INTRODUCTION

Under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, drug manufacturers ordinarily pay a rebate to Medicaid for price increases exceeding inflation. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) established a special Medicaid rebate for line extensions of brand-name drugs starting in January 1, 2010.1 This provision of the ACA aimed to close a loophole that would enable drug manufacturers to avoid paying inflation-linked discounts to Medicaid by introducing new formulations or minor changes to existing drugs. However, line extensions were not subsequently defined through rulemaking; manufacturers were therefore to use “reasonable assumptions” and self-report line extension status. Consequently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) noted that manufacturers may not be adequately self-reporting their products as line extensions, which could result in underpayment of required rebates.2 In response, CMS issued a regulation (finalized in December 2020) to formally define line extensions and improve reporting.2,3 In this study, we sought to examine trends in reimbursement of line extension drugs in Medicaid since passage of the ACA and estimate rebates for line extensions under CMS’ line extension rule.

METHODS

We extracted data on gross drug expenditures, prescriptions, launch date, product family, and formulation information from Medicaid’s drug utilization data files4 and SSR Health5 for brand-name drugs from Q2 2010 (post-ACA) to Q4 2018. This merged dataset covered approximately 95% of Medicaid brand-name drug spending in 2018. We excluded drugs initially launched without an oral form and certain abuse-deterrent formulations, as these are not subject to the line extension policy. Under CMS’s rule, line extensions include modified-release drugs (e.g., extended-release formulations) and changes in dosage form, strength, and route of administration, including new oral and non-oral formulations. Consistent with CMS’ definition, we identified line extension drugs launched after the initial marketing date of the original product. Finally, to estimate the potential savings from applying the higher rebate level under the rule, we compared the estimated total Medicaid rebate (basic and additional inflation-linked rebates) in 2018 with and without the line extension rebate for line extension drugs as classified under the proposed regulation.6

RESULTS

The study included 3103 brand-name drugs with total Medicaid expenditures in 2018 of $21.4 billion, of which 1038 (33.5%) drugs would qualify as line extensions under CMS’ new rule. Over one-third (376, 36.2%) line extension drugs were extended and other modified-release formulations, 562 (54.1%) were other new oral formulations, and 100 (9.6%) were new non-oral formulations.

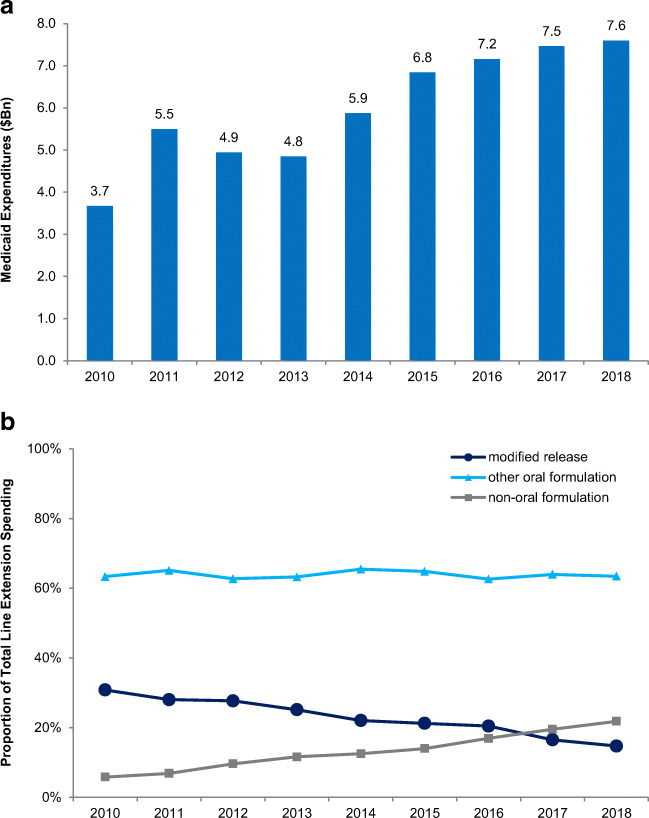

Total Medicaid spending on line extension drugs increased from $3.7 billion in 2010 to $7.6 billion in 2018. The top 10 product families accounted for 65% of total line extension spending in 2018 (Table 1). Although spending on modified-release formulations was stable ($1.1 billion in 2010 to $1.1 billion in 2018), the proportion of line extension spending on new non-oral formulations (such as injectable reformulations) increased from 6 to 22% ($213 million to $1.7 billion) (Fig. 1). The estimated potential savings from higher rebates under CMS’ rule would have accounted for 9.6% of pre-rebate line extension spending in 2018.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Selected Top Product Families by Medicaid Expenditures on Line Extensions

| Brand name | Generic name | Line extensions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type(s) | 2018 spend ($M)* | |||

| Invega/Invega Sustenna | Paliperidone | 10 | Non-oral formulations, modified-release form | 1059.8 |

| Suboxone/Suboxone Film | Buprenorphine/naloxone | 8 | Other oral formulations | 759.7 |

| Latuda | Lurasidone | 5 | Other oral formulations | 586.6 |

| Abilify/Abilify Maintena | Aripiprazole | 19 | Non-oral formulations, other oral formulations | 519.5 |

| Vyvanse | Lisdexamfetamine | 10 | Other oral formulations | 478.6 |

| Onfi | Clobazam | 3 | Other oral formulations | 379.1 |

| Ritalin | Methylphenidate | 16 | Modified-release forms | 348.3 |

| Prezista | Darunavir | 6 | Other oral formulations | 320.9 |

| Xarelto | Rivaroxaban | 12 | Other oral formulations | 264.2 |

| Xifaxan | Rifaximin | 3 | Other oral formulations | 203.7 |

Notes: NDC national drug code. *2018 gross Medicaid expenditures in millions of US dollars

Figure 1.

a, b Trend in gross Medicaid expenditures on line extension drugs, 2010–2018. Notes: Line extensions included modified-release drugs (e.g., extended-release formulations), other new oral formulations, and non-oral formulations.

DISCUSSION

In the decade after the ACA’s enactment, Medicaid expenditures on line extension drugs doubled, with nearly two-thirds of total line extension spending concentrated in the top 10 product families. In 2018, gross Medicaid spending on line extension drugs would have been an estimated 9.6% lower if line extension rebates had been applied as under CMS’ rule. Limitations were that information was not available for roughly 5% of Medicaid brand-name drug spending, and best-price and state supplemental rebates were not included as they are confidential. Additionally, this study estimated possible savings from the most recent study year under CMS’ regulation; future savings from this policy may be affected by changes in drug mix, rate of new line extension introduction, and other manufacturer behavior.

The line extension loophole has allowed manufacturers to evade paying rebates ordinarily due to Medicaid when drug prices increase faster than inflation. CMS’ final regulation codifying a definition of line extension drugs will be effective starting in January 1, 2022—over a decade after passage of the relevant provision in the ACA. The regulatory challenges associated with implementing this policy can help inform ongoing policymaking around expanding inflation-linked rebates, as is being currently considered by Congress.

Funding

Dr. Kesselheim was supported by Arnold Ventures. The author’s funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Since submission of this work, Dr. Kesselheim reports serving as an expert witness for a class of plaintiffs in a case against Gilead related to tenofovir. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Section 2501(d). Enacted March 23, 2010. Pub. L. 111-148. Subsequently amended by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (Pub. L. 111-152, 2010) and Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (Pub. L. 115-123. 2018).

- 2.Federal Register. Proposed rule by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid Program; Establishing Minimum Standards in Medicaid State Drug Utilization Review (DUR) and Supporting Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) for Drugs Covered in Medicaid, Revising Medicaid Drug Rebate and Third Party Liability (TPL) Requirements. 85 FR 37286. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-06-19/pdf/2020-12970.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- 3.Federal Register. Final rule by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid Program; Establishing Minimum Standards in Medicaid State Drug Utilization Review (DUR) and Supporting Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) for Drugs Covered in Medicaid, Revising Medicaid Drug Rebate and Third Party Liability (TPL) Requirements. 85 FR 87000. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-12-31/pdf/2020-28567.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- 4.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/medicaid-drug-rebate-program/index.html. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- 5.US Prescription Brand Net Pricing Data and Analysis. SSR Health website. https://www.ssrhealth.com. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- 6.Hwang TJ, Kesselheim AS. Public referendum on drug prices in the US. BMJ. 2016;355:i5657. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]