Abstract

This study examined the factor structure of executive control throughout elementary school, as well as associations between executive control abilities in preschool and elementary school. Data were drawn from a longitudinal study of executive control development in a community sample of children (N = 294; 53% female, 47% male) oversampled for low family income (25.4% below poverty line; Mincome = $46,638; SD = $33,256). The sample was representative of the Midwestern city in which the study was conducted in terms of race (71.4% White, 24.5% multiracial, 3.7% Black, and .3% Asian American) and ethnicity (14% Hispanic). Children completed a battery of ten performance-based tasks assessing executive control abilities in grades 1 (Mage = 7.08 years), 2 (Mage = 8.04 years), 3 (Mage = 9.02 years), and 4 (Mage = 9.98 years). Confirmatory factor analysis supported a two-factor structure at each grade with factors representing working memory and inhibitory control/flexible shifting. Measurement invariance testing revealed partial scalar (indicator intercepts) invariance for working memory and partial metric (indicator loadings) and partial scalar invariance for inhibitory control/flexible shifting. Preschool executive control (age 4.5 years), represented by a unitary latent factor, significantly predicted working memory (βs = .79, .72, .81, .66) and inhibitory control/flexible shifting (βs = .69, .64, .63, .62) factors in grades 1 through 4. Follow-up analyses indicated that the findings were not due to general cognitive ability. Findings support greater separability of executive control components in elementary school versus preschool, and considerable continuity of executive control from preschool through elementary school.

Keywords: executive control, factor structure, elementary school, preschool, inhibitory control, working memory

Executive control (also known as “executive functioning” or “EF”),1 a set of related abilities critical to directing attention and behavior (Diamond, 2013; Espy, 2016; Garon et al., 2008), begins to develop early in life and impacts educational, mental health and physical health outcomes (Blair & Razza, 2007; Hughes & Ensor, 2011; Nelson et al., 2017; Nelson et al., 2018a). Given increasing recognition of executive control’s role across various areas of functioning, considerable research has focused on describing the development and structure of executive control abilities in childhood and adolescence. Much of this literature has focused on executive control during the critical periods of preschool (e.g., Espy, 2016; Willoughby et al., 2012) and adolescence (e.g., Li et al., 2015), with relatively fewer studies examining executive control during the elementary school period. Within the elementary school executive control literature, most studies include a single measurement point, and there are fewer longitudinal studies with multiple measures of executive control across elementary school. Further, studies exploring executive control across the preschool and elementary school periods are rare, particularly in the context of examinations that carefully consider factor structure at different points in development. This gap leaves important questions regarding the nature of continuity and change in the executive control construct from early childhood to late childhood. Leveraging data from a unique longitudinal study of executive control development in a community sample, the present study seeks to replicate and extend prior research by both rigorously examining the factor structure of executive control throughout elementary school, and investigating longitudinal associations between executive control abilities in preschool and elementary school.

The Structure of Executive Control: “Unity and Diversity”

Executive control is typically conceptualized as comprised of multiple related cognitive abilities. While models vary in terms of the number of abilities represented, as well as the exact labels used to describe those abilities, the most common conceptualization of executive control includes three main components: working memory (holding information in mind and manipulating it); inhibitory control (stopping prepotent responses); and flexible shifting (switching between changing task demands) (Best & Miller, 2010; Espy, 2016). The overlap and distinctiveness of these core executive control abilities has received substantial theoretical and empirical attention in the literature. In terms of theory, the “unity and diversity” framework (Friedman & Miyake, 2017; Miyake et al., 2000) suggests that executive control abilities are significantly correlated with each other reflecting something in common (“unity”), but also separable into distinct constructs or factors (“diversity”). The unity and diversity model has spurred numerous investigations into the factor structure of executive control at different developmental stages, with an emphasis on determining the degree of separability among executive control abilities at different ages. As described in the literature review below, the vast majority of studies on executive control factor structure have focused on describing executive control at a particular age or developmental period; however, studies exploring changes in factor structure across different ages and developmental periods using longitudinal methods are more limited. Further, a smaller literature has addressed the issue of differentiation (i.e., the separation of executive control abilities over time), leaving a notable gap in our knowledge of the developmental trajectory of executive control factor structure.

Executive Control in Preschool and Adolescence

Preschool has long been recognized as a critical period for the development of executive control, characterized by substantial gains in abilities reflecting rapid brain development (Clark et al., 2016; Moriguchi & Hiraki, 2013; Espy, 2016). A large and rigorous body of literature has explored the factor structure of executive control during preschool, with findings generally pointing to a unitary construct as the preferred representation (Fuhs & Day, 2011; Hughes et al., 2010; Wiebe et al., 2011; Willoughby et al., 2012; see Miller et al., 2012, for different findings). Further, although executive control abilities appear to be largely indistinguishable from more foundational cognitive abilities (FCA) early in preschool, executive control begins to differentiate from FCA later in preschool, with some literature suggesting executive control emerges as a distinct construct by age 4.5 years (Espy, 2016). In addition to research documenting the development and structure of early executive control, numerous studies have found individual differences in executive control during preschool to predict a wide range of educational (Blair & Razza, 2007), behavioral and emotional (Espy et al., 2011; Hughes & Ensor 2011; Nelson et al., 2018a), and health outcomes (Nelson et al., 2017; Nelson et al., 2018b). Such work highlights the importance of early executive control in shaping healthy development.

Executive control is notable for its protracted developmental course from early in life through early adulthood, paralleling development of the prefrontal cortex and connections to other brain regions (Espy, 2016; Luna et al., 2010; Luna et al., 2015). Therefore, while the study of executive control in preschool has garnered much attention, so too has executive control later in its developmental progression. In particular, adolescence is often conceptualized as another critical period in executive control development, with growing and changing abilities influenced by substantial reorganization in the brain during this period (Fuhrmann et al., 2015). Although specific findings vary by study based on differences in measurement and conceptual approach, research on adolescent executive control consistently finds a more differentiated structure than the unitary factor reported in preschool. For example, one study found a three-factor structure of executive control using the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) in a cross-sectional examination of 142 adolescents ages 12 to 15 (Li et al., 2015). Similarly, a large study in Singapore reported a three-factor executive control structure at age 15, including distinct but related factors of updating (working memory), inhibition, and shifting (Lee et al., 2013). Other cross-sectional studies have reported distinct working memory and inhibition factors (McAuley & White, 2011; Shing et al., 2010) in adolescent samples (although these studies did not include shifting tasks, thus precluding an examination of the separability of a shifting construct). Taken together, the literature on adolescent executive control suggests significant separability between executive control abilities such as working memory, inhibitory control, and flexible shifting, roughly paralleling the differentiated structure of mature executive control into young adulthood (Miyake et al., 2000).

What Happens in Between: Executive Control in Elementary School

Although much is known about the structure of executive control in preschool and in adolescence, less literature describes the structure of executive control in between these periods. However, recently, researchers have increasingly recognized the gap in knowledge about executive control in elementary school, and studies have begun to examine executive control structure during this understudied period. Consistent with the concept of unity and diversity (Miyake et al. 2000), the vast majority of studies suggest some degree of separability of executive control components is observable in elementary school. Among cross-sectional investigations of factor structure in elementary school, numerous studies spanning different cultures have found three-factor solutions, generally corresponding to working memory, inhibitory control, and flexible shifting (e.g., Arán-Filippetti et al., 2013; Lehto et al., 2003; Rose et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2011). These studies provide valuable “snapshots” of executive control structure at specific points in elementary school but are limited by cross-sectional designs and the inability to explore how factor structure may change over time. In contrast, studies with longitudinal designs have tended to report two-factor structures emerge at some point in elementary school (e.g., Brydges et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2013; van der Ven et al., 2013; Usai et al., 2014) and that the three-factor structure does not emerge until adolescence (Lee et al., 2013).

Despite the apparent conflict between findings from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, it is notable that some of the strongest investigations of elementary school executive control factor structure – often characterized by large samples, robust task batteries, and repeated measures at different time points in elementary school – have converged on similar two-factor structures. For example, longitudinal studies in Singapore (Lee et al., 2013) and the Netherlands (van der Ven et al., 2013) found two-factor structures with separate working memory and inhibitory control/flexible shifting factors across multiple time points in elementary school. Another study with an Australian sample (Brydges et al., 2014) reported a unitary factor at age 8.25 years but a two-factor structure – also working memory and inhibitory control/flexible shifting – at age 10.25 years. Taken together, these longitudinal studies, across diverse cultural contexts, place the most compelling current evidence in support of a partially-differentiated, two-factor structure of executive control in elementary school, although important questions remain.

The extant literature on executive control factor structure in elementary school provides important building blocks for replication and extension in the current study. Although some of the stronger longitudinal designs point to a two-factor (working memory and inhibitory control/flexible shifting) structure emerging in elementary school, even the most rigorous previous studies have important limitations that merit replication and extension. First, some previous studies (e.g., Lee et al., 2013) used different conditions of the same tasks to measure inhibitory control and flexible shifting abilities, potentially inflating the overlap between these abilities and limiting the ability to detect separability. Second, the longitudinal study with the largest sample and the most measurement points (Lee et al., 2013) was limited in its ability to explore longitudinal associations between executive control factors at different ages because the study design and attrition resulted in overlapping but substantially different samples of children at different ages. Third, and addressing a more exploratory question, the potential separability of two types of inhibitory control – response inhibition and interference suppression (discussed below) – has not been examined in studies of executive control factor structure in elementary school. Addressing these methodological and substantive issues, as well as replicating previous findings in a longitudinal sample in the United States, is an important focus of the current study.

Differentiation Within Inhibitory Control

In addition to differentiation over time between the three most commonly identified components of executive control (i.e., working memory, inhibitory control, flexible shifting), it is possible that differentiation may occur within some of these components. In particular, some researchers have proposed that inhibitory control can be conceptualized as two related but distinct abilities: response inhibition (the ability to refrain from a specific prepotent behavioral response) and interference suppression inhibition (the ability to inhibit attention to distracting stimuli). One study found that these forms of inhibitory control were related but distinct abilities in testing with adults (Friedman & Miyake, 2004), and multiple event-related potential (ERP) studies have found evidence for differences in neural activation during response inhibition and interference suppression in adults but not children (Brydges et al., 2013; Vuillier et al., 2016). However, previous studies examining the factor structure of executive control in childhood have not explored whether response inhibition and interference suppression inhibition are separable within this developmental period. Further, although previous studies have found evidence of separability with inhibitory control in adults but not children as young as 8 years old (e.g., Vuillier et al., 2016), studies exploring separability within inhibitory control using repeated assessment of children are lacking. This gap leaves an important developmental question as to when in development this differentiation may occur. The current study is the first to our knowledge to directly examine the question of differentiation within inhibitory control in the context of a broader examination of executive control factor structure in childhood.

Developmental Processes Underlying Differentiation of Executive Control

Theoretical and empirical work points to developmental processes that may underlie increasing executive control differentiation with age. Leading theories suggest that early in development, broad brain regions and networks are recruited in response to a wide range of executive control tasks, resulting in highly correlated and inseparable performance on different types of executive control tasks. However, as children move through elementary school, networks become more specialized and task-specific, potentially leading to decreasing correlations in performance across diverse tasks (Bardikoff & Sabbagh, 2017; Johnson, 2011; Moriguchi et al., 2017). Providing further support for this idea, a recent study found that compared to 5-6 year olds, 8-9 year old children showed more differentiated recruitment within the prefrontal cortex while completing a cognitive task requiring inhibition and set-shifting, suggesting increasingly efficient control as children mature in elementary school (Chevalier et al., 2019). Mechanisms underlying this increasing efficiency could include cortex pruning and prefrontal pruning processes that begin in elementary school and continue through adolescence (Kolb et al., 2012). These developmental changes in specialization and efficiency could explain a general progression from an early unitary executive control factor structure to increasingly differentiated structures later in childhood and beyond; however, the timing and degree of this differentiation at points along that progression remains largely unknown. Carefully documenting progressions in executive control factor structure is critical for understanding typical developmental patterns of differentiation during the long, and largely understudied period of elementary school, and for filling in gaps in our knowledge of executive control development between preschool and adolescence.

Continuity and Change in Executive Control Structure from Preschool to Elementary School

In addition to replication and extension of earlier work investigating executive control factor structure during elementary school, the current study also addresses an important developmental question regarding the continuity of executive control abilities from preschool through elementary school. Preschool is widely regarded as a critical period in the development of executive control abilities (Espy, 2016), but very few studies have explored the continuity of abilities from this critical period into later developmental periods. Other studies have documented longitudinal associations between specific aspects of executive control (e.g., working memory) at different points in development (e.g., Ahmed et al., 2019), but these studies did not have a sufficient number of tasks to represent the changing structure of executive control across development, leaving associations between early unitary executive control and later, potentially more differentiated, executive control factors unexplored. In fact, we are not aware of any studies that have examined associations between executive control in preschool and executive control throughout elementary school in a longitudinal study with comprehensive executive control measurement and attention to relevant factor structures in both periods. Such a study could make a critical contribution in delineating how early executive control relates to specific components of executive control as they differentiate later in childhood, thus describing aspects of both continuity and change as executive control develops.

The Present Study

The present study seeks to replicate and extend findings from previous studies of executive control factor structure in elementary school, leveraging data from a longitudinal study of typical executive control development spanning preschool through elementary school. First, the current study builds on prior research by using a robust battery of tasks to assess child executive control abilities (including separate tasks for working memory, inhibitory control, and flexible shifting), following a sample of children originally recruited in preschool and repeatedly assessed annually in grades 1 through 4, and examining competing factor structures to determine the best representation of executive control at each elementary school grade. We examine multiple conceptually relevant factor structures representing different degrees and configurations of separability between executive control components, as well as a more exploratory examination of possible separability within inhibitory control (see Figure 1). Capitalizing on the repeated assessment of substantially the same sample across elementary school, we also explore the stability of executive control factor structure across elementary school by testing for longitudinal measurement invariance. Second, and extending beyond the focus of previous research, the current study examines longitudinal associations between the established unitary EC executive control construct in preschool and specific separate components (if applicable) in elementary school. To determine the extent to which continuity in executive control is independent of continuity in general cognitive ability, we also conduct follow-up analyses that examine these longitudinal associations while controlling for general cognitive ability. This novel analysis of longitudinal associations between executive control during distinct developmental periods, with potentially different factors structures, will inform our understanding of the continuity of executive control abilities across a period of protracted structural change.

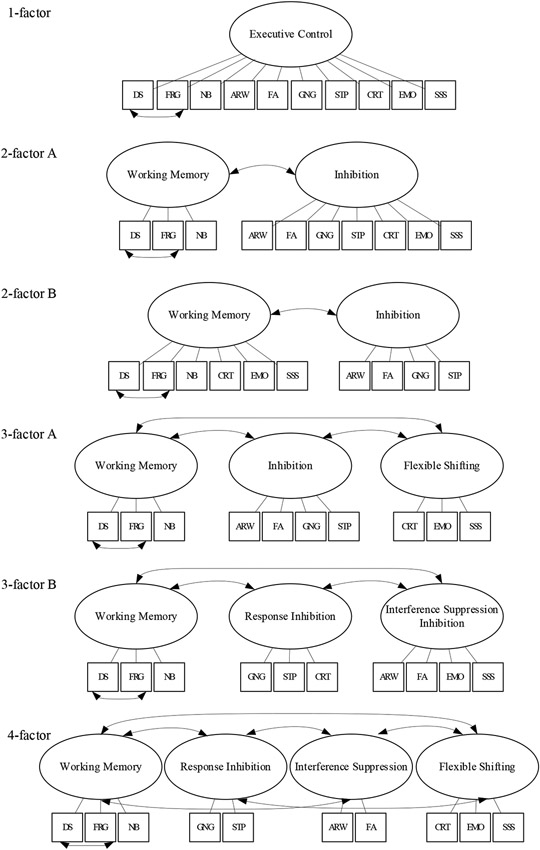

Figure 1. Theoretical Models of Executive Control Structure in Elementary School.

Note. Each sub-figure represents a theoretical measurement model of executive control in elementary school; these models were evaluated in grades 1 through 4 (see Table 3 for model comparisons at each grade). DS = Digit Span. FRG = Jumping Frog. NB = Nebraska Barnyard. GNG = Go/No-Go. STP = Stop Signal. FA = Funny Animals. ARW = Arrows. CRT = Creatures. EMO = Emotion Stroop. SSS = Shape School - Switching.

Based on developmental perspectives on prefrontal cortex specialization during elementary school (e.g., Moriguchi et al., 2017; Chevalier et al., 2019), we hypothesize that a factor structure somewhere between the unitary factor structure of preschool and the three-factor structure of adolescence and young adulthood will provide the best representation of executive control in elementary school. More specifically, and consistent with findings from previous longitudinal studies of executive control factor structure in elementary school (e.g., Lee et al., 2013; Brydges et al., 2014; van der Ven et al., 2013), we expect a two-factor structure with separate factors for working memory and inhibitory control/flexible shifting. With regard to the exploratory analysis of separability within inhibitory control, there is insufficient literature in this area to reliably inform specific hypotheses regarding whether these different types of inhibition will be separable in elementary school. We also hypothesize significant longitudinal associations between executive control in preschool (represented by a unitary latent construct) and executive control in elementary school (represented by a more differentiated set of factors, if applicable), reflecting substantial continuity in executive control abilities even as the factor structure of executive control changes.

Method

Participants

The participants were 294 children (53% female) from a longitudinal study on executive control development in preschool and elementary school. Participating families were recruited from the community in a small Midwestern city when the target child was in preschool. Because the study focused on capturing typical executive control development, children with a diagnosed developmental, behavioral, or language disorder at the time of study enrollment in preschool were excluded. Children whose parents reported they were diagnosed with speech or language disorders subsequent to enrollment during the preschool phase (but not in the elementary school elementary school phase) were also excluded. Those diagnosed with a behavioral or emotional disorder after initial recruitment were not excluded. The racial and ethnic composition of the sample was representative of the city and region from which it was recruited (US Census, 2019; Lincoln Public Schools, 2021), however, it was not representative of the broader United States population. Specifically, the ethnic composition of the sample was 86% non-Hispanic and 14% Hispanic; the racial composition of the sample was 71.4% White, 24.5% multiracial, 3.7% Black, and .3% Asian American. The study oversampled for children from families with low income, with 25.4% of families reporting income below the poverty line at the time of enrollment. The mean family income for the sample was $46,638 (SD = $33,256), and 57% received public medical assistance at the time of enrollment based on parent report. Mean child age at each assessment point was 4.46 years (SD = 0.04 years; range = 4.42 – 4.50 years) at the preschool timepoint, 7.08 years (SD = 0.34 years, range = 6.33 – 8.00 years) at grade 1, 8.04 years (SD = 0.35 years, range = 7.25 – 8.92 years) at grade 2, 9.02 years (SD = 0.38 years, range = 8.25 – 10.00 years) at grade 3, and 9.98 years (SD = 0.35 years, range = 9.25 – 10.83 years) at grade 4.

Procedures

To assess executive control abilities in elementary school, the participants completed a battery of 10 individually-administered and developmentally-appropriate executive control tasks each spring in grades 1 (n = 218), 2 (n = 260), 3 (n = 271), and 4 (n = 252). (Note: Sample sizes are somewhat smaller in grade 1 and grade 4 due to the timing of funding and the lagged cohort sequential design of the longitudinal study. A subset of the sample was already past grade 1 at the start of the elementary school assessment phase. At the other end, a subset of the sample was not able to complete the grade 4 assessment because funding ended before these children reached fourth grade.) The total number of children who were assessed at least once during grades 1-4 was 294, which is considered the total sample size of the current study. The majority of these children (n = 209; 71%) also participated in an earlier laboratory-based testing session at age 4.5 years. Given the lagged cohort sequential design of the larger longitudinal study, 83 children enrolled in the original study at 5.25 years or 6 years old; therefore, they do not have executive control assessment data at age 4.5 years, but they did participate in the executive control assessments throughout elementary school. Two other children were enrolled in the preschool phase but missed the age 4.5 years assessment, and then participated in elementary school. Testing at the age 4.5 years preschool time point included a battery of 9 individually-administered and developmentally-appropriate tasks designed to measure the main components of executive control. Parents or legal guardians provided informed consent in elementary and preschool, and children provided assent in late elementary. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln under protocol #2015-11-113EP, “Executive function development in preschool children.”

Measures

Elementary School Executive Control.

Executive control abilities in grades 1-4 were assessed using a battery of 10 neuropsychological tasks that paralleled the preschool executive control battery with strategic extensions, substitutions, and scoring changes to ensure the tasks were developmentally appropriate and produced sufficient variability. The tasks spanned the three main components of executive control: working memory, inhibitory control, and flexible shifting.

For working memory, three tasks were administered: Digit Span, Jumping Frog, and Nebraska Barnyard.

Digit Span is a verbal working memory task taken from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fourth Edition (WISC-IV; Wechsler, 2003). The child listens as the examiner verbally presents a sequence of single digit numbers before children then verbally repeat back the same numbers. There are two parts to the task – a forward condition and a backward condition – and sequence length progressively increases until the child meets discontinuation criteria. The maximum span length is nine digits in the forward condition and eight digits in the backward condition. Raw correct trial sum on the backward condition was used in the current study because it represents performance on a more difficult task involving manipulation of remembered information. Higher scores indicate better performance.

Jumping Frog is a computerized visual-spatial span task adapted from the Corsi Blocks (Milner, 2011) in which the child watches an animated frog hop between nine lily pads on a screen, before then using a touch screen to touch the respective lily pads in the same order as the frog. Similar to Digit Span, the task includes two parts – the forward condition, which involves touching the lily pads in the same order at the frog, and backward condition, which involves touching the pad in the reverse order. Sequence length increases progressively until the child meets the discontinuation criteria, with a maximum of eight block of forward trials (with sequences of two to nine lily pads) and up to seven blocks of backward trials (with sequences of two to eight lily pads). Correct trial total for the backward condition was used as the dependent variable in the current study because it represents performance on a more challenging task demanding manipulation of the sequence that is held in working memory. Higher scores indicate better performance.

Nebraska Barnyard is a computerized task adapted from the Noisy Book task (Hughes et al., 1998), assessing working memory using verbal and visual-spatial information. The child must remember a sequence of animal names that they then transform into a color sequence before pressing the corresponding colored buttons in the correct order on a touch screen. In the initial training phase, the child is introduced to a set of nine colored pictures of barnyard animals arranged in a 3x3 grid of colored boxes on the screen. As the child presses the animal boxes, a corresponding animal sound is produced. Thereafter, the animal pictures are removed. The child completes a set of nine trials during which the examiner names each animal individually, and the child is asked to press the box corresponding to that animal. Trials with sequences of animals are administered, beginning with sequences of two animals and increasing progressively until the child meets discontinue criteria, with a maximum span length of nine animals. Correct trial total was used as the dependent variable, with higher scores indicating better performance. Correct trials with a sequence length of one were given a value of .33; all other correct trials were given a value of 1 to give more weight to trials involving sequences with multiple animals to recall. Higher scores indicate better performance.

For inhibitory control, a total of four tasks were administered. Two of these tasks, (Go/No-Go and Stop Signal) assess response inhibition, and two tasks (Funny Animals and Arrows) assess interference suppression inhibition.

Go/No-Go (adapted from Simpson & Riggs, 2006) is a computerized task in which the child is presented with pictures of colored fish and asked to “catch” these fish by responding on a button box. On less frequent “no-go” trials (25% of trials), a stimulus image of a shark appears, and children are instructed to “let it go” by withholding the button press response, hence requiring response inhibition. Feedback is provided in the form of a fishing net, which breaks when children make an error of commission by pressing the button in response to the shark stimulus. The dependent variable is d-prime, which is a sensitivity measure capturing a standardized difference between the child’s hit rate and false alarm rate. Higher scores indicate better performance.

Stop Signal is a computerized task adapted from a task used by Blaskey and colleagues (2008) in which the child must discriminate between animated fish swimming either to the left or the right on the screen by pressing the corresponding left or right button on a button box as quickly as possible. On 25% of the trials, the child is presented with an auditory and visual “stop” signal (in the form of a boat picture and accompanying sound), which signifies that they must inhibit their button press response. The program is calibrated to track the child’s performance and adjust the length of time between the stop signal and the stimulus, making it easier or more difficult to inhibit based on previous performance. Percent correct on the stop trials was used in the analyses, with higher scores indicating better performance.

Funny Animals is a Stroop-like task adapted from a task used by Wright and colleagues (Wright et al., 2003) in which the child is presented animated animals whose heads and bodies often mismatch. The child is asked to name the relatively less salient bodies while resisting the interference created by more salient head information. Forty percent of the trials are incongruent (different head and body), 40% are congruent (same head and body), and 20% are irrelevant (head is a square with facial features, not an animal head). The child is asked to verbally name each animal as quickly as possible. The dependent variable is a bin score derived from the rank-order binning procedure proposed by Hughes et al. (2014). This score has the advantage of combining accuracy and response time to create a single comprehensive score reflecting performance on the task. The bin score variable is calculated in five steps. The first step is to calculate the mean response time for correct congruent trials per individual at each time point. In step 2, the mean response time from step 1 is subtracted from the response time of each correct incongruent trial within the individual. In step 3, the correct incongruent trials are then ranked from lowest to highest adjusted response time from step 2 across all individuals. Once ranked, these trials are given a score from 1 to 10 based on their ranking, with a score of 1 given to the lowest ten percent of trials, a score of 2 given to the next lowest ten percent of trials, and so on up to a score of 10 given to the highest ten percent of trials. Step 4 is to assign all incorrect incongruent trials a score of 20. The final step sums the ranking scores assigned in steps 3 and 4 for all incongruent trials within an individual, creating one bin sum score per individual at each time point. Lower scores represent better performance.

Arrows is a task adapted from a task used by Davidson and colleagues (2006) in which the child views a series of arrows on a screen. Each arrow points either left or right and appears on either the left or right side of the screen. Congruent trials occur when the direction of the arrow and the side of the screen are consistent; incongruent trials occur when the direction of the arrow conflicts with the side of the screen. The child is asked to press a button with their left hand for left-pointing arrows and a different button with their right hand for right-pointing arrows. On incongruent trials, the child must suppress the default tendency to respond based on the side of the screen and instead respond based solely on the direction of the arrow. The dependent variable is the bin score derived from the rank-order binning procedure proposed by Hughes et al. (2014), creating a comprehensive score that combines both accuracy and response time (see description above). Lower scores represent better performance.

For flexible shifting, three tasks were administered: Creatures Moving, Emotion Stroop, and Shape School.

Creatures Moving is a computerized shifting task in which the child is instructed to use color cues (orange or purple) to determine responses on a 5-button box (e.g., moving their finger to the right for an orange creature and to the left for a purple creature). Animated creature cues are presented on screen, and the child is asked to press the correct button within a 1500 millisecond window, followed by a 500 millisecond interstimulus interval. Corrective feedback is given for incorrect responses to ensure that the child’s response for each trial is based on what should have been correct for the previous trial. Some trials are “shift” trials in which the correct response requires the child to move in the opposite direction as the previous trial, and some trials are “no-shift” trials that require moving in the same direction as the previous trial. The dependent variable combines accuracy and response time in a bin score derived from the rank-order binning procedure proposed by Hughes et al. (2014; see description above). In this version of the bin scoring procedure, “no-shift” trials are used in the place of congruent trials and “shift” trials are used in place of incongruent trials. Lower scores represent better performance.

The Emotion Stroop task is a computerized task adapted from studies that have used picture-based emotional Stroop tasks with children and adults (e.g. Heim-Dreger et al., 2006; Mauer & Borkenau, 2007). After completing blocks responding to the color of a house stimulus (yellow vs. purple) and then the emotion of a face stimulus (angry vs. happy), the child must flexibly respond to either the color or the emotion dimension based on the circular icons at the bottom of the screen that signal which dimension is relevant to the trial. One-third of the trials are shift trials, and two-thirds are non-shift trials. The dependent variable combines accuracy and response time in a bin score derived from the rank-order binning procedure proposed by Hughes et al. (2014; described above). Lower scores represent better performance.

In Shape School (Espy, 1997; Espy et al., 2006), the child names stimuli by either shape or color as quickly and accurately as possible, with the demands for each different task condition conveyed in a story about school activities. Stimuli are cartoon characters whose main body part is a square or a circle colored in blue or red. Some of the stimuli wear a hat (the dimension cue) whereas others are hatless. Stimuli are presented one at a time at the center of the screen on a white background. On each trial, the stimulus is visually displayed until the participant responds on a button box with four buttons (each coded for one of the response options – blue, red, square, and circle). After the child responses, the computer program then automatically advances to the next trial. The child first completes a color baseline condition. Thereafter, during a shape baseline condition (always administered after the color baseline condition), the child completes trials during which they are required to name the stimuli by shape. Finally, the child completes the switch condition, in which the hatted and hatless stimuli are interleaved, and the child has to switch between naming the hatless stimuli by color and the hatted stimuli by shape. Within the switch condition, after the starting trial, 1/3 of trials are shift trials, where the relevant dimension on the current stimulus differs from that in the previous trial, and 2/3 are no-shift trials, where the relevant dimension is the same as in the previous trial. The dependent variable combines accuracy and response time in a bin score derived from the rank-order binning procedure proposed by Hughes et al. (2014; described above). Lower scores represent better performance.

All tasks in the elementary school executive control battery demonstrated test-retest reliability, as indicated by significant and moderate associations between scores on a given task at consecutive assessment points (approximately one year apart): rs = .36 to .42 for Digit Span, .38 to .44 for Jumping Frog, .36 to .42 for Nebraska Barnyard, .37 to .42 for Go/No-Go, .37 to .42 for Stop Signal, .36 to .40 for Funny Animals, .37 to .42 for Arrows, .38 to .44 for Creatures Moving, .37to .44 for Emotion Stroop, and .37 to .43 for Shape School. Further, all tasks showed evidence of sensitivity to developmental changes, as reflected by improvements in mean scores each year from grades 1 through 4 (see Table 2). Typical internal consistency statistics, such as Cronbach’s alpha and split-half reliability, are not appropriate for the tasks in this study because these tasks do not meet the core assumptions of essential tau equivalence and unidimensionality; therefore, these statistics are not reported. This is consistent with previous literature using child executive control tasks, in which internal consistency statistics are generally not reported, including in recent developmental studies in elementary school (e.g., Deer, Hastings, & Hostinar, 2020; Park, Weismer, & Kaushanskaya, 2018; Wang & Liu, 2021).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Executive Control Tasks in Elementary School

| Tasks | N |

M (SD) |

Range | Skewness/ Kurtosis |

N |

M (SD) |

Range | Skewness/ Kurtosis |

N |

M (SD) |

Range | Skewness/ Kurtosis |

N |

M (SD) |

Range | Skewness/ Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digit Span Backwards (DS) | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | ||||||||||||

| 217 | 5.12 (1.39) | 0-9 | −.40/1.21 | 260 | 5.62 (1.43) | 1-12 | .03/1.55 | 271 | 6.05 (1.55) | 2-14 | .55/2.25 | 252 | 6.28 (1.69) | 0-13 | .03/1.56 | |

| Jumping Frog (FRG) | 217 | 6.13 (2.35) | 0-15 | .03/.33 | 259 | 7.33 (2.63) | 0-18 | .17/.85 | 270 | 8.57 (2.55) | 2-18 | .31/.59 | 251 | 9.54 (2.73) | 2-17 | .12/−.18 |

| Noisy Book (NB) | 217 | 11.74 (2.07) | 5.67-18 | −.02/.25 | 260 | 12.35 (1.99) | 6.67-18 | .03/.32 | 271 | 13.08 (2.22) | 7-20 | .13/.07 | 252 | 13.73 (2.21) | 8-21 | .04/−.02 |

| Arrows (ARW) | 217 | 221.20 (134.46) | 77-400 | .42/−.55 | 260 | 189.62 (65.06) | 69-381 | .69/.04 | 271 | 165.41 (56.20) | 73-341 | 1.01/.60 | 252 | 154.06 (49.22) | 73-373 | 1.16/1.94 |

| Funny Animals (FA) | 217 | 134.46 (30.83) | 72-229 | .67/.52 | 258 | 130.76 (28.31) | 10-205 | −.11/.73 | 268 | 127.79 (22.17) | 70-192 | .29/.21 | 250 | 126.39 (25.16) | 40-221 | .28/1.43 |

| Go/No-Go (GNG) | 218 | 2.38 (.65) | 0-3.12 | −.68/−.05 | 260 | 2.67 (.53) | .98-3.12 | −1.09/.44 | 271 | 2.90 (.36) | 1.11-3.12 | −1.80/3.49 | 252 | 2.93 (.32) | 1.57-3.12 | −1.73/2.46 |

| Stop Signal (STP) | 218 | .61 (.09) | .20-.90 | −.81/2.32 | 260 | .61 (.08) | .25-.85 | −.61/2.37 | 271 | .62 (.08) | .35-1 | .45/1.85 | 252 | .64 (.08) | .35-1 | .20/1.48 |

| Creatures (CRT) | 217 | 221.35 (74.99) | 73-420 | .44/−.13 | 259 | 183.84 (63.44) | 62-401 | .54/.15 | 270 | 168.99 (52.90) | 74-349 | .56/.09 | 251 | 158.49 (48.97) | 63-322 | .49/.03 |

| Emotion Stroop (EMO) | 216 | 83.40 (24.28) | 35-153 | .35/−.29 | 259 | 77.52 (24.94) | 15-164 | .68/.83 | 270 | 73.68 (23.40) | 17-152 | .52/.10 | 251 | 68.80 (19.71) | 30-140 | .46/.02 |

| Shape School – Switching (SSS) | 217 | 172.02 (44.43) | 57-306 | .48/.14 | 260 | 162.72 (43.76) | 65-364 | .90/2.02 | 271 | 155.35 (41.36) | 56-317 | .72/1.49 | 252 | 153.65 (39.54) | 63-311 | .71/1.22 |

Note. For DS, FRG, NB, GNG, STP, higher scores indicate better performance. For FA, ARW, CRT, EMO, and SSS, lower scores indicate better performance.

Elementary School General Cognitive Abilities.

Child general cognitive abilities were assessed at the first assessment point in the elementary school phase using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI; Wechsler, 1999). This brief standardized test consists of four subtests (Vocabulary, Block Design, Similarities, and Matrix Reasoning), which combine to produce a norm-referenced Full Scale IQ score representing broad cognitive abilities. Due to the lagged cohort sequential design, the majority of the participants (75%) completed the WASI in grade 1, with smaller numbers completing the WASI in grade 2 (17%), grade 3 (6%) or grade 4 (2%). In the current sample, the mean score on the WASI was 101.51 (SD=12.15).

Preschool Executive Control.

Child executive control abilities in preschool were assessed using a battery of nine neuropsychological tasks that were administered to each child during individual testing sessions in the laboratory at age 4.5 years. Tasks were specifically designed to provide developmentally-appropriate measures covering the major executive control components. Tests of working memory included Nebraska Barnyard (adapted from Noisy Book; Hughes, Dunn, & White, 1998), Nine Boxes (adapted from Diamond et al., 1997), and Delayed Alternation (Espy et al., 1999; Goldman et al., 1971). Tasks assessing inhibitory control included Big-Little Stroop (adapted from Kochanska et al., 2000), Go/No-Go (adapted from Simpson & Riggs, 2006), Shape School - Inhibit Condition (Espy, 1997; Espy et al., 2006), and a modified Snack Delay task (adapted from Kochanska et al., 1996; Korkman et al., 1998). Finally, flexible shifting was assessed using Shape School - Switching Condition (Espy, 1997; Espy et al., 2006) and Trails - Switching Condition (modified from Espy & Cwik, 2004). See Table 1 for descriptions of each preschool executive control task. The tasks have previously undergone extensive psychometric evaluation and demonstrated strong inter-rater reliability (where applicable) and good variability in a preschool sample [see James et al. (2016) for more detailed task descriptions and psychometric information]. Further, consistent with findings suggesting executive control in preschool is best represented as a unitary construct (e.g., Fuhs & Day, 2011; Willoughby et al., 2012), confirmatory factor analyses with this battery have found a unitary representation of executive control, with all 9 tasks loading on a single latent executive control factor, to provide the most parsimonious structure for modeling executive control in preschool (Espy, 2016; Nelson et al., 2016). This unitary factor representation was retained in the current study.

Table 1.

Task Descriptions and Descriptive Statistics for Preschool Executive Control

| EC Task | Brief Description | N | M (SD) | Range | Skewness/ Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working Memory | |||||

| Nebraska Barnyard (NB) | Child is presented an arrangement of squares (3x3) with animals on a screen. Pictures are then removed, and the child is given sequences of animal names and asked to select squares that correspond to locations of those sequences. The length of sequences increases across trials. | 209 | 6.89 (2.53) | 1.67 - 13 | .29/−.72 |

| Nine Boxes (9B) | Child is presented with nine boxes of varying colors and shapes and searches for a reward by choosing one in each trial. Color and shape information must be kept in mind to find rewards in fewest possible trials. For each trial, the boxes are scrambled. | 209 | 5.35 (1.83) | 2 - 9 | .37/−.83 |

| Delayed Alternation (DA) | Child is presented with two locations on a testing board and chooses between them to find a reward. The actual location of reward alternates across trials, so the last location has to be kept in mind through a delay to find the reward. | 209 | 6.13 (5.70) | −5 - 16 | .63/−.74 |

| Inhibitory Control | |||||

| Big-Little Stroop (BL) | Child is presented with drawings of a smaller object embedded within a larger object. The child is then asked to name smaller drawings. On “conflict trials,” the child needs to suppress the larger object name and say only the smaller object. | 208 | .86 (.19) | 0 - 1 | −2.41/6.94 |

| Go/No-Go (GNG) | Child is presented with a series of fish or shark stimuli. The child is told to press a button when a fish appears but to inhibit their response when a shark appears. | 209 | 2.30 (.73) | −.58 - 3.12 | −1.09/1.25 |

| Shape School - Inhibit (SSI) | Child is shown cartoon stimuli with happy or sad faces. The child is asked to name the color of cartoon when there is a happy face, but to inhibit when there is a sad face. | 208 | .95 (.13) | 0 - 1 | −4.10/21.78 |

| Modified Snack Delay (mSD) | Child presented with distraction and a tempting candy award and told to stand still until a bell rings. | 208 | 22.56 (9.33) | 0 - 45 | −.31/.23 |

| Flexible Shifting | |||||

| Shape School – Switching (SSS) | Child is presented with cartoon stimuli and asked to name the color of the cartoon when the character is not wearing a hat and say the shape when the character is wearing a hat. | 207 | .74 (.24) | 0 - 1 | −.96/.58 |

| Trails – Switching (TRB) | Child is presented a sheet of paper with pictures of dogs and bones of varying sizes. The child is asked to alternate stamping the dogs and then the bones in increasing size order. | 206 | .87 (.12) | .43 - 1 | −.95/.98 |

Preschool General Cognitive Abilities.

Child general cognitive abilities in preschool were assessed using Brief Intellectual Ability score from the Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities (WJ-III BIA; Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001), which was administered in the final session of the preschool phase (age 5.25 years for 75.17% of the sample, age 6 years for 23.13% of the sample, younger than age 5 for 1.7% of the sample). The WJ-III BIA consists of three subtests (Verbal Comprehension, Concept Formation, and Visual Matching), which combine to produce the norm-referenced BIA score as a measure of broad cognitive abilities. The mean WJ-III BIA score in the current sample was 101.63 (SD=11.89).

Analysis Plan.

The first set of analyses focused on examining the factor structure of executive control at various points in elementary school, using data from the battery of 10 executive control tasks administered each year in grades 1-4. Executive control tasks scored using the binning procedure (which results in lower scores representing better performance) were reverse scored for the analyses so that all indicator loadings would be in the same direction. Analyses compared models representing different levels and patterns of separability between executive control components, ranging from a unitary executive control construct to a highly differentiated four-factor structure with distinct working memory, response inhibition, interference suppression inhibition, and flexible shifting factors. Specifically, six models were estimated to determine the preferred structure of executive control at each grade: a) a Unitary Model; b) a two-factor model representing Working Memory and Inhibition with the shifting tasks loading on Inhibition; c) a two-factor model representing Working Memory and Inhibition with the shifting tasks loading on Working Memory; d) a three-factor model representing Working Memory, Inhibition, and Flexible Shifting; e) a three-factor model representing Working Memory, Response Inhibition, and Interference Suppression Inhibition with the shifting tasks split between the two types of Inhibition; f) a four-factor model representing Working Memory, Response Inhibition, Interference Suppression Inhibition, and Flexible Shifting. See Figure 1 for specific task loading configurations. If configural invariance held such that the same factor structure is preferred at each grade, measurement invariance tests continued to examine metric invariance (holding indicator loadings equivalent across time points to assess if the same construct is being measured over time) and scalar invariance (holding indicator intercepts equivalent across time points to assess if mean item differences are attributed only to mean differences in the latent factor).

The second set of analyses examined the associations between the previously established unitary executive control factor in preschool and the to-be-determined preferred executive control factor structure(s) found at each grade in elementary school using structural equation modeling. The preschool executive control latent factor was modeled using tasks and parameters previously found to produce good model fit with this battery in preschool (Espy, 2016; Nelson et al., 2017; Nelson et al., 2018a), with predictive paths to the executive control factor structure(s) found to best represent executive control abilities at each elementary school grade.

As a follow-up analysis, the predictive models were re-estimated controlling for preschool general cognitive abilities and elementary school general cognitive abilities, as well as the correlation between preschool and elementary school general cognitive abilities, to examine the continuity between preschool executive control and elementary school executive control, accounting for general cognitive abilities.

All models included correlated residuals for Digit Span and Jumping Frog, which were specified a priori, to account for shared methodological variance (specifically using a backward recall condition). Age at each elementary school grade assessment was included as a control variable. Age at preschool was not included as a control variable due to the minimal variability (mean age = 4.46 years, SD = .04). Instances of poor distribution measured by skewness and/or kurtosis greater than 3 or less than −3 were trimmed to three standard deviations above and below the mean. All models used Mplus 8.6 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017) and maximum likelihood – robust (MLR) estimation. Model comparison utilized the χ2 difference test for nested models and fit indices of Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) for nested and non-nested models. Hu and Bentler (1999) recommend CFI ≥ .95 and RMSEA ≤ .06 as criteria for good fit. Smaller AIC and BIC values indicate better fit. Significance testing was set at p-values less than .05.

The study was not preregistered. Study data are not available outside of the research team because the original consent process did not include authorization to share individual-level data.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Tables 1 and 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the executive control tasks at each assessment point in preschool and elementary school, respectively. Go/No-Go in third grade had poor distribution (kurtosis = 3.49) which resolved with trimming (kurtosis = 1.24). Big-Little Stroop (kurtosis = 6.94) and Shape School – Inhibit (skewness = −4.10, kurtosis = 21.78) in preschool had poor distribution which resolved or improved with trimming (Big-Little Stroop kurtosis = 4.49, Shape School – Inhibit (skewness = −2.85, kurtosis = 9.07).

Elementary School Factor Structure

Fit statistics and the χ2 likelihood difference tests examining various factor structures at each grade are shown in Table 3. The two-factor model representing Working Memory and Inhibition/Flexible Shifting (2-factor A model) fit the data significantly better than the one-factor model at all four grades, according to the χ2 likelihood difference test. The two-factor model with Working Memory and Inhibition/Flexible Shifting also fit significantly better than the alternate two-factor model with shifting tasks loading on Working Memory instead of Inhibition (the 2-factor B model), according to BIC comparison. The three-factor and four-factor models did not fit the data significantly better than the two-factor model at any grade, according to the χ2 likelihood difference test. The four-factor model at grade 1 did not converge and, therefore, was not included in the model comparison. The two-factor model with separate factors for Working Memory and Inhibition/Flexible Shifting (hereafter referred to as the “Inhibition” factor) was retained as the preferred executive control structure at grades 1-4; the final models are shown in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Fit Indices for Executive Control Measurement Models and Model Comparisons

| Grade 1 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Loglikelihood | Free Parameters | Scaling Factor | BIC | AIC | RMSEA [CI] | CFI | Δχ2a | Δ df | p | Δ BIC |

| 1-Factor | −3054.33 | 32 | 1.08 | 6280.96 | 6172.65 | .05 [.03, .08] | .87 | — | — | — | — |

| 2-Factor A | −3048.21 | 34 | 1.08 | 6279.50 | 6164.43 | .04 [.01, .07] | .92 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 11.01 | 2 | <.01 | −1.46 | |||||||

| 2-Factor B | −3052.02 | 34 | 1.09 | 6287.11 | 6172.04 | .05 [.03, .08] | .88 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 3.58 | 2 | .17 | 6.15 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | — | — | — | 7.61 | |||||||

| 3-Factor A | −3046.51 | 37 | 1.10 | 6292.25 | 6167.03 | .05 [.02, .07] | .91 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 12.39 | 5 | .03 | 11.29 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | 2.50 | 3 | .48 | 12.75 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor B | 8.86 | 3 | .03 | 5.14 | |||||||

| 3-Factor B | −3044.03 | 37 | 1.09 | 6287.29 | 6162.07 | .04 [.00, .07] | .94 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 17.95 | 5 | <01 | 6.34 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | 7.14 | 3 | .07 | 7.79 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor B | 15.18 | 3 | <01 | 0.18 | |||||||

| vs. 3-Factor A | — | — | — | −4.96 | |||||||

| 4-Factor | Model did not converge | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | |||||||||||

| 1-Factor | −3503.68 | 32 | 1.18 | 7185.31 | 7071.37 | .06 [.04, .08] | .85 | — | — | — | — |

| 2-Factor A | −3488.33 | 34 | 1.17 | 7165.72 | 7044.66 | .03 [.00, .05] | .97 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 31.37 | 2 | <01 | −19.59 | |||||||

| 2-Factor B | −3501.39 | 34 | 1.20 | 7191.85 | 7070.79 | .06 [.04, .08] | .85 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 2.81 | 2 | .25 | 6.54 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | — | — | — | 26.13 | |||||||

| 3-Factor A | −3486.85 | 37 | 1.18 | 7179.44 | 7047.70 | .03 [.00, .06] | .96 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 28.99 | 5 | <.01 | −5.86 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | 2.31 | 3 | .51 | 13.72 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor B | 34.31 | 3 | <01 | −12.41 | |||||||

| 3-Factor B | −3486.38 | 37 | 1.15 | 7178.51 | 7046.77 | .03 [.00, .05] | .97 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 34.29 | 5 | <01 | −6.80 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | 3.78 | 3 | .29 | 12.79 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor B | 50.55 | 3 | <01 | −13.34 | |||||||

| vs. 3-Factor A | — | — | — | −0.93 | |||||||

| 4-Factor | −3485.61 | 41 | 1.17 | 7199.20 | 7053.21 | .04 [.00, .06] | .95 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 31.22 | 9 | <01 | 13.89 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | 4.51 | 7 | .72 | 33.47 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor B | 30.87 | 7 | <01 | 7.35 | |||||||

| vs. 3-Factor A | 2.16 | 4 | .71 | 19.75 | |||||||

| vs. 3-Factor B | 1.16 | 4 | .89 | 20.69 | |||||||

| Grade 3 | |||||||||||

| Model | Loglikelihood | Free Parameters | Scaling Factor | BIC | AIC | RMSEA [CI] | CFI | Δχ2a | Δ df | p | Δ BIC |

| 1-Factor | −3419.90 | 32 | 1.20 | 7019.06 | 6903.79 | .03 [.00, .05] | .96 | — | — | — | — |

| 2-Factor A | −3414.62 | 34 | 1.19 | 7019.70 | 6897.23 | .00 [.00, .04] | 1.00 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 10.81 | 2 | 0.00 | 0.64 | |||||||

| 2-Factor B | −3416.48 | 34 | 1.10 | 7023.43 | 6900.96 | .02 [.00, .05] | .98 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 12.46 | 2 | 0.00 | 4.37 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | — | — | — | 3.73 | |||||||

| 3-Factor A | −3411.83 | 37 | 1.18 | 7030.94 | 6897.67 | .00 [.00, .04] | 1.00 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 15.54 | 5 | 0.01 | 11.89 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | 5.16 | 3 | 0.16 | 11.24 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor B | 4.44 | 3 | 0.22 | 7.51 | |||||||

| 3-Factor Bb | −3414.57 | 37 | 1.17 | 7036.42 | 6903.14 | .01 [.00, .05] | .99 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 10.86 | 5 | 0.05 | 17.36 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | 0.09 | 3 | 0.99 | 16.72 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor B | 1.91 | 3 | 0.59 | 12.99 | |||||||

| vs. 3-Factor A | — | — | — | 5.48 | |||||||

| 4-Factor | −3407.29 | 41 | 1.17 | 7044.27 | 6896.58 | .00 [.00, .03] | 1.00 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 24.13 | 9 | 0.00 | 25.21 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | 13.76 | 7 | 0.06 | 24.57 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor B | 12.25 | 7 | 0.09 | 20.84 | |||||||

| vs. 3-Factor A | 8.62 | 4 | 0.07 | 13.33 | |||||||

| vs. 3-Factor B | 12.94 | 4 | 0.01 | 7.85 | |||||||

| Grade 4 | |||||||||||

| 1-Factor | −3107.92 | 32 | 1.23 | 6392.77 | 6279.83 | .04 [.02,.06] | .91 | — | — | — | — |

| 2-Factor A | −3102.93 | 34 | 1.22 | 6393.87 | 6273.87 | .03 [.00,.06] | .95 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 9.65 | 2 | 0.01 | 1.10 | |||||||

| 2-Factor B | −3107.19 | 34 | 1.21 | 6402.38 | 6482.38 | .04 [.02, .07] | .90 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 1.48 | 2 | 0.48 | 9.61 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | — | — | — | 8.51 | |||||||

| 3-Factor Ab | −3101.44 | 37 | 1.20 | 6407.47 | 6276.89 | .04 [.00, .06] | .94 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 12.74 | 5 | 0.03 | 14.70 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | 2.96 | 3 | 0.40 | 13.61 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor B | 11.05 | 3 | 0.01 | 5.09 | |||||||

| 3-Factor B | −3101.21 | 37 | 1.21 | 6407.01 | 6276.42 | .04 [.00, .06] | .95 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 12.71 | 5 | 0.03 | 14.24 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | 3.22 | 3 | 0.36 | 13.14 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor B | 10.83 | 3 | 0.01 | 4.63 | |||||||

| vs. 3-Factor A | — | — | — | −0.46 | |||||||

| 4-Factor | −3098.75 | 41 | 1.20 | 6424.21 | 6279.51 | .04 [.00, .06] | .95 | — | — | — | — |

| vs. 1-Factor | 16.74 | 9 | 0.05 | 31.44 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor A | 7.52 | 7 | 0.38 | 30.34 | |||||||

| vs. 2-Factor B | 14.97 | 7 | 0.04 | 21.83 | |||||||

| vs. 3-Factor A | 4.51 | 4 | 0.34 | 16.74 | |||||||

| vs. 3-Factor B | 4.30 | 4 | 0.37 | 17.20 | |||||||

Note. BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; RMSEA = Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation; CI = confidence interval; CFI = Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index; df = degrees of freedom. Rows display model comparisons (vs. = versus). Only nested model comparisons show Δχ2 test. Nested models were compared by constraining latent parameters only. For graphical representations of the models tested, refer to Figure 1.

Δχ2 difference= 2*log likelihood difference/difference test scaling correction.

The PSI matrix is not positive definite.

1-Factor = Unitary executive control (EC) with all tasks loading onto a single factor.

2-Factor A = Two covaried latent factors: Working Memory (Digit Span Backwards, Jumping Frog, and Nebraska Barnyard) and Inhibition (Arrows, Funny Animals, Go/No-Go, Stop Signal, Creatures, Emotion Stroop, and Shape School-Switching).

2-Factor B = Two covaried latent factors: Working Memory (Digit Span Backwards, Jumping Frog, Nebraska Barnyard, Creatures, Emotion Stroop, and Shape School-Switching) and Inhibition (Arrows, Funny Animals, Go/No-Go, and Stop Signal).

3-Factor A = Three covaried latent factors: Working Memory (Digit Span Backwards, Jumping Frog, and Nebraska Barnyard), Inhibition (Arrows, Funny Animals, Go/No-Go, and Stop Signal), and Flexible Shifting (Creatures, Emotion Stroop, and Shape School-Switching).

3-Factor B = Three covaried latent factors: Working Memory (Digit Span Backwards, Jumping Frog, and Nebraska Barnyard), Response Inhibition (Go/No-Go, Stop Signal, and Creatures), and Interference Suppression Inhibition (Arrows, Funny Animals, Emotion Stroop, and Shape School-Switching).

4-Factor = Four covaried latent factors: Working Memory (Digit Span Backwards, Jumping Frog, and Nebraska Barnyard), Response Inhibition (Go/No-Go and Stop Signal), Interference Suppression (Arrows and Funny Animals), and Flexible Shifting (Creatures, Emotion Stroop, and Shape School-Shifting).

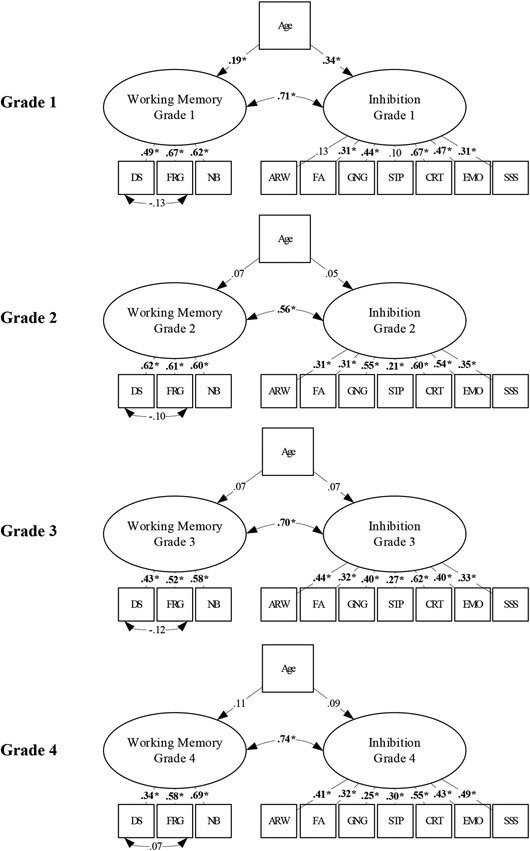

Figure 2. Preferred Two-Factor Executive Control Structure in Elementary School.

Note. Each sub-figure is a graphical representation of the preferred two-factor structure of executive control in grades 1 through 4, controlling for age at each timepoint. DS = Digit Span. FRG = Jumping Frog. NB = Nebraska Barnyard. GNG = Go/No-Go. STP = Stop Signal. FA = Funny Animals. ARW = Arrows. CRT = Creatures. EMO = Emotion Stroop. SSS = Shape School - Switching.

In the preferred two-factor model at grades 1-4, RMSEA values showed good fit (.04, .03, .00, .03, respectively) and CFI values showed acceptable to good fit (.92, .97, 1.00, .95, respectively). All 10 tasks loaded significantly onto their respective factor at each grade with the exception of Arrows and Stop Signal at grade 1. Working Memory was significantly and positively correlated with Inhibition at grade 1 (r = .71, p <.001), grade 2 (r =.56, p <.001), grade 3 (r =.70, p <.001), and grade 4 (r =.74, p <.001). Age at assessment was only a significant predictor of Working Memory (β = .19, p = .039) and Inhibition (β = 34, p <.001) at grade 1.

Longitudinal Factor Invariance

Metric and scalar measurement invariance was tested for the Working Memory and the Inhibition factors from the preferred model separately. The baseline model for each executive control component included all four grades with correlations between each grade, all item loadings and intercepts were freely estimated, and all factor means were fixed to 0 and all factor variances were fixed to 1. Correlated residual errors were allowed among the same task across the four grades.

Model fit for the baseline working memory model was good (RMSEA = .02; CFI = .99). All tasks significantly loaded onto the Working Memory latent, and the correlations among Working Memory at each grade were highly and significantly correlated (.83-.95). Metric invariance, where all factor loadings are constrained to be equal within each task at each age, passed (− 2 ΔLL(6) = 1.27, p = .97). Scalar invariance was tested constraining all item intercepts within a task to be equal across grades. The full scalar model fit significantly worse (− 2 ΔLL(6) = 14.83, p = .02) than the full metric model. Partial scalar invariance testing, conducted by freeing one intercept at a time and informed by model fit changes, revealed freeing the intercept of Nebraska Barnyard at grade 1 from being equal to grades 2-4 improved fit from the full scalar invariance model (− 2 ΔLL(1) = 6.88, p = .01) without significantly worsening model fit from the full metric invariance model (− 2 ΔLL(5) = 7.59, p = .18). This model was retained as the final measurement invariance model for Working Memory and had good fit (RMSEA = .01; CFI = 1.00).

The inhibition baseline model fit was acceptable (RMSEA = .03; CFI = .92). All tasks loaded significantly at each grade with the exception of Arrows and Stop Signal. As seen in the grade 1 structure model, Arrows and Stop Signal did not load significantly onto the Inhibition latent but did load significantly at all other grades. The correlations among Inhibition at all grades were significant and high (.77-.84). Full metric invariance, where all factor loadings are constrained within a task across all grades, fit significantly worse than the baseline model (− 2 ΔLL(18) = 39.09, p < .01). Modification indices revealed freeing the factor loading for Go/No-Go at grades 3 and 4 significantly improved model fit compared to the full metric model (− 2 ΔLL(2) = 19.03, p < .01) but did not significantly worsen model fit compared to the baseline model (− 2 ΔLL(16) = 19.71, p = .23). For all tasks but Go/No-Go at grades 3 and 4, item intercepts were constrained to be equal within a task across all grades to test scalar invariance. This initial partial scalar invariance model fit significantly worse than the partial metric invariance model (− 2 ΔLL(16) = 46.87, p < .01). Item intercepts were freed one at a time, and model fit changes were examined to further test partial scalar invariance. Freely estimating the intercepts for Arrows at grades 1 and 4, Stop Signal at grades 1 and 4, Creatures Moving at grade 2, and Emotion Stroop at grade 1 allowed for a final partial scalar invariance model that fit significantly better than the initial partial scalar invariance model (− 2 ΔLL(6) = 30.79, p < .01) and did not fit significantly worse than the partial metric invariance model (− 2 ΔLL(10) = 16.21, p = .09). The final partial measurement invariance model for Inhibition had acceptable fit (RMSEA = .03; CFI = .91).

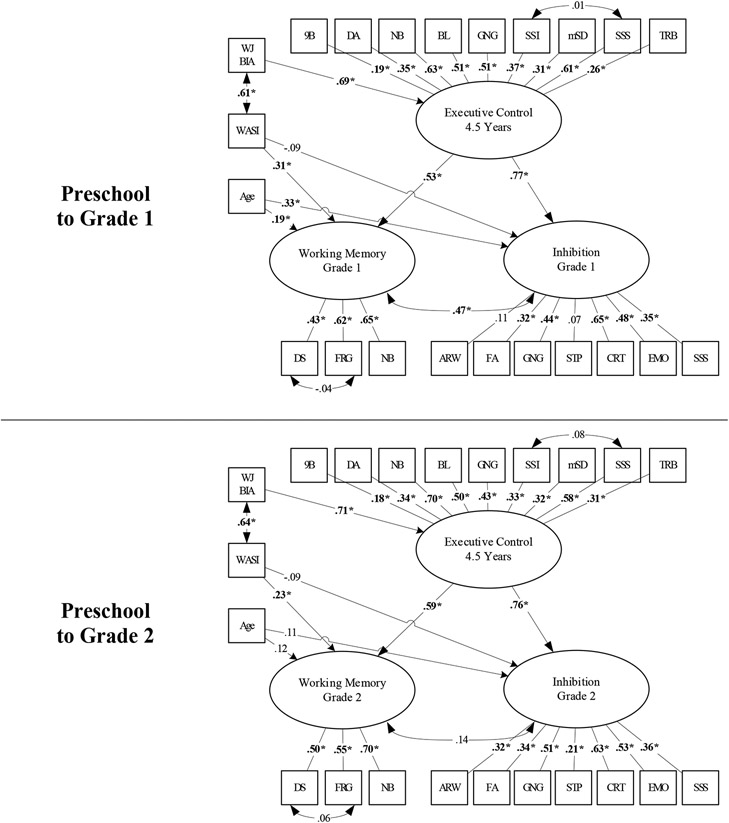

Unitary Preschool Executive Control Predicting Two-Factor Elementary School Executive Control

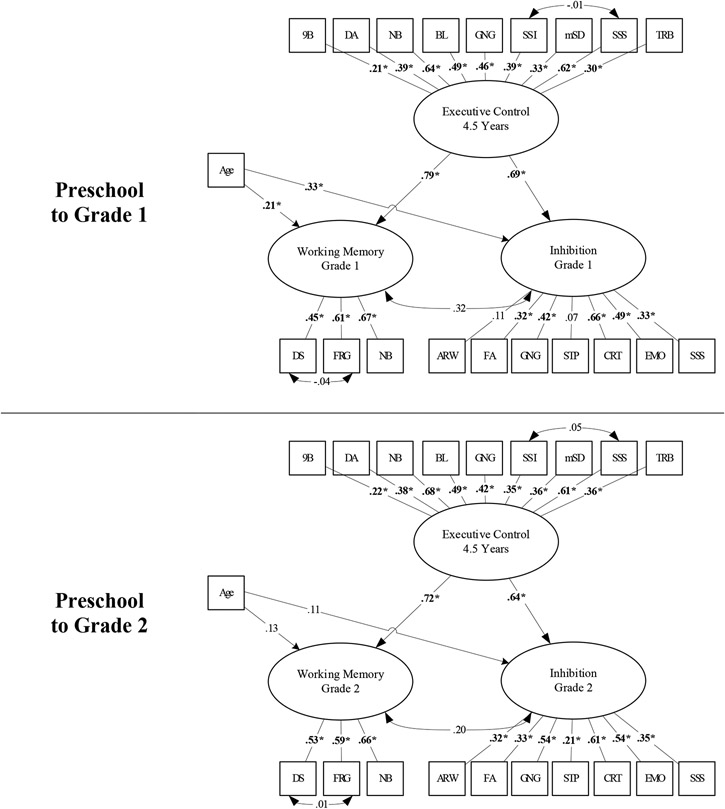

Unitary preschool executive control significantly predicted the working memory and inhibition factors from the preferred model in each grade of elementary school. Specifically, preschool executive control predicted working memory at grade 1 (β = .79, p <.001), grade 2 (β = .72, p <.001), grade 3 (β = .81, p <.001), and grade 4 (β = .66, p <.001). Preschool executive control predicted the inhibition factor at grade 1 (β = .69, p <.001), grade 2 (β = .64, p <.001), grade 3 (β = .63, p <.001), and grade 4 (β = .62, p <.001). Accounting for these relationships across time reduced the correlations among the executive control constructs in grade 1 (r = .32, p = .253), grade 2 (r = .20, p = .239), grade 3 (r = .38, p = .062), and grade 4 (r = .54, p <.001). At each grade, all tasks loaded significantly onto their respective factors, with the exception of Arrows and Stop Signal at grade 1. Age at elementary assessment significantly predicted Working Memory at grade 1 (β = .21, p = .005) and grade 4 (β = .14, p = .037), as well as Inhibition at grade 1 (β = 33, p <.001); see Figure 3.

Figure 3. Associations Between Preschool Unitary Executive Control and Elementary Working Memory and Inhibition.

Note. Each sub-figure is a graphical representation of preschool executive control (represented as a unitary latent construct) predicting elementary executive control (represented with the preferred two-factor structure) by grade; each model controls for elementary age. DS = Digit Span. FRG = Jumping Frog. NB = Nebraska Barnyard. GNG = Go/No-Go. STP = Stop Signal. FA = Funny Animals. ARW = Arrows. CRT = Creatures. EMO = Emotion Stroop. SSS = Shape School - Switching. 9B = Nine Boxes. DA = Delayed Alternation. BL = Big-Little Stroop. SSI = Shape School – Inhibit. mSD = modified Snack Delay. TRB = Trails – Switching.

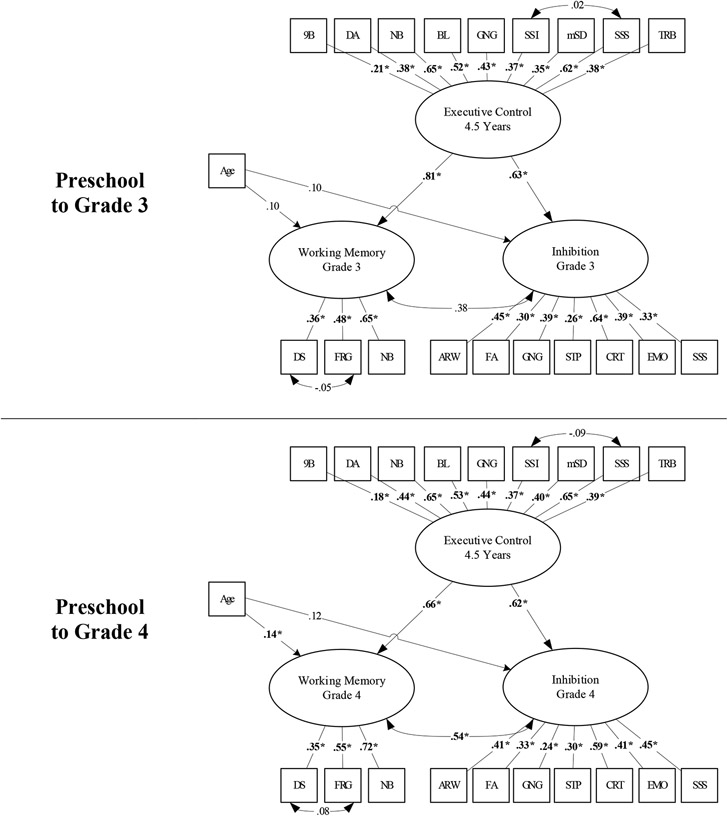

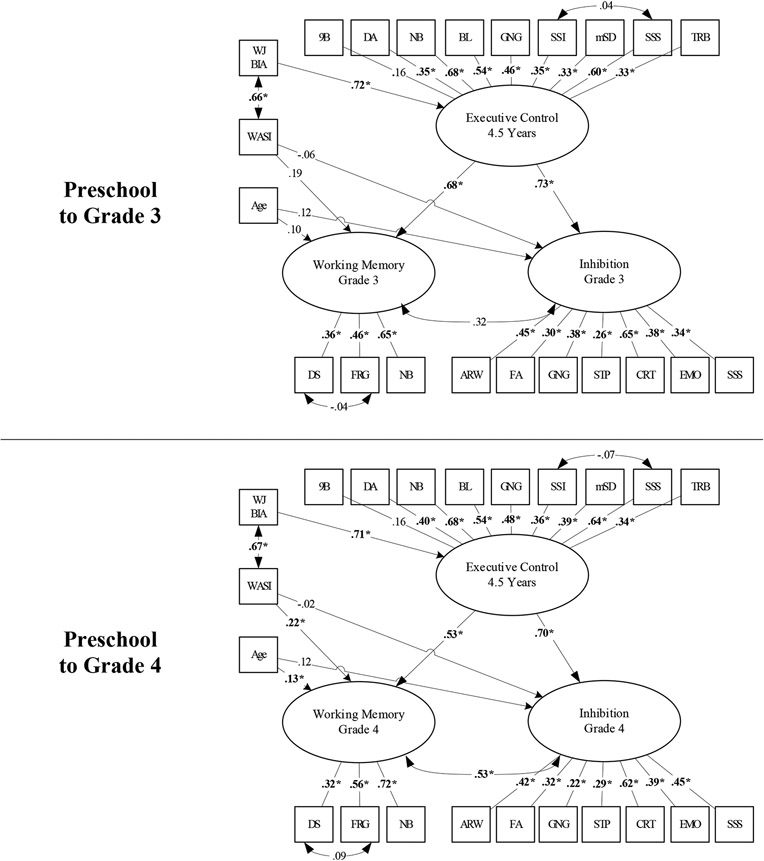

In the follow-up models, controlling for general cognitive abilities in preschool and elementary school, as well as the correlation between preschool and elementary school general cognitive abilities, unitary preschool executive control continued to significantly predict the working memory and inhibition factors in each grade of elementary school. Specifically, preschool executive control predicted working memory at grade 1 (β = .53, p <.001), grade 2 (β = .59, p <.001), grade 3 (β = .68, p <.001), and grade 4 (β = .53, p <.001). Preschool executive control predicted the inhibition factor at grade 1 (β = .77, p <.001), grade 2 (β = .16, p <.001), grade 3 (β = .73, p <.001), and grade 4 (β = .70, p <.001); see Figure 4.

Figure 4. Associations Between Preschool and Elementary School Executive Control, Controlling for General Cognitive Abilities.

Note. Each sub-figure is a graphical representation of preschool executive control (represented as a unitary latent construct) predicting elementary executive control (represented with the preferred two-factor structure) by grade; each model controls for elementary age, preschool general cognitive abilities and elementary school general cognitive abilities. DS = Digit Span. FRG = Jumping Frog. NB = Nebraska Barnyard. GNG = Go/No-Go. STP = Stop Signal. FA = Funny Animals. ARW = Arrows. CRT = Creatures. EMO = Emotion Stroop. SSS = Shape School - Switching. 9B = Nine Boxes. DA = Delayed Alternation. BL = Big- Little Stroop. SSI = Shape School – Inhibit. mSD = modified Snack Delay. TRB = Trails – Switching. WJ BIA = Woodcock-Johnson Brief Intellectual Ability. WASI = Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence.

Discussion

The current study reports several findings that replicate and extend the literature on executive control structure in childhood. Using an extensive battery of performance-based tasks, including separate tasks for each of the executive control components, this study found support for a two-factor structure throughout elementary school. Specifically, a two-factor solution with working memory and inhibition/flexible shifting factors was the preferred model for the data at grades 1-4. This finding fits well within the broader literature that has suggested a unitary executive control factor structure in preschool and a three-factor structure in adolescence and points to elementary school as a time of partial separability within the larger executive control construct. Further, these results are generally consistent with the “unity and diversity” (Friedman & Miyake, 2017; Miyake et al., 2000) conceptualization of executive control abilities as related but distinct, while adding that the degree of separability appears to increase from preschool into elementary school.

Executive Control Factor Structure in Elementary School

The pattern of separability observed in the current study also largely replicates results from previous longitudinal studies of executive control structure in elementary school (Brydges et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2013; van der Ven et al., 2013), while making important methodological improvements. The current study found evidence that working memory separates from other executive control abilities at this point in development, with less clear separation between inhibition and shifting abilities. This pattern of separability was consistent with a priori hypotheses and likely reflects an ongoing process of differentiation during elementary school in which executive control abilities are more separable than in preschool but perhaps not yet as distinct as in adolescence and adulthood. Further, although the current study found some evidence of separability between different components of executive control, the results did not support separability within inhibitory control. Given literature distinguishing response inhibition and interference suppression inhibition in adults (e.g. Friedman & Miyake, 2004), it is possible that these types of inhibitory control begin to meaningfully differentiate at some point after grade 4, although describing the exact timing remains an important question for future work.

The results also provide partial support for longitudinal measurement invariance of the factor structure across elementary school, with evidence for greater stability in working memory than in the inhibition/flexible shifting factor. This makes sense given the foundational role of working memory in executive control development and the earlier differentiation of working memory from other abilities (Diamond, 2013). Further, the relatively less stability found in the inhibition/flexible shifting factor might reflect the beginning of structural changes as this factor begins to separate into factors that become more distinct by adolescence. Research that continues to track these changes from late elementary school into adolescence – when clearer differentiation between inhibition and flexible shifting is expected – will provide further insight into this process.

Associations between Preschool Executive Control and Elementary School Executive Control

The current study also extends beyond previous literature to make particularly novel contributions in examining associations between preschool (unitary) executive control and elementary school (two-factor) executive control abilities. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore such associations using factor structures at each developmental period that were derived by rigorous factor analytic methods. Overall, the longitudinal analyses point to considerable continuity between executive control abilities across time, as evidenced by significant predictive associations between unitary preschool executive control and both executive control factors in elementary school. It is particularly noteworthy that these associations remained highly significant even after controlling for general cognitive abilities in preschool and elementary school, suggesting that the considerable continuity in executive control over time is not accounted for by the considerable continuity in general cognitive abilities. Interestingly, the associations between executive control and general cognitive abilities were much higher in preschool than in elementary school, perhaps reflecting continued differentiating between these abilities with age.

While the current study provides novel findings regarding differentiation of executive control abilities from preschool through elementary school, it does not explicitly inform our understanding of the neural mechanisms that underlie the process of differentiation throughout development. The field has gained considerable insight into the mechanisms underlying growth in executive control abilities (e.g., cognitive enrichment, parenting behaviors, poverty; Haft & Hoeft, 2017), but far less is known about the specific developmental processes in brain maturation that determine when and how executive control components differentiate. Increasing specialization of networks across childhood may offer a plausible mechanism for differentiation; as networks become more task-specific, performance on tasks that draw on different networks may increasingly diverge (Moriguchi et al., 2017). Similarly, more differential recruitment within the prefrontal cortex on executive control tasks during elementary school (Chevalier et al., 2019) could underlie emerging executive control differentiation. Clearly, more research exploring mechanisms of executive control differentiation in childhood is needed to better understand key neural changes that underlie the behavioral results reported in the current study.

Limitations