Abstract

Background

Black patients in the USA are disproportionately affected by chronic pain, yet there are few interventions that address these disparities.

Objective

To determine whether a walking-focused, proactive coaching intervention aimed at addressing contributors to racial disparities in pain would improve chronic pain outcomes among Black patients compared to usual care.

Design

Randomized controlled trial with masked outcome assessment (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01983228).

Participants

Three hundred eighty Black patients at the Atlanta VA Health Care System with moderate to severe chronic back, hip, or knee pain.

Intervention

Six telephone coaching sessions over 8–14 weeks, proactively delivered, using action planning and motivational interviewing to increase walking, or usual care.

Main Measures

Primary outcome was a 30% improvement in pain-related physical functioning (Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire [RMDQ]) over 6 months among Black patients, using intention-to-treat. Secondary outcomes were improvements in pain intensity and interference, depression, anxiety, global impression of change in pain, and average daily steps.

Key Results

The intervention did not produce statistically significant effects on the primary outcome (at 6 months, 32.4% of intervention participants had 30% improvement on the RMDQ vs. 24.7% of patients in usual care; aOR=1.61, 95% CI, 0.94 to 2.77), nor on other secondary outcomes assessed at 6 months, with the exception that intervention participants reported more favorable changes in pain relative to usual care (mean difference=−0.54, 95% CI, −0.85 to −0.23). Intervention participants also experienced a significant reduction in pain intensity and pain interference over 3 months (mean difference=−0.55, 95% CI, −0.88 to −0.22).

Conclusions

A novel intervention to improve chronic pain among Black patients did not produce statistically significant improvements on the primary outcome relative to usual care. More intensive efforts are likely required among this population, many of whom were economically disadvantaged and had mental health comorbidities and physical limitations.

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01983228

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-07376-2.

KEY WORDS: chronic pain, walking, African Americans, vulnerable populations

BACKGROUND

Chronic pain is a prevalent, debilitating, and costly national problem.1 Despite its prevalence and burgeoning costs, conventional biomedical strategies have proved inadequate, and, in the case of opioid-centric treatment, have led to a precipitous increase in deaths, as well as significant increases in opioid abuse and addiction.2 Hence, there is a pressing need for new nonpharmacological pain treatment approaches, informed by a biopsychosocial framework.

Decades of research show that Black patients in the USA are disproportionately affected by chronic pain compared to non-Hispanic Whites, experiencing more severe and debilitating pain.1,3–6 Contributors to these disparities are multi-level and linked to systemic racism.5,7,8 Blacks are more likely to have unmet medical needs due to myriad factors, including lack of insurance and underinsurance7 and experiences of racism within and outside the healthcare system that are associated with avoiding and delaying care.9 Blacks are more likely to have their pain undertreated, discounted, and underestimated,5,7 due in part to provider stereotypes and biases.5,10 Furthermore, Blacks experience poorer quality communication with their providers, which can adversely affect the quality of pain treatment.5 Blacks are also more likely to hold beliefs and engage in coping strategies that contribute to poor pain outcomes (e.g., pain catastrophizing, pain-related fear of movement, lower self-efficacy in coping with pain).11–14 In addition, Blacks experience an array of system-level contributors to pain ranging from racial discrimination, associated with greater pain and factors that exacerbate pain such as poorer mental and physical health8,15,16 and lower levels of physical activity,17,18 and environmental barriers to exercise19 associated with racial segregation.20

The primary aim of this randomized controlled trial was to test whether a walking-focused, proactive coaching intervention (ACTION) based on a biopsychosocial framework, aimed at addressing contributors to racial disparities in pain, would lead to greater improvement in chronic pain outcomes among Black patients, relative to usual care. ACTION uses proactive outreach, a systems-level model of patient engagement that systematically identifies and reaches out to patients to connect them with treatment. Proactive outreach has been used to address utilization barriers experienced by minority and low-income groups, in providing treatment for smoking,21,22 and substance dependence.23 ACTION uses action planning and motivational interviewing (MI) to promote walking, which numerous studies have shown to be an effective nonpharmacologic treatment for chronic pain.24,25 Action planning—making a specific plan that specifies where and how the behavior will be performed—is especially well-suited for enabling individuals to overcome environmental and psychological barriers.26 Motivational interviewing—a patient-centered approach for facilitating behavior change—can foster high-quality communication and empower participants to overcome barriers to exercise.27Meta-analyses have shown action planning26 and motivational interviewing27 to be effective behavioral change strategies, including for promoting physical activity.28,29 The intervention was further tailored through feedback obtained from focus groups of Black VA patients with chronic pain.30 Table 1 depicts how intervention components were designed to address contributors to racial disparities in pain.

Table 1.

Key Intervention Components to Address Racial Disparities in Pain

| Intervention component | How component addresses contributors to racial disparities in pain |

|---|---|

| Proactive outreach |

- Addresses unmet medical needs related to experiences of discrimination within and outside the healthcare system - Addresses provider-, healthcare-, and larger system-level barriers to pain treatment, including non-pharmacological approaches - Tailored recruitment materials developed with input from Black VA patients with chronic pain address barriers to pain care (e.g., barriers related to trust in VA; barriers related to utilizing non-pharmacological treatment options for chronic pain such as access and knowledge) |

| Telephone delivery |

- Addresses healthcare barriers related to access (e.g., transportation, time to travel to VA, physical barriers) - Addresses healthcare barriers related to healthcare discrimination/trust in VA, because care was delivered outside the VA facility |

| Supportive, culturally competent coaches trained in motivational interviewing |

- Addresses provider barriers related to trust and patient-provider communication - Continual training to help coaches understand experiences of Black VA patients with chronic pain (e.g., environmental barriers to walking) |

| Action planning |

- Addresses psychological and environmental barriers, as action planning increases the likelihood that individuals will perform intended behaviors and overcome barriers - Participants coached in “coping planning” (i.e., making plans that addresses barriers to walking) and “facilitative planning,” (i.e., creating plans to make walking easier) |

| Motivational interviewing and psychoeducation | Addresses psychological barriers (self-efficacy, pain-related fear avoidance, catastrophizing) |

As part of our secondary aims, we explored the effectiveness of this intervention among non-Black Veterans, since we expected that they might experience some of the same contributors to pain that affect Black Veterans. For example, chronic pain patients experience frustration with their treatment of pain and report feeling stigmatized by their providers.31 Veterans are also considered to be a vulnerable group that is at greater risk for pain and poor pain treatment.31 In this paper, we present the results of the primary aims, which include only Black participants. Results involving the full sample are presented in the Appendix. A full description of the study aims and further details about the intervention and methods can be found in our study protocol publication.30

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

The ACTION study was approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board (CIRB) prior to data collection. This was a two-group randomized clinical trial conducted among patients from the Atlanta VA Health Care System (AVAHCS), chosen because it had a large percentage of Black patients (43%). The sampling frame was a random sample of patients from the AVAHCS stratified by race (Black and non-Black), who had at least 1 hip, back, or knee diagnosis code in the electronic health record (EHR) in the past year and a second hip, back, or knee diagnosis code within 18 months of the first one (an approach used to establish reliability of the diagnosis and presence of chronic, as opposed to acute, pain).32 We did not force balance between Black and non-Black participants.

Potentially eligible patients identified from the EHR were recruited using proactive outreach. Patients were mailed a letter and brochure that were developed with input from Black patients with chronic pain. This was followed by telephone screening to ascertain that patients met the following criteria: (1) a pain duration of ≥6 months; (2) moderate-severe pain intensity and interference with function, defined as a score of ≥ 5 on the PEG (Pain intensity, Enjoyment of life, General activity),33,34 a 3-item assessment tool for pain; (3) self-reported ability to walk at least 1 block; and (4) ability to communicate effectively by telephone. Patients who met any of the following exclusion criteria were ineligible: (1) moderately severe cognitive impairment defined as > 2 errors on a brief cognitive screener (the 6-item Callahan screener that identifies cognitive impairment for potential research subjects);35(2) anticipated back, knee, hip, or other major surgery within the next 12 months; (3) unavailable to participate in a 6-month study; and (4) active psychotic symptoms, suicidality, severe depression, and/or active manic episode or poorly controlled bipolar disorder, as determined by chart review.

Participants received an information sheet that was reviewed over the phone by a research assistant and gave oral consent to participate. Consented participants were mailed a pedometer and a baseline survey to complete and return, after which they were randomized to usual care (UC) or the intervention (1:1) and notified by mail.

To ensure treatment was equally balanced on race, randomization was stratified on participant self-identified Black or non-Black status and balance in assignment over time was achieved using permuted block randomization with block sizes of 4, 6, or 8. Allocation concealment methods were designed to maximize internal validity, within the constraints of the study design.36,37 The randomization list was concealed from the research team, and follow-up outcome assessments were conducted mostly by mailed surveys but secondarily by telephone by unblinded research staff trained in unbiased surveying methods who were not involved in the delivery of the intervention.

Procedures

Usual care

UC participants received a brochure, “Chronic Pain, Walking & You,” with advice and information about the benefits of walking and a pedometer, which they were instructed to use and record their steps with, the week before the baseline and follow-up surveys.

Intervention

Intervention participants received a pedometer and tailored materials (a letter and brochure) describing the program and the benefits of walking and physical activity to help manage pain. Materials were developed with iterative feedback from 4 focus groups conducted with Black patients with chronic pain at the AVAHCS. The manualized, ACTION intervention consisted of 6, individual 30- to 60-min telephone coaching sessions over an 8–14-week period, delivered by counselors trained in MI. Participants were coached to create and write action plans for their proposed walking activity, during the week(s) between coaching sessions, using templates contained in their workbooks. Counselors were also trained to help participants develop specific types of action plans to overcome barriers, strengthen helpful factors, and involve friends and family members. Pedometers were used as a tool to promote walking through feedback, goal setting, and monitoring.38 Details of the coaching sessions are presented in the Appendix (Table 4) and described in the associated publication.30

Description of Measures and Data Collection Procedures

Data collection was conducted by mail at baseline, and a combination of mail and telephone at 3 and 6 months post-randomization. We used modified Dillman mail survey procedures, which have been previously described.30 Participants received $20 for each survey they completed.

Outcomes

Pain outcomes were based on four outcome domains recommended by the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT)39 guidelines: pain-related physical functioning, emotional functioning, pain intensity, and participant ratings of overall improvement. Outcomes were assessed at the 3- and 6-month follow-up surveys. The primary outcome was a 30% improvement in physical functioning at 6 months relative to baseline, assessed by the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ),40 which is the accepted threshold for clinically significant improvement in clinical trials.40 Pain intensity and interference was assessed by the 0–10 numerical rating scale from the 3-item PEG.33,34 Emotional functioning was assessed by the Personal Health Questionnaire Depression scale (PHQ-8),41 without the suicidality item (8 items), and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7)42 scale. Participant ratings of change in their overall level of pain was assessed by the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) scale, a single-item, 7-point scale, which asked participants to describe their level of pain now compared to their pain 3 months ago (anchored by 1 (much better) and 7 (much worse)).43

Walking was measured by the number of average daily steps, using pedometer readings recorded in walking logs, based on seven consecutive days of data. Participants were instructed (via a mailed postcard and reminder phone calls) to wear the pedometer and to record readings on logs over 7 days at the baseline assessment and the 3- and 6-month follow-up time points, which they reported on surveys.

Statistical Analysis

We restricted our analyses to the sample of Black participants. Analyses were based on the intention-to-treat method for all randomized participants.

After assessing data for normality and evidence of balance of baseline factors across intervention groups using Pearson’s χ2 -tests and two-sample t tests, models adjusted for imbalanced variables (use of an opioid medication for pain and the use of a walking aid) were used to estimate the main effects of the intervention on primary and secondary outcomes. Multiple logistic regression was used to model the effect of treatment arm on the dichotomous primary outcome (30% reduction in RMDQ relative to baseline) at 3 and 6 months.

Generalized linear mixed models modeled the effect of the intervention on the continuous secondary outcomes of (1) RMD score, (2) PGIC score, (3) PEG score, (4) PHQ-8 score, (5) GAD score, and (6) step count at 3 and 6 months. These models incorporated a random intercept and specified an unstructured covariance structure to account for within-subject co-variability over time and utilized restricted maximum likelihood. Models also included baseline values of the outcome measure to adjust for baseline differences between the groups. To explore whether intervention effects differed at 3 and 6 months, analyses also assessed for intervention × time point interactions. These analyses assessed the overall time-averaged intervention effect, as well as simple effects at 3 and 6 months.

To address the potential for bias due to nonignorable missingness at the primary endpoint, we conducted a selection model analysis using methods proposed by Ibrahim and Lipsitz.44 This analysis jointly modeled how the value of the dichotomous outcome (30% reduction in RMDQ vs no reduction) was related to the available predictors (i.e., baseline covariates for all enrolled participants) and whether survey non-response was related to the value of the outcome and the available predictors. An expectation–maximization algorithm was then run to calculate participant weights, which were applied to logistic regressions which modeled the main effect of the intervention on the primary outcome.

Role of the Funding Source

The study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service. The funding source had no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

RESULTS

Study Participants

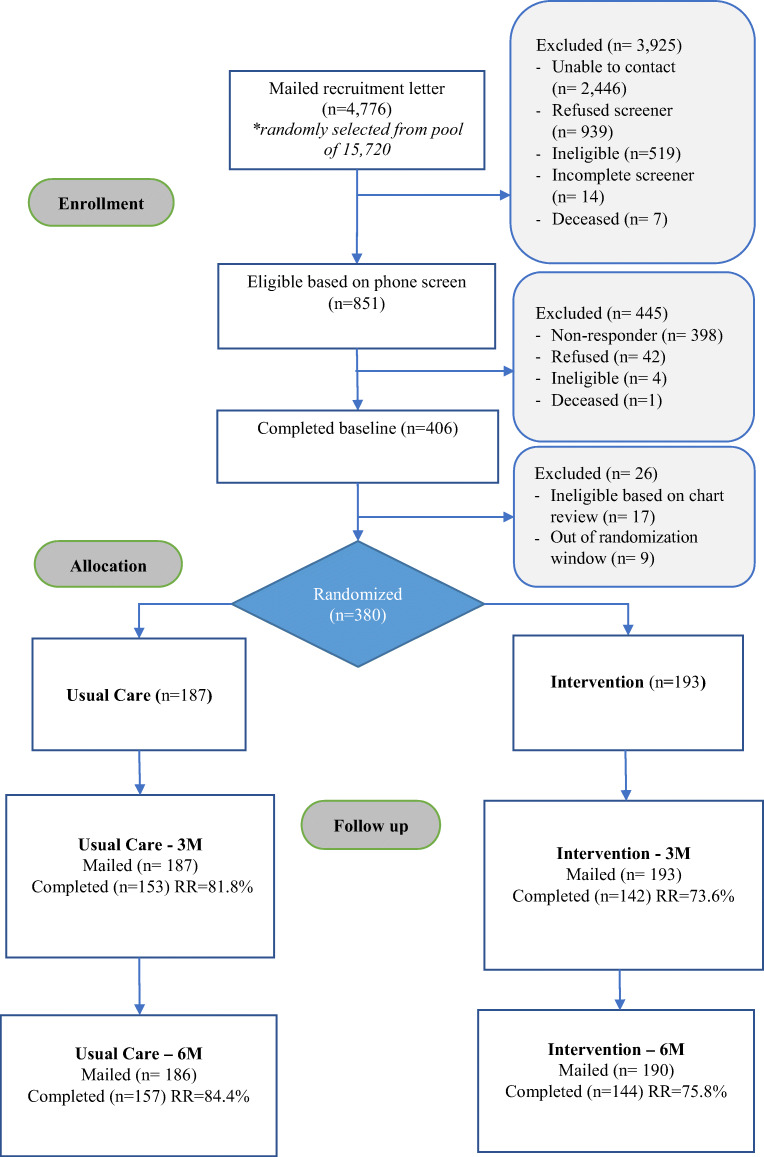

Study participants were recruited from July 2016 to March 2019. Figure 1 delineates participant enrollment and follow-up among Black participants in the ACTION trial (see Appendix for enrollment and follow-up among the full sample). Of the 4,776 Black patients mailed a recruitment packet, 3,925 did not meet the initial eligibility criteria for the following reasons: we were unable to contact them (n=2,446), they refused the phone screen (n=939), or they were ineligible based on their screener responses (n=519). Of the 851participants who were sent a baseline survey, 406 participants returned a completed baseline survey (45.6%). Of these, 17 were ineligible based on EHR review, 9 were out of the randomization window, and 380 were randomized to the intervention (n=193) or to UC (n=187). The 3-month survey response rate was 77.6% (73.6% intervention vs 81.8% UC) and the 6-month survey response rate was 79.2% (75.8% intervention vs 84.4% UC).

Figure 1.

Flow of Black participants through the study.

The sample of Black participants was 72% male with a mean age of 58 (SD, 11) years. Thirty-nine percent were unemployed or unable to work, 27% were retired, and 28% were employed. Sixty percent had a yearly income < $40,000 and only 9% had an income greater than $80,000. Ninety-two percent were treated for pain in the past year, 59% used a walking aid, and 34% reported taking opioids for pain. Fifty-eight percent had PHQ-8 scores > 10 and 43% had GAD-7 scores > 10, indicating moderate depression and moderate anxiety, respectively.42,45Fifty-four percent had at least one mental illness diagnosis in the EHR, the most prevalent of which was a depressive disorder (37%).

The UC (n=187) and intervention (n=193) groups were compared across the demographic, health-related, and pain-related variables presented in Table 2. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the ACTION intervention and UC arms (Table 2), with the exception of walking aids and opioid use.

Table 2.

Baseline Demographic, Health, and Pain-Related Characteristics of Black Participants

| Characteristic | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 193) |

Usual care (n = 187) |

Total (n = 380) |

|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 59 (11) | 58 (10) | 58 (11) |

| Gender, N(%), male | 144 (75) | 130 (70) | 274 (72) |

| Live alone, N(%) | 51 (27) | 50 (27) | 101 (27) |

| Employment status, N(%) | |||

| Employed | 49 (26) | 52 (29) | 102 (28) |

| Unemployed/unable to work | 68 (36) | 77 (42) | 145 (39) |

| Retired | 59 (31) | 41 (23) | 100 (27) |

| Other | 12 (6) | 11 (6) | 23 (6) |

| Yearly income, N(%) | |||

| Less than $40K | 110 (62) | 100 (59) | 210 (60) |

| $40, 001 to $60K | 33 (19) | 34 (20) | 67 (19) |

| $60, 001 to $80K | 23 (13) | 17 (10) | 40 (11) |

| More than $80K | 12 (7) | 19 (11) | 31 (9) |

| Health- and pain-related | |||

| Use walking aids, N(%) | 121 (64) | 96 (53) | 217 (59) |

| BMI, Mean (SD) | 31 (7) | 30 (5) | 31 (6) |

| RMDQ: pain-related physical function (range, 0–11; higher score = worse) | 8 (3) | 7 (3) | 8 (3) |

| PEG: Pain intensity and interference (range, 0–10: higher score = worse), mean (SD) | 7 (1) | 7 (2) | 7 (1) |

| PHQ-8 depression symptoms (range, 0–24: higher score = worse), mean (SD) | 11 (6) | 11 (6) | 11 (6) |

| GAD-7 anxiety symptoms (range, 0–21: higher score = worse), mean (SD) | 9 (6) | 9 (6) | 9 (6) |

| Steps per day, mean (SD) | 3258 (2616) | 3154 (2566) | 3206 (2588) |

| Mental health diagnoses from EHR | |||

| Depressive disorders*, N(%) | 74 (38) | 67 (36) | 141 (37) |

| Anxiety disorders*, N(%) | 19 (10) | 19 (10) | 38 (10) |

| Drug-use disorders*, N(%) | 48 (25) | 36 (19) | 84 (22) |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder*, N(%) | 54 (28) | 45 (24) | 99 (26) |

| Serious Mental Illness*, N(%) | 17 (9) | 11 (6) | 28 (7) |

| Any Mental Health Diagnosis*, N(%) | 105 (54) | 100 (53) | 205 (54) |

| Medication use | |||

| Take opioid for pain, N(%) | 74 (39) | 53 (29) | 127 (34) |

| Frequency of pain medication, N(%) | |||

| Every day | 82 (43) | 76 (42) | 158 (42) |

| Most days | 57 (30) | 41 (22) | 98 (26) |

| At least 1 × week | 24 (13) | 31 (17) | 55 (15) |

| Less than weekly | 27 (14) | 35 (19) | 62 (17) |

| Use of non-pharmacological treatment for pain in past year | |||

| Number of treatments used, mean (SD) | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 4 (3) |

| Treated for pain in VA, past 12 months, N(%) | 160 (86) | 162 (88) | 322 (87) |

| Treated for pain outside VA, past 12 months, N(%) | 73 (39) | 73 (40) | 146 (40) |

| Treated for pain anywhere, past 12 months, N(%) | 169 (92) | 169 (91) | 338 (92) |

*Unless specified, all variables were obtained by self-report

Abbreviations: RMDQ Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire, PEG Pain intensity, Enjoyment of life, General activity; PHQ-8, 8-Item Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7, 7-Item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire

Intervention Engagement

Among the 193 Black participants in the intervention group, 92 (48%) completed all 6 sessions, 22 (11%) completed 3–5 sessions, 30 (15%) completed 1–2 sessions, and 50 (26%) failed to complete any sessions. Among those that completed at least 1 session (n=143), 48 were mailed their 3-month follow-up survey before their final session was recorded.

Primary Outcome

At 6 months, the primary study endpoint, 32.4% (46/142) of Black patients in the intervention had a 30% or more reduction on the RMDQ from baseline compared to 24.7% (38/154) in UC (aOR=1.61, 95% CI, 0.94 to 2.77, p=.09). Sensitivity analyses conducted to address missing data resulted in a slightly attenuated intervention effect estimate at 6 months (aOR=1.54, 95% CI, 0.96 to 2.47, p=.08) compared to complete case analyses.

Secondary Outcomes

At 3 months, 28.8% (40/139) of Black patients in the intervention had a 30% or more reduction on the RMDQ from baseline compared to 22.8% (34/149) in UC (aOR=1.49, 95% CI, 0.85 to 2.62, p=0.16). As can be seen in Table 3, Black intervention participants reported more favorable changes in their levels of overall pain at 6 months relative to those in UC (mean difference=−0.54, 95% CI, −0.85 to −0.23). Analyses of the PEG (pain intensity and interference) scale indicated a significant time × intervention interaction (p=0.025), such that the intervention was associated with significantly lower scores than UC at the 3-month assessment (mean difference=−0.55, 95% CI, −0.88 to −0.22) but not the 6-month assessment. Intervention participants did not show significantly greater improvement in emotional functioning, as assessed by the PHQ-8 and the GAD, or average daily step count, although these estimates were in a direction that favored the intervention.

Table 3.

Secondary Outcomes Among Black Participants Randomized to ACTION Program vs. Usual Care

| Outcomes | Intervention | Usual care | Between-group difference1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean diff (95% CI) | |

| RMDQ | – | ||

| Time × intervention (p-value) | – | – | 0.203 |

| Overall | 7.09 (0.12) | 7.40 (0.12) | −0.32 (−0.65, 0.02) |

| 3 months | 6.71 (0.20) | 7.32 (0.19) | −0.61 (−1.16, −0.06) |

| 6 months | 6.86 (0.20) | 7.30 (0.19) | −0.44 (−0.98, 0.11) |

| Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) scale (range, 1–7: higher score = worse) | |||

| Time × intervention (p-value) | – | – | 0.100 |

| Overall | 3.86 (0.11) | 4.40 (0.11) | −0.54 (−0.85, −0.23) |

| 3 months | 3.82 (0.13) | 4.51 (0.13) | −0.69 (−1.05, −0.33) |

| 6 months | 3.90 (0.13) | 4.28 (0.13) | −0.39 (−0.75, −0.03) |

| PEG | |||

| Time × intervention (p-value) | – | – | 0.025 |

| Overall | 6.73 (0.07) | 6.93 (0.07) | −0.19 (−0.40, 0.01) |

| 3 months | 6.39 (0.12) | 6.94 (0.12) | −0.55 (−0.88, −0.22) |

| 6 months | 6.60 (0.12) | 6.72 (0.12) | −0.13 (−0.45, 0.20) |

| PHQ-8 | |||

| Time × intervention (p-value) | – | – | 0.078 |

| Overall | 10.32 (0.18) | 10.51 (0.18) | −0.19 (−0.69, 0.32) |

| 3 months | 10.32 (0.30) | 9.94 (0.29) | 0.38 (−0.44, 1.20) |

| 6 months | 9.49 (0.30) | 10.33 (0.28) | −0.84 (−1.65, −0.03) |

| GAD-7 | |||

| Time × intervention (p-value) | – | – | 0.176 |

| Overall | 8.41 (0.19) | 8.59 (0.19) | −0.18 (−0.71, 0.34) |

| 3 months | 8.49 (0.31) | 8.24 (0.30) | 0.25 (−0.59, 1.09) |

| 6 months | 7.82 (0.31) | 8.59 (0.29) | −0.76 (−1.60, 0.07) |

| Average steps | |||

| Time × intervention (p-value) | – | – | 0.230 |

| Overall | 3651.52 (109.29) | 3416.47 (105.60) | 235.05 (−63.59, 533.69) |

| 3 months | 3884.54 (165.39) | 3394.71 (156.65) | 489.83 (41.12, 938.55) |

| 6 months | 3871.77 (171.14) | 3592.29 (156.26) | 279.48 (−177.07, 736.03) |

DISCUSSION

Racial disparities in pain and pain treatment in the USA are persistent and pervasive, but there are few interventions designed specifically for populations most impacted by these disparities.4 In the wake of the opioid crisis, there is also an urgent need for nonpharmacological pain treatment approaches.46 This trial of a novel, nonpharmacological intervention to improve chronic pain among Black patients did not produce statistically significant improvements on the primary outcome (pain-related physical functioning at 6 months) nor on all but one of the outcomes assessed at 6 months. Nonetheless, there was some evidence of benefit. The intervention was associated with more favorable changes in global impressions of pain at 6 months relative to UC, an important patient-centered outcome. Nearly all other pain-related outcome effects at 6 months were in the direction favoring the intervention and possibly clinically meaningful. For example, at 6 months, 10% more patients in the intervention had a 30% improvement in physical functioning and a greater reduction in depression symptoms (−0.84 mean difference on the PHQ-8). The intervention was also associated with lower pain intensity and interference at 3 months. Additionally, almost all participants reported that they would recommend the program to a friend with similar pain.

There are several potential reasons why our intervention did not deliver the hypothesized benefits. First, this intervention may not have been potent enough for this population of Black Veterans, whose low socioeconomic status, high burden of mental health comorbidity, and physical limitations posed significant barriers to walking and also to engaging in the 6 telephone sessions. Although our proactive outreach approach enabled us to engage a hard-to-reach population, it likely yielded more participants who were less prepared to enact behavioral change. This explanation was supported by interviews with study counselors, who viewed unmet mental health needs and barriers related to social determinants of health as major impediments to engagement. This suggests the need for more resource-intense programs for those who have high levels of mental and physical health comorbidities and fewer material resources. Finally, participants in usual care were given a pedometer and told to record their steps as well as a brochure about the benefits of walking for chronic pain, which might have slightly attenuated the differences between intervention and true usual care.

CONCLUSION

This randomized trial of a walking-focused, proactive coaching intervention for Black patients with chronic pain fills important gaps in the literature and demonstrates the feasibility of enrolling a large number of Black participants, with high levels of mental and physical health comorbidities and functional limitations, into a trial of a nonpharmacological pain treatment. Although results were promising, the intervention did not produce statistically significant improvements on the primary outcome (pain-related physical functioning over 6 months) relative to the usual care condition. More intensive efforts are likely required to address chronic pain in this population.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 47 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following people for their contribution to the study: Mariah Branson, Elizabeth Doro, Abigail Klein, Jamie Margetta, Taylor Oakley, Kimberly Stewart, Grace Polusny Thiede, and Jill Thompson.

Funding

This work was supported by a Merit Review Award (IIR no. 13-030) from the United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

American Psychosomatic Society Virtual Conference; December 3, 2020.

Society for Behavioral Medicine; April 14, 2021.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Diana J. Burgess, Email: diana.burgess@va.gov.

Emily Hagel Campbell, Email: Emily.HagelCampbell@va.gov.

Patrick Hammett, Email: Patrick.Hammett@va.gov.

Kelli D. Allen, Email: kelli.allen@va.gov.

Steven S. Fu, Email: Steven.Fu@va.gov.

Alicia Heapy, Email: Alicia.Heapy@va.gov.

Robert D. Kerns, Email: Robert.kerns@yale.edu.

Sarah L. Krein, Email: Sarah.Krein@va.gov.

Laura A. Meis, Email: Laura.Meis@va.gov.

Ann Bangerter, Email: Ann.Bangerter@va.gov.

Lee J. S. Cross, Email: Lee.Cross@va.gov.

Tam Do, Email: Tam.Do3@va.gov.

Michael Saenger, Email: Michael.Saenger@va.gov.

Brent C. Taylor, Email: Brent.Taylor2@va.gov.

References

- 1.Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2011. [PubMed]

- 2.Vadivelu N, Kai AM, Kodumudi V, Sramcik J, Kaye AD. The opioid crisis: a comprehensive overview. Current pain and headache reports. 2018;22(3):1-6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, et al. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med. 2003;4(3):277–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain. 2009;10(12):1187–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tait RC, Chibnall JT. Racial/ethnic disparities in the assessment and treatment of pain: psychosocial perspectives. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):131–41. doi: 10.1037/a0035204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janevic MR, McLaughlin SJ, Heapy AA, Thacker C, Piette JD. Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Disabling Chronic Pain: Findings From the Health and Retirement Study. J Pain. 2017;18(12):1459–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meghani SH, Polomano RC, Tait RC, Vallerand AH, Anderson KO, Gallagher RM. Advancing a national agenda to eliminate disparities in pain care: directions for health policy, education, practice, and research. Pain Med. 2012;13(1):5–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, et al. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben J, Cormack D, Harris R, Paradies Y. Racism and health service utilisation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgess DJ, van Ryn M, Crowley-Matoka M, Malat J. Understanding the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in pain treatment: insights from dual process models of stereotyping. Pain Med. 2006;7(2):119–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meints SM, Miller MM, Hirsh AT. Differences in Pain Coping Between Black and White Americans: A Meta-Analysis. J Pain. 2016;17(6):642–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen KD, Oddone EZ, Coffman CJ, Keefe FJ, Lindquist JH, Bosworth HB. Racial differences in osteoarthritis pain and function: potential explanatory factors. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(2):160–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shavers VL, Bakos A, Sheppard VB. Race, ethnicity, and pain among the U.S. adult population. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(1):177–220. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCracken LM, Matthews AK, Tang TS, Cuba SL. A comparison of blacks and whites seeking treatment for chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(3):249–55. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burgess DJ, Grill J, Noorbaloochi S, Griffin JM, Ricards J, van Ryn M, et al. The effect of perceived racial discrimination on bodily pain among older African American men. Pain Med. 2009;10(8):1341–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards RR. The association of perceived discrimination with low back pain. J Behav Med. 2008;31(5):379–89. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards M, Cunningham G. Examining the associations of perceived community racism with self-reported physical activity levels and health among older racial minority adults. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10(7):932–9. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.7.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plascak JJ, Hohl B, Barrington WE, Beresford SA. Perceived neighborhood disorder, racial-ethnic discrimination and leading risk factors for chronic disease among women: California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2013. SSM-Population Health. 2018;5:227–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallagher NA, Gretebeck KA, Robinson JC, Torres ER, Murphy SL, Martyn KK. Neighborhood factors relevant for walking in older, urban, African American adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2010;18(1):99–115. doi: 10.1123/japa.18.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong-Brown J, Eng E, Hammond WP, Zimmer C, Bowling JM. Redefining racial residential segregation and its association with physical activity among African Americans 50 years and older: a mixed methods approach. J Aging Phys Act. 2015;23(2):237–46. doi: 10.1123/japa.2013-0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu SS, van Ryn M, Nelson D, Burgess DJ, Thomas JL, Saul J, et al. Proactive tobacco treatment offering free nicotine replacement therapy and telephone counselling for socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers: a randomised clinical trial. Thorax. 2016;71(5):446–53. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu SS, van Ryn M, Sherman SE, Burgess DJ, Noorbaloochi S, Clothier B, et al. Proactive tobacco treatment and population-level cessation: a pragmatic randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):671–7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saitz R, Cheng DM, Winter M, Kim TW, Meli SM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. Chronic care management for dependence on alcohol and other drugs: the AHEAD randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(11):1156–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Connor SR, Tully MA, Ryan B, Bleakley CM, Baxter GD, Bradley JM, et al. Walking exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(4):724–34. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sitthipornvorakul E, Klinsophon T, Sihawong R, Janwantanakul P. The effects of walking intervention in patients with chronic low back pain: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018;34:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2006;38:69–119. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubak S, Sandbæk A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silva MAV, Sao-Joao TM, Brizon VC, Franco DH, Mialhe FL. Impact of implementation intentions on physical activity practice in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. PloS one. 2018;13(11):e0206294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bélanger-Gravel A, Godin G, Amireault S. A meta-analytic review of the effect of implementation intentions on physical activity. Health Psychol Rev. 2013;7(1):23–54. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhimani RH, Cross LJ, Taylor BC, Meis LA, Fu SS, Allen KD, et al. Taking ACTION to reduce pain: ACTION study rationale, design and protocol of a randomized trial of a proactive telephone-based coaching intervention for chronic musculoskeletal pain among African Americans. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1363-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Care and Education Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Institute of Medicine, Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed]

- 32.Goulet JL, Kerns RD, Bair M, Becker WC, Brennan P, Burgess DJ, et al. The musculoskeletal diagnosis cohort: examining pain and pain care among veterans. Pain. 2016;157(8):1696–703. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Wu J, Sutherland JM, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):733–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0981-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krebs EE, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Tu W, Wu J, Kroenke K. Comparative responsiveness of pain outcome measures among primary care patients with musculoskeletal pain. Med Care. 2010;48(11):1007–14. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181eaf835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40(9):771–81. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark L, Fairhurst C, Torgerson DJ. Allocation concealment in randomised controlled trials: are we getting better? BMJ. 2016;355:i5663. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savovic J, Jones HE, Altman DG, Harris RJ, Juni P, Pildal J, et al. Influence of reported study design characteristics on intervention effect estimates from randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(6):429–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-6-201209180-00537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krein SL, Metreger T, Kadri R, Hughes M, Kerr EA, Piette JD, et al. Veterans walk to beat back pain: study rationale, design and protocol of a randomized trial of a pedometer-based internet mediated intervention for patients with chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:205. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113(1-2):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(2):105–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dobscha SK, Corson K, Perrin NA, Hanson GC, Leibowitz RQ, Doak MN, et al. Collaborative care for chronic pain in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(12):1242–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–59. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fischer D, Stewart AL, Bloch DA, Lorig K, Laurent D, Holman H. Capturing the patient's view of change as a clinical outcome measure. JAMA. 1999;282(12):1157–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.12.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ibrahim JG, Lipsitz SR. Parameter estimation from incomplete data in binomial regression when the missing data mechanism is nonignorable. Biometrics. 1996;52(3):1071–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1-3):163–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee. National pain strategy: a comprehensive population health level strategy for pain. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2016

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 47 kb)