Graphical abstract

Keywords: COVID-19 disease, Synoptic atmospheric circulation, Air quality, Seasonal variability of climate and Planetary Boundary Layer height, NOAA satellite data

Abstract

Like several countries, Spain experienced a multi wave pattern of COVID-19 pandemic over more than one year period, between spring 2020 and spring 2021. The transmission of SARS-CoV-2 pandemics is a multi-factorial process involving among other factors outdoor environmental variables and viral inactivation.This study aims to quantify the impact of climate and air pollution factors seasonality on incidence and severity of COVID-19 disease waves in Madrid metropolitan region in Spain. We employed descriptive statistics and Spearman rank correlation tests for analysis of daily in-situ and geospatial time-series of air quality and climate data to investigate the associations with COVID-19 incidence and lethality in Madrid under different synoptic meteorological patterns. During the analyzed period (1 January 2020-28 February 2021), with one month before each of three COVID-19 waves were recorded anomalous anticyclonic circulations in the mid-troposphere, with positive anomalies of geopotential heights at 500 mb and favorable stability conditions for SARS-CoV-2 fast diffusion. In addition, the results reveal that air temperature, Planetary Boundary Layer height, ground level ozone have a significant negative relationship with daily new COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths. The findings of this study provide useful information to the public health authorities and policymakers for optimizing interventions during pandemics.

1. Introduction

The worse pandemic in the last century caused by novel RNA coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and its variants, causative agent of COVID-19 disease, first time identified in the Wuhan area, China, in December 2019 and then transmitted, e.g., to Northern Italy and Spain in early 2020 is responsible for a global crisis spreading the disease and collapsing the world economy. The infectious degree of this pandemic is very high and, therefore, the consequences of the transmission have been very hard for the entire World (Yuki et al., 2020). Recently, more new transmissible variants of SARS-CoV-2 have been identified globally (WHO, 2021a). The virus has infected globally almost 174,443,743 people and it has caused almost 3,753,998 deaths up to 8 June 2021, being reported in approximately 222 countries and territories. On 3 March 2020, the first case of COVID-19 death was registered in Madrid, and by 8 June 2021 have been recorded 3,707,523 confirmed cases and 80,236 deaths in Spain. More than 18.93 % percent of COVID-19 positive cases occurred in the region of Madrid, and Madrid accounted for around 35.55 % percent of the total number of fatalities recorded in Spain. Madrid metropolitan region and one of the main foci of the COVID-19 in Europe (CM, 2021 ).

Since the first emergence of viral infection in February 2020 till the end of February 2021, and the emergence of multiple variants of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, Spain has experienced three successive waves of COVID-19 pandemic. If the first COVID-19 wave (15 February to 15 June 2020) was a hard outbreak related to community transmission, insufficient information and sanitary treatments, the second COVID-19 wave (10 August– 30 November 2020) started with increasing social activities and tourism due to so called “new normality” by June 21, 2020, with poor social distancing, being better mitigated by the rapid reinforcement of sanitary measures during the early stages. Compared to the second wave, the third COVID-19 wave (1 December 2020– 28 February 2021) was characterized by delayed social distancing reinforcement, winter holidays, longer duration and higher viral infections and fatalities rates. The ongoing fourth coronavirus wave that started on 1 March 2021 is of smaller intensity than the third wave.

In order to minimise global COVID-19 disease spread, forecast its rate of circulation and develop proper therapies and vaccines, intense multidisciplinary international scientific efforts try to find the linkage between the spatiotemporal variability of environmental factors responsible of the fast diffusion, and infectivity of the SARS-CoV-2 and its new variants virions (Amin et al., 2020; Hassanzadeh et al., 2020; Coccia, 2020a, b).

Several scientific studies suggest that increased air pollutant concentrations in big cities (particulate matter PM2.5 and PM10, O3 and NO2) including Saharan dust intrusions in Southern Europe, and Spain contribute to the worsening of multiple pathologies associated with human cardiorespiratory and immune systems (Frontera et al., 2020; Salvador et al., 2019; Zoran et al., 2020a). It is considered that the changes in the levels of urban air pollution are determined by several factors, including natural and anthropogenic sources and the rates of emissions, local and regional atmospheric circulation patterns, the physicochemical composition of the atmosphere, meteorological variables, and ventilation conditions of the atmospheric space of the metropolitan region, as well as spatiotemporal variability of meso- and microclimatic parameters (Zhou et al., 2018; Molepo et al., 2019; Pfahl et al., 2015; Baldasano, 2020; Bashir et al., 2020a; Zoran et al., 2008; Zoran et al., 2013). Air pollution episodes characterized by a high level of air pollution over an urbanized area for several days (Pandolfi et al., 2014) can be correlated not only with local conditions but also with trans-border air pollution contribution as is the case of Saharan dust intrusions (Linares et al., 2021) for Madrid metropolitan region. Due to oxidative potential of urban air pollutants, several epidemiological and toxicological studies demonstrated their adverse effects on air airway inflammatory and cardiovascular diseases (Domingo, Rovira, 2020; Sugiyama et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Seposo et al., 2020; Kelly, Fussell, 2011; Tager, 2005; Zoran et al., 2020b). It seems that during stagnant air conditions is a strong correlation between short-term or long-term exposure and specific characteristics of ecotoxicity, genotoxicity, and oxidative potential of particulate matter PM2.5 and PM10 and gaseous pollutants ozone (O3) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and an increased susceptibility to morbidity and mortality from respiratory infections (Iqbal et al., 2021; Romano et al., 2020; Cohen and Kupferschmidt, 2020; Perrone et al., 2012, 2014; Wang et al., 2018a,b; Wang et al., 2020a,b,c; Li et al., 2004). At the near-surface atmosphere, particulate matter can attach viral, bacterial, and fungal bioaerosols, which can target the human immune system through damage of innate immune recognition receptors that respond to unique pathogen-associated molecular patterns (Bowers et al., 2009, 2013; Bosch et al., 2003; Cao et al., 2014, 2020; Jones and Harrison, 2004; Khan et al., 2019; Kawasaki et al., 2019; Mousavizadeh, Ghasemi, 2020). Regarding seasonality of SARS-CoV-2, the genetic drift is currently unknown, and according to previous viral infections pandemic known as SARS and MERS-CoV, new waves infections are likely to occur, with unpredictable height and breadth of the waves (Baay et al., 2020; Moriyama et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2020; Rayan, 2021).

Assessing the impact of environmental and social factors of large cities/metropolitan regions to the exposure of viral infectious diseases is an important issue for preventing/protection and future decision making policies of new COVID-19 outbreaks and the transmission of other viral agents in terms of people’s health (Bashir et al., 2020a,b; Moryama et al., 2020; Haque and Rahman, 2020).

Ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic over several seasons confirms the important role of the climate and environmental factors in SARS-CoV-2 and its new variants airborne diffusion route, from a reservoir to a susceptible host in densely populated urban areas.

In this study, we focus on the analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 viral infection fast diffusion relation with environmental variables that could affect droplet and bioaerosols transmission and viral survival. Also, this study examines how different synoptic atmospheric circulation patterns, that influenced turbulent processes and wind circulations at regional and local scales, may be related to the three COVID-19 waves start-up and evolution in the Madrid metropolitan region. Based on daily in-situ and geospatial time series data statistical analysis and Spearman rank correlation tests, this study aims to compare air pollution and climate factors, which can trigger the spread of SARS-CoV-2 viral infection during the first, second and third COVID-19 pandemic waves. The specific goal of this study is to explore the relation between the change in weather-related factors and the COVID-19 incidence and severity in Madrid region during several seasons and over one year pandemic time period 1 January 2020-28 February 2021. In addition, this study examines how different synoptic atmospheric circulation patterns, that influenced turbulent processes and wind circulations at regional and local scales, may be related to the three COVID-19 waves start-up and evolution in the Madrid metropolitan region. Accurate estimation of the local and regional seasonality of the environmental and epidemiological conditions can provide vital information on the characteristics of the effects of the COVID-19 disease impact on the future pandemic waves.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Novel coronavirus COVID-19 disease

Presently it has been more than one year since the first cases of the new coronavirus variant SARS CoV-2 that invades host cells using an endocytic pathway have been detected in Wuhan, Hubei province in China. This coronavirus is a new enveloped virus positive-sense, single-stranded RNA with roughly spherical or moderately pleomorphic virions of approximately 60–140 nm with an average to 0.1 μm in diameter (Mousavizadeh and Ghasemi, 2020; Lu et al., 2020; Shang et al., 2020; Bosch et al., 2003; Rivellese, Prediletto, 2020). The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (S) with two subunits on the surface of the virus is a key factor involved in viral infection, playing an essential role in the receptor recognition and cell membrane fusion process of the virus particle to the host cell through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (Liu et al., 2020a,b; Walls et al., 2020). Changes in the spike protein can result in different variants (Liu et al., 2020a,b; Wrapp et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). Its genetic and structural similarities to previous coronaviruses SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV in 2003 and respectively in 2012 explain the aggressive inflammatory response of severe pneumococcal disease (Zowalaty, Järhult, 2020). The SARS-CoV-2 genome has the capability of suffering rapid mutations as the virus spreads (Luo et al., 2020a; Mu et al., 2020; Grubaugh et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020a,b,c; Bishop et al., 2004; Shang et al., 2020).

The most worrying emerging coronavirus variants which cause major changes in the way the pathogen acts, including alterations to its contagiousness have been developed in rapid succession in different geographical regions, such as Spain (20A.EU1- identified in late summer 2020 contains a mutation called A222 V on the viral spike protein), the U.K. (VOC 202012/01- with notable mutation: N501Y was first identified in December 2020), South Africa (501Y.V2- with notable mutations E484 K, N501Y, and K417 N was first detected in South Africa in December 2020) and Brazil two variants (more aggressive P.1 – with notable mutations E484 K, K417 N/T, N501Y identified at the middle of 2020 in Brazil. Presently, Delta (B.1.617.2) and its new variant delta plus, first detected in India have - high transmission COVID-19 disease rates among humans, - being of great health concern -in Europe and worldwide (Bakhshandeh et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020a,b,c). Besides Spanish variant of SARS-CoV-2, in Spain have been identified mostly UK and Brazil variants. Spain has known the severity of this first phase of COVID-19 in terms of cases and deaths. The second and the third waves were also hard tests for Spanish society, due to existence of socioeconomic differentials in COVID-19 disease exposure, and existing social inequalities (Glodeanu et al., 2021).

2.2. Urban air pollution related to COVID-19 spread

Several epidemiologic studies linked exposure to ambient air pollution with particulate matter and gaseous pollutants and occurrence of numerous respiratory viral infectious diseases transmission during several seasons (Wilson, Suh, 1997; Baklanov et al., 2016; Qian et al., 2010). Was shown that worse air quality was associated with increase SARS fatality (Cui et al., 2003) and increase influenza incidence during winter seasons (Landguth et al., 2020). Under laboratory conditions, was demonstrated a long time viability of SARS-CoV-2 in ambient aerosols, as an important source of COVID-19 transmission (van Doremalen et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020b; Li et al., 2020a,b). Airborne microbial (bacterial, fungal, viral) communities and their seasonal shift in both the concentration and biodiversity have been systematically observed in the Planetary Boundary Layer(PBL) (Tignat-Perrier et al., 2020; Zoran et al., 2020b; Lepeule et al., 2014; Artínano et al., 2003) and especially in urban areas (Mhuireach et al., 2019). The seasonal variability was associated to changes in surface air conditions at landscape interactions, (Bowers et al., 2013), meteorological conditions (Uetake et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020a, Liu et al., 2020b) and/or changes in the global air circulation (Cáliz et al., 2018). Currently, the pathogenesis of COVID-19 deadly epidemics is not yet very clear (Nishiura et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020a,b; Walls et al., 2020), but its existence as viral bioaerosol indoors and outdoors explains its pathogenicity, acting on the human immune system through damage of innate immune recognition receptors that respond to unique pathogen-associated molecular patterns (Jones and Harrison, 2004). Bioaerosols are present in most of the enclosed environments due to its ubiquitous nature, but can be found and outdoor (Ariya, Amyot, 2004; Gong et al., 2020; Minhaz Ud-Dean, 2010; Wang et al., 2020a,b,c). Saharan dust storms can spread different microbiota that survive long-range transport in the atmosphere (Chuvochina et al., 2011; Linares et al., 2017). On 5 October 2020 World Health Organization recognized that airborne transmission can be a possible route of SARS-CoV-2 viral infection diffusion by respiratory droplets (larger and smaller) and particles that can remain suspended in air and travel far from the source on air currents (WHO, 2020; WHO, 2021b).

Presently, is considered that the main routes of COVID-19 transmission in humans are:

-

1)

inhalation of respiratory droplets sprays (sneeze or cough)- aerosol of virus-laden respiratory tract fluid, typically greater than 5 μm in diameter (Vejerano, Marr, 2018; Harrison et al., 2005),

aerosol transmission can allow the coronavirus to deeply penetrate into the lower respiratory tract of humans and cause severe symptoms (Karimzadeh et al., 2021);

-

2)

close contact with infected persons;

-

3)

contact with surfaces contaminated with SARS-CoV-2;

-

4)

a possible oral/fecal transmission through wastewater and sewage sludge produced by hospitals and houses with infected people (Collivignarelli et al., 2020; Carraturo et al., 2020; Wurtzer et al., 2020).

In confined spaces, like hospitals were found two distinct size ranges of bioaerosols with SARS-CoV-2 pathogens, with aerodynamic diameter dominant between 0.25–1.0 μm, and with a diameter larger than 2.5 μm (Liu et al., 2020a,b; Li et al., 2020a,b). Viral infectivity due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is defined as the capacity of coronavirus to attach and enter the host cell using its resources to produce new virions. Knowing this parameter is of fundamental importance for future prevention and control strategies, that require an improved understanding of SARS-CoV-2 dynamics of current and future COVID-19 waves. Viral load is one of the main variable of viral kinetics in pandemic infectious disease transmission (Cevik et al., 2021).

Aerosolised COVID-19 viral infection disease difussion can be done by droplet or airborne transmission, function of their size, the site of generation (Gralton et al., 2011), the modes of transmission and environmental variables both indoors and outdoors. Droplet transmission considered the main source of viral diseases, defined as the transmission of viral infection by droplets with diameter size ≤ 5 μm via direct or indirect physical contact with recipients, is different of airborne transmission, which means inhalation of small droplets attached to particulate matter or droplet nuclei containing SARS-CoV-2 virions with diameter size > 5 μm (Ram et al., 2021; Vejarano, Marr, 2018). It seems that physicochemical reactivity of PM microparticles and nanoparticles is an essential factor for the SARS-CoV-2 virions attachment, the number, size distribution, and virion loading of atmospheric particulate matters being of great relevance for the development and severity of the COVID-19 disease (Duval et al., 2021).

Besides the recognized role as coronavirus carriers of particulate matter in different size fractions (PM0.1 μm, PM2.5 μm and PM10 μm), it seems that is a strong correlation between short-term or long-term exposure and specific characteristics of toxicity of ground levels of particulate matter and gaseous pollutants ozone (O3), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), carbon monoxide (CO), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), polyciclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), etc. frequently occured at high concentration values in densely populated metropolitan areas in Europe, like Madrid is in Spain (Penache and Zoran, 2019a, Penache and Zoran, 2019b; Li et al., 2020a, Li et al., 2020b; Wu et al., 2020; Zoran et al., 2019). Through induced oxidative stress, responsible of the free radicals production, damaging of the cardio-respiratory and immune systems, and altering the host resistance to viral and bacterial infections, urban air pollutants can increase susceptibility to mortality and morbidity from respiratory infections (Ciencewicki and Jaspers, 2007; Martelletti, Martelletti, 2020; Alghamdi et al., 2014; Asadi et al., 2020; Carugno et al., 2016; Romano et al., 2020; Cohen and Kupferschmidt, 2020). Recent advances in studies of mechanisms associated with airway disease attributed to air pollutants considered epigenetic alteration of genes by combustion-related pollutants and how polymorphisms in genes involved in antioxidant pathways and airway inflammation can modify responses to air pollution exposures (Kelly and Fussell, 2011; Xie et al., 2018), and generate new viral mutations through involving the non-structural proteins or structural proteins such as S protein, which can favor the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic (Bakadia et al., 2021).

2.3. Local and regional climate factors impact on COVID-19 transmission

It is known that coronaviruses display various diffusion patterns among humans, anyway their transmissibility is influenced by the geographic location, season, and the local and regional climate conditions (wind speed intensity and direction, air relative humidity, air temperature and pressure, precipitation, Planetary Boundary Planetary Boundary Layer, and synoptic atmospheric circulation patterns) in which pathogen and host meet both outdoor as well as indoors (Poole, 2020; Conticini et al., 2020; Collivignarelli et al., 2020; Nuvolone et al., 2018). The weather conditions in big cities like as atmospheric thermal inversions, fog or haze, extreme climate events (like as thunderstorms, strong winds, heat and cold waves, urban heat island phenomenon, etc) can have a high impact on local, regional and trans-border air pollutants and bioaerosols (viruses, bacteria and fungi) transport.

Recent multiple studies focused on the analysis of the different meteorological factors impacts on the first COVID-19 wave incidence and severity in different worldwide regions, considering air pollution and geographic factors and seasonal variability of local and regional climate features (Denes et al., 2020; Tobias and Querol, 2020; Sajadi et al., 2020a,b; Zhao et al., 2021; Bontempi, 2020).

Viral human infections associated with SARS-CoV, influenza virus, rhinovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus have been directly related to climate variables like as ambient air temperature, relative air humidity, wind speed intensity, atmospheric pressure, precipitation rate (Coccia, 2021a; Ciencewicki and Jaspers, 2007; Domingo et al., 2020; Barreca, 2012; Domingo, Rovira, 2020; Carugno et al., 2018; Coccia, 2020a, c; Ballabio et al., 2013; Bashir et al., 2020a,b). Both indoors (Jin, 2020) and outdoors, the air is contaminated by particulate matter, gases, bacteria, fungi and viruses. Outdoor specific climate conditions can be top predictors of airborne coronavirus illnesses diffusion (Poole, 2020; Setti et al., 2020a, b). Was recognized that besides human behavior, environmental parameters are the main two major contributing factors for the seasonal nature of respiratory viral infections with a high impact on respiratory SARS-CoV-2 virus stability and transmission rates (Moriyama et al., 2020).

Several studies revealed that urban air pollution depends on local or regional emission sources, photochemical reactions, and meteorological variables, including the thermodynamic structure of the Planetary Boundary Layer(PBL), which determines the vertical atmospheric mixing of air pollutants. While in a cyclonic convective boundary layer, air quality is influenced by the dispersion/transport processes of air pollutants due to wind shears and convective turbulence, in an anticyclonic stable boundary layer, with potential temperature inversions, vertical mixing is weak, which leads to the accumulation of air pollutants (Miao and Liu, 2019; Tang et al., 2016a,b; Li et al., 2017; Yadav et al., 2016). So, diurnal variation pattern of the PBL thermodynamic structure can affect surface concentrations of particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) and gaseous air pollutants (e.g. O3, NO2, CO2, SO2).

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Investigation test site

Madrid Community region, located in the centre of the Iberian Peninsula in Spain (Fig. 1 ), with Madrid city (40.40792 °N, 3.69281 °W) and 26 satellite towns is one of Europe’s region the most affected by COVID-19 pandemic waves. Total area of Community of Madrid region is of 8,030.1 km2, of which Madrid capital has an area of 604.3 km². It has a population of 6.661million inhabitants, and a density of 829.62 inhabitants/km2, representing 14.2 % of Spain population. Madrid's economy, based on industry, service, construction and transport sectors brings high levels of air pollution (Gómez-Losada et al., 2019). Madrid city is recognized by extreme climate events like as summer heat waves under Urban Heat Island (UHI), and trans-border Saharan intrusions over the spring-summer periods, (Salvador et al., 2004, 2012; Salvador et al., 2021; Díaz et al., 2006, Díaz et al., 2015, Díaz et al., 2017, Díaz et al., 2019; Linares et al., 2020). Road traffic-related air pollution (Cuevas et al., 2014; Monzón and Guerrero, 2004) is the main source of O3 precursors in the basin, representing 65 % of NOx, 67 % of CO, 87 % of PM10 and 85 % of PM2.5 and 14 % of total VOCs emissions per year, respectively (Salvador et al., 2004; Salvador et al., 2012; Montero and Fernández-Avilés, 2018; Valverde et al., 2016). Although during the last years NO2 and PM10 ambient air concentrations have shown a clear decreasing trend due to the emission reductions in the road traffic, Madrid metropolitan area has experienced an increase of 30–40 % of ambient air O3 levels (Saiz-López et al., 2017). Air pollution still presents exceedances of air quality legal limits according to the Directive 2008/50/EC.

Fig. 1.

Investigated test site Madrid metropolitan region in Spain.

3.2. Data used

-

•

COVID-19 data

Almost real time data for coronavirus COVID-19 incidence Total, Daily New, Daily New Deaths and Total Deaths cases recorded in Spain and Madrid have been provided by the following websites: https://www.worldometers.info and https://www.statista.com/, being provided by the National Center for Epidemiology at the Carlos III Health Institute. Accumulated COVID-19 data for 15 February 2020- 28 February 2021 time period for Madrid metropolitan region were provided by https://www.comunidad.madrid/servicios/salud/coronavirus.

-

•

Air pollution and climate data

Time series data of daily average air pollutants concentrations PM2.5, PM10, O3 and NO2 for Madrid selected stations have been collected from https://aqicn.org/ and from http://www.mambiente.madrid.es/sica/scripts/index.php. Time series of meteorological data, including daily average temperature (T), daily average relative humidity (RH), and daily average wind speed for Madrid were retrieved from the State Meteorological Agency (Agencia Estatal de Meteorología- AEMET), Weather Wunderground (https://www.wunderground.com/), and Copernicus climate data (climate.copernicus.eu). Planetary Boundary Layer height (PBL) data were collected from the archived data of NOAA’s Air Resources Laboratory (https://ready.arl.noaa.gov). In order to describe urban air quality of Madrid metropolitan area, in Spain this paper considered Global Air Quality Index (AQI) according to classification of air quality (http://www.eurad.uni-koeln.de) and EU regulations, which is defined by formula:

| (1) |

where , , , , represent daily mean values of respectively O3, PM10, NO2, sulphur dioxide and carbon monoxide present in the urban air. Based on the global criteria for main air pollutants (O3, PM10, NO2, SO2, CO) air quality is classified in six classes from very good to very poor (respectively: < 10-very good; 10 – 20- good; 20 – 30- satisfactory; 30–50 – sufficiently; 50 – 80- poor; > 80- very poor).

-

•

Reanalysis satellite data

The daily 500 hPa geopotential anomaly height charts for Europe and Spain have been provided by NASA, Reanalysis Data Project NCEP/NCAR PSD, Boulder, Colorado, USA (http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/). In order to analyze Madrid lower atmospheric circulation conditions associated with people’s exposure to air pollutants and COVID-19 transmission during 1 January 2020 - 28 February 2021, we extracted the daily anomalies of 500 hPa geopotential height at about 5.5 Km altitude above the ground at Spain and Europe scales, where positive anomalies are associated with the anticyclones stability conditions like as, blocking systems, and negative anomalies with cyclones conditions.

-

•

Descriptive statistical analysis

We performed descriptive analysis and compared air pollution and climate data (considered independent variables) with COVID-19 incidence data (considered dependent variables) between first, second and third waves. All data analyses have been processed in ORIGN 10.0 software. First, a descriptive analysis was performed to provide an overview of COVID-19 incidence and air quality during the study period. Next, for time series of data we used a linear regression model to fit the dependent variables (COVID-19 incidence) for each independent variable: ambient air pollutants (particulate matter PM2.5, PM10, ozone O3 and NO2) and meteorological parameters (daily average air temperature-, air relative humidity- RH, wind speed intensity –w and daily maximum Planetary Boundary Layer height - PBL). The dependence between pairs of time series was quantified in this study by standard tools of statistical analysis, Spearman and rank-correlation non-parametric test coefficients. The main reason for using non-parametric statistical tests is that compared with parametric statistical tests, are thought to be more suitable for non- normally distributed data, which are frequently involved in time series air pollution and climate variables. In order to use no-parametric rank correlation Spearman tests, were applied the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Tests of Normality for time-series data sets, that provided very good evidence that the considered time-series data were not normally distributed. The values for levels of correlation are bound in the range [0, +1], with 0 for no association and +1 for complete positive association and [0, -1] with −1 as negative correlation. Another parameter „p-value” tells us if the result of an experiment is statistically significant. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Though correlation and p-value provides us with the relationship between variables, care should be taken to interpret them correctly.

4. Results

4.1. Air pollutants impact on COVID-19 waves

Regarding the air pollutants emission sources of Madrid, industry and traffic related are the predominant emission sources of primary pollutants, PM2.5 and fossil-fuel combustion by-products, like as NO2, which are especially prevalent with a significant threat to human health (Borge et al., 2019; Linares et al., 2018). Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics that correspond to the mean of daily average concentrations of PM2.5, PM10, O3, and NO2 together with mean of daily average air quality index and standard deviations for Madrid region during the five time periods (COVID-19 pre-lockdown from 1 January –15 February 2020; COVID-19 beyond lockdown during first wave-15 February -15 June 2020; COVID-19 under heat wave-15 June- 10 August 2020; COVID-19 under second wave- 10 August – 30 November 2020; and COVID-19 under third wave-1 December 2020-28 February 2021).

Table 1.

Main air pollutants concentrations and air quality index for Madrid region during the five time periods (COVID-19 pre-lockdown, COVID-19 beyond lockdown during first wave, COVID-19 under heat wave, COVID-19 under second wave, and COVID-19 under third wave).

| Time period | 1 January –15 February 2020-pre-lockdown | 15 February -15 June 2020 during the 1-st COVID-19 wave and beyond lockdown | 15 June- 10 August 2020 under heat wave | 10 August – 30 November 2020, during the 2-nd COVID-19 wave | 1 December 2020-28 February 2021, during the 3-rd COVID-19 wave | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily average | Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | Range |

| PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 28.64 ± 12.24 | 10-52 | 20.43 ± 10.57 | 8-65 | 28.15 ± 9.87 | 8-50 | 23.06 ± 8.29 | 9-57 | 21.92 ± 15.31 | 6-72 |

| PM10 (μg/m3) | 71.44 ± 23.44 | 32-126 | 51.70 ± 17.28 | 23-109 | 64.11 ± 15.09 | 33-96 | 54.64 ± 15.06 | 23-90 | 52.08 ± 29.00 | 15-147 |

| O3 (μg/m3) | 15.54 ± 7.56 | 1-30 | 31.89 ± 7.03 | 13-51 | 46.25 ± 13.17 | 23-109 | 29.53 ± 11.71 | 7-64 | 22.41 ± 6.98 | 2-33 |

| NO2 (μg/m3) | 28.07 ± 10.03 | 14-62 | 13.07 ± 8.62 | 2-43 | 15.92 ± 6.36 | 6-42 | 21.32 ± 8.48 | 4-40 | 22.22 ± 13.44 | 5-72 |

| AQI | 30.39 ± 10.48 | 16-62 | 30.56 ± 6-59 | 16-50 | 34.02 ± 5.06 | 22-50 | 27.25 ± 7.02 | 12-50 | 25.89 ± 8.03 | 13-62 |

As can be seen in Table 1, the comparative analysis of the daily mean values and standard deviations of particulate matter PM2.5, PM10 concentrations and AQI between the three COVID-19 waves periods together heat wave period in comparison with pre-lockdown period highlights that during COVID-19 pandemic waves, both particulate matter PM2.5 and PM10 follow a seasonal temporal variability pattern, having reduced concentrations than during pre-lockdown period, with respectively (PM2.5: with 28 % for the first COVID-19 wave lockdown; 20.7 % for the second COVID-19 wave with partial lockdown and with 23.2 % for the third COVID-19 wave; PM10: recorded reductions of 26 % for the first and the third COVID-19 waves and with 22 % for the second COVID-19 wave) than values recorded during COVID-19 pre-lockdown period. Similar values in different European countries have been reported by other studies (Coccia, 2021b).

Daily mean of ground level average ozone concentrations follow also a seasonal pattern variation, but the concentrations during the three COVID-19 waves were increased in comparison with pre-lockdown period by the following factors: during lockdown and first wave period was an increase of 2.98 factor (explained by traffic –and industrial related sources reduction and partially by spring seasonality), during Heat Wave period the increase of O3 was by a factor of 1.47 (attributed to summer seasonality and traffic-related sources), during second wave the increase of O3 was by a factor of 1.92, and during third wave the increase of O3 was by a factor of 1.44.

During the entire investigated period in this study, mean NO2 ground level of daily average concentrations recorded decreased values as compared with the pre-lockdown period as follows: during first wave COVID-19 lockdown of 53 %, during heat waves period with 43 %, during the second COVID-19 wave with 24 %, and during the third COVID-19 wave with 20 %, explained by traffic-related sources reduction, seasonal inversely variation pattern of NO2 with O3 during summer season, when daily ground level NO2 concentrations record minimum values.

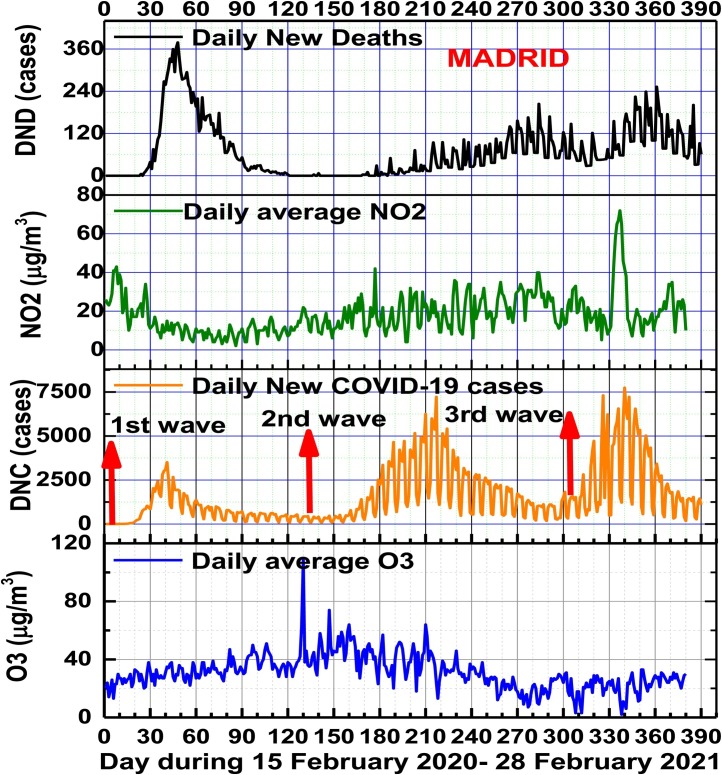

The anthropogenic emission sources that were affected by the lockdown during the first COVID-19 wave and the implementation of other sanitary restrictions during the second and the third COVID-19 waves are mostly on-road mobile sources such as motor vehicles, and to a lesser extend the aircraft and industrial emissions. Like was expected that the main primary air pollutants from these combustion sources, nitrogen oxides (NOx), PM2.5, PM10, carbon monoxide (CO) and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) such as toluene, benzene, xylenes were decreased. But in case of ozone, a secondary pollutant, the effect can be complex and the level can increase or decrease depending on the location, due to interaction of meteorology driving the dispersion of primary pollutants NOx, VOCs and the photochemical reactions forming the ozone levels across the Madrid region. Fig. 2 presents temporal patterns of daily average ground levels of O3 and NO2 concentrations during 15 February 2020 – 28 February 2021and their impacts on the daily new COVID-19 infections (DNC) and daily new COVID-19 deaths (DND) during the three COVID-19 waves. As Fig.2 shows, during the second and the third COVID-19 waves, the daily DND cases were lower than in the first wave, because air quality was improved and also the clinical severity of the last variants of SARS-CoV-2 infections has declined significantly. This is reflecting the impact of sanitary measures implementation like as social distancing, wider face masking, improved medication treatments, or vaccination during the late third wave. From Table 2 is clear that the DNC confirmed positive cases were higher for the second and third waves than of the first wave, respectively of 3.03 and 2.39, possible attributed to new SARS-CoV-2 variants increased virulence and human contacts. In case of fatalities, DND cases in Madrid region registered the highest value during the first COVID-19 wave, while for the second and third waves the number of deaths represented respectively 53.3 % and 78.9 % of the first COVID-19 deaths, February 2021 was the month with the highest number of Daily New Covid-19 Deaths since the first wave of the pandemic last spring 2020.

Fig. 2.

Temporal patterns of daily average ground levels of O3 and NO2 concentrations in relation with Daily New Confirmed COVID-19 cases (DNC) and Daily New COVID-19 Deaths (DND) cases during the three COVID-19 pandemic waves in Madrid.

Table 2.

Recorded (at 28 February 2021) Daily New COVID-19 (DNC) and Daily New COVID-19 Deaths (DND) in Madrid metropolitan region during the three COVID-19 waves.

| Number of cases | First COVID-19 wave 15.02.2020- 15.06.2020 | Second COVID-19 wave 10.08.2020–30.11.2020 | Third COVID-19 wave 01.12.2020–28.02.2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily New COVID-19 (DNC) | 92,602 | 280,673 | 222,114 |

| Daily New COVID-19 Deaths (DND) | 11,134 | 5,933 | 8,795 |

As Table 3 presents, during entire studied period 15 February 2020- 28 February 2021 with all three COVID-19 waves, Spearman rank correlation coefficients and p values between COVID-19-incidence cases are negative correlated with daily average ground level ozone concentrations and positive correlated with daily average of nitrogen dioxide ground level concentrations for analyzed metropolitan area Madrid region. For each COVID-19 waves period results are different (namely positive correlation for O3 and negative correlation for NO2 during the first COVID-19 wave, and invesely correlations for the second and the third waves).

Table 3.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients and p values between COVID-19-incidence cases and daily average main gaseous air pollutants concentrations and main climate variables for investigated metropolitan area Madrid region during entire period 15 February 2020- 28 February 2021.

| MADRID | Air Pollutant |

Climate parameter |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 -incidence | Ozone (μg/m3) |

Nitrogen dioxide (μg/m3) |

PBL height (m) |

Air Temperature T (oC) |

Relative Humidity RH % |

Wind speed Intensity Km/h |

||||||

| r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | |

| Total COVID-19 cases | −0.45 | 0 | 0.37 | p < 0.01 | −0.53 | 0 | −0.52 | 0 | 0.35 | p < 0.01 | 0.39 | p < 0.01 |

| Daily New cases (DNC) | −0.23 | p < 0.01 | 0.27 | p < 0.01 | −0.23 | p < 0.01 | −0.22 | p < 0.01 | 0.26 | p < 0.01 | 0.12 | p<0.05 |

| Daily New Deaths (DND) | −0.43 | p < 0.01 | 0.18 | p < 0.01 | −0.50 | 0 | −0.56 | 0 | 0.66 | 0 | −0.20 | p < 0.01 |

| Total Deaths | −0.39 | p < 0.01 | 0.35 | p < 0.01 | −0.39 | p < 0.01 | −0.35 | p < 0.01 | 0.33 | p < 0.01 | 0.40 | p < 0.01 |

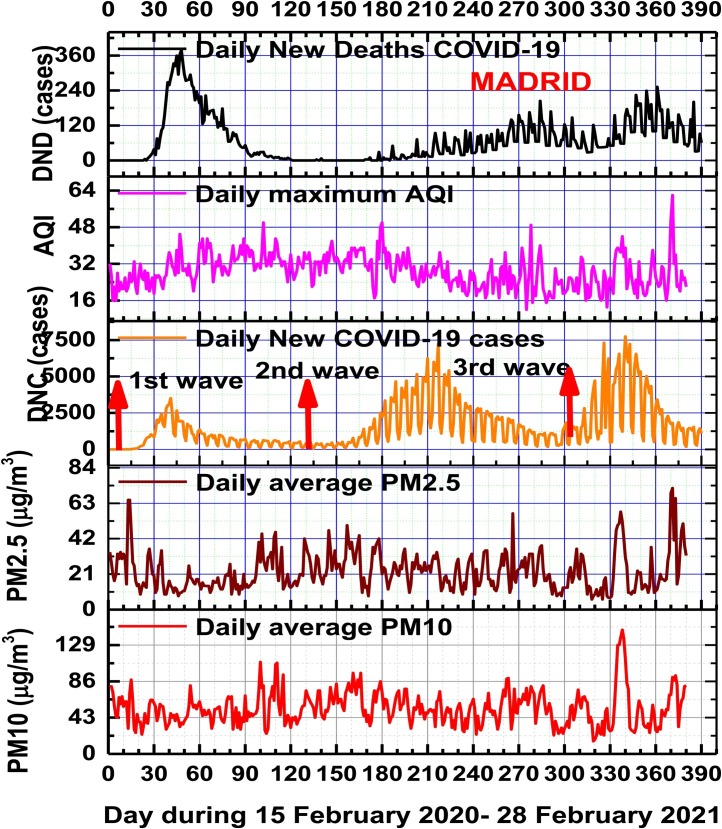

During the all three COVID-19 waves, Spearman rank correlation coefficients and p values between COVID-19-incidence cases (DNC and DND) and PM2.5, PM10 and AQI were direct and low correlated. The results highlight the fact that urban ground surface level of air pollution with gaseous toxic especially NO2 may enhance COVID-19 incidence cases and fatality rates in Madrid metropolitan region.

Like other studies (Collivignarelli et al., 2021; Linares et al., 2021) this research found a positive high correlation of NO2, with the incidence and mortality of COVID-19 in Madrid. Also, values of daily average of PM10 and O3 concentrations in Madrid were greater on the days with Saharan dust intrusion (Linares et al., 2021). Was found a negative association among the ground levels of O3 and the number of new cases of COVID-19 incidence (DNC and DND), that can be attributed to decreased conversion of nitrogen oxide to ozone in urban large areas, a phenomenon previously recorded in highly trafficked areas. Ozone is a potential oxidizer and pulmonary irritant causing an inflammatory response in the lungs as well as a cascade of subsequent responses (Arjomandi et al., 2018; Fuller et al., 2020; Uetake et al., 2019). As a highly reactive exogenous oxidant, NO2 can induce inflammation and enhance oxidative stress, generating reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, which may eventually deteriorate the cardiovascular and immune systems, being a comorbidity factor in case of SARS-CoV-2 viral infections.

The trends between O3 and NOx are strongly anti-correlated, showing that the O3 is strongly depressed by high NOx (Gao et al., 2017). According with several studies in the field (Wang et al., 2020a,b,c; Chen et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020a,b,c; Cohen, Kupferschmidt, 2020), the presence of existing comorbidities associated with pacients’ age, immunity system, sex, genetic and nutritional status, etc., might be essential factors for the aetiology and severity of COVID-19 symptoms. The role of pre-existing immune disorders induced by long- term or short-term exposure to high ground levels of air pollutants (gaseous and PM) contribute to the impressive SARS-CoV-2 lethality in Madrid (Baldasano, 2020; Aleta, Moreno, 2020; Sarkodie, Owusu, 2020).

As can be seen in Fig. 3 , temporal patterns of DNC and DND cases in Madrid metropolitan area in this study, this pandemic is ongoing and air pollution is a dominant environmental factor which must be considered in future COVID-19 waves. In good accord with existing literature in the field, the results obtained in this study suggest that high ground levels of air pollutants concentrations, and especially NO2 and PM2.5 and PM10 are related to the incidence and severity of COVID-19 in Madrid (Casado-Aranda et al., 2021). Public health actions are needed to protect population from COVID-19 disease in Madrid metropolitan area with historically high NO2 and O3 exposure. Also, these results serve to support health measures that minimize population exposure on days with high concentrations of particulate matter due to dust advection from the Sahara.

Fig. 3.

Temporal patterns of daily average ground levels of PM2.5, PM10 concentrations and Air Quality Index (AQI) in relation with Daily New Confirmed COVID-19 cases (DNC) and Daily New COVID-19 Deaths (DND) cases during the three COVID-19 pandemic waves in Madrid.

4.2. Climate variables impact on COVID-19 waves

Climate variables provide an useful explanation for the COVID-19 pandemic disease spread. Several scientific studies demonstrated that the changes of urban air pollution levels with aerosols and bioaerosols (fungi, bacteria and viruses) are function of multiple factors among which anthropogenic and natural emission sources, the chemical composition of the atmosphere, meteorological conditions, relationship with Planetary Boundary Layer height (Zhao et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020a,b), synoptic atmospheric circulation patterns, micro- and meso-climatic features of the environment (Zhao et al., 2018) and geomorphology of the city.

In order to describe the meteorological conditions over Madrid metropolitan region, which can be involved in the diffusion and severity of COVID-19 viral infection disease during different seasons over investigated time period (15 February 2020 - 28 February 2021), have been analyzed the temporal patterns of daily average climate parameters (air temperature, relative humidity, atmospheric pressure, precipitation rate, wind speed intensity, Planetary Boundary Layer height). The main results in Table 3 show during one year period, mean of daily average air temperature (15.14 ± 8.5)oC in the range of (-17.8–32.4) oC and relative humidity (62.06 ± 20.42)% in the range of (21.4–97.8)% variables have the strongest relation with Total COVID-19 confrmed infections and Daily New Deaths cases in Madrid region. For the entire investigated period (15 February 2020 – 28 February 2021), COVID-19 disease transmission was inversely correlated with daily average air temperature and direct correlated with daily average air relative humidity. Table 4 presents Spearman correlation coefficients and p values between climate variables and daily average ground-levels O3, NO2, PM2.5, PM10 concentrations and AQI during one year period of COVID-19 in Madrid. The results for Madrid region show a positive and high correlations of ground levels of ozone concentration with air temperture and, Planetary Boundary Layer heights,and wind speed intensity and inversely correlations with air relative humidity and oposite relationship of the ground nitrogen dioxide concentration levels. Particulate matterials (PM2.5 and PM10) and AQI present inverse correlations with PBL and air temperature and wind speed intensity, and low correlations with air relative humidity. The findings are well correlated eith the existing literature (Adams, 2020; Ahmadi et al., 2020; Poole, 2020), having a high impact on COVID-19 spread.

Table 4.

Spearman correlation coefficients and p values between climate variables and daily average ground-level O3, NO2, PM2.5, PM10 concentrations and AQI during investigated period 15 February 2020 – 28 February 2021 for Madrid region.

| Daily average climate variable | 15 February 2020 – 28 February 2021 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O3 (μg/m3) |

NO2 (μg/m3) |

PM10 (μg/m3) |

PM2.5 (μg/m3) |

AQI |

||||||

| r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | |

| PBL height (m) | 0.85 | 0 | −0.69 | 0 | −0.30 | <0.01 | −0.30 | <0.01 | −0.28 | <0.01 |

| Temperature (oC) | 0.75 | 0 | −0.67 | 0 | −0.21 | <0.01 | −0.11 | 0.13 > 0.05 | −0.16 | 0.04 < 0.05 |

| Relative Humidity (%) | −0.69 | 0 | 0.29 | <0.01 | 0.27 | <0.01 | 0.09 | 0.2 > 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.2 > 0.05 |

| Wind speed (km/h) | 0.36 | <0.01 | −0.48 | <0.01 | −0.32 | <0.01 | −0.40 | <0.01 | −0.05 | 0.4 > 0.05 |

For the first COVID-19 pandemic wave the statistical analysis found a direct correlation of COVID-incidence with air temperature (r = 0.76; p = 0) for Total COVID-19 confirmed cases, (r = 0.80; p = 0) for Total Deaths and invers correlation with air relative humidity (r= -0.24; p < 0.01) for Total COVID-19 confirmed cases, and (r= -0.37; p < 0.01) for Total Deaths, while for the second and third waves the rank Spearman correlation coefficients between COVID-19 incidence cases (DNC and DND) were inversely correlated with air temperature and direct correlated with relative humidity. On over one year study period (15 February 2020 – 28 February 2021) daily average temperature is inversely correlated with daily average relative humidity (Spearman correlation coefficient being r= -0.81, and p = 0).

According to results of this study, cold weather is much more susceptible for the daily new COVID viral infection transmission in Madrid than is case of good weather conditions. Hot summer 2020 conditions under heat waves events explained recorded reduced rates of the COVID-19 disease transmission during 15 June- 10 August 2020 in Madrid. Our results are in good agreement with other studies, which demonstrated that air temperature and relative humidity parameters are involved in the transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 viral infection, playing an important role in COVID-19 mortality rate (Byun et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020; Adams, 2020; Ahmadi et al., 2020; Poole, 2020).

Although most studies indicated an inverse association of viral community spread with temperature (Srivastava, 2021; Bezabih et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020a,b; Benedetti et al., 2020; Bolaño-Ortiz et al., 2020; Sanchez-Lorenzo et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2020a,b) some findings reported a positive relationship between temperature and the number of COVID19 cases (Zhu, Xin, 2020; Bashir et al., 2020a,b; Zoran et al., 2020b; Xie and Zhu, 2020; Pani et al., 2020; Islam et al., 2021) and few studied found no correlation (Briz-Redón, Serrano-Aroca, 2020). Daily relative humidity is an essential meteorological variable of SARS-CoV-2 airborne diffusion, being involved in the formation and size of aerosol droplets, used as a medium to infect new hosts (Yang and Marr, 2012; Yang et al., 2012, 2020). Some inconsistent findings in the relationship between air relative humidity and local transmission of SARS-CoV-2 were reported as follows: negative correlation (Jüni et al., 2020; Metelmann et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Şahin, 2020; Mangla et al., 2020; Zoran et al., 2020b; Menebo, 2020) and positive correlations (Ozyigit, 2020; Oliveiros et al., 2020; Pani et al., 2020) and few studied found no correlation.

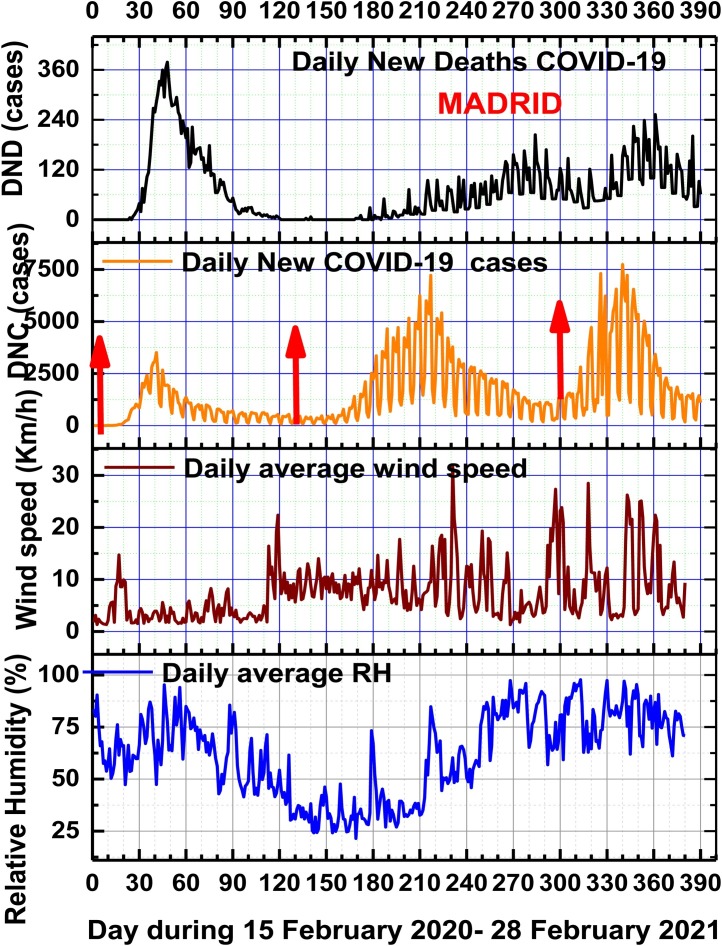

Among the other climate variables, daily average wind speed intensity of mean value of (7.55 ± 5.60) km/h in the range of (1.29–31.7) km/h, had a weakly inverse relationship with the recorded Daily New COVID-19 Deaths (r= -0.20 with p < 0.01) and positive relationship with Total COVID-19 confirmed, Daily New COVID-19 confirmed and Total COVID-19 Deaths cases, as can be seen in Table 3.

Among the most important climate variable, the Planetary Boundary Layer height (PBL) is related to the vertical mixing, affecting the dilution of pollutants and bioaerosols (bacteria, fungi and viruses) near the ground. Also, PBL may be responsible of pandemic SARS-CoV-2 viral infection diffusion through airborne route. Lower levels of PBL heights may be associated with increased viral pathogens concentrations at the near surface, and higher transmission rates.

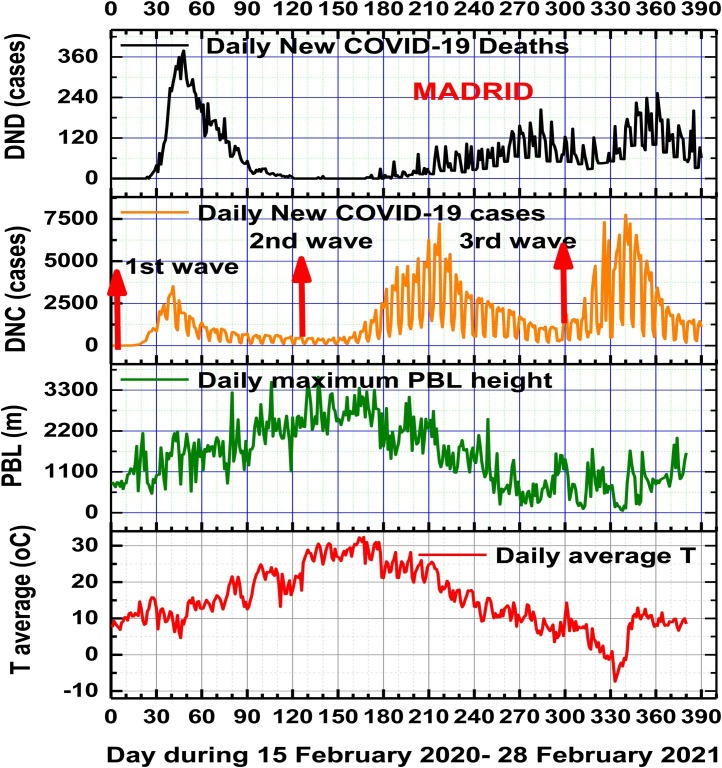

The mean value of daily maximum PBL height level during all investigated period in Madrid was of (1529.29 ± 832.14) m in the range of (132–3651) m. Temporal patterns of the daily averge air temperature, Planetary Boundary Layer height, relative humidity and wind speed intensity in relation with dynamics of the coronavirus disease waves in Madrid can be seen in Fig. 4 and respectively in Fig. 5 . Daily maximum solar radiation and precipitation rates contribution might be reflected in the daily average temperature and also in the atmospheric pressure. During each of COVID-19 pandemic wave the means of daily maximum PBL heights in Madrid recorded different values, namely: for the first COVID wave (1613.82 ± 611.88) m in the range of (516–3514) m; for the second COVID wave (1412 ± 729.72) m in the range of (174–3117) m; for the third COVID wave (837.41 ± 455.43) m in the range of (55–2012) m.

Fig. 4.

Temporal patterns of daily average air temperature, and Planetary Boundary Layer height in relation with Daily New COVID-19 positive cases (DNC) and Daily New COVID-19 Deaths (DND) cases during the three COVID-19 pandemic waves in Madrid.

Fig. 5.

shows temporal patterns of daily average air relative humidity and wind speed intensity in relation with Daily New COVID-19 positive cases (DNC) and Daily New COVID-19 Deaths (DND) cases during the three COVID-19 pandemic waves in Madrid.

The lower values of PBL heights for the third COVID wave may explain the highest Daily New COVID-19 confirmed positive cases and Daily New COVID-19 Deaths recorded in Madrid during that period (1 December 2020- 28 February 2021). We observed significant negative associations between Planetary Boundary Layer heights levels and all COVID-19 incidence cases (Total COVID-19 confirmed positive, Daily New COVID-19, Daily New Deaths and Total Deaths) in Madrid metropolitan region both on entire one year period and for each of the three COVID-19 pandemic waves.

Because COVID-19 disease temporal variability is function of independent air pollution and meteorological seasonal variables (air temperature, relative humidity, Planetary Boundary Layer heights, air pressure, local and regional winds and precipitation rates), is also seasonal sensitive (Miao et al., 2015). Like as other viral infections (human influenza virus, coronaviruses, etc.) SARS-CoV-2 and its variants could exhibit seasonal patterns (Ye et al., 2020; Coccia, 2020c, d; Byun et al., 2021, Bontempi, 2021), and multi-wave patterns.

4.3. Influences of atmospheric pressure field and synoptic atmospheric circulations on COVID-19 waves

Madrid and its metropolitan area has a Mediterranean with transitions to a cold semi-arid climate, with wide thermal amplitude and an annual mean temperature of 13.7 °C. Blocking anticyclone atmospheric circulation systems are particularly common over the Madrid metropolitan region in Spain and Eastern Atlantic. The city of Madrid, often has poor air quality because it is frequently under a stationary anticyclone weather conditions (high pressure/geopotential, low wind intensity) that tend to increase pollution (Garrido-Perez et al., 2018), due to stagnant air masses.

In the last years, several studies conducted in the Madrid region have proved that synoptic atmospheric circulations play a significant role in the spatiotemporal distribution of urban and industrial ground level air pollutants (PM2.5, PM10, O3, NO2) formation and transport at both regional and continental scale (Borge et al., 2018; Russo et al., 2014; López et al., 2019) as well as in the long-distance transport of Saharan dust intrusions (Salvador et al., 2013; Russo et al., 2020; Valverde et al., 2015; Linares et al., 2021). Before the three COVID-19 waves with at least one month, in the mid-troposphere have been recorded highly stable anticyclonic atmospheric conditions characterized by the stationary presence of high pressure systems over Madrid metropolitan region, frequently associated with urban high-pollution episodes and negative impact on human cardiorespiratory and immune systems. Atmospheric pressure is a quite significant factor and could be one of the most related with the virus transmission.

-

•

First COVID-19 wave case

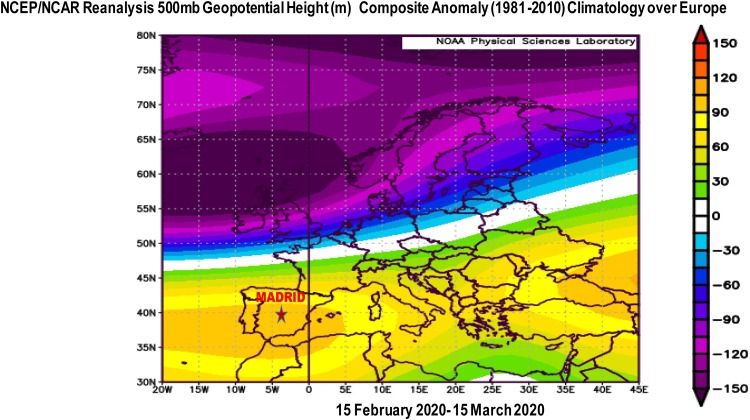

The main synoptic atmospheric circulation pattern during start-up of the first COVID-19 wave in Madrid, during 15 February 2020- 15 March 2020 was characterized by an anomalous anticyclonic system with stable and dry conditions over the western Mediterranean basin and Spain, including Madrid region, as can be seen in Fig. 6 which presents NOAA satellite composite anomaly pattern in the upper troposphere of 500 hPa geopotential height (m) map at 5.5 km height over Europe, as compared to the climatology mean (1981–2010) period during first COVID-19 wave start-up in Italy and Spain (15 February 2020 – 15 March 2020). Geopotential height positive anomalies consist of deviations > 95 m in the geopotential height field from average values, that may have favored the SARS-CoV-2 viral infection transmission, both outdoors and especially indoors.

Fig. 6.

NOAA satellite composite anomaly pattern of 500 hPa geopotential height (m) map over Europe as compared to the climatology mean (1981–2010) period during first COVID-19 wave start-up in Italy and Spain (15 February 2020 – 15 March 2020).

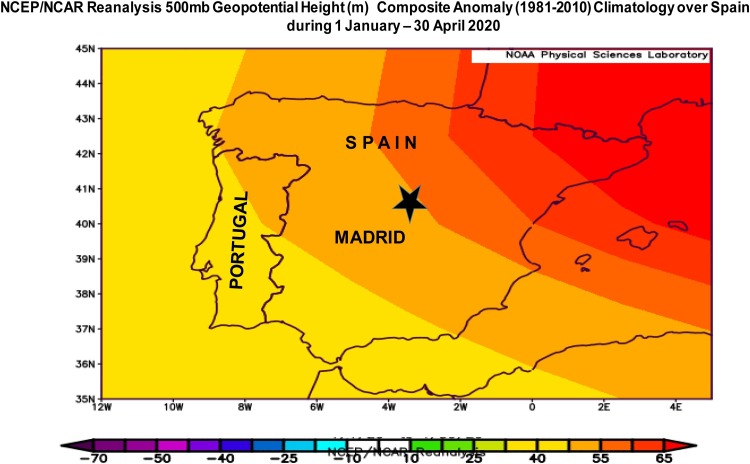

Based on NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis Intercomparison Tool provided by the NOAA/ESRL Physical Sciences Laboratory, Boulder Colorado from their Web site at http://psl.noaa.gov/, from 1 January till the end of April 2020, were recorded positive anomalies of geopotential height over Spain and Madrid region (Fig. 7 ), which explain the high rate of COVID-19 incidence and mortality during the first COVID-19 pandemic wave.

Fig. 7.

NOAA satellite composite anomaly pattern of 500 hPa geopotential height (m) map over Spain as compared to the climatology mean (1981–2010) period during first COVID-19 wave start-up in Spain (1 January 2020 – 30 April 2020).

Also, the pre-existing high levels of air pollutants over Madrid metropolitan region during January–February 2020 months, can explain increased susceptibility of people's immune and cardiorespiratory systems to new viral infections COVID-19 and the high rate of fatalities recorded during the first wave.

-

•

Second COVID-19 wave case

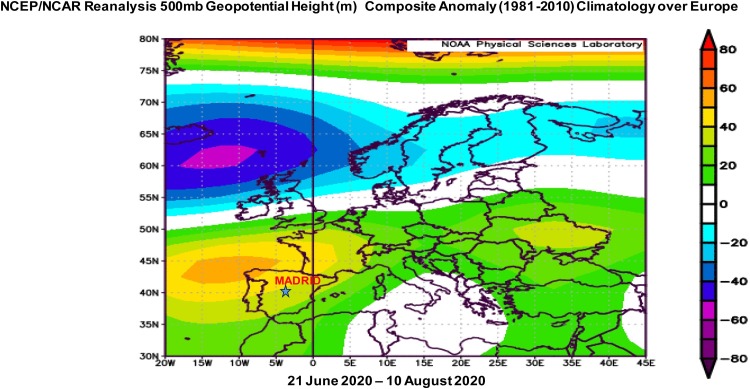

Before and during the second COVID-19 wave were also recorded anomalous synoptic anticyclonic blocking atmospheric circulations, with positive anomalies of isobaric surface heights of geopotential at 500 mb over Euorpe, associated with favorable stability conditions for the fast diffusion of the SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 8 ).

Fig. 8.

NOAA satellite composite anomaly pattern of 500 hPa geopotential height (m) map over Europe as compared to the climatology mean (1981–2010) period before the second COVID-19 wave start-up in Madrid.

The comparative analysis of the first COVID-19 wave star-up in Madrid under similar anticyclonic weather conditions with geopotential height anomalies, increase of ground level ozone and decreased air relative humidity may support the hypothesis that the strong atmospheric stability and associated hot summer temperatures under heat waves, and dry conditions are main environmental factors related with the second COVID-19 wave start-up.

-

•

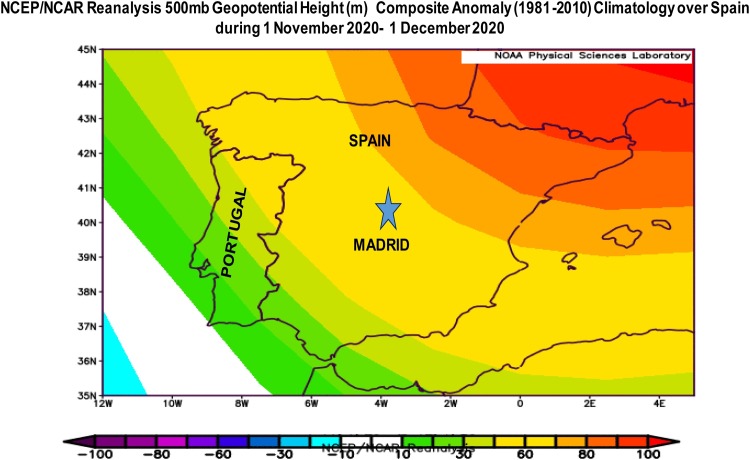

Third COVID-19 wave case

Before and during the third COVID-19 wave were also recorded anomalous synoptic anticyclonic blocking atmospheric circulations, with positive anomalies of isobaric surface heights of geopotential at 500 mb over Spain and Madrid (Fig. 9 ), associated with favorable stability conditions for the fast transmission of the SARS-CoV-2. The related higher incidence and severity of COVID-19 disease in Madrid region during the third wave can be explained through existing stagnant atmospheric conditions favourable for the main air pollutants (PM2.5 and PM10, and especially O3 and NO2) accumulation near the ground. Anyway, clinically severe cases and lethality rates were lower than in first COVID-19 wave (Soriano et al., 2021).

Fig. 9.

NOAA satellite composite anomaly pattern of 500 hPa geopotential height (m) map over Spain as compared to the climatology mean (1981–2010) period before the third COVID-19 wave start-up in Madrid (1 November 2020 – 1 December 2020).

These results serve to support the important role of climate factors seasonality in relation with the existing synoptic atmospheric meteorological patterns, before and during all COVID-19 waves, that provide optimal conditions for the SARS-CoV-2 and its new variants transmission in Madrid metropolitan region. In good agreement with existing literature in the field (Sanchez-Lorenzo et al., 2021; Zoran et al., 2020a), our analysis of collected data and results show that urban air polution, climate and synoptic meteorological patterns may play a significant role in the airborne transmission and spread of the coronavirus.

COVID-19 disease incidence analysis over time range of (15 February 2020 – 28 February 2021) supports the hypothesis that possible SARS-CoV-2 viral infection airborne pathway transmission is highly dependent on associated air pollution, climate and regional atmospheric circulation seasonality patterns among which air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed intensity, atmospheric pressure, precipitation rate. Was observed that COVID-19 seasonality is much more intense at higher latitudes, where are recorded grater seasonal amplitudes of meteorological variables (Liu et al., 2021).

The associated conditions that lead to pandemic levels of COVID-19 depend on the disease transmission pathways, environmental factors (air pollution and climate, waste waters, etc.) seasonality favoring the growth, multiplication and spread of SARS-CoV-2 pathogens. Rapid urbanization, industrialization, globalization and migration of people must be also considered additional factors possibly escalating the risk of disease incidence among vulnerable population during the outbreak. This study suggests that the difference in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic waves periods can be also the result of different policies adopted both at the regional and at the municipality level, considering that timely and properly intervention strategies such as intensive contact tracing followed by quarantine and isolation can effectively reduce the transmission risk of the new SARS-CoV-2 variants.

5. Discussion

The first COVID-19 wave recorded in Madrid started at mid February 2020 and peaked at the end of March with high fatality rate, being followed by a progressive decrease with very few positive confirmed cases and very few fatalities in May and almost no deaths in June. The number of new infected cases fluctuated upward from mid-July – beginning of August with COVID-19 s wave start-up until a sharp increase in mid October 2020. During the second COVID-19 wave, much longer than previous one have been recorded few daily new deaths but higher number of daily new positive confirmed COVID-19 cases than for the first wave. Due to relaxation of restrictions in December and the rise of social interaction over winter holidays the third COVID-19 wave, came hot on the heels of the second one, which was seen in the autumn. The third wave considered to start at the beginning of December 2020 and peaked at the mid January 2021 caused a significantly higher number of COVID-19 confirmed positive cases than the first two waves but regarding fatalities, fewer than of first wave and higher than of second wave as can be seen in the graphs in Fig. 2, Fig. 3. During the first wave, there was a sharp spike in cases, but the rise has been slower in the third wave, and will likely take longer to fall, given that coronavirus restrictions are less strict now than they were last spring, when the Spanish government ordered a full home lockdown. The spread and the decay duration of the three COVID-19 pandemic waves (Diao et al., 2021) in Madrid metropolitan region can be attributed to differences in medical and sanitary governmental intervention actions and regional policies, as well as the seasonality of climate variables like as air temperature, relative humidity and synoptic meteorological patterns.

Also, the differences between the COVID-19 waves can be attributed to different infectivity rates of new variants of SARS-CoV-2. This was the case of the second COVID-19 wave, that emerged in early summer 2020 in Madrid and Spain, that was sanitary better managed, through greatly increased of response capacities after the first wave of this virus. Another factor that might have contributed to the decay in the fatalities rates during the second and third waves in comparison with the first infection wave may be attributed to the improvement in environmental conditions due to sanitary measures comparable with pre-lockdown period, and adopting of different preventive health strategies and better policies (Jin et al., 2021) that reduce the health risks associated with COVID-19.

One of the relevant result of this study is the comparative analysis between environmental variables patterns (air pollutants :PM2.5, PM10, O3 and NO2, AQI; and climate variables : air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed intensity, air pressure, Planetary Boundary Layer heigh) and the COVID-19 multi-waves incidence start-up. There are several physico-chemical-atmospheric mechanisms that could explain the existence of these associations (Domingo and Rovira, 2020; Coccia, 2021b; Iqbal et al., 2021).

The chemodynamics of SARS-CoV-2 virions and PM interactions may be responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic spreading during several seasons, which provides a strong basis for explaining reported correlations between air pollution episodes during anticyclonic stagnant periods in densely urban regions and new COVID-19 waves (Coccia, 2021a, c).

Like other previous studies (Liu et al., 2021) we found that COVID-19 seasonality in relationship with climate variables seasonality alone are not sufficient to stop the coronavirus transmission in the warm season, this finding has important implications in the control and prevention of COVID-19 transmission.

Lower levels of Planetary Boundary Layer heights and low wind speeds reduce the dispersion of atmospheric pollutants in the lower atmosphere, which can act as SARS-CoV-2 carriers in the air and sustain the transmission of COVID-19 disease in the environment (Coccia, 2020a; Byun et al., 2021).

Results of this study for Madrid metropolitan region are in good agreement with other studies for European cities (Coccia, 2021c; Linares et al., 2021;), suggesting that the fast transmission of COVID-19 disease and daily new confirmed positive cases (DNC) and deaths (DND) is associated with high levels of air pollution with PM10 and NO2, lower daily average air temperature and wind speed intensity.

In conclusion seasonal variability of climate and air pollution parameters can explain some seasonality and important aspects in the COVID-19 disease transmission (Rahimi et al., 2021), but epidemiological measures of social distance are essential. Also, the lessons learned from the pandemic in synergy with environmental factors can help to define proper actions to mitigate climate change.

6. Conclusions and policy implications

Following concerns of the new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 that might be more transmissible, environmental conditions among several major European cities, Madrid Community must consider the effects of existing heavy air pollution by particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) and ground level ozone (O3) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), which can contribute to high rate of SARS-CoV-2 viral infection spread and severity of the coronavirus disease(COVID-19) pandemic.

The findings of this study suggest that local air pollution levels in Madrid metropolitan region are actively controlled by regional meteorological formation of extensive stationary anticyclones, with one month before of each of the three COVID-19 pandemic waves, with blocking effects over the region and higher COVID-19 incidence infection rates. This study considered also synergy effects of climate and air pollution factors impacts and possible correlation among these variables with regional atmospheric circulation and COVID-19 waves start-up. As the airborne microbial temporal pattern is most affected by seasonal changes, Planetary Boundary Layer height, air temperature, relative humidity, air pressure and wind speed intensity variables have a strong impact on COVID-19 spread seasonality with higher incidence during winter-spring and lower incidence during summer seasons. Comparative analyses of environmental stressors variability between COVID-19 waves in Madrid offer insights into how urban decision-makers responses can be made more effective and timely and how health and social care systems could be made more resilient. Present study underlines the need of considering impact of urban densely populated areas in relation with seasonal variability of environmental factors in COVID-19 pandemic intervention strategies. Also, these results may help to understand the characteristics of the COVID-19 waves in relation with climate and anthropogenic factors and associated risks of SARS-CoV-2 viral infections in the Mediterranean region and in Europe. In addition in the context of ongoing COVID-19 disease worldwide, Spain must adopt anti-epidemic policies and limit the urban road-traffic in Mdarid metropolitan region, that is the main source of air pollution. Outbreak management in COVID-19 multi-waves is of great importance for public health and safety. Early warning strategies to control the spread of the pandemic disease must be based on proper information on the environmental factors, that could aggravate cardiovascular and respiratory conditions. Also, public health measures could include informative notices to especially vulnerable population groups such as the elderly and people with previous cardio-respiratory and neurological pathologies, advising them to limit their both short-term and long-term exposure in outdoor environments during extreme climate events and high pollution episodes. Further studies are needed to confirm our findings in order to implement early sanitary alert protocols and ensure equity and responsiveness to local and regional contexts, essential steps on the difficult way ahead to ending the COVID-19 pandemic.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Maria Zoran: Conceptualization; Methodology, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Roxana Savastru: Methodology, Validation, Review. Dan Savastru: Methodology, Validation, Review. Marina Tautan: Methodology, Validation. Laurentiu Baschir: Visualization; Software. Daniel Tenciu: Visualization; Data collection.

Consent for publication

All the co-authors consent the publication of this work.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Romanian Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization /Program NUCLEU Contract 18N/08.02.2019/2021. We are thankful to NOAA/OAR/ESRL PSD, Boulder, Colorado, USA for providing useful climate data.

References

- Adams M.D. Air pollution in Ontario, Canada during the COVID-19 state of emergency. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi M., Sharifi A., Dorosti S., et al. Investigation of effective climatology parameters on COVID-19 outbreak in Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleta A., Moreno Y. Evaluation of the potential incidence of COVID-19 and effectiveness of containment measures in Spain: a data-driven approach. BMC Med. 2020;18(2020):157. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01619-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin M., Sorour M.K., Kasry A. Comparing the binding interactions in the receptor binding domains of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:4897–4900. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c01064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariya P.A., Amyot M. New directions: the role of bioaerosols in atmospheric chemistry and physics. Atmos. Environ. 2004;38:1231–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Arjomandi M., et al. Respiratory responses to ozone exposure. MOSES (The multicenter ozone 379 study in older subjects) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;197:1319–1327. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1613OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artínano B., Salvador P., Alonso D.G., Querol X., Alastuey A. Anthropogenic and natural influence on the PM10 and PM2.5 aerosol in Madrid (Spain). Analysis of high concentration episodes. Environ. Pollut. 2003;125(3):453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(03)00078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadi S., Bouvier N., Wexler A.S., Ristenpart W.D. The coronavirus pandemic and aerosols: Does COVID-19 transmit via expiratory particles? Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2020;54(6):635–638. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2020.1749229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baay M., Lina B., Fontanet A., et al. SARS-CoV-2: virology, epidemiology, immunology and vaccine development. Biologicals. 2020;66:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakadia B.M., Boni B.O.O., Ahmed A.A.Q., Yang G. The impact of oxidative stress damage induced by the environmental stressors on COVID-19. Life Sci. 2021;264:18653. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhshandeh B., Sorboni S.G., Javanmard A.-R., et al. Variants in ACE2; potential influences on virus infection and COVID-19 severity. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2021;90:10477. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baklanov A., Molina L.T., Gauss M. Megacities, air quality and climate. Atmos. Environ. 2016;126:235–249. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.11.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldasano J.M. COVID-19 lockdown effects on air quality by NO2 in the cities of Barcelona and Madrid (Spain) Sci. Total Environ. 2020;7411 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballabio D., Bolzacchini E., Camatini M.C. Particle size, chemical composition, seasons of the year and urban, rural or remote site origins as determinants of biological effects of particulate matter on pulmonary cells. Environ. Pollut. 2013;176:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreca A.I. Climate change, humidity, and mortality in the United States. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2012;63(1):19–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir M.F., Bilal B.M., Komal B. Correlation between environmental pollution indicators and COVID-19 pandemic: a brief study in Californian context. Environ. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir M.F., et al. Correlation between climate indicators and COVID-19 pandemic in New York, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti F., et al. Inverse correlation between average monthly high temperatures and COVID-19-related death rates in different geographical areas. J. Transl. Med. 2020;18:251. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02418-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezabih Y.M., et al. Correlation of the global spread of coronavirus disease-19 with atmospheric air temperature. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.27.20115048. 2020.05.27.20115048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop K., Holmes R., Sheehy A., Malim M. APOBECmediated editing of viral RNA. Science. 2004;305(5684):645. doi: 10.1126/science.1100658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolaño-Ortiz T.R., et al. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 through Latin America and the Caribbean region: a look from its economic conditions, climate and air pollution indicators. Environ. Res. 2020;191 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi E. The europe second wave of COVID-19 infection and the Italy “strange” situation. Environ. Res. 2021;193 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi E., Vergalli S., Squazzoni F. Understanding COVID-19 diffusion requires an interdisciplinary, multi-dimensional approach. Environ. Res. 2020;188 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borge R., Artínano B., Yagüe C., Gomez-Moreno F.J., Saiz-Lopez A., Sastre M., Narros A., García-Nieto D., Benavent N., Maqueda G., Barreiro M., de Andrés J.M., Cristóbal A. Application of a short term air quality action plan in Madrid (Spain) under a high-pollution episode - Part I: diagnostic and analysis from observations. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;635:1561–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borge R., Requia W.J., Yagüe C., Jhun I., Koutrakis P. Impact of weather changes on air quality and related mortality in Spain over a 25 year period [1993–2017] Environ. Int. 2019;133(B) doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch B.J., van der Zee R., de Haan C.A.M., Rottier P.J.M. The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J. Virol. 2003 doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.16.8801-8811.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers R.M., Lauber C.L., Wiedinmyer C., Hamady M., Hallar A.G., Fall R., Knight R., Fierer N. Characterization of airborne microbial communities at a high-elevation site and their potential to act as atmospheric ice nuclei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:5121–5130. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00447-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers R.M., Clements N., Emerson J.B., Wiedinmyer C., Hannigan M.P., Fierer N. Seasonal variability in bacterial and fungal diversity of the near-surface atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:12097–12106. doi: 10.1021/es402970s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briz-Redón Á., Serrano-Aroca Á. A spatiotemporal analysis for exploring the effect of temperature on COVID-19 early evolution in Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun W.S., Heo S.W., Jo G., Kim J.W., Kim S., Lee S., Park H.E., Baek J.-H. Is coronavirus disease (COVID-19) seasonal? A critical analysis of empirical and epidemiological studies at global and local scales. Environ. Res. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.110972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cáliz J., Triadó-Margarit X., Camarero L., Casamayor E.O. A long-term survey unveils strong seasonal patterns in the airborne microbiome coupled to general and regional atmospheric circulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:12229–12234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1812826115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C., Jiang W., Wang B., Fang J., Lang J., Tian G., Jiang J., Zhu T. Inhalable microorganisms in Beijing’s PM2.5 and PM10 pollutants during a severe smog event. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48(3):1499–1507. doi: 10.1021/es4048472. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Chen M., Dong D., Xie S., Liu M. Environmental pollutants damage airway epithelial cell cilia: implications for the prevention of obstructive lung diseases. Thorac. Cancer. 2020;11:505–510. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraturo F., Del Giudice C., Morelli M., Cerullo V., Libralato G., Galdiero E., Guida M. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in the environment and COVID-19 transmission risk from environmental matrices and surfaces. Environ. Pollut. 2020;265(B) doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carugno M., Dentali F., Mathieu G., Fontanella A., Mariani J., Bordini L., Milani G.P., Consonni D., Bonzini M., Bollati V., Pesatori A.C. PM10 exposure is associated with increased hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis among infants in Lombardy, Italy. Environ. Res. 2018;166:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casado-Aranda L.A., Sánchez-Fernández J., Viedma-del-Jesús M.I. Analysis of the scientific production of the effect of COVID-19 on the environment: A bibliometric study. Environ. Res. 2021;193 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cevik M., et al. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV viral load dynamics, duration of viral shedding, and infectiousness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2021;2:e13–e22. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30172-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Zhang L., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuvochina M.S., Marie D., Chevaillier S., Petit J.-R., Normand P., Alekhina I.A., Bulat S.A. Community variability of bacteria in alpine snow (Mont Blanc) containing Saharan dust deposition and their snow colonisation potential. Microbes Environ. 2011;26(3):237–247. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.me11116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciencewicki J., Jaspers I. Air pollution and respiratory viral infection. Inhal Toxicology. 2007;19(14):1135–1146. doi: 10.1080/08958370701665434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CM, 2021. www.comunidad.madrid/sites/default/files/doc/sanidad/210314_cam_covid19.pdf.

- Coccia M. An index to quantify environmental risk of exposure to future epidemics of the COVID-19 and similar viral agents: theory and Practice. Environ. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]