Abstract

Objective

To analyze the characteristics of global β-lactamase-producing Enterobacter cloacae including the distribution of β-lactamase, sequence types (STs) as well as plasmid replicons.

Methods

All the genomes of the E. cloacae were downloaded from GenBank. The distribution of β-lactamase encoding genes were investigated by genome annotation after the genome quality was checked. The STs of these strains were analyzed by multi-locus sequence typing (MLST). The distribution of plasmid replicons was further explored by submitting these genomes to the genome epidemiology center. The isolation information of these strains was extracted by Per program from GenBank.

Results

A total of 272 out of 276 strains were found to carry β-lactamase encoding genes. Among them, 23 varieties of β-lactamase were identified, blaCMH (n = 130, 47.8%) and blaACT (n = 126, 46.3%) were the most predominant ones, 9 genotypes of carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase (CHβLs) were identified with blaVIM (n = 29, 10.7%) and blaKPC (n = 24, 8.9%) being the most dominant ones. In addition, 115 distinct STs for the 272 ß-lactamase-carrying E. cloacae and 48 different STs for 106 CHβLs-producing E. cloacae were detected. ST873 (n = 27, 9.9%) was the most common ST. Furthermore, 25 different plasmid replicons were identified, IncHI2 (n = 65, 23.9%), IncHI2A (n = 64, 23.5%) and IncFII (n = 62, 22.8%) were the most common ones. Notably, the distribution of plasmid replicons IncHI2 and IncHI2A among CHβLs-producing strains were significantly higher than theat among non-CHβLs-producing strains (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Almost all the E. cloacae contained β-lactamase encoding gene. Among the global E. cloacae, blaCMH and blaACT were main blaAmpC genes. BlaTEM and blaCTX-M were the predominant ESBLs. BlaKPC, blaVIM and blaNDM were the major CHβLs. Additionally, diversely distinct STs and different replicons were identified.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12866-022-02667-y.

Keywords: Enterobacter cloacae, β-lactamase, Sequence type, Carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase

Introduction

Enterobacter (E. cloacae) belongs to facultative anaerobic Gram-negative bacilli, grouping into the E. cloacae complex group, the family Enterobacterale [1]. Generally, such bacteria colonize soil and water as well as the animal and human gut, representing one of the most leading species described in clinical infections, particularly in vulnerable patients [2]. It has been reported that E. cloacae is frequently associated with a multidrug resistance (MDR) phenotype, due to the inducible overproducing AmpC β-lactamases and acquisition of numerous genetic mobile elements containing resistance [3]. More worrisome, the production of carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase (CHβLs) rendering ineffective almost all β-lactams families have been continually acquired, resulting in the production of super-resistant bacteria carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae (CREL) [4].

β-lactamase is a predominant resistance determinant for β-lactam antibiotics in E. cloacae. To date, there are two classification schemes for β-lactamases, the more groupings in clinical laboratory generally correlate with broadly based molecular classification, where β-lactamases are divided into class A, B, C and D enzymes based on the amino acid sequence [5]. Currently, the most problematic enzymes are plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases (pAmpCs) with blaACT-like ampC genes being highly prevalent [6], extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) with blaSHV and blaCTX-M being widely distributed [7], and CHβLs, all of which are challenging antibiotic effectiveness.

Globally, blaCHβLs such as blaKPC (class A), blaNDM/VIM/IMP (class B) and blaOXA-48 (class D) are of grave clinical concern and proliferating [8]. It was reported that blaNDM-1 and blaNDM-5 were the main blaCHβLs, ST93, ST171 and ST145 was the predominant sequence types (STs) for CREL in a tertiary Hospital in Northeast China during 2010–2019 [9]. Whereas in Japan, blaIMP-1 was the dominant blaCHβLs conferring carbapenem resistance [10], and blaVIM was the main blaCHβLs in France between 2015–2018 [11]. However, the whole distribution of β-lactamase among global E. cloacae is unclear, and information on the clones of E. cloacae spreading internationally remains unknown. As we know that plasmids play an important role in horizontal gene transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARG), and the identification of replicon types is helpful to analyze plasmid characteristics. Further, the association between plasmid replicons and different resistant determinants is essential to understand the role of plasmids in transmission of ARG [12]. For instance, IncN plasmids have been reported to be the predominant replicon types for blaIMP-4-carrying strains [13], however, the prevalence of plasmid replicons among these bacteria were unknown. Notably, the association between IncIγ plasmid encoding blaCMY-2 ß-lactamase and the international ST19 was observed in multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium [14]. Whether or not this phenomenon could be observed in E. cloacae needs to be confirmed.

With the extensive use and development of antibacterial drugs, β-lactamases have evolved rapidly. Meanwhile, due to the rapid development of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) technology, the number of sequenced bacterial genomes has grown enormously, new β-lactamase variants continue to be described. As a common opportunistic pathogen [15], the information on the distribution of β-lactamase among E. cloacae was limited.

In this study, we first explored the distribution of β-lactamase including pAmpCs, blaESBLs and blaCHβLs among E. cloacae isolates based on a global database. For β-lactamase positive strains, the sequence types (STs) and the distribution of plasmid replicons were further investigated. Furthermore, the prevalent characteristics of β-lactamase-producing E. cloacae were analyzed.

Materials and methods

Acquisition of E. cloacae genomes and strain information

A total of 296 E. cloacae genomes were downloaded in batches from NCBI using Aspera software on 16th, Dec 2021 [16]. The genomic quality of these 296 strains was further filtered by Checkm and Quast software [17, 18]. The high-quality genome was defined as “completeness > 90% and containment < 5%”. Meanwhile, the quantity of contigs is required to be “ ≤ 500, and N50 ≥ 40,000”. Twenty genomes that did not meet the above conditions were filtered out. The investigated strains were collected from different years shown in Figure S1A, the collected dates of 58 strains were “blank” meaning that the information was missing. These strains were submitted by 32 countries, mainly from USA (n = 58), France (n = 30), United Kingdom (n = 27), China (n = 24), Japan (n = 18), Singapore (n = 13) and Nigeria (n = 12), other countries were also involved (Figure S1B). The countries of 26 strains remained unknown. Notably, 158 out of 272 strains were hosted by Homo sapiens (n = 158, 58.1%), mainly from gastrointestinal tract (n = 57, 21.0%).

Investigation of β-lactamase among global E. cloacae

To avoid differences in genome gene prediction by different annotation methods. All the 276 genomes were annotated by Prokka software [19], which is a fast prokaryotic genome annotation software. All the strains containing β-lactamase encoding genes were further analyzed.

Analysis on the sequence type of β-lactamase carrying E. cloacae

The self-made Perl program was used to extract the nucleotide coding sequence of genes from each genome sequence file (GBK format) [20]. The allele sequences and allelic profiles of 7 conserved genes of E. cloacae were downloaded from website https://pubmlst.org/. The sequence of the genome was set as “query”, the seven conserved gene sequence files were set as “subject “(database). Blastn alignment analysis was then implemented between query and subject. The thresholds set were as follows: E-value = 1e-5, identity = 100%, matching length = subject gene length.

Investigation of plasmid replicons among ß-lactamase positive E. cloacae

To analyze the distribution of plasmid replicons among β-lactamase-carrying E. cloacae. The genomes were submitted into the website and PlasmidFinder (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/PlasmidFinder/) was used to analyze the presence of plasmid replicons (Identity: 90%; Coverage: 90%).

Statistical analysis

The differences on the distribution of major resistant determinants and plasmid replicons among blaCHβLs-carrying strains and strains without blaCHβLs was analyzed by Chi-square test. Distribution difference on resistant determinants and plasmid replicons among all the β-lactamase-producing and among the blaCHβLs-carrying strains were checked by McNemar test. The distribution rates were statistically different when p value was less than 0.05.

Results

The distribution of β-lactamase among global E. cloacae

In total, 272 out of 276 strains were found to carry β-lactamase encoding genes. There were 23 varieties of ß-lactamase being found, blaCMH (n = 130, 47.8%) and blaACT (n = 126, 46.3%) were the most predominant ones. Other ß-lactamase encoding genes included blaTEM (n = 90, 33.1%), blaOXA (n = 51,18.8%), blaCTX-M (n = 48, 17.6%), blaVIM (n = 29, 10.7%), blaKPC (n = 24, 8.8%), blaSHV (n = 23, 8.5%), blaNDM (n = 22, 8.1%), blaIMI (n = 17, 6.3%), blaMIR (n = 11, 4.0%), blaLAP-2 (n = 10, 3.7%), blaIMP (n = 7, 2.6%), blaDHA (n = 7, 2.6%), blaGES (n = 4, 1.5%), blaCMY (n = 3,1.1%), blaFOX-5 (n = 3,1.1%), blaVEB-3 (n = 2, 0.7%), blaNMC-A (n = 2, 0.7%), blaCARB (n = 2, 0.7%), blaFLC-1 (n = 1, 0.4%), blaORN-1 (n = 1, 0.4%) and blaSCO-1 (n = 1, 0.4%).

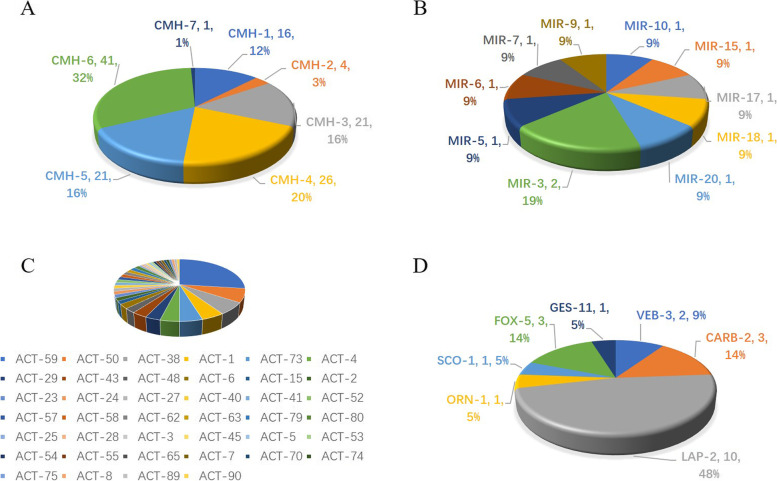

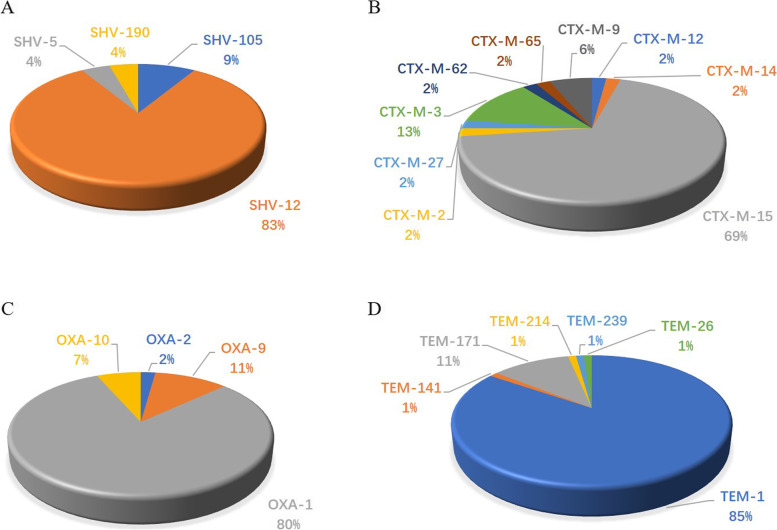

In detail, the variants of pAmpCs including blaCMH, blaACT and blaMIR were shown in Fig. 1, with blaCMH-6 (n = 41, 15.1%) and blaACT-59(n = 34, 12.5%) being the most frequent ones. Multiple variants of blaESBLs including blaCTX, blaTEM, blaOXA and blaSHV were also found (Fig. 2). Among them, blaCTX-M-15 (n = 33, 12.1%) and blaSHV-12 (n = 19, 7.0%) were the most common ones.

Fig. 1.

Variants of the predominant plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases (pAmpCs) among Enterobacter cloacae. 1A, variants of blaCMH; 1B, variants of blaMIR; 1C, variants of blaACT; 1D, variants of other pAmpCs

Fig. 2.

Variants of the predominant extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) among Enterobacter cloacae. 2A, Variants of blaSHV; 2B, Variants of blaCTX-M; 3B, Variants of blaOXA; 4B, Variants of blaTEM

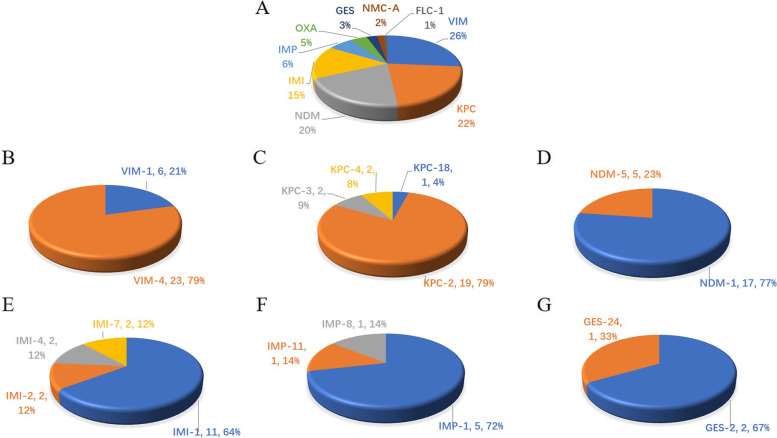

Overall, 9 genotypes of blaCHβLs including blaNDM, blaIMP, blaOXA, blaKPC, blaVIM, blaFLC-1, blaNMC-A, blaGES and blaIMI were found among 106 strains (Fig. 3). Besides the blaCHβLs in the Fig. 3, other ones including blaOXA-48 (n = 3, 2.9%) and blaOXA-181 (n = 2, 1.9%), blaNMC-A (n = 2, 1.9%) and blaFLC-1 (n = 1, 1.0%) were also identified.

Fig. 3.

Variants of the predominant carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase (CHβLs) among Enterobacter cloacae. 3A, carbapenemase detected in this study. 3B, Variants of blaVIM; 3C, Variants of blaKPC; 3D, Variants of blaNDM; 3E, Variants of blaIMI; 3F, Variants of blaIMP; 3G, Variants of blaGES

The distribution of blaACT, blaSHV and blaTEM were obviously higher among blaCHβLs-carrying E. cloacae comparing to the prevalence of these genes among the strains without blaCHβLs (p < 0.05), whereas blaCMH and oxacillin-hydrolyzing-blaOXA were much more prevalent among E. cloacae strains without blaCHβLs than blaCHβLs-carrying ones (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The differences on the distribution of resistant determinants among blaCHβLs positive and blaCHβLs negtive Enterobacter cloacae

| blaCHβLs positive strains (n = 106) | blaCHβLs negative strains (n = 166) | Chi-square value | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaCMH (n = 130) | 41 (38.7%) | 89 (53.6%) | 5.873 | 0.016 |

| blaACT (n = 126) | 60 (56.7%) | 66 (39.8%) | 7.382 | 0.007 |

| blaOXA (n = 51) | 3 (2.8%) | 27 (16.3%) | 10.569a | 0.001 |

| blaCTX-M (n = 48) | 18 (17.0%) | 29 (17.5%) | 0.011 | 0.917 |

| blaSHV (n = 23) | 16 (15.1%) | 5 (3.0%) | 13.255 | 0.000 |

| blaTEM (n = 90) | 61 (57.5%) | 29 (17.5%) | 46.932 | 0.000 |

CHβLs Carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase

a Continuity correction

The sequence types of β-lactamase-carrying E. cloacae

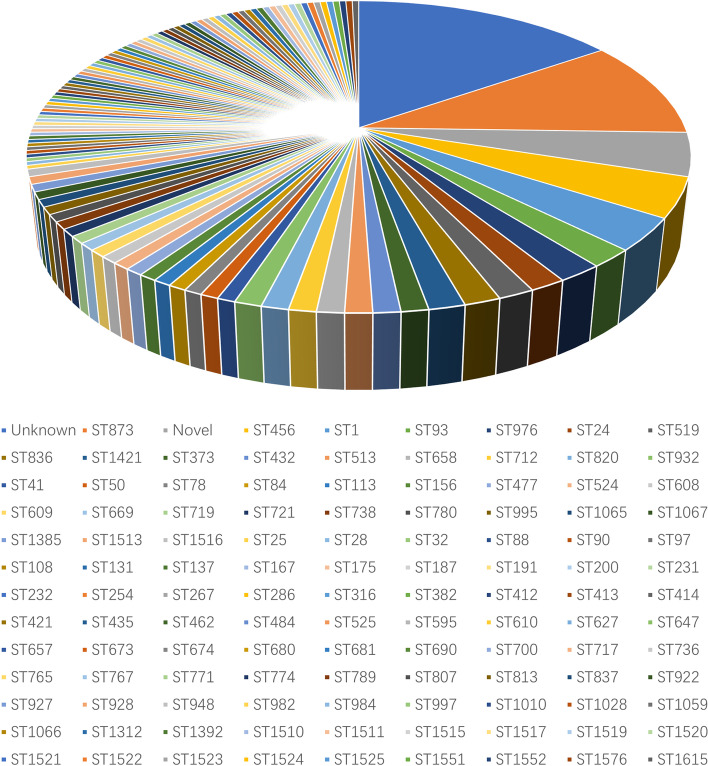

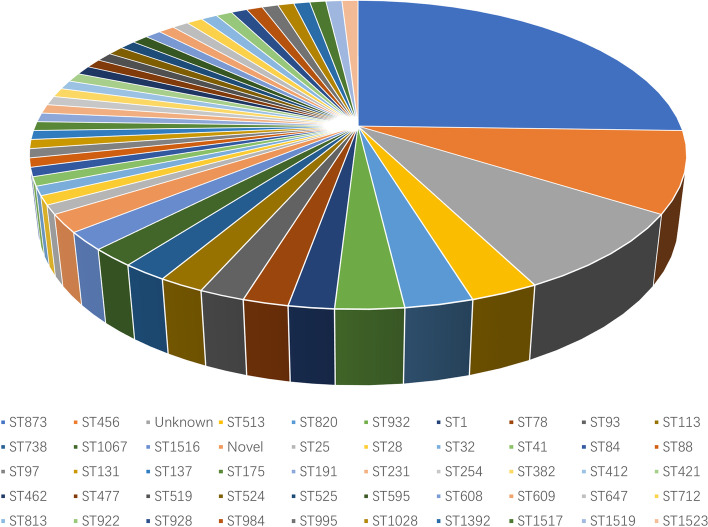

Totally, there were 115 distinct STs for the 272 β-lactamase-carrying E. cloacae (Fig. 4). ST873 (n = 27, 23.5%) was the most frequent one followed by ST456 (n = 11, 9.6%). ST1 (n = 9, 7.8%), ST93 (n = 5, 4.3%) and ST976 (n = 5, 4.3%) were less common. The STs of 41 strains remained unknown and 12 strains belonged to novel STs. Other 110 STs were scattered (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The sequence types of 272 β-lactamase-producing Enterobacter cloacae

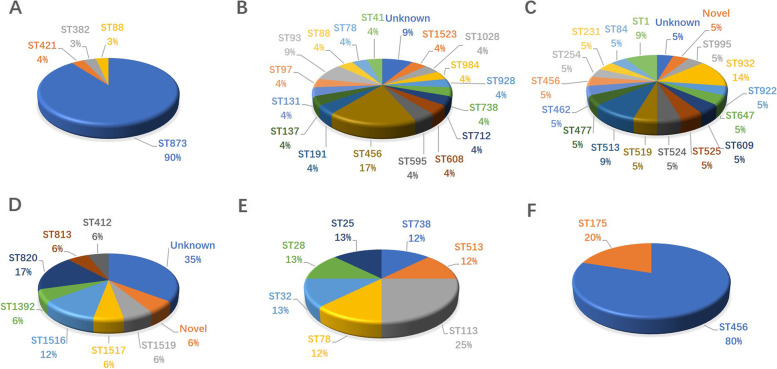

Furthermore, 48 different STs were identified for blaCHβLs-carrying E. cloacae (Fig. 5). And ST873 (n = 27, 25.7%) and ST456 (n = 11,10.5%) was the most common ones. Diverse STs were identified for blaCHβLs-carrying E. cloacae (Fig. 6). Interestingly, all the 23 blaVIM-4-carrying E. cloacae, and 3 out of 6 blaVIM-1- carrying E. cloacae isolates were assigned into ST873 (Fig. 6A). Whereas 19 blaKPC-2 ones were assigned to 13 STs (Fig. 6B), and 17 blaNDM-1 ones were assigned into 14 STs (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, 9 distinct STs for 17 blaIMI- carrying strains (Fig. 6D), 7 different STs for 7 blaIMP-carrying ones (Fig. 6E) and 2 STs for 5 strains carrying carbapenem-hydrolyzing blaOXA (Fig. 6F) were identified. Of note, 27 out of 34 blaACT-59 were found to be carried by ST873 strains.

Fig. 5.

The sequence types of 106 carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase-producing Enterobacter cloacae

Fig. 6.

The sequence types of dominant carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase-producing Enterobacter cloacae. 6A, the sequence types (STs) of blaVIM-carrying strains; 6B, The STs of blaKPC-carrying strains; 6C, STs of blaNDM-carrying strains; 6D, STs of blaIMI-carrying strains; 6E, STs of blaIMP-carrying strains; 6F, STs of blaOXA-carrying strains

The plasmid replicons of CHβLs-carrying E. cloacae

Totally, 25 different plasmid replicons were identified. IncHI2 (n = 65, 23.9%), IncHI2A (n = 64, 23.5%) and IncFII (n = 62, 22.8%) were the most common ones followed by IncCol (n = 48, 17.6%), IncFII (n = 41, 15.1%) and IncR (n = 28, 10.3%). IncFIA (n = 20, 7.4%), IncN (n = 18, 6.6%), IncX3 (n = 12, 4.4%), IncC (n = 8, 2.9%), IncHI1B (n = 8, 2.9%), IncM1 (n = 7, 2.6%), IIncHI1A (n = 6, 2.2%), IncP6 (n = 5, 1.8%), pKPC-CAV1193 (n = 4, 1.5%), IncQ1 (n = 3, 1.1%), IncL (n = 3, 1.1%), IncX5 (n = 2, 0.7%), IncX4 (n = 1, 0.4%), IncM2 (n = 1, 0.4%), IncN2 (n = 1, 0.4%), IncP1 (n = 1, 0.4%), IncA (n = 1, 0.4%), repA (n = 1, 0.4%) and repB (n = 1, 0.4%) were also found. It was worth mentioning that no plasmid replicons were found among 97 strains, 62 (22.8%) out of which only contained one blaCMH, 21 (7.7%) ones carried blaCHβLs.

Notably, the prevalence of replicons IncHI2 and IncHI2A among blaCHβLs -carrying strains were significantly higher than that among the strains without blaCHβLs (p < 0.05), whereas no significant difference on the prevalence of plasmid replicons IncCOI, IncFII, IncFIB and IncR among these two groups were observed (Table 2).

Table 2.

The differences on the distribution of plasmid replicons among blaCHβLs positive and blaCHβLs negtive Enterobacter cloacae

| blaCHβLs positive strains (n = 106) | blaCHβLs negtive strains (n = 166) | Chi-square | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IncCOI (n = 41) | 21 (19.8%) | 20 (12.4%) | 3.046 | 0.081 |

| IncFII (n = 62) | 28 (26.4%) | 34 (37.3%) | 1.294 | 0.255 |

| IncFIB (n = 58) | 29 (27.4%) | 29 (17.5%) | 3.771 | 0.052 |

| IncHI2 (n = 65) | 37 (34.9%) | 28 (16.9%) | 11.574 | 0.001 |

| IncHI2A (n = 64) | 37 (57.5%) | 27 (16.3%) | 12.493 | 0.000 |

| IncR (n = 27) | 9 (8.5%) | 19 (11.4%) | 0.612 | 0.434 |

CHβLs Carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase

The distribution of blaSHV was consistent with plasmid replicon IncR, and prevalence of blaCTX-M was in accordance with the prevalence of IncFII, IncFIB and IncHI2A (p > 0.05). Additionally, the prevalence of oxacillin-hydrolyzing-blaOXA and IncFIB as well as IncCOI was accordant (Table 3). Moreover, the prevalence of blaKPC and blaVIM were consistent with the distribution of IncCOI, IncFII, IncFIB, IncHI2 and IncHI2A, and no differences were observed on the distribution of blaIMI, blaNDM and those of IncCOI, IncFII and IncFIB (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 3.

The differences on the distribution of plasmid replicons and resistant determinants among the β-lactamase producing Enterobacter cloacae

| blaCMH (n = 130) | blaACT (n = 126) | blaOXAa (n = 43) | blaCTM-M (n = 47) | blaSHV (n = 21) | blaTEM (n = 90) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IncCOI (n = 48) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.609 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| IncFII (n = 62) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.037 | 0.137 | 0.000 | 0.012 |

| IncFIB (n = 58) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.146 | 0.272 | 0.000 | 0.041 |

| IncHI2 (n = 65) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.023 | 0.038 | 0.000 | 0.005 |

| IncHI2A (n = 64) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.031 | 0.053 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| IncR (n = 28) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.347 | 0.000 |

a Oxacillin-hydrolyzing-OXA

Table 4.

The differences on the distribution of plasmid replicons and resistant determinants among the blaCHβLs -carrying Enterobacter cloacae

| Plasmid replicons | blaKPC (n = 24) | blaIMI (n = 17) | blaVIM (n = 29) | blaNDM (n = 22) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IncCOI (n = 21) | 0.736 | 0.627 | 0.268 | 1.000 |

| IncFII (n = 28) | 0.652 | 0.080 | 1.000 | 0.451 |

| IncFIB (n = 29) | 0.551 | 0.058 | 1.000 | 0.337 |

| IncHI2 (n = 37) | 0.085 | 0.008 | 0.200 | 0.036 |

| IncHI2A (n = 37) | 0.085 | 0.008 | 0.200 | 0.036 |

CHβLs Carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase

Discussion

β-lactamase is a primary resistance determinant, widely disseminating on mobile genetic elements across the opportunistic pathogens including E. cloacae [21]. Exploring the spread characteristics of β-lactamase among E. cloacae based on the global genome database of GenBank is quite important for illustrating the resistance characteristics of such strains and guiding rational drug use in clinic.

Our analysis showed that the number of E. cloacae has been continuously increasing since the genome of first one was submitted in 2003. More than 32 countries all over the world submitted the genomes, indicating the representativeness of these strains. To note, the host of these β-carrying E. cloacae strains were predominantly Homo sapiens, with the gastrointestinal tract being the major isolation resource, suggesting that Homo sapiens were the dominant host and gastrointestinal tract was predilection seat. Importantly, 106 blaCHβLs-carrying E. cloacae strains isolated during 2010–2020 were scattered among global 27 countries and 5 continents, indicating a rapid emergence and wide distribution of such strain, which alerts us the urgency of implementation of prevention and control measures.

Our analysis showed that blaCMH was the most frequent β-lactamase gene. However, literature search with blaCMH as the key word showed that blaCMH-1 was first detected in E. cloacae as a novel blaAmpC gene at a Medical Center in Southern Taiwan [22]. Since then, blaCMH-2 and blaCMH-3 were sequentially identified in India and Europe [22, 23]. Thereafter, no blaCMH was reported in PubMed database albeit genomic analysis showed the widest distribution of these enzyme. To our surprise, the most prevalent blaCMH-6, blaCMH-4, blaCMH-5 and blaCMH-3 were not identified among E. cloacae at all. Moreover, blaORN-1, identified in the chromosome of Raoultella. ornithinolytica in 2004 [24, 25], has never been reported in E. cloacae. Interestingly, blaCARB-2 as a carbenicillin-hydrolyzing enzyme, has been identified within multiple strains including Klebsiella. pneumonia [26], Achromobacter xylosoxidan [27], Escherichia. coli [28], Acinetobacter pittii [29] and E. cloacae [30] in a variety of countries, however, was quite rare in our study. Which may be related to its clinical importance. blaLAP-2 as a narrow-spectrum β-lactamase was also rare in our study, albeit it has been reported [31] [32]. Furthermore, blaSCO-1 was a novel plasmid-mediated class A β-lactamase with carbenicillinase characteristics in E. coli [33], has not been reported in E. cloacae until now. As we know that blaACT was also a plasmid-encoded ampC gene [34]. Although the prevalence of blaACT was secondary to blaCMH in our study, distribution of exact blaACT-variants was not so high. Note worthily, the most common blaACT-59 in our study has never been reported. Which may be due to the limitation of screening methods. It was reported that blaVEB-3 was encoded by the chromosome and located in an integron, and only 2 blaVEB-2 genes were detected in our study. However, outbreak of infection caused by blaVEB-3-carrying-E. cloacae has been reported in China [35],

Additionally, blaKPC, blaVIM, blaNDM, blaIMI and blaIMP were the major blaCHβLs accounting for carbapenem resistance in global E. cloacae. Among them, blaKPC-2 and blaVIM-4 were the most predominant ones. Which is a light different from previous report showing blaKPC-2 and blaIMP-8 was the main blaCHβLs within E. cloacae in China [36]. Noteworthily, 28 blaVIM-4-carrying E. cloacae ST873 were only found in Homo sapiens in France, indicating that there was a clonal dissemination of such strain among Homo sapiens in France during 2010–2020, which was not reported previously, albeit nosocomial infections caused by E. cloacae ST873 in 2 hospitals in France has been reported [37]. As a novel blaCHβLs, blaFLC-1 belongs to Ambler class A β-lactamases, has been identified an E. cloacae Complex isolated from food products [38]. Interestingly, such enzyme displayed a distinctive substrate profile, hydrolyzing penicillin, narrow- and broad-spectrum cephalosporins, aztreonam, and carbapenems but not extended-spectrum cephalosporin. In addition, blaNMC-A, a class A blaCHβL, has been frequently detected in E. cloacae [39, 40] [41, 42], albeit we just found 2 blaNMC-A in this study. As blaCHβLs, blaGES-24 seems to have a broader host than blaGES-2 although we only found 2 blaGES-2 and 1 blaGES-24 in this study. To date, all reports on blaIMI-1 focus on E. cloacae, indicating that E. cloacae may be the best host for blaIMI.

The higher prevalence of blaTEM and blaSHV among blaCHβLs-carriers in our study was in accordance with a previous report to some degree, which showed that blaCTX-M, blaTEM and blaSHV were mostly detected concurrently with blaCHβLs [43]. Albeit no distribution difference of blaCTX-M was observed. Notably, the significantly higher distribution of blaCMH among non-CHβLs-producers may indicate that blaCMH may be the predominant gene conferring β-lactams among the strains without blaCHβLs.

Furthermore, the multiple STs identified in our study displayed a genetic diversity of β-lactamase producing E. cloacae. It seemed that clonal dissemination for such strain was rare except for blaVIM-4-carrying ST873 ones, suggesting that the spread of CREL was mainly mediated by mobile elements such as plasmids.

Additionally, variously distinct plasmid replicons detected in our study indicate their dissemination potential for resistant determinants. Noteworthily, the obviously higher prevalence of IncHI2 and IncHI2A among blaCHβLs-carrying strains may suggest association between blaCHβLs and IncHI2. It was reported that IncHI2 widely detected in global CRE genomes, was termed as 'super-plasmids' resulting from the large size and prolific carriage of resistance determinants [44]. And the consistent distribution of such plasmid and blaKPC and blaVIM may indicate a good cost fitness between them.

There were several limitations in this study. First, the number of E. cloacae was relatively small which may result from the reason that E. cloacae was only little part of E. cloacae complex. Second, the resistance profiles of these strains were not available for us to compare the difference between the genotypes and phenotypes. Some of the strain information were missing, which was not beneficial for us to fully illustrate the characterization of E. cloacae. Third, some new enzymes are devoid of further phenotypic descriptions because they were directly obtained from whole-genome sequencing studies. Anyway, it is currently difficult to draw an accurate global picture of this bacteria, highlighting the need for more comprehensive genome sequence data and genomic analysis.

In summary, almost all the E. cloacae contained β-lactamase encoding gene. Among the global E. cloacae, blaCMH and blaACT were main blaAmpC genes. BlaTEM and blaCTX-M were the predominant ESBLs. BlaKPC, blaVIM and blaNDM were the major CHβLs. Additionally, diversely distinct STs and different replicons were identified.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Tianshe Li for providing technical help on data sorting and bioinformatic analysis.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Laboratory Medicine, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, the affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School, and the Clinical Research Center, the second hospital of Nanjing, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, 210,003, China.

Abbreviations

- CRE

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae

- ESBLs

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases

- CHβLs

Carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase

- pAmpCs

Plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases

- CREL

Carbapenem resistance Klebsiella pneumoniae

- KPC

Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase

- NDM

New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase

- ESBLs

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases

- MLST

Multi-locus sequence typing

- STs

Sequence types

Authors’ contributions

HJC performed the Bioinformatics analysis and writing; LJ sorted the data and help with the writing; LC, LCC and ZY interpreted the data regarding the resistant determinants and plasmid replicons. XH performed statistical analysis. SH and CXL designed the work and were a major contributor in revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81902124 and 82002205).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from GenBank and the accession number and web link to datasets for the provided name of these strains were shown in table S1.xlsx.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jincao Hu and Jia Li contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Han Shen, Email: shenhan10366@sina.com.

Xiaoli Cao, Email: cao-xiao-li@163.com.

References

- 1.Wu W, Wei L, Feng Y, Xie Y, Zong Z. Precise species identification by whole-genome sequencing of enterobacter bloodstream infection. China Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(1):161–169. doi: 10.3201/eid2701.190154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stokes W, Peirano G, Matsumara Y, Nobrega D, Pitout JDD. Population-based surveillance of Enterobacter cloacae complex causing blood stream infections in a centralized Canadian region. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2022;41(1):119–125. doi: 10.1007/s10096-021-04309-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ito A, Nishikawa T, Ota M, Ito-Horiyama T, Ishibashi N, Sato T, et al. Stability and low induction propensity of cefiderocol against chromosomal AmpC beta-lactamases of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter cloacae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(11):3049–3052. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davin Regli A, Lavigne JP, Pages JM. Enterobacter spp.:update on taxonomy, clinical aspects, and emerging antimicrobial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32(4):e00002–19. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tooke CL, Hinchliffe P, Bragginton EC, Colenso CK, Hirvonen VHA, Takebayashi Y, et al. beta-Lactamases and beta-Lactamase Inhibitors in the 21st Century. J Mol Biol. 2019;431(18):3472–3500. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peymani A, Naserpour-Farivar T, Yeylagh-Beygi M, Bolori S. Emergence of CMY-2- and DHA-1-type AmpC β-lactamases in Enterobacter cloacae isolated from several hospitals of Qazvin and Tehran. Iran Iran J Microbiol. 2016;8(3):168–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garza-Gonzalez E, Bocanegra-Ibarias P, Bobadilla-Del-Valle M, Ponce-de-Leon-Garduno LA, Esteban-Kenel V, Silva-Sanchez J, et al. Drug resistance phenotypes and genotypes in Mexico in representative gram-negative species: Results from the infivar network. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(3):e0248614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han R, Shi Q, Wu S, Yin D, Peng M, Dong D, et al. Dissemination of Carbapenemases (KPC, NDM, OXA-48, IMP, and VIM) among carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae isolated from adult and children patients in China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:314. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Tian S, Nian H, Wang R, Li F, Jiang N, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae complex in a tertiary Hospital in Northeast China, 2010–2019. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):611. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06250-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kananizadeh P, Oshiro S, Watanabe S, Iwata S, Kuwahara-Arai K, Shimojima M, et al. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant and colistin-susceptible Enterobacter cloacae complex co-harboring blaIMP-1 and mcr-9 in Japan. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):282. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05021-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emeraud C, Petit C, Gauthier L, Bonnin RA, Naas T, Dortet L. Emergence of VIM-producing Enterobacter cloacae complex in France between 2015 and 2018. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2022;77(4):944–951. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkab471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rozwandowicz M, Brouwer MSM, Fischer J, Wagenaar JA, Gonzalez-Zorn B, Guerra B, et al. Plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(5):1121–1137. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W, Dong H, Yan T, Liu X, Cheng J, Liu C, et al. Molecular Characterization of bla IMP - 4 -Carrying Enterobacterales in Henan Province of China. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:626160. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.626160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong N, Li Y, Zhao J, Ma H, Wang J, Liang B, et al. The phenotypic and molecular characteristics of antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium in Henan Province, China. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):511. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05203-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Q, Lin Y, Li Z, Lu L, Li P, Wang K, et al. Characterization of a new transposon, Tn6696, on a bla NDM- 1-carrying plasmid from multidrug-resistant enterobacter cloacae ssp. dissolvens in China. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:525479. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.525479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim T, Seo HD, Hennighausen L, Lee D, Kang K. Octopus-toolkit: a workflow to automate mining of public epigenomic and transcriptomic next-generation sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(9):e53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khezri A, Avershina E, Ahmad R. Hybrid assembly provides improved resolution of plasmids, antimicrobial resistance genes, and virulence factors in escherichia coli and klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates. Microorganisms. 2021;9(12):2560. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9122560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornet L, Meunier L, Van Vlierberghe M, Leonard RR, Durieu B, Lara Y, et al. Consensus assessment of the contamination level of publicly available cyanobacterial genomes. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(7):e0200323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchi E, Jones M, Klenerman P, Frater J, Magiorkinis G, Belshaw R. BreakAlign: a Perl program to align chimaeric (split) genomic NGS reads and allow visual confirmation of novel retroviral integrations. BMC Bioinformatics. 2022;23(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s12859-022-04621-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Q, Wang X, Wang J, Ouyang P, Jin C, Wang R, et al. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: Data From a Longitudinal Large-scale CRE Study in China (2012–2016) Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(suppl_2):S196–S205. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ku YH, Lee MF, Chuang YC, Yu WL. Detection of Plasmid-Mediated beta-Lactamase Genes and Emergence of a Novel AmpC (CMH-1) in Enterobacter cloacae at a Medical Center in Southern Taiwan. J Clin Med. 2018;8(1):8. doi: 10.3390/jcm8010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingti B, Laskar MA, Choudhury S, Maurya AP, Paul D, Talukdar AD, et al. Molecular and in silico analysis of a new plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamase (CMH-2) in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;48:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.López Hernández I, García Barrionuevo A, Díaz de Alba P, Clavijo E, Pascual A. Characterization of NDM-1- and CMH-3-producing Enterobacter cloacae complex ST932 in a patient transferred from Ukraine to Spain. Enferm Infecc miCrobiol cli (English ed) 2020;38(7):327–30. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bush K. Past and Present Perspectives on beta-Lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Walckenaer E, Poirel L, Leflon-Guibout V, Nordmann P, Nicolas-Chanoine MH. Genetic and biochemical characterization of the chromosomal class a beta-lactamases of Raoultella (formerly Klebsiella) planticola and Raoultella ornithinolytica. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(1):305–312. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.1.305-312.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu LC, Lu JW, Wang J, Xu T, Xu JH. Analyses on distribution and structure of bla(CARB-2) in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Yi Chuan. 2018;40(7):593–600. doi: 10.16288/j.yczz.18-034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu Z, Xu J, He F. Genomic and phylogenetic analysis of multidrug-resistant Achromobacter xylosoxidans ST273 strain MTYH1 co-carrying blaOXA-114g and blaCARB-2 recovered from a wound infection in China. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2021;25:110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2021.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atlaw NA, Keelara S, Correa M, Foster D, Gebreyes W, Aidara-Kane A, et al. Identification of CTX-M Type ESBL E. coli from sheep and their Abattoir environment using whole-genome sequencing. Pathogens. 2021;10(11):1480. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10111480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamolvit W, Derrington P, Paterson DL, Sidjabat HE. A case of IMP-4-, OXA-421-, OXA-96-, and CARB-2-producing Acinetobacter pittii sequence type 119 in Australia. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(2):727–730. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02726-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez-Martinez JM, Nordmann P, Poirel L. Group IIC intron with an unusual target of integration in Enterobacter cloacae. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(1):150–160. doi: 10.1128/JB.05786-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang Z, Mi Z, Wang C. A novel beta-lactamase gene, LAP-2, produced by an Enterobacter cloacae clinical isolate in China. J Hosp Infect. 2008;70(1):95–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kocsis B, Kocsis E, Fontana R, Cornaglia G, Mazzariol A. Identification of blaLAP-2 and qnrS1 genes in the internationally successful Klebsiella pneumoniae ST147 clone. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62(Pt 2):269–273. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.050542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papagiannitsis CC, Loli A, Tzouvelekis LS, Tzelepi E, Arlet G, Miriagou V. SCO-1, a novel plasmid-mediated class A beta-lactamase with carbenicillinase characteristics from Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(6):2185–2188. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01439-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reisbig MD, Hossain A, Hanson ND. Factors influencing gene expression and resistance for Gram-negative organisms expressing plasmid-encoded ampC genes of Enterobacter origin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(5):1141–1151. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang X, Ni Y, Jiang Y, Yuan F, Han L, Li M, et al. Outbreak of infection caused by Enterobacter cloacae producing the novel VEB-3 beta-lactamase in China. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(2):826–831. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.826-831.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dai W, Sun S, Yang P, Huang S, Zhang X, Zhang L. Characterization of carbapenemases, extended spectrum β-lactamases and molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-non-susceptible Enterobacter cloacae in a Chinese hospital in Chongqing. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;14:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beyrouthy R, Barets M, Marion E, Dananché C, Dauwalder O, Robin F, et al. Novel Enterobacter Lineage as Leading Cause of Nosocomial Outbreak Involving Carbapenemase-Producing Strains. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(8):1505–1515. doi: 10.3201/eid2408.180151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brouwer MSM, Tehrani K, Rapallini M, Geurts Y, Kant A, Harders F, et al. Novel Carbapenemases FLC-1 and IMI-2 Encoded by an Enterobacter cloacae Complex Isolated from Food Products. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63(6):e02338–18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02338-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mariotte-Boyer S, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Labia R. A kinetic study of NMC-A beta-lactamase, an Ambler class A carbapenemase also hydrolyzing cephamycins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;143(1):29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swarén P, Maveyraud L, Raquet X, Cabantous S, Duez C, Pédelacq JD, et al. X-ray analysis of the NMC-A beta-lactamase at 1.64-A resolution, a class A carbapenemase with broad substrate specificity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(41):26714–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyd DA, Mataseje LF, Davidson R, Delport JA, Fuller J, Hoang L, et al. Enterobacter cloacae Complex Isolates Harboring bla(NMC-A) or bla(IMI)-Type Class A Carbapenemase Genes on Novel Chromosomal Integrative Elements and Plasmids. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(5):e02578–16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02578-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antonelli A, D'Andrea MM, Di Pilato V, Viaggi B, Torricelli F, Rossolini GM. Characterization of a Novel Putative Xer-Dependent Integrative Mobile Element Carrying the bla(NMC-A) Carbapenemase Gene, Inserted into the Chromosome of Members of the Enterobacter cloacae Complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(10):6620–6624. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01452-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kopotsa K, Osei Sekyere J, Mbelle NM. Plasmid evolution in carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2019;1457(1):61–91. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Macesic N, Blakeway LV, Stewart JD, Hawkey J, Wyres KL, Judd LM, et al. Silent spread of mobile colistin resistance gene mcr-9.1 on IncHI2 'superplasmids' in clinical carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(12):1856.e7–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from GenBank and the accession number and web link to datasets for the provided name of these strains were shown in table S1.xlsx.