Abstract

To study the effect of silymarin on the Interleukin-6 (IL-6) level, size of endometrioma lesion, pain, sexual function, and Quality of Life (QoL) in women diagnosed with endometriosis. This randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial was performed on 70 women with endometriosis which was divided into two groups of intervention and control. The intervention was 140 mg silymarin (or matching placebo) administered twice daily for 12 weeks. The volume of endometrioma lesions, the level of IL-6 concentration in serum, pain, sexual function, and QoL were analyzed before and after the intervention. The means of endometrioma volume (P = 0.04), IL-6 (P = 0.002), and pain (P < 0.001) were reduced significantly in the silymarin group after intervention. However, the QoL and female sexual function did not improve substantially in the two groups (P > 0.05). Silymarin significantly reduced interleukin-6 levels, sizes of endometrioma lesions, and pain-related symptoms. The trial has been registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20150905023897N5) on 4th February 2020 (04/02/2020) (https://en.irct.ir/trial/42215) and the date of initial participant enrollment was 2nd March 2020 (02/03/2020).

Subject terms: Endocrinology, Health care, Medical research, Diseases, Reproductive disorders

Introduction

Endometriosis is a debilitating recurrent gynecological disorder characterized by the proliferation of the endometrial tissue in ectopic sites which is most commonly found in the ovaries, affecting approximately 10% of reproductive-aged women1,2. Ovarian endometriosis (OMA) might be accompanied by several pain-related manifestations such as pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and subfertility3. Not only do these discomfort symptoms pose devastating impacts on the Quality of Life (QoL), psychological, social, and sexual life of afflicted women, also these can represent a massive economic burden on patients and the health care system4,5.

Although the accurate pathogenesis of endometriosis remains elusive, several therapeutic modalities for endometriosis are suggested based on its unclear mechanisms. Therefore, Oral Contraceptive Pills (OCPs), progestogens, anti-progestogens, Gonadotrophin-Releasing Hormone analogues (GnRH-a), and surgical therapy, alone or in combination are used for treatment6. Recent studies have addressed the roles of Oxidative Stress (OS) and inflammatory factors in the etiology and improvement of OMA7. Hence, an endometrioma contains a higher level of free iron, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), and inflammatory molecules such as Interleukin (IL)-8, IL-6, Tumor Necrosis Factor-a (TNF-a) compared with those present in peripheral blood or other types of benign cysts8,9. Thus, endometriosis treatment should not be different from that of other inflammatory disorders10.

Silymarin is a unique flavonoid complex derived from the milk thistle plant (Silybum marianum) and consists of a family of flavolignans such as silybins A and B (major bioactive compounds), silychristin, and silydianin11. Silymarin displays potent antioxidant and free radical scavenging abilities and has strong anti-fibrotic properties12,13. The antioxidant mechanism of silymarin results from inducing superoxide dismutase, increasing cellular glutathione content and inhibiting lipid peroxidation, it also is a powerful iron chelator14. Apart from antioxidant effects, silymarin acts an anti-inflammatory agent by inhibiting the migration of neutrophils to the site of inflammation, Kupffer cells, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and transcription factor NF- κB which regulates various genes involved in the inflammatory process15–17. It is also has been reported that silymarin can inhibit the TNF-a, interferon-c, IL-2, and Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS)14. In addition, several in vitro and animal studies have verified the effects of silymarin in decreasing the size and histopathologic grade of the endometrial lesions18–20.

Thus, in light of previous studies on silymarin in other chronic disease and endometrial cells, we explored the relationship between silymarin and OMA in a double-blind, randomized clinical trial looking at the effect of silymarin on cessation of pain-related symptoms in women suffering from OMA.

Materials and methods

Trial design and overview

This study was a phase II, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted in gynecological clinics affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, from 2nd March 2020 (02/03/2020) to 18th May 2021 (18/05/2021). This clinical trial comprised a 12-week treatment period, after which some of the endometriosis-related manifestations were evaluated. This trial conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran, before the commencement of the study on 22nd October 2019 (IR.MODARES.REC.1398.143). In addition to that, it has been registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials in 4th February 2020 (04/02/2020) (IRCT20150905023897N5). All potential study subjects provided written informed consent and were informed about the aims and possible risks of the trial before the study. Not only can all authors attest to the completeness and accuracy of the data and analyses and adherence to the trial protocol, but also they have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Participants

Eligible subjects were women of reproductive age (15–49 years), married, and non-pregnant with a confirmed diagnosis of OMA via transvaginal ultrasonography performed by a single sonologist at the three-dimensional level in the previous five years and currently experiencing moderate to severe pain and receiving 2 mg dienogest daily in last six months [Dienogest as a conservative treatment option manages endometriosis through down-regulating estrogen receptors and constraining the local production of estradiol21].

The pattern recognition using subjective evaluation of Gray-scale and Doppler-ultrasound characteristics based on IOTA rules “an adnexal mass with ground glass echogenicity of the cyst fluid, one to four locules and no papillations with detectable blood flow” and volume (L × D × W × 0.5235) was achieved through the Orsini formula22.

Women would have been excluded if they had suffered from chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, coronary, renal, and hepatic disorders or liver enzyme anomalies. Also, suppose they had taken specific medications like oral contraceptives, anti-depressant and GnRH analogues, or systemic glucocorticoids, with a specified wash-out period for each one based on the period. In that case, they might have a continued effect. In addition, using silymarin or other milk thistle preparations and anti-inflammatory supplements (e.g., vitamin, vitamin E,…) and even non-prescribed complementary alternative drugs must have been stopped for at least 30 days before the study. All subjects were instructed to use non-hormonal, double-barrier contraception such as a condom or diaphragm, each combined with a spermicide.

Interventions

Eligible subjects were randomized into placebo and treatment groups based on the computer-generated list. All participants received a dose of 280 mg silymarin including two tablets of Livergol 140 mg, Goldaru Pharma Co. Isfahan-Iran) or placebo (Goldaru Pharma Co. Isfahan-Iran) daily in two meals (after breakfast and dinner) for 12 weeks along with standard treatment of endometrioma (dienogest 2 mg/day). There is evidence that medical treatment, in particular with progestogens, is effective in reducing pain symptoms and size of endometrioma lesions23. In the category of progestogens, dienogest is a fourth-generation selective progestin with a substantial local effect on endometriotic lesions in women have been taking dienogest 2 mg daily for at least six months24,25. Therefore, all of the participants had taken dienogest for at least 6 months. This dosage was chosen because it is safe and effective in treating liver diseases26. The therapeutic doses of silymarin have been considered safe and well-tolerated in humans and it has low risks of drug interactions27. Some slight gastrointestinal discomforts like nausea and diarrhea might be accrued28, however, participants did not report any side effects related to silymarin.

Randomization and blinding

Simple randomization was done according to a computer-generated list of random number groups prepared using Statistical Analysis System Software Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All participants were randomly allocated to each arm and given the tablets based on a computer-generated randomization list by the investigator. Treatment and placebo allocations were blinded to subjects, the investigator, and the attending doctor.

Trial procedures and assessments

At the first and follow-up visit that was planned after 12-week treatment, participants were referred to the lab and sonography single-center (based on routine standard protocols) to measure the concentration of IL-6 in serum by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) using ELISA kit provided by Siemens (Berlin and Munich, Germany, pg/mL) and the sensitivity of the IL 6 assay was 0.038 pg/mL and inter and intra-assay coefficients of variation were less than 9.8 and 6.6%, respectively. Recording of the sizes of the endometrioma lesions via three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasonography (by the same physician in blind), respectively. In addition, they were asked to fill out several self-report questionnaires as follows:

Firstly, demographic data that consists of address, phone number, date of birth, weight, height, Body Mass Index (BMI), education level, occupation, education level of husband, and a history of the disease was gathered.

Because the observation suggests that IL-6 may be a good marker of disease prediction and progression and may serve as biomarkers for the diagnosis of endometriosis29–31.

Female sexual function (FSFI)

FSFI investigates the sexual function and consists of 19 Likert-scale questions in six domains of desire, arousal, lubrication, satisfaction, orgasm, and pain. The lower score is, the more sexual function impaired32. The Iranian version of FSFI has been evaluated for both reliability and validity33.

Short form health survey (SF-12)

SF-12 is designed to evaluate the physical and mental components of health-related QoL by 12 questions. Lower scores indicate inferior health-related QoL34. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire have been confirmed in Iran35.

Visual analog scale (VAS)

VAS has been used most often to assess the intensity of endometriosis-related pain (dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, and menstrual and non-menstrual dysphasia). It is an 11-point scale in which 0 represented the absence of pain, while 10 meant unbearable pain36.

Outcome

One of the primary endpoints was a significant reduction in the mean pelvic pain assessed after 12-week treatment on a VAS. Other primary efficacy endpoints at weeks 12 included a significant decrease in the volume of endometrioma lesions diagnosed via transvaginal ultra-sonography and any change from baseline in the level of IL-6.

Secondary efficacy endpoints were improvement of individuals’ QoL and sexual function assessed on mentioned questionnaires.

Statistical analysis

Based on the study results of Almassinokiani et al.37, who assessed the effects of vitamin D on endometriosis-associated pain, with a 99% confidence interval and 90% power of the test, the sample size was determined as 35 individuals for each group. By counting 20% sample loss, the minimum sample size was estimated at 40 individuals in each group, meaning that 80 women diagnosed with endometrioma who had the inclusion criteria (40 persons in each group) were recruited for the present study.

where, α is the probability of type I errors (α = 0.05), and βindicates the probability of type II errors (β = 0.20). In addition, ( − )/σ represents the size effect observed that is equal 0.7.

All statistical analyses were performed by the SPSS software (ver. 22.0) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The data of normality in distribution were examined by one sample K-S. Group comparisons were carried out with Student’s t-test and Chi-square test, and Paired T-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares university (code: IR.MODARES.REC.1398.143). All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Regional Research Committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments. After explaining the study's purposes, informed written consent and verbal assent were obtained from all participants. They were informed that their participation was voluntary, confidential and anonymous, and that they had the right to withdraw from the research at any time.

Results

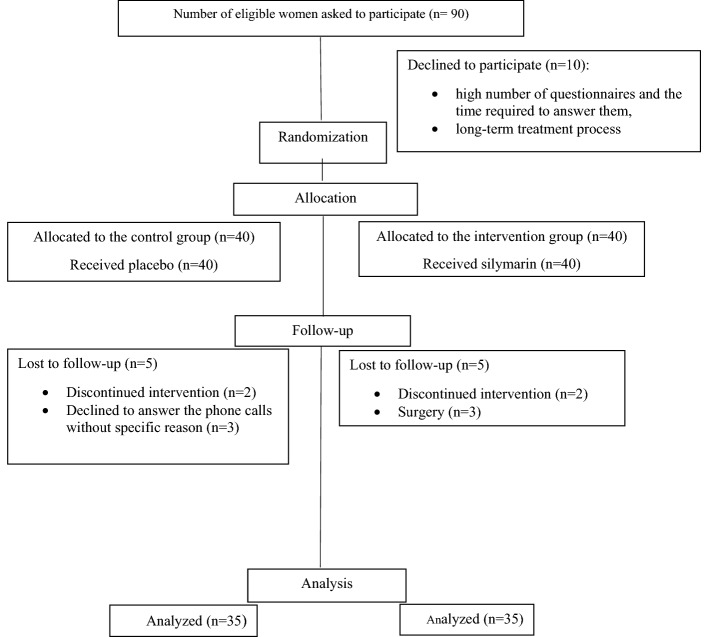

Overall, 10 out of the 90 potentially eligible women refused to participate in the study because of time consuming completing of questionnaires and longtime treatment process, so the response rate was approximately 88%. A total of 80 individuals, (40 women in each group) were enrolled into the study, 10 were excluded due to the unwillingness to peruse recommended treatment (n = 8), surgery (n = 3), the rate of sample loss was 12% (Fig. 1). Finally, 35 women were enrolled in each group.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants: women screened for eligibility, admitted to and randomized in the study on the use of the silymarin .

Patients reported a mean of 3.4 years since the first diagnosis of endometriosis. Table 1 describes the characteristics of women in the intervention and control groups (the minimum age of participants was 21 years old). There was no statistically significant difference in women’s age, Body Mass Index (BMI), parity, educational level, and occupation status between the two groups (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics between intervention and control groups.

| Variable | Intervention group n = 35 |

Control group n = 35 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of female* | 36.49 ± 8.11 | 33.94 ± 7.00 | 0.16 |

| Number of children** | |||

| 0 | 11 (31.4) | 18 (51.4) | 0.29 |

| 1 | 13 (37.1) | 9 (25.7) | |

| 2 | 10 (28.6) | 6 (17.1) | |

| 3 and more | 1 (2.9) | 2 (5.7) | |

| Education of female** | |||

| Undergraduate | 17 (48.6) | 14 (40.0) | 0.47 |

| Postgraduate | 18 (51.4) | 21 (60.0) | |

| Occupation** | |||

| Housewife | 19 (54.3) | 22 (62.9) | 0.46 |

| Employee | 16 (45.7) | 13 (37.1) | |

| BMI (kg/ m2) * | 24.25 ± 4.02 | 24.54 ± 4.02 | 0.75 |

BMI Body Mass Index.

*Values are given as mean ± SD using t-test.

**Values are given as a number (%) using Chi-squared test.

As can be seen in Table 2, evaluation of the two groups with regard to FSFI before and after treatment did not show any significant differences. The total score of FSFI was significantly lower in control group after treatment (25.54 ± 2.74 vs 24.64 ± 2.74, P = 0.03).

Table 2.

Comparison of FSFI scores between intervention and control groups.

| Variable | Intervention group n = 35 Mean ± SD |

Control group n = 35 Mean ± SD |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desire | |||

| Pre-assessment | 3.58 ± 0.71 | 3.45 ± 0.66 | 0.42 |

| Post-assessment | 3.90 ± 0.75 | 3.50 ± 0.82 | 0.06 |

| P-value** | 0.01 | 0.72 | |

| Arousal | |||

| Pre-assessment | 3.86 ± 1.18 | 4.01 ± 0.78 | 0.56 |

| Post-assessment | 4.21 ± 1.01 | 3.85 ± 0.78 | 0.15 |

| P-value** | 0.40 | 0.23 | |

| Lubrication | |||

| Pre-assessment | 4.37 ± 1.22 | 4.87 ± 0.97 | 0.87 |

| Post-assessment | 4.53 ± 1.04 | 4.69 ± 0.83 | 0.54 |

| P-value** | 0.44 | 0.29 | |

| Orgasm | |||

| Pre-assessment | 4.43 ± 1.25 | 4.68 ± 0.81 | 0.37 |

| Post-assessment | 4.45 ± 1.25 | 4.15 ± 0.91 | 0.31 |

| P-value** | 0.40 | 0.01 | |

| Satisfaction | |||

| Pre-assessment | 4.50 ± 1.23 | 4.61 ± 0.88 | 0.90 |

| Post-assessment | 4.40 ± 1.04 | 4.36 ± 0.90 | 0.69 |

| P-value** | 0.54 | 0.06 | |

| Pain | |||

| Pre-assessment | 3.73 ± 1.23 | 3.94 ± 1.35 | 0.44 |

| Post-assessment | 4.07 ± 0.76 | 4.05 ± 0.79 | 0.97 |

| P-value** | 0.18 | 0.50 | |

| Total score | |||

| Pre-assessment | 24.39 ± 4.66 | 25.54 ± 2.74 | 0.25 |

| Post-assessment | 25.76 ± 4.33 | 24.64 ± 2.74 | 0.27 |

| P-value** | 0.28 | 0.03 | |

FSFI Female Sexual Function Index.

*T-test was carried out for comparison of the groups.

**Paired T-test was carried out for comparison of changes between the groups.

The comparison of SF-12 scores between the intervention and control groups is shown in Table 3. The mean total scores of SF-12 were not significantly different between groups before treatment compared with after intervention (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Comparison of the scores of subgroups of QoL between intervention and control groups.

| Variable | Intervention group n = 35 Mean ± SD |

Control group n = 35 Mean ± SD |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sum score of physical components (PCS-12) | |||

| Pre-assessment | 76.23 ± 13.59 | 72.03 ± 18.95 | 0.31 |

| Post-assessment | 78.25 ± 11.51 | 71.45 ± 20.52 | 0.13 |

| P-value** | 0.91 | 0.71 | |

| Sum score of mental components (MCS-12) | |||

| Pre-assessment | 69.79 ± 14.50 | 70.72 ± 13.80 | 0.79 |

| Post-assessment | 73.20 ± 14.33 | 72.43 ± 12.20 | 0.83 |

| P-value** | 0.47 | 0.36 | |

| Total score | |||

| Pre-assessment | 73.01 ± 11.73 | 71.51 ± 14.34 | 0.65 |

| Post-assessment | 75.73 ± 11.56 | 72.19 ± 15.35 | 0.34 |

| P-value** | 0.58 | 0.37 | |

QoL Quality of Life.

*T-test was carried out for comparison of the groups.

**Paired T-test was carried out for comparison of changes between the group.

It can be seen from the data in Tables 4 and 5 that there was significant difference in intervention group for the pelvic pain mean changes from baseline to treatment end (7.29 ± 2.49 vs 4.88 ± 2.00, P < 0.001). In addition, IL-6 levels decreased significantly during the 90-day study period (2.40 ± 0.52 vs 2.12 ± 0.20, P = 0.002).

Table 4.

Comparison of the serum levels of IL-6 (pg/mL) between intervention and control groups.

| Variable | Intervention group n = 35 Mean ± SD |

Control group n = 35 Mean ± SD |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | |||

| Pre-assessment | 2.40 ± 0.52 | 2.57 ± 0.78 | 0.29 |

| Post-assessment | 2.12 ± 0.20 | 2.42 ± 0.73 | 0.03 |

| P-value** | 0.002 | 0.30 | |

IL-6: Interleukin 6, pg/mL (picograms per milliliter).

*T-test was carried out for comparison of the groups.

**Paired T-test was carried out for comparison of changes between the groups.

Table 5.

Comparison of the Visual Analog Pain Scale between intervention and control groups.

| Variable | Intervention group n = 35 Mean ± SD |

Control group n = 35 Mean ± SD |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pelvic pain (VAS) | |||

| Pre-assessment | 7.29 ± 2.49 | 6.73 ± 2.97 | 0.41 |

| Post-assessment | 4.88 ± 2.00 | 6.61 ± 2.64 | 0.01 |

| P-value** | < 0.001 | 0.64 | |

*T-test was carried out for comparison of the groups.

**Paired T-test was carried out for comparison of changes between the groups.

Table 6 shows a comparison between the 2 groups for the endometrioma lesions volumes at before and after treatment. There were significant differences between the volumes of endometrioma lesions in right ovary intervention group.

Table 6.

Comparison of the ovaries’ volume between intervention and control groups.

| Variable | Intervention group n = 35 Mean ± SD |

Control group n = 35 Mean ± SD |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right ovary | |||

| Pre-assessment | 58,863.51 ± 83,820.56 | 75,848.03 ± 135,023.70 | 0.59 |

| Post-assessment | 33,694.85 ± 53,124.60 | 81,963.81 ± 150,300.15 | 0.24 |

| P-value** | 0.04 | 0.16 | |

| Left ovary | |||

| Pre-assessment | 65,773.67 ± 76,725.35 | 54,857.73 ± 57,983.99 | 0.60 |

| Post-assessment | 58,079.16 ± 73,622.66 | 70,801.58 ± 93,146.68 | 0.66 |

| P-value** | 0.23 | 0.26 | |

*T-test was carried out for comparison of the groups.

**Paired T-test was carried out for comparison of changes between the groups.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first double-blind, randomized clinical trial conducted to investigate the effect of silymarin on serum IL‐6 Levels, the size of endometrioma lesions, QoL, pain, and sexual function in women diagnosed with OMA.

This study confirms that silymarin can be effective in reducing the size of endometrioma lesions is consistent with previous observations in animal models. Jouhari et al. compared the effects of silymarin, Cabergoline, and Letrozole on induced endometrial lesions in rats for about 6 months. Silymarin, Letrozole, and Cabergoline administration could decrease size and histopathologic grade of the induced endometrial lesions significantly and those who were received silymarin had significantly higher serum total antioxidant activity compared to control after 21 days18.

Nahari et al. evaluating legions establishment and growth in experimentally-induced endometriosis in 12 rats after 28 days of oral administration of silymarin showed that the combination of enhancing ERK1/2 expression and suppressing the Bcl-2 expression by silymarin accompanying with down-regulating the angiogenesis ratio led to promote the apoptosis pathway, consequently induced severe fibrosis in endometriotic-like legions19.

A recent prospective study showed that not only could silibinin induce OS and lipid peroxidation in human endometriotic cells, but also it exerted antiproliferative and apoptotic impacts on human endometriotic cell lines VK2/E6E7 and End1/E6E720. Moreover, the effects of silibinin on reducing endometriotic lesions by inhibiting the expression of inflammatory cytokines was verified by using an animal model mimicking the retrograde menstruation hypothesis in mice and they proved the possibility of effectiveness of silibinin as a novel therapeutic agent or supplement in inhibiting progression of endometriosis in vitro and in vivo20.

The results also showed that oral administration of silymarin 280 mg/day decreased the IL-6 concentration levels significantly during the study period within the intervention group. Arafa Keshk et al. evaluating the potential protective effects of silymarin against indomethacin-induced gastric injury in rats, have demonstrated that suppression in gastric inflammation by decreasing myeloperoxidase activity, TNF- α, and IL-6 expression levels along with NF-κB expression. Meanwhile, silymarin prevent gastric OS via inhibition of lipid peroxides formation, enhancement of glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase activities and up-regulation of Nuclear Factor-Erythroid-2-Related Factor 2 (Nrf2), the redox-sensitive master regulator of OS signaling38.

Additionally, Wei Zhang et al. showed that silymarin could protect against the liver injury caused by ethanol administration as it markedly downregulated the expression of NF-κB p65, ICAM-1 and IL-6 in liver tissue39.

Rongjuan Zheng et al. evaluated the chemo-preventive effect of silibinin (major component of silymarin) on a Colitis-Associated Cancer (CAC) mouse model and determined its impact on IL-6/STAT3 signaling. Silibinin decreased the amount and size of tumors in mice accompanying with inhibition of colonic tumor cell proliferation and promotion of cellular apoptosis. Furthermore, they showed that silibinin could reduce the production of inflammatory cytokines and can protect against colitis-associated tumorigenesis in mice via inhibiting IL-6/STAT340.

In addition, it is revealed that silymarin attenuate the expression of NF-kB and the subsequent inflammatory cascade by suppressing IκB, effectively can down-regulate the expressions of TPA-induced IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and COX-2 in a dose-dependent manner41,42.

Numerous mechanisms are involved in endometriosis-related pain such as various algogens (pain-producing agents), cytokines (such as IL-1b, IL-6, and TNF-a), growth factors (such as b-nerve growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor), and several chemokines, such as CCL243,44.

Several papers have investigated that different kind of antioxidant such as vitamin E and vitamin C can reduce peritoneal inflammatory markers and decrease chronic pelvic pain in endometriosis women45–47. It might be speculated silymarin could be effective in reducing pain as an antioxidant agent which is at least ten times more potent than vitamin E can suppress nitric oxide, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), leukotrienes, cytokines production, and neutrophils infiltration48–50. This study supports evidence from previous observations about the analgesic effects of silymarin.

The exact physiopathology of endometriosis is poorly understood. Inflammation, however, is known as a main factor in initiation and progression of endometriosis. Hence, inflammatory mediators such as IL‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐8 increase in the peritoneal, serum, and endometrium of endometriosis patients, leading to enhancing proliferation and decreasing apoptotic rate in endometriotic cells51,52. In addition, the expression of NF-κB, Cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2), Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), IL‐6, TNF‐α, IL‐8, C‐C Motif Chemokine 2 (MCP‐1), and IL‐10 have increased in endometriosis cases53,54. An inflammatory response is induced by cytokines and prostaglandins, which produce inflammation at the site of endometriotic implantation55. Following this inflammatory response, new vascularization and new fibrous tissue formation are initiated55. This causes adhesions and pain associated with this disease process as a result of the snowball effect. Moreover, these issues also contribute to the most common complications of this disease, such as infertility and chronic pelvic pain. In comparison with patients with stage one or two endometriosis, patients with endometriomas usually suffer from a more severe disease state and experience this to a greater extent56.

The anti-inflammatory effects of silymarin is mediated through the inhibition of NF-κB regulated gene products including COX-2 and Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), as well as inflammatory cytokines57, through suppressing the degradation of Inhibitory kappa B (IκB) degradation, preventing both the translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus and the activation of gene transcription associated with inflammation58.

Oxidative Stress, an imbalance between ROS and antioxidants, is known as a main factor in the endometriosis pathogenesis59. Also, increased peritoneal oxidized low-density lipoprotein levels and ROS production by macrophages are observed in association with an altered expression of endometrial antioxidant and pro-oxidant enzymes59. In addition, Compared to healthy women, endometriotic cells increase the expression of glutathione peroxidase and Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) activity, while catalase concentrations are lower60. By eliciting c-Fos and c-Jun expression, OS activates the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK)/Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK) pathway and promotes the survival and proliferation of endometriotic lesions. Proliferative responses are influenced by the ERK signaling pathway through the production of endogenous ROS61. Moreover, the activity of antioxidant system is less in endometriosis patients than healthy subjects62. Endometriosis subjects exhibit elevated growth, proinflammatory, and angiogenic mediators, as a result of ROS generation produced in peritoneal macrophages by iron overload63.

Silymarin is considered as an antioxidant agent via several mechanisms that include scavenging free radicals and chelating metals-promoters such as Fe and Cu, preventing ROS formation enzymes e.g. NAPDH Oxidases, activates antioxidant enzymes and inhibiting of lipid peroxidation, regulating the cell membrane permeability and increasing the stability, increases ribosomal protein synthesis by stimulation RNA polymerase, and regulation of signaling through activation of Nrf2 and inhibition of NF-κB64.

According to the fact that endometriosis is a very complex condition with wide range of clinical features including pelvic pain, dyspareunia, infertility, and menstrual irregularities that might compromise QoL, psychological wellbeing, sexual function, and interpersonal relationships of affected women65,66, Caruso et al. evaluated the effects of dienogest on QoL and sexual function in endometriosis women, reported that progressive reduction of the pain could contribute in improving the QoL and sexual life67.

Very little was found in the literature on the question of the effectiveness of silymarin on QoL and sexual function. Gillessen et al. investigating the effect of silymarin on liver function and QoL in a non-interventional study, reported that improvement in liver-related symptoms and increased QoL after 2 months68.

Previous researches had proved that silymarin and other anti-oxidants agents can enhance QoL in patients because of their positive effects on pain reduction69,70. However, the present study found inconsistent results and there was neither a significant difference in SF-12 between treatment and placebo groups nor within groups pre/post treatment.

The strengths of the study are the RCT design and novelty. In addition, as maintaining endometriosis associated women on a placebo is unethical, the intervention was recommended along with routine treatment. However, the principal limitation of the study is the 8% loss to follow-up and the short duration of follow-up; therefore, results probably should be extrapolated by long-term follow up. Additionally, these data warrant further investigations for the potential use of silymarin in the management of endometriosis features to assess long-term effects of this treatment by larger sample. One of the major limitations of this study is poor oral bioavailability of silymarin due to its poor enteral absorption, instability in the gastric environment, and poor solubility. Thus, silymarin must be administered at a higher dose in order to enhance therapeutic efficacy71. According to the promising effects of silymarin on chronic diseases, the use of nanotechnological strategies appears can improve its bioavailability and provide a prolonged silymarin release at the site of absorption72.

Conclusion

In conclusion, silymarin can be considered as a feasible option for treatment women with endometrioma-associated symptoms that has few side effects.

Acknowledgements

This study was carried out with the kind collaboration of the participants. We would also like to appreciate the staff of the Tarbiat Modares University and the participating health care centers for their valuable contributions.

Abbreviations

- IL

Interleukin

- QoL

Quality of Life

- COX‐2

Cyclooxygenase‐2

- MCP‐1

C‐C Motif Chemokine 2 (MCP‐1)

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- IκB

Inhibitory kappa B

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- TNF‐α

Tumor necrosis factor‐α

- MCP‐2

C–C motif chemokine 2

- OMA

Ovarian endometrioma

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- OCPs

Oral contraceptive pills

- GnRH-a

Releasing hormone analogues

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa B p65

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor-erythroid-2-related factor 2

- CAC

Colitis-associated cancer

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- pg/mL

Picograms per milliliter

- FSFI

Female sexual function

- SF-12

Short form health survey

- VAS

Visual analog scale

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Author contributions

N.M and Sh.JS contributed to the conception and design of the study; N.M did the literature search; N.M, and M.N performed the statistical analysis; M.N, N.M, Sh.JS, and S.R, wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, and read and approved the submitted version.

Data availability

The data sets used and analyzed for the current study are available upon reasonable request of the corresponding author Dr. Shahideh Jahanian (shahideh.jahanian@modares.ac.ir).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Greene AD, Lang SA, Kendziorski JA, Sroga-Rios JM, Herzog TJ, Burns KA. Endometriosis: Where are we and where are we going? Reproduction. 2016;152(3):R63. doi: 10.1530/REP-16-0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashrafi M, Sadatmahalleh SJ, Akhoond MR, Talebi M. Evaluation of risk factors associated with endometriosis in infertile women. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2016;10(1):11–21. doi: 10.22074/ijfs.2016.4763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giudice LC. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362(25):2389–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culley L, Law C, Hudson N, Denny E, Mitchell H, Baumgarten M, et al. The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women's lives: A critical narrative review. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2013;19(6):625–639. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soliman AM, Surrey ES, Bonafede M, Nelson JK, Vora JB, Agarwal SK. Health care utilization and costs associated with endometriosis among women with medicaid insurance. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2019;25(5):566–572. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.5.566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozkan S, Arici A. Advances in treatment options of endometriosis. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2009;67(2):81–91. doi: 10.1159/000163071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez AM, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Panina-Bordignon P, Vercellini P, Candiani M. The distinguishing cellular and molecular features of the endometriotic ovarian cyst: From pathophysiology to the potential endometrioma-mediated damage to the ovary. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2014;20(2):217–230. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velasco I, Acién P, Campos A, Acién MI, Ruiz-Maciá E. Interleukin-6 and other soluble factors in peritoneal fluid and endometriomas and their relation to pain and aromatase expression. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2010;84(2):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vercellini P, Crosignani P, Somigliana E, Viganò P, Buggio L, Bolis G, et al. The 'incessant menstruation' hypothesis: A mechanistic ovarian cancer model with implications for prevention. Hum. Reprod. 2011;26(9):2262–2273. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor RN, Hummelshoj L, Stratton P, Vercellini P. Pain and endometriosis: Etiology, impact, and therapeutics. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2012;17(4):221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.mefs.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pradhan SC, Girish C. Hepatoprotective herbal drug, silymarin from experimental pharmacology to clinical medicine. Indian J. Med. Res. 2006;124(5):491–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trappoliere M, Caligiuri A, Schmid M, Bertolani C, Failli P, Vizzutti F, et al. Silybin, a component of sylimarin, exerts anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrogenic effects on human hepatic stellate cells. J. Hepatol. 2009;50(6):1102–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saliou C, Valacchi G, Rimbach G. Assessing bioflavonoids as regulators of NF-kappa B activity and inflammatory gene expression in mammalian cells. Methods Enzymol. 2001;335:380–387. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(01)35260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaggi AS, Singh N. Drug Discovery from Mother Nature. Springer; 2016. Silymarin and its role in chronic diseases; pp. 25–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayer K, Myers R, Lee S. Silymarin treatment of viral hepatitis: A systematic review. J. Viral Hepatitis. 2005;12(6):559–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vargas-Mendoza N, Madrigal-Santillán E, Morales-González Á, Esquivel-Soto J, Esquivel-Chirino C, González-Rubio MG-L, et al. Hepatoprotective effect of silymarin. World J. Hepatol. 2014;6(3):144. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i3.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixit N, Baboota S, Kohli K, Ahmad S, Ali J. Silymarin: A review of pharmacological aspects and bioavailability enhancement approaches. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2007;39(4):172. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.36534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jouhari S, Mohammadzadeh A, Soltanghoraee H, Mohammadi Z, Khazali S, Mirzadegan E, et al. Effects of silymarin, cabergoline and letrozole on rat model of endometriosis. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018;57(6):830–835. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nahari E, Razi M. Silymarin amplifies apoptosis in ectopic endometrial tissue in rats with endometriosis; implication on growth factor GDNF, ERK1/2 and Bcl-6b expression. Acta Histochem. 2018;120(8):757–767. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ham J, Kim J, Bazer FW, Lim W, Song G. Silibinin-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction suppress growth of endometriotic lesions. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234(4):4327–4341. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehdizadeh Kashi A, Niakan G, Ebrahimpour M, Allahqoli L, Hassanlouei B, Gitas G, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the comparative effects of dienogest and the combined oral contraceptive pill in women with endometriosis. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022;156(1):124–132. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Holsbeke C, Van Calster B, Guerriero S, Savelli L, Paladini D, Lissoni AA, et al. Endometriomas: Their ultrasound characteristics. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;35(6):730–740. doi: 10.1002/uog.7668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunselman G, Vermeulen N, Becker C, Calhaz-Jorge C, D'Hooghe T, De Bie B, et al. ESHRE guideline: Management of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014;29(3):400–412. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Köhler G, Faustmann TA, Gerlinger C, Seitz C, Mueck AO. A dose-ranging study to determine the efficacy and safety of 1, 2, and 4 mg of dienogest daily for endometriosis. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2010;108(1):21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Momoeda M, Harada T, Terakawa N, Aso T, Fukunaga M, Hagino H, et al. Long-term use of dienogest for the treatment of endometriosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2009;35(6):1069–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2009.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abenavoli L, Capasso R, Milic N, Capasso F. Milk thistle in liver diseases: Past, present, future. Phytother. Res. 2010;24(10):1423–1432. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tighe SP, Akhtar D, Iqbal U, Ahmed A. Chronic liver disease and silymarin: A biochemical and clinical review. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2020;8(4):454. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2020.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soleimani V, Delghandi PS, Moallem SA, Karimi G. Safety and toxicity of silymarin, the major constituent of milk thistle extract: An updated review. Phytother. Res. 2019;33(6):1627–1638. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malutan AM, Drugan T, Costin N, Ciortea R, Bucuri C, Rada MP, et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokines for evaluation of inflammatory status in endometriosis. Central-Eur. J. Immunol. 2015;40(1):96. doi: 10.5114/ceji.2015.50840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang J, Jiang Z, Xue M. Serum and peritoneal fluid levels of interleukin-6 and interleukin-37 as biomarkers for endometriosis. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2019;35(7):571–575. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2018.1554034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kokot I, Piwowar A, Jędryka M, Sołkiewicz K, Kratz EM. Diagnostic significance of selected serum inflammatory markers in women with advanced endometriosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(5):2295. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosen CB, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, Dgostino R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohammadi K, Heydari M, Faghihzadeh S. The female sexual function index (FSFI): Validation of the Iranian version. Sci. Inf. Data. 2008;7:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Mousavi SJ, Omidvari S. The Iranian version of 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12): Factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerlinger C, Schumacher U, Faustmann T, Colligs A, Schmitz H, Seitz C. Defining a minimal clinically important difference for endometriosis-associated pelvic pain measured on a visual analog scale: Analyses of two placebo-controlled, randomized trials. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Almassinokiani F, Khodaverdi S, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Akbari P, Pazouki A. Effects of vitamin D on endometriosis-related pain: A double-blind clinical trial. Med. Sci. Monit. 2016;22:4960–4966. doi: 10.12659/MSM.901838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arafa Keshk W, Zahran SM, Katary MA, Abd-Elaziz AD. Modulatory effect of silymarin on nuclear factor-erythroid-2-related factor 2 regulated redox status, nuclear factor-κB mediated inflammation and apoptosis in experimental gastric ulcer. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017;273:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang W, Hong R, Tian T. Silymarin's protective effects and possible mechanisms on alcoholic fatty liver for rats. Biomol. Ther. 2013;21(4):264–269. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2013.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng R, Ma J, Wang D, Dong W, Wang S, Liu T, et al. Chemopreventive effects of silibinin on colitis-associated tumorigenesis by inhibiting IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018;2018:1562010. doi: 10.1155/2018/1562010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atawia RT, Mosli HH, Tadros MG, Khalifa AE, Mosli HA, Abdel-Naim AB. Modulatory effect of silymarin on inflammatory mediators in experimentally induced benign prostatic hyperplasia: Emphasis on PTEN, HIF-1α, and NF-κB. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2014;387(12):1131–1140. doi: 10.1007/s00210-014-1040-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu W, Li Y, Zheng X, Zhang K, Du Z. Potent inhibitory effect of silibinin from milk thistle on skin inflammation stimuli by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Food Funct. 2015;6(12):3712–3719. doi: 10.1039/C5FO00899A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rocha MG, e Silva JC, Ribeiro da Silva A, Candido Dos Reis FJ, Nogueira AA, Poli-Neto OB. TRPV1 expression on peritoneal endometriosis foci is associated with chronic pelvic pain. Reprod. Sci. 2011;18(6):511–5. doi: 10.1177/1933719110391279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKinnon BD, Bertschi D, Bersinger NA, Mueller MD. Inflammation and nerve fiber interaction in endometriotic pain. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;26(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amini L, Chekini R, Nateghi MR, Haghani H, Jamialahmadi T, Sathyapalan T, et al. the effect of combined vitamin C and vitamin E supplementation on oxidative stress markers in women with endometriosis: A randomized, triple-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Pain Res. Manage. 2021;2021:5529741. doi: 10.1155/2021/5529741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.East-Powell M, Reid R. Medical synopsis: Antioxidant supplementation may support reduction in pelvic pain in endometriosis. Adv. Integr. Med. 2019;6(4):181–182. doi: 10.1016/j.aimed.2019.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lete I, Mendoza N, de la Viuda E, Carmona F. Effectiveness of an antioxidant preparation with N-acetyl cysteine, alpha lipoic acid and bromelain in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain: LEAP study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018;228:221–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gupta OP, Sing S, Bani S, Sharma N, Malhotra S, Gupta BD, et al. Anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic activities of silymarin acting through inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(1):21–24. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(00)80017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kang JS, Jeon YJ, Park SK, Yang KH, Kim HM. Protection against lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis and inhibition of interleukin-1beta and prostaglandin E2 synthesis by silymarin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;67(1):175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ajay K. Polyphenolic compounds with biological and pharmacological activity. Herbs Spices Med. Plants. 1986 doi: 10.2174/1200101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bersinger NA, Günthert AR, McKinnon B, Johann S, Mueller MD. Dose-response effect of interleukin (IL)-1β, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interferon-γ on the in vitro production of epithelial neutrophil activating peptide-78 (ENA-78), IL-8, and IL-6 by human endometrial stromal cells. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011;283(6):1291–1296. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vetvicka V, Laganà AS, Salmeri FM, Triolo O, Palmara VI, Vitale SG, et al. Regulation of apoptotic pathways during endometriosis: From the molecular basis to the future perspectives. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016;294(5):897–904. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sikora J, Smycz-Kubańska M, Mielczarek-Palacz A, Kondera-Anasz Z. Abnormal peritoneal regulation of chemokine activation-The role of IL-8 in pathogenesis of endometriosis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2017;77(4):12622. doi: 10.1111/aji.12622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sikora J, Mielczarek-Palacz A, Kondera-Anasz Z. Association of the precursor of interleukin-1β and peritoneal inflammation-role in pathogenesis of endometriosis. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2016;30(6):831–837. doi: 10.1002/jcla.21944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schliep KC, Chen Z, Stanford JB, Xie Y, Mumford SL, Hammoud AO, et al. Endometriosis diagnosis and staging by operating surgeon and expert review using multiple diagnostic tools: An inter-rater agreement study. BJOG. 2017;124(2):220–229. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoyle AT, Puckett Y. Endometrioma. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim EJ, Kim J, Lee MY, Sudhanva MS, Devakumar S, Jeon YJ. Silymarin inhibits cytokine-stimulated pancreatic beta cells by blocking the ERK1/2 pathway. Biomol. Ther. 2014;22(4):282. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2014.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin W-W, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2007;117(5):1175–1183. doi: 10.1172/JCI31537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Augoulea A, Mastorakos G, Lambrinoudaki I, Christodoulakos G, Creatsas G. The role of the oxidative-stress in the endometriosis-related infertility. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2009;25(2):75–81. doi: 10.1080/09513590802485012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Öner-İyidoğan Y, Koçak H, Gürdöl F, Korkmaz D, Buyru F. Indices of oxidative stress in eutopic and ectopic endometria of women with endometriosis. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2004;57(4):214–217. doi: 10.1159/000076691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tosti C, Pinzauti S, Santulli P, Chapron C, Petraglia F. Pathogenetic mechanisms of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 2015;22(9):1053–1059. doi: 10.1177/1933719115592713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prieto L, Quesada JF, Cambero O, Pacheco A, Pellicer A, Codoceo R, et al. Analysis of follicular fluid and serum markers of oxidative stress in women with infertility related to endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2012;98(1):126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lousse J-C, Van Langendonckt A, Defrere S, Ramos RG, Colette S, Donnez J. Peritoneal endometriosis is an inflammatory disease. Front. Bioscie. Elite. 2012;4(1):23–40. doi: 10.2741/e358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taleb A, Ahmad KA, Ihsan AU, Qu J, Lin N, Hezam K, et al. Antioxidant effects and mechanism of silymarin in oxidative stress induced cardiovascular diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;102:689–698. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Friedl F, Riedl D, Fessler S, Wildt L, Walter M, Richter R, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life, anxiety, and depression: An Austrian perspective. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015;292(6):1393–1399. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.La Rosa VL, De Franciscis P, Barra F, Schiattarella A, Tropea A, Tesarik J, et al. Sexuality in women with endometriosis: A critical narrative review. Minerva Med. 2020;111(1):79–89. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4806.19.06299-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Caruso S, Iraci M, Cianci S, Casella E, Fava V, Cianci A. Quality of life and sexual function of women affected by endometriosis-associated pelvic pain when treated with dienogest. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2015;38(11):1211–1218. doi: 10.1007/s40618-015-0383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gillessen A, Herrmann WA, Kemper M, Morath H, Mann K. Effect of silymarin on liver health and quality of life. Results of a non-interventional study. MMW Fortschr. Med. 2014;156(Suppl 4):120–126. doi: 10.1007/s15006-014-3758-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fried MW, Navarro VJ, Afdhal N, Belle SH, Wahed AS, Hawke RL, et al. Effect of silymarin (milk thistle) on liver disease in patients with chronic hepatitis C unsuccessfully treated with interferon therapy: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;308(3):274–282. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.8265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Salmond SJ, George J, Strasser S, Byth K, Rawlinson B, Mori T, et al. Hep573 study: A randomised, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial of silymarin alone and combined with antioxidants to improve liver function and quality of life in people with chronic hepatitis C. Aust. J. Herb. Naturop. Med. 2019;31(2):64–76. doi: 10.33235//ajhnm.31.2.64-76. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bijak M. Silybin, a major bioactive component of milk thistle (Silybum marianum L. Gaernt.): Chemistry, bioavailability, and metabolism. Molecules. 2017;22(11):1942. doi: 10.3390/molecules22111942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di Costanzo A, Angelico R. Formulation strategies for enhancing the bioavailability of silymarin: The state of the art. Molecules. 2019;24(11):2155. doi: 10.3390/molecules24112155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analyzed for the current study are available upon reasonable request of the corresponding author Dr. Shahideh Jahanian (shahideh.jahanian@modares.ac.ir).