consensus eukaryotic N-glycosylation site was identified in the deduced amino acid sequence of the 18-kDa protein by computer analysis.

FIG. 1.

Western blot analysis of sera (6 weeks p.i.) from mice vaccinated with B. abortus RB51 (A), v18-1 virus (B), or v18-2 virus (C). Lanes 1 and 2, antigens from lysates of HuTK− cells infected with v18-2 and v18-1 viruses, respectively. Lanes 3, antigens of B. abortus RB51. Numbers at left of panel A are approximate protein molecular masses, in kilodaltons. Asterisks in panels A and B indicate the 18-kDa antigen band.

Immune responses of mice inoculated with the recombinant vaccinia virus.

Two separate mouse experiments were performed. In each experiment, four groups of eight BALB/c female mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.) of 6 to 8 weeks of age were used. The mice of two groups were each injected with a 107-CFU median tissue culture infective dose of either v18-1 or v18-2 virus. In the first experiment an intraperitoneal route was used for inoculating animals with the vaccinia viruses, whereas in the second experiment an intradermal route was used. As a positive control, one group was injected with 108 CFU of B. abortus RB51, and as a negative control, another group was injected with saline alone. All mice were bled at 6 weeks postinoculation (p.i.) to obtain sera for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blot analyses. Three mice from each group of experiment 1 were sacrificed at 12 to 14 weeks p.i., and their splenocytes were used for in vitro CMI assays. At 7 weeks p.i., five mice from each group were challenge-infected with 2 × 104 CFU of B. abortus 2308 intraperitoneally. Two weeks after the challenge infection, the mice were killed, bacteria from their spleens were recovered, and CFU counts were determined. In conducting research using animals, the investigators adhered to guidelines set forth by a committee of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council (7a).

For use in ELISA and CMI assay, the 18-kDa protein of Brucella was expressed in Escherichia coli DH5α (Gibco BRL, Bethesda, Md.) as a fusion with maltose binding protein (MBP) by using expression vector pMalC2 (New England Biolabs Inc., Beverly, Mass.). The fusion protein (MBP–18-kDa protein) was purified by affinity chromatography on amylose resin. To achieve this, the gene for the 18-kDa protein was amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of B. abortus 2308. A primer pair consisting of one forward primer (5′ GGA TCC CAG AGC TCC CGG CTT GGT 3′) and one reverse primer (5′ AAG CTT CCC TCT TCA TCG TTT CCG 3′) was designed based on the nucleotide sequence of the 18-kDa protein gene sequence. The forward primer of the gene was selected such that the coding sequences for the signal peptide part of the antigen were not included in the amplification. PCR and cloning of the amplified product in pMalC2 were performed as previously described (28). The protein expression and purification were performed according to the manufacturer's suggested procedure. Expression of the MBP–18-kDa protein fusion was confirmed by a Western blot analysis with the 18-kDa protein-specific rabbit antiserum. Similarly purified recombinant MBP was used as a control in the lymphocyte proliferation assays.

The presence of serum immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgG1, and IgG2a isotypes with specificity to the 18-kDa protein was determined by indirect ELISA following the standard procedures (7). Purified MBP–18-kDa protein in carbonate buffer, pH 9.6, was used to coat polystyrene plates (0.5 μg/well, Nunc-Immuno plates with MaxiSorp surfaces). Isotype-specific goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase conjugates (Caltag Laboratories, San Francisco, Calif.) and TMB Microwell peroxidase substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) were used in the assay. The enzyme reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl of stop solution (0.185 M sulfuric acid), and the absorbance at 450 nm was recorded with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

Lymphocyte proliferation and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) quantification assays were performed as previously described (28). Splenocytes were cultured in the presence of 5 μg of recombinant MBP–18-kDa protein, 5 μg of MBP, 10 μg of B. abortus RB51 crude extract (28), 0.5 μg of concanavalin A, or no additives (unstimulated control). After culturing for 5 days, supernatants of the cultures were collected for quantitating IFN-γ by a sandwich ELISA, the cells were pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine/well for 18 h and harvested onto glass fiber filters, and the radioactivity was measured in a liquid scintillation counter. The assays were performed in triplicate. Results of the proliferation assay were expressed as a stimulation index (mean counts per minute from wells of test antigen/mean counts per minute of unstimulated control wells).

Mice that were inoculated with either the v18-1 virus or B. abortus RB51 developed antibody and CMI responses to the 18-kDa protein. Western blots shown in Fig. 1 demonstrate that mice inoculated with v18-1 or v18-2 virus developed IgG antibodies to the vaccinia viral proteins but only the v18-1 virus- or B. abortus RB51-inoculated mice developed antibodies to the 18-kDa protein of B. abortus. As shown in Table 1, IgG2a was the predominant isotype of antibody to the 18-kDa protein in mice inoculated with either the v18-1 virus or B. abortus RB51. However, the 18-kDa protein-specific IgG and IgG2a levels were highest in mice vaccinated with B. abortus RB51. In contrast to the mice inoculated with v18-1 virus, the mice inoculated with strain RB51 had essentially no specific IgG1 isotype antibodies to the 18-kDa protein.

TABLE 1.

ELISA detection of serum IgG, IgG2a, and IgG1 antibodies specific to the 18-kDa protein in mice at 6 weeks after inoculation with either of two recombinant vaccinia viruses or with B. abortus RB51

| Vaccination | 18-kDa antigen-specific immunoglobulin levela

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total IgG | IgG2a | IgG1 | |

| v18-1 virus | 1.158 ± 0.444 | 0.743 ± 0.245 | 0.167 ± 0.015 |

| v18-2 virus | 0.076 ± 0.063 | 0.008 ± 0.013 | 0.014 ± 0.004 |

| Strain RB51 | 1.909 ± 0.256 | 1.354 ± 0.211 | 0.003 ± 0.002 |

| Saline | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0 | 0 |

Values are mean absorbance at 450 nm ± standard deviations for three mouse serum samples.

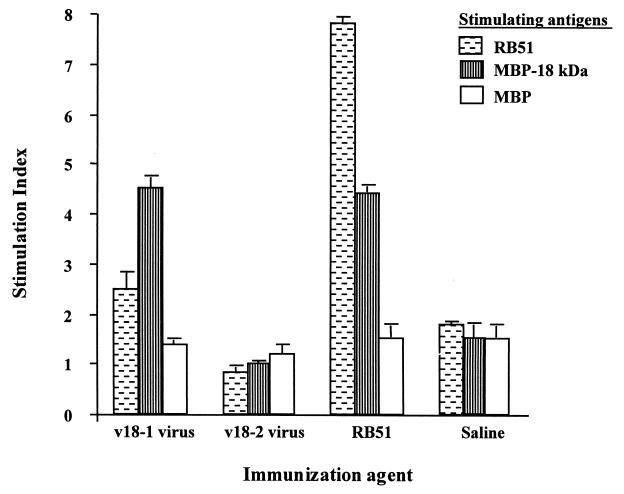

Splenocytes from mice inoculated with strain RB51 or v18-1 virus proliferated (Fig. 2) and produced IFN-γ (Table 2) upon stimulation with either MBP–18-kDa protein or strain RB51 antigen extract. Splenocytes from the control mice (v18-2 virus or saline injected) did not respond to stimulation with either strain RB51 antigen extract or MBP–18-kDa protein. Splenocytes from mice inoculated with v18-1 virus or strain RB51 responded with similar levels of IFN-γ production upon stimulation with MBP–18-kDa protein. However, when stimulated with strain RB51 antigen extract, splenocytes from strain RB51-inoculated mice produced much higher levels of IFN-γ than those from the v18-1 virus-inoculated mice. A similar tendency was also observed in the lymphocyte proliferation assay.

FIG. 2.

In vitro proliferative responses of splenocytes from vaccinated and control mice. The assays were set up in triplicate, and the cells were either left unstimulated (media alone) or stimulated with antigens as described in Materials and Methods. Results are mean stimulation indices ± standard deviations (error bars) (n = 3).

TABLE 2.

IFN-γ production by splenocytes of inoculated mice after in vitro stimulation with specific antigens or mitogen

| Antigen | IFN-γ concn (ng/ml)a in culture supernatant of splenocytes from mice vaccinated with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| v18-1 virus | v18-2 virus | RB51 | Saline | |

| Media | —b | — | — | — |

| Concanavalin A | 26 ± 6.2 | 28 ± 4.3 | 24 ± 7.4 | 24 ± 4.0 |

| RB51 | 1.78 ± 0.81 | — | 18 ± 6.0 | — |

| MBP–18-kDa | 0.3 ± 0.13 | — | 0.16 ± 0.1 | — |

| MBP | — | — | — | — |

Values are means ± standard deviations for three experiments.

—, below lower detection limit (<100 pg/ml).

No difference in challenge strain B. abortus 2308 counts between spleens from mice inoculated with saline, v18-1 virus, or v18-2 virus was observed (data not shown). This indicates that the detected humoral and cell-mediated immune responses against the 18-kDa protein were unable to protect mice against the challenge infection. As expected, strain RB51-vaccinated mice were protected significantly against challenge infection (20).

Effect of disruption of the gene for the 18-kDa protein on protective capabilities of strain RB51.

Since the mice inoculated with v18-1 virus were not protected against the challenge infection, we verified the lack of a potential protective role for the 18-kDa protein in strain RB51. We disrupted the gene encoding the 18-kDa protein by inserting a kanamycin cassette. This was achieved by cloning a 994-bp DNA fragment containing the gene for the 18-kDa protein (GenBank accession no. L42959) in EcoRI and NcoI sites of pRSETC (Invitrogen) to generate pRS18. A kanamycin cassette obtained from pUC4K (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) was inserted into the SacI site present within the open reading frame (72 bp from the start codon) of the 18-kDa protein gene to create pRS18Δkan. The pRS18Δkan plasmid was electroporated into B. abortus RB51 (16) to replace the native gene by homologous recombination. The kanamycin-resistant colonies were screened for the presence of the kanamycin cassette and the disruption of the gene for the 18-kDa protein by Southern blot hybridization according to methods previously described (reference 15 and data not shown). The disruption mutant was designated RB51Δ18kDa. To determine the infectivity and protectivity characteristics of strain RB51Δ18kDa and to compare them with those of strain RB51, experiments with mice were performed as previously described (17, 20). Strain RB51Δ18kDa did not express the 18-kDa protein, as determined by the Western blot analysis (data not shown). Our studies also revealed that the ability of strain RB51Δ18kDa to survive within mice was similar to that of strain RB51 (data not shown), indicating that the disruption had no influence on the in vivo survival of this vaccine strain. Mice inoculated with strain RB51Δ18kDa produced neither antibody nor CMI responses to the 18-kDa protein, yet they were protected to the same extent as the strain RB51-inoculated mice (data not shown).

Inoculation of mice with live v18-1 virus resulted in 18-kDa protein-specific antibodies predominantly of subisotype IgG2a, suggesting the induction of a Th1 type of immune response (22). Furthermore, the proliferation and production of IFN-γ by splenocytes of these mice upon in vitro stimulation with the specific antigen demonstrated a Th1 response to the 18-kDa protein. However, these immune responses did not result in protection against a challenge infection with virulent B. abortus 2308. We do not expect the 18-kDa protein-specific antibodies to have a protective role, since passive transfer of strain RB51-induced antibodies, which include antibodies to the 18-kDa protein, did not confer protection to challenge with B. abortus 2308 (11). The lack of protection could be due to inappropriate posttranslational processing of the vaccinia virus-expressed 18-kDa protein resulting in an altered antigenicity or loss of crucial CMI-inducing protective epitopes. As previously mentioned, the 18-kDa protein in Brucella appears to be a lipoprotein (25); this lipid modification would not have occurred in the vaccinia virus-expressed 18-kDa protein. Also, any glycosylation of the 18-kDa protein might have affected the antigen processing by the host antigen-presenting cells. Nevertheless, disruption of the 18-kDa protein gene in vaccine strain B. abortus RB51 had no influence on the strain's ability to induce protection in vaccinated mice. Since strain RB51Δ18kDa was constructed by inserting a kanamycin cassette at 72 bp (24 codons) downstream of the start site of the gene for the 18-kDa protein, this mutant is capable of synthesizing a peptide consisting of the first 24 amino acids of the 18-kDa protein. The first 20 of these 24 amino acids form the signal peptide sequence of the 18-kDa protein (14, 25). In Brucella, this signal peptide is cleaved off and the rest of the polypeptide is subjected to lipid modification (25). Therefore, there is a possibility that this signal peptide contains crucial protective epitopes and we failed to detect this immune response in mice inoculated with our disruption mutant since our recombinant 18-kDa fusion protein also lacked these 24 amino acids. However, ongoing studies in our laboratory indicate that overexpression of the 18-kDa protein with its signal sequence in strain RB51 did not enhance its protective ability, while overexpression of known protective antigens did (Vemulapalli et al., unpublished results). Taken together, it appears that the 18-kDa outer membrane protein of B. abortus is not involved in mediating protective immunity, although it is able to induce low levels of IFN-γ production from specific immune lymphocytes. Production of IFN-γ by specific antigen stimulation of lymphocytes is considered to be important in protection, since it is able to activate macrophages which are able to contain Brucella replication (29, 30).

Based on the results of this study and in accordance with other published findings (9, 10, 24), it appears that many Brucella proteins to which infected or vaccinated animals develop appropriate immune responses may not play a crucial role in host-acquired protective immune mechanisms to brucellosis. Until a reliable in vitro assay that correlates positively with the protective potential of a Brucella protein is developed, the present trial-and-error strategy is the only means available to verify the protective role of a Brucella protein antigen.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research, Development, Acquisition and Logistics Command (Prov.) under contract no. DAMD 17-94-C-4042.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acha P, Szyfres B. Zoonoses and communicable diseases common to man and animals. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 1980. pp. 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araya L N, Elzer P H, Rowe G E, Enright F M, Winter A J. Temporal development of protective cell-mediated and humoral immunity in BALB/c mice infected with Brucella abortus. J Immunol. 1989;143:3330–3337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araya L N, Winter A J. Comparative protection of mice against virulent and attenuated strains of Brucella abortus by passive transfer of immune T cells or serum. Infect Immun. 1990;58:254–256. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.254-256.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll M W, Moss B. E. coli β-glucuronidase (GUS) as a marker for recombinant vaccinia viruses. BioTechniques. 1995;19:352–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carus W S. Biological warfare threats in perspective. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1998;24:149–155. doi: 10.1080/10408419891294299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakrabarti S, Brechling K, Moss B. Vaccinia virus expression vector: coexpression of β-galactosidase provides visual screening of recombinant virus plaques. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:3403–3409. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coligan J E, Kruisbeek A M, Marulies D H, Shevach E M, Strober W, editors. Current protocols in immunology. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1991. pp. 8.4.1–8.10.6. [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Institutes of Health publication no. 86–23. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corbel M J. Brucellosis: an overview. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:213–221. doi: 10.3201/eid0302.970219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denoel P A, Vo T K, Weynants V E, Tibor A, Gilson D, Zygment M S, Limet J N, Letesson J J. Identification of the major T-cell antigens present in the Brucella melitensis B115 protein preparation, Brucellergene OCB. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:801–806. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-9-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guilloteau L A, Laroucau K, Vizcaino N, Jacques I, Dubray G. Immunogenicity of recombinant Escherichia coli expressing the omp31 gene of Brucella melitensis in BALB/c mice. Vaccine. 1999;17:353–361. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00205-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jimenez de Bagues M P, Elzer P H, Jones S M, Blasco J M, Enright F M, Schurig G G, Winter A J. Vaccination with Brucella abortus rough mutant RB51 protects BALB/c mice against virulent strains of Brucella abortus, Brucella melitensis, and Brucella ovis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4990–4996. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4990-4996.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufmann A F, Meltzer M I, Schmid G P. The economic impact of a bioterrorist attack: are prevention and postattack intervention programs justifiable? Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:83–94. doi: 10.3201/eid0302.970201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knudsen K A. Proteins transferred to nitrocellulose for use as immunogens. Anal Biochem. 1985;147:285–288. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovach M E, Elzer P H, Robertson G T, Chirhart-Gilleland R L, Christensen M A, Peterson K M, Roop R M., II Cloning and nucleotide sequence analysis of a Brucella abortus gene encoding an 18 kDa immunoreactive protein. Microb Pathog. 1997;22:241–246. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Latimer E, Simmers J, Sriranganathan N, Roop II R M, Schurig G G, Boyle S M. Brucella abortus deficient in copper/zinc superoxide dismutase is virulent in BALB/c mice. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McQuiston J R, Schurig G G, Sriranganathan N, Boyle S M. Transformation of Brucella species with suicide and broad host-range plasmids. Methods Mol Biol. 1995;47:143–148. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-310-4:143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McQuiston J R, Vemulapalli R, Inzana T J, Schurig G G, Sriranganathan N, Fritzinger D, Hadfield T L, Warren R A, Snellings N, Hoover D, Halling S M, Boyle S M. Genetic characterization of a Tn5-disrupted glycosyltransferase gene homolog in Brucella abortus and its effect on lipopolysaccharide composition and virulence. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3830–3835. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3830-3835.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliveira S C, Splitter G A. Immunization of mice with recombinant L7/L12 ribosomal protein confers protection against Brucella abortus infection. Vaccine. 1996;14:959–962. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(96)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onate A A, Vemulapalli R, Andrews E, Schurig G G, Boyle S, Folch H. Vaccination with live Escherichia coli expressing Brucella abortus Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase protects mice against virulent B. abortus. Infect Immun. 1999;67:986–988. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.986-988.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schurig G G, Roop R M, Bagchi T, Boyle S M, Buhrman D, Sriranganathan N. Biological properties of RB51: a stable rough strain of Brucella abortus. Vet Microbiol. 1991;28:171–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90091-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Splitter G, Oliveira S, Carey M, Miller C, Ko J, Covert J. T lymphocyte mediated protection against facultative intracellular bacteria. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;54:309–319. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(96)05703-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens T L, Bossie A, Sanders V M, Fernandez R, Coffman R L, Mosmann T R, Vitetta E S. Regulation of antibody isotype secretion by subsets of antigen-specific helper T cells. Nature. 1988;334:255–258. doi: 10.1038/334255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabatabai L B, Pugh G W., Jr Modulation of immune responses in Balb/c mice vaccinated with Brucella abortus Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase synthetic peptide vaccine. Vaccine. 1994;12:919–924. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tibor A, Jacques I, Guilloteau L, Verger J M, Grayon M, Wansard V, Letesson J J. Effect of P39 gene deletion in live Brucella vaccine strains on residual virulence and protective activity in mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5561–5564. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5561-5564.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tibor A, Saman E, de Wergifosse P, Cloeckaert A, Limet J N, Letesson J J. Molecular characterization, occurrence, and immunogenicity in infected sheep and cattle of two outer membrane proteins of Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:100–107. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.100-107.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toth T E, Cobb J A, Boyle S M, Roop R M, Schurig G G. Selective humoral immune response of Balb/C mice to Brucella abortus proteins expressed by vaccinia virus recombinants. Vet Microbiol. 1995;45:171–183. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00047-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trujillo I Z, Zavala A N, Caceres J G, Miranda C Q. Brucellosis. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1994;8:225–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vemulapalli R, Duncan A J, Boyle S M, Sriranganathan N, Toth T E, Schurig G G. Cloning and sequencing of yajC and secD homologs of Brucella abortus and demonstration of immune responses to YajC in mice vaccinated with B. abortus RB51. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5684–5691. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5684-5691.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhan Y, Cheers C. Endogenous gamma interferon mediates resistance to Brucella abortus infection. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4899–4901. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4899-4901.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhan Y, Yang J, Cheers C. Cytokine response of T-cell subsets from Brucella abortus-infected mice to soluble Brucella proteins. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2841–2847. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2841-2847.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]