Summary

The folic acid cycle mediates the transfer of one-carbon (1C) units to support nucleotide biosynthesis. While the importance of serine as a mitochondrial and cytosolic donor of folate-mediated 1C units in cancer cells has been thoroughly investigated, a potential role of glycine oxidation remains unclear. We developed an approach for quantifying mitochondrial glycine cleavage system (GCS) flux by combining stable and radioactive isotope tracing with computational flux decomposition. We find high GCS flux in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), supporting nucleotide biosynthesis. Surprisingly, other than supplying 1C units, we found that GCS is important for maintaining protein lipoylation and mitochondrial activity. Genetic silencing of glycine decarboxylase inhibits the lipoylation and activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase and impairs tumor growth, suggesting a novel drug target for HCC. Considering the physiological role of liver glycine cleavage, our results support the notion that tissue of origin plays an important role in tumor-specific metabolic rewiring.

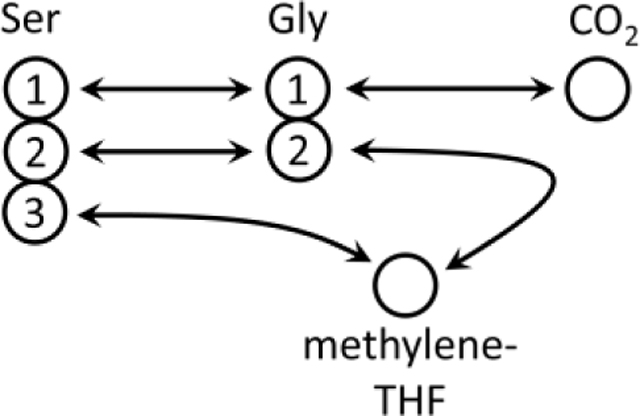

Serine catabolism has been identified as a major source of 1C units in tumors (Ducker et al., 2016). Mitochondrial serine catabolism through SHMT2 was shown to be a major producer of 1C units for nucleotide biosynthesis (Ducker et al., 2016), and supporting mitochondrial translation via tRNA methylation (Morscher et al., 2018) and the synthesis of formylmethionine (Minton et al., 2018). Recent work highlighted the important role of cytosolic serine catabolism for biosynthesis in various cancers depending on their capacity to retain intracellular folates under physiological conditions (Lee et al., 2021). Upregulation of de novo serine biosynthesis via genomic amplification of PHGDH (encoding phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase) was found to support breast and melanoma tumor growth (Locasale et al., 2011; Mullarky et al., 2011; Pollari et al., 2011; Possemato et al., 2011). Serine starvation was shown to reduce tumor growth in multiple mouse models of cancer (Vincent et al., 2017). Glycine catabolism in mitochondria through GCS produces 1C units in the form of 5,10-methylene-THF, releasing the second carbon atom of glycine as CO2 (Kikuchi et al., 2008). A role of GCS in tumors has been scarcely studied: GCS was proposed to have an oncogenic role in tumor-initiating lung cancer cells, modulating glycolysis and nucleotide metabolism (Zhang et al., 2012). In glioblastoma, GCS was suggested to be essential to prevent the accumulation of toxic aldehydes produced by glycine metabolism (Kim et al., 2015).

Results and Discussion

Hepatocellular carcinoma has high expression and metabolic flux of GCS

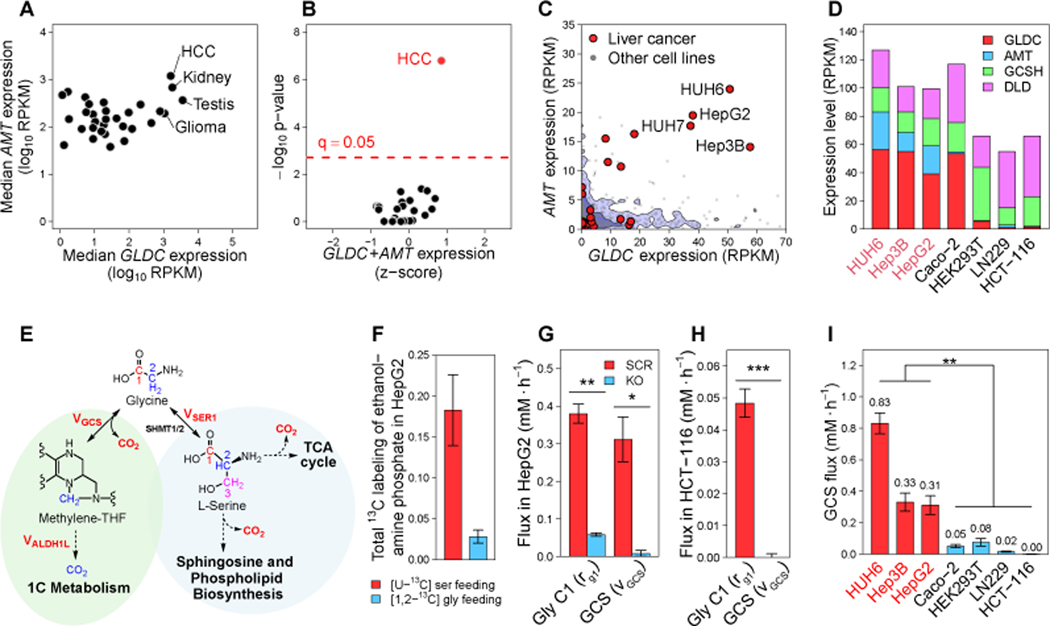

To systematically identify tumors with high GCS activity, we analyzed the expression level of the four genes coding for GCS subunits (GLDC, AMT, GCSH, and DLD) in The Cancer Genome Atlas (Hutter and Zenklusen, 2018). We found markedly high expression of two subunits of GCS, GLDC and AMT, in hepatocellular carcinoma and renal cancer (Figure 1A). High expression of GLDC in these cancers is consistent with its high expression in healthy liver and kidney based on GTEx data (GTEx Consortium, 2020) (Figure S1A). Accordingly, we find significantly high expression of GCS genes in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines in the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (adjusted p-value < 10−6; Figure 1B), with exceptionally high expression of GLDC and AMT in HUH6, Hep3B, and HepG2 (Figures 1B, 1C, and 1D).

Figure 1. Hepatocellular carcinoma has high expression and activity of mitochondrial glycine cleavage system (GCS).

(A) Median expression of GLDC (x-axis) and AMT (y-axis) across tumors in TCGA data (Hutter and Zenklusen, 2018).

(B) Mean expression of GLDC and AMT across CCLE cancer cell lines (Barretina et al., 2012) (z-score normalized; x-axis), and significance p-value for mean GCS expression (sum of squared z-scores against χ2 distribution; y-axis). Significance FDR threshold 0.05 (Bonferroni) is shown as a dashed line.

(C) Expression of GLDC (x-axis) and AMT (y-axis) across CCLE cell lines.

(D) The expression level of GCS genes in a panel of HCC (red labels) and non-HCC (black labels) cell lines that are analyzed here (Barretina et al., 2012).

(E) Glycine carbon-1 oxidation pathways, through GCS and via conversion to serine.

(F) Fraction of M+2 ethanolamine phosphate in HepG2 fed with [U-13C] serine or [1,2-13C] glycine for 24 h.

(G) Total measured glycine C1 oxidation flux (rG1, n = 3) versus the GCS flux (after decomposition; STAR Methods) in CRISPR-Cas9 GLDC knockout HepG2 (KO) and the scrambled gRNA (SCR) control. (See also Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.)

(H) Total measured glycine C1 oxidation flux (rG1, n = 3) versus the GCS flux in HCT-116. (See also Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.)

(I) GCS flux (vGCS) in a panel of HCC (red labels) and non-HCC (black labels) cell lines. (See also Supplementary Table 2)

Data on panels F, G, H, and I are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by two-sided Welch’s t-test.

Testing whether HCC cell lines have induced glycine cleavage flux is technically challenging: The common approach for probing GCS flux involves feeding 14C-glycine and detecting 14CO2 release rate (Kikuchi et al., 2008), though this does not account for glycine oxidation through alternative pathways. Specifically, glycine is used for serine biosynthesis through serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT1/2), while serine gets oxidized to CO2 via a variety of pathways: e.g., serine C-palmitoyltransferase in sphingolipid biosynthesis (Hanada, 2003) and phosphatidylserine decarboxylation in phosphatidylethanolamine de novo biosynthesis (Di Bartolomeo et al., 2017) (Figure 1E). Indeed, feeding HepG2 cells with [1,2-13C] glycine or with [U-13C] serine, we detect substantial M+2 labeling of ethanolamine phosphate (Figure 1F); while feeding HEK293T with these isotopic tracers also shows sphinganine labeling (Figures S1B-C). Isotope exchange through de novo serine biosynthesis also leads to the labeling of glycolytic metabolites from 13C-serine, with labeled pyruvate then oxidized through TCA cycle (Figure S1D).

We developed a novel method for quantifying GCS flux by feeding [1,2-14C] serine, [1-14C] glycine, and [2-14C] glycine and computational decomposition of measured 14CO2 release rates (STAR Methods; Figures S1E-K); also relying on [U-13C] serine and [1,2-13C] glycine tracing to assess the interconversion between serine and glycine isotopic labeling. Applied for HepG2, we infer a GCS flux of ~0.3mM/h. As a validation, we performed CRISPR-Cas9 KO of GLDC in HepG2 and reapplied this method, finding that GCS flux significantly drops below the limit of detection (Figures 1G and S1L-M). Notably, substantial release of 14CO2 is still observed upon GLDC KO, due to interconversion of the isotopic glycine to serine which is then oxidized (Figure 1G). Similarly, feeding HCT-116 with [1-14C] glycine leads to the release of 14CO2, while after accounting for serine oxidation, we find no GCS flux (Figure 1H; Tables S1-2). Applying this method for a panel of cell lines reveals GCS flux of 0.3–0.8 mM/h in HCC cells, which is significantly higher than in several non-HCC cell lines tested (t-test p-value < 0.01; Figure 1I). The high GCS flux is associated with glycine consumption from media in the HCC cell lines, while glycine secretion (or no glycine uptake) was found in the non-HCC cell lines (Figure S1N). Consistently, GLDC KO HepG2 cells drastically lower glycine uptake, supporting GCS reliance on media glycine supply (Figure S1N).

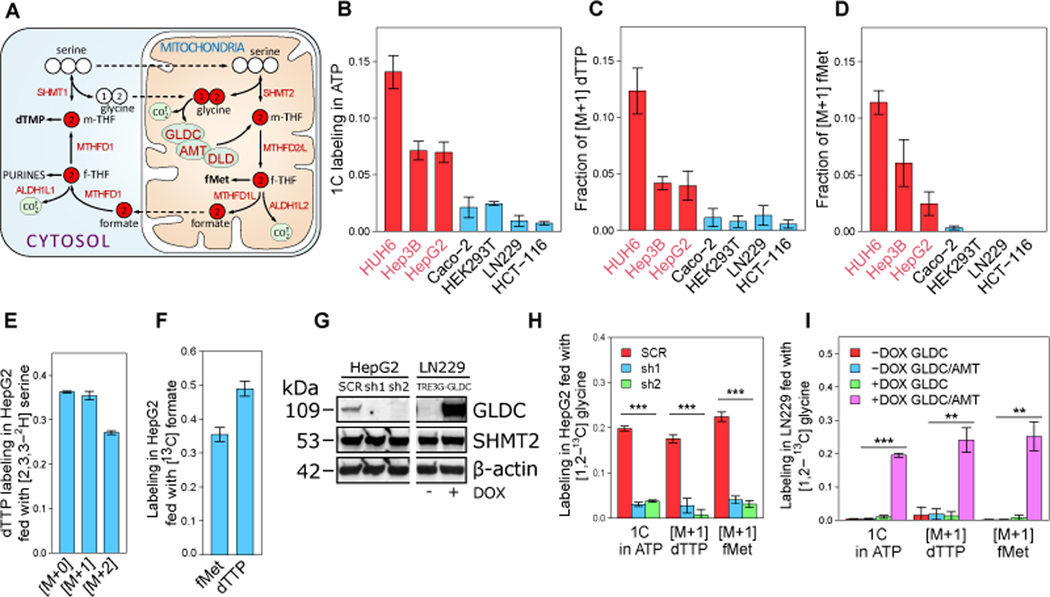

Glycine-derived 1C units support purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis in HCC

Feeding cell lines with [1,2-13C] glycine shows an appreciable contribution of GCS for de novo purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis in HCC, with higher fractional isotopic labeling of folate-derived 1C units in ATP and dTTP in HCC versus non-HCC cell lines (Figures 2A-C; STAR Methods). Specifically, in HepG2, we find that ~7% of the 1C units in ATP originate from glycine, suggesting that GCS-derived 1C flux towards purine biosynthesis is ~0.16 mM/h (considering an estimation of cell proliferation-associated demand for 1C units for purine biosynthesis; STAR Methods). Hence, considering our measured GCS flux of ~0.3 mM/h in HepG2, purine biosynthesis is a major target for 1C units produced by GCS. The contribution of GCS flux to biosynthesis is mediated by shuttling of mitochondrial formate to cytosol, similarly to mitochondrial serine-derived 1C units (Ducker et al., 2016), as supported by [1,2-13C] glycine feeding, which leads to higher labeling of formylmethionine (synthesized from mitochondrial 10-formyl-THF) in HCC cell lines (Figure 2D). Feeding of HepG2 with [2,3,3-2H] serine shows substantial M+1 dTTP, suggesting shuttling of mitochondrial serine and glycine derived 1C units to cytosol (Ducker et al., 2016) (Figure 2E). Furthermore, fed 13C-formate is readily utilized for purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis, producing cytosolic 10-formyl-THF via MTHFD1, as well as mitochondrial 10-formyl-THF (synthesizing formylmethionine; Figure 2F). GLDC shRNA knockdown (KD) shows a significant drop in nucleotide and formylmethionine labeling from fed [1,2-13C] glycine (Figures 2G-H), supporting a role of GCS in producing 1C units for biosynthesis (as also observed in CRISPR-Cas9 GLDC KO cells fed with [1,2-13C] glycine). Conversely, overexpressing GLDC and AMT in LN229 (having low basal expression of these genes; Figure 1D) shows a major induction in the contribution of GCS flux to purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis (Figures 2G and 2I). Overall, our results show, for the first time, the involvement of GCS flux in purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis in HCC, in which all GCS subunits are highly expressed.

Figure 2. Glycine-derived 1C units support purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis in HCC.

(A) Schematics of the cytosolic and mitochondrial folic acid cycles.

(B), (C), and (D) Fractional isotopic labeling of one-carbon units in ATP (B), in dTTP (C) and in N-formylmethionine (fMet) (D) in cells fed with [1,2-13C] glycine (normalized by the fractional labeling of intracellular M+2 glycine).

(E) Fractional isotopic labeling of dTTP in HepG2 cells fed with [2,3,3-2H] serine.

(F) Fractional labeling of fMet and dTTP in HepG2 cells fed with 13C formate.

(G) Western blot for GLDC, SHMT2, and β-actin in shRNA GLDC knockdown HepG2 cells (sh1 and sh2) and the scrambled shRNA (SCR) control, and in LN229 with doxycycline (DOX)-inducible expression of GLDC and AMT, with and without DOX treatment (n = 1).

(H) Fractional isotopic labeling of one-carbon units in ATP, dTTP, and fMet in HepG2 with GLDC knockdown or expressing scrambled shRNA fed with [1,2-13C] glycine.

(I) Labeling in LN229 with DOX-inducible expression of GLDC with and without DOX fed with [1,2-13C] glycine.

Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by two-sided Welch’s t-test.

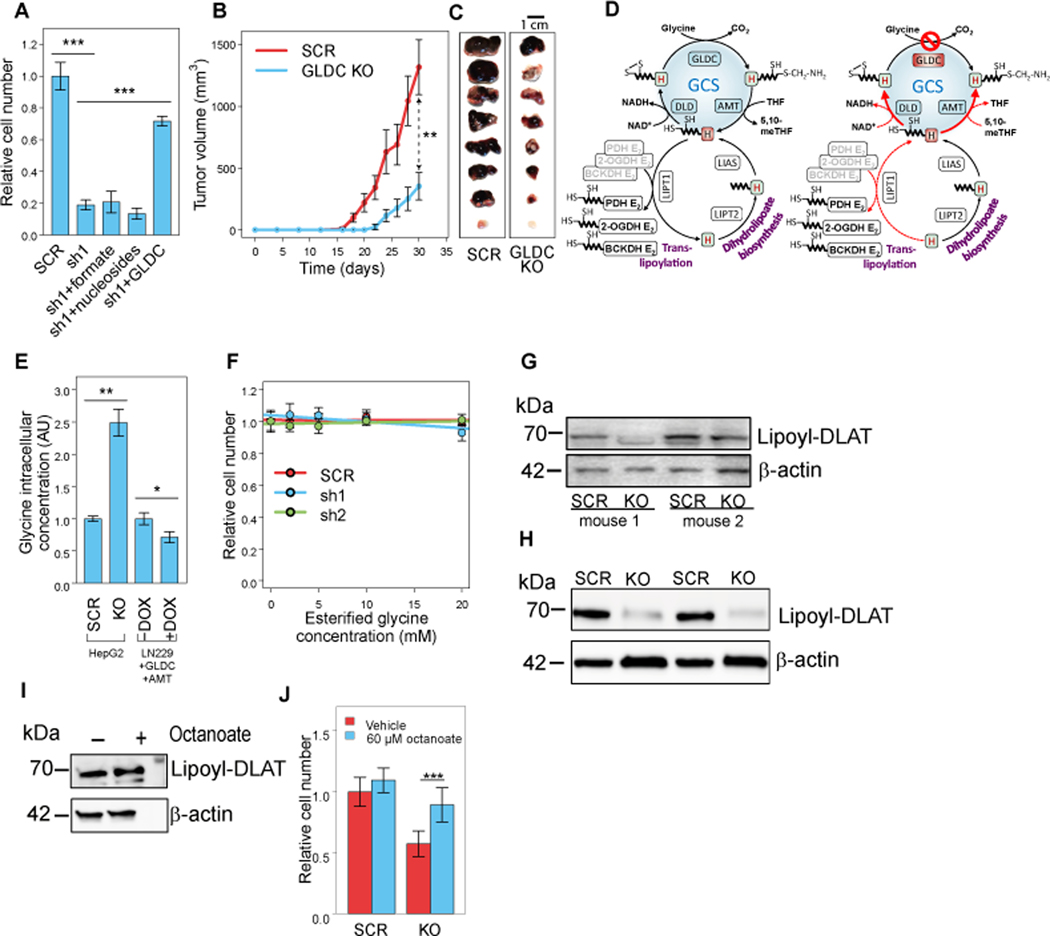

GLDC silencing inhibits HCC cell proliferation and xenograft tumor growth

GLDC silencing significantly inhibits cell proliferation in HepG2 (Figures 3A and S2A) and in Hep3B and HUH6 (Figures S2B-D, S2G). The on-target effect of GLDC silencing was validated by re-expressing GLDC in HepG2 knockdown cells, which rescued cell proliferation (Figure 3A). To evaluate the importance of GLDC in vivo, GLDC WT and KO HepG2 cells were injected into the hind flanks of NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid/NCrHsd mice. We found a significantly slower growth of the GLDC KO tumors, with ~4-fold smaller tumor volume, four weeks after tumor cell grafting (Figures 3B and 3C; p-value < 0.01). Tumors derived from HepG2 with doxycycline-inducible GLDC knockdown also demonstrate slower growth with doxycycline treatment in comparison to tumors without doxycycline treatment or tumors expressing doxycycline-induced scrambled shRNA (Figure S2J). Similarly, we detect slower growth of xenograft tumors with GLDC knockdown Hep3B and HUH6 cells (Figures S2E-F and S2H-I).

Figure 3. GLDC silencing inhibits PDH lipoylation, impairing HepG2 cell proliferation and xenograft tumor growth.

(A) Growth (4 days) of shRNA GLDC knockdown HepG2 cells (sh1), a scrambled shRNA (SCR) control, shRNA GLDC knockdown ectopically expressing GLDC, and shRNA GLDC knockdown supplemented with 1 mM sodium formate or 80 mg/l nucleoside mix. Data are mean ± SE (n = 7). (See also Figure S2A.)

(B) Growth of murine tumor xenografts with CRISPR-Cas9 GLDC KO HepG2 versus a scrambled gRNA (SCR) control. Two-sided t-test was applied to the last timepoint (p < 0.01). Data are mean ± SE (n = 8).

(C) Excised tumor xenografts.

(D) Schematics of GCS and its H-subunit mediating the transfer of dihydrolipoyl moiety to other mitochondrial lipoic acid dependent complexes in unperturbed (left) and GLDC-silenced (right) cells.

(E) Intracellular glycine level in GLDC KO versus SCR HepG2; and in LN229 with/without DOX. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3).

(F) Growth (4 days; change in cell number relative to the control without esterified glycine) of shRNA GLDC KD and SCR (y-axis) when feeding with increasing concentrations of esterified glycine (x-axis). Data are mean ± SD (n = 8).

(G) Lipoylation of DLAT in xenograft tumors with scrambled gRNA expressing (SCR) and GLDC knockout HepG2 cells (two biological replicates).

(H) Lipoylation of DLAT in scrambled gRNA expressing (SCR) and GLDC knockout HepG2 cells grown in tissue culture (two biological replicates).

(I) Effect of feeding CRISPR-Cas9 GLDC KO HepG2 cells with 15 μM octanoate for 48 hours on DLAT lipoylation (n = 1).

(J) Growth (7 days; change in cell number relative to the control with α-cyclodextrin only) of CRISPR-Cas9 GLDC KO HepG2 versus a scrambled gRNA (SCR) control, when feeding with 60 μM octanoate. Data are mean ± SD (n = 8).

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by two-sided Welch’s t-test.

Considering the observed contribution of glycine cleavage to purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis in HepG2, we tested whether feeding cells with formate as an alternative source for 1C units rescues growth of GLDC KD. We found that while HepG2 rapidly consumed and utilized formate for biosynthesis (Figure 2D), formate (or nucleoside) feeding does not rescue GLDC KD cell growth (Figure 3A), suggesting a different role of GCS other than supplying 1C units for purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis. Consistently, GLDC KD cells do not show a drop of intracellular purine and pyrimidine levels (Figure S3A).

Investigating the mechanism of GLDC importance for cell proliferation in HepG2, we raised several hypotheses related to potential harmful downstream cellular effects of perturbing the concentration of GCS reactants (Figure 3D).

First, we hypothesized that the loss of GLDC would lead to the production of toxic aldehyde due to accumulation of intracellular glycine (Kim et al., 2015). We found that GLDC knockout indeed leads to a significant increase in intracellular glycine levels; and conversely, GLDC overexpression in LN229 lowered intracellular glycine levels (Figure 3E). However, feeding esterified glycine, which readily diffuses through the cell membrane (and hence increase the intracellular glycine levels; Figure S3B), had no growth inhibitory effect in HepG2 WT or GLDC KD cells (Figure 3F), suggesting that GLDC KD growth inhibition is not due to glycine accumulation or associated downstream effects.

Second, GLDC knockout is expected to lead to a drop in the concentration of its product methylene-THF, which was recently shown to be essential for mitochondrial tRNA methylation (when knocking out SHMT2) (Morscher et al., 2018). However, we find no effect of GLDC knockout on the concentration of 5-taurinomethyluridine (Figure S3C); supposedly, as mitochondrial methylene-THF was still produced from serine catabolism via SHMT2 (as supported by [2,3,3-2H] serine tracing in GLDC KO cells; Figure S3D).

Third, GLDC knockout is expected to lead to depletion of dihydrolipoamide containing H-protein: either oxidized through DLD to form lipoamide-containing H-protein (accumulated due to GLDC knockout); or used as substrate for reverse flux through AMT to produce aminomethyllipoamidyl H-protein (Kikuchi et al., 2008). Considering that dihydrolipoamide-containing H-protein mediates the transfer of dihydrolipoyl moiety to other mitochondrial lipoic acid-dependent complexes (to the E2 subunits of 2-oxoacid dehydrogenases) (Cao et al., 2018), we hypothesize that its depletion due to GLDC knockout could impair protein lipoylation (Figure 3D). Indeed, western blot analysis confirmed a marked drop in the concentration of lipoylated E2 subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (DLAT) in GLDC KO versus control HepG2 SCR both in cultured cells and in tumor xenografts (Figures 3G-H; control 4-HNE treatment on Figure S3E); as well as in GLDC silenced Hep3B and HUH6 cells and tumors (Figures S3F-K). Conversely, feeding with a precursor of lipoic acid biosynthesis, octanoic acid, led to a moderate increase in DLAT lipoylation in GLDC KO HepG2 cells (Figures 3I, S4A-D) while significantly increasing the proliferation rate of GLDC KO and not in control cells (Figure 3J). Notably, mammalian cells do not possess lipoate salvage activity and are hence unable to utilize fed lipoate for protein lipoylation (Cao et al., 2018; Solmonson and DeBerardinis, 2018) (Figure S4A). As a further confirmation of the role of GLDC in protein lipoylation, we found that glycine feeding significantly increases DLAT lipoylation (Figures S4E-F) and that non-HCC cells with markedly lower GLDC levels also have lower DLAT lipoylation (Figure S4G).

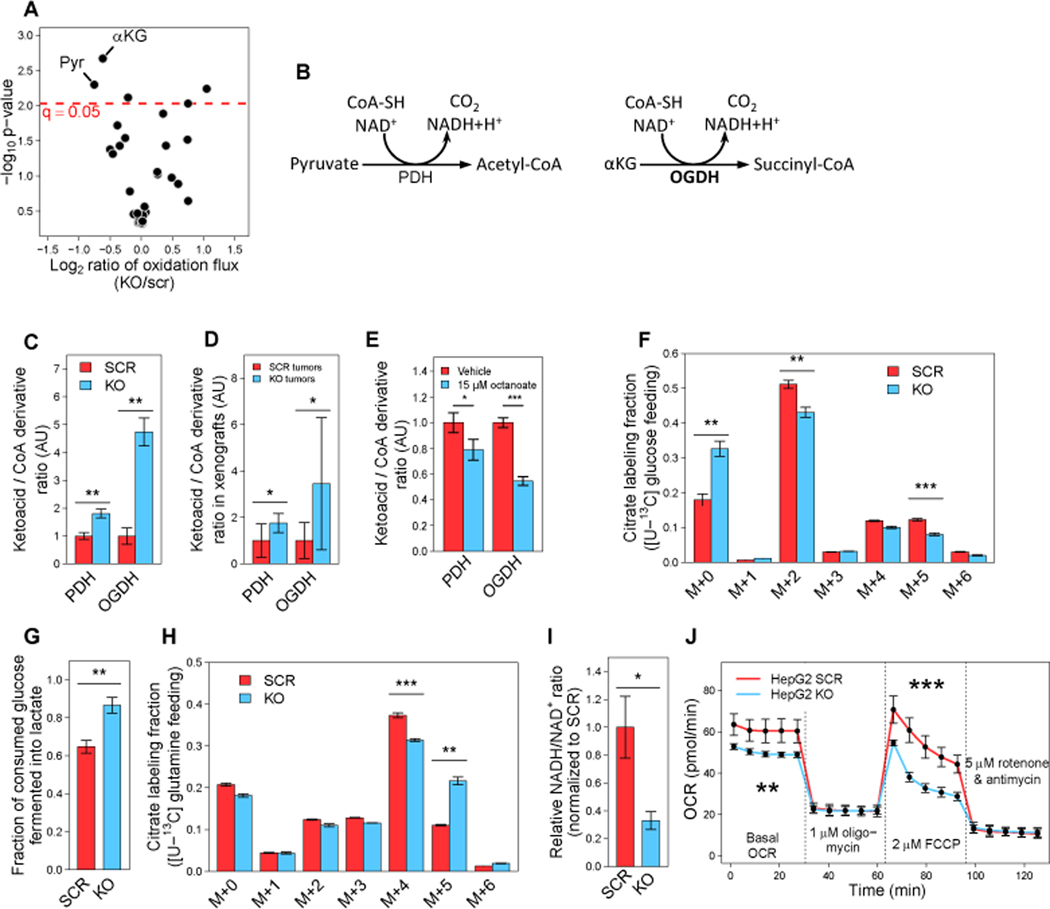

GLDC silencing affects lipoic acid-dependent complexes and impairs mitochondrial metabolism

To investigate how GLDC-induced drop in protein lipoylation affects mitochondrial metabolism, we performed a phenotypic assay, measuring the capacity of mitochondria to oxidize a variety of metabolic substrates (STAR Methods). We found that GLDC KO cells have a significantly lower capacity to specifically oxidize pyruvate and α-ketoglutarate, the substrates of the lipoic acid-dependent complexes PDH (pyruvate dehydrogenase) and OGDH (oxoglutarate dehydrogenase), respectively (Figure 4A). For both PDH and OGDH, we find a significant increase in the substrate-to-product ratio (ketoacids to corresponding CoA derivatives) upon GLDC knockout in cultured HepG2 cells (Figures 4B and 4C); pyruvate to acetyl-CoA ratio increase by 80% and α-ketoglutarate to succinyl-CoA ratio increased by 370% (p-value < 0.01). Similar metabolic changes are observed in metabolomics of GLDC KO HepG2 xenografts (Figure 4D; p-values < 0.05), doxycycline-inducible GLDC KD HepG2 xenografts (Figure S4H; p-value < 0.05), and GLDC KD Hep3B and HUH6 xenografts (Figures S4I-J). Octanoate supplementation in vitro partially rescues PDH and OGDH activity, as evident by a significant decrease in ketoacids to corresponding CoA derivatives ratios in GLDC knockout cells (Figure 4E). A drop in PDH flux upon GLDC KO is further supported by feeding cells with [U-13C] glucose, showing a significant drop in M+2 citrate (Figure 4F); and by a significant increase in the fraction of consumed glucose that is fermented into lactate (rather than oxidized through PDH) in GLDC KO cells (Figure 4G). A drop in OGDH activity is evident by feeding cells with [U-13C] glutamine, showing a drop in α-ketoglutarate oxidation and eventually synthesis of M+4 citrate. We also detect an increase in α-ketoglutarate reductive carboxylation and the formation of M+5 citrate (Figure 4H), which is a common phenotype of hypoxic cells or cells with defective mitochondria (Metallo et al., 2012; Mullen et al., 2012). And indeed, the impaired activity of the mitochondrial lipoic acid-dependent complexes in GLDC KO results in a significant 3-fold drop in NADH/NAD+ ratio (Figure 4I; p-value < 0.05) and a significant ~20% decrease in basal and maximal oxygen consumption rates (Figure 4J; p-value < 0.01).

Figure 4. GLDC silencing in HepG2 inhibits lipoic acid-dependent complexes and impairs mitochondrial metabolism.

(A) Mitochondrial oxidation rate in CRISPR-Cas9 GLDC KO HepG2 compared to that in scrambled gRNA (scr) control for a variety of substrates (Biolog Inc. microplates PM-M1; x-axis), and significance two-sided t-test p-value (y-axis) (n = 3).

(B) Schematics of lipoic acid-dependent complexes PDH and OGDH.

(C) and (D) Ratio of substrate to product concentrations for PDH and OGDH (ketoacids to corresponding CoA derivatives) in GLDC KO and SCR HepG2 cells grown in tissue culture (n = 3) (c) and in tumor xenografts (n = 6) (d).

(E) Ratio of substrate to product concentrations for PDH and OGDH (ketoacids to corresponding CoA derivatives) in GLDC KO HepG2 cells fed with 15 μM octanoate for 48 hours (n = 3).

(F) Fractional labeling of citrate in GLDC KO and SCR HepG2 cells fed with [U-13C] glucose.

(G) Fraction of consumed glucose that is fermented into lactate based on media glucose consumption and lactate secretion measurements in GLDC KO and SCR HepG2 cells (n = 3).

(H) Fractional labeling of citrate in GLDC KO and SCR HepG2 cells fed with [U-13C] glutamine (n = 3).

(I) NADH/NAD+ ratio in GLDC KO and SCR HepG2 (n = 3).

(J) Basal and maximal respiration in GLDC KO HepG2 cells compared to SCR. (n = 6).

Data on all panels are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by two-sided Welch’s t-test.

Overall, our work revealed high expression of GCS genes and high glycine cleavage flux in HCC. While previous studies highlighted an important role of glycine uptake for cancer cell proliferation (Jain et al., 2012), usage of glycine-derived 1C units for biosynthesis has not been previously reported in cancer. We developed a systems biology approach for inferring GCS flux, which is excessively over-estimated in previous studies relying solely on measuring 14CO2 when feeding [1-14C] glycine. Utilizing this approach, we found no GCS flux in LN229, which was recently reported to be important in these cells to prevent the production of glycine-derived toxic aldehydes (Kim et al., 2015). Having shown that the silencing of GLDC in HepG2 slows cell proliferation, we found that this is neither due to the accumulation of intracellular glycine; nor because of the shortage of one-carbon units derived from glycine, in agreement with previous reports (Labuschagne et al., 2014). We showed that GLDC KO growth inhibition in HepG2 is due to the inhibition of dihydrolipoyl moiety transfer to PDH that is mediated by GCS H-protein, impairing mitochondrial function.

The newly found importance of GLDC in HCC is in line with previous reports on tissue of origin determining tumor flux rewiring and enzyme dependence (Mayers et al., 2016), considering the physiological role of GCS in liver to maintain glycine homeostasis. Our results suggest GLDC as a novel drug target for HCC, calling for the development of novel chemical inhibitors for GLDC and follow up pre-clinical studies.

Limitations of study

We showed that the lipoic acid-dependent complexes PDH and OGDH are inhibited upon GLDC silencing based on an increase in substrate-product ratio both in cultured cells and in tumor xenografts. We further confirmed a drop in metabolic flux in vitro via 13C glucose and glutamine tracing in GLDC-silenced cells. While technically challenging, performing such isotopic tracing experiments in tumor-bearing mice could further support a repressive mitochondrial metabolic effect of GLDC silencing in vivo. Further work would also be required to support a therapeutic potential of targeting GLDC in HCC; and specifically, whether systemic inhibition of GLDC is sufficiently safe to provide a therapeutic window. A previous report regarding viability of GLDC KO mice (fed with formate to overcome neural tube defects) (Pai et al., 2015) suggests that such a therapeutic window could potentially be achieved. Considering our finding that formate feeding does not rescue growth of GLDC silenced HCC cells, combined treatment with a GLDC inhibitor together with formate as source of 1C units could potentially enable overcoming possible toxic side effects. Further work would be needed to explore whether resistance to drug inhibition of GLDC could emerge, for example via the induction of de novo lipoic acid biosynthesis in cancer cells.

STAR★METHODS

Resource availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Dr. Tomer Shlomi (tomersh@cs.technion.ac.il).

Materials Availability

Plasmids and reagents used to conduct the research detailed in this manuscript are available on request from the Lead Contact, Dr. Tomer Shlomi (tomersh@cs.technion.ac.il).

Data and Code Availability

The original source data underlying all figures are provided as Data S1.

Code used in this study is available on request from the Lead Contact, Dr. Tomer Shlomi (tomersh@cs.technion.ac.il).

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and subject details

Cell Lines

Caco-2 (HTB-37), HEK293T (CRL-3216), Hep3B (HB-8064), HepG2 (HB-8065), HCT-116 (CCL-247), and LN229 (CRL-2611) cell lines were purchased from ATCC. HUH6 cell line is a gift from Professor Uri Nir (Bar-Ilan University). Cell line authentication tests were not conducted in this study. All cell lines were maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium without pyruvate (Biological Industries 01–055-1A, 25 mM glucose) supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (HyClone SH30079.03), 1% penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin B solution (Biological Industries 03–033-1B), and 4 mM glutamine. Cells were maintained in 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. For stable and radioactive isotope tracing, custom formulations of DMEM were used as described in the corresponding sections. Cell lines were regularly checked for Mycoplasma spp. contamination with the EZ-PCR Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Biological Industries 20–700-20).

Mouse Experiments

All mouse experiments were performed under the ethical guidelines of the Technion Administrative Panel of Laboratory Animal Care (animal protocol number: IL_0470317). Mice were housed in a specific-pathogen-free (SPF) facility at 23–25 °C on a 12-h light/dark cycle. HepG2, Hep3B and HUH6 cells were mixed with BD Matrigel™ Matrix Growth Factor Reduced (FAL356231) (1:1 v/v) and injected subcutaneously into the flanks of 7-week female NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid/NCrHsd mice (Envigo). In the experiment with HepG2 GLDC KO, cells were injected subcutaneously (2.5×105 cells per injection) into the right (KO cells) and left flanks (scrambled gRNA cells) of each mouse. HepG2 cells transduced with the lentiviral vector bearing inducible shRNA targeting GLDC were injected similarly with the cell number 106 cells per injection. Doxycycline (5 mg/ml in 0.9% NaCl, 50 μg per gram of body weight) or 0.9% NaCl saline solution were intraperitoneally injected on alternating days, starting two days after grafting. In the experiments with Hep3B and HUH6 GLDC KD, cells were injected subcutaneously (106 cells per injection) into the right (KD cells) and left flanks (SCR cells) of each mouse. Tumor size was measured every 3–4 days with a caliper, and the tumor volume was determined according to the formula: 0.5 × length × width2. Mice were euthanized at the end of the experiment or when the allowable tumor volume was reached. No xenograft tumors exceeded the maximal tumor volume permitted by the Technion Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Xenografts were dissected and weighed.

Method details

Stable isotope tracing and LC-MS metabolomics

Customized DMEM medium formulations were used with the corresponding nutrient substituted to their isotopically labeled counterparts. Medium was supplemented with dFBS and antibiotics as described above. Cells were seeded at least 16 hours prior to the experiment to allow cells to attach and reach the typical division rate. The experiment started with the total replacement of non-labeled medium with the fresh labeled medium. At the end of incubation, cell and medium samples were collected for LC-MS analysis. To extract samples, 5:3 methanol:acetonitrile solution was used for medium samples and 5:3:2 methanol:acetonitrile:water solution – for cell samples (all components of the extraction solutions had LC-MS grade). The extraction solutions were pre-chilled to −20 °C. To collect medium samples, medium aliquots were mixed with the medium extraction solution in the proportion 1:4. Before extracting metabolites from the attached cells, medium was completely aspirated, and cells were washed once with the equal volume of PBS pH 7.4. For 6 cm cell culture dish, 200 μl of the extraction solution was added. Cells were detached from the dish surface by a plastic cell lifter. The content of the dish including cell pellet was transferred to 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes. The tubes were briefly vortexed and then frozen at −80 °C for at least 1 hour. After thawing, tubes were vortexed again. Tubes were centrifuged at 20,800 g for 20 min at 4 °C to remove pellet and stored until the analysis. Before transferring into vials for LC-MS analysis, sample centrifugation was repeated with the same parameters. Metabolites were separated on the SeQuant ZIC-pHILIC column (2.1 × 150 mm, 5 μm beads, Merck KGaA) installed in a UHPLC system Ultimate 3000 Dionex LC system (Thermo). Injection volume was 5 μl for cell extracts and 1 μl for medium extracts. Flow rate was as follows: 0.2 ml·min−1 0–21 min, 0.3 ml·min−1 21–22.1 min, 0.2 ml·min−1 22.1–22.5 min. Solvent A was 20 mM ammonium carbonate with 0.01% (v/v) ammonium hydroxide. Solvent B was 100% acetonitrile. The mobile phase composition (by percentage of the solvent B) was as follows: linear gradient from 80% to 30 % 0–12.5 min, 30% 12.5–15 min, linear gradient from 30% to 80% 15–15.1 min, and maintaining 80% until 22.5 min. Column compartment temperature was maintained at 30 °C, while autosampler tray had 4 °C. Chromatographic eluent was ionized in a HESI-II electrospray ion source and analyzed by a Thermo Q Exactive mass spectrometer. The ion source operated in the polarity-switching mode. Gas parameters: sheath gas 25 AU, auxiliary gas 3 AU, sweep gas was turned off. Spray voltage was switching between −3.3 kV and +4.8 kV, capillary temperature was set at 325 °C, S-lens RF level was 65, auxiliary gas temperature was 200 °C. Metabolites were analyzed in the range 72–1080 m/z. Metabolites were identified by the corresponding chemical standards. Data were reviewed and analyzed in MAVEN (Clasquin et al., 2012). All 13C isotopologue abundances were deisotoped by considering the natural abundance of 13C and the isotope enrichment of the tracers. Absolute metabolite concentrations were quantified by mixing samples with isotopic standards. Metabolite intensities were normalized by total cell volume measured by Beckman-Coulter Z2 Particle Counter.

Measurements of substrate oxidation to CO2

Cells were grown in 12.5 cm2 flasks with 2 ml of medium. Flasks were sealed with gas-tight rubber stoppers. Each flask was equipped with a central well containing 4×4 mm filter paper soaked in 20 μl of concentrated KOH solution at ~60 °C. Medium for tracing experiments was DMEM with low bicarbonate (770 mg/l) and 40 mM HEPES. The final formulation of the medium contained 0.375 μCi/ml of one of the following radioactive tracers: [1-14C] glycine, [2-14C] glycine, or [1,2-14C] serine. The concentration of radioactive tracers was confirmed by measuring scintillation in prepared radioactive media. After 24 h, metabolism was terminated by injecting sulfuric acid to 1 N final concentration through a rubber stopper. Flasks were kept sealed for one hour to collect the residual carbon dioxide in the central wells. Then, the content of central wells was transferred to scintillation vials filled with 10 ml of Perkin-Elmer Ultima Gold® liquid scintillation cocktail, and scintillation was recorded on Perkin-Elmer Tri-Carb 2810 TR scintillation analyzer. Cell volume measurements and stable isotope tracing with [U-13C] serine and [1,2-13C] glycine was performed for cells growing in conditions as described above. Cell volume was measured with Beckman-Coulter Z2 Particle Counter at the beginning and the end of the experiment and the average packed cell volume (PCV) was calculated via approximation of the exponential growth between those timepoints. Carbon dioxide release flux was quantified as previously described (Fan et al., 2014):

where 14CO2 signal represents the measured radioactivity of captured CO2 after 24 hours; SA denotes the specific activity of the 14C tracer (62.43 Ci per mol of 14C); and denote the relative concentration of the non-labeled nutrient and its radioactive isotopomer in the medium. We applied this method to quantify the rate of oxidation of [1-14C] glycine (denoted ), of [2-14C] glycine (denoted ), and of [1,2-14C] serine (denoted ).

Inferring GCS flux via applying a linear operator to substrate oxidation measurements

We utilized the above measurements of substrate oxidation to CO2 to infer three fluxes (Figures S1E-G): (i) The flux through GCS (vGCS(; (ii) glycine-derived 10-formyl-THF oxidation flux via ALDH1L1/2 (vALDH1L(; and (iii) the oxidation flux of serine C1 via phospholipid and sphingosine biosynthesis (or due to isotope exchange with glycolytic intermediates; vSER1).

Feeding [1-14C] glycine, 14CO2 can be released through GCS and through the biosynthesis of serine in which serine C1 is 14C (through SHMT1/2) and subsequent oxidation, and hence:

where denotes the fraction of intracellular glycine having 14C in C1; and denotes the fraction of intracellular serine having 14C in C1, when feeding [1-14C] glycine. We determined and by feeding cells with 13C glycine and using LC-MS to measure the isotopic labeling of intracellular serine and glycine, as LC-MS cannot detect the isotopic labeling of intracellular serine and glycine when feeding with a low non-toxic concentration of the 14C tracers needed.

Feeding [2-14C] glycine, 14CO2 is released solely through the oxidation of 10-formyl-THF and hence:

where denotes the fraction of intracellular glycine having 14C in C2. We inferred , and based on a single isotope tracing experiment, feeding [1,2-13C] glycine (see Inferring the Fractional Labeling of Carbon section of the STAR Methods).

Feeding [1,2-14C] serine, 14CO2 is potentially released through all the above three reactions:

where the fractional labeling coefficients here are determined based on feeding [U-13C] serine (Supplementary Note).

We inferred vGCS, vALDH1L, and vSER1 using the above equations, based on the measured CO2 oxidation rates, serine, and glycine 13C isotopic labeling fractions, considering the experimental measurement noise. Specifically, we repeatedly sampled (10,000 times) values for and from a corresponding normal distribution whose mean and standard deviation are determined by experimental measurements. For each set of samples parameters, we solved the above set of linear equations, deriving a distribution of flux values for vGCS, vALDH1L, and vSER1.

Inferring purine labeling of 10-formyl-THF-derived 1C units

The fractional isotopic labeling of purine carbons derived from the 10-formyl-THF labeling was inferred based on the measured steady state mass isotopic patterns of intracellular glycine and ATP:

where ꕕ represents a convolution of the mass isotopic patterns of glycine and 10-formyl-THF derived 1C units (Fan et al., 2014). In the model, the excess of unlabeled ATP in isotopic steady state was accounted as . We repeatedly sampled (1,000 times) values for the abundances of the isotopic labeling forms of ATP and glycine from a normal distribution whose mean and standard deviation are determined by the measured isotopic labeling patterns done in triplicates. For each set of samples values, we solved 1C labeling based on least square fitting.

Inferring 1C demand flux in HepG2

One-carbon demand in HepG2 was estimated based on following parameters: measured doubling time 35.2±3.5 hours and average cell volume 1600±50 fl; approximate deoxyribonucleotide and ribonucleotide residue molar masses 303.7 and 320.5 g·mol−1, respectively; DNA (10.4 μg/million cells; Kurabo QuickGene DNA) and RNA (28.6 μg/million cells; ABI PRISM™ 6700 Automated Nucleic Acid). Each purine requires two 1C units for biosynthesis, and thymidylate in DNA – one 1C unit. GC content in DNA determines the fraction of dTMP: GC pairs constitute ~41% in human genome (BioNumbers ID 100679). Purine and pyrimidine content in RNA was assumed equal. Flux values were calculated for 100,000 sampled values for the respective normal distributions whose mean and standard deviation are determined experimentally, resulting in 0.61±0.07 and 1.60±0.17 mM·h−1 for DNA and RNA biosynthesis, respectively.

Generation of a stable shRNA knockdown

shRNA sequences were cloned into lentiviral vector pLKO.1 GFP-H2B (GLDC knockdown) and pLKO.1 RFP-H2B (scrambled shRNA control). The shRNA target sequences were as follows:

sh1: 5’- CGTCTGAACTCGCACCTATCA-3’

sh2: 5’-CGAGCCTACTTAAACCAGAAA-3’

shScr: 5’- AACAAGATGAAGAGCACCAA-3’

Cells were transduced with the presence of 10 μg/ml polybrene. Proliferation assays for the cells infected with shRNA targeting GLDC and scrambled shRNA were initiated five days after the removal of viral suspension. For inducible knockdown, shRNA was cloned into Tet-pLKO-puro (purchased from AddGene, 21915).

Generation of GLDC knockout cell lines using CRISPR–Cas9

For HepG2, Hep3B and HUH6 GLDC knockout, cells were transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing hCas9 and two GLDC-targeting gRNA, VectorBuilder cat. no. #6450 and #4921. Control cells were transduced with a vector bearing hCas9 and scrambled gRNA.

gRNA #6450: 5’-TGTGTAGGTCTCAAGCGAGC-3’

gRNA #4921: 5’-TTAATTACTTGGCTCGAGTC-3’

Scrambled gRNA: 5’-GCACTACCAGAGCTAACTCA-3’

Cells were selected with puromycin and used in generating single-cell clones with supplementation of 25 ng/ml recombinant human EGF (Prospec cyt-217-b). After cell population reached ~50,000, EGF supplementation was stopped, and cells grew without stimulation for at least one month with cell confluency maintained above 80%.

Ectopic expression of human GLDC and AMT

LN229 and HepG2 cell lines were prepared for inducible overexpression by transducing with Tet3G lentiviral vector (EF1α promotor, VectorBuilder, VB190308–1157pff). Lentiviral vectors for ectopic expression of full-size unmodified human GLDC (RefSeq NM_000170.2) and AMT (NM_000481.3) under TRE3G doxycycline-inducible promotor were purchased from VectorBuilder (VB181030–1005mhd and VB181029–1224tmq, correspondingly). Transduced cells underwent antibiotic selection, and then used for generating single-cell clones in regular DMEM. In metabolic assays, the ectopic expression was induced by adding 1 μg/ml doxycycline for the duration of the experiment.

Immunoblotting

Cells were washed three times with PBS (pH 7.4). Proteins were extracted with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM NaF) supplemented with 0.5 mM PMSF not earlier than 10 minutes prior to extraction. Cell lysate was collected with a cell scraper, then sonicated (three 15 s bursts interspaced with 10 s idle periods, 2 kJ total energy input, 20 kHz, 20% amplitude) to homogenate and decrease viscosity. Homogenized lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, pellet was discarded. Total protein concentration was measured with Thermo Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (catalog number 23225). For SDS-PAGE sample preparation, lysates were mixed with Laemmli buffer (2% SDS, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 0.002% bromophenol blue, 62.5 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8) and incubated at 95 °C for 10 minutes. Prior to loading, samples were cleared by centrifugation. After SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred on a nitrocellulose membrane with 0.45 μm pores. The membrane was blocked with 5 % skim milk. For 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) treatment, 6 mM final concentration was used. The equivalent volume of RIPA buffer was added to control samples. Samples were incubated for 1 hour at 50 °C and then used in SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as described above.

Cell proliferation assay

Sterile-filtered stock solution of 0.15 mg/ml resazurin in PBS (pH 7.4) is mixed with the fresh DMEM medium in ratio 1:5. For 96-well plates, 100 μl of the mix per well was used. Growth medium is aspirated, and the medium/resazurin mix is added to each well. Cells are returned to an incubator to develop fluorescence for two hours. Fluorescence was detected with 560 nm excitation and 590 nm emission filter set. Background fluorescence was recorded in the wells containing the same volume of DMEM/resazurin mix without live cells.

Octanoate feeding

The initial 15 mM stock of octanoate in 10% (w/v) α-cyclodextrin in water was prepared by stirring the mixture for at least 24 hours at high rotation rate (~800 rpm) followed by sonication. The 15 mM stock of octanoate is a suspension and has a milk appearance. An intermediate stock of 1.5 mM octanoate in 10% α-cyclodextrin was prepared employing another round of sonication. Medium was supplemented with dFBS prior to the octanoate stock addition to prevent octanoate aggregation. Vehicle treatment with the equal volume of 10% α-cyclodextrin solution was applied in all experiments.

Seahorse assay

HepG2 cells were seeded on polylysine-coated 96-well Agilent Seahorse XF Cell Culture Microplate at the density of 12,000 cells per well. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in an incubator with 5% CO2 atmosphere for 12 h. Sensor cartridges were hydrated in Seahorse XF Calibrant at 37 °C in a non-CO2 incubator overnight. Cell medium was replaced by Seahorse DMEM medium (Sigma) supplemented with 2 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM D-glucose, and 2 mM L-glutamine and cells were incubated at 37 °C in a non-CO2 incubator 1 h prior to the measurement. The oxygen consumption rate was measured by Seahorse Bioscience XF96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Agilent Technologies). Cell Mito Stress Test was performed as described by the analyzer manufacturer. Oligomycin at 1 μM final concentration, 2 μM FCCP and 5 μM antimycin and rotenone were added to the medium sequentially. The parameters of cell respiration were calculated according to the Mito Stress Test protocol.

Quantification and statistical analysis

General

Peak intensities were extracted from LC-MS data in MAVEN, as described in the corresponding method above. Statistical analysis was performed in R. Unless noted otherwise, p values were determined using unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t tests. Error bars depict SD (n < 5) or SE (n ≥ 5), as indicated; p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Inferring the fractional labeling of carbon at specific positions in glycine and serine

Parameter

We estimated the fraction of the [1 0] isotopomer of intracellular glycine in cells fed with [1-14C] glycine (denoted by ) based on LC-MS measurements in cells fed with [1,2-13C] glycine. First, we consider a balance equation for the isotopomer distribution of intracellular glycine in case of [1-14C] glycine feeding:

| (1) |

where represents the dilution of intracellular serine by de novo biosynthesis and serine uptake from the medium. We denote by the isotopic labeling pattern of glycine produced by reverse GLDC flux, which is fully unlabeled as cells are exposed to 12CO2 originating from the unlabeled bicarbonate, and methylene-THF cannot get labeled from the fed tracer having the 1st carbon of glycine labeled, according to the following reaction scheme:

Hence:

| (2) |

In case of [1,2-13C] glycine feeding, the balance equation has the following form:

| (3) |

Hence:

| (4) |

| (5) |

Hence, can be estimated based on the measured M+2 of intracellular glycine in case of [1,2-13C] glycine feeding.

Parameter

The labeling of the first carbon of intracellular serine in case of [1-14C] glycine feeding, according to (1), is:

| (6) |

while in case of [1,2-13C] glycine feeding (3):

| (7) |

Considering (5), we find that

| (8) |

Therefore, can be determined as the sum of M+2 and M+3 serine in cells fed with [1,2-13C] glycine.

Parameter

To find (the fraction of glycine with the second carbon labeled in cells fed with [2-14C] glycine), we consider the following balance equation describing feeding with [2-14C] glycine:

| (9) |

| (10) |

In case of [1,2-13C] glycine feeding (3):

| (11) |

Considering that it is the 2nd carbon of glycine which is transferred to methylene-THF, and are equal, and hence

and so is equal to the sum of M+1 and M+2 glycine isotopologues in cells fed with [1,2-13C] glycine.

Parameter

We can write the following balance equation for glycine in cells fed with [1,2-14C] serine:

| (12) |

where denotes the dilution of serine that is produced internally by serine de novo biosynthesis and denotes the dilution of intracellular serine by serine uptake from the medium. From (12) we define:

| (13) |

A balance equation for the case of [U-13C] serine feeding is following:

| (14) |

From (14) we have:

| (15) |

| (16) |

Hence, the labeling of the first carbon in glycine ( in cells fed with [1,2-14C] serine can be estimated based on M+2 glycine in cells fed with [U-13C] serine.

Parameter

The labeling of the second carbon of glycine in cells fed with [1,2-14C] serine (12):

| (17) |

Based on (12), we can write for

| (18) |

Based on (14):

| (19) |

Considering that , we get that:

| (20) |

Given that M+1 glycine M+2 glycine when feeding [U-13C] serine (Supplementary Table S1), and Equations (16–17):

| (21) |

Thus, we can estimate based on M+2 glycine in cells fed with [U-13C] serine.

Parameter

The labeling of the first carbon of intracellular serine in cells fed with [1,2-14C] serine (12):

| (22) |

Based on (14), the labeling of the first carbon of serine in cells fed with [U-13C] serine:

| (23) |

Considering (16):

| (24) |

Considering that (based on M+1 glycine M+2 glycine when feeding [U-13C] serine), Equation (14) entails that . Hence, can be estimated based on M+2 serine, and equals to the sum of M+2 and M+3 serine.

Supplementary Material

Data S2. Data underlying the display items in the manuscript, related to Figures 1–4 and S1-4.

Data S1. The images of representative western blots, related to Figures 2, 3, S1, S3, and S4.

Table S2. Decomposed flux, related to Figure 1.

Table S1. 14CO2 measurements, related to Figure 1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yaron Fuchs, Dr. Eyal Gottlieb, and Dr. Joshua Rabinowitz for scientific discussions. The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council/ERC Grant Agreement No. 714738 and was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science & Technology of the State of Israel & German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ). Additionally, this work was supported by grants NIH NCI DP2 CA249950-01 and NIH P30 CA010815 (Wistar Institute).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

T.S. is a co-founder and consultant in MetaboMed Ltd.

Data availability

Source data used to generate all figures in the article are provided as Supplementary Data. Other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, Wilson CJ, Lehár J, Kryukov GV, Sonkin D, et al. (2012). The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature 483, 603–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bartolomeo F, Wagner A, and Daum G. (2017). Cell biology, physiology and enzymology of phosphatidylserine decarboxylase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1862, 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Zhu L, Song X, Hu Z, and Cronan JE (2018). Protein moonlighting elucidates the essential human pathway catalyzing lipoic acid assembly on its cognate enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115, E7063–E7072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasquin MF, Melamud E, and Rabinowitz JD (2012). LC-MS data processing with MAVEN: a metabolomic analysis and visualization engine. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics Chapter 14, Unit14.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducker GSS, Chen L, Morscher RJJ, Ghergurovich JMM, Esposito M, Teng X, Kang Y, Rabinowitz JDD, Ducker GSS, Chen L, et al. (2016). Reversal of Cytosolic One-Carbon Flux Compensates for Loss of the Mitochondrial Folate Pathway. Cell Metab. 23, 1140–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Ye J, Kamphorst JJ, Shlomi T, Thompson CB, and Rabinowitz JD (2014). Quantitative flux analysis reveals folate-dependent NADPH production. Nature 510, 298–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GTEx Consortium (2020). The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 369, 1318–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada K. (2003). Serine palmitoyltransferase, a key enzyme of sphingolipid metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1632, 16–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter C, and Zenklusen JC (2018). The Cancer Genome Atlas: Creating Lasting Value beyond Its Data. Cell 173, 283–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M, Nilsson R, Sharma S, Madhusudhan N, Kitami T, Souza AL, Kafri R, Kirschner MW, Clish CB, and Mootha VK (2012). Metabolite Profiling Identifies a Key Role for Glycine in Rapid Cancer Cell Proliferation. Science (80-. ). 336, 1040–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi G, Motokawa Y, Yoshida T, and Hiraga K. (2008). Glycine cleavage system: reaction mechanism, physiological significance, and hyperglycinemia. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B. Phys. Biol. Sci 84, 246–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Fiske BP, Birsoy K, Freinkman E, Kami K, Possemato RL, Chudnovsky Y, Pacold ME, Chen WW, Cantor JR, et al. (2015). SHMT2 drives glioma cell survival in ischaemia but imposes a dependence on glycine clearance. Nature 520, 363–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labuschagne CF, van den Broek NJF, Mackay GM, Vousden KH, and Maddocks ODK (2014). Serine, but not glycine, supports one-carbon metabolism and proliferation of cancer cells. Cell Rep. 7, 1248–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WD, Pirona AC, Sarvin B, Stern A, Nevo-Dinur K, Besser E, Sarvin N, Lagziel S, Mukha D, Raz S, et al. (2021). Tumor Reliance on Cytosolic versus Mitochondrial One-Carbon Flux Depends on Folate Availability. Cell Metab. 33, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locasale JW, Grassian AR, Melman T, Lyssiotis CA, Mattaini KR, Bass AJ, Heffron G, Metallo CM, Muranen T, Sharfi H, et al. (2011). Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase diverts glycolytic flux and contributes to oncogenesis. Nat. Genet 43, 869–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayers JR, Torrence ME, Danai LV, Papagiannakopoulos T, Davidson SM, Bauer MR, Lau AN, Ji BW, Dixit PD, Hosios AM, et al. (2016). Tissue of origin dictates branched-chain amino acid metabolism in mutant Kras-driven cancers. Science (80-. ). 353, 1161–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metallo CM, Gameiro PA, Bell EL, Mattaini KR, Yang J, Hiller K, Jewell CM, Johnson ZR, Irvine DJ, Guarente L, et al. (2012). Reductive glutamine metabolism by IDH1 mediates lipogenesis under hypoxia. Nature 481, 380–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minton DR, Nam M, McLaughlin DJ, Shin J, Bayraktar EC, Alvarez SW, Sviderskiy VO, Papagiannakopoulos T, Sabatini DM, Birsoy K, et al. (2018). Serine Catabolism by SHMT2 Is Required for Proper Mitochondrial Translation Initiation and Maintenance of Formylmethionyl-tRNAs. Mol. Cell 69, 610–621.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morscher RJ, Ducker GS, Li SH-J, Mayer JA, Gitai Z, Sperl W, and Rabinowitz JD (2018). Mitochondrial translation requires folate-dependent tRNA methylation. Nature 554, 128–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullarky E, Mattaini KR, Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, and Locasale JW (2011). PHGDH amplification and altered glucose metabolism in human melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 24, 1112–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen AR, Wheaton WW, Jin ES, Chen PH, Sullivan LB, Cheng T, Yang Y, Linehan WM, Chandel NS, and Deberardinis RJ (2012). Reductive carboxylation supports growth in tumour cells with defective mitochondria. Nature 481, 385–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai YJ, Leung KY, Savery D, Hutchin T, Prunty H, Heales S, Brosnan ME, Brosnan JT, Copp AJ, and Greene ND (2015). Glycine decarboxylase deficiency causes neural tube defects and features of non-ketotic hyperglycinemia in mice. Nat Commun 6, 6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollari S, Käkönen SM, Edgren H, Wolf M, Kohonen P, Sara H, Guise T, Nees M, and Kallioniemi O. (2011). Enhanced serine production by bone metastatic breast cancer cells stimulates osteoclastogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat 125, 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possemato R, Marks KM, Shaul YD, Pacold ME, Kim D, Birsoy KK, Sethumadhavan S, Woo H-KK, Jang HG, Jha AK, et al. (2011). Functional genomics reveal that the serine synthesis pathway is essential in breast cancer. Nature 476, 346–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solmonson A, and DeBerardinis RJ (2018). Lipoic acid metabolism and mitochondrial redox regulation. J. Biol. Chem 293, 7522–7530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent DF, Maddocks ODK, Vousden KH, Athineos D, Cheung EC, Ceteci F, Kruiswijk F, Labuschagne CF, Blagih J, Zhang T, et al. (2017). Modulating the therapeutic response of tumours to dietary serine and glycine starvation. Nature 544, 372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WC, Ng SC, Yang H, Rai A, Umashankar S, Ma S, Soh BS, Sun LL, Tai BC, Nga ME, et al. (2012). Glycine decarboxylase activity drives non-small cell lung cancer tumor-initiating cells and tumorigenesis. Cell 148, 259–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S2. Data underlying the display items in the manuscript, related to Figures 1–4 and S1-4.

Data S1. The images of representative western blots, related to Figures 2, 3, S1, S3, and S4.

Table S2. Decomposed flux, related to Figure 1.

Table S1. 14CO2 measurements, related to Figure 1.

Data Availability Statement

The original source data underlying all figures are provided as Data S1.

Code used in this study is available on request from the Lead Contact, Dr. Tomer Shlomi (tomersh@cs.technion.ac.il).

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Source data used to generate all figures in the article are provided as Supplementary Data. Other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.