Abstract

Brain metastases (BM) are associated with significant morbidity and mortality in patients with advanced cancer. Despite significant advances in surgical, radiation, and systemic therapy in recent years, the median overall survival of patients with BM is less than 1 year. The acquisition of medical images, such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is critical for the diagnosis and stratification of patients to appropriate treatments. Radiomic analyses have the potential to improve the standard of care for patients with BM by applying artificial intelligence (AI) with already acquired medical images to predict clinical outcomes and direct the personalized care of BM patients. Herein, we outline the existing literature applying radiomics for the clinical management of BM. This includes predicting patient response to radiotherapy and identifying radiation necrosis, performing virtual biopsies to predict tumor mutation status, and determining the cancer of origin in brain tumors identified via imaging. With further development, radiomics has the potential to aid in BM patient stratification while circumventing the need for invasive tissue sampling, particularly for patients not eligible for surgical resection.

Keywords: radiomics, brain metastases, radiology, artificial intelligence

Brain Metastases: Current Approaches

Brain metastases are the most common adult brain tumor in adults, occurring in 20–40% of patients with metastatic cancer.1,2 From the time of diagnosis, patients with BM experience a median survival of less than 12 months.1,2 BM most commonly originate from primary tumors of the lung, breast, skin, kidney, and gastrointestinal system.1,3 Prognosis and therapeutic approaches are guided by several prognostic features, including performance status, the presence of extracranial metastases, type of primary cancer, tumor-mutational status in the form of molecular markers, and number and extent of BM.1,4,5 Notably, the mutation status of a tumor will often predict patient outcome and aid in treatment stratification.1 The invasion pattern of surgically resected BM and the presence of leptomeningeal lesions can also serve as relevant prognostic features.6,7

Current modalities for treating BM include surgical resection, stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT), and systemic therapies, including chemotherapy, targeted therapies, and immunotherapies.4,8-10 Surgical resection is the first-line management of large and symptomatic BM.11–13 However, surgery is often not possible for patients with extensive extracranial disease burden, multiple anatomically distant brain metastases, metastases in eloquent brain areas, and leptomeningeal involvement.14

There is a growing impetus to stratify patients with BM to novel and personalized therapies, given the high rates of postoperative recurrence,12,13,15–17 radioresistance,16 and chemo-resistance18 associated with poor overall survival. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are the modalities frequently used to visualize and diagnose tumors within the central nervous system.19

Medical imaging provides valuable information for clinicians to diagnose and subsequently manage BM. Expert analyses of images can allow for identifying lesions, tumor size, and number of metastases. Radiologists can frequently provide an informed opinion on whether a given lesion is metastatic or primary and can even predict the type of primary tumor.20 Improvements in medical image analysis technologies have begun to identify additional information within images, using novel imaging-based biomarkers that could be used to improve the accuracy of predicting clinical endpoints. It has become clear that medical images contain a plethora of quantitative, clinically relevant data that is often missed using traditional interpretation.21–24 This has led to the emergence of the field of radiomics that provides methodologies to extract additional quantitative information from images and identify features that may otherwise be too nuanced, small, or impractical to be detected by humans.25 The manner in which these quantitative analyses may help clinicians in the management of BM is thus an active area of research.

Radiomics as a Clinical Tool

Radiomic analyses involve quantifying the relationships between voxels or pixels within an image26–28 assuming that small variations in pixel/voxel intensity, position, and density can serve as prognostic and predictive biomarkers for patient stratification.29

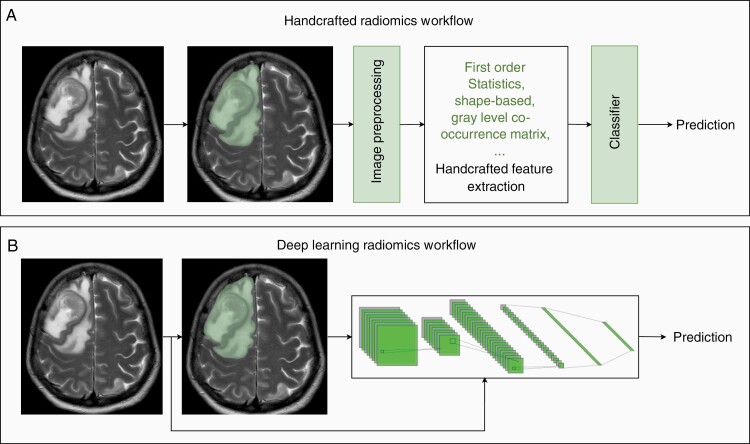

A radiomic classification pipeline can be outlined in 4 steps: (1) image acquisition, (2) image segmentation to isolate the region of interest, (3) image preprocessing, (4) feature extraction, and (5) prediction and classification of clinical outcomes by a classifier (Figure 1A and B).30,31

Figure 1.

Radiomics pipelines utilizing a T2-weighted MRI image of a patient with BM, alongside the segmentation for the image. (A) A conventional handcrafted radiomic workflow in which images acquired from patients are manually, automatically, or semi-automatically segmented/contoured to delineate regions of interest. After applying perprocessing steps, such as normalization and denoising, the outlined tumors will undergo feature extraction using mathematical features such as first-order statistics, shape-based, and gray level co-occurrence matrix. After feature extraction, a classification model could be developed to predict the outcome of interest. (B) In a DL-based radiomic workflow, features are learned by a DL model using the available data for model training. Most often, a DL model consists of two components: a deep feature extractor followed by a classifier. The deep feature extractor component most often is a convolutional neural network (CNN), and the classifier component of the model is a shallow fully connected neural network. DL-based classification models often conduct a whole-image analysis and bypass the need for tumor segmentation. However, manually, automatically, or semi-automatically acquired segmentations could also be used in a DL-based workflow.

MRI is the standard imaging modality for diagnosis and monitoring of BM, with most of the existing BM radiomics literature utilizing MR images. In addition, CT and positron emission tomography (PET) images can also be used to image BM. For MRI, such analyses can be accomplished on standard MRI—using either T1- or T2-weighted (T1/2W) images—or using quantitative imaging techniques, such as fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI), which allow for more data to be used by radiomic models for more accurate predictions.

Tumor segmentation can be achieved through manual contouring or automated segmentation to delineate areas of interest computationally. Despite its simplicity, manual contouring is tedious and time consuming. It also suffers from inter-observer and intra-observer variability.32,33 As such, automated approaches to tumor segmentation have been developed.34,35 The increased use of deep learning (DL) in radiomic pipelines means that many models will skip tumor segmentation entirely, opting for whole-image analysis instead.21 In fact, DL models can be integrated to complete tumor localization and image segmentation, feature extraction, and classification (Figure 1B).36–38 Deep convolutional neural network models have been widely used for tumor segmentation.39 U-Net architecture and its variants are among the most commonly used models for tumor segmentation.40 In fact, conventional machine learning (ML) and DL U-Net models proposed for glioma segmentation have been systematically reviewed.39 They reported that deep learning models such as U-Net have the potential for deployment in a clinical setting.

Image preprocessing is a critical step between segmentation and feature extraction. It serves to create consistency amongst images prior to radiomic analyses. There is limited research on which preprocessing steps result in the most reproducible radiomic analyses. However, studies commonly use preprocessing steps such as voxel resampling and denoising. Resampling makes voxel dimensions consistent across images from all patients in a dataset. Resampling increases the robustness of radiomic features and often aids in their generalizability across datasets.41,42 Denoising aims to remove noise, defined as randomly distributed intensities unrelated to biological features. Denoising could improve the robustness of radiomic features.42 In studies where clinical images are compared across timepoints, image registration is essential, such that anatomical structures are lined up, permitting comparison of extracted radiomic features.43 However, the type of registration algorithm used could affect the repeatability of radiomic features.43

Processed images are subjected to feature extraction, whereby the intrinsic relationships between pixels/voxels are quantified and used to derive associations with clinical outcomes. Traditionally, feature extraction relied on “handcrafted” analyses, where quantitative features are defined based on first-order statistics, shape, and texture.21 DL-based algorithms have been increasingly used for image analysis and feature extraction.21,44 During this process, several hundred to a few thousand features are extracted. Classifiers combine extracted features and occasionally other clinically relevant data (eg, age, sex, and performance status). As such, classifiers can rely on either statistical methods or artificial intelligence (AI)-based approaches to predict clinical outcomes.21 Notably, ML approaches are particularly well suited for creating such prediction models since they can learn over time to improve prediction accuracy and are more suited for handling high-dimensional features. The implementation of AI in radiomics has several distinct advantages for quantitative image analysis. The use of AI-based classification permits the analysis of numerous radiomic features on large-patient datasets. Thus, clinical decision-making is based on a radiomic-signature, rather than the isolated predictive power of a single radiomic feature. ML-based classifiers make clinical predictions based on training data sets. “Deep”-extracted features—ie features extracted by DL models—can often be much more nuanced than those found through handcrafted analysis.21

A particular challenge for classifiers in BM-specific radiomics is the inherent clustering of radiomics features due to their high correlations between these features. Notably, tumors may be segmented as sub-regions, or patients may present with several lesions, leading to multiple observations per patient. The clustering resulted from the high correlation of these features can bias estimates of classifier performance, although no standard solution to this has been presented to date.45 When developing machine learning models, it is essential to avoid distributing data points for a patient across training and test sets as such scenarios violate the independent assumption, which states that data used for model training and evaluation should be independent. It has been empirically shown that violating the independent assumption could lead to a substantial but superficial and misleading boost in model performance.46 When analyzing multiple regions of interest within the same patient, calculating patient-level performance measures could prevent the bias introduced by multiple predictions associated with these regions of interest for some patients.47 However, this approach is not always applicable since the multiple predictions in multi-region analysis, eg, analyzing several lesions within the same patient, do not always need to be consistent. For example, some lesions within a patient might be malignant and some benign. Consequently, patient-level prediction is not always medically informative or relevant. Notably, variance adjustment, logistic random-effects models, and generalized estimating equations can be applied as other statistical methods to adjust for the high correlation in clustered data when calculating sensitivity and specificity.47

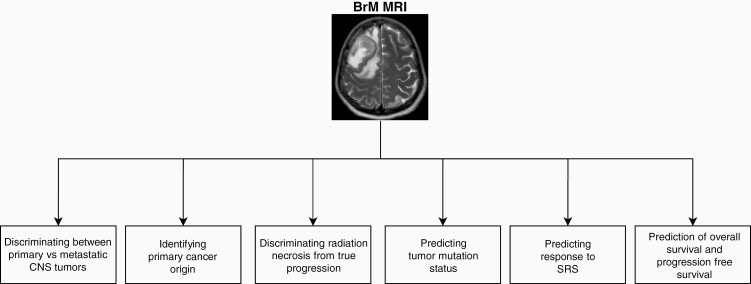

Radiomic-identified biomarkers are not always fully explainable so that the quantitative values for each feature can be understood and interpreted by humans. This issue is more profound for DL models. However, the lack of interpretability of these models does not mean that they are not generalizable or reproducible. There have been efforts to standardize radiomic-derived biomarkers identified across different groups, creating defined biomarkers that could be generalized across software from different institutions.41 The Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative (IBSI) aimed at producing and validating reference values for radiomics features enabling the verification of radiomics software to increase the reproducibility of radiomics studies and facilitate model deployment in clinical settings.41 Despite these initiatives, variation in image acquisition, reconstruction, and segmentation might still lead to a lack of generalizability in radiomics studies. In multicentric or multiscanner settings, features extracted by standardized radiomics software might lack reproducibility due to sources of variations such as different scanner types, field strengths, or acquisition protocols. The role of biomarkers in radiomics is not limited to extracting features that may predict factors such as overall survival, as radiomic analysis may lead to the efficient and noninvasive identification of known biomarkers. For instance, prediction models can often accurately determine factors such as tumor mutation status and proliferative index (KI67 immunohistochemistry status).48 Radiomic and quantitative image analysis have become increasingly relevant tools in neuro-oncology. Imaging is continually a part of patient care, and radiomic analyses exploit this existing data to provide further noninvasive predictions pertaining to patient survival, mutation status, and other factors that can help stratify patients into a novel and more personalized treatment plans (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Current applications of radiomics in brain metastases (BM) management. Radiomics has emerged as a powerful tool in the personalized management of brain metastases (BM). This includes discriminating BM from primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors, identifying the site of primary cancer of origin, discriminating radiation necrosis from recurrence, predicting tumor mutation status, and predicting patient response to stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS).

Radiomics as a Tool to Predict Response to Stereotactic Radiosurgery

SRS is the standard of care for patients with 1–4 BM, less than 3 cm in diameter.49–53 For patients with more than 4, WBRT is the current standard of care with emerging data suggesting that up to 10 BM can be successfully treated with SRS.54–56 Unfortunately, not all patients are responsive to radiation therapy, with large BM rarely experiencing prolonged clinical benefit.57–62 Predicting response to SRS is challenging, and disease progression may only be apparent through imaging several months after treatment. Using serum-based biomarkers to predict sensitivity is promising but an approach in the early phases of development.63 Radiomic tools may be able to effectively predict patient response to radiotherapy using medical images alone.

Several studies have used radiomics models to predict patient response to SRS (summarized in Table 1).64–67 In one study, contrast-enhanced (CE) T1W and T2 FLAIR alongside a support vector machine was able to predict overall response, as well as response at 6- and 12-month time points based on early images of BM.66 The group retroactively separated patients and tumors into 2 cohorts: those predicted to show local control and those predicted to show local failure following SRS treatments. Tumors and patients predicted to experience local failure demonstrated significantly lower control rates and shortened overall survival. Other groups have focused on specific radiomic features as predictive biomarkers for response to SRS. Notably, both tumor enhancement volume and zone percentage were found to act as prognostic factors for BM local control in SRS-treated patients.68,69

Table 1.

Radiomics as a Predictor of SRS Response

| Study | Imaging modality | Study size | Classification type | External Testing/validation dataset | Non-Radiomic/clinical information used? | Model performance/results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiang et al.71 | T1W, CE-T1W, T2W, T2-FLAIR.ADC, CBV, T1-MPRAGE | 137 patients | Random forest | Yes | Gender, lung cancer subtype | AUC = 0.852 |

| Gutsche et al.67 | CE-T1W, T2W, FLAIR | 150 patients | Random forest | Yes | Semantic features: contrast enhancement patterns classified as homogenous, heterogenous, or necrotic ring like | AUC = 0.74 |

| Wang et al.70 | CE-T1W | 28 patients | Logistic regression | No | Radiation dose maps | AUC = 0.82 Standard deviation = 0.09 |

| Huang et al.69 | CE-T1W | 161 patients | Consensus clustering to identify significant radiomic features | N/A | Age, Sex, EGFR mutation, KPS score, tumor location, tumor volume, prior chemotherapy, chemotherapy type | Zone percentage is associated with response to gamma-knife radiosurgery: MVCPHM- HR = 0.712, P = .022. MVCSPHM—HR = 0.699, P = .014 |

| Kawahara et al.72 | CE-T1W | 54 patients | Neural net | Yes | No | AUC = 0.87 |

| Mouraviev et al.64 | CE-T1W, T2-FLAIR | 87 patients | Random forest | No | Radiation prescription dose, ratio of the prescription dose and maximum dose for the lesion, maximum axial tumor diameter on CE-T1W, number of metastases, primary tumor site, and previous WBRT | AUC = 0.793 95% CI = 0.792–0.795 |

| Della Seta et al.68 | CE-T1W | 48 patients | N/A | N/A | No | Univariable analysis of enhanced tumor volume as predictor of SRS response: P = .005 Hazard Ratio = 0.372 95% CI = 0.186–0.744 |

| Karami et al.66 | CE-T1W, T2-FLAIR | 100 patients | Support vector machine | No | No | AUC (as estimated by 0.632 + rule) = 0.82 |

| Cha et al.73 | CT | 89 patients | CNN | Yes | No | AUC = 0.856 95% CI = 0.702–1 |

ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient, AUC: area under the curve, CBV: cerebral blood volume, CE: contrast-enhanced, CI: confidence interval, CT: computed tomography, FLAIR: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, MPRAGE: magnetization-prepared 180 ° C radio-frequency pulses and rapid gradient-echo, T1/2W: T1/2 weighted, HR: hazard ratio, MVCPHM: multivariate cox proportional hazards model, MVCSPHM: multivariate cause-specific proportional hazards model.

The information selected here illustrates the best-performing model. Model performance portrayed on testing data sets, if available.

One study predicting SRS-responsiveness incorporated a large number of clinical features, such as radiation dose, ratio of prescription dose to maximum dose for the lesion, tumor diameter, primary tumor site, number of metastases, and previous WBRT treatment with CE-T1W and T2-FLAIR images alongside a random forest-based classifier.64 Although clinical features alone performed poorly with an area under curve (AUC) value of 0.669, performance was enhanced when combining radiomic features with clinical information generating an AUC of 0.793. Similarly, another study incorporated information relating to radiation dose in BM patients treated with SRS in CE-T1W images.70 The best-performing model using logistic regression analysis incorporated features relating to dose skewness, dose entropy, and dose minimum alongside other handcrafted radiomic features.

One group compared radiomic features to CE patterns defined by three radiologists as either homogenous, heterogeneous, or necrotic ring-like from CE-T1W, T2W, and FLAIR images as predictors of patient response to SRS.67 Their best-performing model integrated both radiomic and semantic features for classification by a random forest algorithm.

Multiparametric MRI also has the potential to predict patient response to SRS treatment. Numerous MRI modalities (Table 1), coupled with features extracted from both the tumor core and peritumoral edema, were used to generate a radiomic model.71 A random forest algorithm incorporated features from several different imaging modalities, including apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and cerebral blood volume (CBV) maps, were significant for predicting patient response.71

Notably, 2 studies have included DL in their radiomic pipeline for the prediction of response to SRS.72,73 One group classified patients based on predicted response to gamma-knife radiosurgery using a 10-layered neural network from CE-T1W images.72 The model showed an accuracy of 78%; however, with a testing set of only 9 patients, the generalizability to larger data sets may be challenging. Conversely, the second group applied a DL for both feature extraction and classification on CT images of BM.73 They created “ensemble” models that consisted of 10 differently trained and validated convolutional neural networks (CNNs), resulting in their highest predictive power. Notably, CT images are used less frequently for the imaging of BM compared to MRI. Patients enrolled in the study were limited to a short 3-month follow-up. Thus treatment response did not account for pseudoprogression.

The body of literature describing radiomics-based predictions of SRS response is still developing. Future studies may focus on incorporating larger and multi-institutional data sets as models begin to become more generalizable for clinical use. Previous research in the field has shown that semantic features from contrast-enhanced MRI can act as prognostic features for SRS responsiveness.74 However, it is evident that there is a need for more biomarkers aiding in the identification of these non-responsive patients. As the radiomics field develops within this context, it will likely prove to be a useful approach for more personalized management of BM.

With the increasing prevalence of SRS use, and particularly with the addition of concomitant systemic therapies and longer patient survival, radiation necrosis has become an increasingly prevalent issue.75 Radiation necrosis is the death of parenchymal brain tissue following radiotherapy, with larger BM treated with a greater applied radiation dose being at higher risk.75 It is distinct from tumor recurrence or progression, in which radiation necrosis is not a malignant progress, despite exhibiting a high degree of overlap in symptoms and radiological appearance.75 Establishing strategies to accurately differentiate radiation necrosis from recurrence and tumor progression has the potential to significantly improve the care and quality of life of patients treated aggressively for lesions of equivocal significance.75 Notably, this could enable clinicians to halt further radiotherapy and potentially alleviate symptoms using drugs such as bevacizumab or corticosteroids.76–78

Several publications have focused on discriminating cases of radiation necrosis from local recurrence (LR) or tumor progression in BM patients (summarized in Table 2).65,79–85 This task remains very challenging for clinicians using traditional interpretations, and radiomic models will frequently outperform radiologists.65,84 Radiomics analyses can often discriminate radiation necrosis from true disease progression with AUC values generally above 0.80 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predicting Radiation Necrosis from Progression and Recurrence

| Study | Imaging modality | Study size | Classification type | External testing/validation dataset | Non-radiomic/clinical information used? | Model performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al.82 | CE-T1W, T2-FLAIR | 109 patients | Random forest | Yes | No | AUC = 0.71 95% CI = 0.51-0.91 |

| Dohm et al.80 | CE-T1W, FLAIR | 73 patients | Multivariate logistic analysis | Yes | No | Mechanistic/biophysical modeling: AUC = 0.95 95% CI = 0.94-0.97 Radiomic features: AUC = 0.77 95% CI = 0.75-0.80 |

| Cai et al.85* | FLAIR | 149 patients | Multivariable logistic analysis | Yes | Interval between radiotherapy and diagnosis of brain necrosis, interval between diagnosis of brain necrosis and treatment with bevacizumab | AUC = 0.827 95% CI = 0.691-0.962 |

| Hettal et al.84* | CE-T1W | 20 patients | Bagging algorithm | No | No | AUC = 0.83 95% CI = 0.65-1 |

| Hotta et al.79 | MET-PET | 41 patients | Radom forest | No | No | AUC = 0.98 |

| Lohmannet al.81 | FET-PET, CE-T1W | 52 patients | Multivariate logistic regression | No | No | AUC = 0.86 |

| Peng et al.65 | CE-T1W, T2-FLAIR | 66 patients | Support vector machine | No | No | AUC = 0.81 |

| Zhang et al.83 | T1W, CE-T1W, T2W, FLAIR | 84 patients | Ensemble classifier: RUSBoost | No | No | AUC = 0.73 |

AUC: area under the curve, CE: contrast-enhanced, CI: confidence interval, CT: computed tomography, FLAIR: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, FET: O-(2-[18F]-fluoroethyl)-l-tyrosine, MET: 11C-methionine, PET: positron emission tomography, T1/2W: T1/2 weighted.

The information selected here illustrates the best-performing models. Model performance portrayed on testing data sets, if available.

*The studies by Cai et al. and Hotta et al. predicted response in CNS-tumor patients with necrosis, not specific to BMs.

A recent study employed an integrated multiparametric radiomics, extracting features from combined CE-T1W and T2-FLAIR images to be classified by a random forest algorithm.82 Incorporating patients from two separate institutions and using a dedicated testing set aided their model’s potential generalizability. As such, these multiparametric approaches may show merit in future studies, aiding in clinical predictions.

The use of PET—particularly dynamic amino acid PET—has the potential to improve the ability to discriminate radiation necrosis from progression.86–89 For instance, a multivariate logistic regression-based classifier could accurately discriminate between radiation injury and true progression using combined O-(2-[18F]-fluoroethyl)-l-tyrosine (FET)-PET and MRI.81 Interestingly, prediction using strictly FET-PET features performed better than one using MRI alone. However, combining information from the 2 modalities resulted in their best-performing model with an accuracy of 89%. Additionally, 11C-methionine (MET)-PET scans have also been used to discriminate true progression from radiation necrosis.79 They did not limit their study to BM and included patients with gliomas. While the results using PET from both groups are promising, it is notable that FET and MET are not radiotracers currently used clinically for PET scans in lieu of [18F]-Fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG).90

In the context of treating radiation necrosis, some patients show no benefit with bevacizumab treatment and occasionally even display worsening.91 To address this issue, one study used a multivariable logistic analysis classifier from FLAIR image features that could predict patients with responsiveness to bevacizumab as a treatment for radiation necrosis.85 This work was not specific to only patients with BM but rather to patients with all primary and secondary central nervous system (CNS) tumors exhibiting radiation injury. Their prediction model considered abundant clinical information such as the interval between radiotherapy and diagnosis of radiation necrosis, the interval between radiation necrosis onset and bevacizumab treatment, and features extracted from FLAIR imaging. A comparison a radiomics-based multivariate logistic analysis classifier to biophysical modeling of tumor growth showed the latter to be favorable in predicting radiation injury from CE-T1W and FLAIR images.80 Biophysical modeling of lesion growth allows for patient-specific mathematical prediction of tumor growth based on clinical images.92 The inclusion of mechanistic features extracted through biophysical modeling could be incorporated alongside radiomic features to improve prediction accuracy.

Overall, the studies describing radiomic models that discriminate between radiation necrosis and true progression in patients with BM show the potential for future clinical applications.

Radiomics to Identify Brain Metastasis Mutational Status

With advances in systemic therapies often designed to target cancer-specific driver mutations, identifying genetic alterations within a patient’s tumor is of utmost importance for personalized management of BM. However, a patient’s BM can diverge substantially from their primary tumor of origin with respect to mutation status and frequently acquire or lose targetable genetic lesions.93 Performing next-generation sequencing, immunohistochemistry, and PCR-based assays on biopsies and surgical specimens from primary tumors or BM are used as the gold standards to identify tumor mutation status. With further development, radiomics has the potential to circumvent the need for invasive brain tissue sampling by acting as a virtual biopsy, particularly for those patients not eligible for surgical resection.

Applying radiomics to identify underlying tumor mutation is an emerging application within this field. This phenomenon is particularly notable in the context of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) BM where patients can exhibit several different genetic mutations or rearrangements that are treatable with targeted agents. Frequently mutated genes include EGFR, ALK, KRAS, BRAF, HER2, ROS1, and RET.94

Several studies have emerged using radiomics as a “virtual biopsy” for EGFR mutation status in lung cancer patients, showing moderate performance in the prediction of EGFR mutation status with AUC values ranging between 0.75 and 0.9595–97 (Table 3). However, small sample sizes may hurt the generalizability of certain models clinically.95–97 A study attempted to use a random forest-based classifier to predict mutation status in lung cancer patients with BM using contrast-enhanced T1-weighted and T2-FLAIR MRIs evaluating, EGFR, ALK, and KRAS mutation status.97 These studies show promise for radiomics as a tool for managing NSCLC patients exhibiting BM.

Table 3.

Radiomics as a Predictor of BM Mutation Status

| Study | Imaging modality | Study size | Cancer types and mutations | Classification type | External Testing/Validation Dataset | Non-Radiomic/Clinical information used? | Model Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn et al.95 | CE-T1W | 61 patients | Lung cancer: EGFR mutation status | Random forest | No | No | Small BrMs: AUC = 0.890 Large BrMs: AUC = 0.782 |

| Chen et al.97 | CE-T1W, T2-FLAIR | 110 patients | Lung cancer: EGFR, ALK, KRAS mutation status | Random forest | No | Additional sites of metastases, number of tumors, volume of the tumor core, edema/tumor volume ratio, gender, race and smoking history | EGFR status: AUC = 0.912 ALK status: AUC = 0.915 KRAS status: AUC = 0.985 |

| Park et al.96 | DTI, CE-T1W | 51 patients | NSCLC: EGFR mutation status | Radom forest | Yes | No | AUC = 0.765 95% CI = 0.638 – 0.889 |

| Meißner et al.102 | CE-T1W, T2W | 59 patients | Melanoma: BRAF mutation status | Support vector machine | Yes | Patient age, gender, previous systemic therapy, time from first diagnosis, number of BrMs, volume, tumor location, symptoms, and Karnofsky performance status | AUC = 0.92 |

| Shofty et al.101 | CE-T1W | 54 patients | Melanoma: BRAF mutation status | Support vector machine | No | Age, gender, metastasis size | AUC = 0.78 |

AUC: area under the curve, CE: contrast-enhanced, CI: confidence interval, CT: computed tomography, DTI: diffusion tensor imaging, NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer, SCLC: small cell lung cancer, T1/2W: T1/2 weighted.

The information selected here illustrates the best-performing models. Model performance portrayed on testing data sets, if available.

BRAF mutation status is an important biomarker for personalized management of metastatic melanoma.98–100 In one study, tumor location, shape, first-order, and second-order features from CE-T1W MRIs, alongside a support vector machine classifier were used to predict BRAF mutation status in melanoma-derived BM.101 Akin to previous studies predicting BM mutation status, this model showed an accuracy of 78%, although the study contained a limited number of samples. Another group has also published a support vector machine based classifier that could specifically predict the presence of BRAF V600E mutation in melanoma patients with BM with an accuracy of 86%.102 The classifier incorporated features from CE-T1W images, T2W images, and clinical information.

Radiomics as a tool for virtual biopsy of BM is still with very recent and emerging applications. Studies in the context of both lung and melanoma BM have shown that there is potential for future clinical use. In the context of glioblastoma and other primary brain tumors, there is a large body of work demonstrating the applicability of radiomics for determining alterations in MGMT promoter methylation103–106 and mutations in IDH,107,108 ATRX,109 TP53,108 and EGFR.110 Future models could thus target predicting multiple genetic alterations within a single lesion.

There is impetus for future studies to focus on incorporating larger and multi-institutional data sets to further illustrate the potential and generalizability of radiomics in this context. Furthermore, it remains to be seen whether radiogenomics approaches can predict individual mutations in single oncogenes with many different potential driver mutations beneficial to targeted therapies, such as BRAF.111,112

Applying Radiomics to Differentiate Between Primary Brain Tumors and BM

With MRI, solitary BM in the absence of a known primary tumor can be difficult to differentiate from primary tumors of the CNS origin,113 even though the increased use of quantitative MRI sequences has improved the accuracy of these diagnoses.114,115 Management of primary brain tumors differs substantially from that of BM, and misdiagnoses of either glioblastoma as BM or vice-versa do occur and are of significant consequence for affected patients.12,113 In this regard, multiple studies have applied radiomics to develop tools capable of differentiating patients with BM from those with primary CNS tumors (Table 4).116–122 The utility of radiomics to discern primary from metastatic brain lesions was underscored by demonstrating that two such models outperform neuroradiologists.119,123

Table 4.

Differentiation Between Primary CNS Tumors and BM

| Study | Imaging modality | Study size | Classification type | External testing/validation dataset | Non-radiomic/clinical information used? | Model performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mărginean et al.122 | CT | 36 patients | Univariate and multivariate statistical analyses | N/A | No | AUC = 0.992 95% CI = 0.903-1 |

| Bae et al.123 | T2W, CE-T1W | 166 patients in training cohort, 82 patients in validation cohort | Deep learning neural net | Yes | No | AUC = 0.956 95% CI = 0.918-0.990 |

| Dong et al.118 | T1W, T2W, CE-T1W | 120 patients | Five classifiers reach agreement: decision tree, neural network, support vector machine, k-nearest neighbor, naïve bayes | Yes | No | Accuracy = 0.77 Specificity = 1.00 |

| Ortiz-Ramon et al.116 | CE-T1W | 50 glioblastoma patients, 50 BrMs patients | Multilayer perceptron | No | No | AUC = 0.912 Standard deviation = 0.060 |

| Artzi et al.117 | CE-T1W | 439 patients | Support vector machine | Yes | Patient age, gender, and weight | AUC = 0.96 |

| Chen et al.120 | CE-T1W, T2W, T2-FLAIR | 134 patients | Distance correlation and logistic regression | Yes | No | AUC = 0.80 |

| Qian et al.119 | T1W, CE-T1W*, T2W | 412 patients | Support vector machine | Yes | No | AUC = 0.90 |

AUC: area under the curve, CE: contrast-enhanced, T1/2W: T1/2 weighted, FLAIR: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, CT: computed tomography, CI: confidence interval. The information selected here illustrates the best-performing models. Model performance portrayed on testing data sets, if available.

*Tumor segmentation was only performed on CE-T1W images in the study by Qian et al.

Current literature primarily uses handcrafted features alongside classical ML approaches.116–122 Despite this focus on more “traditional” radiomic approaches in the field, DL-based approaches show promise, as one group demonstrated increased predictive power in comparison to their ML-based classifier.123 Additionally, models discriminating between glioblastoma and BM is not limited to MRI, as other groups have used CT to similar effect.122

Several groups working on this application emphasized generalizability, through the use of PyRadiomics that is an open-source library allowing for standardized feature extraction, thus creating consistency across extracted features.118,119,123,124 Several groups also included external validation in their studies.119,123

Future radiomics models could thus serve as an important tool for clinicians attempting to distinguish between BM from primary CNS tumors. In the context of primary CNS tumors, radiomics has been applied to aid in grading gliomas125,126 and distinguishing glioblastoma from other CNS malignancies, such as primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL).127,128 These studies could soon evolve to distinguish lower-grade gliomas and PCNSL from BM.

Primary cancer site of origin is unknown in up to 15% of patients with BM, and nearly 5% of BM patients still have an unknown primary tumor type after autopsy.129 This complicates management, as systemic therapies vary mainly depending upon the site of the primary cancer.1 Biopsies coupled with pathology work-up can provide critical information regarding the primary cancer origin of BM but are rarely used in this context, given their invasiveness.130 However, the application of imaging-based approaches for diagnosing primary tumor of origin would avoid invasive tissue sampling. Radiomics has begun to be applied in this setting, with the goal of rapid and noninvasive assessment of BM origin.

Several radiomics models have been developed with the goal of distinguishing primary origin sites based on images of existing BM (Table 5).131,132 One study aimed to discriminate between BM and glioblastoma primary lesions, alongside primary tumor origin; however, only focusing on tumors from breast and lung.117 The group extracted features from CE-T1W MRIs, classifying using a support vector machine algorithm. Another group used 3-dimensional features from T1W MRIs and a random forest algorithm for discriminating between BM from lung and breast cancer (accuracy of 86%) and BM from lung cancer and melanoma (accuracy of 86%).132 However, this model performed poorly in discriminating breast and melanoma-derived BM from one another with an accuracy of 56%. This study was limited to only these three primary cancers, which may limit generalizability, particularly in cases of patients with BM originating from colorectal, renal, or other primary sites of origin.

Table 5.

Predicting Primary Cancer Origin Site

| Study | Imaging modality | Study size | Cancer types | Classification type | External testing/Validation dataset | Non-Radiomic/Clinical information used? | Model performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al133 | CE-CT | 144 patients | NSCLC subtypes: adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma | Binary logistic regression | Yes | Age and sex | AUC = 0.828 95% CI = 0.738–0.918 |

| Kniep et al131 | T1W, CE-T1W, FLAIR | 189 patients | SCLC, NSCLC, breast cancer, melanoma, gastrointestinal cancer, | Random forest | Yes | Age and sex | Discrimination of 3 cancer types: SCLC: AUC = 0.89 Breast cancer: AUC = 0.86 Melanoma: AUC = 0.83 Discrimination of 5 cancer types: SCLC: AUC = 0.76 Breast cancer: AUC = 0.78 Melanoma: AUC = 0.82 Gastrointestinal: AUC = 0.68 NSCLC: AUC = 0.64 |

| Ortiz-Ramonet al132 | T1W | 38 patients | Lung cancer, breast cancer, melanoma | Random forest | No | No | Lung vs. breast: AUC = 0.963 SD = 0.054 Lung vs. melanoma: AUC = 0.936 SD = 0.070 Breast vs. melanoma: AUC = 0.607 SD = 0.180 |

AUC: area under the curve, CE: contrast-enhanced, CI: confidence interval, CT: computed tomography, FLAIR: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer, SCLC: small cell lung cancer, T1/2W: T1/2 weighted.

The information selected here illustrates the best-performing models. Model performance portrayed on testing data sets, if available.

One study used T1W, CE-T1W, and FLAIR images alongside a random forest classifier to discriminate primary tumor of origin from BM images.131 The model accurately predicted BM originating from breast, small cell lung cancer (SCLC), and malignant melanoma. Prediction accuracy, however, was lower when for discerning patients with brain lesions originating from NSCLC and gastrointestinal cancers.

There have been efforts to use radiomics to distinguish subtypes within NSCLC BM. A binary logistic regression classifier could accurately distinguish NSCLC-originating BM as being either adenocarcinomas or squamous cell carcinomas using contrast-enhanced CT images.133

Future studies in this area would benefit from incorporating data sets for patients with “other” primary cancer types. While breast, melanoma, and lung cancers represent the most BM cases, the ability of models to recognize BM from gastrointestinal and kidney cancers, for instance, is essential for clinical applications in a primary tumor-agnostic patient population, as is seen in the real world.1 Despite this, the existing literature demonstrates that radiomics has the potential to identify primary cancer origin in BM.

The Future of Radiomics for BM Management

Despite the progress made implicating radiomic models for the management of BM, there remains ample space for future development. A large proportion of radiomics research using MRI and CNS tumors has focused on glioblastoma, which thus hints at potential applications to BM. Such possibilities include the use of radiomic models to predict overall survival, progression-free survival, and local recurrence-free survival for patients with BM. Notably, both overall and progression-free survival have been the target of radiomics models for glioblastoma patients.134 Recently, several studies have emerged predicting overall survival in patients with BM, although these have remained specific to NSCLC and melanoma primary cancer types.135–137

Advances in the past years have shown that radiomics is capable of predicting mutation status subtyping, particularly in the context of NSCLC BM. Future research could similarly focus on breast cancer BM subtyping, which can be an important factor for patient outcomes upon diagnosis of metastatic spread.138 Additionally, factors such as KI67 expression, HIF-1α status, and the presence of microvasculature are prognostic factors for BM.139,140 In the context of glioblastoma, it has been shown that radiomics can predict KI67 status suggesting that this is a possibility for BM as well.141,142

Tumor invasiveness has been shown to be an important prognostic factor for overall survival and local-recurrence free survival in the context of BM.7 Developing a radiomics-based approach that could predict invasion patterns of brain metastases may be advantageous for clinicians with the further development of this biomarker, as has been shown for histopathological growth patterns of colorectal cancer liver metastases.143 Radiomic prediction of brain invasiveness has similarly been pre-operatively demonstrated in meningioma, suggesting promise for future applications in BM.144,145

Another development pertinent to BM-specific radiomic models is the inclusion of peri-tumoral imaging. Notably, in the context of meningioma, peritumoral edema volume has shown to be an important biomarker for predicting invasiveness.145 In the context of BM management, peritumoral images have seldom been used for analysis. Notably, peritumoral regions, including both edema and tumor lesion borders, were shown to contain important information for a model predicting BM response to SRS.66 Additionally, a study in patients with single BM showed that textural analysis of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) images derived from DWI could improve clinical risk models.146

Radiomics has proven to be a promising approach for the personalized management and stratification of patients with BM. However, as this tool moves toward the clinic, there are several important considerations and limitations to consider. It is evident that radiomic models will serve as an additional tool for clinicians rather than a standalone modality for diagnostics and prognostication. Moreover, despite the inherent advantages of high-order image analysis, it is not a complete replacement for traditional semantic analyses performed by radiologists, as evident by several publications outlined in this review.64,67 Multi-dimensional data integration will be a key feature in future radiomics studies. This will expand past clinically relevant data such as patient age, sex, and primary site of origin to also include pathologic and genetic information to improve model performance. Notably, any radiomic model used in practice needs to perform consistently. Reproducibility and generalizability remain an issue within the field as current studies often focus on small, single-institution datasets. Future studies should aim to incorporate larger and cross-institutional data sets to demonstrate the large-scale merit of radiomic models in BM management. Additionally, these studies may cultivate higher-performing models by using heterogeneous data sets that contain differences in patients and image acquisition. Notably, there have been efforts to standardize image acquisition across all radiomic studies in clinical trials to increase reliability with regard to tumor detection and measurement.147 These efforts have resulted in consensus recommendations for a standardized brain tumor imaging protocol that includes “minimum standard” and “ideal” imaging protocols which include the implementation of black-blood imaging.147 Furthermore, there should be an emphasis on using standardized, open-source image analysis packages, such as PyRadiomics, to ensure reproducibility.41

In summary, we outlined the emerging use of radiomics for the personalized management of BM. Radiomics has yet to reach the forefront of clinical management for patients with BM. However, as this field continues to evolve, particularly with large multi-institutional studies, such a possibility will become closer to reality.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Reza Forghani for his review and comments on the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Alexander Nowakowski, Rosalind and Morris Goodman Cancer Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Québec, Canada.

Zubin Lahijanian, McGill University Health Centre, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, McGill University, Montreal, Québec, Canada.

Valerie Panet-Raymond, McGill University Health Centre, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, McGill University, Montreal, Québec, Canada.

Peter M Siegel, Rosalind and Morris Goodman Cancer Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Québec, Canada.

Kevin Petrecca, Montreal Neurological Institute-Hospital, McGill University, Montreal, Québec, Canada.

Farhad Maleki, Department of Computer Science, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Matthew Dankner, Rosalind and Morris Goodman Cancer Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Québec, Canada.

Funding

AN acknowledges support from the Canadian Institute of Health Research. MD acknowledges support from Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarships. This work was funded by Spark Grants on the Application of Disruptive Technologies in Cancer Prevention and Early Detection of the Canadian Cancer Society and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research—Institute of Cancer Research and Brain Canada Foundation (CCS grant #707078/CIHR grant #707078). This Project has been made possible with the financial support of Health Canada, through the Canada Brain Research Fund, an innovative partnership between the Government of Canada (through Health Canada) and Brain Canada, and of the Canadian Cancer Society.

Conflicts of interest statement

No conflicts to declare.

Authorship statement

All authors contributed to writing and reviewing this manuscript.

References

- 1. Achrol AS, Rennert RC, Anders C, et al. Brain metastases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Soffietti R, Rudā R, Mutani R. Management of brain metastases. J Neurol. 2002;249(10):1357–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sperduto PW, Mesko S, Li J, et al. Survival in patients with brain metastases: summary report on the updated diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment and definition of the eligibility quotient. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(32):3773–3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Suh JH, Kotecha R, Chao ST, et al. Current approaches to the management of brain metastases. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(5):279–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gaspar L, Scott C, Rotman M, et al. Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) of prognostic factors in three radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) brain metastases trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37(4):745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dankner M, Lam S, Degenhard T, et al. The underlying biology a nd therapeutic vulnerabilities of leptomeningeal metastases in adult solid cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(4):732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dankner M, Caron M, Al-Saadi T, et al. Invasive growth associated with cold-inducible RNA-binding protein expression drives recurrence of surgically resected brain metastases. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(9):1470–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fecci PE, Champion CD, Hoj J, et al. The Evolving Modern Management of Brain Metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(22):6570–6580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Le Rhun E, Guckenberger M, Smits M, et al. EANO-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with brain metastasis from solid tumours. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(11):1332–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vogelbaum MA, Brown PD, Messersmith H, et al. Treatment for brain metastases: ASCO-SNO-ASTRO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2021;40(5):492–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nussbaum ES, Djalilian HR, Cho KH, Hall WA. Brain metastases: histology, multiplicity, surgery, and survival. Cancer. 1996;78(8):1781–1788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Walsh JW, et al. A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(8):494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280(17):1485–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bindal RK, Sawaya R, Leavens ME, Lee JJ. Surgical treatment of multiple brain metastases. J Neurosurg. 1993;79(2):210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown PD, Jaeckle K, Ballman KV, et al. Effect of radiosurgery alone vs radiosurgery with whole brain radiation therapy on cognitive function in patients with 1 to 3 brain metastases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(4):401–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chang EL, Selek U, HassenbuschSJ, III, et al. Outcome variation among “Radioresistant” brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(5):936–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Routman DM, Yan E, Vora S, et al. Preoperative stereotactic radiosurgery f or brain metastases. Front Neurol. 2018;9:959–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Régina A, Demeule M, Laplante A, et al. Multidrug resistance in brain tumors: roles of the blood–brain barrier. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2001;20(1):13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fink KR, Fink JR. Imaging of brain metastases. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4(Suppl 4):S209–S219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zakaria R, Das K, Bhojak M, et al. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the management of brain metastases: diagnosis to prognosis. Cancer Imaging. 2014;14(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Forghani R. Precision digital oncology: emerging role of radiomics-based biomarkers and artificial intelligence for advanced imaging and characterization of brain tumors. Radiol Imaging Cancer. 2020;2(4):e190047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosenkrantz AB, Mendiratta-Lala M, Bartholmai BJ, et al. Clinical utility of quantitative imaging. Acad Radiol. 2015;22(1):33–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology. 2016;278(2):563–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Davnall F, Yip CSP, Ljungqvist G, et al. Assessment of tumor heterogeneity: an emerging imaging tool for clinical practice? Insights Imaging. 2012;3(6):573–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Julesz B, Gilbert EN, Shepp LA, Frisch HL. Inability of humans to discriminate between visual textures that agree in second-order statistics—revisited. Perception. 1973;2(4):391–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Castellano G, Bonilha L, Li LM, Cendes F. Texture analysis of medical images. Clin Radiol. 2004;59(12):1061–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karu K, Jain AK, Bolle RM. Is there any texture in the image? Pattern Recognit. 1996;29(9):1437–1446. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tourassi GD. Journey toward computer-aided diagnosis: role of image texture analysis. Radiology. 1999;213(2):317–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ganeshan B, Miles KA. Quantifying tumour heterogeneity with CT. Cancer Imaging. 2013;13(1):140–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kumar V, Gu Y, Basu S, et al. Radiomics: the process and the challenges. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30(9):1234–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lambin P, Rios-Velazquez E, Leijenaar R, et al. Radiomics: extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(4):441–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Dam IE, van Sörnsen de Koste JR, Hanna GG, Muirhead R, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Improving target delineation on 4-dimensional CT scans in stage I NSCLC using a deformable registration tool. Radiother Oncol. 2010;96(1):67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rios Velazquez E, Aerts HJWL, Gu Y, et al. A semiautomatic CT-based ensemble segmentation of lung tumors: comparison with oncologists’ delineations and with the surgical specimen. Radiother Oncol. 2012;105(2):167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang RY, Bi WL, Griffith B, et al. International consortium on meningiomas. Imaging and diagnostic advances for intracranial meningiomas. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21(Suppl 1):i44–i61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kickingereder P, Isensee F, Tursunova I, et al. Automated quantitative tumour response assessment of MRI in neuro-oncology with artificial neural networks: a multicentre, retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(5):728–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Laukamp KR, Thiele F, Shakirin G, et al. Fully automated detection and segmentation of meningiomas using deep learning on routine multiparametric MRI. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(1):124–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lin Y-C, Lin C-H, Lu H-Y, et al. Deep learning for fully automated tumor segmentation and extraction of magnetic resonance radiomics features in cervical cancer. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(3):1297–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yogananda CGB, Shah BR, Vejdani-Jahromi M, et al. A fully automated deep learning network for brain tumor segmentation. Tomography. 2020;6(2):186–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tillmanns N, Lum AE, Cassinelli G, et al. Identifying clinically applicable machine learning algorithms for glioma segmentation: recent a dvances and discoveries. Neurooncol Adv. 2022;4(1):vdac093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. (2015). U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In: Navab N, Hornegger J, Wells W, Frangi A. (eds) Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015. MICCAI 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 9351. Springer, Cham. 10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zwanenburg A, Vallières M, Abdalah MA, et al. The image biomarker standardization initiative: standardized quantitative radiomics for high-throughput image-based phenotyping. Radiology. 2020;295(2):328–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. van Timmeren JE, Cester D, Tanadini-Lang S, Alkadhi H, Baessler B. Radiomics in medical imaging—“how-to” guide and critical reflection. Insights Imaging 2020;11(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shiri I, Hajianfar G, Sohrabi A, et al. Repeatability of radiomic features in magnetic resonance imaging of glioblastoma: test–retest and image registration analyses. Med Phys. 2020;47(9):4265–4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Forghani R, Savadjiev P, Chatterjee A, et al. Radiomics and artificial intelligence for biomarker and prediction model development in oncology. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2019;17:995–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Park JE, Park SY, Kim HJ, Kim HS. Reproducibility and generalizability in radiomics modeling: possible strategies in radiologic and statistical perspectives. Korean J Radiol. 2019;20(7):1124–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maleki F, Ovens K, Gupta R, et al. Generalizability of machine learning models: quantitative evaluation of three methodological pitfalls. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.01337. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Genders TSS, Spronk S, Stijnen T, et al. Methods for calculating sensitivity and specificity of clustered data: a tutorial. Radiology. 2012;265(3):910–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. La Greca Saint-Esteven A, Vuong D, Tschanz F, et al. Systematic review on the association of radiomics with tumor biological endpoints. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(12):3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kocher M, Soffietti R, Abacioglu U, et al. Adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy versus observation after radiosurgery or surgical resection of one to three cerebral metastases: results of the EORTC 22952-26001 study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(2):134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Andrews DW, Scott CB, Sperduto PW, et al. Whole brain radiation therapy with or without stereotactic radiosurgery boost for patients with one to three brain metastases: phase III results of the RTOG 9508 randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9422):1665–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Aoyama H, Shirato H, Tago M, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery plus whole-brain radiation therapy vs stereotactic radiosurgery alone for treatment of brain metastases: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(21):2483–2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Soon YY, Tham IW, Lim KH, Koh WY, Lu JJ. Surgery or radiosurgery plus whole brain radiotherapy versus surgery or radiosurgery alone for brain metastases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(3):Cd009454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chang EL, Wefel JS, Hess KR, et al. Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(11):1037–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yamamoto M, Serizawa T, Shuto T, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with multiple brain metastases (JLGK0901): a multi-institutional prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(4):387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yamamoto M, Serizawa T, Higuchi Y, et al. A multi-institutional prospective observational study of stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with multiple brain metastases (JLGK0901 study update): irradiation-related complications and long-term maintenance of mini-mental state examination scores. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;99(1):31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kim GJ, Buckley ED, Herndon J, et al. outcomes in patients with 4-10 brain metastases treated with dose-adapted single-isocenter multitarget stereotactic radiosurgery: a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108(3):e727–e728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Minniti G, Scaringi C, Paolini S, et al. Single-fraction versus multifraction (3 × 9 Gy) stereotactic radiosurgery for large (>2 cm) brain metastases: a comparative analysis of local control and risk of radiation-induced brain necrosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;95(4):1142–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chao ST, De Salles A, Hayashi M, et al. stereotactic radiosurgery in the management of limited (1-4) brain metasteses: systematic review and international stereotactic radiosurgery society practice guideline. Neurosurgery. 2017;83(3):345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Eaton BR, Gebhardt B, Prabhu R, et al. Hypofractionated radiosurgery for intact or resected brain metastases: defining the optimal dose and fractionation. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lockney NA, Wang DG, Gutin PH, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with limited brain metastases treated with hypofractionated (5 × 6Gy) conformal radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2017;123(2):203–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Croker J, Chua B, Bernard A, Allon M, Foote M. Treatment of brain oligometastases with hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy utilising volumetric modulated arc therapy. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2016;33(2):125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nagai A, Shibamoto Y, Yoshida M, Wakamatsu K, Kikuchi Y. Treatment of single or multiple brain metastases by hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy using helical tomotherapy. Int J Mol Sci . 2014;15(4):6910–6924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Monteiro C, Miarka L, Perea-García M, et al. Stratification of radiosensitive brain metastases based on an actionable S100A9/RAGE resistance mechanism. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):752–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mouraviev A, Detsky J, Sahgal A, et al. Use of radiomics for the prediction of local control of brain metastases after stereotactic radiosurgery. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(6):797–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Peng L, Parekh V, Huang P, et al. distinguishing true progression from radionecrosis after stereotactic radiation therapy for brain metastases with machine learning and radiomics. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;102(4):1236–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Karami E, Soliman H, Ruschin M, et al. Quantitative MRI biomarkers of stereotactic radiotherapy outcome in brain metastasis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gutsche R, Lohmann P, Hoevels M, et al. Radiomics outperforms semantic features for prediction of response to stereotactic radiosurgery in brain metastases. Radiother Oncol. 2022;166:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Della Seta M, Collettini F, Chapiro J, et al. A 3D quantitative imaging biomarker in pre-treatment MRI predicts overall survival after stereotactic radiation therapy of patients with a singular brain metastasis. Acta Radiologica. 2019;60(11):1496–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Huang C-Y, Lee C-C, Yang H-C, et al. Radiomics as prognostic factor in brain metastases treated with Gamma Knife radiosurgery. J Neurooncol. 2020;146(3):439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wang H, Xue J, Qu T, et al. Predicting local failure of brain metastases after stereotactic radiosurgery with radiomics on planning MR images and dose maps. Med Phys. 2021;48(9):5522–5530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jiang Z, Wang B, Han X, et al. Multimodality MRI-based radiomics approach to predict the posttreatment response of lung cancer brain metastases to gamma knife radiosurgery. Eur Radiol. 2022;32(4):2266–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kawahara D, Tang X, Lee CK, Nagata Y, Watanabe Y. Predicting the local response of metastatic brain tumor to gamma knife radiosurgery by radiomics with a machine learning method. Front Oncol. 2021;10:569461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Cha YJ, Jang WI, Kim M-S, et al. Prediction of response to stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases using convolutional neural networks. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(9):5437–5445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Goodman KA, Sneed PK, McDermott MW, et al. Relationship between pattern of enhancement and local control of brain metastases after radiosurgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(1):139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Vellayappan B, Tan CL, Yong C, et al. Diagnosis and management of radiation necrosis in patients with brain metastases. Front Oncol. 2018;8:395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Chua MLK, Chua KLM, Wee JTS. Coming of age of bevacizumab in the management of radiation-induced cerebral necrosis. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(7):155–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lee AWM, Ho JHC, Tse VKC, et al. Clinical diagnosis of late temporal lobe necrosis following radiation therapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 1988;61(8):1535–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Siu A, Wind JJ, Iorgulescu JB, et al. Radiation necrosis following treatment of high grade glioma—a review of the literature and current understanding. Acta Neurochir. 2012;154(2):191–201; discussion 201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hotta M, Minamimoto R, Miwa K. 11C-methionine-PET for differentiating recurrent brain tumor from radiation necrosis: radiomics approach with random forest classifier. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):15666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Dohm AE, Nickles TM, Miller CE, et al. Clinical assessment of a biophysical model for distinguishing tumor progression from radiation necrosis. Med Phys. 2021;48(7):3852–3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lohmann P, Kocher M, Ceccon G, et al. Combined FET PET/MRI radiomics differentiates radiation injury from recurrent brain metastasis. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;20:537–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Chen X, Parekh VS, Peng L, et al. Multiparametric radiomic tissue signature and machine learning for distinguishing radiation necrosis from tumor progression after stereotactic radiosurgery. Neurooncol Adv. 2021;3(1):vdab150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zhang Z, Yang J, Ho A, et al. A predictive model for distinguishing radiation necrosis from tumour progression after gamma knife radiosurgery based on radiomic features from MR images. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(6):2255–2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hettal L, Stefani A, Salleron J, Courrech Florent, Behm-Ansmant Isabelle, Constans Jean Marc, Gauchotte Guillaume, Vogin Guillaume. Radiomics method for the differential diagnosis of radionecrosis versus progression after fractionated stereotactic body radiotherapy for brain oligometastasis. Radiat Res. 2020; 193(5):471–480, 410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Cai J, Zheng J, Shen J, et al. A radiomics model for predicting the response to bevacizumab in brain necrosis after radiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(20):5438–5447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ceccon G, Lohmann P, Stoffels G, et al. Dynamic O-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine positron emission tomography differentiates brain metastasis recurrence from radiation injury after radiotherapy. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(2):281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Galldiks N, Stoffels G, Filss CP, et al. Role of O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET for differentiation of local recurrent brain metastasis from radiation necrosis. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(9):1367–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Lizarraga KJ, Allen-Auerbach M, Czernin J, et al. (18)F-FDOPA PET for differentiating recurrent or progressive brain metastatic tumors from late or delayed radiation injury after radiation treatment. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(1):30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Cicone F, Minniti G, Romano A, et al. Accuracy of F-DOPA PET and perfusion-MRI for differentiating radionecrotic from progressive brain metastases after radiosurgery. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42(1):103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Galldiks N, Langen K-J, Albert NL, et al. PET imaging in patients with brain metastasis-report of the RANO/PET group. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21(5):585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Jeyaretna DS, Curry WT, Batchelor TT, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Plotkin SR. Exacerbation of cerebral radiation necrosis by bevacizumab. J Clin Oncol. 2010;29(7):e159–e162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Mang A, Bakas S, Subramanian S, Davatzikos C, Biros G. Integrated biophysical modeling and image analysis: application to neuro-oncology. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2020;22(1):309–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Brastianos PK, Carter SL, Santagata S, et al. Genomic characterization of brain metastases reveals branched evolution and potential therapeutic targets. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(11):1164–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Zappa C, Mousa SA. Non-small cell lung cancer: current treatment and future advances. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5(3):288–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Ahn SJ, Kwon H, Yang J-J, et al. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image radiomics of brain metastases may predict EGFR mutation status in primary lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Park YW, An C, Lee J, et al. Diffusion tensor and postcontrast T1-weighted imaging radiomics to differentiate the epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status of brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer. Neuroradiology. 2021;63(3):343–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Chen BT, Jin T, Ye N, et al. Radiomic prediction of mutation status based on MR imaging of lung cancer brain metastases. Magn Reson Imaging. 2020;69:49–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(18):1694–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dréno B, et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1867–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2014;372(1):30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Shofty B, Artzi M, Shtrozberg S, et al. Virtual biopsy using MRI radiomics for prediction of BRAF status in melanoma brain metastasis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):6623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Meißner A-K, Gutsche R, Galldiks N, et al. Radiomics for the noninvasive prediction of the BRAF mutation status in patients wit h melanoma brain metastases. Neuro Oncol. 2021:noab294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Tixier F, Um H, Bermudez D, et al. Preoperative MRI-radiomics features improve prediction of survival in glioblastoma patients over MGMT methylation status alone. Oncotarget. 2019;10(6):660–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Y-b X, Guo F, Z-l X, et al. Radiomics signature: A potential biomarker for the prediction of MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;47(5):1380–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Wei J, Yang G, Hao X, et al. A multi-sequence and habitat-based MRI radiomics signature for preoperative prediction of MGMT promoter methylation in astrocytomas with prognostic implication. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(2):877–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Li Z-C, Bai H, Sun Q, et al. Multiregional radiomics features from multiparametric MRI for prediction of MGMT methylation status in glioblastoma multiforme: a multicentre study. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(9):3640–3650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Yu J, Shi Z, Lian Y, et al. Noninvasive IDH1 mutation estimation based on a quantitative radiomics approach for grade II glioma. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(8):3509–3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Zhang X, Tian Q, Wang L, et al. Radiomics strategy for molecular subtype stratification of lower-grade glioma: detecting IDH and TP53 mutations based on multimodal MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;48(4):916–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Li Y, Liu X, Qian Z, et al. Genotype prediction of ATRX mutation in lower-grade gliomas using an MRI radiomics signature. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(7):2960–2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Li Y, Liu X, Xu K, et al. MRI features can predict EGFR expression in lower grade gliomas: A voxel-based radiomic analysis. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(1):356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Dankner M, Rose AAN, Rajkumar S, Siegel PM, Watson IR. Classifying BRAF alterations in cancer: new rational therapeutic strategies for actionable mutations. Oncogene. 2018;37(24):3183–3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Dankner M, Wang Y, Fazelzad R, et al. Clinical activity of mitogen-activated protein kinase–targeted therapies in patients with non–V600 BRAF-mutant tumors. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022(6):e2200107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Campos S, Davey P, Hird A, et al. Brain metastasis from an unknown primary, or primary brain tumour? A diagnostic dilemma. Curr Oncol. 2009;16(1):62–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Byrnes TJD, Barrick TR, Bell BA, Clark CA. Diffusion tensor imaging discriminates between glioblastoma and cerebral metastases in vivo. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(1):54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. El-Serougy LG, Abdel Razek AAK, Mousa AE, Eldawoody HAF, El-Morsy AE-ME. Differentiation between high-grade gliomas and metastatic brain tumors using Diffusion Tensor Imaging metrics. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2015;46(4):1099–1104. [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ortiz-Ramón R, Ruiz-España S, Mollá-Olmos E, Moratal D. Glioblastomas and brain metastases differentiation following an MRI texture analysis-based radiomics approach. Phys Medica. 2020;76:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Artzi M, Bressler I, Ben Bashat D. Differentiation between glioblastoma, brain metastasis and subtypes using radiomics analysis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;50(2):519–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Dong F, Li Q, Jiang B, et al. Differentiation of supratentorial single brain metastasis and glioblastoma by using peri-enhancing oedema region–derived radiomic features and multiple classifiers. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(5):3015–3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Qian Z, Li Y, Wang Y, et al. Differentiation of glioblastoma from solitary brain metastases using radiomic machine-learning classifiers. Cancer Lett. 2019;451:128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Chen C, Ou X, Wang J, Guo W, Ma X. Radiomics-based machine learning in differentiation between glioblastoma and metastatic brain tumors. Front Oncol. 2019;9:806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Takao H, Amemiya S, Kato S, et al. Deep-learning 2.5-dimensional single-shot detector improves the performance of automated detection of brain metastases on contrast-enhanced CT. Neuroradiology. 2022;64(8):1511–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Mărginean L, Ștefan PA, Lebovici A, et al. CT in the differentiation of gliomas from brain metastases: the radiomics analysis of the peritumoral zone. Brain Sci 2022;12(1):109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Bae S, An C, Ahn SS, et al. Robust performance of deep learning for distinguishing glioblastoma from single brain metastasis using radiomic features: model development and validation. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. van Griethuysen JJM, Fedorov A, Parmar C, et al. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017;77(21):e104–e107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Ditmer A, Zhang B, Shujaat T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI texture analysis for grading gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2018;140(3):583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Dong F, Li Q, Xu D, et al. Differentiation between pilocytic astrocytoma and glioblastoma: a decision tree model using contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging-derived quantitative radiomic features. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(8):3968–3975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Wu G, Chen Y, Wang Y, et al. Sparse representation-based radiomics for the diagnosis of brain tumors. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2018;37(4):893–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Kim Y, Cho H-h, Kim ST, et al. Radiomics features to distinguish glioblastoma from primary central nervous system lymphoma on multi-parametric MRI. Neuroradiology. 2018;60(12):1297–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Nayak L, Lee EQ, Wen PY. Epidemiology of brain metastases. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14(1):48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]