Abstract

Introduction:

This study explores the relationship between emotional support, perceived risk and mental health outcomes among health care workers, who faced high rates of burnout and mental distress since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

A cross-sectional, multicentred online survey of health care workers in the Greater Toronto Area, Ontario, Canada, during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic evaluated coping strategies, confidence in infection control, impact of previous work during the 2003 SARS outbreak and emotional support. Mental health outcomes were assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale, the Impact of Event Scale – Revised and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).

Results:

Of 3852 participants, 8.2% sought professional mental health services while 77.3% received emotional support from family, 74.0% from friends and 70.3% from colleagues. Those who felt unsupported in their work had higher odds ratios of experiencing moderate and severe symptoms of anxiety (odds ratio [OR] = 2.23; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.84–2.69), PTSD (OR = 1.88; 95% CI: 1.58–2.25) and depression (OR = 1.88; 95% CI: 1.57–2.25). Nearly 40% were afraid of telling family about the risks they were exposed to at work. Those who were able to share this information demonstrated lower risk of anxiety (OR = 0.58; 95% CI: 0.48–0.69), PTSD (OR = 0.48; 95% CI: 0.41–0.56) and depression (OR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.47–0.65).

Conclusion:

Informal sources of support, including family, friends and colleagues, play an important role in mitigating distress and should be encouraged and utilized more by health care workers.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, PTSD, depression, anxiety, support, infection control, burnout, mental health, psychological support, health care workers

Highlights

Health care workers mainly used informal sources of emotional support such as family, friends and colleagues during the current COVID-19 pandemic, with fewer seeking support from mental health professionals.

Those health care workers who felt confident about the effectiveness of infection control measures, and particularly organizational policies, reported less overall distress.

Health care workers who felt supported had reduced rates of hypnotic medication and alcohol use.

Feelings of anxiety may have affected health care workers’ ability to share information with their families about their risk of contracting COVID-19 at work.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a toll on health care workers’ physical and mental well-being.1-3 The distress observed is similar to that previously seen during outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and Ebola virus disease.4-7 Recently, many health care workers have chosen to leave their jobs, which compromises the system’s ability to provide care and prepare for any future surges of the pandemic or other health crises. Consequently, there is an urgent need to better understand the nature and scope of available supports and their ability to mitigate health care workers’ distress as the pandemic continues.8

Emotional and social support is effective in mitigating depression, anxiety and other psychological distress related to traumatic events.9,10 Support can be formal, such as instrumental and informational support from health care organizations and mental health professionals, and informal, namely the psychological support of family, friends and colleagues. During the COVID-19 pandemic, lack of perceived support has resulted in the predicted levels of poor psychological outcomes.11,12 While the stress experienced by health care workers during this pandemic has been recognized3,13,14, we need a better understanding of the optimal forms of support to address it.

Our study is descriptive and exploratory, and aims to identify the impact of emotional and instrumental support, such as infection control measures aimed at protecting health care workers.

Methods

Mental health outcomes based on measures of anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic have been detailed elsewhere.15 Styra et al.15 observed that a substantial proportion of health care workers experienced moderate or severe symptoms of PTSD (50.2%), anxiety (24.6%) and depression (31.5%). Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that non-clinical health care workers had greater odds of experiencing anxiety (OR = 1.68; 95% CI: 1.19–2.15, p= 0.01) and depressive symptoms (2.03; 1.34–3.07; p<0.001) than nurses, physicians and allied health care workers.15

Survey administration

We used a cross-sectional, multicentred, hospital-based online survey of health care workers at two tertiary and two community care hospitals in the Greater Toronto Area (Ontario, Canada) where patients with COVID-19 were treated. All personnel working at each of the four hospitals were invited via internal communications email to participate in the survey. Two reminders were sent each week over the two-week study period. This survey was adapted from one that we used during the 2003 SARS outbreak6 to evaluate health care workers’ mental health and the impact of infection control measures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data collection occurred during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Greater Toronto Area, from 14 to 28 May 2020 for two centres, from 27 May to 10 June 2020 for the third centre, and from 19 June to 3 July 2020 for the fourth centre.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained for all sites from Clinical Trials Ontario (CTO #3189) and each site’s institutional ethics review board.

Study population

All personnel working at each of the four hospitals were eligible to complete the survey. We categorized health care workers into four groups: nurses; physicians; allied health professionals (e.g. pharmacists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers); and non-clinical health care workers (e.g. administrative staff, research employees, environmental services).

Outcomes and measures

The survey included questions identifying dimensions of support, such as use of mental health resources and informal supports, for example, family, colleagues and friends. We assessed perception of personal and occupational risk and personal coping strategies as well as perception of the effectiveness of standard institutional infection prevention measures.

A number of survey questions asked health care workers about their perception of how infection control measures affected them during the COVID-19 pandemic. An example statement stated “I believe that the following measures are useful in protecting me from getting COVID-19,” with the followed choices: “screening of patients and hospital visitors at entrance”; “all health care workers wearing masks in clinical areas”; “alcohol hand rinse”; “regular hand washing”; “learning as much as I can about COVID-19”; and “adhering to protocols and recommended measures.”

An example question about support was phrased, “I have been receiving emotional support from…” with the following choices: “mental health professional”; “family”; “friends”; “colleagues”; or “I’m managing well on my own.”

Statements on the impact of COVID-19 stemming from the workplace included “I am afraid of telling my family about the risk I am exposed to” or “I feel supported because of the work that I do as a health care worker.” Health care workers who had worked during the 2003 SARS outbreak in the Greater Toronto Area were asked to self-identify to assess the impact of previous work experience during an emerging novel pathogen outbreak.

Primary mental health outcomes of symptoms of anxiety, PTSD and depression were assessed by validated self-report instruments: the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale for anxiety; the 22-item Impact of Event Scale – Revised (IES-R) for PTSD, made up of subscales on intrusion, avoidance and hyperarousal; and the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for measures of depression. In addition, we used cut-off scores to identify moderate and severe symptoms (GAD-7 = 10/1516; IES-R = 24/3317; and PHQ‑9 = 10/1518), with higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms.

Statistical analysis

We used statistical package R version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, AT) to analyze collected data. Pearson chi-square tests were used to analyze categorical variables across groups, and Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests to compare the severity of symptoms between groups. The significance level for each analysis was set at α = 0.05, and all tests were 2-tailed. Statistical significance was set at 0.001.

We used overall domain scores for each analysis (GAD-7, IES-R and PHQ-9). Mental health outcome measures were not normally distributed and are reported as medians with interquartile ranges. Imputation was only used for a small number of demographic survey items (less than 10% missing at random) that were needed to power the multivariable logistic regression analysis. Demographic and descriptive frequency tables were reported as is and did not use any imputed data. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed on previous univariable models; these were shown to be significant and were adjusted for age, gender, type of health care work, hypnotic medication use, alcohol use and work experience during the 2003 SARS outbreak in Toronto.

Results

Demographics

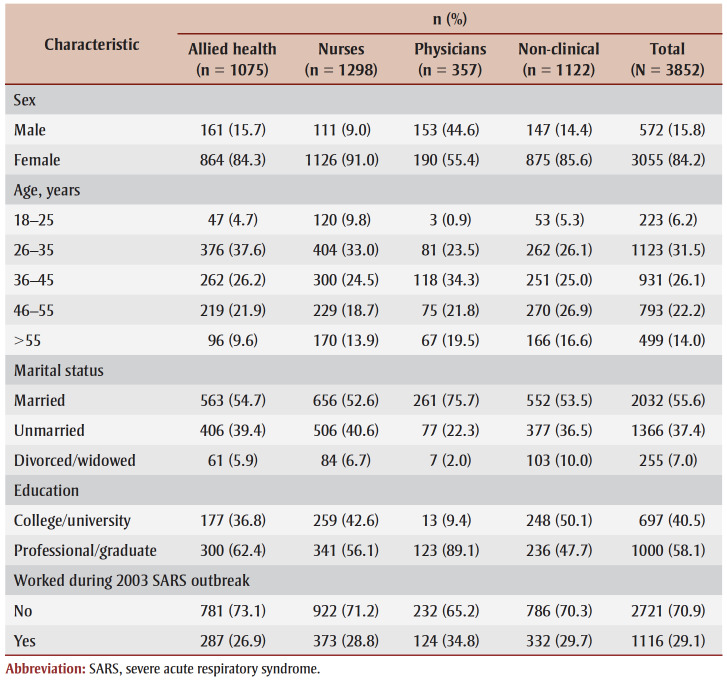

The participants who completed the survey (N = 3852) comprised nurses (n = 1298; 33.6%), non-clinical health care workers (n = 1122; 29.1%), allied health staff (n= 1075; 27.9%) and physicians (n = 357; 9.3%). The majority (84.2%) identified as female, and just over half (55.6%) were married (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and occupational characteristics of health care workers who participated in the study of mental health supports during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, May–July 2020, Greater Toronto Area, Ontario, Canada.

Emotional support

A small percentage of health care workers (8.2%; n=266) sought professional mental health support. However, the majority relied on using a number of different informal supports such as family (77.3%; n=2649), friends (74.0%; n=2496) and colleagues (70.3%; n=2347).

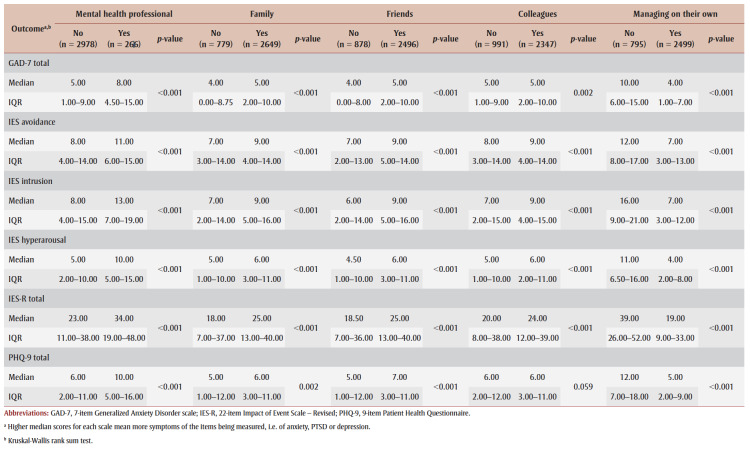

Health care workers who sought support from mental health professionals scored significantly higher on symptoms of anxiety, PTSD and depression (Table 2) than those who did not seek professional support. There were no differences in seeking professional mental health support among the different categories of health care workers. Nurses (79%; n=905) and allied health staff (71.5%; n=681) sought emotional support from colleagues more frequently than did non-clinical health care workers (60.4%; n=549) and physicians (62.5%; n=207) (p<0.001). Female health care workers sought support from family (79%; n=2248), friends (76.8%; n=2148) and colleagues (73.7%; n=2038) more frequently than did their male colleagues (p<0.001). Health care workers who had worked during the 2003 SARS outbreak (73.9%; n=719) turned to colleagues more often than those who had not been employed in the field during that time (68.9%; n=1622; p<0.004) (data not shown).

Table 2. Support from mental health professionals, family, friends or colleagues or managing on their own and participants’ GAD-7, IES-R and PHQ-9 scores during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, May–July 2020, Greater Toronto Area, Ontario, Canada.

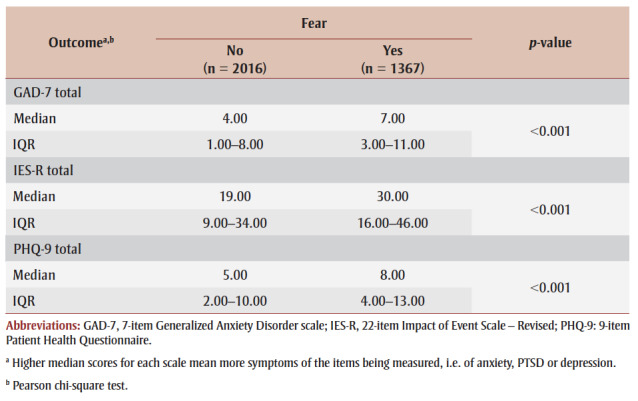

Approximately 40% of health care workers (n= 1367) reported being afraid of disclosing to family the risk they were exposed to at work, with no difference between men and women. Those who expressed an inability to discuss their risk with family had significantly higher scores on all measures of psychological distress (p<0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Association between healthcare workers’ fear of informing family of perceived risk and participants’ GAD-7, IES-R and PHQ-9 scores during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, May–July 2020, Greater Toronto Area, Ontario, Canada.

|

Health care workers’ decisions to inform their families of their risk was not influenced by whether they felt emotionally supported by the families. Physicians were more likely to share this information with their families (67.0%; n=219) than were nurses (54.6%; n=641) (p<0.001) (data not shown).

Nearly two-thirds (63.8%; n=653) of participants who had worked during the 2003 SARS outbreak felt comfortable sharing the level of risk with their families (p<0.001) versus 56.9% (n = 1424) of those who had not worked during that outbreak (data not shown).

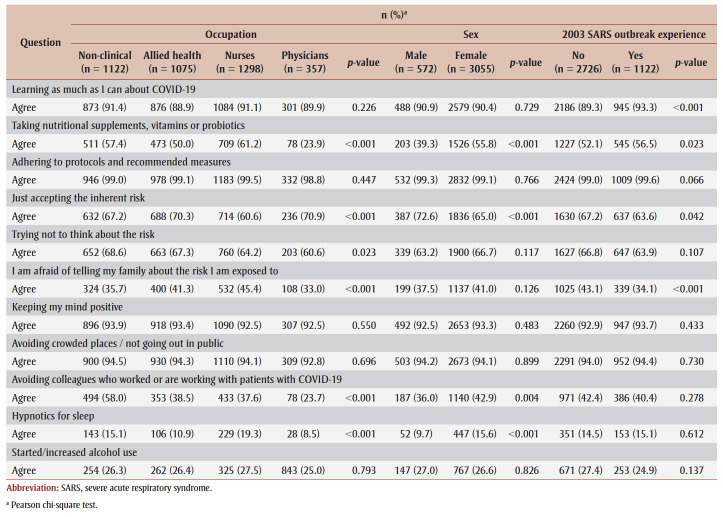

Coping strategies

Most participants (90.5%; n=3143) expressed interest in learning about COVID-19 (p<0.001). More than half reported coping by accepting their perceived risk (66.2%), by trying not to think about the risk (66%) and by keeping their minds positive (93.1%) (data not shown). There were significant differences in risk perceptions across the occupations. Higher proportions of non-clinical health care workers (58%; n=494) than other groups of health care workers avoided colleagues caring for patients with COVID-19 (Table 4).

Table 4. Participants’ coping strategies by occupation, sex and work experience during the 2003 SARS outbreak during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, May–July 2020, Greater Toronto Area, Ontario, Canada.

A small percentage of participants (10.9%; n=333) were considering other employment or resigning. As many as 15.7% (n=160) of nurses considered changing employment compared to 9.4% of non-clinical health care workers (n=78), 8.6% of allied health professionals (n=76) and 5.9% of physicians (n=19) (p<0.001) (data not shown).

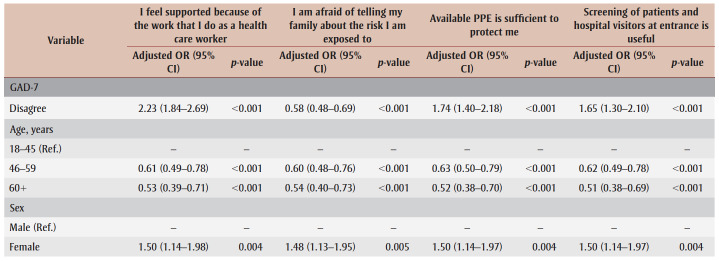

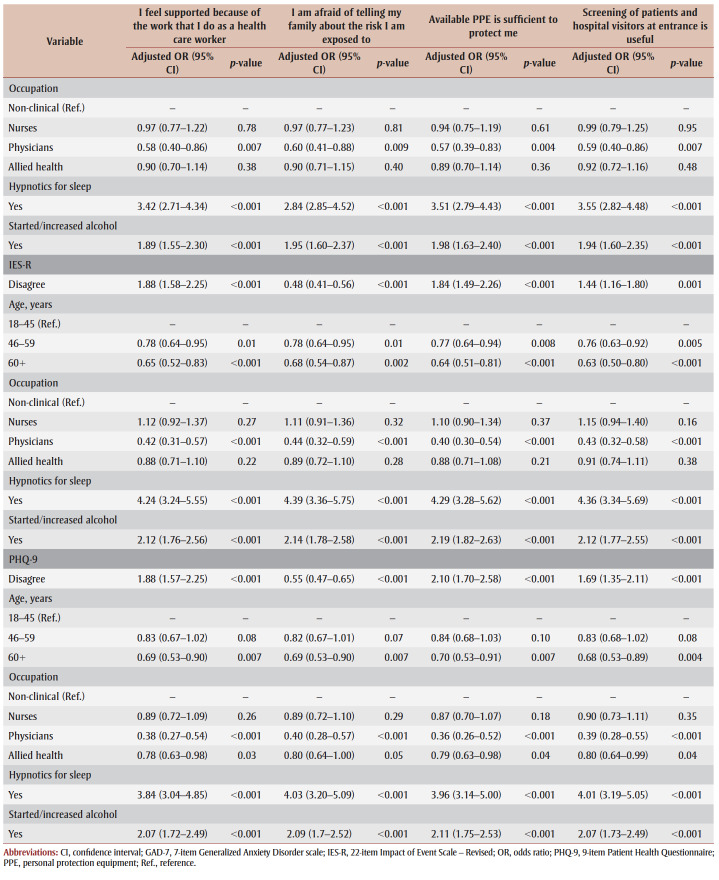

A large proportion (72.5%; n=2452) felt supported because of their work as a health care worker. Those who felt unsupported had significantly higher odds of experiencing moderate and severe symptoms of psychological distress on multivariable logistic regression analysis: anxiety (OR = 2.23; 95% CI: 1.84–2.69; p<0.001), PTSD (1.88; 1.58–2.25; p<0.001) and depression (1.88; 1.57–2.25). Health care workers who did not feel supported because of the work they do were also at an increased risk for hypnotic use and likelihood of experiencing moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety (3.42; 2.71–4.34), depression (3.84; 3.04–4.85) and PTSD (4.24; 3.24–5.55). Similarly, alcohol use and feeling unsupported were associated with moderate to severe anxiety (1.89; 1.55–2.30), PTSD symptoms (2.12; 1.76–2.56) and depression (2.07; 1.72–2.49). Health care workers who were able to tell their families about their perceived at-work risk demonstrated lower rates of moderate to severe anxiety (0.58; 0.48–0.69), symptoms of PTSD (0.48; 0.41–0.56) and symptoms of depression (0.55; 0.47–0.65) (see Table 5).

Table 5. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of support and infection control measures on participants’ moderate/severe mental health outcomes during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, May–July 2020, Greater Toronto Area, Ontario, Canada.

Infection control measures

Health care workers who did not consider the available personal protection equipment (PPE) sufficient protection were more likely to experience anxiety (OR = 1.74; 95% CI: 1.40–2.18; p<0.001), symptoms of PTSD (1.84; 1.49–2.26; p<0.001) and depression (2.10; 1.70–2.58; p<0.001) (Table 5). Participants who were not confident with the screening processes for patients and visitors at the hospital entrances also had higher rates of anxiety (1.65; 1.30–2.10; p<0.001), symptoms of PTSD (1.44; 1.16–1.80; p<0.001) and depression (1.69; 1.35–2.11; p<0.001).

In addition, those who disagreed with the adequacy of the infection control measures in place (adequate PPE and screening of patients and hospital visitors) were more likely to experience moderate to severe scores on all outcome measures (Table 5). Elevated rates of psychological distress were also observed among health care workers who disagreed with the effectiveness of routine handwashing (depression: OR = 2.67, 95% CI: 1.10–6.47, p<0.03) and alcohol hand rinse use (anxiety: OR = 1.67, 95% CI: 1.09–2.58, p<0.02; symptoms of PTSD: OR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.27–2.90, p<0.002; depression: OR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.14–2.59, p<0.01).

Discussion

Our study found that health care workers used a variety of psychological supports during the COVID-19 pandemic, with about three-quarters seeking emotional support from their families (77.3%), friends (74.0%) and colleagues (70.3%). Approximately 8% sought formal mental health support. Their use of formal mental health supports may relate to several factors: self-identification of severe psychological distress requiring intervention; pre-existing relationships with mental health supports; or prior mental health concerns that were exacerbated by social restrictions and workplace challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The overall low rate of accessing mental health supports may be a result of difficulties accessing these supports because of long work hours as well as the stigma associated with requesting or needing mental health support. Alternatively, health care workers may feel they get adequate informal support from colleagues, family and friends and only turn to the available professional mental health supports if they have greater psychological distress. Health care workers may experience more psychological distress as a result of the lack of support, and those with high psychological distress may be more likely to perceive the available support to be inadequate.

Other studies of health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic mirror our findings of the vital importance of the support of family, friends and colleagues. Family support has been shown to alleviate feelings of isolation and promote positive mental health19, whereas the lack of social support from family and friends is associated with higher levels of anxiety, symptoms of PTSD and depression11 and greater risk of burnout12. Support from colleagues has previously been shown to be associated with resilience, which is a protective factor against psychological distress.20,21 Participants who had worked during the 2003 SARS outbreak were more likely to report seeking support from colleagues. As the SARS outbreak occurred almost 20 years ago, health care workers still working through the COVID-19 pandemic may be more established in their workplaces, with a stable and extensive network of supportive colleagues. Health care workers who treated people with COVID-19 built a stronger camaraderie with colleagues as a result of their shared experience.22 This may be similar to shared experiences of working during the 2003 SARS outbreak in helping to mitigate distress.

Those health care workers who reported that they had talked about their perceived risk with family had lower scores for anxiety, PTSD and depression. It is unclear whether those who communicated their perceived risk were less anxious about the risk and therefore felt able to talk about it with family or whether talking about their risk with family made them feel less distressed because their family was now aware of their risk. Another explanation may be the communication of perceived risk to family resulted in less distress because the participants now saw themselves in the role of trying to mitigate the anxiety of family members by modelling calmness.

Although family played a role in providing support for health care workers, 36.9% (n=1367) did not talk about their perceived risk with family members. A number of factors may have played a role in this non-disclosure, including their desire to relieve their families of any concern about their own perceived risk and potential risk as well as concern that family members would respond negatively. Sharing information is a positive step towards engaging support and mitigating potential psychological distress and possible family conflict. Furthermore, while health care workers receive infection control information and education and may be provided with mental health resources by their organizations, giving their family members additional resources may be a valuable and practical intervention.

A negative perception of the protective effect of institutional infection control measures, an overall sense of a lack of support and hesitancy to discuss risk with family were all associated with use of alcohol and hypnotic medications and with a higher risk of moderate/severe symptoms of anxiety, PTSD and depression in our study. The stress of a pandemic may result in greater reliance on substances to self-medicate psychological distress and may also exacerbate previous use. Perceived social support has been found to minimize alcohol and hypnotic use, especially during stressful life events.23-25 The intertwined relationship between support, mental health and substance use26 should be considered in multifaceted interventions for health care workers, especially as they may engage in “escape-avoidance” behaviours to relieve distress5,12,27. Education and resources about healthier coping behaviours and the mental and physical effects of substance use could better assist this potentially vulnerable group.

A small percentage of those surveyed (10.9%; n=333) were considering leaving health care, a desire that has been found to be mediated by individual experiences of occupational stress, such as workplace support, sense of efficacy and ability to complete work.28 These are important factors that need to be addressed for worker retention. This study was performed relatively early during the COVID-19 pandemic, and emerging data about increasing departures29 suggest that the impact of prolonged individual experiences of workplace stress will need further investigation. These aspects of workplace stress have significant implications for organizations, and system-level changes may be necessary to ensure a sense of safety, efficacy and empowerment to facilitate staff retention during and post pandemic. Support from their organizations and society has been found to help in building satisfaction and resilience among health care workers.30 Collective support for health care workers at the beginning of the pandemic seemed universal. Support, ranging from nightly neighbourhood cheers to donated meals from local restauranteurs, served as forms of recognition that may have helped mitigate stress. Support from family and friends has also been shown to contribute to a sense of purpose and belonging with a direct impact on preventing psychological distress and fostering compliance and positive attitudes towards infection control restrictions.19

PPE is a safeguard for frontline staff during infectious diseases outbreaks and worries about PPE availability (often perceived to demonstrate lack of institutional support) has been a predictor of worse psychological outcomes.4,31,32 Our study finds that trust in organizational measures is associated with degree of psychological distress, and suggests that understanding each measure’s role in infection prevention and the rationale for changes to protocols in the face of emerging information on transmission is beneficial for health care workers. The ability to adhere to infection prevention and control protocols can promote a level of self-efficacy for personal safety31, while a consistent reliable supply of PPE provides a sense of care and support on an institutional level4,32. Our findings demonstrate that levels of trust in the protective measures implemented by the hospital—adequate PPE, visitor screening and perceived effectiveness of alcohol hand rinse—were related to symptoms of distress. Having confidence and trust in infection control measures may result in less distress; however, trying to properly follow infection control measures may increase distress, particularly when recommendations regarding which measures are needed undergo frequent changes.

During the pandemic, information has been rapidly changing, making bidirectional communication and transparency vital.33 A qualitative study of health care workers’ experiences during the pandemic found that organizational transparency helped mitigate stress and a fear of uncertainty and to navigate changing protocols and information.30 Effective strategies for daily communication are necessary to minimize misunderstandings that may heighten distress.34 Strategies for receiving and integrating feedback from frontline health care workers need to be well-defined and addressed.35 Data gaps and a lack of transparency have been found to be an ongoing issue that undermine trust in the pandemic response.36

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, in order to include physicians, nurses, allied health and non-clinical health care workers, it was necessary to use a non-targeted email link, which did not allow us to estimate the response rate. Using non-targeted email links did not allow us to track the number of health care workers who saw the email and decided not to participate.

Second, several hospitals were involved in the study, and we are unable to determine possible differences in mitigating or exacerbating factors at individual organizations. In addition, we did not enquire as to whether mental health conditions or formal mental health supports existed prior to the pandemic; knowing this would have helped assess their contributions to the psychological distress that we document.

Finally, the data were collected during the first wave of the pandemic, between 14 May and 3 July 2020 for all four centres. Reporting biases, especially during a time of high stress, may have led some to complete the survey more positively and others to complete it more negatively. A follow-up survey could provide information about longer-term coping strategies and supports that the participants may have used as well as changing perceptions of and trust in infection control measures.

Conclusion

Emotional support plays a significant role in the mental health of health care workers. While formal mental health support is important, the emotional support network of family, friends and colleagues is also valuable for health care workers to rely on. These connections, especially the support of household members, play an integral role in the holistic well-being of health care workers.

Varying levels of confidence in the adequacy of infection control procedures and perception of clear communication as it relates to control strategies appears to be inversely related to levels of stress and uncertainty. In addition to information on organization-wide measures, providing insights on healthy personal coping behaviours may support worker wellness and retention, ensuring a sustainable, healthy and robust workforce.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Toronto COVID-19 Action Initiative – University of Toronto. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions and statement

RS, LH, AM, MD, PG, ND, GL, WL and WG were involved in conceptualization of the work.

RS, LH, AM, GL and WG were involved in the funding acquisition.

RS, LH, AM, MD, JS, PG, ND, GL, PW, JN and WG conducted the investigation.

RS, LH, AM, MD, JS, PG, ND, GL, PW, WL, JN and WG curated the data.

RS, TF and VR conducted formal analysis.

RS, LH, WG and EL wrote the original draft.

All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Kock JH, Latham HA, Leslie SJ, et al, et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health. 2021;21((1)):104. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10070-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. 2020;3((3)):e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaukat N, Ali DM, Razzak J, et al. Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a scoping review. Int J Emerg Med. 2020;13((1)):40. doi: 10.1186/s12245-020-00299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisely S, Warren N, McMahon L, Dalais C, Henry I, Siskind D, et al. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020:m1642. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew QH, Wei KC, Vasoo S, Sim K, et al. Psychological and coping responses of health care workers toward emerging infectious disease outbreaks. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81((6)):20r13450. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20r13450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styra R, Hawryluck L, Robinson S, Kasapinovic S, Fones C, Gold WL, et al. Impact on health care workers employed in high-risk areas during the Toronto SARS outbreak. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64((2)):177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabarkapa S, Nadjidai SE, Murgier J, Ng CH, et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 and other viral epidemics on frontline healthcare workers and ways to address it: a rapid systematic review. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, Morgan CA, Charney D, Southwick S, et al. Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007;4((5)):35–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KS, Hemmer CR, Taylor JM, Malcom AR, et al. Nursing professionals’ stress level during coronavirus disease 2019: a looming workforce issue. J Nurse Pract. 2021;17((6)):a looming workforce issue–40. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2021.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, et al. Social support: a review. Oxford University Press. 2011:192–217. [Google Scholar]

- Fang XH, Wu L, Lu LS, et al, et al. Mental health problems and social supports in the COVID-19 healthcare workers: a Chinese explanatory study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21((1)):34–217. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02998-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruisoto P, rez MR, a PA, Paladines-Costa B, Vaca SL, rez VJ, et al. Social support mediates the effect of burnout on health in health care professionals. Front Psychol. 2021:623587–217. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.623587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3((3)):e203976–217. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- et al, et al. Occupational burnout syndrome and post-traumatic stress among healthcare professionals during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020;34((3)):553–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styra R, Hawryluck L, Geer A, et al, et al. Surviving SARS and living through COVID-19: healthcare worker mental health outcomes and insights for coping. PLoS One. 2021;16((11)):healthcare worker mental health outcomes and insights for coping–60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, we B, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166((10)):1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss DS, Marmar C, Wilson JP, Keane TM, et al. The impact of event scale—revised. Guilford Press. 1997:399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16((9)):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Xu Q, et al. Family support as a protective factor for attitudes toward social distancing and in preserving positive mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Health Psychol. 2020;27((4)):858–67. doi: 10.1177/1359105320971697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmassi C, Foghi C, Dell’Oste V, et al, et al. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: what can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020:113312–67. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrague LJ, Santos JA, et al. COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: Predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J Nurs Manag. 2020:1653–61. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirci A, Oruc M, Kabukcuoglu K, et al. ‘It was difficult, but our struggle to touch lives gave us strength’: the experience of nurses working on COVID-19 wards. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30((5-6)):732–41. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco P, Bucholz KK, Harrington D, et al. Gender differences in stressful life events, social support, perceived stress, and alcohol use among older adults: results from a National Survey. Subst Use Misuse. 2014;49((4)):456–65. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.846379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moak ZB, Agrawal A, et al. The association between perceived interpersonal social support and physical and mental health: results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Public Health (Oxf) 2010;32((2)):191–201. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach SB, Bamberger P, Biron M, et al. Alcohol consumption and workplace absenteeism: the moderating effect of social support. J Appl Psychol. 2010:334–48. doi: 10.1037/a0018018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C, McNelis M, Swiatkowski P, et al. Social support indirectly predicts problem drinking through reduced psychological distress. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51((5)):608–15. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1126746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara M, Mashizume Y, Takahashi K, et al. Coping mechanisms: exploring strategies utilized by Japanese healthcare workers to reduce stress and improve mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18((1)):1–12. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18010131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson RC, n RA, Hoerster KD, et al, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, occupational functioning, and professional retention among health care workers and first responders. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37((2)):397–408. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07252-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AL-Abrrow H, Al-Maatoq M, Alharbi RK, et al, et al. Understanding employees’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: the attractiveness of healthcare jobs. Glob Bus Organ Excell. 2021;40((2)):19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Norful AA, Rosenfeld A, Schroeder K, Travers JL, Aliyu S, et al. Primary drivers and psychological manifestations of stress in frontline healthcare workforce during the initial COVID-19 outbreak in the United States. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021:20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Guan R, Sun L, et al. Perceived organizational support and PTSD symptoms of frontline healthcare workers in the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan: the mediating effects of self-efficacy and coping strategies. Perceived organizational support and PTSD symptoms of frontline healthcare workers in the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan: the mediating effects of self-efficacy and coping strategies. Appl Psychol Heal Well-Being. 2021:745–60. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e D, Hoxhaj I, Orfino A, Viteritti AM, Janiri L, Pietro ML, et al. Interventions to address mental health issues in healthcare workers during infectious disease outbreaks: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2021:319–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalluto LB, Planz VB, Stokes LA, et al, et al. Transparency and trust during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020:909–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouche S, et al. COVID-19 and employees’ mental health: stressors, moderators and agenda for organizational actions. Emerald Open Res. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- White SJ, Barello S, Marco E, et al, et al. Critical observations on and suggested ways forward for healthcare communication during COVID-19: pEACH position paper. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104((2)):pEACH position paper–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondilis E, Papamichail D, Gallo V, Benos A, et al. COVID-19 data gaps and lack of transparency undermine pandemic response. J Public Health (Oxf) 2021;43((2)):e307–8. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]