Abstract

Purpose

Our purpose was to characterize radiation treatment interruption (RTI) rates and their potential association with sociodemographic variables in an urban population before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods and Materials

Electronic health records were retrospectively reviewed for patients treated between January 1, 2015, and February 28, 2021. Major and minor RTI were defined as ≥5 and 2 to 4 unplanned cancellations, respectively. RTI was compared across demographic and clinical factors and whether treatment started before or after COVID-19 onset (March 15, 2020) using multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results

Of 2,240 study cohort patients, 1,938 started treatment before COVID-19 and 302 started after. Patient census fell 36% over the year after COVID-19 onset. RTI rates remained stable or trended downward, although subtle shifts in association with social and treatment factors were observed on univariate and multivariate analysis. Interaction of treatment timing with risk factors was modest and limited to treatment length and minor RTI. Despite the stability of cohort-level findings showing limited associations with race, geospatial mapping demonstrated a discrete geographic shift in elevated RTI toward Black, underinsured patients living in inner urban communities. Affected neighborhoods could not be predicted quantitatively by local COVID-19 transmission activity or social vulnerability indices.

Conclusions

This is the first United States institutional report to describe radiation therapy referral volume and interruption patterns during the year after pandemic onset. Patient referral volumes did not fully recover from an initial steep decline, but local RTI rates and associated risk factors remained mostly stable. Geospatial mapping suggested migration of RTI risk toward marginalized, minority-majority urban ZIP codes, which could not otherwise be predicted by neighborhood-level social vulnerability or pandemic activity. These findings signal that detailed localization of highest-risk communities could help focus radiation therapy access improvement strategies during and after public health emergencies. However, this will require replication to validate and broaden relevance to other settings.

Introduction

Public health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (eg, social distancing and local “stay at home” orders) and patient treatment avoidance severely compromised cancer care in the United States (US)1 and abroad.2 There has been well-documented deferment of cancer screenings and diagnoses since the beginning of the pandemic as well as significant reduction in cancer-related clinical encounters among patients actively on treatment.3, 4, 5 A British study leveraging the United Kingdom Health Data Research Hub for Cancer registry to survey changes in cancer service utilization and outcomes during the early pandemic demonstrated an increase in cancer-related deaths independent of COVID-19 infection during the first pandemic year.6 Given ongoing waves of variant-driven pandemic spread, there remains urgent need to balance prevention of infection while maintaining cancer treatment continuity and quality.

Unplanned interruption of daily radiation therapy (RT) disproportionately affects marginalized populations.7 Expected survival outcomes incrementally decrease with each day of interruption.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Because the pandemic broadly handicapped cancer treatment quality measures, we wished to inquire whether COVID-19 widened baseline RT access disparities.7 , 17 This is particularly relevant to the Southeastern US, where COVID-19 transmission rates have led the nation.18

Reliable characterization of RT interruption (RTI) rates in the United States during the pandemic remains unavailable. A published survey of national radiation oncology practice leaders sponsored by the American Society of Radiation Oncology suggested that patients have presented to community-based care with more advanced stage disease and have experienced frequent treatment interruptions during the pandemic.19 Early international series from acutely affected centers in Asia20 , 21 and Italy22 , 23 reported abrupt increases in RTIs and access delays in spring 2020, but these experiences were not supplemented by longitudinal follow-up. A more recent series from India24 suggested higher RTI rates during COVID-19 at a tertiary center because of government-instituted transportation “curfews,” although the study cohort was limited to 76 patients with head and neck cancer. The intent of this report was to compare RTI rates in a metropolitan population treated before and after onset of the pandemic at a US academic center over a calendar year and to characterize associations between RTI, clinical factors, patient demographics, and home neighborhood location.

Methods and Materials

Patient population

Institutional review board approval (#16-04888-XP and #20-07287-XM) was granted to retrospectively review electronic health records (EHRs) for all patients treated with RT at our academic inner urban safety-net hospital practice from January 1, 2015, to March 14, 2020, for prepandemic benchmarking, and March 15, 2020, to February 28, 2021, after the recognized onset of COVID-19 in our city. Patients whose treatments spanned the March 15, 2020, cut point were included in the pre–COVID-19 cohort. Due to a turnover in medical school-hospital partner affiliation and radiation oncology EHR systems, complete records were not available for all patients treated from January 2018 to May 2019. This interval was excluded from analysis. Patients who did not initiate treatment at our facility were also excluded from study.

Outcome measures

RTI was defined as an unplanned treatment cancellation or patient “no-show.” Our primary outcome measure was major RTI, defined as greater than or equal to 5 interruptions during the prescribed course of treatment. Minor RTI was defined as 2 to 4 RT schedule interruptions. Scheduled interruptions occurring on a day the clinic was closed (ie, holidays) were not counted. Only interruptions occurring after the start date of treatment were included for analysis.

Data collected

Clinical and treatment information in addition to demographic information such as patient residence addresses were collected. Patient addresses were used for mapping at the ZIP code level to maintain patient privacy. For health insurance status, patients were categorized as either uninsured or enrolled in Medicaid versus patients insured commercially or with Medicare without dual coverage status. Predicted income was categorized as low, middle, or high using 2020 US Census data for patient's home address ZIP code (<$34,000, $34,001 to $67,000, and >$67,000, respectively). Distance from patient's residence to the RT facility was calculated using the patient's address.

Statistical analysis

Significance of differences in distribution of patient characteristics between treatment eras was examined with χ2 testing. We tested for differences between 2 Poisson rates25 to determine significance of decreases in patients starting RT for each calendar month, as well as changes in distribution of disease site presentations after the start of COVID-19 versus baseline data from the prior cataloged year. We adjusted for multiplicity in testing by Bonferroni correction: P = .05/12 = .0042 for monthly starts (controlling for a family-wide error rate at 5%) and P = .05/10 = .005 for each of 10 site categories. Major and minor RTI rates were calculated according to timing of any treatment given relative to the beginning of the local COVID-19 public health emergency on March 15, 2020. Frequencies of variables were calculated according to RTI status and treatment timing. Multivariable logistic regression models were built to determine the effect of each variable on interruption rates in each era. Our modeling strategy used a stepwise process to adjust the effect of variables on interruption rates in terms of population characteristics. Variables were retained in the model using a variable inclusion threshold P value of < .1 on Wald's test.

The effect of timing relative to the pandemic on each variable was also investigated with multivariable logistic regression models, which included an interaction term between treatment period (before or during COVID-19) and each variable. This model was defined as

The effect of treatment period in different categories of each variable was tested with the interaction effect of treatment period and variable. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals were reported. Statistical analyses were conducted with R Studio (version 1.2.5033) software, with P values <.05 being considered statistically significant.

Geospatial analysis

Frequency of RTI was mapped at the level of residence ZIP codes and stratified according to patient race and insurance status. Mapping was performed with RStudio version 1.3.959 (PBC, Boston, MA) using the geospatial (GIS) package ggmap. Spatial visualization was performed with the GIS package ggplot2. Individual COVID-19 test results were geocoded by self-reported patient home address from a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)–compliant institutional COVID-19 testing registry (#20-07287-XM) managed by the senior author, which collected data from all local health department-supported outpatient COVID-19 testing. Social vulnerability index (SVI)26 and COVID-19 transmission mapping were performed with ArcGIS Pro version 2.8.6 (Redlands, CA), using data obtained from our COVID-19 registry as well as the current subscription version of the national PolicyMap database.27 The SVI data set included rank (categorical) and score (continuous) data. SVI rank has been used for data visualization, whereas SVI score has been used in GIS statistical analysis. Because the SVI data set is available at either census tract or county level, SVI ranks and scores for each ZIP code in the study area were estimated from census tract level data by land-area based geoimputation method.28 ZIP codes containing ≥50% “moderate” or “high” SVI US Census tracts were designated as “high SVI.” Local bivariate relationship (LBR) analysis was used to test for spatial association between RTI, COVID-19 incidence, and estimated SVI score distribution within our study area. LBR tests whether 2 variables share a statistically significant relationship throughout the space using local entropy.29 P values were calculated through a permutation test with α = .05 as the level of statistical significance. The false discovery test was used to account for multiple testing. Mean P values were also calculated by the LBR statistics to show whether there were statistically significant relationships between the variables throughout the study area. LBR analysis was performed with ArcGIS Pro.30

Results

Study cohort

A total of 2,240 patients received RT at our center and were included for analysis. Before March 15, 2020, 1,938 patients started treatment, and the remining 302 patients began treatment afterward. Descriptive cohort characteristics across prepandemic and COVID-19 periods are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Study cohort characteristics

| Total | Pre–COVID-19 era | COVID-19 era | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Total patients | 2240 (100) | 1938 (86.5) | 302 (13.5) |

| Sex | P = .90 | ||

| Female | 1172 (52.3) | 1013 (52.3) | 159 (52.7) |

| Male | 1068 (47.7) | 925 (47.7) | 143 (47.4) |

| Age (mean, y) | P = .61 | ||

| <65 | 1380 (61.6) | 1198 (61.8) | 182 (60.3) |

| ≥65 | 860 (38.4) | 740 (38.2) | 120 (39.7) |

| Race | P = .31 | ||

| Black | 1281 (57.2) | 1098 (56.7) | 183 (60.6) |

| White | 827 (36.9) | 725 (37.4) | 102 (33.8) |

| Unknown | 109 (4.8) | 97 (5.0) | 12 (4.0) |

| Other race | 23 (1.0) | 18 (0.9) | 5 (1.7) |

| Marital | P < .01* | ||

| Married | 879 (39.2) | 773 (39.9) | 106 (35.1) |

| .Single | 595 (26.6) | 525 (27.1) | 70 (23.2) |

| Widowed | 253 (11.3) | 258 (13.3) | 53 (17.6) |

| Divorced | 305 (13.6) | 200 (10.3) | 47 (15.6) |

| Separated | 105 (4.7) | 90 (4.6) | 15 (5.0) |

| Unknown | 30 (1.3) | 19 (1.0) | 11 (3.6) |

| Predicted annual income | P = .32 | ||

| Low (<$34,000) | 821 (36.7) | 704 (36.3) | 117 (38.7) |

| Middle ($34,000-$67,000) | 938 (41.9) | 807 (41.6) | 131 (43.4) |

| High ($67,000) | 255 (11.4) | 223 (11.5) | 32 (10.6) |

| Unknown | 226 (10.1) | 204 (10.5) | 22 (7.3) |

| Insurance type | P < .01* | ||

| Medicare | 940 (42.0) | 813 (42) | 127 (42.1) |

| Commercial | 840 (37.5) | 757 (39.1) | 83 (27.5) |

| At risk (Medicaid/no insurance) | 455 (20.3) | 364 (18.8) | 91 (30.1) |

| Other | 5 (0.2) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) |

| Fractions | P = .60 | ||

| 1-20 | 1044 (46.6) | 899 (46.4) | 145 (48.0) |

| >20 | 1196 (53.4) | 1039 (53.6) | 157 (52.0) |

| Diagnosis | P < .01* | ||

| Breast | 408 (18.2) | 341 (17.6) | 67 (22.2) |

| H&N | 338 (15.1) | 275 (14.2) | 63 (20.9) |

| Metastasis | 370 (16.5) | 319 (16.5) | 51 (16.9) |

| Lung | 271 (12.1) | 237 (12.2) | 34 (11.3) |

| Prostate | 169 (7.5) | 144 (7.4) | 25 (8.3) |

| GI | 199 (8.9) | 174 (9.0) | 25 (8.3) |

| GYN | 134 (6.0) | 122 (6.3) | 12 (4.0) |

| Hematologic | 99 (4.4) | 85 (4.4) | 14 (4.6) |

| CNS | 102 (4.6) | 99 (5.1) | 3 (1.0) |

| Other | 148 (6.6) | 140 (7.2) | 8 (2.7) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | - |

| Distance to RT in miles | P = .71 | ||

| 0-5 | 600 (26.8) | 507 (26.2) | 93 (30.8) |

| 5-10 | 613 (27.4) | 534 (27.6) | 79 (26.2) |

| 10-15 | 338 (15.1) | 292 (15.1) | 46 (15.2) |

| 15-20 | 104 (4.6) | 90 (4.6) | 14 (4.6) |

| 20-30 | 98 (4.4) | 84 (4.3) | 14 (4.6) |

| 30-40 | 78 (3.5) | 69 (3.6) | 9 (3.0) |

| >40 | 194 (8.7) | 169 (8.7) | 25 (8.3) |

| Unknown | 215 (9.6) | 193 (10.0) | 22 (7.3) |

| RT start month | P = .38 | ||

| Nonwinter (March-October) | 1440 (64.3) | 1239 (63.9) | 201 (66.6) |

| Winter (November-February) | 800 (36.7) | 699 (36.1) | 101 (33.4) |

P = P value from test for trend. Multivariable logistic regression model C-statistic = 0.71.

Abbreviations: CNS = central nervous system; GI = gastrointestinal; GYN = gynecologic; H&N = head and neck; RT = radiation therapy.

Statistically significant (Bonferroni-adjusted P < .0001).

For the full study population, median age was 61.8 years (19.7-95.7), and 1,172 (52%) subjects were female, similar across treatment periods. Our clinic serves a racial minority-majority population. Black patients constituted 57% (1,281) of the full cohort: 1,098 (57%) at baseline and 183 (61%) during the pandemic. There was no detectable population-level shift of patients from rural to urban neighborhoods close to our clinic; similar numbers of patients lived within 0 to 10 miles during the pandemic (57%) relative to before (54%). There were significant differences (P < .05) between baseline and pandemic cohorts in proportions of underinsured patients, married patients, and primary disease sites. Ninety-one (30%) patients treated during the pandemic were uninsured or enrolled on Medicaid versus 364 (19%) at baseline.

Patient census and case mix after onset of COVID-19

On-treatment patient census fell 49% the month immediately after onset of the pandemic and 36% over the first year of the pandemic. Fluctuating, incomplete recovery of patient referral volume was observed through to the spring of 2021 (Fig. 1 A). A significant reduction in the number of patients starting RT was observed during April (P = .004), June (P < .001), and October (P < .001) of 2020, all of which took place during local pandemic surges. A trend toward differences was seen for May (P = .01), July (P = .01), and September (P = .06) of 2020 and January of 2021 (P = .06). Total number of patients starting RT was significantly different between eras (P < .001). Distribution of primary disease site by COVID-19 era is presented in Fig. 1B. Significant differences were observed during COVID-19 in number of central nervous system (P < .001) and “other” primaries (P = .005). A trend toward differences was seen for breast (P = .01) and head and neck (P = .009).

Fig. 1.

(A) New patients starting radiation therapy by month, baseline versus COVID-19 era. (B) Disease site distribution by COVID-19 treatment era.

RT interruption rates before and during COVID-19

For the entire study cohort, 1,187 (53%) patients completed RT without interruption. Three hundred eighty-nine (17%) patients missed 1 appointment, 396 (18%) patients missed 2 to 4, and 264 (12%) missed 5 or more RT appointments. Mean RT interruption was 1.9 days (standard deviation [SD], 4) with a maximum of 42 days. The median number of missed appointments was 9 (mean, 10.7; SD, 6.5) and 2 (mean, 2.6; SD, 0.7) for patients who experienced either major or minor interruptions, respectively. Out of a total of 47,514 prescribed fractions, 46,334 (97.5%) treatments were delivered. At prepandemic baseline, 40,121 (97%) of 41,192 prescribed fractions were received. During the pandemic, 6213 (98%) out of 6,322 prescribed fractions were delivered.

RTI rates were incrementally lower during the pandemic (Table 2 ), although this remained nonsignificant for both major (OR, 0.73; 0.47-1.09; P = .14) and minor (OR, 0.81; 0.56-1.13; P = .23) interruptions. Association of baseline versus COVID-19–era treatment with potential RTI risk factors was modest (Tables E1 and E2). Before the pandemic, 1,357 (70%) patients completed RT with 0 to 1 interruption, 349 (18%) experienced 2 to 4 days of delay, and 232 (12%) patients had 5 or more interruptions. During COVID-19, 223 (73%) patients completed their radiation treatment with 0 to 1 interruption, 47 (16%) experienced 2 to 4 interruptions, and 32 (11%) were affected by major RTI during COVID-19. Of the 516 individual interruption events observed during COVID-19, 164 (32%) were due to a patient “no-show” versus 1,154 (31%) of the 3,738 total RTI events observed before the pandemic. From treatment records, only 1 patient was noted to have treatment interrupted directly by active COVID-19 infection. This was a patient receiving adjuvant RT, with the final week of treatment postponed 10 days by patient self-isolation.

Table 2.

RT interruption rates by patient characteristic

| Total |

Pre–COVID-19 era |

COVID-19 era |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor interruption (%) (2-4 RT breaks) | Major interruption (%) (5+ RT breaks) | Minor interruption (%) (2-4 RT breaks) | Major interruption (%) (5+ RT breaks) | Minor interruption (%) (2-4 RT breaks) | Major interruption (%) (5+ RT breaks) | |

| Overall | 20.0 | 11.8 | 20.5 | 12.3 | 17.4 | 10.6 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 19.7 | 11.9 | 20.2 | 12.3 | 16.6 | 8.8 |

| Male | 20.5 | 11.7 | 20.8 | 11.6 | 18.4 | 12.6 |

| Age (mean, y) | ||||||

| <65 | 22.4 | 14.0 | 23.1 | 14.2 | 18.2 | 12.6 |

| ≥65 | 16.5 | 8.3 | 16.5 | 8.4 | 16.2 | 7.5 |

| Race | ||||||

| Black or African American | 21.4 | 13.7 | 21.5 | 14.0 | 20.5 | 12.0 |

| White | 18.3 | 9.4 | 19.0 | 9.4 | 13.0 | 9.8 |

| Unknown | 20.6 | 6.5 | 21.1 | 7.2 | 16.7 | - |

| Other race | 10.0 | 13.0 | 13.3 | 16.7 | 0.0 | - |

| Marital | ||||||

| Married | 17.6 | 8.9 | 18.4 | 9.4 | 11.9 | 4.7 |

| Single | 21.9 | 14.6 | 23.0 | 15.4 | 14.1 | 8.6 |

| Widowed | 18.9 | 14.2 | 16.6 | 12.5 | 28.6 | 20.8 |

| Divorced | 24.8 | 10.2 | 24.6 | 10.1 | 26.2 | 10.6 |

| Separated | 23.2 | 21.9 | 26.8 | 21.1 | 0.0 | 26.7 |

| Unknown | 17.0 | 8.7 | 15.5 | 8.7 | 30.0 | 9.1 |

| Predicted annual income | ||||||

| Low (<$34,000) | 21.5 | 13.5 | 21.5 | 13.5 | 21.8 | 13.7 |

| Middle ($34,000- $67,000) | 19.6 | 11.7 | 20.2 | 12.1 | 16.0 | 9.2 |

| High ($67,000) | 15.6 | 9.4 | 16.8 | 9.4 | 6.9 | 9.4 |

| Unknown | 21.7 | 8.4 | 22.0 | 8.8 | 19.0 | 4.6 |

| Insurance type | ||||||

| Medicare | 17.1 | 9.9 | 17.3 | 10.3 | 16.1 | 7.1 |

| Commercial | 21.9 | 9.2 | 22.3 | 9.4 | 18.2 | 7.2 |

| At risk (Medicaid/ no insurance) | 22.7 | 20.7 | 23.7 | 21.2 | 18.9 | 18.7 |

| Other | 40.0 | - | 50.0 | - | 0.0 | - |

| Fractions | ||||||

| 1-20 | 11.0 | 3.6 | 10.5 | 3.5 | 14.5 | 4.8 |

| >20 | 29.4 | 18.9 | 30.8 | 19.4 | 20.5 | 44.2 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Breast | 19.5 | 6.9 | 21.1 | 6.7 | 11.3 | 7.5 |

| H&N | 29.5 | 22.8 | 31.3 | 24.4 | 22.6 | 15.9 |

| Metastasis | 11.3 | 4.3 | 9.8 | 4.1 | 20.8 | 5.9 |

| Lung | 22.8 | 12.5 | 22.2 | 12.7 | 26.7 | 11.8 |

| Prostate | 24.7 | 13.6 | 26.8 | 14.6 | 13.0 | 8.0 |

| GI | 26.8 | 15.6 | 27.9 | 15.5 | 19.0 | 16.0 |

| GYN | 20.8 | 28.4 | 20.7 | 28.7 | 22.2 | 25.0 |

| Hematologic | 12.8 | 5.1 | 13.8 | 5.9 | 7.1 | - |

| CNS | 19.4 | 3.9 | 19.8 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 33.3 |

| Other | 13.6 | 5.4 | 14.4 | 5.7 | 0.0 | - |

| Unknown | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | - | - | - |

| Distance to RT in miles | ||||||

| 0-5 | 23.9 | 14.8 | 24.0 | 15.2 | 23.5 | 12.9 |

| 5-10 | 19.2 | 13.4 | 19.5 | 13.5 | 17.4 | 12.7 |

| 10-15 | 17.2 | 10.7 | 18.6 | 11.6 | 9.1 | 4.4 |

| 15-20 | 14.3 | 12.5 | 16.3 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 21.4 |

| 20-30 | 16.7 | 8.16 | 15.8 | 9.5 | 21.4 | - |

| 30-40 | 16.2 | 5.13 | 16.9 | 5.8 | 11.1 | - |

| >40 | 20.6 | 7.2 | 20.8 | 5.9 | 19.0 | 16.0 |

| Unknown | 21.8 | 8.4 | 22.2 | 8.8 | 19.0 | 4.6 |

| RT start month | ||||||

| Nonwinter (March-October) | 17.7 | 10.3 | 18.5 | 10.5 | 13.1 | 9.0 |

| Winter (November- February) | 24.4 | 14.5 | 24.1 | 14.6 | 26.4 | 13.9 |

Abbreviations: CNS = central nervous system; GI = gastrointestinal; GYN = gynecologic; H&N = head and neck; RT = radiation therapy.

Association of population characteristics with RTI rates

Results from unadjusted and adjusted modeling of associations between risk factors and major/minor RTI rates are presented in Tables 3 and 4 , respectively. On univariate logistic regression analysis, most risk factors (eg, age <65, Black race, nonmarried status, Medicaid or no insurance coverage, prescribed treatment longer than 20 fractions, treatment in winter months [November-February], and travel distance to treatment less than or equal to 10 miles) were associated with increased major RTI risk before COVID-19. This association held during COVID-19 for Medicaid covered or patients with no insurance, nonmarried, or receiving >20 fractions. On univariate analysis, age <65, treatment longer than 20 fractions, and treatment in winter months were associated with increased minor RTI risk at baseline. During COVID-19, only treatment in winter months remained significantly associated with minor RTI.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of major (5+ RT breaks) interruptions for each treatment era

| Pre–COVID-19 era |

COVID-19 era |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| <65 | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| 65 | 0.55 (0.4-0.74) | <.01* | 0.79 (0.56-1.12) | .19 | 0.56 (0.24-1.22) | .16 | 1.06 (0.39-2.80) | .91 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| Male | 0.9 (0.68-1.19) | .46 | 0.78 (0.58-1.05) | .10 | 1.49 (0.72- 3.17) | .29 | 1.79 (0.81-4.01) | .15 |

| Race | ||||||||

| Black or African American | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| White | 0.63 (0.47-0.84) | <.01* | 0.81 (0.59-1.11) | .20 | 0.67 (0.29-1.44) | .32 | 0.62 (0.26-1.43) | .28 |

| Marital | ||||||||

| Married | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| Nonmarried | 1.53 (1.14-2.07) | <.01* | 1.33 (0.97-1.84) | .08 | 3.23 (1.30- 9.76) | .02* | 2.62 (1.02-8.10) | .06 |

| Predicted annual income | ||||||||

| Low (<$34,000) | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| Middle-high (≥$34,000) | 0.8 (0.61-1.07) | .13 | 1.13 (0.81-1.57) | .47 | 0.6 (0.28-1.25) | .17 | 0.62 (0.29-1.35) | .23 |

| Insurance type | ||||||||

| At risk (Medicaid/no insurance) | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| Commercial/Medicare | 0.39 (0.29-0.54) | <.01* | 0.44 (0.32-0.62) | <.01* | 0.33 (0.16-0.70) | <.01* | 0.38 (0.17-0.83) | .02* |

| Fractions | ||||||||

| 1-20 | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| >20 | 6.22 (4.4-9.03) | <.01* | 6.47 (4.56-9.45) | <.01* | 3.73 (1.64-9.62) | <.01* | 3.58 (1.55-9.34) | <.01* |

| RT start month | ||||||||

| Nonwinter (March- October) | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| Winter (November- February) | 1.50 (1.15-1.94) | <.01* | 1.68 (1.27-2.22) | <.01* | 1.64 (0.77-3.43) | .19 | 1.84 (0.83-4.07) | .13 |

| Distance to RT in miles | ||||||||

| 0-10 | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| >10 | 0.61 (0.47-0.80) | <.01* | 0.71 (0.53-0.93) | .02* | 0.57 (0.25-1.22) | .16 | 0.58 (0.25-1.31) | .21 |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; RT = radiation therapy.

Significant at P < .05.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of minor (2-4 RT breaks) interruptions for each treatment era

| Pre–COVID-19 era |

COVID-19 era |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| <65 | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| 65 | 0.66 (0.51-0.85) | <.01* | 0.71 (0.54-0.91) | <.01* | 0.87 (0.45-1.64) | .67 | 0.91 (0.46-1.76) | .78 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| Male | 1.04 (0.82-1.31) | .75 | 0.97 (0.76-1.25) | .84 | 1.14 (0.60-2.14) | .69 | 1.24 (0.65-2.40) | .51 |

| Race | ||||||||

| Black or African American | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| White | 0.85 (0.67-1.08) | .20 | 0.99 (0.76-1.28) | .94 | 0.57 (0.28-1.11) | .11 | 0.55 (0.27-1.09) | .09 |

| Marital | ||||||||

| Married | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| Nonmarried | 1.24 (0.97-1.58) | .08 | 1.26 (0.98-1.63) | .07 | 1.94 (0.98-4.07) | .07 | 1.90 (0.95-4.02) | .08 |

| Predicted annual income | ||||||||

| Low (<$34,000) | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| Middle-high (≥$34,000) | 0.90 (0.71-1.16) | .42 | 1.00 (0.77-1.30) | .99 | 0.62 (0.33-1.18) | .15 | 0.61 (0.32-1.17) | .13 |

| Insurance type | ||||||||

| At risk (Medicaid/no insurance) | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| Commercial/Medicare | 0.80 (0.59-1.08) | .14 | 0.94 (0.67-1.32) | .72 | 0.87 (0.44-1.78) | .69 | 0.90 (0.45-1.89) | .78 |

| Fractions | ||||||||

| 20 | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| >20 | 3.80 (2.93-4.96) | <.01* | 4.00 (3.08-5.25) | <.01* | 1.52 (0.81-2.89) | .20 | 1.46 (0.77-2.81) | .25 |

| RT start month | ||||||||

| Nonwinter (March- October) | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| Winter (November- February) | 1.40 (1.10-1.78) | <.01* | 1.66 (1.29-2.14) | <.01* | 2.38 (1.25-4.54) | <.01* | 2.35 (1.23-4.49) | <.01* |

| Distance to RT | ||||||||

| 0-10 | Reference | - | - | - | Reference | - | - | - |

| >10 | 0.86 (0.68-1.09) | .21 | 0.86 (0.68-1.09) | .22 | 0.59 (0.30-1.13) | .12 | 0.60 (0.30-1.16) | .14 |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; RT = radiation therapy.

Significant at P < .05.

On multivariate modeling, patients with Medicaid coverage or no insurance experienced higher rates of major RTI compared with patients insured commercially or through Medicare both at baseline (OR, 1/0.44 = 2.27; P < .01) and during COVID-19 (OR, 1/0.38 = 2.63; P = .02). Patients prescribed >20 fractions experienced 6.47 times higher risk (P < .01) for major RTI in the pre–COVID-19 era and 3.58 times higher risk (P < .01) during the pandemic. Treatment in winter (P < .01) and traveling <10 miles to treatment (P = .02) were associated with higher major RTI only at baseline. Age, sex, race, and predicted income were not associated with major RTI, although nonmarried status trended toward association with major RTI during COVID-19 (P = .06)

With respect to minor interruptions, age <65 (P < .01), treatment >20 fractions (P < .01), and a winter start (P < .01) were associated with higher RTI rates at baseline on multivariate analysis. Although nonmarried status (P = .08) and Black race (P = .09) trended toward associations with increased minor RTI rates during the pandemic, only winter start remained significant (P < .01).

Interaction between timing of treatment and interruption risk factors

As noted previously, interaction of treatment timing relative to COVID-19 with potential RTI risk factors was modest and was limited to minor interruptions. Specific interactions with variables are summarized for RTI rates in Tables E1 and E2. Although Medicaid/uninsured insurance status (P < .01), treatment length >20 fractions (P < .01), and winter start (P < .01) were associated with increased major RTI risk, no variable interacted significantly with treatment era. With regards to minor interruption rates, age <65 (P < .01), treatment >20 fractions (P < .01), and winter start (P < .01) were associated with higher risk for the full cohort. However, only treatment length >20 fractions interacted significantly with treatment era.

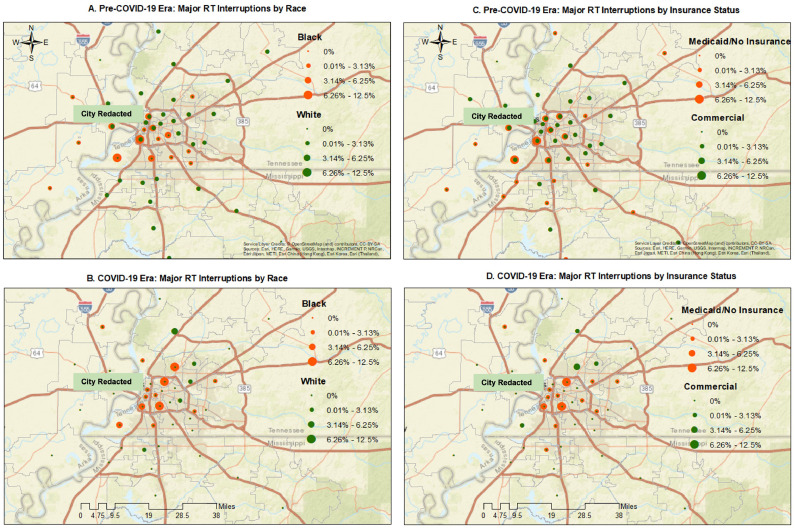

GIS analysis of RTI rates before and during COVID-19

Major RTI rates before and during the pandemic were mapped by ZIP code across the metropolitan region by race and insurance status in Fig. 2 A-D. Geographic distribution of elevated major RTI rates shifted from baseline during COVID-19 to a limited number of residential ZIP codes downtown and directly north and south of the central urban corridor, more concentrated than at baseline. Black race and Medicaid or no insurance status colocalized with highest RTI rates. ZIP codes experiencing increased RTI rates during COVID-19 overlapped or approximated ZIP codes with high SVI scores (Fig. 2E) and 2020 COVID-19 incidence rates (Fig. 2F), but these were not significant associations. The downtown location of our clinic is highlighted in these maps. LBR testing confirmed lack of association between the spatial distribution of RTI rates and baseline SVI across the full metro region (P = .11). Similarly, overlap between RTI and COVID-19 incidence rates also remained nonsignificant (P = .70). Some of the high RTI ZIP codes were in higher-income (eastern metro) regions or areas with fewer COVID-19 infections (south-central metro). Likewise, many eastern suburban ZIP codes with higher COVID-19 infection activity did not experience increased RTI rates.

Fig. 2.

(A-D) Major radiation therapy (RT) interruption rates before and during the pandemic mapped by ZIP code across the metropolitan region by race and insurance status. Geographic distribution of elevated major radiation treatment interruption (RTI) rates shifted from baseline during COVID-19 to a limited number of residential ZIP codes downtown and directly north and south of the central urban corridor, more concentrated than at baseline. Black race and Medicaid or no insurance status colocalized with highest RTI rates. (E) Geospatial location of ZIP codes with increased RTI rates during COVID-19 (outlined with bold red borders) overlayed onto ZIP codes affected by high baseline social vulnerability index (SVI), shaded in pink. Spatial distribution of RTI rates associated loosely with baseline SVI across the full metro region but did not significantly overlap quantitatively (P = .11). Department clinic location indicated with heart symbol. (F) Geospatial location of ZIP codes with increased RTI rates during the pandemic (outlined with bold yellow borders) overlayed onto ZIP code-level COVID-19 incidence rates (represented by increasing shades of red) through to December 31, 2020. Spatial distribution of RTI rates did not overlap significantly with COVID-19 incidence (P = .70). Department clinic location indicated with heart symbol.

Discussion

The effect of COVID-19 on US health care delivery and cancer treatment has been broad and deep. To our knowledge, this is the first US institutional report of longitudinal RT delivery continuity across the first year of COVID-19. Encouragingly, RTI rates during COVID-19 did not worsen, but instead trended incrementally downward. This may have resulted from either system-level resilience31 or de facto selection for patients with durable access to care. Clinical risk factors varied in their predictive associations with RTI, potentially because of limited study size, measured or unmeasured changes in cohort population, or differing mix of disease type presentations during COVID-19 (Table 1). At the cohort level, the pandemic neither exacerbated nor improved pre-existing RTI disparities; financial vulnerability and longer treatment schedules remained associated with major RTI on univariate and/or multivariate analysis (Table 3). Medicaid coverage remained a dominant predictor of high RTI rates in our study, and likely for RT access as well, consistent with high-level observations reported for ambulatory care in the US.32 Interestingly, associations were observed between a winter treatment start date and RTI risk. Potential mechanisms responsible for this finding include severe weather (ie, unseasonable heavy snowfall events) and emergence of a local SARS-CoV-2 alpha variant-driven surge between late November 2020 and January 2021. Only 1 case was documented as having treatment interrupted directly by active COVID-19 infection. No compulsory local transportation curfews were ever instituted, although voluntary “safer at home” advisories and enforcement of targeted temporary business closures and mandated remote schooling did take place.

Consistent with national19 and global33 , 34 trends, referrals to our department dropped acutely during the first months of COVID-19 (Fig. 1A). The pandemic has affected access across the full spectrum of cancer care, including screening,35 , 36 treatment,37 and even clinical trial openings.38 A dramatic example is illustrated by the decline in screening mammography in the US, which fell by up to 96% in the northeast early on.5 With recovery from the first wave, screening rates rebounded to prepandemic levels.5 , 39 This was echoed in our local patient census numbers, although on-treatment numbers never recovered as robustly as national trends. This discordant finding might be specific to patients with cancer served by an urban safety-net clinic and warrants external validation. However, it could signal future widening of cancer outcome disparities in underserved urban locations. Modeling studies and meta-analyses suggest that pandemic-associated treatment delays will lead to increased cancer mortality,40 , 41 particularly in underserved populations.42 COVID-19 infection, itself, leads to more frequent transmission and hospitalization in immunologically compromised cancer populations,43 especially in Black patients.44

We observed very modest interaction between treatment timing and RTI risk factors, limited to treatment length >20 fractions and minor RTI risk. Nonetheless, GIS mapping provided important complementary insight beyond our stable cohort-level findings, detecting discrete neighborhood-level shifts of racially defined RTI disparities (Fig. 2A-D). RTI burden in Black patients with Medicaid or no insurance became more geographically concentrated in the urban core, with only a handful of ZIP codes experiencing increased RTI rates during the pandemic. ZIP codes experiencing increases in RTI approximated but did not overlap significantly with elevated SVI measures (Fig. 2E) or COVID-19 incidence rates (Fig. 2F) across the full metro region by quantitative spatial analysis. Our finding that only a limited number of ZIP codes were affected by increased RTI rates has instructed us to view risk-directed high-resolution mapping of baseline and pandemic-related factors relevant to RTI in these most affected neighborhoods as a priority for future work.

Our central urban location positioned us to oversample from populations of patients with cancer living in racial minority, financially distressed neighborhoods. Although this may serve to improve study power to detect pandemic effect on medically underserved patients, it also limits relevance to better-resourced communities with different case mixes. Other important limitations of our analysis include the following: (1) patient selection bias and limited cohort size because of the pandemic, confining analysis to patients with the resources to make it to our clinic and start treatment; (2) potential geographic fluctuations in our catchment area toward or away from central urban areas during the pandemic because of varying system or patient-level hardships; (3) inherent difficulty distinguishing respective effect of neighborhood-level social demographics (ie, median expected household income) versus individual patient-level factors on RTI rates45 (we could only investigate patient-level social vulnerability indirectly via a proxy, ie, Medicaid coverage); (4) biases and sensitivity constraints of our mapping of community-level COVID-19 transmission (because of potential undersampling by our local testing registry, which does not include inpatient or commercial pharmacy outpatient testing) and socioeconomic vulnerability, which was quantified according to publicly available SVI data; and (5) limitations of our retrospective data collection, which precluded analysis of detailed stage distribution, interevent timing of RTI (sequential vs separated days of interruption), exact mechanistic causes for individual RTI events, and potential attrition to other treatment centers/alternative forms of disease management. The analysis of RTI rates in patients who initiated therapy at our center required an assumption that the characteristics of our COVID-19–era referral population did not change dramatically from baseline, which is suggested but not formally confirmed by findings in Table 1.

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased hardship in underserved populations facing pre-existing cancer outcome disparities.46 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others have reported disproportionate COVID-19 transmission and mortality rates in Black and Latino populations,46, 47 which have shouldered greater economic and social distress.48 Additional data and broader regional context will be required to disentangle the multifactorial effect of the pandemic and downstream public health responses on medical, financial, logistical, and social resources relevant to cancer care access. Although not directly addressed by this report, we anticipate that retrospective identification of ZIP codes with increased RTI could guide prospective confirmation and intervention strategies to mitigate obstacles to care access intensified by the crisis. Follow-up studies could include in-depth canvasing and direct outreach to these communities, supplemented by validation of individual-level predictive data to identify highest-risk patients. Use of demographic, social, and financial factors in this way may allow for automated risk-based triage of patients toward supportive resources, financial counseling, and cancer care navigation well beyond the end of the public health emergency.

For patients able to access cancer treatment, care quality has been handicapped by delayed surgeries, reduced in-person visits, and foregone adjuvant treatment.34 , 37 , 49 , 50 Fortunately, radiation oncology providers have rapidly re-established capacity through remote virtual care and in-clinic safety protocols.19 , 51 The pandemic has intensified interest52 and use33 of hypofractionated RT, such as for breast53 , 54 or prostate55 cancer, which may reduce burden and increase treatment value for patients well beyond the pandemic.56 Satisfaction may even increase for specific patient subgroups with expanded use of teleoncology via improved access and convenience.57 However, it remains important to consider that rural, older, and lower socioeconomic groups more frequently have substandard access to high-speed Internet or mobile technologies.57 , 58 Regardless of age or setting, reduced in-person health maintenance and cancer screening may result in decreased patient engagement, more advanced cancer presentations, and worsened outcome.59 Hands-on interaction, which has been so challenged by COVID-19, continues to be foundational to treatment access and quality, particularly in marginalized populations affected by trust deficits, disengagement, interrupted care, and inferior outcomes.

Conclusions

We provide the first US institutional report of RT treatment volume and interruption patterns during the first year of COVID-19. A persistent 36% overall decline in treated patient volume was observed across the first pandemic year. Although RTI rates trended incrementally downward, financially disadvantaged populations undergoing longer planned courses of RT remained more susceptible to major RTI during the pandemic. Formal GIS analysis added important insight, revealing discrete geographic shifts in interruption risk to marginalized racial minority patients living in urban downtown neighborhoods. Such findings could be leveraged to design focused RT access enhancement strategies tailored to specific community locations well beyond the pandemic, but this will require replication to validate and broaden relevance.

Footnotes

This project was presented in part in poster format at the 2021 AACR Virtual Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorites and the Medically Underserved.

This work was supported by a UTHSC-University of Memphis SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 Research CORNET Award to D.L.S. and a UTHSC Medical Student Summer Cancer Research Award to E.G.

Disclosures: M.P. was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U24AT011310-02, R01MD013858-03, and P01CA229997-04 outside the scope of this work. D.L.S. was supported by National Institutes of Health grant U24AT011310-02 outside the scope of this work.

Data sharing statement: Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2022.09.073.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Ferrer RA, Acevedo AM, Agurs-Collins TD. COVID-19 and social distancing efforts-implications for cancer control. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:503–504. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jazieh AR, Akbulut H, Curigliano G, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care: A global collaborative study. JCO Global Oncol. 2020;6 doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00351. 1428-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Niles J, et al. Changes in the number of us patients with newly identified cancer before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patt D, Gordan L, Diaz M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on cancer care: How the pandemic is delaying cancer diagnosis and treatment for American seniors. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:1059–1071. doi: 10.1200/CCI.20.00134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeGroff A, Miller J, Sharma K, et al. COVID-19 impact on screening test volume through the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program, January-June 2020, in the United States. Prev Med. 2021;151 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai AG, Pasea L, Banerjee A, et al. Estimated impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer services and excess 1-year mortality in people with cancer and multimorbidity: Near real-time data on cancer care, cancer deaths and a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakefield DV, Carnell M, Dove APH, et al. Location as destiny: Identifying geospatial disparities in radiation treatment interruption by neighborhood, race, and insurance. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;107:815–826. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bese NS, Hendry J, Jeremic B. Effects of prolongation of overall treatment time due to unplanned interruptions during radiotherapy of different tumor sites and practical methods for compensation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giddings A. Treatment interruptions in radiation therapy for head-and-neck cancer: Rates and causes. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2010;41:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuo K, Machida H, Ragab OM, et al. Patient compliance for postoperative radiotherapy and survival outcome of women with stage I endometrioid endometrial cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:482–491. doi: 10.1002/jso.24690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urjeet A, Patel MOP, Holloway N, Rosen F. Poor radiotherapy compliance predicts persistent regional disease in advanced head/neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2009;119 doi: 10.1002/lary.20072. 538-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petereit DG, Sarkaria JN, Chappell R, et al. The adverse effect of treatment prolongation in cervical carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32:1301–1307. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00635-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leticia M, Nogueira LS, Efstathiou JA. Association between declared hurricane disasters and survival of patients with lung cancer undergoing radiation treatment. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;322:269–271. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.7657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khalil AA, Bentzen SM, Bernier J, et al. Compliance to the prescribed dose and overall treatment time in five randomized clinical trials of altered fractionation in radiotherapy for head-and-neck carcinomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:568–575. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03790-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohri N, Rapkin BD, Guha C, et al. Radiation therapy noncompliance and clinical outcomes in an urban academic cancer center. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;95:563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox JD, Pajak TF, Asbell S, et al. Interruptions of high-dose radiation therapy decrease long-term survival of favorable patients with unresectable non-small cell carcinoma of the lung: Analysis of 1244 cases from 3 radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27:493–498. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas K, Martin T, Gao A, et al. Interruptions of head and neck radiotherapy across insured and indigent patient populations. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e319–e328. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.017863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen J, Almukhtar S, Aufrichtig A, et al., Coronavirus in the U.S.: Latest map and case count. The New York Times, 2022. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/covid-cases.html. Accessed April 14, 2022.

- 19.Wakefield DV, Sanders T, Wilson E, et al. Initial impact and operational responses to the COVID-19 pandemic by American radiation oncology practices. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108:356–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S, Heo J. Covid-19 pandemic: A new cause of unplanned interruption of radiotherapy in breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2021;39:5. doi: 10.1007/s12032-021-01604-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ying X, Bi J, Ding Y, et al. Management and outcomes of patients with radiotherapy interruption during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.754838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alterio D, Volpe S, Marvaso G, et al. Head and neck cancer radiotherapy amid COVID-19 pandemic: Report from Milan, Italy. Head Neck. 2020;42:1482–1490. doi: 10.1002/hed.26319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tramacere F, Asabella AN, Portaluri M, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on radiotherapy supply. Radiol Res Pract. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/5550536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venkatasai J, John C, Kondavetti SS, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patterns of care and outcome of head and neck cancer: Real-world experience from a tertiary care cancer center in India. JCO Glob Oncol. 2022;8 doi: 10.1200/GO.21.00339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthews P. Mathews Malnar and Bailey; Fairport Harbor, OH: 2010. Sample Size Calculations: Practical Methods for Engineers and Scientists — Tests for the Difference Between Two Poisson Rates. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index. Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html. Accessed February 10, 2022.

- 27.PolicyMap. PolicyMap database. Available at: https://www.policymap.com. Accessed February 10, 2022.

- 28.Hibbert JD, Liese AD, Lawson A, et al. Evaluating geographic imputation approaches for ZIP code level data: An application to a study of pediatric diabetes. Int J Health Geogr. 2009;8:54. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-8-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo D. Local entropy map: A nonparametric approach to detecting spatially varying multivariate relationships. Int J Geogr Inform Sci. 2010;24:1367–1389. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esri. ArcGIS Pro.30. Available at: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/proapp/2.8/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/localbivariaterelationships.htm. Accessed February 10, 2022.

- 31.Decker KM, Lambert P, Feely A, et al. Evaluating the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on New Cancer Diagnoses and Oncology Care in Manitoba. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:3081–3090. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28040269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mafi JN, Craff M, Vangala S, et al. Trends in us ambulatory care patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2019-2021. JAMA. 2022;327:237–247. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spencer K, Jones CM, Girdler R, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on radiotherapy services in England, UK: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:309–320. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30743-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riera R, Bagattini AM, Pacheco RL, et al. Delays and disruptions in cancer health care due to COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic review. JCO Glob Oncol. 2021;7:311–323. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papautsky EL, Hamlish T. Patient-reported treatment delays in breast cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;184:249–254. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05828-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, et al. Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:878–884. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eskander A, Li Q, Hallet J, et al. Access to cancer surgery in a universal health care system during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamont EB, Diamond SS, Katriel RG, et al. Trends in oncology clinical trials launched before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McBain RK, Cantor JH, Jena AB, et al. Decline and rebound in routine cancer screening rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:1829–1831. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06660-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: A national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, et al. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;371:m4087. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balogun OD, Bea VJ, Phillips E. Disparities in cancer outcomes due to COVID-19: A tale of 2 cities. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1531–1532. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Q, Berger NA, Xu R. Analyses of risk, racial disparity, and outcomes among us patients with cancer and COVID-19 infection. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:220–227. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fu J, Reid SA, French B, et al. Racial disparities in COVID-19 outcomes among black and white patients with cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng E, Soulos PR, Irwin ML, et al. Neighborhood and individual socioeconomic disadvantage and survival among patients with nonmetastatic common cancers. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.39593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kantamneni N. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on marginalized populations in the United States: A research agenda. J Vocat Behav. 2020;119 doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Curiskis A, Glickhouse R, Goldfarb A, et al., The COVID Tracking Project, The Atlantic: The Atlantic Monthly Group, 2021. Available at: https://covidtracking.com. Accessed March 7, 2021.

- 48.M Barry, IX Kendi, R Lee, et al., The COVID Racial Data Tracker. The Atlantic: The Atlantic Monthly Group, 2021. Available at: https://covidtracking.com/race. Accessed March 7, 2021.

- 49.Sharpless N. Q&A: Ned Sharpless on COVID-19 and cancer prevention. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2021;14:615–618. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-21-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Decker KM, Lambert P, Feely A, et al. Evaluating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on new cancer diagnoses and oncology care in Manitoba. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:3081–3090. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28040269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wakefield DV, Eichler T, Wilson E, et al. Variable impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. radiation oncology practices. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;113:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2022.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Portaluri M, Barba MC, Musio D, et al. Hypofractionation in COVID-19 radiotherapy: A mix of evidence based medicine and of opportunities. Radiother Oncol. 2020;150:191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta A, Ohri N, Haffty BG. Hypofractionated radiation treatment in the management of breast cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:793–803. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2018.1489245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray Brunt A, Haviland JS, Wheatley DA, et al. Hypofractionated breast radiotherapy for 1 week versus 3 weeks (FAST-Forward): 5-year efficacy and late normal tissue effects results from a multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1613–1626. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30932-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roy S, Morgan SC. Hypofractionated radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: When and for whom? Curr Urol Rep. 2019;20:53. doi: 10.1007/s11934-019-0918-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Konski AA. Defining value in radiation oncology: Approaches to weighing benefits vs costs. Oncology (Williston Park) 2017;31:248–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shaverdian N, Gillespie EF, Cha E, et al. Impact of telemedicine on patient satisfaction and perceptions of care quality in radiation oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:1174–1180. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Franco I, Perni S, Wiley S, et al. Equity in radiation oncology post-COVID: Bridging the telemedicine gap. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108:479–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jazieh AR, Chan SL, Curigliano G, et al. Delivering cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Recommendations and lessons learned from ASCO global webinars. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1461–1471. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.