INTRODUCTION

Although sex and ethnoracial diversity in the health profession is associated with improved healthcare access and quality, physician diversity has remained stagnant compared to the diverse US population. While Black males account for 6.4% of the population, they make up less than 3.0% of all physicians.1 Although the number of female and ethnoracial underrepresented students enrolled in medical schools has increased since the implementation of the Liaison Committee on Medical Education diversity standards,2 their retention remains unknown. To fill this knowledge gap, we examined the retention of medical students across intersectional sex and ethnoracial identity using a national cohort of medical students. Understanding the retention of diverse students from matriculation to medical school graduation is essential to promote healthcare workforce diversity.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of US MD matriculants to all US allopathic medical schools in academic years 2014–2015 and 2015–2016 using individual-level de-identified data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Student Records System. Students’ sex, ethnoracial identity, parental education, and age at matriculation were self-reported. Ethnoracial identity included White, Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN), Hawaiian Native/Pacific Islander (HNPI) alone, multiracial and Unknown/Other. In intersection analysis of sex-ethnoracial groups, AIAN, HNPI, Unknown/Other, and multiracial students were grouped into one Unknown/Other category due to small sample size. Students’ most recent first-attempt Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) was also obtained from the AAMC. Students were categorized as first-generation college graduates if neither parent held a four-year college degree. We obtained attrition status (withdrawal or dismissal for any reason) in September 2020, providing a 5-year follow-up for all students. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine odds of attrition, adjusting for MCAT quartiles calculated from the study cohort,, parental education background, and age at matriculation, which have been shown to influence students’ academic outcomes.3 Our analyses were conducted according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines. This study was deemed exempt by the Yale Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Among 37,003 MD matriculants, 35,216 (95.2%) graduated, 1,069 (2.9%) left medical school, and 718 (1.9%) were still enrolled in medical school and had not yet graduated. After excluding these 718 students and 4 students with unknown sex, and 622 students with MCAT scores not reported on the AMCAS application, our study cohort included 36,281 students.

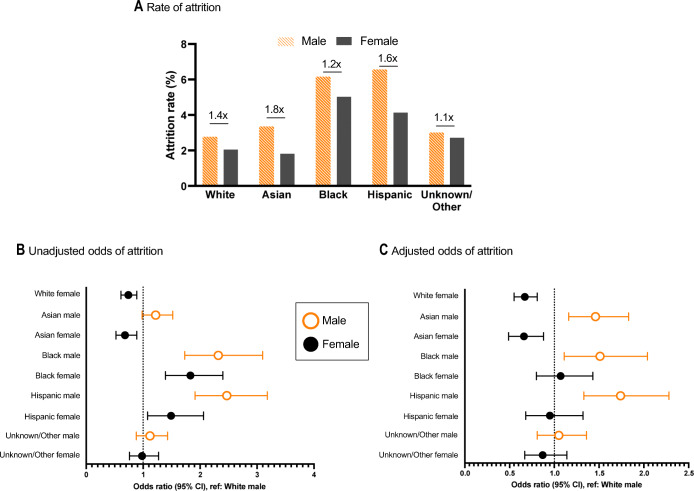

Compared to students who graduated, a lower proportion of students who left medical school identified as female (40.5% vs. 48.0, p < 0.001), White (45.1% vs. 54.1%, p < 0.001), non-first-generation college graduate (82.8% vs. 74.6%, p < 0.001), matriculated at age less than 23 years old (31.3% vs. 37.0%, p < 0.001), and had MCAT scores in the top quartile (17.2% vs. 29.4%, p < 0.001, Table 1). Across all ethnoracial groups, attrition rate was greatest for male students (Fig. 1a), with the greatest sex difference between Asian male and female students (3.2% vs. 1.8%, p < 0.001). In unadjusted models, compared to White male students, Black and Hispanic female and male students were more likely to attrit (Fig. 1b), while White and Asian female students were less likely to attrit.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medical School MD Matriculants

| Attrition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No | Yes | p-value | |

| N = 35,679 | N = 34,635 | N = 1,044 | ||

| Sex | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 18,686 (52.4%) | 18,062 (52.1%) | 624 (59.8%) | |

| Female | 16,993 (47.6%) | 16,573 (47.9%) | 420 (40.2%) | |

| Ethnoracial identity | < 0.001 | |||

| White | 19,226 (53.9%) | 18,754 (54.1%) | 472 (45.2%) | |

| Asian | 6,540 (18.3%) | 6,370 (18.4%) | 170 (16.3%) | |

| Black | 2,236 (6.3%) | 2,113 (6.1%) | 123 (11.8%) | |

| Hispanic | 2,264 (6.3%) | 2,141 (6.2%) | 123 (11.8%) | |

| Unknown/Other | 5,413 (15.2%) | 5,257 (15.2%) | 156 (14.9%) | |

| Sex-ethnoracial identity | < 0.001 | |||

| White male | 10,509 (29.5%) | 10,216 (29.5%) | 293 (28.1%) | |

| Asian male | 3,287 (9.2%) | 3,176 (9.2%) | 111 (10.6%) | |

| Black male | 922 (2.6%) | 865 (2.5%) | 57 (5.5%) | |

| Hispanic male | 1,201 (3.4%) | 1,122 (3.2%) | 79 (7.6%) | |

| Unknown/Other male | 2,767 (7.8%) | 2,683 (7.7%) | 84 (8.0%) | |

| White female | 8,717 (24.4%) | 8,538 (24.7%) | 179 (17.1%) | |

| Asian female | 3,253 (9.1%) | 3,194 (9.2%) | 59 (5.7%) | |

| Black female | 1,314 (3.7%) | 1,248 (3.6%) | 66 (6.3%) | |

| Hispanic female | 1,063 (3.0%) | 1,019 (2.9%) | 44 (4.2%) | |

| Unknown/Other female | 2,646 (7.4%) | 2,574 (7.4%) | 72 (6.9%) | |

| First-generation college graduate | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 29,454 (82.6%) | 28,671 (82.8%) | 783 (75.0%) | |

| Yes | 5,361 (15.0%) | 5,148 (14.9%) | 213 (20.4%) | |

| Missing | 864 (2.4%) | 816 (2.4%) | 48 (4.6%) | |

| Age at matriculation | < 0.001 | |||

| Less than 23 years old | 13,032 (36.5%) | 12,715 (36.7%) | 317 (30.4%) | |

| Greater or equal to 23 years old | 22,647 (63.5%) | 21,920 (63.3%) | 727 (69.6%) | |

| MCAT quartiles | < 0.001 | |||

| 1st (lowest) | 7,937 (22.2%) | 7,498 (21.6%) | 439 (42.0%) | |

| 2nd | 110,503 (29.4%) | 10,211 (29.5%) | 292 (28.0%) | |

| 3rd | 7,314 (20.5%) | 7,160 (20.7%) | 154 (14.8%) | |

| 4th (highest) | 9,925 (27.8%) | 9,766 (28.2%) | 159 (15.2%) | |

Figure 1.

Medical school attrition by sex and ethnoracial identity. (A) Attrition rate for male (orange) and female (gray) students by race/ethnicity for matriculants to medical school between 2014–2015 and 2015–2016, and ratios of male to female attrition rates. (B) Unadjusted odds of attrition with 95% confidence interval. (C) Adjusted odds of attrition with 95% confidence interval, adjusted for students’ first-attempt MCAT scores, age at matriculation, and first-generation college graduate status.

In our fully adjusted model, compared to White male students, Asian male (aOR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.16–1.83), Black male (aOR: 1.50, 95% CI: 1.11–2.03), and Hispanic male (aOR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.33–2.27) students were more likely to leave medical school. No difference was found for Black and Hispanic female students (Fig. 1c), while White female (aOR: 0.67, 95% CI: 0.55–0.81) and Asian female (aOR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.49–0.88) students were less likely than their White male peers to leave medical school.

Discussion

We observed significant inequities in attrition from medical school across sex and ethnoracial identities. Specifically, Asian, Black, and Hispanic male students were at least 40% more likely than their White male peers to leave medical school.

Men of color face multiple added challenges during medical school, including racism, discrimination, and mistreatment.4 Persistent negative portrayals and lower expectations for men of color lead to internalization of stereotypes and biases, as well as racial fatigue, which could negatively affect education outcomes.5 Furthermore, although role models and mentors are critical for career development, the disparate underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic men in academic medicine creates a mentorship deficit.6

Because students leave medical school for many reasons, both academic and non-academic, future studies must explore reasons for attrition for Asian, Black, and Hispanic men. Our study is limited in that we do not know attrition rates after year 5 of medical school. Furthermore, disaggregation of ethnoracial groups, specifically for Asian and AIAN male and female students, is critical to understand and promote equitable retention strategies for underrepresented students. Addressing inequities in medical student attrition promises to benefit not only students but their medical schools, the US healthcare system, and patients.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Association of American Medical Colleges. Altering the Course: Black Males in Medicine. Washington, DC 2015.

- 2.Boatright DH, Samuels EA, Cramer L, et al. Association Between the Liaison Committee on Medical Education’s Diversity Standards and Changes in Percentage of Medical Student Sex, Race, and Ethnicity. JAMA. 2018;320(21):2267–2269. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen M, Song SH, Ferritto A, Ata A, Mason HRC. Demographic Factors and Academic Outcomes Associated With Taking a Leave of Absence From Medical School. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(1):e2033570–e2033570. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson N, Lett E, Asabor EN, et al. The Association of Microaggressions with Depressive Symptoms and Institutional Satisfaction Among a National Cohort of Medical Students. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;37(2):298–307. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06786-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nunez-Smith M, Curry LA, Bigby J, Berg D, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH. Impact of race on the professional lives of physicians of African descent. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(1):45–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-1-200701020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine . An American Crisis: The Growing Absence of Black Men in Medicine and Science: Proceedings of a Joint Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]