Abstract

Hybridomas secreting monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against the Nebraska calf diarrhea strain of bovine rotavirus (BRV) were characterized. Indirect fluorescent-antibody assay, immunodot assay, and immunoprecipitation were used to select hybridomas that produced anti-BRV MAbs. Seven of the MAbs were shown by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blot assay to be reactive with the BRV outer capsid protein, VP7, which has a molecular mass of 37.5 kDa. None of the seven MAbs were reactive with canine rotavirus, bovine coronavirus, or uninfected Madin-Darby bovine kidney cells. Two clones, 8B4 (immunoglobulin G2a [IgG2a]) and 2B11 (IgG1), were found suitable for use in an antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detecting BRV in bovine fecal samples. Both were subtype A specific (G6 subtype) but did not react with all isolates of BRV group A.

Rotavirus, a member of the Reoviridae family, is an important cause of gastroenteritis in young children, calves, monkeys, chickens, pigs, sheep, and horses (1, 14). It is nonenveloped and has double-shelled capsids surrounding a genome of 11 double-stranded RNA segments. Seven serological groups of rotavirus, A to G, have been identified, but only groups A, B, C, D, and G have been characterized well (15). Each group can be differentiated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic mobilities (2, 23).

Among the seven serogroups, group A rotavirus has been studied in greatest detail, and it is the serogroup most commonly found in cattle worldwide. The virus is composed of a core surrounded by VP6, the major inner capsid protein. The outer capsid layers of infectious bovine rotavirus (BRV) particles contain two proteins, VP4 and VP7. The VP4 (P) types are spike protein encoded by RNA segment 4 (19, 21). They constitute important outer capsid proteins with various functions such as hemagglutinating activity (22) and neutralization activity (10, 25, 37), and when cleaved by trypsin into VP5 and VP8, they enhance the infectivity of the virus. There is evidence that rotavirus VP4 sequences are diverse (32). Using monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against VP4, diversity has been shown in the amino acid sequences of epitopes that are critical for cross-reaction and neutralization of rotaviruses (18, 19, 22, 33). Both VP4 and VP7 are associated with stimulation of serotype-specific antibodies and in vivo protection. Serotypes 1 to 4 of VP7 are glycosylated (6). Proteins other than VP4 and VP7, such as VP6, associated with stimulation of serotype-specific antibodies, may participate in protection against BRV infection; however, neutralizing antibodies in vitro have been shown to be specific against VP4 and VP7. Protection against rotavirus infection appears to rely mainly on stimulation of neutralizing antibodies against the outer capsid proteins, VP4 and VP7 (27).

Many established protocols and commercial kits are available to detect rotavirus infection for human diagnostic medical applications including electron microscopy and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The objective of this study was to develop MAbs against bovine rotavirus that can detect group A rotavirus antigen in bovine fecal samples by ELISA and indirect fluorescent-antibody assay (IFA) for diagnostic and research use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus propagation and purification.

The Nebraska calf diarrhea strain of BRV (serogroup A, serotype G6), obtained from the National Veterinary Service Laboratory at Ames, Iowa, was passaged six times in Madin-Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) cells in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium containing trypsin (5 μg/ml) and pancreatin (5 μg/ml) (16). Virus was harvested when 75% of the infected monolayer showed typical cytopathic effects such as rounding and detachment of cells. A previously described procedure for virus purification was followed (17). After three cycles of freezing and thawing, the cells were scraped, pooled, and centrifuged at 35,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C in a Sorvall TH641 rotor. The supernatant was passed through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter, and then polyethylene glycol 8000 was added at a final concentration of 8% (wt/vol). After incubation overnight at 4°C, the precipitated virus was centrifuged at 10,800 × g for 20 min at 4°C in a Sorvall TH641 rotor. Pelleted virus was resuspended in a minimal volume of TNE buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA). Virus was purified on a discontinuous sucrose gradient (10 to 60% [wt/wt]) and then centrifuged at 90,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C in a Sorvall TH641 rotor. The interphase band was collected, diluted in 1× TNE buffer (pH 7.5), and layered on a 20 to 60% (wt/wt) sucrose gradient for centrifugation at 90,000 × g overnight at 4°C. Fractions were collected in 1-ml volumes and then centrifuged at 90,000 × g for 2 h. The purified virus pellet was resuspended in 1× TNE buffer (pH 7.5) for storage at −20°C, and the protein content was quantitated by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce Chemical Company, Rockford, Ill.).

Production of MAbs.

Four-week-old BALB/c mice were injected subcutaneously with 60 μg of purified BRV viral proteins mixed with an equal volume of adjuvant containing TDM plus MPL plus pokeweed mitogen (Ribi ImmunoChem Research, Inc., Hamilton, Mont.). After three injections were administered at 2-week intervals, the mice were sacrificed and their spleen cells were fused with mouse Ag8 myeloma cells by a standard protocol (7). ELISA, IFA, immunodot assay, Western blot assay, immunoprecipitation, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were used to screen hybridoma supernatants for reactivity to BRV. The BRV-positive hybridomas were selected and cloned by limiting dilution. Isotyping of the MAbs was performed using a commercial kit (Bio-Rad Labs, Richmond, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Indirect ELISA for hybridoma screening.

Immunolon 1 flat-bottom microtiter plates (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, Va.) were coated with 50 ng of purified BRV protein per well and incubated overnight at 4°C. A blocking solution of 2% casein enzymatic hydrolysate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.0) was added to each well (50 μl), and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 25 min. Wells were washed five times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T). Fifty microliters of hybridoma supernatant was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 25 min. The plate was washed five times with PBS-T, followed by the addition of 50 μl of secondary goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) horseradish peroxidase (HRPO)-conjugated antibody (dilution, 1:10,000) to each well. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 25 min and then washed five times for 5 min each time with PBS-T. For color development, 50 μl of 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonic acid) (ABTS) substrate was added to each well, the plate was incubated for 15 to 45 min at 37°C, and the absorbance values were read at 405 nm.

IFA test.

BRV-infected (Nebraska calf diarrhea strain) cell culture slides were fixed in acetone for 10 min at 4°C, air dried for 10 min, and then incubated with 50 to 70 μl of hybridoma supernatant for 30 min at 37°C in a humidified chamber. The slides were rinsed with 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4) for 10 min, incubated with a 1:50 dilution of secondary goat anti-mouse IgG fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled antibody at 37°C for 30 to 60 min. After the slides were washed in PBS for 10 min, they were mounted with buffered glycerol (pH 7.2), coverslipped, and then examined with a fluorescence microscope for the presence of apple-green fluorescence indicating BRV-infected cells.

Immunodot assay.

A biodot apparatus (Bio-Rad Labs) was used to stabilize the nitrocellulose membrane for application of BRV-positive and -negative controls. One microgram of purified BRV was applied per well for each MAb to be tested. Uninfected MDBK cell lysate (1 μg) was used for the negative control. After air drying for 10 min, the membrane was cut into strips that were placed in multireservoir trays and blocked with 10% horse serum for 1 h at 4°C with gentle agitation. Each MAb was tested individually against the BRV-positive and -negative samples by incubating with the nitrocellulose strips for 1 h on a shaker at 4°C. The membrane strips were washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) five times for 5 min per wash. A 1:6,000 dilution of horse anti-mouse IgG HRPO-conjugated antibody was applied to the strips, which were incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Prior to adding of 4-chloro-1-naphthol peroxidase (4CN) substrate for color development, the membranes were washed five times in TBS for 5 min per wash.

Western blot assay.

Proteins from purified BRV were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by electroblotting. The membranes were cut into strips that were placed in a multichannel reservoir, blocked with 10% horse serum in TBS (0.025 M Tris [pH 7.4], 0.8% NaCl, 0.02% KCl) at 4°C for 1 h, and then incubated with 1 ml of hybridoma supernatant at 4°C for 1 h. After the membrane strips were washed with TBS five times for 5 min, secondary horse anti-mouse IgG HRPO-conjugated antibody was applied, and the strips were incubated for 1 h at 4°C and then washed five times for a total of 25 min. Antigen-antibody complexes were detected colorimetrically by adding 4CN substrate. The BRV protein with which each MAb reacted was identified by molecular mass, which was determined by calculating the relative migration of the protein compared to a protein molecular mass marker.

Immunoprecipitation test.

The BRV proteins were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with gentle rocking by addition of 1 ml of clarified infected cell lysate to 50 μl of hybridoma supernatants or a positive, polyclonal control serum from BRV-immunized mice. The immune complexes were incubated on ice for 2 h with 10 μl of formalin-fixed Staphylococcus aureus (Cowan 1) which bound to the MAbs. Cells were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 10 min and washed three times for 5 min, first with tryptic soy agar (TSA) containing 1% Triton X-100 and 1% sodium deoxycholic acid, then with TSA alone, and finally with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM EDTA. After centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min, the pellet was resuspended in 20 μl of sample loading buffer and electrophoresed on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel. The gel was blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and specificity was tested using bovine anti-rotavirus, polyclonal, hyperimmune serum (National Veterinary Service Laboratory) as an antibody probe. The blot was incubated with secondary goat anti-bovine IgG HRPO-conjugated antibody. For chromagen development, 4CN was chosen as the substrate.

IHC.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded intestinal tissues in 4-μm sections were used. The tissue sections were heat fixed to glass slides at 55°C for 30 min and then deparaffinized in three changes of Hemo-De (Fisher Scientific, St. Louis, Mo.) xylene substitute for a total of 15 min, followed by rehydration through graded alcohols (100% > 95% > 80%) to distilled water. Sections were treated with 0.01% trypsin for 10 min at room temperature, followed by a 5-min distilled water wash. To quench endogenous peroxidase, 3% H2O2 was applied to the tissues for 5 min at room temperature. The slides were rinsed in distilled water for 5 min and then soaked in PBS-T for 10 min. A protein blocker (PBA; Lipshaw, Pittsburgh, Pa.) was applied to the sections for 10 min at room temperature. Excess blocker was removed, and anti-BRV hybridoma supernatant (dilution, 1:50) was applied to the tissues for a 2-h incubation at 37°C. After a 10-min wash in PBS-T, the slides were incubated with a secondary anti-mouse IgG biotinylated antibody (Vector Labs, Burlingame, Calif.) for 30 min at room temperature and then washed with PBS-T for 10 min. Avidin-biotin complex (Vector Labs) was applied to the tissues, which were then incubated for 30 min at room temperature, washed in PBS-T, and soaked in distilled water for 5 min. As a substrate, DAB was applied to the tissues for 10 min. Following a 5-min distilled water wash, the sections were counterstained with Gill's hematoxylin 1 (Fisher Scientific) for 30 s and placed under lukewarm running tap water for 5 min. After the tissues were dehydrated through graded alcohols (80% > 95% > 100%) to xylene, they were coverslipped with Permount (Fisher Scientific) and examined by light microscopy for BRV-positive stained cells.

Antigen capture ELISA for BRV antigen detection.

Immunolon 1 flat-bottom microtiter plates (Dynex Technologies) were coated with 12.5 ng of semipurified or concentrated MAb (8B4 or 2B11) per well and incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed five times with PBS-T, and residual moisture was tapped onto a paper towel. A 50-μl aliquot of blocking solution (0.5% glycine in PBS) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 25 min and washed five times with PBS-T. Fifty microliters of a 10% (wt/vol) fecal suspension in PBS was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 25 min. The plate was washed five times with PBS-T, and then 50 μl of rabbit anti-rotavirus HRPO-conjugated antibody (dilution, 1:10,000) was added. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and then washed five times with PBS-T. For development, 50 μl of ABTS substrate was added to each well, the plate was incubated for 15 to 45 min at 37°C, and the absorbance value was read at 405 nm.

Rotazyme.

Detectability and specificity of the MAbs in the antigen capture ELISA were directly compared with the Rotazyme II kit (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Ill.). Bovine fecal samples were tested using the Rotazyme II kit following the manufacturer's instructions for human fecal samples.

Calculation of specificity and sensitivity.

The following formulas were used to calculate the specificity and sensitivity of the antigen capture ELISA compared to the Rotazyme II kit (36): (i) sensitivity = [TP/(TP + FN)] × 100, where TP is a true-positive result as determined by the reference assay and FN is a false-negative result, and (ii) specificity = [TN/(TN + FP)] × 100, where TN is a true-negative result as determined by the reference assay and FP is a false-positive result.

RESULTS

Fusion of spleen cells from immunized BALB/c mice with Ag8 myeloma cells produced 14 anti-BRV hybridoma cell lines, of which seven were selected by their specific reactivity with purified BRV antigen as shown by the screening ELISA and by Western blotting (Table 1) under denaturing conditions. All seven MAbs bound to native antigen, as shown by immunoprecipitation assays, and six were reactive by the immunodot assay. Only MAbs 2B11 and 10B1 failed to detect SDS-denatured antigen by Western blotting. Three MAbs, 5F8, 5H8, and 9E7, did not detect acetone-fixed, BRV-infected cells by IFA. Isotyping of the MAbs, following the kit instructions, showed that all were isotype IgG1, except for 1B12 and 8B4, which were IgG2b and IgG2a, respectively (Table 1). Most of the MAbs had a kappa light chain, and two (10B1 and 1B12) had a lambda light chain.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of anti-BRV hybridoma clones by different assays

| MAb | Isotype | Resulta of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect ELISA | IFA | Immunodot blotting | Western blotting | Immunoprecipitation | IHC assay | ||

| 1B12 | IgG2b | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| 2B11 | IgG1 | + | ++ | + | − | + | − |

| 5F9 | IgG1 | − | − | + | ++ | + | − |

| 5H8 | IgG1 | − | − | + | ++ | + | − |

| 8B4 | IgG2a | + | ++ | + | + | + | − |

| 10B1 | IgG1 | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| 9E7 | IgG1 | − | − | + | + | + | − |

++, strongly positive; +, positive; −, negative.

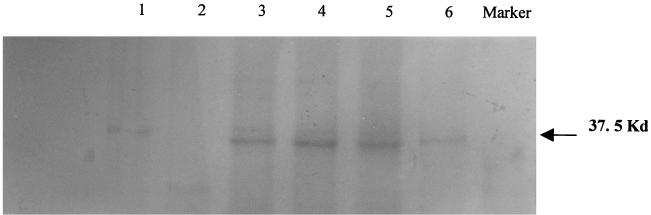

The size of viral protein immunoprecipitated by each of the seven MAbs was calculated by comparing the relative mobility of the bound protein to that of the protein molecular mass marker. A calibration curve of the protein standard was used, and the value of relative mobility of the protein to which the MAb bound was applied to the curve to find the anti-log corresponding to the molecular mass of that protein. All seven MAbs were shown to precipitate with or bind to a 37.5-kDa protein (Fig. 1), which corresponds in molecular mass to rotavirus VP7.

FIG. 1.

Immunoprecipitation of BRV-infected cytoplasmic cell lysate. MDBK cells were infected with BRV, and infected cytoplasmic extracts were immunoprecipitated with MAbs. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with MAbs 2B11 (lane 6), 8B4 (lane 5), 5F9 (lane 4), and 5H8 (lane 3). Noninfected cell lysate was used as a negative control (lane 2), and polyclonal serum against BRV was used as a positive control (lane 1).

MAbs were used in antigen capture ELISA, and the results were compared with those obtained with the Rotazyme II kit (Abbott Laboratories). Clones 2B11 and 8B4 had the ability to detect rotavirus antigen in fecal samples. Of 20 samples tested, 18 that were positive by the Rotazyme II kit were also found positive by MAbs 8B4 and 2B11, with 85 and 39% sensitivity, respectively (Table 2). Sensitivity and specificity of the antigen capture ELISA using each of the two MAbs were evaluated based on the Rotazyme II kit being the reference method (specificity of both MAbs was 100%). Cross-reactivity between BRV antibody and bovine coronavirus, another virus commonly encountered in fecal specimen of neonatal calves, was not observed. Cross-reactivity was not observed with canine rotavirus or with uninfected MDBK cells.

TABLE 2.

Agreement of Rotazyme II kit results with antigen capture ELISA resultsa

| Result of testb

|

Frequency | πi | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rotazyme II kit | ELISA

|

|||

| 8B4 | 2B11 | |||

| + | + | + | 4 | 0.20 |

| − | − | − | 2 | 0.10 |

| + | + | − | 11 | 0.55 |

| + | − | + | 3 | 0.15 |

Agreement was determined with reference to the total number of specimens tested (n = 20). Either MAb 8B4 or MAb 2B11 was used in the ELISA for detecting BRV in calf feces. The total frequency was 20, and πi = frequency/n, where n is the number of samples having a particular outcome (in this case, positive).

+, positive; −, negative. The number of positive results for each test was as follows: for the Rotazyme II kit, 18; for the ELISA with 8B4, 15; and for the ELISA with 2B11, 7.

DISCUSSION

The BRV serotypes are defined according to the reactivity of VP7 to specific MAbs (2, 34). Different segments of BRV encode the VP7 gene (segment 7, 8, or 9, depending on the strain of the virus) (6). VP7 is the main antigen for neutralizing antibodies and determining serotypic differences.

Because binding of an antibody to an antigen is dependent on the recognition of specific amino acid epitopes by the antibody, MAb technology has facilitated the development of sensitive and specific tests for the detection of many microbial and viral antigens in clinical specimens. Several immunological techniques that incorporate the use of MAbs have been described, including ELISA (3, 5, 7, 23, 24, 26, 29, 34), IFA, and fluorescent-antibody assay (8, 28, 30, 31, 33), immunohistochemical staining of fixed tissues (35), and immunoblot assays (9). The advantages of using dot blot immunoassays to detect viral antigens directly from tissues, swabs, washings, and body secretions are as follows: (i) large numbers of specimens can be handled simultaneously; (ii) culture of virus in cells, eggs, or laboratory animals is not required; and (iii) immunoassays are sensitive, specific, and rapid to perform. Coating an ELISA plate with an antigen of interest can result in a change of the conformational epitope to which the MAb may bind. To solve this problem, a sandwich ELISA, in which antibodies are coated in a microtiter plate to anchor the protein of interest and so retain its native conformation, is an alternative.

Accurate and effective diagnosis of BRV infection is important for disease prevention. Current methods for diagnosing infection with BRV are electron microscopic examination of fecal samples, ELISA, and direct fluorescent-antibody inspection of frozen sections of the small intestine. Transmission electron microscopy can detect virus only if large numbers of particles are present (100,000 particles/g of feces), and it is expensive, requiring an operator, special equipment, and skilled personnel. Direct immunofluorescence testing of tissues is rapid, but it is less sensitive than IFA. The latter generally is considered to be more sensitive than direct immunofluorescence because of signal amplification of secondary, labeled antibody. ELISA is sensitive for detecting rotavirus in feces of humans and calves. Commercial ELISA kits, such as the Rotazyme II kit, are useful for detecting rotaviruses of several species because all have a common group-specific antigen. Most available kits are designed primarily for human diagnostic testing and are not approved for veterinary application. Therefore, the use of IFA to detect viral antigen in acetone-fixed tissues is a good alternative to the ELISA, because it is a specific and rapid aid for the study of viral pathogenesis.

In this study, we have produced and characterized MAbs specific for bovine rotavirus. Several screening methods were used to identify BRV-reactive MAbs: immunodot blotting, Western blotting, immunoprecipitation, and ELISA. Differences noted in the reactivity of each MAb by the various tests could be due to the sensitivity of the test or to the conformation of the proteins. For example, both immunoprecipitation and the immunodot assay identify conformational epitopes, whereas Western blotting identifies linear epitopes. Differences in protein conformation can affect reactivity of the antibodies by sequestering or revealing epitopes or weak affinity to MAbs. Differences in the immunodot assay and the indirect screening ELISA could be due in part to differences in test sensitivity. The indirect ELISA is less sensitive than the antigen capture ELISA. Our results show that IFA had a higher sensitivity than indirect ELISA. Immunoprecipitation allows better detection of native conformational epitopes by antibodies than does IFA or dot blot assay. None of the seven MAbs were positive by the IHC test. We believe that the MAbs were nonreactive by IHC because BRV epitopes were distorted by cross-linking induced during formalin fixation of the tissues (3).

This is the first report of MAbs produced against VP7 of Nebraska calf diarrhea strain BRV by using purified viral particles as immunogen. MAbs produced by using synthetic peptide from VP7 as the immunogen for MAb production were unable to detect antirotavirus antibodies as tested by ELISA (12). In another study that used a VP7 peptide-VP6 conjugate as the immunogen, the MAbs produced provided less protection than those obtained by using BRV as the immunogen (13). The MAbs described in this study should aid in serotyping for selection of vaccine candidates and in development of better diagnostic methods for detection of BRV. Because the outer capsid shell, VP7, is associated with stimulation of serotype-specific antibodies, these MAbs may work well for G-typing (G6 serotype) of group A BRV (11, 19). Both MAb 8B4 and MAb 2B11 were G6 subtype specific, and they may be good tools for typing of American and European strains of BRV. These MAbs serve well for diagnosing BRV infection when acetone-fixed slides are submitted for diagnostic investigation. Further study is needed to define and compare the major epitopes and to decide which serotypes (of serotypes G1, G3, and G6) are bound, because each subunit of VP7 induces a different degree of serum neutralization response (4), and then to develop a multivalent vaccine against BRV isolates common in the United States.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jill Speier for help with IFA and Teresa Yeary and Frederick W. Oehme for editorial assistance and advice.

This project was supported by funds from the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station, the Dean's Fund Research Proposal, NC-62 Regional USDA funds for enteric diseases of pig and cattle, and the revenue generated by Kansas State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, Manhattan.

Footnotes

Contribution 00-86-J from the Kansas Agricultural Station, Manhattan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Athanassious R, Marsolias G, Assaf R, Dea S, Descoteaux J, Dulude R, Montpetit C. Detection of bovine coronavirus and type A rotavirus in neonatal calf diarrhea and winter dysentery of cattle in Quebec: evaluation of three diagnostic methods. Can Vet J. 1994;35:163–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birch C J, Heath R L, Gust I D. Use of serotype-specific monoclonal antibodies to study the epidemiology of rotavirus infection. J Med Virol. 1989;24:45–53. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890240107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carson F L. Histotechnology. Chicago, Ill: ASCP Press; 1990. pp. 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crawford S E, Estes M K, Ciarlet M, Barone C, O'Neal C M, Chin J, Conner M E. Heterotypic protection and induction of a broad heterotypic neutralization response by rotavirus-like particles. J Virol. 1999;73:4813–4822. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4813-4822.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czeruy C P, Eichhorn W. Characterization of monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies to bovine enteric coronavirus: establishment of an efficient ELISA for antigen detection in feces. Vet Microbiol. 1989;20:111–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(89)90034-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estes M K, Cohen J. Rotavirus gene structure and function. Microbiol Rev. 1989;3:410–449. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.410-449.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goding J. Purification, fragmentation and isotopic labelling of monoclonal antibodies. In: Goding J W, editor. Monoclonal antibodies. Principles and practice. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 104–141. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heckert R A, Saif L J, Hoblet K H, Agnes A G. Development of protein A-gold immunoelectron microscopy for detection of bovine coronavirus in calves: comparison with ELISA and direct immunofluorescence of nasal epithelial cells. Vet Microbiol. 1990;19:217–231. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(89)90068-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbrink P F, Van Bussel J, Warnaar S O. The antigen spot test (AST): highly sensitive assay for the detection of antibodies. J Immunol Methods. 1982;48:293–298. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(82)90330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoshino M, Ysereno M, Midthun K, Flores J, Kapikian A Z, Chanock R M. Independent segregation of two antigenic specificities (VP3 and VP7) involved in neutralization of rotavirus infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;82:8701–8704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussein H A, Frost E, Talbot B, Shalaby M, Cornaglia E, El-Azhary Y. Comparison of polymerase chain reaction and monoclonal antibodies for G-typing of group A bovine rotavirus directly from fecal material. Vet Microbiol. 1996;51:11–17. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ijaz M K, Alkarmi T O, El-Mekki A W, Galadari S H, Dar F K, Babiuk L A. Priming and induction of anti-rotavirus antibody response by synthetic peptides derived from VP7 and VP4. Vaccine. 1995;13:3312–3318. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)98252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ijaz M K, Attah-Poku S K, Redmond M J, Parker M D, Sabara M I, Frenchick P, Babiuk L A. Heterotypic passive protection induced by synthetic peptides corresponding to VP7 and VP4 of bovine rotavirus. J Virol. 1991;65:3106–3113. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3106-3113.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapikian A Z, Flores J, Hoshino Y, Glass R I, Midthun K, Gorziglia M, Chanock R M. Rotavirus: the major etiologic agent in severe infantile diarrhea may be controllable by a ‘Jennerian’ approach to vaccination. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:815–822. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.5.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapikian A Z, Hoshino Y, Chanock R M, Perez-Schael I. Efficacy of a quadrivalent rhesus rotavirus-based human rotavirus vaccine aimed at preventing severe rotavirus diarrhea in infants and young children. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:65–72. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_1.s65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapil S, Richardson K L, Radi C, Chard-Bergstrom C. Factors affecting isolation and propagation of bovine coronavirus in human rectal tumor-18 cell line. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1996;8:96–99. doi: 10.1177/104063879600800115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King S, Brain D A. Bovine coronavirus structural proteins. J Virol. 1982;42:700–707. doi: 10.1128/jvi.42.2.700-707.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi N, Taniguchi K, Urasawa S. Identification of operationally overlapping and independent cross-reactive neutralization region on human rotavirus VP4. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:2615–2623. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-11-2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu M, Offitt P A, Estes M K. Identification of the simian rotavirus SA11 genome segment 3 product. Virology. 1988;163:26–32. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucchelli A, Kang S Y, Jayasekera M K, Parwani A V, Zeman D H, Saif L J. A survey of G6 and G10 serotypes of group A bovine rotaviruses from diarrheic beef and dairy calves using monoclonal antibodies in ELISA. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1994;6:175–181. doi: 10.1177/104063879400600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackow E R, Barne J W, Chan H, Greenberg H B. The rhesus rotavirus outer capsid protein VP4 functions as a hemagglutinin and is antigenically conserved when expressed by a baculovirus recombinant. J Virol. 1989;63:1661–1668. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1661-1668.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackow E R, Shaw R D, Matsui S M, Dang M N, Greenberg H B. The rhesus rotavirus gene encoding protein VP3: location of amino acids involved in homologous and heterologous rotavirus neutralization and identification of a putative fusion region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:645–649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.3.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNulty M S, Todd D, Allan G M, McFerran J B, Green J A. Epidemiology of rotavirus infection in broiler chicken: recognition of four serogroups. Arch Virol. 1984;81:113–121. doi: 10.1007/BF01309301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noorduyn L A, Meddens M J, Lindeman J, Van-Dijd W C, Herbrink P. Favorable effect of detergent on antigen detection and comparison of enzyme linked detection systems in an ELISA for Chlamydia trachomatis. J Immunoassay. 1989;10:429–448. doi: 10.1080/01971528908053251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Offitt P A, Shaw R D, Greenberg H B. Passive protection against rotavirus induced diarrhea by monoclonal antibodies to surface protein VP3 and VP7. J Virol. 1986;58:700–703. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.2.700-703.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouch C F, Raybould T J G, Acres S D. Monoclonal antibody capture-linked immunosorbent assay for detection bovine enteric cornoavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:3883–3893. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.3.388-393.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rugger F M, Johnson K, Basile G, Kreihenbuhl J P, Svensson L. Anti-rotavirus immunoglobulin A neutralizes virus in vitro after transcystosis through epithelial cells and protects infant mice from diarrhea. J Virol. 1998;72:2708–2714. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2708-2714.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saif L J. Nongroup A rotavirus. In: Saif J, Theil K W, editors. Viral diarrheas of man and animals. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoenthaler S L, Kapil S. Development and application of a bovine coronavirus antigen detection enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;6:130–132. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.1.130-132.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snodgrass D R, Herring A J, Campbell I, Inglis J M, Hargreaves F D. Comparison of atypical rotaviruses from calves, piglets, lambs and man. J Gen Virol. 1984;65:909–914. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-65-5-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tahir R A, Pomeroy K A, Goyal S M. Evaluation of shell vial cell culture technique for the detection of bovine coronavirus. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1995;7:301–304. doi: 10.1177/104063879500700301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taniguchi K, Urasawa T, Urasawa S. Species specificity and interspecies relatedness on VP4 genotypes demonstrated by VP4 sequence analysis of equine, feline, and canine rotavirus strains. Virology. 1994;200:390–400. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taniguchi K, Maloy W L, Nishikawa K, Green K Y, Hoshino Y, Uraswa S, Kapikian A Z, Chanock R M, Gorziglia M. Identification of cross-reactive and serotype 2-specific neutralization epitopes on VP3 of human rotavirus. J Virol. 1988;62:2421–2426. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.7.2421-2426.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsunemitsu H, el-Kanawati Z R, Smith D R, Reed H H, Saif L J. Isolation of coronavirus antigenically indistinguishable from bovine coronavirus from wild ruminants with diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3264–3269. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3264-3269.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unicom L E, Coulson B S, Bishop R F. Experience with an enzyme immunoassay for serotyping human group A rotaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:586–588. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.3.586-588.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanrompay D, Van Nerom A, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F. Evaluation of five immunoassays for detection of Chlamydia psittaci in cloacal and conjunctival specimens from turkeys. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1470–1474. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.6.1470-1474.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Z, Andrews G A, Chard-Bergstrom C, Minocha H C, Kapil S. Application of immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization of bovine coronavirus in paraffin-embedded formalin-fixed intestine. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2964–2965. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2964-2965.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]