Abstract

Objective

A non-negligible proportion of sub-Saharan African (SSA) households experience catastrophic costs accessing healthcare. This study aimed to systematically review the existing evidence to identify factors associated with catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) incidence in the region.

Methods

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, CNKI, Africa Journal Online, SciELO, PsycINFO, and Web of Science, and supplemented these with search of grey literature, pre-publication server deposits, Google Scholar®, and citation tracking of included studies. We assessed methodological quality of included studies using the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies for quantitative studies and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for qualitative studies; and synthesized study findings according to the guidelines of the Economic and Social Research Council.

Results

We identified 82 quantitative, 3 qualitative, and 4 mixed-methods studies involving 3,112,322 individuals in 650,297 households in 29 SSA countries. Overall, we identified 29 population-level and 38 disease-specific factors associated with CHE incidence in the region. Significant population-level CHE-associated factors were rural residence, poor socioeconomic status, absent health insurance, large household size, unemployed household head, advanced age (elderly), hospitalization, chronic illness, utilization of specialist healthcare, and utilization of private healthcare providers. Significant distinct disease-specific factors were disability in a household member for NCDs; severe malaria, blood transfusion, neonatal intensive care, and distant facilities for maternal and child health services; emergency surgery for surgery/trauma patients; and low CD4-count, HIV and TB co-infection, and extra-pulmonary TB for HIV/TB patients.

Conclusions

Multiple household and health system level factors need to be addressed to improve financial risk protection and healthcare access and utilization in SSA.

Protocol registration

PROSPERO CRD42021274830

Introduction

Over 930 million people globally suffered undue financial hardship while obtaining healthcare and about 100 million people were forced into poverty yearly from out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenses in 2019 [1]. As the predominant healthcare financing system in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), OOP payments have hindered the region’s drive towards universal health coverage (UHC) [2]. Besides, OOP healthcare financing is inefficient and highly inequitable, further impoverishing the poorest households in the region [2, 3].

Catastrophic health expenditure (CHE)–defined as OOP payment above an estimated threshold share of total household expenditure at which the household is forced to sacrifice other basic needs, sell assets, incur debts, or be impoverished [4]–engenders a vicious cycle of poverty for some households that choose to seek services and leads to more illnesses for those who cannot afford OOP costs [5]. Improving financial protection to minimize the extent to which households incur CHE and are pushed into poverty due to high medical spending has received substantial attention [1, 4, 6]. To this end, the United Nations in 2015 included CHE incidence as a key indicator to track progress towards UHC (SDG 3.8.2) [1, 4, 6]. Reducing CHE incidence is one of the key objectives of the global, regional, and national health policy drive towards UHC and human development [1, 5].

Our previous study had demonstrated that a non-negligible proportion of households annually experience CHE in SSA (16.5% at the 10% total household expenditure threshold and 8.8% at the non-food expenditure threshold) [7]. There is, however, a wide demand for a better understanding of the factors associated with catastrophic OOP expenditure in the region to fine-tune interventions to adequately protect households [5]. Hence, this study aims to systematically review the literature to identify the patients, household, and health system level factors associated with CHE incidence in SSA countries. For a comprehensive review, we sought both quantitative and qualitative studies, as qualitative studies may identify key themes not found, described, or discussed in quantitative studies [8, 9]. Our findings could help identify at-risk populations for community-wide and/or vertical disease-specific interventions.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was registered on PROSPERO: CRD42021274830; and the findings reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [10].

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, CNKI, AJOL, African Index Medicus, PsycINFO, SciELO, Scopus, and Web of Science for studies published from 01 January 2000 to 31 December 2021 conducted in any of the 48 World Bank-defined SSA countries. Two authors (PE and LOL) independently searched the literature in February 2022 using search terms covering catastrophic health expenditure, financial catastrophe, risk factors, “factors associated with”, and sub-Sahara Africa–S1 Table. Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were used to broaden the search. We also searched grey literature websites: New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature and Open Grey; pre-publication server deposits: medRxIV and PrePubMed; Google Scholar®; and tracked references of included studies for relevant articles. We considered studies published in any of the six African Union languages: Arabic, English, French, Kiswahili, Portuguese, and Spanish; and translated non-English publications using a translation service. We underwent a moderation exercise to ensure uniformity; screened abstracts according to prior eligibility criteria (S2 Table); retrieved full texts for eligible studies; and resolved discrepancies by discussion. We used Mendeley Desktop® to identify and remove duplicates.

Data extraction

At least two authors (PE, LOL, LUA, CAO, and UJA) independently extracted data from included studies using a template. We extracted the following data from each included study: authors names, publication status, study setting, publication year, study design, data source and authors’ description of the data representativeness, study period, sampling method, sample size (in households), and factors associated with CHE. We extracted reported adjusted odds ratio with the confidence interval at 5.0% statistical significance for each CHE-associated factor. Where two or more studies used the same secondary data to identify CHE-associated factors, we first assessed both studies for unique factors, but if similar factors were evaluated, we then considered the peer-review status of the studies; prioritizing peer-reviewed studies over non-peer-reviewed studies. Where a study described CHE-associated factor using more than one CHE definition, we extracted data for both definitions {10% total household expenditure (THE) and 40% non-food expenditure (NFE)}. For qualitative studies; we manually extracted all text under the headings ‘results/conclusions’. We cross-checked all extracted data for discrepancies which were resolved through discussion.

Risk of bias assessment

At least two authors (PE, CAO, LUA, UJA, and LOL) independently assessed the quality of included quantitative studies using the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS tool) [11], and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative studies [12]. We resolved discrepancies in quality assessment scores by discussion until 100% agreement. We categorized the articles’ quality into high (studies met ≥ 70% of the quality criteria), moderate (between 40% and 69% of the quality criteria), and low (< 40% of the quality criteria). We used Microsoft Excel® to organize extracted data.

Data analysis

We first summarized the included studies descriptively. To synthesize the evidence, we performed meta-analysis and narrative synthesis following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Methods Programme [9, 13] guidelines. We pooled studies reporting quantitative estimates (odds ratios) from regression or matching analysis for CHE-associated factors in a random-effects meta-analysis to obtain pooled effect estimates. Random effects meta-analysis allows for differences in the treatment effect from study to study because of real differences in the treatment effect in each study as well as sampling variability [14]. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 16.1 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX). Where meta-analysis was not possible due to difference in the definition of CHE-associated factors, we analyzed the reported quantitative estimates narratively.

For qualitative data, we independently performed line-by-line coding of text to group similar concepts and developed new codes when necessary. We organized free codes into descriptive major themes and sub-themes using an inductive approach as detailed by Thomas and Harden [15]. Each reviewer first did this independently and then as a group. Through discussion more abstract or analytical themes emerged and we resolved discrepancies between reviewers through discussion and consensus was achieved on all occasions. Finally, we globally assessed findings from both quantitative studies including meta-analysis for each CHE-associated factor–based of breadth of evaluation in included studies, consistency of an effect on CHE incidence, and methodological quality of included studies evaluating this factor–and when available, triangulated these with the participants’ lived experiences reported in qualitative studies to categorize each CHE-associated factor as either significant or marginal. We categorized a factor as “significant” if it was widely evaluated factors that consistently diminished or exaggerated the likelihood of CHE incidence. Otherwise, we categorized such factor as “marginal”.

Deviations from study protocol

The original protocol was for a quantitative study. We decided to include qualitative studies to enrich our understanding of the key drivers of CHE based on individuals’ lived experiences, which population-based quantitative studies do not cover.

Results

Study characteristics

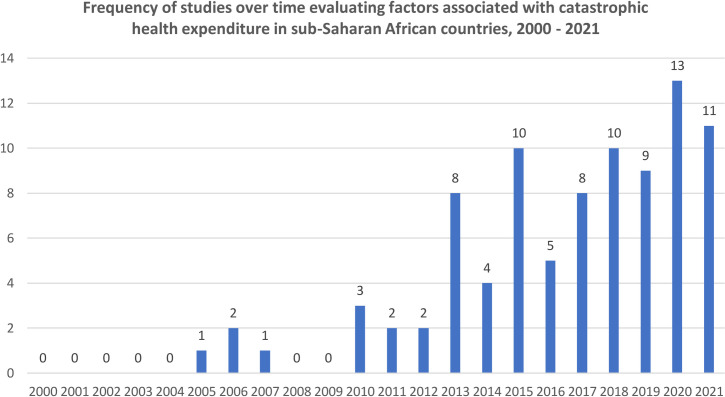

We identified 965 unique articles published between 2000 and 2021 (Fig 1). Of these articles, 122 full-text articles were screened for eligibility and 89 studies met inclusion criteria for this review [16–104] (Table 1). Included studies were 80 peer-reviewed publications, four working papers, and five dissertations, and covered 3,112,322 individuals in 650,297 households in 29 SSA countries. Included articles were published between 2005 to 2021 (Fig 2); were predominantly English-language articles (n = 85; 95.5%); mostly used nationally-representative samples (n = 48; 53.9%); and mostly estimated CHE incidence using ‘non-food expenditure’ definition (n = 53; 59.6%)–Table 2.

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; CHE: Catastrophic health expenditures.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

| Study, Publication status |

Study location (Country) | Study design | Data source, Study period (year) |

Sample size (households) | CHE definition | Study health area | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeniji & Lawanson 2018 [16] Published |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Harmonized Nigeria Living Standard Survey (HNLSS), 2009/2010 | 38,700 | 40% NFE | General health care | Moderate |

| Adisa 2015 [17] Published |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Nigeria General Household & Population Survey (NGHPS), 2010 | 1,176 | 10% THE | General health care | High |

| Aidam et al. 2016 [18] Published |

Ghana | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from household survey in Ga South Municipality, Ghana, 2013 | 117 | 40% NFE | General health care | Moderate |

| Akazili 2010 [19] PhD thesis |

Ghana | Cross-sectional study | Ghana Living Standard Survey (GLSS), 2005 | 8,687 | 10% THE 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Akinkugbe et al. 2012 [20] Published |

Botswana Lesotho |

Cross-sectional study | Botswana Household and Expenditure Survey (HIES), 2002/2003 and Lesotho Household budget Survey, 2002/2003 | 6,053 (BWA) 6,882 (LSO) |

40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Aregbesola & Khan 2018 [21] Published |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Nigeria Harmonised Living Standard Survey (HNLSS), 2009/2010 | 38,700 a | 10% THE 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Arsenault et al. 2013 [22] Published |

Mali | Case-control study | Primary data from case–control study in Kayes region, Mali, 2008–2011 | 484 | 10% THE | Reproductive health (RH) services | High |

| Aryeetey et al. 2016 [23] Published |

Ghana | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from household survey in Eastern and Central regions of Ghana, 2009 | 3,300 | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Assebe et al. 2020 [24] Published |

Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | Ethiopia Health Account (EHA); and health facility-based survey, 2016/2017 | 1,006 (HIV) 787 (TB) | 10% THE | HIV/AIDS & Tuberculosis | High |

| Atake & Amendah 2018 [25] Published |

Togo | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from household survey in Lomé, Togo, 2016 | 1,180 | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Attia-Konan et al. 2020 [26] Published |

Cote d’Ivoire | Cross-sectional study | Cote d’Ivoire National household living standards survey, 2015 | 12,899 | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Babikir et al. 2018 [27] Published |

South Africa | Panel survey | National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS), 2013 | 10,236 | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Barasa et al. 2017 [28] Published |

Kenya | Cross-sectional study | Kenya Household Expenditure and Utilization Survey, 2013 | 33,675 | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Beauliere et al. 2010 [29] Published |

Cote d’Ivoire | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional survey of 18 hospitals in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, 2007 | 1,190 | 40% NFE | HIV/AIDS | High |

| Borde et al. 2020 [30] Published |

Ethiopia | Cohort study | Primary data from cohort study in 3 kebeles in Wonago district, southern Ethiopia, 2017 | 794 | 10% THE 40% NFE | Reproductive health (RH) service | High |

| Botman et al. 2021 [31] Published |

Tanzania | Mixed method (Survey & Observation) | Cross-sectional survey and observation of patients in a regional referral hospital in the Manyara, Tanzania, 2017 | 67 | 10% THE | Trauma (Burns patients) | High |

| Bousmah et al. 2021 [32] Published |

Cameroun | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from two cross-sectional surveys in the HIV ART clinics in six regions in Cameroun, 2006/2007 and 2014 | 5,281 | 40% NFE | HIV/AIDS | High |

| Boyer et al. 2011 [33] Published |

Cameroun | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional surveys in 27 hospitals in Cameroun, 2006–2007 | 3,151 a | 10% THE | HIV/AIDS | High |

| Brinda et al. 2014 [34] Published |

Tanzania | Cross-sectional study | Tanzania National Panel Survey (TZNPS), 2008/2009 | 3,265 | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Buiguit et al. 2015 [35] Published |

Kenya | Cross-sectional study | Indicator Development for Surveillance of Urban Emergencies Project, 2011 | 8,171 | 10% THE | General health care | High |

| Chabrol et al. 2019 [36] Published |

Cameroun | Qualitative | Interviews with affected patients in reference hospitals in Yaoundé, Cameroon, 2014 | 12 | 10% THE | HBV and HCV | High |

| Chukwu et al. 2017 [37] Published |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from multi-hospital survey in four states in Nigeria, 2015 | 92 | 10% THE | Buruli ulcer (NTD) | High |

| Cleary et al. 2013 [38] Published |

South Africa | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from household survey in four provinces (Western Cape, Guateng, Mpumalanga, & KwaZulu Nata) in South Africa, 2011 | 1,267 (HIV) 1,231 (RHS) 1,229 (TB) |

10% THE | HIV/AIDS, RH services, & Tuberculosis | High |

| Counts & Skordis-Worrall 2016 [39] Published | Tanzania | Panel survey | Kagera Health and Development Surveys, 1991–2010 | 900 | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Dhufera et al. 2022 [40] Published |

Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from trauma units of multiple hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019 | 452 | 40% NFE | Trauma | High |

| Doamba et al. 2013 [41] Published {FRENCH} |

Burkina Faso | Cross-sectional study | Burkina Faso Enquête Intégrale sur les Conditions de Vie des Ménages (EICVM), 2009 | 8,404 | 40% NFE | General health care | Moderate |

| Dyer et al. 2013 [42] Published |

South Africa | Prospective cohort study | Primary data from cross-sectional hospital survey, Cape Town, South Africa 2009 to 2011 | 148 | 40% NFE | Reproductive Health (RH) services | High |

| Ebaidalla & Ali 2019 [43] Published |

Sudan | Cross-sectional study | Sudan National Baseline Households Survey (NBHS), 2009. | 7,913 a | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Ebaidalla 2021 [44] Published |

Sudan | Cross-sectional study | Sudan National Baseline Household Survey (NBHS), 2009 and 2014 | 7,913 (2009) 11,953 (2014) |

10% THE | General health care | Moderate |

| Edoka et al. 2017 [45] Published |

Sierra Leone | Cross-sectional study | Sierra Leone integrated household survey (SLIHS), 2003 and 2011 | 6,800 (2003) 3,700 (2011) |

10% THE | General health care | High |

| Ekman 2007 [46] Published |

Zambia | Cross-sectional study | Zambian Living Conditions Monitoring Survey II (LCMS II), 1998 | 16,000 | 10% THE | General health care | High |

| Fink et al. 2013 [47] Published |

Burkina Faso | Pre-intervention baseline survey | Nouna Health and Demographic Surveillance System Survey, 2003 | 983 | 10% THE | General health care | High |

| Hailemichael et al. 2019 [49] Published |

Ethiopia | Case-control study | Primary data from population-based, cross-sectional study in Sodo district of the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Regional State, Ethiopia, 2015 | 257 | 10% THE | Chronic NCDs | High |

| Hailemichael et al. 2019 [48] Published |

Ethiopia | Case-control study | Primary data from a population-based cross-sectional household survey in Sodo district in southern Ethiopia, 2015 | 579 | 40% NFE | Chronic NCDs | High |

| Hilaire 2018 [50] Working Paper |

Benin | Cross-sectional survey | Benin Integrated Modular Survey on Living Condition of Households, 2009 | 15,411 | 10% THE | General health care | High |

| Ibukun & Adebayo 2021 [51] Published |

Nigeria | Mixed method (Survey & Interviews) | Cross-sectional survey and interviews of hospital patients in Nigeria, 2019 | 1,320 | 40% NFE | Chronic NCDs | High |

| Ibukun & Komolafe 2018 [52] Published |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional survey | Nigeria General Household Survey Panel (GHS), 2015/2016 | 4,581 | 40% NFE | General health care | Moderate |

| Ilesanmi et al. 2014 [53] Published |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional survey | Primary data from household survey in Oyo State, SW Nigeria, 2012 | 714 | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Ilunga-Ilunga et al. 2015 [54] Published |

Congo, DR | Cross-sectional survey | Primary data from multi-hospital survey in Kinshasa, Congo DR, 2012 | 1,350 | 10% THE 40% NFE |

Malaria | High |

| Janssen et al. 2016 [55] Published |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from household survey in rural Kwara State, Nigeria, 2009 | 1,450 | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Kaonga et al. 2019 [56] Published |

Zambia | Cross-sectional study | Zambian Household Health Expenditure and Utilisation Survey, 2014 | 12,000 | 10% THE | General health care | High |

| Kasahun et al. 2020 [57] Published |

Ethiopia | Cross-sectional survey | Primary data from cross-sectional from multiple hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018 | 352 | 10% THE | Chronic NCDs | High |

| Khatry et al. 2013 [58] Published {FRENCH} |

Mauritania | Cross-sectional study | Mauritania Enquête Permanente sur les Conditions de Vie des ménages (EPCV), 2008 | 13,705 | 40% NFE | General health care | Moderate |

| Kihaule 2015 [59] Published |

Tanzania | Cross-sectional survey | Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey, 2009 | 10,300 | 40% NFE | General health care | Moderate |

| Kimani et al. 2016 [60] Published |

Kenya | Cross-sectional study | Kenya Household Expenditure Utilization Survey (KHHEUS), 2007 | 8,844 | 10% THE 40% NFE | General health care | Low |

| Kirubi et al. 2021 [61] Published |

Kenya | Cross-sectional survey | Kenya National Tuberculosis Programme Patient Cost Survey, 2017 | 1,071 | 10% THE | Tuberculosis | High |

| Kusi et al. 2015 [62] Published |

Ghana | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional household survey in Kwaebibirem, Asutifi, and Savelugu-Nanton districts, Ghana, 2011 | 2,430 | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Kwesiga et al. 2020 [63] Published |

Uganda | Cross-sectional study | Uganda National Household Survey (NHS), 2005/2006, 2009/2010, 2012/2013, 2016/2017 | 7,400 (2005) 6,887 (2009) 7,500 (2012) 17,320 (2016) |

10% THE | General health care | High |

| Lamiraud et al 2005 [64] Working Paper |

South Africa | Cross-sectional study | World Health Survey, 2002 | 2,602 | 40% NFE | General health care | Moderate |

| Lu et al. 2012 [65] Published |

Rwanda | Cross-sectional study | Rwanda Integrated Living Conditions Survey, 2000 | 6,408 | 40% NFE | General health care | Moderate |

| Lu et al. 2017 [66] Published |

Rwanda | Cross-sectional study | Rwanda Integrated Living Conditions Survey, 2005 & 2010 | 6,900 (2005) 14,308 (2010) |

40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Masiye et al. 2016 [67] Published |

Zambia | Cross-sectional study | Zambia Household Health Expenditure & Utilization Survey (ZHHEUS), 2014 | 11,847 | 10% THE | General health care | High |

| Mulaga et al. 2021 [68] Published |

Malawi | Cross-sectional study | Malawi Integrated Household Survey (IHS4), 2016/2017 |

12,447 | 10% THE 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Muttamba et al. 2020 [69] Published |

Uganda | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional survey in 67 TB diagnostic and treatment units in Uganda, 2017 | 1,178 | 10% THE | Tuberculosis | High |

| Mutyambizi et al. 2019 [70] Published |

South Africa | Cross-sectional | Primary data from cross-sectional survey at two public hospitals in Tshwane, Gauteng State, South Africa, 2017 | 395 | 40% NFE | Chronic NCDs | High |

| Mwai & Muriithi 2016 [71] Published |

Kenya | Cross-sectional study | Kenya Household Health Expenditure & Utilization Survey (KHHEUS), 2007 |

8,453 a | 40% NFE | General health care | Low |

| Negin et al. 2016 [72] Published |

South Africa | Cross-sectional study | Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE) South Africa Wave 1, 2007/2008. | 2,969 | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Ngcamphalala 2015 [73] MPH thesis |

Eswatini (Swaziland) | Cross-sectional study | Swaziland Household Income and Expenditure Survey (SHIES), 2009/2010 | 3,167 | 10% THE | General health care | Moderate |

| Nguyen et al. 2011 [74] Published |

Ghana | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from household survey in Nkoranza and Offinso districts, Ghana, 2007 | 2,500 | 10% THE | General health care | High |

| Njagi et al. 2020 [75] Published |

Kenya | Cross-sectional study | Kenya Household Health Expenditure & Utilisation Survey, 2007 and 2013 | 3,728 (2007) 16,526 (2013) |

40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Njuguna et al. 2017 [76] Published |

Kenya | Cross-sectional study | Kenya Household Health Utilization & Expenditure Survey (KHHUES), 2013 | 33,675 a | 40% NFE | General health care | Low |

| Ntambue et al. 2019 [77] Published |

Congo, DR | Mixed method (Survey & Interviews) | Cross-sectional survey and interviews of hospital patients in Nigeria, 2015 | 1,627 | 40% NFE | Reproductive Health (RH) services | High |

| Nundoochan et al. 2019 [78] Published |

Mauritius | Cross-sectional study | Mauritius Household Budget Surveys, 2001/2002, 2006/2007, and 2012 | 6,720 (2001) 6,720 (2006) 6,720 (2012) |

10% THE 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Nwanna-Nzewunwa et al. 2021 [79] Published |

Uganda | Mixed method (Prospective cohort and Qualitative) | Survey and interviews of affected patients at Soroti Regional Referral Hospital Uganda, 2018/2019 | 546 | 10% THE | Surgery | High |

| Nyankangi et al. 2020 [80] MSc Thesis |

Kenya | Cross-sectional study | Kenya Household Health Utilization & Expenditure Survey (KHHUES), 2018 | 37,500 | 40% NFE | Chronic NCD | High |

| Obembe & Fonn 2020 [81] Published |

Nigeria | Qualitative study | Interviews with patients and family members liable for paying for surgery in Ibadan, Nigeria, 2017 | 31 | 10% THE | Emergency surgery | High |

| Obembe et al. 2021 [82] Published |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional household survey in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria, 2017 | 450 | 10% THE | Emergency surgery | High |

| Ogaji & Adesina 2018 [83] Published |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional household survey in Yenagoa, Bayelsa St, Nigeria, 2012 | 525 | 10% THE | General health care | Moderate |

| Okoroh et al. 2020 [84] Published |

Ghana | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional survey at a regional referral hospital, Accra, Ghana, 2017 | 196 | 40% NFE | Surgery | High |

| Olatunya et al. 2015 [85] Published |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional survey at a regional referral hospital Ado Ekiti, Ekiti State, 2014 | 111 | 10% THE | Chronic NCD | High |

| Onah & Govender 2014 [86] Published |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional survey in Nsukka LGA, Nigeria, 2012 | 411 | 10% THE | General | High |

| Onarheim et al. 2018 [87] Published |

Ethiopia | Qualitative study | Interviews and focus group discussions with caretakers Ethiopia, 2015 | 41 interviews and 7 FGDs | 10% THE | Newborn | High |

| Owusu-Sekyere 2015 [88] MPhil thesis |

Ghana | Cross-sectional study | Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS 6), 2012 | 16,772 | 40% NFE | General | Moderate |

| Petitfour et al. 2021 [89] Published |

Burkina Faso | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional survey at the sole referral hospital in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2015 | 1,323 | 10% THE | Trauma | High |

| Rickard et al. 2017 [90] Published |

Rwanda | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional survey at a regional referral hospital, Kigali Rwanda, 2014/2015 | 245 | 40% NFE | Surgery | High |

| Saksena et al. 2010 [91] Working paper |

Burkina Faso Chad Congo, Rep Cote d’Ivoire Ethiopia Ghana Kenya Malawi Mali Mauritania Mauritius Namibia Swaziland Zambia Zimbabwe |

Cross-sectional study | WHO World Health Survey, 2002–2003 | 4,948 (BFA) 4,875 (TCD) 3,070 (COG) 3,245 (CIV) 5,090 (ETH) 4,165 (GHA) 4,640 (KEN) 5,551 (MWI) 5,209 (MLI) 3,907 (MRT) 3,958 (MUS) 4,379 (NAM) 3,121 (SWZ) 6,165 (ZMB) 4,264 (ZWE) |

40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Salari et al. 2019 [92] Published |

Kenya | Cross-sectional study | Kenya Household Health Utilization & Expenditure Survey (KHHUES), 2018 | 37,500 a | 10% THE 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Sanoussi & Ameteglo 2019 [93] {FRENCH} Working paper |

Togo | Cross-sectional study | Togo Questionnaire of Basic Indicators of Well-being (QUIBB) survey, 2015 | 2,400 | 10% THE 40% NFE | General health care | Moderate |

| Sene & Cisse 2015 [94] Published | Senegal | Cross-sectional study | Senegal Poverty Monitoring Survey, 2011 | 5,953 | 10% THE | General health care | Moderate |

| Shikuro et al. 2020 [95] Published |

Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional household survey, 2017 | 479 | 40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Shumet et al. 2021 [96] Published |

Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional study in Mandura, Ethiopia, 2018 | 302 | 10% THE | Chronic NCDs | High |

| Sichone 2020 [97] Graduate MSc thesis |

Zambia | Cross-sectional study | Zambia Household Health Expenditure & Utilisation Survey, 2014 | 2,164 | 10% THE | Malaria in children < 5 year of age | High |

| Sow et al. 2013 [98] {FRENCH} Published |

Senegal | Cross-sectional study | Senegal Enquêtes de Suivi de la Pauvreté au Sénégal, 2011 | 18,000 | 40% NFE | General health care | Moderate |

| Su et al. 2006 [99] Published |

Burkina Faso | Cross-sectional study | Nouna Health District Household Survey (NHDHS), 2000/2001 | 774 | 40% NFE | General health care | Moderate |

| Tolla et al. 2017 [100] Published |

Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional survey of CVD patients in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2015 | 589 | 10% THE | Chronic NCD | High |

| Tsega et al. 2021 [101] Published |

Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from cross-sectional survey of CVD patients in Bahir Dar city, Ethiopia, 2019 | 422 | 40% NFE | Chronic NCD | High |

| Ukwaja et al. 2013 [102] Published |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Primary data from population-based household survey, 2011 | 452 | 40% NFE | Tuberculosis | High |

| Xu et al. 2006 [103] Published |

Uganda | Cross-sectional study | Uganda Socio-economic Surveys (USS), 2000 and 2003 | 10,691 (2000) 9,710 (2003) |

40% NFE | General health care | High |

| Zeng et al. 2018 [104] Published |

Zimbabwe | Cross-sectional study | Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency Household Survey, 2016 | 7,135 | 10% THE | General health care | High |

a Samples were not included in the overall study participants total reported

NCD: Non-communicable disease, NTD: Neglected tropic disease, RH: Reproductive health, TB: Tuberculosis

BFA: Burkina Faso, TCD: Chad, COG: Congo, Republic, CIV: Cote d’Ivoire, ETH: Ethiopia, GHA: Ghana, KEN: Kenya, MWI: Malawi, MLI: Mali, MRT: Mauritania, MUS: Mauritius, NAM: Namibia, SWZ: Eswatini (Swaziland), ZMB: Zambia, and ZWE: Zimbabwe

Fig 2. Frequency of included studies over time in sub-Saharan Africa, 2000–2021.

Table 2. Summary characteristics of included studies.

| Study characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| N = 89 | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa region | |

| ◦ Central SSA | 6 (6.7%) |

| ◦ East SSA | 37 (41.6%) |

| ◦ South SSA | 20 (22.5%) |

| ◦ West SSA | 41 (46.1%) |

| Top-five study countries | |

| ◦ Nigeria | 14 (15.7%) |

| ◦ Ethiopia | 12 (13.5%) |

| ◦ Kenya | 10 (11.2%) |

| ◦ Ghana | 8 (9.0%) |

| ◦ South Africa | 6 (6.7%) |

| Study population | |

| ◦ General (Entire community) | 52 (58.4%) |

| ◦ Patients with NCDs | 10 (11.2%) |

| ◦ Pregnant and nursing mothers and newborns | 6 (6.7%) |

| ◦ Infectious diseases (HIV, TB, HBV, and HCV) | 10 (11.2%) |

| ◦ Surgery and trauma | 8 (9.0%) |

| ◦ Malaria and neglected tropical diseases | 4 (4.5%) |

| Study language | |

| ◦ English | 85 (95.5%) |

| ◦ French | 4 (4.5%) |

| Definition of catastrophic health expenditure used | |

| ◦ 10% total household expenditure | 36 (40.5%) |

| ◦ 40% non-food expenditure | 43 (48.3%) |

| ◦ Both definitions | 10 (11.2%) |

| Study design | |

| ◦ Quantitative | 82 (92.1%) |

| ◦ Qualitative | 3 (3.4%) |

| ◦ Mixed methods | 4 (4.5%) |

| Data source | |

| ◦ Primary data | 41 (46.1%) |

| ◦ Secondary source | 48 (53.9%) |

| Publication status | |

| ◦ Peer-reviewed | 80 (89.9%) |

| ◦ Non-peer-reviewed | 9 (10.1%) |

| Study quality | |

| ◦ High quality | 70 (78.6%) |

| ◦ Moderate quality | 16 (18.0%) |

| ◦ Low quality | 3 (3.4%) |

Of the 89 included studies, 70 (78.6%) were rated as high quality, 16 (18.0%) as moderate quality, and the remaining 3 (3.6%) as low quality–Table 1. Of note, all included quantitative studies used sample frames that closely represented the target population (AXIS tool Item 5) and used selection procedures that likely selected samples representative of the underlying population (AXIS tool Item 6). Also, included qualitative studies used sampling techniques that ensured the identification and selection of individuals that recently suffered catastrophic health expenses.

Catastrophic health expenditure-associated factors

Included studies involved 82 population-based studies reporting quantitative estimates, of which a total of 73 were included in the 71 different random-effects meta-analysis. Nine studies were included in narrative synthesis. Quantitative data from four mixed methods studies were also included in the narrative synthesis. Results from quantitative meta-analysis were reported in two broad categories: population-level factors and disease-specific factors (Tables 3 and 4). Seven studies reporting qualitative data (3 qualitative studies and 4 mixed-methods) met the inclusion criteria, all of which were included in thematic analysis (Table 5). Qualitative data revealed two main themes associated with households’ CHE incidence: low socioeconomic status and being uninsured (Table 6). We presented excerpts of supportive qualitative findings with the relevant quantitative findings and a thematic analysis map in S1 Fig.

Table 3. Socio-demographic factors associated with population-level catastrophic health expenditure in SSA countries.

| 10% Total Household Expenditure | 40% Non-Food Expenditure | Authors’ global assessment of factor’s weight | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Sample size | Pooled OR (95% CI) | No. of studies | Sample size | Pooled OR (95% CI) | ||

| Household characteristics | |||||||

| ◦ Residence (ref = urban) | 14 | 227,692 | 1.01 (0.93–1.09) | 15 | 299,595 | 1.11 (0.93–1.36) | Significant |

| ◦ Socioeconomic status (ref = wealthiest) | 15 | 216,086 | 1.99 (1.32–2.98) | 20 | 284,017 | 3.02 (2.23–4.08) | Significant |

| ◦ Household size | 10 | 160,933 | 1.07 (1.02–1.13) | 18 | 258,456 | 1.06 (0.99–1.12) | Significant |

| ◦ Insurance status (ref = insured) | 9 | 123,203 | 1.69 (0.69–4.16) | 14 | 242,511 | 1.16 (0.65–2.08) | Significant |

| ◦ Social safety net (benefits, vouchers, etc.) | 1 | 8,171 | 0.63 (0.52–0.79) | 1 | 10,236 | 1.29 (1.14–1.44) | Marginal |

| ◦ Marginalization status | 0 | 1 | 33,675 | 1.38 (1.14–1.67) | Marginal | ||

| Household head characteristics | |||||||

| ◦ Sex (ref = Male) | 14 | 219,721 | 1.03 (0.95–1.11) | 17 | 290,879 | 1.04 (0.97–1.11) | Marginal |

| ◦ Age (ref = young adult, < 40 years) | 8 | 109,687 | 1.07 (1.00–1.15) | 11 | 183,036 | 0.96 (0.83–1.11) | Marginal |

| ◦ Marital status: widowed/divorced (ref = married) | 6 | 116,802 | 0.97 (0.93–1.03) | 8 | 169,958 | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | Marginal |

| ◦ Education (ref = at least secondary educ.) | 12 | 199,103 | 1.13 (0.94–1.35) | 16 | 257,656 | 1.13 (0.94–1.35) | Marginal |

| ◦ Employment status (ref = employed) | 13 | 220,874 | 1.19 (0.96–1.48) | 10 | 212,289 | 1.16 (1.05–1.29) | Significant |

| Household members | |||||||

| ◦ Presence of children < 5 years old | 9 | 148,188 | 1.07 (1.00–1.15) | 10 | 147,023 | 0.96 (0.83–1.11) | Marginal |

| ◦ Presence of women of reproductive age | 1 | 525 | 0.19 (0.10–0.36) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Presence of elderly person | 12 | 193,093 | 1.06 (1.03–1.08) | 13 | 239,345 | 1.30 (1.15–1.47) | Significant |

| ◦ Chronic illness in a household member | 9 | 128,419 | 2.12 (1.76–2.55) | 14 | 222,213 | 1.93 (1.62–2.31) | Significant |

| ◦ Hospitalization of a household member | 5 | 27,236 | 2.62 (0.93–7.42) | 6 | 70,852 | 3.91 (2.07–7.35) | Significant |

| ◦ Disability in a household member | 1 | 1,176 | 0.84 (0.47–1.48) | 4 | 36,687 | 1.10 (0.82–1.46) | Marginal |

| ◦ Smoker (ref = non-smoker) | 0 | 1 | 38,700 | 1.11 (1.10–1.12 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Obesity/Overweight | 0 | 1 | 4,842 | 1.02 (0.91–1.34) | Marginal | ||

| Health system factors | |||||||

| ◦ Health facility level (ref = primary care) | 4 | 42,518 | 1.85 (1.18–2.91) | 1 | 1,180 | 3.82 (1.36–19.72) | Significant |

| ◦ Health facility type: private (ref = public) | 9 | 94,514 | 1.18 (0.48–2.90) | 6 | 74,981 | 1.08 (0.36–3.26) | Significant |

| ◦ Health facility type: mission (ref = public) | 4 | 35,785 | 2.17 (0.70–6.69) | 1 | 12,447 | 2.28 (1.24–4.15) | Marginal |

| ◦ Distance to health facility | 5 | 54,694 | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 4 | 32,344 | 1.01 (0.68–1.50) | Marginal |

| ◦ Number of health facilities in county | 0 | 1 | 33,675 | 1.00 (1.00–1.02) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ First sought care from traditional healers | 0 | 2 | 18,533 | 1.64 (0.42–6.44) | Marginal | ||

| Other factors | |||||||

| ◦ Violence against women | 0 | 1 | 8,297 | 1.41 (1.05–1.91) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Owns house (ref = rent/lease house) | 1 | 16,000 | 1.86 (1.17–2.97) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Regular use of mosquito bed nets | 1 | 1,176 | 1.35 (0.83–2.20) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Owns business | 1 | 8,171 | 1.02 (0.86–1.22) | 0 | Marginal | ||

Abbreviations: HF: Health facility

Table 4. Socio-demographic factors associated with disease-specific catastrophic health expenditure in SSA countries.

| 10% Total household expenditure | 40% Non-food expenditure | Authors’ global assessment of factor’s weight | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Sample size | Pooled OR (95% CI) | No. of studies | Sample size | Pooled OR (95% CI) | ||

| Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) | |||||||

| ◦ Residence (ref = urban) | 3 | 1,250 | 1.29 (0.51–3.29) | 4 | 46,924 | 1.00 (0.78–1.28) | Significant |

| ◦ Socioeconomic status (ref = wealthiest) | 5 | 8,803 | 4.72 (1.05–21.24) | 4 | 39,821 | 1.33 (1.06–1.68) | Significant |

| ◦ Household size | 1 | 1,056 | 2.06 (0.75–5.60) | 2 | 10,322 | 1.06 (0.92–1.21) | Marginal |

| ◦ Insurance status (ref = insured) | 0 | 3 | 47,243 | 1.01 (0.93–1.10) | Significant | ||

| ◦ Household head sex (ref = male) | 1 | 257 | 1.11 (0.48–3.33) | 2 | 1,899 | 1.25 (1.10–1.43) | Marginal |

| ◦ Patients’ sex (ref = male) | 2 | 799 | 1.05 (0.44–2.53) | 3 | 46,345 | 1.09 (0.88–1.36) | Marginal |

| ◦ Patients’ marital status: widow/divorced (ref = married) | 2 | 706 | 2.72 (0.88–8.38) | 3 | 46,345 | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) | Marginal |

| ◦ Patients’ education (ref = at least secondary educ.) | 3 | 1,056 | 0.77 (0.35–1.69) | 2 | 38,501 | 1.23 (0.65–2.33) | Marginal |

| ◦ Patients’ employment status (ref = employed) | 3 | 1,388 | 0.99 (0.50–1.96) | 3 | 37,922 | 1.53 (1.01–2.34) | Marginal |

| ◦ Presence of elderly persons in household | 4 | 1,645 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 2 | 38,079 | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | Marginal |

| ◦ Presence of children in household | 1 | 257 | 0.50 (0.20–1.60) | 1 | 1,001 | 0.69 (0.45–1.05) | Marginal |

| ◦ Chronic illness in a household member | 1 | 257 | 2.10 (1.10–4.60) | 3 | 46,502 | 1.26 (1.11–1.43) | Significant |

| ◦ Disability in a household member | 1 | 257 | 2.10 (1.10–4.60) | 1 | 579 | 1.50 (1.00–2.70) | Significant |

| ◦ Health facility type (ref = public) | 2 | 993 | 5.42 (0.36–82.13) | 2 | 1,742 | 1.00 (0.49–2.07) | Marginal |

| ◦ Duration of NCDs diagnosis | 1 | 589 | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| Reproductive, maternal, newborn, & child Health | |||||||

| ◦ Residence (ref = urban) | 1 | 484 | 7.14 (2.51–20.41) | 0 | Significant | ||

| ◦ Socioeconomic status (ref = wealthiest) | 1 | 1,231 | 0.87 (0.71–1.07) | 2 | 1,775 | 33.97 (1.70–67.74) | Significant |

| ◦ Insurance status (ref = insured) | 0 | 1 | 148 | 2.11 (0.92–4.80) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Mothers’ marital status (ref = married) | 0 | 1 | 1,627 | 2.40 (1.50–3.50) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Mothers’ education (ref = at least secondary educ) | 2 | 1,715 | 2.05 (0.49–8.49) | 1 | 148 | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) | Marginal |

| ◦ Household head employment status (ref = employed) | 1 | 1,231 | 1.06 (0.87–1.29) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Distance to Health facility > 5km (ref < 5 km) | 1 | 484 | 1.02 (0.43–2.41) | 0 | Significant | ||

| ◦ Distance to Health facility > 40 km (ref < 5 km) | 1 | 484 | 2.54 (1.22–5.30) | 0 | Significant | ||

| ◦ Blood transfusion | 1 | 484 | 2.78 (1.47–5.25) | 0 | Significant | ||

| ◦ Complicated vaginal delivery (ref = UVD) | 0 | 1 | 1,627 | 1.80 (1.40–2.40) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Caesarean delivery (ref = UVD) | 0 | 1 | 1,627 | 5.00 (3.90–6.30) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Delivery at unplanned facility | 0 | 1 | 1,627 | 1.30 (1.10–1.70) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Referral status (ref = not referred) | 0 | 1 | 1,627 | 2.80 (2.20–3.60) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Neonatal Intensive care unit admission | 1 | 794 | 2.56 (1.02–6.44) | 1 | 1,627 | 2.40 (1.90–3.10) | Significant |

| Surgery and trauma care | |||||||

| ◦ Residence (ref = urban) | 1 | 450 | 1.03 (0.17–5.56) | 1 | 452 | 2.95 (1.80–4.80) | Significant |

| ◦ Socioeconomic status (ref = wealthiest) | 1 | 450 | 31.3 (4.42–221.86) | 1 | 452 | 2.23 (1.13–4.90) | Significant |

| ◦ Insurance status (ref = insured) | 1 | 450 | 5.88 (4.55–333.33) | 2 | 648 | 9.54 (3.23–28.16) | Significant |

| ◦ Sex of household head (ref = male) | 2 | 1,773 | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Age of household head (ref = > 40 years) | 2 | 1,773 | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Marital status of HH (ref = married) | 1 | 450 | 1.59 (0.07–33.33) | 1 | NS | NS | Marginal |

| ◦ Education (ref = at least secondary educ.) | 2 | 1,773 | 0.98 (0.96–1.02) | 1 | NS | NS | Marginal |

| ◦ Employment status (ref = employed) | 1 | 450 | 3.85 (0.38–43.48) | 1 | NS | NS | Marginal |

| ◦ Presence of elderly persons in household | 0 | 1 | NS | NS | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Health facility type (ref = public) | 1 | 450 | 0.73 (0.24–2.22) | 1 | 452 | 6.50 (2.60–15.80) | Marginal |

| ◦ Health facility level (ref = primary care) | 1 | 450 | 3.19 (1.00–10.16) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Hospitalization | 0 | 1 | 452 | 10.80 (5.40–24.80) | Significant | ||

| ◦ Intensive care unit (ICU) admission | 0 | 1 | 280 | 1.81 (0.73–1.51) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Length of hospital stay | 0 | 1 | 280 | 1.04 (0.99–1.08) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Emergency/unplanned surgery | 0 | 1 | 280 | 5.76 (2.14–15.54) | Significant | ||

| ◦ Religion (ref = Christian) | 1 | 450 | 2.59 (0.54–12.42) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| HIV/AIDS, TB, HBV, and HCV | |||||||

| ◦ Residence (ref = urban) | 1 | 3,151 | 1.75 (1.36–2.26) | 3 | 41,659 | 0.83 (0.32–2.14) | Marginal |

| ◦ Socio-economic status (ref = wealthiest) | 4 | 6,602 | 1.79 (0.19–17.03) | 4 | 42,111 | 1.57 (0.40–6.25) | Marginal |

| ◦ Household size | 0 | 1 | 1,190 | 0.73 (0.66–0.81) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Insurance status (ref = insured) | 1 | 1,006 | 2.70 (1.10–6.70) | 3 | 41,659 | 0.96 (0.44–2.12) | Marginal |

| ◦ Social safety net (benefits, vouchers, etc.) | 1 | 1,267 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Sex of the patient (ref = male) | 1 | 3,151 | 0.97 (0.77–1.23) | 4 | 42,111 | 1.04 (0.58–1.88) | Marginal |

| ◦ Married status of patient | 1 | 3,151 | 0.53 (0.45–0.64) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Age of head of household | 0 | 1 | 2,969 | 1.00 (0.01–1.10) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Education (ref = at least secondary educ.) | 0 | 3 | 4,611 | 1.74 (0.62–4.85) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Employment status (ref = employed) | 1 | 1,267 | 1.06 (0.87–1.29) | 2 | 38,690 | 1.34 (1.12–1.60) | Marginal |

| ◦ Elderly household member | 0 | 1 | 452 | 3.90 (2.00–7.80) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Hospitalization | 1 | 1,006 | 30.60 (4.80–199.80) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Health facility type (ref = public) | 1 | 1,006 | 2.60 (1.50–4.30) | 1 | 452 | 2.90 (1.50–8.90) | Marginal |

| ◦ Decentralization of care | 1 | 3,151 | 0.53 (0.42–0.67) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ CD4 count (ref = ≥350) | 1 | 3,151 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 1 | 1,190 | 1.04 (0.51–2.11) | Significant |

| ◦ HIV and TB co-infection | 2 | 2,184 | 1.72 (0.55–5.36) | 1 | 452 | 3.10 (1.70–5.60) | Significant |

| ◦ Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis | 1 | 1,006 | 2.60 (1.80–4.00) | 0 | Significant | ||

| ◦ Duration on anti-retroviral therapy | 1 | 2,412 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1 | 1,190 | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | Marginal |

| ◦ Delay in diagnosis | 1 | 1,178 | 1.10 (0.70–1.80) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| Malaria | |||||||

| ◦ Residence (ref = urban) | 2 | 3,514 | 0.92 (0.78–1.08) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Socioeconomic status (ref = wealthiest) | 2 | 3,514 | 3.98 (0.15–108.22) | 1 | 1,350 | 13.00 (7.90–21.20) | Significant |

| ◦ Sex of household head (ref = male) | 1 | 2,164 | 1.08 (0.92–1.26) | 1 | 1,350 | 2.90 (1.20–6.90) | Marginal |

| ◦ Age of household head | 1 | 2,164 | 0.98 (0.93–1.05) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Education (ref = at least secondary educ.) | 1 | 2,164 | 0.96 (0.68–1.37) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Employment status (ref = employed) | 1 | 2,164 | 1.05 (0.86–1.29) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Health facility type (ref = public) | 2 | 3,514 | 2.34 (0.99–5.51) | 1 | 1,350 | 3.70 (2.50–5.50) | Significant |

| ◦ Distance to health facility | 1 | 2,164 | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Ownership of house (ref = owner) | 0 | 1 | 1,350 | 1.90 (1.30–2.80) | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Severe malaria | 0 | 1 | 1,350 | 3.60 (2.20–5.90) | Significant | ||

| Neglected tropical diseases | |||||||

| ◦ Residence (ref = urban) | 1 | 92 | 0.56 (0.08–3.33) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Socioeconomic status (ref = wealthiest) | 2 | 203 | 3.98 (0.76–20.93) | 0 | Significant | ||

| ◦ Insurance status (ref = insured) | 1 | 111 | 2.13 (0.10–44.80) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Sex of the patient (ref = male) | 1 | 92 | 0.67 (0.28–1.67) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Age of the patient | 1 | 92 | 1.20 (0.30–4.40) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Education status of the patient | 1 | 92 | 0.67 (0.12–1.25) | 0 | Marginal | ||

| ◦ Religion of the patient (ref = Christian) | 1 | 92 | 2.60 (0.40–15.9) | 0 | Marginal | ||

Abbreviations: UVD: Uncomplicated vaginal delivery. NS: Not significant.

Table 5. Study characteristics and main findings of included qualitative studiesa (n = 7).

| Study Country | Qualitative methods | Participants sample size | Study objectives | Main findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | Data Analysis | ||||

| Botman et al. 2021 Tanzania |

Observation, discussion groups, and unstructured interviews | Grounded theory | 67 | To investigate patients’ access to surgical care for burns in terms of timeliness, surgical capacity, and affordability in a regional referral hospital in Manyara, Tanzania | * Hospitalization induced CHE incidence, exceeding CHE threshold by up to 6 times for contracture patients and up to 15 times for acute burn wounds patients. * Despite accepting hospital fees in instalments, patients faced debts that became large burden for the families involved. * Common coping mechanism was selling land and animals, assets, as well as rely on neighbours to feed their children. |

| Chabrol et al. 2019 Cameroun |

Individual in-depth interviews | Grounded theory | 12 | To appraise patients’ and healthcare professionals’ (HCP) experiences with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) diagnosis and care, with respect to diagnosis, counselling, access to care and treatment, and the infections’ impacts on social and economic trajectories of patients in Yaoundé, Cameroun | * Access to care and treatment for HBV and HCV infection depends on patients’ capacity to pay for these expensive tests * For HBV and HCV patients who do pay for these screenings, the consequences on their social and economic life trajectories are catastrophic. * Patients with HIV-HBV co-infection experienced less barriers to accessing treatments as their HIV antiretroviral treatment (tenofovir) was also effective for HBV. Others experienced OOP payments that were insurmountable barriers to access care. * The OOP expenditures required for treatment impacted detrimental financial consequences including debts, selling assets, and relying on financial support of social network. |

| Ibukun & Adebayo 2020 Nigeria |

Individual in-depth interviews | Discourse analysis | 27 | To assess the level of poverty among those with NCDs, the OOP expenses incurred on NCDs while considering the probability of NCDs inducing CHE and impoverishment |

* NCDs induce CHE and leads to impoverishment particularly for households in the lowest socio-economic quintile. * Health insurance reduced the probability of CHE incidence from NCDs healthcare. |

| Ntambue et al. 2019 Congo, Democratic Republic |

Semi-structured individual interviews | Content analysis | 58 | To identify risk factors for CHE incidence associated with obstetric and neonatal care in Lubumbashi, Congo DR. |

* Hospitalization cost for obstetric and neonatal care–unknown at admission–were a great burden which the household struggle with. * CHE incidence was higher among poor households, maternal or neonatal complications, and involved specialist care * Inability to meet hospitalization costs lead to incarceration of mothers and newborn, and impoverishment |

| Nwanna-Nzewuna et al. 2021 Uganda |

Semi-structured individual interviews | Grounded theory | 546 | To determine the societal cost of surgical care delivery and its drivers; to ascertain the prevalence of CHE incidence and medical impoverishment among surgical patients at Soroti Regional Referral Hospital (SRRH), Uganda and their households; and to elucidate the impact of surgical hospitalization on patients and their households |

* Hospitalization induced severe financial catastrophe and impoverishment for the households * Lost income-earning opportunities complicates family finances during surgical hospitalization. |

| Obembe & Fonn 2020 Nigeria |

Individual in-depth interviews | Inductive (reasoning) analysis | 31 | To explore the lived experiences of people admitted for a recent emergency surgical procedure in selected hospitals in Ibadan, Nigeria with a specific focus on both slum and non-slum dwellers | * Health insurance coverage and social health insurance participation was very low * CHE incidence and inability to pay leads to delayed or poor-quality care, humiliation, and incarceration * CHE incidence and inability to pay is worse among low-income households |

| Onarheim et al. 2018 Ethiopia |

Individual in-depth interviews (IDI) and focus-group discussions (FGD) | Content analysis | 41 IDIs and 7 FGDs | To explore intra-household resource allocation, focusing on how families prioritize newborn health and household needs in Ethiopia; and to explore coping strategies families use to manage these priorities. | * Even though child and maternal health services are supposed to be provided free of charge at the health center level, families still suffer CHE incidence for newborn care at the hospital. * Families are forced to choose between potential worsening of the baby’s health on the one hand, and risking unbearable newborn healthcare costs or financial consequences for the family when taking the newborn to hospital * The poorest households are most faced by CHE incidence from newborn care, with little or no coping mechanism |

aOnly findings from qualitative analysis were reported here. Quantitative data in mixed methods studies were included meta-analysis and narrative synthesis.

Table 6. Themes, subthemes and number of contributing statements and studies with examples of supporting statements from qualitative studies.

| Theme | Subtheme | Statements (n) | Studies (n) | Examples of supporting statements with citation number of contributing study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low socioeconomic status | Poor households faced financial barriers to accessing healthcare | 13 | 5 |

“The speed with which patients get care depends on the head of the family’s pocket” [36] “The problem we have with hepatitis B is the exorbitant cost of the assessment for patients, who are most often students and cannot afford to pay, so we can’t follow them.” [36] “The drugs I am asked to buy cost between 6000 and 7000 (about $20 and $24). Just drugs! Sometimes it may not even last me for the whole month. As a pensioner who retired from a state where our pension has not been paid for so long, it is serious. Even though it is not supposed to be big money if the economy was good and things are normal, but in truth, this is where we have found ourselves” [51] a “Since I had no money to go to the health center, when my daughter fell ill, I went to get, on credit, malaria medications from the pharmacy of my friend’s little brother.” [77] “…Yes, I was delayed because of money problem so I was a bit delayed” [81] “If I go to the hospital with my child, there is no one who can properly give food for the others, there is no one to wash them or send them to school properly. They will not go to school and also there will be no one to buy them books.” [87] |

| Poor households that access care face financial catastrophe | 11 | 5 |

“We sold our land (USD 805) to access treatment” [79]. “Another said, “We sold food stuff (USD 54), 2 goats (USD 97), a bull (USD 258), a pig (USD 43)” [79] “I had asked the nurses to keep my baby if they wanted, and to let me go look for money until I could pull together the necessary sum.” [77] |

|

| Lost income-earning opportunities complicates access to care | 8 | 3 |

“Since I was in the hospital, I couldn’t trade, and I couldn’t help my husband: everything was screwed [messed up]. On his own, he had to pay for everything: food, school fees, transportation, clothes, etc. In these conditions, that’s how we didn’t have money to pay for health care.” [77] “Let us say a person has an ox with which he farms his land. If he sells this ox to be able to pay for treatment for his child, he will have nothing to fend his family with. …” [87] “I went crying to my older sisters. They gave me money to open a small business. I spent everything to pay for the exams. Now I am here with no money (…)” [36] |

|

| Not having health insurance | Health insurance coverage is low | 7 | 3 |

“Only a few people benefit from insurance schemes—like civil servants, or people whose employers have an insurance scheme—and have access to this programme (for pre-therapeutic assessment), but they still have to pay for the injections.” [36] “Quite a number of people here are not extremely poor because healthcare in Nigeria is not cheap. The extreme poor will not come to the hospital because insurance is minimal, although some may come when it is life-threatening.” [51]. |

| Health insurance enrolment should be encouraged | 5 | 3 |

“Health insurance makes a lot of things cheap for me. I collect the drugs at almost no cost, even when I pay 1000, it doesn’t even matter because I know the drugs that I am given cost much more than that. The other day, they didn’t have the drugs I wanted, when I got to a pharmacy outside and I bought it with my money, then I realized I how much I have been enjoying.” [51] “It is supposed to be available for everybody, not government workers alone. We are all Nigerians, so NHIS should be available for everybody” [81] |

aCurrency converted to US Dollars using the prevailing exchange rate at the time of study

Population-level factors

Household characteristics

Household characteristics that are associated with CHE incidence include residence [16, 20, 21, 28, 39, 41, 43, 45, 46, 50, 52, 56, 58, 62–65, 67, 68, 73–76, 78, 91–94, 98, 99, 103], socioeconomic status [16, 17, 21, 25–28, 34, 35, 39, 41, 43, 45, 46, 50, 52, 53, 55, 56, 58, 59, 62, 63, 65–68, 73, 75, 83, 91–93, 95, 98, 99, 103, 104], household size [17, 20, 21, 25, 26, 28, 34, 39, 41, 43, 45, 50, 53, 58, 62, 63, 65, 66, 68, 73, 75, 76, 83, 92, 93, 95, 98, 99, 104], health insurance status [17, 18, 21, 23, 26–28, 39, 44, 46, 47, 52, 53, 59, 62, 64, 66, 74–76, 83, 92, 94], social safety recipient [27, 35, 38], and marginalization status [28]. Meta-analysis of comparable studies suggests that only socio-economic status (10% THE: OR = 1.99 (95% CI = 1.32–2.98) and 40% NFE: OR = 3.02 (95% CI = 2.23–4.08)) and household size (10% THE: OR = 1.07 (95% CI = 1.02–1.13) and 40% NFE: OR = 1.06 (95% CI = 1.00–1.12)) were significantly associated with CHE incidence (Table 3).

Rural households are at a particularly high risk of catastrophic costs. A multi-country World Health Survey showed that “households living in urban areas consistently seemed to be better protected against catastrophic health expenditure” than rural households [91]. Rural residence, combined with distance to health facilities, increases rural households’ exposure to financial catastrophe[52].

The poorest households were at a higher risk of CHE than richer households [28, 43, 46, 51, 53, 81, 87, 91], as the following statement from a respondent reflects:

“I got treatment for my first child from the hospital, and they charged us a lot of money. We did not have anything left after, and my husband was hiding. After a long time, we were able to borrow money from a relative…” [87]

Health insurance coverage and social safety nets both protect households from CHE, although quantitative analysis suggests this protection is inconsistent.

“Health insurance makes a lot of things cheap for me. I collect the drugs at almost no cost, even when I pay 1000, it doesn’t even matter because I know the drugs that I am given cost much more than that. The other day, they didn’t have the drugs I wanted, when I got to a pharmacy outside and I bought it with my money, then I realized I how much I have been enjoying” [51].

Household head factors

Several studies reported the relationship between CHE incidence and the sex/gender [17, 21, 28, 34, 35, 39, 41, 43, 45, 50, 52, 55, 56, 58, 62, 63, 65–68, 73, 75, 76, 78, 91–93, 95, 98, 99, 103, 104], age [17, 25, 28, 34, 35, 39, 43, 46, 50, 52, 58, 65–68, 75, 76, 92, 95, 104], marital status [20, 39, 43, 45, 62, 63, 76, 78, 92, 93, 95, 98, 104], education status [17, 20, 21, 26, 34, 39, 43, 45, 50, 56, 62, 63, 65–67, 73, 75, 76, 78, 91–93, 95, 99, 103, 104], and employment status [17, 21, 28, 35, 39, 43, 45, 46, 50, 52, 56, 62, 63, 67, 73, 75, 76, 78, 92, 95, 104] of the household head. Of these factors, only the employment status was significantly associated with CHE incidence (Table 3). In settings without universal insurance coverage, when the household head (who are often the main, or even the only, income earner) is unable to work due to own or a family member’s illness, the combination of lost income and health expenses is devastating [81, 87]. Also, households headed by a retiree were particularly at high risk of CHE incidence, as high as 75% [28, 78].

Household members factors

CHE incidence was significantly associated with advanced age [17, 21, 26, 28, 39, 41, 43, 45, 50, 52, 56, 62, 63, 65, 68, 73, 75, 78, 83, 91–93, 98, 103], chronic illness [21, 25, 26, 28, 34, 39, 45, 56, 62, 67, 68, 74–76, 83, 92, 93, 95, 99], and hospitalization [17, 25, 27, 41, 52, 58, 62, 68, 83, 94, 103, 104]; but not associated with presence of children < 5-years of age [21, 35, 39, 41, 43, 45, 50, 62, 63, 65, 66, 68, 73, 75, 83, 91, 98], women of child-bearing age [50], disability [17, 34, 65, 66, 91, 98, 99], or obesity [39] in the household (Table 3). Tobacco smoking increased the likelihood of CHE incidence (OR = 1.11 (95% CI = 1.10–1.12)) [16].

Health system factors

Several studies evaluated the link between CHE incidence and the level of health facility were care was sought [25, 35, 45, 56, 67], health facility type [17, 21, 25, 35, 39, 45, 52, 56, 68, 73, 75, 93, 94], distance to health facility [41, 46, 56, 58, 62, 65, 67, 68, 93], number of health facilities in district/county [28], and prior care from traditional healers [27, 34]. Of these, health facility type, and health facility level were significantly associated with CHE incidence–Table 3. A few studies, however, showed that accessing care from private healthcare providers decreased households’ risk of catastrophic expenditure, although the level and type of care sought from these providers was not clear [21, 52, 93].

Other factors

Other marginal factors linked with CHE incidence at the population level include violence against women [34], house ownership [46], business ownership [35], and regular use of mosquito bed nets [17, 52]–Table 3.

Disease-specific determinants

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs)

NCDs significantly increased households’ likelihood of incurring CHE. Cancer increased the likelihood of a household incurring CHE by 7.6%, diabetes 3.5%, TB 3.4%, hypertension 1.9%, and other cardiac diseases by 0.9%. Overall, having a chronic diseases member in a household increased the likelihood of CHE incidence by 2.2% [80]. For households affected by NCDs, CHE incidence was significantly associated with poor socioeconomic status [48, 49, 51, 57, 80, 96, 100, 101], employment status [51, 57, 80, 96, 100, 101], old age [48, 49, 51, 80, 96], and disability [48]. However, household head’s sex [48, 49, 51, 57, 71, 80, 101], marital status [51, 57, 71, 80, 96, 101], education status [48, 49, 51, 57, 71, 80, 101], employment status [51, 57, 80, 96, 100, 101], household residence [48, 49, 57, 71, 80, 100, 101], and religion [101] were not associated with CHE incidence (Table 4). Having health insurance was protective of catastrophic costs [51, 71, 80]–as in the population level.

Reproductive, neonatal, and child healthcare

For households that sought reproductive, newborn, and child healthcare, CHE incidence was linked to household residence [22], socioeconomic status [38, 42, 77], household size [42], health insurance [42], education status [22, 30, 42], employment status [38, 42], health facility level [77], type of healthcare provider [77], distance to health facility [22], pre-natal illness/hospitalization [77], complicated delivery [77], HIV+ pregnancy [42], and neonatal admission [77]–Table 4. Of these, household residence, socio-economic status, insurance status, household head employment status, pre-natal hospitalization, delivery complications, and neonatal admission were significantly associated with CHE incidence.

“I had asked the nurses to keep my baby if they wanted, and to let me go look for money until I could pull together the necessary sum.” [77]

“I got treatment for my first child from the hospital, and they charged us a lot of money. We did not have anything left after, and my husband was hiding. After a long time, we were able to borrow money from a relative…” [87]

Surgery and trauma care

For households that sought surgical or trauma care, CHE incidence was associated with residence, socioeconomic status, health insurance status, and sex, age, marital status, education, and employment status of household head–Table 4. Other factors include old age, hospitalization, healthcare provider type, specialist care, intensive care unit admission, and emergency surgery [31, 40, 79, 81, 82, 84, 89, 90].

“…all my family ran away because of the [surgical] expenses‥” [81]

Chronic infectious disease (HIV, TB, HBV, and HCV)

CHE incidence for households that sought healthcare for HIV, TB, HBV, and HCV infections was linked to 19 sociodemographic and health system factors [24, 29, 32, 33, 36, 38, 61, 69, 72, 80, 102] (Table 4). Of these, socioeconomic status [24, 29, 38, 69, 72, 80, 102], health insurance [24, 29, 72, 80], employment status [29, 36, 38], hospitalization [24, 102], healthcare provider type [24, 102], HIV-TB coinfection [24, 69, 102], and extra-pulmonary TB [24] were significantly associated with CHE incidence. Notably, while HIV care decentralization improves equity in access to ART, it does not fully remove the risk of CHE, unless other innovative reforms in health financing are implemented [33]. While HIV patients’ healthcare is largely subsidized, the costs of TB, HBV, HCV care are mostly borne directly by the patients. Therefore, the latter households face significantly higher risks of CHE [36, 61, 80].

Malaria

The included studies identified six sociodemographic factors—household residence, socioeconomic status, household head’s sex, age, education, and employment status—and two health system factors: healthcare provider type and distance to the health facility [54, 97]. Of these, only socioeconomic status was significantly associated with CHE incidence for malaria treatment (Table 4).

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs)

For households that sought healthcare for NTDs, seven socio-demographic factors—household residence, socio-economic status, health insurance, and the sex, age, education, and religion of the patients—were linked with CHE incidence [37, 85] (Table 4). Of these factors, only socioeconomic status was significantly associated with CHE incidence.

Discussion

Factors associated with CHE incidence among SSA households are multidimensional and diverse. Overall, a few points emerge from this review. First, the majority of included studies used regression analysis to evaluate the factors associated with CHE incidence. Given that included studies utilized different definitions for evaluated factors, meta-analysis was possible for fewer included studies. However, all included studies were evaluated and synthesized narratively. Secondly, studies evaluating CHE incidence in SSA countries mostly used the ‘capacity-to-pay’ or ‘non-food expenditure’ definition while fewer studies used the ratio of OOP to total household income [7]. However, studies that used both definitions suggests that CHE-associated factors were largely similar between the definitions [19, 21, 30, 60, 68, 78, 92, 93]. Reporting CHE incidence and CHE-associated factors using both definitions enhances comparability between studies. Also, despite the progress SSA countries have made towards universal health insurance, households are still exposed to CHE [46, 66, 84]. Yet, it is likely that many low-income uninured households in SSA countries without universal insurance choose not to seek health care rather than face the financial hardship associated with out-of-pocket healthcare payments [46, 51, 99].

At the population level, our review highlights rural residence, low socioeconomic status, lack of health insurance, advanced age, chronic illness, hospitalization, utilization of private healthcare provider, and utilization of specialist care as the most significant determinants of CHE incidence. Our findings are consistent with findings in comparable regions such as Southeast Asia [105, 106] and South America [107, 108]. Due to widespread poverty, most SSA households cannot afford insurance premiums and so rely on OOP payment for healthcare [2, 109]. Given the highly regressive impact of OOP payment [2, 3], most studies in SSA region demonstrate households’ socioeconomic status as a risk factor for CHE [3, 109]. Rural residence in SSA countries is a proximal indicator of limited household income [50, 91, 103]. This is compounded by lack of health facilities in the rural settings, transportation costs to reach urban health facilities, or the indirect expenditure, such as the costs incurred by an accompanying caretaker[20, 21, 76, 91]. Having an elderly person in the household increases the chances of incurring CHE [21, 26, 63, 103]. This is as expected because elderly persons require more healthcare [21], and are more likely to have chronic illnesses [26, 28]. Both factors increase health expenditures and often require working family members to quit their jobs. Hospitalization, utilization of private healthcare provider, and/or specialist (tertiary) healthcare all increase the possibility of incurring CHE [25, 41, 62, 75, 94]. Given that most SSA countries do not have financial risk protection mechanisms in place, this situation is even grim as the CHE definitions used in included studies does not consider households with unmet healthcare needs.

Factors distinctly associated with CHE incidence at the disease-specific level include disability in a household member for NCDs; severe malaria, blood transfusion, and distant health facilities for maternal and child health services; emergency/unplanned surgery for surgery and trauma patients; and low CD4 count, HIV and TB co-infection, and extra-pulmonary TB for HIV and TB patients. For households affected by NCDs, disability imposes further financial burden in the form of extra health expenses and lost income [51]. The farther the distance of health facilities from the place of residence, the higher the direct non-medical costs, including transportation and accommodation costs. Hence, rural households are therefore more likely to incur CHE for maternal and child healthcare [22, 97]. For similar reasons, blood transfusion and severe malaria treatments are rarely available at rural health facilities, and require hospitalization and specialist care–which increase CHE risks [22, 54]. For patients requiring HIV and TB care, low CD4-count, HIV and TB co-infection, and extra-pulmonary TB are all indicative of poor health status requiring increased usage of healthcare services with a higher risk of incurring CHE [24, 29, 102].

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to comprehensively map the factors associated with CHE incidence in SSA. We also identified determinants for both population and disease-specific level CHE incidence which enables easy identification of populations that are most at risk for community-wide and/or vertical disease-specific interventions. Furthermore, our review combined both quantitative and qualitative studies to synthesize evidence that is both generalizable and sufficiently nuanced.

Our study has a few limitations. First, our review does not capture factors associated with households who cannot meet treatment costs–a gap that future studies can address using new variables that capture these households. Also, as we identified determinants of CHE incidence using two thresholds, we may have missed some factors that might have been reported using other thresholds. Thirdly, there is the inherent difficulty in mapping and adjudicating the evidence on these factors identified from the studies as either significant or marginal. Ultimately, these were subjective judgments based on the authors’ understanding of the texts in included studies that are not as error-proof as might be hoped for. To address this, a multi-rater system was used–each factor was independently adjudicated by at least two authors–to minimize subjectivity. Finally, our categorization of some determinants as marginal does not imply dismissal of the influence of these factors in some unique settings. In some settings and for different households, these “marginal” factors could have greater eminence.

Policy implications

Our review provides significant contextual evidence for policy discussion and health financing reforms by identifying the sociodemographic characteristics of households that are most likely to suffer financial catastrophe in SSA countries. This is a critical step toward developing comprehensive social protection mechanisms–a key vehicle for achieving UHC. Our study provides key details for fine-tuning the different means of identifying households for targeted or supplemental protection such as means testing, proximal means testing, geographic targeting, or participatory wealth ranking [109].

Conclusion

Our study suggests that the key factors associated with population and disease-specific CHE incidence in SSA countries are rural residence, low socioeconomic status, lack of health insurance, having an elderly household member, chronic illness, hospitalization, use of private healthcare providers, and use of tertiary/specialist healthcare. Highlighting these factors in a comprehensive review underscores potential strategies for implementing/improving financial risk protection measures to achieve UHC in these SSA countries.

Supporting information

Search period was from 01 January 1990 to 31 December 2021.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(TIF)

(DOC)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Universal Health Coverage (UHC) [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/universal-health-coverage#tab=tab_1

- 2.Ponsar F, Tayler-Smith K, Philips M, Gerard S, Van Herp M, Reid T, et al. No cash, no care: How user fees endanger health-lessons learnt regarding financial barriers to healthcare services in Burundi, Sierra Leone, Democratic Republic of Congo, Chad, Haiti and Mali. Int Health [Internet]. 2011;3(2):91–100. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.inhe.2011.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saksena P, Hsu J, Evans DB. Financial Risk Protection and Universal Health Coverage: Evidence and Measurement Challenges. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9). doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagstaff A, Flores G, Hsu J, Smitz MF, Chepynoga K, Buisman LR, et al. Progress on catastrophic health spending in 133 countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Glob Heal. 2018;6(2):e169–79. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30429-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ifeagwu SC, Yang JC, Parkes-Ratanshi R, Brayne C. Health financing for universal health coverage in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Glob Heal Res Policy. 2021;6(1). doi: 10.1186/s41256-021-00190-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagstaff A, Neelsen S. A comprehensive assessment of universal health coverage in 111 countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Glob Heal. 2020;8(1):e39–49. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30463-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eze P, Lawani O, Agu J, Acharya Y. Catastrophic health expenditure in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2022;100(5):337–51. doi: 10.2471/BLT.21.287673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbour RS. The case for combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in health services research. J Heal Serv Res Policy. 1999;4(1):39–43. doi: 10.1177/135581969900400110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews [Internet]. Vol. 1. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme; 2006. b92 p. Available from: https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339(7716):332–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 11]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- 13.Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.1 [updated September 2020]. Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, et al., editors. Cochrane. Cochrane; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riley RD, Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. Bmj. 2011;342(7804):964–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(45). doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adeniji F, Lawanson O. Tobacco use and the risk of catastrophic healthcare expenditure. Tob Control Public Heal East Eur. 2018;7(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adisa O. Investigating determinants of catastrophic health spending among poorly insured elderly households in urban Nigeria. Int J Equity Health [Internet]. 2015;14:79. Available from: doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0188-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aidam PW, Nketiah-amponsah E, Kutame R. The effect of health Insurance on out-of-pocket payments, catastrophic expenditures and healthcare utilization in Ghana: Case of Ga South Municipality. J Self-Governance Manag Econ. 2016;4(3):42–65. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akazili J. Equity in health care financing in Ghana. The University of Cape Town; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akinkugbe O, Chama-Chiliba CM, Tlotlego N. Health Financing and Catastrophic Payments for Health Care: Evidence from Household-level Survey Data in Botswana and Lesotho. African Dev Rev. 2012;24(4):358–70. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aregbeshola BS, Khan SM. Determinants of catastrophic health expenditure in Nigeria. Eur J Heal Econ. 2018;19(4):521–32. doi: 10.1007/s10198-017-0899-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arsenault C, Fournier P, Philibert A, Sissoko K, Coulibaly A, Tourigny C, et al. Emergency obstetric care in Mali: catastrophic spending and its impoverishing effects on households. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(3):207–16. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.108969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]