Abstract

Objectives:

The purpose of this systematic review was to synthesize research examining the cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between sleep and healthy aging in late-life.

Methods:

A systematic search was conducted via both PubMed and PsychINFO databases using terms related to “sleep” and “healthy aging.” Studies which examined the association between healthy aging and one or more sleep parameters were included in the present review.

Results:

Fourteen relevant studies, nine cross-sectional and five longitudinal, were identified. Overall, cross-sectional studies revealed that positive indicators of sleep were generally associated with a greater likelihood of healthy aging. In contrast, the limited number of existing longitudinal studies revealed mixed and inconclusive results.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that adequate sleep is more likely to coincide with relevant markers of healthy aging in late-life and underscores the need for additional research investigating the longitudinal associations between sleep and healthy aging.

Clinical Implications:

Healthy sleep, consisting of moderate sleep duration and good quality, shows promise for the promotion of healthy aging. Consequently, poor sleep should be identified and intervened upon when necessary.

Keywords: sleep, insomnia, successful aging

Introduction

Older adults represent one of the fastest growing demographic groups, with the percentage of older adults estimated to increase from 8.5% to 17% of the world population by 2050 (He et al., 2016). While health-related research efforts have historically focused on understanding the unique predictors of chronic illnesses and diseases, an understanding of the factors which influence the aging process more broadly is equally necessary. Specifically, identifying modifiable health behaviors which impact healthy aging may allow for preventative interventions that not only delay the onset of illness and disability but also promote healthy physical, psychological, cognitive, and social functioning in late-life.

Healthy Aging

While aging may predispose individuals to the onset of chronic health conditions, aging is not in and of itself a cause of disease (Rattan, 2014). In fact, between 3.3 and 35.3% of older adults are considered “successful agers” and maintain high levels of well-being in their later years (McLaughlin et al., 2012). That is, a small but robust portion of older adults appear to be resistant to the physical, cognitive, and social declines that are commonly seen among older adults.

Although no universal definition of healthy aging exists, one theoretical model has gained significant attention since its inception. Rowe and Kahn’s (1997) tripartite model of successful aging characterizes healthy aging as the combination of three interdependent elements: the absence of disease and disability, maintenance of high cognitive and physical functioning, and active engagement with life. This model has not been without criticism (Calasanti & King, 2021; Martinson & Berridge 2015). Some researchers have called for more inclusive definitions of healthy aging which would consider historical, cultural and cultural factors, as well as arguments that healthy aging is possible even in the presence of well-managed health conditions (Calasanti & King, 2021; Martinson & Berridge 2015). While Rowe and Kahn’s model remains one of the most widely used theoretical models of healthy aging, research has slowly moved away from their rigid conceptualization of healthy aging with more recent work sometimes adding or eliminating one or more domains of Rowe and Kahn’s original model.

Meta-analyses have already identified a number of key health factors prospectively associated with healthy aging, including smoking abstinence, higher amounts of physical activity, lower body mass index, and lower alcohol use (Peel et al., 2005; Pruchno & Wilson-Genderson, 2012). However, relatively little research has examined the association between sleep and healthy aging despite considerable evidence that sleep has relevant implications for each individual domain of Rowe and Kahn’s (1997) tripartite model.

Sleep

Older adults are well-known to experience age-related physiological declines in sleep, as well as higher rates of sleep disorders (Ohayon et al., 2004). These sleep-related changes are associated with physical, psychological, and social-related consequences. For example, poor sleep is linked with a range of chronic health conditions including heart disease, chronic pain, diabetes, and lung disease, as well as mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety (Foley et al., 2004; Zhai et al., 2015). Shorter and more fragmented sleep has also been linked with cognitive impairment in late-life including an increased risk of dementia (Dzierzewski, Dautovich, & Ravyts, 2018). Finally, poor sleep is associated with decreased social engagement and reduced participation in valued activities among older adults (Chen et al., 2016; Owusu et al., 2018).

While poor sleep has been linked with reduced life expectancy, adequate sleep is common among individuals living well into late-life. For example, although a meta-analysis of population-based studies found that poor sleep prospectively predicts mortality (Cappuccio et al., 2010), a study of centenarians found that over 57% reported good sleep quality, a higher rate than those previously reported among younger older adult samples in poor health (Tafaro et al., 2007). While these findings suggest that healthy sleep may confer a positive benefit to well-being in late-life, comprehensive reviews examining sleep and healthy aging are lacking.

Present Study

The purpose of this systematic review was to synthesize existing literature examining the association between sleep and healthy aging. Specifically, the present study sought to investigate the cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between sleep and healthy aging in older adult populations, as well as explore the relative quality of sleep among healthily aging individuals. Moreover, as part of this aim, the review sought to identify whether certain facets of sleep are differentially associated with healthy aging. Finally, the present review sought to quantitatively synthesize the effect sizes of the cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between sleep and healthy aging.

Methods

Study Search Procedure

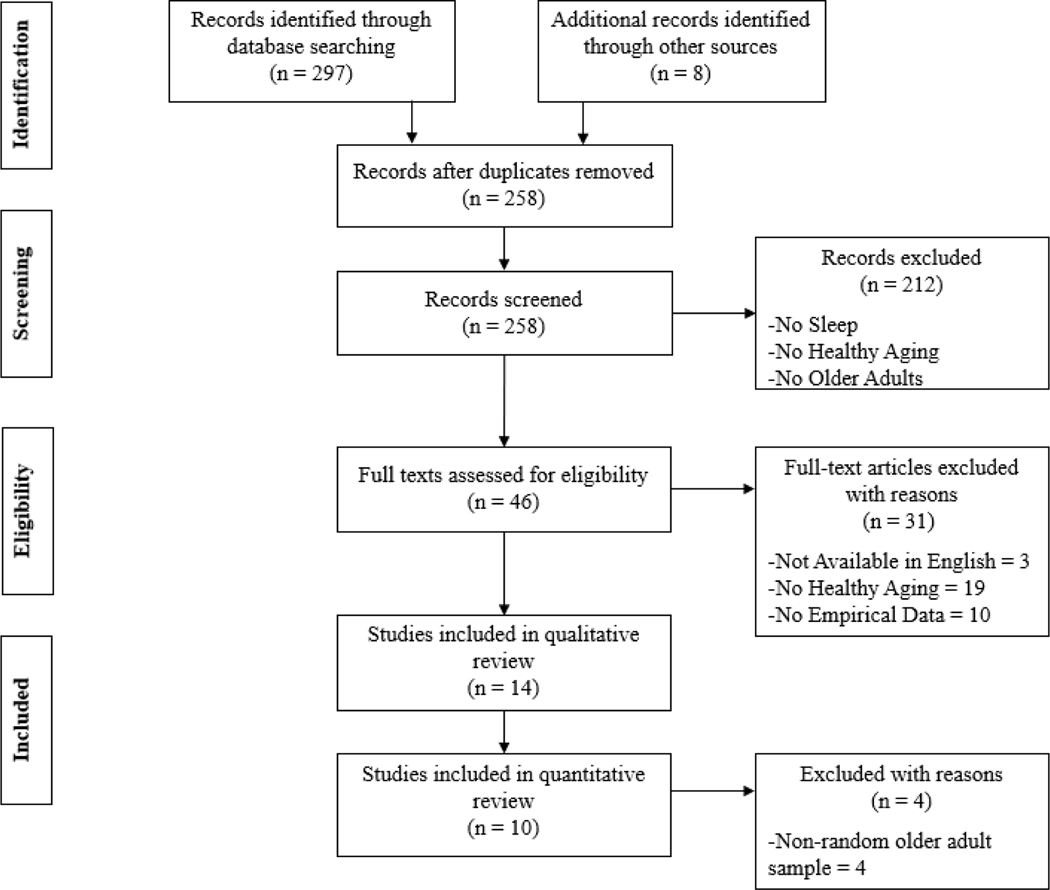

This systematic review was conducted and reported following PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Prisma Group, 2009). Relevant studies for this review were identified via two major scientific publication databases: PubMed and PsycINFO. Searches included terms to identify samples examining healthy aging (e.g., “healthy aging”, “resilient aging”, “optimal aging”) and terms to identify the examination of sleep-related factors (e.g., “sleep”, “insomnia”, “sleep wake disorders”).

These initial search criteria were completed in February 2019 and yielded 297 studies. The titles and abstracts of these studies were subsequently independently evaluated by both authors to assess their appropriateness for the current review. Articles which included a term related to sleep or healthy/successful/optimal/resilient aging in either the title or abstract were assessed via a full-text review. References from pertinent articles were also reviewed to identify additional studies that may have been missed from the initial search.

Study Inclusion Criteria

Studies included in this review were limited to peer-reviewed articles that met the following criteria: 1) included quantitative analyses, 2) sampled adults over age 60, 3) included individuals considered to have healthily aged, with healthy aging being explicitly defined and measured, 4) assessed one or more aspects of sleep (e.g., insomnia, sleep duration, etc.), and 5) were available in English. The age cut-off of 60 was chosen in order to be consistent with the UN definition of older adults (Dugarova, 2017). Due to the variability in which healthy aging has been assessed, no constraints were placed on how healthy aging was measured. No exclusion criteria were applied. Studies were independently examined by both authors to assess whether they met study criteria. The flow diagram resulting in the articles included in this review is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature review search for studies examining sleep and healthy aging

Quality Assessment

The Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies developed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was used to assess the quality of studies included in this review (NIH, 2014). This 14-item assessment tool includes a transparent checklist of both study design indicators and potential sources of bias.

Quantitative Evaluation

The quantitative synthesis portion of this review was restricted to studies which examined sleep and the likelihood of healthy aging among randomly sampled older adults (N = 10). Odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval were the most common metric in which sleep and healthy aging were examined. As result, OR were used as the comparison metric among studies except when adjusted odds ratio (AOR), or odds ratio that accounted for potential confounders, were provided in the results. If studies included different summary measures (e.g., Chi-squared tests), then these measures were transformed into the appropriate metric using established statistical methods (Borenstein et al., 2009).

Results

Fourteen studies met the aforementioned inclusion criteria. Studies were published between 1994 and 2016 with ten of the studies consisting of secondary data analyses. Of the fourteen studies, nine were cross-sectional and five were longitudinal. The location of the studies varied widely with studies being conducted in four continents.

The assessment of healthy aging differed considerably among the studies, with some using an extensive combination of objective and subjective measures of health and well-being and others relying solely on a few self-report measures. While measures of disease and disability, as well as indicators of physical and cognitive functioning were nearly ubiquitous, few studies included measures of social functioning to assess older adults’ engagement in life. Variability in the prevalence of healthy aging was also pronounced among studies randomly sampling from older adult populations, with the number of participants meeting study criteria for healthy aging ranging from 10.81 to 64.6% (M= 30.94, SD= 18.02). Key study characteristics and major relevant findings from each study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies examining the association between sleep and healthy aging.

| Authors | Sample | Study Design | Sleep Measure(s) | Healthy Aging Criteria | Major Relevant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Andrews et al., 2002 | 1947 Australian older adults (Age ≥ 70; 44.54 % female) | Cross-Sectional | Self-reported rating of sufficient sleep (Yes / No) | 1) No cognitive impairment on MMSE, 2) score of 3/5 on delayed recall of task, 3) no disability of 7 tasks of daily living, 4) no more than 1 disability in 8 activities of physical performance or gross mobility, 5) able to hold a semi-tandem for 10 seconds, & 6) able to stand from a seated position 5 times in 20 seconds | Self-reported sufficient levels of sleep differentiated high versus low levels of healthy aging but not high versus intermediate levels |

| Cernin et al., 2011 | 67 African American older adults (M age = 73; 82.1% female) | Cross-Sectional | PSQI | 1) Able to hold a tandem balance for 10 seconds, 2) able to complete 5 chair stands in 20 seconds, 3) maximum of one IADL disability, 4) score of 24 ≥ on the MMSE & 5) 10 ≥ on Animal Naming | Sleep was associated with subjective but not objective measures of healthy aging |

| Crawford-Achour et al., 2014 | 171 French older adults (M age = 73.2; 53.8% female) | Cross-Sectional | PSQI & Polysomnography | Self-reported perceived health status from 0 to 10; Self-reported life satisfaction from 0 to 10 | Sleep quality was positively associated perceived health status and life satisfaction |

| Driscoll et al., 2008 | 64 Healthily aging older adults (M age = 79; 46.9% female) | Cross-Sectional | PSQI, Polysomnography | 1) Absence of current or past psychiatric or sleep disorder, 2) absence of serious or uncontrolled physical health problems or medication use which interferes with sleep or mood, 4) HDRS < 7, 5) MMSE ≥ 24, & 6) SOL < 6 min on MSLT | Better sleep quality was associated with higher physical health–related quality of life and mental health-related quality of life in healthily aging older adults |

| Hoch et al., 1994 | 50 Healthily aging older adults (M age = 74.6; 58% female) | Longitudinal | PSQI, Polysomnography, Self-reported Sleep Diaries | 1) Absence of present or past psychiatric disorders as assessed by the SADS-L, 2) HDS > 7, 3) MMSE ≥ 27, 4) absence of past or present neurological or physical condition, or medications affecting mood or sleep | Sleep remained stable over 2 years, with age, cognitive status, and medical burden predicting decays in sleep efficiency |

| Hoch et al., 1997 | 50 Healthily aging older adults (M age = 75.7; 54% female) | Longitudinal | PSQI & Polysomnography | 1) Absence of present or past psychiatric disorders as assessed by the SADS-L, 2) HDS > 7, 3) MMSE ≥ 27, 4) absence of past or present neurological or physical condition, or medications affecting mood or sleep | “Old old” participants, but not “young old” participants, showed declines in subjective and objective sleep parameters over time |

| Hsu et al., 2017 | 1977 older adults(M age = NR, all participants ≥ 62; 39.5% female) | Longitudinal | Self-reported sleeping well (yes/no) | 1) Ability to complete ADL independently; 2) absence of depressive symptoms (CEDS < 10), 3) absence of cognitive impairment (age-appropriate SPMSQ) & 4) able to provide social support to others | Sleeping well at baseline was associated with a greater likelihood of being classified as a healthy aging octogenarian 12–14 years later |

| Kendig et al., 2014 | 978 Australian older adults (M age = 73.4; 53% female) | Longitudinal | Self-reported restful sleep (4 point Likert-scale) | 1) Community-dwelling status, 2) self-rated health ranging from good to excellent, 3) ability to complete IADL independently, & 4) ≥ 18 on a positive affect measure | Restless sleep was negatively associated with healthy aging cross-sectionally but not at a 12-year follow-up |

| Li et al., 2006 | 1516 Chinese older adults (M age = 72.67; 52.9% female) | Cross-Sectional | Self-reported sleep duration | 1) Total score on the MMSE ≥ 4 points above educational cut-off, 2) ADL score ≤ 15, 3) self-reported mood in the “excellent” to “good” range, & 4) absence of physical disabilities | Sleeping 7–8 hours a day was positively associated with healthy aging after controlling for age and gender |

| Li et al., 2014 | 903 Taiwanese older adults (M age = 73.9, 47 % female) | Cross-Sectional | Self-reported history of sleep disorder (yes / no) | SF-36 Physical Component Summary > 53 and Mental Component Summary Score > 59 | Older adults categorized as healthy agers where less likely to have a history of sleep disorder compared to their normal aging peers |

| Liu et al., 2016 | 5616 Chinese older adults (M age = 68; % female NR) | Cross-Sectional | Self-reported sleep duration & quality | 1) Absence of major diseases (e.g., cancer, diabetes), 2) CESD-10 < 10, 3) no self-reported difficulty completing ADLs, 4) TICS ≥ median, 5) no self-reported difficulty with IADL, 6) self-reported social activity (e.g., volunteering) in the past month | Short (< 6 hours) and long sleep duration (≥ 9 hours), as well as poor sleep quality negatively predicted healthy aging |

| Ng et al., 2009 | 1,281 Chinese older adults (M age = 72.1; 60% female) | Cross-Sectional | Self-reported good sleep (never / sometimes / often) | 1) Independent on IADL, 2) good or excellent self-reported health, 3) MMSE ≥ 26, 4) GDS < 5, 5) 1 ≥ self-reported social or productive activity a week, 6) Life Satisfaction Scale < 11 | Self-reported good sleep did not differ between healthy and normal agers |

| Shi et al., 2016 | 2296 Chinese older adults (M age = NR, all participants ≥ 65, 56.14% female) | Cross-Sectional | Self-reported sleep quality and duration | 3 of the following 5 criteria: 1) Self-reported health as good or excellent, 2) Self-reported psychological status or mood as “good”, 3) MMSE ≥ 24, 4) Able to complete six ADLs independently, 5) Able to regularly walk continuously for 1 km, lift a 5 kg weight, or able to squat three consecutive times. | Better sleep quality was associated with higher odds of healthy aging |

| Spiegel et al., 1999 | 57 Swiss older adults (M age = 63.5; 40.3% female) | Longitudinal | Polysomnography | Measure 1: Being willing and physically able to participate in follow-up versus being unable to participate due to reasons of health Measure 2: Cognitive performance on the vocabulary subtest of the WAIS, the MMSE, and ERFC |

Several sleep parameters (REM sleep latency, REM density and non-REM shifts) predicted cognitive decline 14 years after baseline but not mortality |

Notes: ADL = Activities of Daily Living, CESD-10 = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, ERFC = Rapid Evaluation of Cognitive Functioning, GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale, HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, MMSE = Mini Mental Status Exam, Multiple Sleep Latency Test = MSLT, PSQI = Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index, NR = Not reported, SADS-L = Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, lifetime version, SF-36 = 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, SOL = Sleep Onset Latency, SPMSQ = Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire, TICS = Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status, WAIS = Wechsler Adult Intelligence

Quality Assessment

Use of the NIH quality assessment tool showed considerable variability among studies, with the number of quality indicators ranging from 6 to 11 out of possible total of 14 (M = 8.07, SD = 1.44). Quality differed across study designs, with cross-sectional designs obtaining a mean quality rating of 7.22 (SD = .67), while longitudinal designs obtained a mean score of 9.60 (SD = .51). The complete quality assessment for each study can be found in the online supplement.

Quantitative Synthesis

Overall, among the studies using randomly sampled older adults, ten out of a possible twelve indicators of sleep showed a significant positive association between sleep and healthy aging. That is, better sleep was generally associated with a greater likelihood of healthy aging. For example, symptoms of poor sleep, such as short sleep duration or poor sleep quality were associated with a lower likelihood of having aged well. In contrast, indicators of adequate sleep, such as obtaining 7–8 hours of sleep or not having a history of a sleeping disorder, were associated with a greater likelihood of healthy aging. While these results were fairly consistent among cross-sectional studies, findings pertaining to the longitudinal association between sleep and healthy aging were limited and mixed. For example, while one study found that sleeping well at baseline predicted a greater likelihood of healthy aging in the future (Hsu et al., 2017), another study found no association between restful sleep and one’s likelihood of having aged healthily (Kendig et al., 2014). Taken together, the included studies’ odds ratio suggest a small to medium effect size for sleep as a predictor of healthy aging among cross-sectional studies (Chen, Cohen, & Chen, 2010). See Figure 2 for a forest plot of the associations between sleep and healthy aging.

Figure 2.

Forest Plot of the Odds Ratio Between Sleep and Healthy Aging in Studies Randomly Sampling Among Older Adults.

Notes. aOdds ratio when healthy aging conceptualized as life satisfaction, bOdds ratio when healthy aging conceptualized as perceived health status, cOdds ratio between restful sleep and the likelihood of not aging healthily at baseline; statistical data for longitudinal association between sleep and healthy aging, which failed to reach statistical significance, was not provided and therefore could not be included in the plot.

Qualitative Synthesis of Cross-Sectional Studies

Seven out of the nine cross-sectional studies found an association between one or more sleep parameters and the likelihood of healthily aging. Of all the studies, only one exclusively examined the relationship between sleep and healthy aging in a random sample of older adults (Liu et al., 2016). In their cross-sectional study of Chinese older adults, Liu et al. (2016) found an inverse U-shape relationship between nighttime sleep duration and healthy aging likelihood, with older adults sleeping 7 hours having the greatest likelihood of having aged healthily compared to those with very short (<6 hours) or very long (>9 hours) sleep durations. Older adults who reported experiencing poor sleep quality five to seven times a week were also significantly less likely to be classified as having healthily aged compared to individuals who reported poor sleep quality less than once a week. These findings are corroborated by two other cross-sectional studies (Li et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2016). In another study of Chinese older adults, individuals classified as having healthily aged were more likely to report moderate sleep duration (6–9 hours) and “good” to “very good” sleep quality compared to those not classified as having aged healthily (Shi et al., 2016). Finally, an additional study of Chinese older adults found that participants who obtained between 7–8 hours of sleep a night were significantly more likely than their peers, who either slept over 8 hours or under 7 hours, to be considered as aging healthily (Li et al., 2006). These findings remained significant even after controlling for age and gender.

One study examined the cross-sectional association between sleep duration and healthy aging among Australian older adults, with healthy aging operationalized as a categorical variable (e.g., high, intermediate, or low). Participants who self-reported obtaining “sufficient sleep” were more likely to be categorized as having obtained high rather than low levels of healthy aging (Andrews et al., 2002). However, participants categorized as having either high or intermediate levels of healthy aging did not differ in their self-reported ability to obtain sufficient levels of sleep.

The cross-sectional association between sleep and healthy aging may extend beyond sleep duration and quality. For example, healthily aging Taiwanese older adults were significantly less likely to endorse having a sleep disorder history (e.g., insomnia, sleep apnea) compared to their normal aging peers (Li et al., 2014).

Two studies specifically sought to examine the association between sleep and perceived health, with perceived health serving as a proxy of healthy aging. Among a sample of French older adults, higher self-reported sleep quality predicted both participants’ perceived health status and their life satisfaction (Crawford-Achour et al., 2014). Another study examined the sleep of healthily aging older adults over the age of 75 in the United States (Driscoll et al., 2008). Among these participants, self-reported and diary-based measures of sleep revealed high levels of nocturnal sleep quality and daytime alertness. Additionally, better sleep quality was associated with higher self-reported physical and mental-health related quality of life.

Two of the included studies failed to find a cross-sectional association between sleep and healthy aging. In the first study, Chinese individuals who self-reported obtaining “good sleep”, either “once a month or more but less than once a week” or “once a week or more”, did not differ in their likelihood of having healthily aged compared to those who reported obtaining “good sleep” less than once a month (Ng et al., 2009). Another study consisting of a small sample of African Americans similarly found that self-reported sleep quality over the past month was not associated with healthy aging (Cernin et al., 2011).

Qualitative Synthesis of Longitudinal Studies

Four out of the five studies which examined the longitudinal association between sleep and healthy aging found at least partial support for a positive association between sleep and healthy aging. Two studies explicitly sought to examine whether sleep and other health variables at baseline significantly predicted healthy aging status at follow-up. For example, in a study of Taiwanese older adults, self-reported “sleeping well” at baseline was found to be positively associated with the likelihood of having healthily aged as an octogenarian 14–18 years later (Hsu et al., 2017). Similarly, Kendig et al. (2014) examined the association between self-reported restful sleep at baseline, operationalized as the degree to which participants felt rested in the morning upon awakening, and the likelihood of healthy aging at a 12-year follow-up. Despite a significant association between sleep and healthy aging at baseline, restful sleep failed to prospectively predict healthy aging.

Three studies examined changes in sleep parameters among older adults classified as having aged healthily at baseline. In one study, healthily aging older adults’ sleep, measured at multiple assessments over the span of two years, remained largely stable over time (Hoch et al., 1994). Specifically, the percentage of time that participants spent in rapid eye movement (REM) and slow-wave sleep did not significantly decrease, nor did diary-based measures of sleep duration. A second study by the same research team found that, among healthily aging older adults, sleep declined for the “old old” but not the “young old” (Hoch et al., 1997). A third study examined changes in sleep among a group of healthy Swiss older adults at baseline and at a 14 year follow-up (Spiegel et al., 1999). It was found that none of the fourteen polysomnographic sleep parameters differentiated survivors from non-survivors at a 14-year follow-up.

Discussion

Studies included in the present review suggest the possibility of a cross-sectional association between sleep and healthy aging. That is, with some exceptions, older adults classified as having aged healthily were more likely to report better sleep including higher sleep quality, moderate amounts of sleep duration, and the absence of a sleep disorder history. In contrast, the limited findings regarding the longitudinal influence of sleep as a predictor of healthy aging are inconclusive and warrant further research.

Cross-Sectional Studies

The cross-sectional findings between sleep and healthy aging extends previous research by suggesting that adequate sleep is not only associated with a reduction in illness and disability as previously suggested (Cappuccio et al., 2010; Ranjbaran et al., 2007), but may also be linked with high concurrent physical and cognitive performance. Said another way, older adults with adequate sleep health appear to be more likely to experience concurrent positive healthy aging outcomes than their counterparts who experience poor sleep.

Despite the majority of cross-sectional studies suggesting a link between sleep and healthy aging, two studies found no evidence of such an association. Several potential factors may explain the failure to observe the expected finding. First, though Ng et al. (2009) found no association between “good sleep” and the likelihood of successful aging, their operationalization of “good sleep” differs substantially from well-established self-report measures. Specifically, their analyses categorized participants who reported “sometimes” experiencing good sleep as good sleepers even though this meant that they only experienced “good sleep” one to three times a month. This categorization may have inadvertently grouped individuals who would have traditionally been identified as having some sleep disturbance by most commonly used self-report measures with individuals able to attain adequate sleep on a more consistent basis.

The second cross-sectional study which failed to find an association between sleep and healthy aging also had several constraints (Cernin et al., 2011). First, in contrast to other studies included in this review, the relatively small sample size (n=67) may have reduced statistical power and limited the ability to detect an effect. Secondly, this study was the only one to exclusively examine a racial minority group in the United States, suggesting that race may modify the strength of the relationship between sleep and healthy aging. Existing racial disparities in healthcare often result in the earlier onset and increased prevalence of chronic health conditions among minorities populations in the United States (Assari, Moazen-Zadeh, et al., 2017). Thus, the presence of adequate sleep and healthy aging outcomes may be less common among minority populations faced with taxing medical and psychological complications earlier in life (Assari et al., 2017).

Longitudinal Studies

The mixed results and limited number of longitudinal studies preclude definitive conclusions about the temporal association between sleep and healthy aging. On one hand, findings such as those by Kendig et al. (2014), which suggest that sleep does not prospectively predict healthy aging, aligns with past research examining sleep and chronic disease in late-life. For example, a nationally representative study of community-dwelling older adults found that over 83% of participants reported having at least one chronic medical condition, with the presence of medical conditions being independently associated with one or more sleep problems (Foley, Ancoli-Israel, Britz, & Walsh, 2004). These findings suggest that sleep disturbance in older adults may occur, not as a direct result of the aging process, but rather as a consequence of medical comorbidities. Additional research has corroborated these results, identifying physical illness as a consistent risk factor in the onset sleep disturbance in late-life (Smagula et al., 2016).

On the other hand, the aforementioned research on sleep and health contrasts with established knowledge on the role of poor sleep in exacerbation of several prominent chronic health conditions in older adults, such as diabetes, cancer, or cardiovascular disease (Gangwisch et al., 2007; Meisinger et al., 2007; Ranjbaran et al., 2007). One possible explanation may be the presence of a bidirectional relationship whereby sleep disturbance impedes future healthy aging and lower rates of healthy aging interfere with older adults’ long-term sleep. Further research is needed to reconcile these discrepant findings and disentangle the temporal associations between sleep and healthy aging.

The longitudinal examination of sleep and healthy aging in the literature is currently obfuscated by the use of a limited number of sleep parameters, several of which may be closely linked with the other health factors. For example, the examination of restful sleep by Kendig et al. (2014) and its relation to healthy aging may be confounded by the presence of health conditions such as depression or chronic pain, both which have previously been shown to significantly alter one’s perception of sleep (Martin et al., 2014).

Finally, the examination of sleep among healthily aging older adults sheds light on the relative stability of sleep among healthy agers. In contrast to the sleep disturbance found among most community-dwelling older adults (Ohayon et al., 2004), there is some evidence to suggest that sleep in healthily aging older adults appears to be more robust and resistant to change (Hoch et al., 1994). A second preliminary finding is that the association between sleep and health appears even among healthily aging older adults, indicating that relatively minor differences in health may influence sleep or vice versa.

Potential Moderating Factors

Although preliminary, some evidence suggests that age and sex may moderate the relationship between sleep and healthy aging (e.g., Liu et al., 2016). The stronger association between sleep and healthy aging among women than men is somewhat paradoxical. Compared to their same-age male peers, older adult women endorse experiencing poorer subjective sleep (van den Berg et al., 2009). Yet, women are known to have longer life expectancies (Austad & Fischer, 2016).

One possible explanation for these divergent findings is the male-female health paradox which suggests that while women may have longer life expectancies, they experience higher rates of disability and poor health in late-life compared to men (Alberts et al., 2014). Differences in sex hormones have been posited as an underlying cause of the male-female health paradox and have also been hypothesized to explain sex differences in the association between sleep and mortality (Beydoun et al., 2017). Further research into the role of sex hormones, as well as other potential factors which may explain sex differences in the relationship between sleep and healthy aging are warranted.

Similar to the effect of sex, increased age is associated with well-known declines in several important sleep parameters including decreases in sleep duration and efficiency (Ohayon et al., 2004). Given the cross-sectional associations between sleep and health (Foley, Ancoli-Israel, Britz, & Walsh, 2004), the ability to obtain adequate sleep with increasing age may suggest better concurrent overall health and a greater likelihood of experiencing positive aging outcomes. That is, older adults who are resistant to the age-related declines in sleep might also be more resistant to traditional decreases in physical, cognitive, and social functioning, as well as the onset of illness and disability.

Methodological Limitations

Several methodological shortcomings of the existing literature are noteworthy. The predominance of sleep as a dichotomous variable among many of the research studies is one of the most significant limitations. The decision to dichotomize sleep (e.g., restful sleep, good sleep, sleeping well) prevents the evaluation of dose-response relationships between sleep and healthy aging. Additionally, researchers should carefully consider the possibility of an inverse U-shaped association between sleep and aging such that very short and very long sleep durations are each negatively associated with healthy aging.

An additional limitation of using dichotomized variables for sleep is that it relies on arbitrary cut-off points. However, some sleep recommendations, such as sleep duration, are expressed as a range and may vary depending on one’s age or other contextual factors. For example, sleep duration recommendations established by the National Sleep Foundation suggest that adults over the age of 65 obtain between 7 and 8 hours of sleep, however, in some cases 5–6 hours or 9 hours may also be appropriate (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015) The inconsistent operalization of what qualifies as moderate sleep duration is another limitation of the existing research. Future studies would benefit from using well-established cut-offs such as those established by the National Sleep Foundation.

The lack of repeated measurements of sleep over time is a second major limitation of the existing literature. The use of a single self-reported item to retrospectively assess an individual’s sleep may be particularly susceptible to recall bias and thus may inaccurately assess sleep in late-life. Additionally, the use single time-point assessments may fail to capture the well-known night-to-night fluctuations that occur with sleep (Buysse et al., 2010).

Finally, the inconsistent operalization of healthy aging represents another significant limitation. Few of the reviewed studies measured all three domains of Rowe and Khan’s successful aging model, yet, alternative theoretical models of healthy aging were lacking. Additionally, studies primarily relied on self-report measures when assessing aspects of healthy aging suggesting that additional objective measures are warranted.

Future Directions

Three avenues for research seeking to further elucidate the relationship between sleep and healthy aging are proposed. First, the relationship between sleep and healthy aging has, to date, been primarily limited to studies which dichotomously quantify sleep and healthy aging. On one hand, an overly restrictive operationalization of healthy aging may result in a scenario where older adults with inconsequential health concerns and high functioning are categorized as being in the same group as individuals with serious and chronic health concerns and low levels of functioning. On the other hand, an overly lax operationalization of healthy aging may inadvertently categorize older adults with serious health concerns as having aged healthily. Research on healthy aging assessed on a continuum appears to avoid the pitfalls of past research while retaining the capacity of assessing predictors of healthy aging along different levels (McLaughlin et al., 2012). Moreover, this approach to assessing healthy aging has shown promise in other domains, such as research examining the influence of physical activity (Baker et al., 2009). Thus, future research may benefit from adopting a non-dichotomous conceptualization of healthy aging.

Secondly, existing findings have been predominately limited to the examination of sleep duration and sleep quality. Little is known about the influence of other key sleep parameters such as sleep efficiency, wake after sleep onset, napping, or insomnia severity. Thus, an additional potential avenue for future research would be to expand the focus of sleep and healthy aging research to include other relevant sleep parameters. One particularly relevant conceptual factor of interest for future research may be sleep health. Sleep health is a multifaceted construct which highlights the fact that adequate sleep is more than the absence of a sleep disorder or short sleep duration. Preliminary self-report measures of sleep health have begun to be validated (Ravyts et al., 2019) and would allow for an efficient and cost-effective method of gathering more detailed and comprehensive information on the overall sleep of adults in late-life. A third recommendation for future research would be to consider the potential influence of race/ethnicity and social factors on the relationship between sleep and healthy aging. Existing research has examined factors which predict healthy aging among diverse samples, with the present review including studies conducted in four continents. Yet, little research has explored whether race/ethnicity moderates the relationship between key health behaviors and healthy aging. Social and environmental factors, as well as structural barriers which contribute to health-related disparities and unequal access to healthcare also warrant further examination.

Limitations

This systematic review has several limitations. First, the review only examined studies published in peer-reviewed journals making it susceptible to publication bias. In addition, the review is limited to quantitative studies. Studies which qualitatively assessed the association between sleep and healthy aging were not included and may shed light on older adults’ perceptions of sleep as an important health behavior contributing to their well-being. Finally, the limited number of existing studies and the variability in which sleep and healthy aging were measured precluded a meta-analysis from being conducted.

Conclusions

Due to the small number of studies, as well as the heterogeneity in the assessment of both healthy aging and sleep, no definitive conclusions about the positive, negative, or null longitudinal associations between sleep and healthy aging can be asserted. Nevertheless, healthy aging appears to be cross-sectionally associated with several positive sleep indicators (e.g., better sleep quality, longer sleep duration, absence of a sleep disorder). Future research would benefit from further examining the effect of sleep, particularly sleep health, on the likelihood of aging healthily. Additionally, future longitudinal studies which assesses both sleep and healthy aging on a continuum may clarify the temporal relationship between these two factors. Given the increasing prevalence of older adults as a percentage of the overall population, as well as the growing recognition that healthy aging encompasses more than simply extending life expectancy, identifying modifiable factors that predict healthy aging could have pertinent health implications.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Implications.

The observed associations between sleep and healthy aging suggests that sleep might benefit from prioritization as an important health behavior in late-life – especially given how plastic sleep remains well into the last decades of life (Dzierzewski, Griffin, Ravyts, & Rybarczyk, 2018).

The reviewed studies suggest that sleep can be maintained well into late-life. Thus, while the exact impact of sleep for healthy aging outcomes requires additional research, older adults are likely to benefit from the regular assessment and monitoring of their sleep.

Funding:

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging under Grant K23AG049955.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data Availability Statement:

Data for the present study can be obtained from the corresponding author, JD, upon reasonable request.

References

- Alberts SC, Archie EA, Gesquiere LR, Altmann J, Vaupel JW, & Christensen K (2014). The Male-Female Health-Survival Paradox: A Comparative Perspective on Sex Differences in Aging and Mortality. National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK242444/ [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Clark M, & Luszcz M (2002). Successful Aging in the Australian Longitudinal Study of Aging: Applying the MacArthur Model Cross–Nationally. Journal of Social Issues, 58(4), 749–765. 10.1111/1540-4560.00288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S, Moazen-Zadeh E, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA (2017). Racial Discrimination during Adolescence Predicts Mental Health Deterioration in Adulthood: Gender Differences among Blacks. Frontiers in Public Health, 5. 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S, Sonnega A, Pepin R, & Leggett A (2017). Residual Effects of Restless Sleep over Depressive Symptoms on Chronic Medical Conditions: Race by Gender Differences. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 4(1), 59–69. 10.1007/s40615-015-0202-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austad SN, & Fischer KE (2016). Sex Differences in Lifespan. Cell Metabolism, 23(6), 1022–1033. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J, Meisner BA, Logan AJ, Kungl A-M, & Weir P (2009). Physical Activity and Successful Aging in Canadian Older Adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 17(2), 223–235. 10.1123/japa.17.2.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA, Chen X, Chang JJ, Gamaldo AA, Eid SM, & Zonderman AB (2017). Sex and age differences in the associations between sleep behaviors and all-cause mortality in older adults: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Sleep Medicine, 36, 141–151. 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins J, & Rothstein HR (2009). Converting among effect sizes. Introduction to Meta-Analysis, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Cheng Y, Germain A, Moul DE, Franzen PL, Fletcher M, & Monk TH (2010). Night-to-night sleep variability in older adults with and without chronic insomnia. Sleep Medicine, 11(1), 56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, & Miller MA (2010). Sleep Duration and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Sleep, 33(5), 585–592. 10.1093/sleep/33.5.585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calasanti T, & King N (2021). Beyond successful aging 2.0: Inequalities, ageism, and the case for normalizing old ages. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(9), 1817–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernin PA, Lysack C, & Lichtenberg PA (2011). A Comparison of Self-Rated and Objectively Measured Successful Aging Constructs in an Urban Sample of African American Older Adults. Clinical Gerontologist, 34(2), 89–102. 10.1080/07317115.2011.539525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Cohen P, & Chen S (2010). How Big is a Big Odds Ratio? Interpreting the Magnitudes of Odds Ratios in Epidemiological Studies. Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation, 39(4), 860–864. 10.1080/03610911003650383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J-H, Lauderdale D, & Waite L (2016). Social Participation and Older Adults’ Sleep. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 149, 164–173. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford-Achour E, Dauphinot V, Martin MS, Tardy M, Gonthier R, Barthelemy JC, & Roche F (2014). Can subjective sleep quality, evaluated at the age of 73, have an influence on successful aging? The PROOF study. Open Journal of Preventive Medicine, 04(02), 51. 10.4236/ojpm.2014.42008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll HC, Serody L, Patrick S, Maurer J, Bensasi S, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Nofzinger EA, Bell B, Nebes RD, Miller MD, & Reynolds CF (2008). Sleeping well, aging well: A descriptive and cross-sectional study of sleep in “successful agers” 75 and older. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(1), 74–82. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181557b69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugarova E (2017). Ageing, older persons and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations Development Programme; New York. [Google Scholar]

- Dzierzewski JM, Griffin SC, Ravyts S, & Rybarczyk B (2018). Psychological Interventions for Late-Life Insomnia: Current and Emerging Science. Current Sleep Medicine Reports, 4(4), 268–277. 10.1007/s40675-018-0129-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, & Walsh J (2004a). Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: Results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56(5), 497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, & Walsh J (2004b). Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56(5), 497–502. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, Buijs RM, Kreier F, Pickering TG, Rundle AG, Zammit GK, & Malaspina D (2007). Sleep duration as a risk factor for diabetes incidence in a large US sample. Sleep, 30(12), 1667–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Goodkind D, & Kowal P (2016). An Aging World: 2015. 10.13140/RG.2.1.1088.9362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, Hazen N, Herman J, Katz ES, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Neubauer DN, O’Donnell AE, Ohayon M, Peever J, Rawding R, Sachdeva RC, Setters B, Vitiello MV, Ware JC, & Adams Hillard PJ (2015). National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health, 1(1), 40–43. 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch CC, Dew MA, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Buysse DJ, Houck PR, Machen MA, & Kupfer DJ (1994). A Longitudinal Study of Laboratory- and Diary-Based Sleep Measures in Healthy “Old Old” and “Young Old” Volunteers. Sleep, 17(6), 489–496. 10.1093/sleep/17.6.489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu W-C, Tsai AC, Chen Y-C, & Wang J-Y (2017). Predicted factors for older Taiwanese to be healthy octogenarians: Results of an 18-year national cohort study. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 17(12), 2579–2585. 10.1111/ggi.13112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendig H, Browning CJ, Thomas SA, & Wells Y (2014). Health, Lifestyle, and Gender Influences on Aging Well: An Australian Longitudinal Analysis to Guide Health Promotion. Frontiers in Public Health, 2. 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C-W, Yun KE, Jung H-S, Chang Y, Choi E-S, Kwon M-J, Lee E-H, Woo EJ, Kim NH, Shin H, & Ryu S (2013). Sleep duration and quality in relation to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in middle-aged workers and their spouses. Journal of Hepatology, 59(2), 351–357. 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wu W, Jin H, Zhang X, Xue H, He Y, Xiao S, Jeste DV, & Zhang M (2006). Successful aging in Shanghai, China: Definition, distribution and related factors. International Psychogeriatrics, 18(3), 551–563. 10.1017/S1041610205002966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C-I, Lin C-H, Lin W-Y, Liu C-S, Chang C-K, Meng N-H, Lee Y-D, Li T-C, & Lin C-C (2014). Successful aging defined by health-related quality of life and its determinants in community-dwelling elders. BMC Public Health, 14, 1013. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Byles JE, Xu X, Zhang M, Wu X, & Hall JJ (2016). Association between nighttime sleep and successful aging among older Chinese people. Sleep Medicine, 22, 18–24. 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MS, Sforza E, Barthélémy JC, Thomas-Anterion C, & Roche F (2014). Sleep perception in non-insomniac healthy elderly: A 3-year longitudinal study. Rejuvenation Research, 17(1), 11–18. 10.1089/rej.2013.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinson M, & Berridge C (2015). Successful aging and its discontents: A systematic review of the social gerontology literature. The gerontologist, 55(1), 58–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin SJ, Jette AM, & Connell CM (2012). An examination of healthy aging across a conceptual continuum: Prevalence estimates, demographic patterns, and validity. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 67(7), 783–789. 10.1093/gerona/glr234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisinger C, Heier M, Löwel H, Schneider A, & Döring A (2007). Sleep duration and sleep complaints and risk of myocardial infarction in middle-aged men and women from the general population: The MONICA/KORA Augsburg Cohort study. Sleep, 30(9), 1121–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TP, Broekman BFP, Niti M, Gwee X, & Kua EH (2009). Determinants of Successful Aging Using a Multidimensional Definition Among Chinese Elderly in Singapore. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(5), 407–416. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31819a808e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, & Vitiello MV (2004). Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: Developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep, 27(7), 1255–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu JT, Ramsey CM, Tzuang M, Kaufmann CN, Parisi JM, & Spira AP (2018). Napping Characteristics and Restricted Participation in Valued Activities Among Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 73(3), 367–373. 10.1093/gerona/glx166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel NM, McClure RJ, & Bartlett HP (2005). Behavioral determinants of healthy aging. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(3), 298–304. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno R, & Wilson-Genderson M (2012). Adherence to Clusters of Health Behaviors and Successful Aging. Journal of Aging and Health, 24(8), 1279–1297. 10.1177/0898264312457412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjbaran Z, Keefer L, Stepanski E, Farhadi A, & Keshavarzian A (2007). The relevance of sleep abnormalities to chronic inflammatory conditions. Inflammation Research, 56(2), 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravyts SG, Dzierzewski JM, Perez E, Donovan EK, & Dautovich ND (2019). Sleep Health as Measured by RU SATED: A Psychometric Evaluation. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 0(0), 1–9. 10.1080/15402002.2019.1701474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattan SI (2014). Aging is not a disease: implications for intervention. Aging and disease, 5(3), 196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian CA, Hays RD, & Mangione CM (2002). Do older adults expect to age successfully? The association between expectations regarding aging and beliefs regarding healthcare seeking among older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50(11), 1837–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi WH, Zhang HY, Zhang J, Lyu YB, Brasher MS, Yin ZX, Luo JS, Hu DS, Fen L, & Shi XM (2016). The Status and Associated Factors of Successful Aging among Older Adults Residing in Longevity Areas in China. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences: BES, 29(5), 347–355. 10.3967/bes2016.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smagula SF, Stone KL, Fabio A, & Cauley JA (2016). Risk factors for sleep disturbances in older adults: Evidence from prospective studies. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 25(Supplement C), 21–30. 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel R, Herzog A, & Köberle S (1999). Polygraphic sleep criteria as predictors of successful aging: An exploratory longitudinal study. Biological Psychiatry, 45(4), 435–442. 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00042-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafaro L, Cicconetti P, Baratta A, Brukner N, Ettorre E, Marigliano V, & Cacciafesta M (2007). Sleep quality of centenarians: Cognitive and survival implications. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 44 Suppl 1, 385–389. 10.1016/j.archger.2007.01.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg JF, Miedema HM, Tulen JH, Hofman A, Neven AK, & Tiemeier H (2009). Sex differences in subjective and actigraphic sleep measures: A population-based study of elderly persons. Sleep, 32(10), 1367–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai L, Zhang H, & Zhang D (2015). Sleep duration and depression among adults: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Depression and Anxiety, 32(9), 664–670. 10.1002/da.22386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data for the present study can be obtained from the corresponding author, JD, upon reasonable request.