Abstract

A technique was developed with flow cytometry to quantify the two immediate-early proteins ZEBRA and Rta, which are involved in the activation of Epstein-Barr virus replication. We evaluated four monoclonal antibodies on four cell lines (B95-8, RAJI, Namalwa, and P3HR1) with varying levels of expression of these replication-phase antigens. The Namalwa lymphoma cell line was used as a negative control. Four fixation-permeabilization procedures were compared. The preparation of cells with paraformaldehyde and methanol in sequence, and antigen detection with AZ125 and AR 5A9 monoclonal antibodies, were found to be the optimal conditions in these cell lines. Our procedure allowed ZEBRA antigen to be detected in 4.85% of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from a transplant recipient with a lymphoproliferative disease.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is the causative agent of infectious mononucleosis and is associated with several malignancies (including Burkitt's lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and immunoblastic lymphomas) in transplant recipients and patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (28). EBV infects normal resting B cells in vitro and activates them in a way reminiscent of that in which B cells are activated in response to their cognate antigen. The resulting immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) express a well-defined phenotype characterized by the expression of high levels of activation and adhesion molecules and resemble lymphoblasts (22). The virus achieves this by encoding six EBNAs, three latent membrane proteins (LMPs), and two untranslated RNAs (EBERs), not all of which are essential for immortalization. EBV remains latent in resting circulating B cells with its genome present in a limited number of copies as covalently closed episomes. The switch between latency and replication of EBV is mediated by the BZLF1 gene in the BamHIZ fragment of EBV. The BZLF1-encoded protein (ZEBRA) is a 38-kDa nuclear protein. Like ZEBRA (or Zta), the R transactivator (Rta) plays an important role in the switch from latency to the lytic phase (16). In both epithelial cells and B lymphocytes (21), Rta alone is capable of disrupting latency. In other cell types, a combination of ZEBRA and Rta induces the activation of early viral promoters (2). In studies based on serological data, we have demonstrated that high titers of anti-ZEBRA antibodies are to be found both in patients with Hodgkin's disease (6, 11) and before posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders in renal transplant recipients (5).

The presence of these two immediate-early proteins in the B-cell lineage, as detected with monoclonal antibodies produced in our laboratory (3), could thus be evaluated as a marker of virus replication, possibly associated with tumor progression (13). Infected cells in the peripheral blood of persistently infected healthy individuals are confined to the B-cell lineage and are present at levels varying between 1 and 50 per 106 B cells (18). In immunocompromised patients, they are present at higher levels, e.g., 1 to 10 lytic-infected cells per 104 B lymphocytes (1, 22), but are rare nevertheless, which makes them difficult to detect with immunofluorescence under light microscopy. The use of flow cytometry seems a promising alternative in this context, as it allows a particular cell population (B lymphocytes) to be first targeted before examining this preselected population for cells expressing lytic-phase antigens.

The goal of our present study was to assess the feasibility of detecting lytic-phase EBV antigens with flow cytometry. To this end, we evaluated different experimental conditions for cell fixation and permeabilization, and several anti-ZEBRA and anti-Rta antibodies, on cell lines expressing lytic-phase EBV antigens. Using the conditions found to be optimal, we then performed some preliminary evaluative tests on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from a transplanted patient with a lymphoproliferative disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures and lytic-phase antigen chemical induction.

Four cell lines that did or did not express lytic-phase EBV antigens were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). The nonpermissive human Burkitt's lymphoma Namalwa cell line (CRL-1432) served as a negative control. The human P3HR-1 (HTB-62) and the marmoset B95-8 lymphoblastoid cell lines are both totally permissive to the virus, leading to its complete replication. The human lymphoblastoid RAJI cell line (CCL-86) leads, after stimulation, to abortive replication (expression of EBV antigens restricted to the immediate-early phase).

All cell lines were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Cergy-Pontoise, France) containing 7.5% (Namalwa), 10% (RAJI and B95-8), or 20% (P3HR-1) fetal calf serum (Life Technologies), 2 mM glutamine (Life Technologies), and a mixture of antibiotics.

Lytic-phase induction or amplification was obtained by adding to the growth medium 50 ng of phorbol 12-myristrate 13-acetate (TPA) (Sigma, Saint-Quentin en Yvelines, France) per ml or a mixture of TPA at the same concentration with 1 mM butyric acid (Sigma). The cells were harvested for fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis 3 days after induction.

MAbs.

Four monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) were obtained by immunizing BALB/c mice with ZEBRA or Rta recombinant antigens, as previously described (3). MAbs AZ125 and AZ130, both from the immunogloblin G2 (IgG2) subclass, were directed against BZLF1 antigens, while AR5A9 and AR8C12, from the IgG1 subclass, recognized BRLF1 antigens. All MAbs were used as ascitic fluid, and AZ125 and AR5A9 underwent additional purification by affinity chromatography on an A protein column (Fast Flow Laboratories) and were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC).

Fixation, permeabilization, and staining of cultured cells.

Four different procedures for fixation and permeabilization, each performed on aliquots of 5 × 105 cells, were evaluated in parallel in the same set of experiments. The techniques for the paraformaldehyde-methanol (PF/M) method and the paraformaldehyde-Tween 20 (PF/T) method followed the procedures previously described (8). Briefly, aliquots were incubated 15 min in 1% paraformaldehyde (Merck, Nogent-sur-Marne, France), washed, and then kept at least 1 h (maximum, 1 month) in 80% methanol at −20°C or incubated overnight at 4°C in 1% paraformaldehyde supplemented with 0.2% Tween 20 (Sigma). The two other methods were commercially available: Intraprep (Immunotech/Coulter, Marseille, France) and Fix&Perm (Caltag/Tebu, Marnes la Coquette, France). Technical procedures were performed according to manufacturer's instructions, with incubations with MAbs performed the same day.

Fixed and permeabilized cells were washed and incubated for various lengths of time (30 to 60 min) at 4 or 37°C with a saturating amount of each anti-EBV MAb or IgG1 or IgG2 isotype control (Caltag/Tebu). MAbs used as ascitic fluid were diluted from 1/1,000 to 1/5,000, whereas purified MAbs and isotype controls were used at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 2 μg per assay. The cells were then washed and, when MAbs were used as ascitic fluid, incubated for 30 min at 4°C with FITC-F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse IgG (Bioatlantique, Nantes, France) diluted at 1/100.

All steps involving incubation were performed in media supplemented with 20% human AB serum to limit nonspecific labeling. Incubation media varied according to the procedure used to prepare the cells: they were, respectively, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for the PF/M method, PBS supplemented with 0.2% Tween 20 for the PF/T method, and the reagents provided in the kit for the two other methods, as specified by the manufacturers.

Washes were carried out in PBS supplemented with 0.2% Tween 20 for cells prepared by the PF/T method.

Flow cytometry analysis.

Samples were analyzed on a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). At least 15,000 cells were gated by light scattering and collected in a list mode manner. Percentages of cells expressing EBV lytic-phase antigens and mean fluorescence intensity were determined on FITC histograms for the cell lines and on dot plots of forward side scatter versus FITC fluorescence for the PBMCs from the patient, using a region defined according to the isotype control analysis. All experiments were run in duplicate in two independent series.

Analysis on PBMCs.

PBMCs from a nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplant recipient with lymphoproliferative disease (17) were obtained from blood samples collected into an EDTA tube by density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Hypaque; Eurobio, Les Ullis, France). PBMCs were then prepared by the PF/M method and stained with MAb AZ125 or IgG2 isotype control, as described for EBV cell lines.

In order to demonstrate viral replication, the presence of ZEBRA mRNA was also determined from RNA extracts obtained from the PBMCs by the RNA-PLUS extraction system (Appligene, Illkirch, France). The BZLF1 reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) assay was carried out in a one-tube reaction with the Superscript one-step RT-PCR system (Life Technologies), with amplification performed as previously described (30).

RESULTS

The technical procedures providing optimal utilization of the four anti-EBV MAbs in flow cytometry were first identified in B95-8 cells cultivated without chemical induction and prepared with paraformaldehyde-methanol. These conditions were then applied to the other cell lines. For the four MAbs used as primary antibodies, incubation at 37°C during 45 min appeared to be adequate (data not shown). No difference was observed when an unpurified MAb was compared with the corresponding FITC-labeled MAb: the optimal concentrations for AZ125 and AR5A9 were, respectively, 1 and 0.5 μg for 5 × 105 cells.

In order to obtain maximum levels of expression of both ZEBRA and Rta antigens, two chemical induction protocols were evaluated on the four selected EBV cell lines (Table 1). Namalwa cells, used as a negative control, never expressed any of the antigens tested for, as expected. Very mild induction of ZEBRA and Rta expression was observed in RAJI cells stimulated by TPA alone, but the addition of n-butyrate during chemical induction led to a 10-fold increase in the levels expressed of both antigens. This was observed with each related MAb. In the two other cell lines (B95-8 and P3HR1) expressing basically ZEBRA and Rta antigens, incubation with TPA and n-butyrate induced a three- to fivefold increase of the percentage of cells expressing both antigens and was associated with a higher mean fluorescence intensity, especially with MAb AZ125 and MAb AR5A9.

TABLE 1.

Replication-phase antigen expression evaluated by flow cytometry for four cell lines that were not induced, stimulated with TPA alone, or stimulated with a mixture of TPA and n-butyrate

| Cell linea | Anti-EBV MAbb | Mean percentage ± SD (mean fluorescence intensity) of cells expressing EBV antigenc

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No induction | TPA | TPA + n-butyrate | ||

| B95-8 | AZ125 | 11 ± 1.5 (80) | 13 ± 0.5 (83) | 30 ± 5 (160) |

| AZ130 | 4 ± 2 (19) | 10 ± 1 (21) | 30 ± 5 (51) | |

| AR8C12 | 8 ± 0.9 (38) | 11 ± 2 (44) | 28 ± 3 (32) | |

| AR5A9 | 9.5 ± 1 (45) | 11 ± 1.5 (20) | 27 ± 4 (85) | |

| P3HR1 | AZ125 | 5 ± 0.5 (75) | ND | 39 ± 2 (98) |

| AZ130 | 6 ± 0.1 (25) | ND | 34 ± 3.5 (42) | |

| AR8C12 | 4.5 ± 0.2 (30) | ND | 37 ± 2 (50) | |

| AR5A9 | 5.1 ± 0.3 (35) | ND | 36 ± 5 (83) | |

| RAJI | AZ125 | <0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.3 (45) | 16 ± 6 (90) |

| AZ130 | <0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 (20) | 14 ± 2 (45) | |

| AR8C12 | <0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.3 (28) | 18 ± 3 (48) | |

| AR5A9 | <0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.2 (30) | 17 ± 4 (65) | |

| Namalwa | AZ125 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| AZ130 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | |

| AR8C12 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | |

| AR5A9 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | |

Cells were fixed and permeabilized by the PF/M method.

Used as ascitic fluid diluted at 1/1,000 or 1/2,000.

SD, standard deviation. ND, not determined.

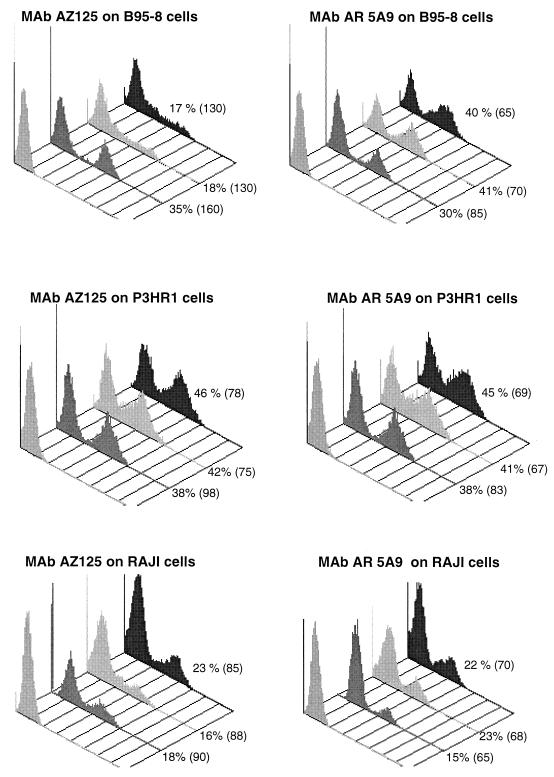

The four protocols for fixation and permeabilization were compared by running them in parallel with the four cell lines cultivated for 3 days in the presence of TPA and n-butyrate (Fig. 1). Levels of antigen expression were assessed with the two MAbs yielding the highest mean fluorescence, AZ125 and AR5A9, with each of the four fixation-permeabilization procedures. Namalwa cells never expressed lytic-phase antigens, whichever protocol was used (data not shown), confirming that no nonspecific labeling occurred with the two selected MAbs.

FIG. 1.

Flow cytometry analysis of ZEBRA (MAb AZ125, 1 μg/assay) and Rta (MAb AR5A9, 0.5 μg/assay) antigen expression on three cell lines stimulated by TPA plus n-butyrate and prepared by three different fixation-permeabilization procedures: (left to right) isotype control, PF/M, Intraprep, and Fix&Perm. Percentages are the portions of cells expressing the related antigen. Mean fluorescence intensity is in parentheses.

Cell preparation with paraformaldehyde and Tween 20 always led to a significant underestimation of both ZEBRA and Rta antigens (data not shown). Percentages of cells expressing ZEBRA or Rta were always below 15% for the three cell lines, and related mean fluorescence intensities were less than 50, leading to a poor discrimination between positive and negative cells.

A comparison of the three other fixation-permeabilization procedures used on the three cell lines expressing EBV antigens is shown in Fig. 1. After induction with TPA and n-butyrate, the expression of lytic-phase antigens by B95-8 and P3HR1 cells reached the same level, which was twice that obtained by the RAJI line. It is interesting that, when each procedure for preparing cells of each cell line is considered alone, levels of expression of both ZEBRA and Rta antigens were similar, except for B95-8 cells evaluated with AZ125 on cells prepared with the two commercially available methods. In this cell line, cell preparation with Intraprep or Fix&Perm led to underestimation of ZEBRA expression (17% positive cells; mean fluorescence intensity, 130) in comparison to that obtained with the PF/M method (35% positive cells; mean fluorescence intensity, 160). For the two other cell lines (RAJI and P3HR1), preparation with these two commercially available methods yielded a somewhat higher percentage of cells expressing the two antigens. However, mean fluorescence intensities were still higher when the PF/M method, which allowed better separation between negative and positive cells, was used.

These observations led us to select the PF/M method as the best procedure for preparing cells.

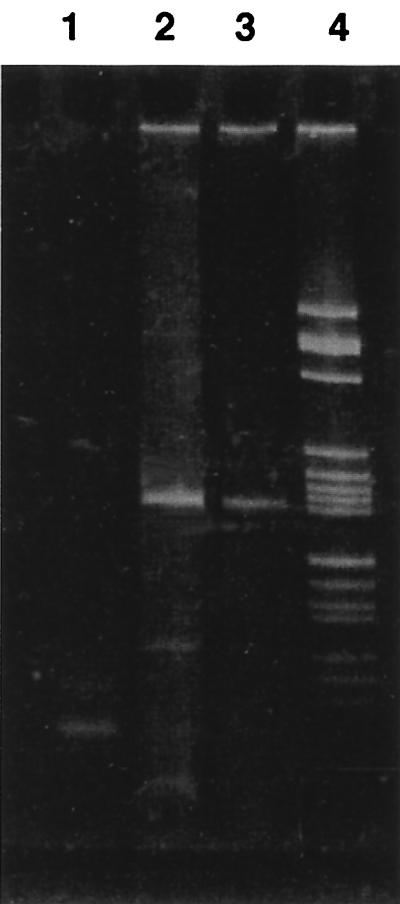

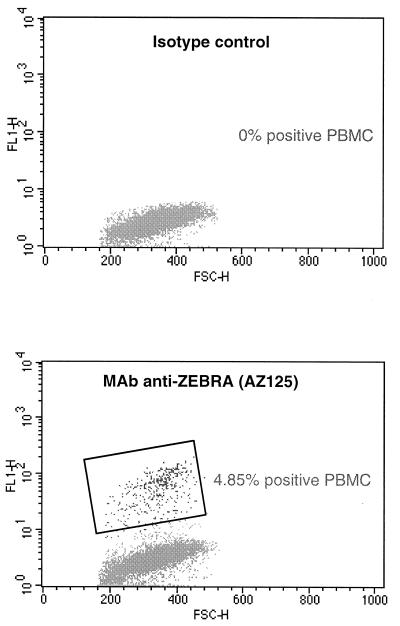

For a preliminary assessment of the feasibility of our technical procedure in the clinical situation, we tested PBMCs from a patient with a major EBV lymphoproliferative disorder for ZEBRA antigens. Occurence of viral replication was assessed by the detection of ZEBRA RNA messenger in PBMCs (Fig. 2). Flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 3) also revealed the presence of ZEBRA antigens in about 5% of this patient's PBMCs.

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR amplification of ZEBRA mRNA (182 bp) in PBMCs obtained from a bone marrow transplant recipient with EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disease (lane 3). Lanes 1 and 2, negative and positive controls, respectively; lane 4, size marker V (Boehringer).

FIG. 3.

Biparametric analysis by forward angle light scatter (FSC-H) versus FITC fluorescence intensity (FL1-H) of MAb AZ125 and related isotype staining on PBMCs from a bone marrow transplant recipient with EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disease. The windows identify EBV-positive PBMCs.

DISCUSSION

EBV has been shown to remain latent in resting B lymphocytes in peripheral blood. This creates a reservoir of virus in contrast to lytic virus replication, which is thought to be restricted to differentiated epithelial cells in vivo. Recent studies using RT-PCR, and immunochemical techniques (20) have demonstrated that B cells in peripheral blood are a major site of virus production during primary infection (for a review, see reference 26). In rare cases, EBV leads to chronic active infection, which is characterized by persistent symptoms and signs of infectious mononucleosis, including persistent B-cell lymphocytosis. In such patients, EBV strains show strongly enhanced activity of the master lytic-phase gene ZEBRA (9). Lytic-cycle replication in reactivated B cells may also be associated with B-cell lymphomas and lymphoproliferative disease (LPD), by shortening tumor latency and increasing the transformation of previously uninfected bystander B cells (23).

We therefore focused our attention on ZEBRA/Rta expression with the versatile FACS methodology. This approach has previously been used in the context of EBV to detect latent or lytic-phase RNA in EBV cell lines by in situ hybridization (4, 12, 27). Some studies have also used flow cytometry to detect EA-D or EA-R, EBV antigens expressed later in the replication cycle (10, 14). One study reported the use of this technology to detect ZEBRA antigens expressed by anti-IgG-stimulated AKATA cells (29). Our aim was to develop and optimize a simple technical procedure for the rapid quantification of immediate-early EBV antigens by flow cytometry.

The first step of our study was to identify which conditions for lytic-phase induction led to the highest levels of antigen expression, which would then allow us to accurately evaluate the optimal conditions for detecting those antigens with flow cytometry. Baseline levels of expression of ZEBRA antigen in the cell lines observed by flow cytometry agreed closely with those obtained with BZ.1 antibody under light microscopy (7). Not surprisingly, stimulation with the TPA plus butyrate combination led to a very significant increase of immediate-early antigens in all three cell lines. In RAJI cells, the procedure caused about 20% of the cells to enter the lytic phase, as previously observed for EA-D (10). We also noted that expression of both Rta and ZEBRA antigens, which are known to be expressed simultaneously (21), reached similar quantitative levels, too.

These findings thus allowed us to evaluate the specificity and reactivity of the four anti-EBV MAbs used in our study. We then decided to retain only two of the four antibodies, AZ125 and AR5A9, which yielded the highest fluorescence intensities and hence allowed better discrimination between nonexpressing and expressing cells.

Selecting and optimizing the techniques used to prepare the cells is a very important step in the adaptation of flow cytometry to herpesvirus antigen detection, since they are located in the nucleus. Four fixation-permeabilization methods were selected and evaluated in parallel. All used paraformaldehyde, which provides good stabilization of permeabilized membranes (preventing the linkage of intracellular proteins with extracellular molecules) and increases the indirect fluorescence of intranuclear antigen (19). For permeabilization, several different reagents were evaluated. Methanol is the most widely used reagent in the study of viral antigens by flow cytometry; it allows such antigens to be conserved over a long period (15) and increases the fluorescence of intracellular antigens (24). The second procedure selected for our study used Tween 20, which provides better preservation both of the staining of surface antigen (important in the selection of B lymphocytes) and of measurements of light scatter (15). Finally, for the two commercially available techniques, Fix&Perm and Intraprep, the exact formulae of the reagents for permeabilization were not disclosed to use by their respective manufacturers, but both contain saponin, whose efficacy in the investigation of nuclear viral antigens has never, to our knowledge, been evaluated.

Of the four procedures we tested, the one using Tween 20 was rapidly eliminated because it led to a substantial underestimation of antigen expression levels in all three cell lines. This was probably due to the fact that Tween 20 produces too gentle a permeabilization of the membrane and thus does not allow the antibody to reach its nuclear target (25). The other three techniques led to broadly similar results. With the two techniques using saponin, Fix&Perm and Intraprep, higher percentages of cells expressing both antigens were obtained than with the PF/M technique on two of the cell lines, P3HR1 and RAJI. This finding shows that saponin produces satisfactory permeabilization of the nuclear membranes. However, fluorescence intensity was lower, which could impair discrimination between positive and negative cells and lead to a less accurate estimation of the percentage of cells expressing antigen. Finally, one of the principal limits of these two techniques from the point of view of routine laboratory use is that testing cannot be delayed. We therefore opted for the PF/M technique, which combines the possibility of storing methanol-treated cells at −70°C for more than a year without detectable loss of their internal antigen content (15) and with a greater fluorescence intensity. This technique is also the one previously chosen for the detection of cytomegalovirus antigen in polymorphonuclear leukocytes by flow cytometry (8).

Preliminary evaluation of our procedure on PBMCs treated by PF/M was successful, in that we were able to demonstrate ZEBRA expression in the whole PBMCs from a patient with a lymphoproliferative disease. However, it should be noted that this was in the very specific context of extensive lymphoproliferation occurring in a patient who had received a nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation (17).

Our study shows that the use of flow cytometry to detect lytic-phase EBV antigens is feasible. Flow cytometry's main advantages are that it allows objective quantification of cells expressing antigens and it detects low levels of antigen expression with a higher sensitivity than immunomicroscopy. We are currently adapting our technique to quantify B cells in the lytic phase in immunodepressed patients, using a double-labeling procedure. This allows B lymphocytes to be first targeted and then evaluated for EBV antigens. Such an approach has been already successfully applied to the direct quantification of cytomegalovirus antigens in polymorphonuclear cells (8).

REFERENCES

- 1.Babcock G J, Decker L L, Freeman R B, Thorley-Lawson D A. Epstein-Barr virus-infected resting memory B cells, not proliferating lymphoblasts, accumulate in the peripheral blood of immunosuppressed patients. J Exp Med. 1999;190:567–576. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.4.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogedain C, Alliger P, Schwarzmann F, Marschall M, Wolf H, Jilg W. Different activation of Epstein-Barr virus immediate-early and early genes in Burkitt lymphoma cells and lymphoblastoid cell lines. J Virol. 1994;68:1200–1203. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.1200-1203.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brousset P, Knecht H, Rubin B, Drouet E, Chittal S, Meggetto F, Al Saati T, Bachmann E, Denoyel G, Sergeant A, Delsol G. Demonstration of Epstein-Barr virus replication in Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin's disease. Blood. 1993;82:872–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crouch J, Leitenberg D, Smith B R, Howe J G. Epstein-Barr virus suspension cell assay using in situ hybridization and flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1997;29:50–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drouet E, Chapuis-Cellier C, Garnier J L, Touraine J L. Early detection of Epstein-Barr virus infection and meaning in transplant patients. In: Touraine J L, et al., editors. Cancer in transplantation. Prevention and treatment. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. pp. 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drouet E, Brousset P, Fares F, Icart J, Verniol C, Meggetto F, Schlaifer D, Desmorat-Coat H, Rigal-Huguet F, Niveleau A, Delsol G. High Epstein-Barr virus serum load and elevated titers of anti-ZEBRA antibodies in patients with EBV-harboring tumor cells of Hodgkin's disease. J Med Virol. 1999;57:383–389. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199904)57:4<383::aid-jmv10>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flamand L, Stefanescu I, Ablashi D V, Menezes J. Activation of the Epstein-Barr virus replicative cycle by human herpesvirus 6. J Virol. 1993;67:6768–6777. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6768-6777.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imbert-Marcille B-M, Robillard N, Poirier A-S, Coste-Burel M, Cantarovich D, Milpied N, Billaudel S. Development of a method for direct quantification of cytomegalovirus antigenemia by flow cytometry. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2665–2669. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2665-2669.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jager M, Prang N, Mitterer M, Larcher C, Huemer H P, Reischl U, Wolf H, Schwarzmann F. Pathogenesis of chronic Epstein-Barr virus infection: détection of virus strain with high rate of lytic replication. Br J Haematol. 1996;95:626–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenson H B, Grant G M, Ench Y, Heard P, Thomas C A, Hilsenbeck S G, Moyer M P. Immunofluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry characterization of chemical induction of latent Epstein-Barr virus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:91–97. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.1.91-97.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joab I, Nicolas J C, Schwaab G, De The G, Clausse G, Perricaudet M, Zeng Y. Detection of anti-Epstein-Barr virus transactivation (ZEBRA) antibodies in sera from patients with nasopharyngal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1991;48:647–649. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910480503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Just T, Burgwald H, Kjaervig Broe M. Flow cytometry detection of EBV (EBERs mRNA) using peptide nucleic acid probe. J Virol Methods. 1998;73:163–174. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz B Z, Raab-Traub N, Miller G. Latent and replicating forms of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in lymphomas and lymphoproliferative disease. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:589–598. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lidin B, Gartland L, Marshall G, Sanchez V, Lamon E W. Detection of two early gene products of Epstein-Barr virus by fluorescence flow cytometry. Viral Immunol. 1993;6:97–107. doi: 10.1089/vim.1993.6.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mc Sharry J. Uses of flow cytometry in virology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:576–604. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.4.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller G. The switch between latency and replication of Epstein-Barr virus. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:833–844. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milpied N, Coste-Burel M, Accard F, Moreau A, Moreau P, Garand R, Harousseau J-L. Epstein-Barr virus associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disease after non myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:629–630. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyashita E M, Yang B, Lam K M, Crawford D H, Thorley-Lawson D A. A novel form of Epstein-Barr virus latency in normal B cells in vivo. Cell. 1995;80:595–601. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollice A, McCoy J, Shackney S, Smith C, Agarwal J, Burholt D, Janocko L, Hornicek F, Singh S, Hartsock R. Sequential paraformaldehyde and methanol fixation for simultaneous flow cytometric analysis of DNA, cell surface proteins, and intracellular proteins. Cytometry. 1992;13:432–444. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990130414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prang N S, Hornef M W, Jager M, Wagner H J, Wolf H, Schwarzmann F M. Lytic replication of Epstein-Barr virus in the peripheral blood: analysis of viral gene expression in B lymphocytes during infectious mononucleosis and in normal carrier state. Blood. 1997;89:1665–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ragoczy T, Heston L, Miller G. The Epstein-Barr virus Rta protein activates lytic cycle genes and can disrupt latency in B lymphocytes. J Virol. 1998;72:7978–7984. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7978-7984.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rickinson A B, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2397–2446. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rochford R, Mosier D E. Differential Epstein-Barr virus gene expression in B-cell subsets recovered from lymphomas in SCID mice after transplantation of human peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Virol. 1995;69:150–155. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.150-155.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schimenti K, Jaccobberger J. Fixation of mammalian cells for flow cytometric evaluation of DNA content and nuclear immunofluorescence. Cytometry. 1992;13:48–59. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990130109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmid I, Uittenbogaart H, Giorgi J. A gentle fixation and permeabilization method for combined cell surface and intracellular staining with improved precision in DNA quantification. Cytometry. 1991;12:279–285. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990120312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwarzmann F, Jager M, Hornef M, Prang N, Wolf H. Epstein-Barr viral gene expression in B-lymphocytes. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;30:123–129. doi: 10.3109/10428199809050935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stowe R P, Cubbage M L, Sams C F, Pierson D L, Barrett A D T. Detection and quantification of Epstein-Barr virus EBER1 in EBV-infected cells by fluorescent in situ hybridization and flow cytometry. J Virol Methods. 1998;75:83–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Straus S E, Cohen J I, Tosato G, Meier J. Epstein-Barr virus infections: biology, pathogenesis, and management. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:45–58. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-1-199301010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takase K, Kelleher C A, Terada N, Jones J F, Lucas J J, Gelfand E W. Dissociation of EBV genome replication and host cell proliferation in anti-IgG-stimulated Akata cells. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;81:168–174. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tierney R J, Steven N, Young L S, Rickinson A B. Epstein-Barr virus latency in blood mononuclear cells: analysis of viral gene transcription during primary infection and in the carrier state. J Virol. 1994;68:7374–7385. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7374-7385.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]