Abstract

Objectives:

To characterize the proportion of Medicare Advantage (MA) enrollees who switched insurers or disenrolled to traditional Medicare (TM) in the years immediately after first choosing to join a MA health plan.

Study Design:

Retrospective analysis using 2012-2017 Medicare enrollment data.

Methods:

We studied enrollees who joined MA between 2012 and 2016 and identified all enrollees who changed insurers (switched insurance or disenrolled to TM) at least once between the start of enrollment and the end of the study period. We categorized the type of each change as due to switching insurers or disenrollment to TM and whether the change was due to an insurer exiting the market.

Results:

Among 6,520,169 new MA enrollees, 15.6% changed insurance after 1 year of enrollment in MA and 49.2% had changed by 5 years. More enrollees switched insurers rather than disenrolled, and most enrollees who changed insurers did not do so because of insurer exits.

Conclusions:

New MA enrollees change insurers at a substantial rate when followed across multiple years. These rates may disincentivize insurers from investing in preventative care and chronic disease management, and as shown in several non-MA populations, may lead to discontinuities in care, increased expenditures, and inferior health outcomes.

Precis:

Enrollees who join Medicare Advantage undergo significant turnover in the years following enrollment.

Introduction:

Turnover among enrollees of health plans is a well-studied topic in the commercial,1 Medicaid,1-3 and Affordable Care Act marketplaces.4 Higher rates of insurance switching and disenrollment within these markets have been linked to adverse health outcomes such as delays in seeking medical care,5 lower adherence to medications,2 and increased utilization of higher-cost services such as the emergency department or hospital.2,6 Furthermore, high enrollee turnover may reduce the incentive for health plans to invest in the delivery of certain preventative health services and the management of some chronic medical conditions, as it may take years of continued enrollment before these benefits justify the upfront investment by health plans or other risk-bearing organizations such as Accountable Care Organizations.

While some research has found increased turnover in Medicare Advantage (MA) patients with high healthcare needs,7-10 turnover among the general MA population has received less attention. One study that examined rates of plan switching and disenrollment concluded that only a small percentage of MA enrollees switch plans each year.11 Other research has largely focused on the problems that seniors may face when trying to switch plans, such as difficulty interpreting plan information, low awareness of quality ratings, and overall frustration with the plan selection process.12-14 Overall, MA enrollees are often presumed to be “sticky”, tending to stay with the same insurer once enrolled.15

Differences in health outcomes can become magnified over several years, and insurers may account for enrollment changes over multiple years when planning for future expenditures. The cumulative rate of insurance change after a period of enrollment, rather than yearly rates of change, may better characterize the degree of turnover within MA plans. Thus, we performed a longitudinal analysis of MA enrollment outcomes to measure rates of turnover across multiple years.

Methods:

Using data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF),16 we tracked the enrollment status between 2012-2017 of new MA enrollees, defined as individuals of any age not enrolled in MA the prior year who then choose to enroll. We focused on these enrollees both to reduce confounding by duration of MA enrollment prior to the study and because recent enrollees comprise a significant portion of the MA population,17 the latter of which we verified with data from the MBSF.

We followed each enrollee over time until either a change in insurance, defined as switching insurers or disenrolling to traditional Medicare (TM), or death occurred. Since insurers, otherwise known as parent organizations, can offer multiple plans to enrollees in the same geographic area, we measured switching among insurers, rather than between plans, to better assess the financial impact of turnover on insurers.

We grouped enrollees into cohorts based on year of enrollment and tracked each cohort’s enrollment outcomes annually. At each period, we calculated the percentage of enrollees who had changed insurance at least once since the start of enrollment. Each insurance change was further subcategorized as involuntary if the original insurer exited the enrollee’s county of residence, voluntary if the insurer did not, or due to a move if the enrollee’s county of residence changed; we then calculated trends for each type. Enrollees who left their original insurer due to death were distinguished from those who switched or disenrolled and were included in the denominator but not the numerator when calculating rates of insurance change.

We excluded enrollees in plans not available for individual enrollment, such as employer-sponsored plans, Special Needs Plans, Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) plans, cost plans, Medicare-Medicaid plans, and demonstration plans, as findings for enrollees in these plans are less applicable to the general Medicare population. We used CMS crosswalk files to identify insurer acquisitions and treated these events as if enrollees remained with their original insurer, as the acquiring insurer would be financially responsible for the acquired enrollees.18 In our supplemental analysis, we stratified by dual-eligibility status and whether the beneficiary was new to Medicare (comparing new Medicare beneficiaries to those who switched from TM). We also compared selected demographic characteristics of those who changed insurance to those who did not.

Results:

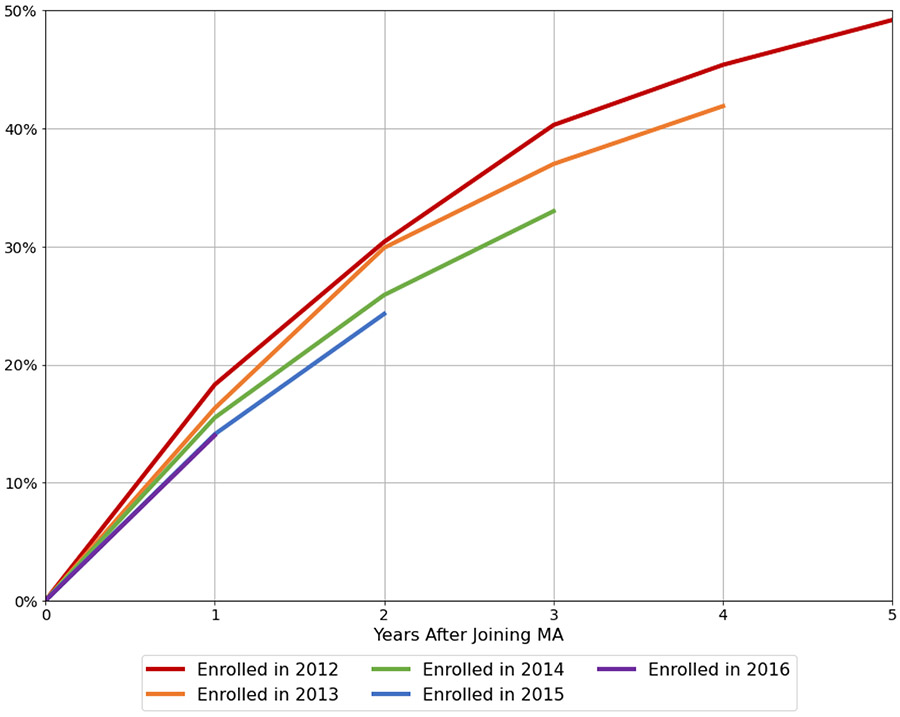

We studied 6,520,169 new MA enrollees who joined between 2012 and 2016, representing approximately 40% of the 16.2 million unique Medicare beneficiaries who were enrolled in individual MA plans between 2012-2017. Overall, 15.6% of new MA enrollees had changed insurance one or more times by the 1-year mark, 27.7% by 2 years, 37.0% by 3 years, 43.7% by 4 years, and 49.2% by 5 years (Figure 1 and eAppendix). Rates decreased somewhat across subsequent cohorts, with 1-year rates falling from 18.3% in the 2012 cohort to 14.0% in the 2016 cohort and 3-year rates falling from 40.3% in the 2012 cohort to 33.1% in the 2014 cohort.

Figure 1: Proportion of Enrollees who Changed Insurance After Newly Enrolling in Medicare Advantagea.

MA, Medicare Advantage.

aInsurance change is defined as either a switch from the enrollee’s original insurer to a different Medicare Advantage insurer or disenrollment to traditional Medicare. See eAppendix Table 1 for exact values.

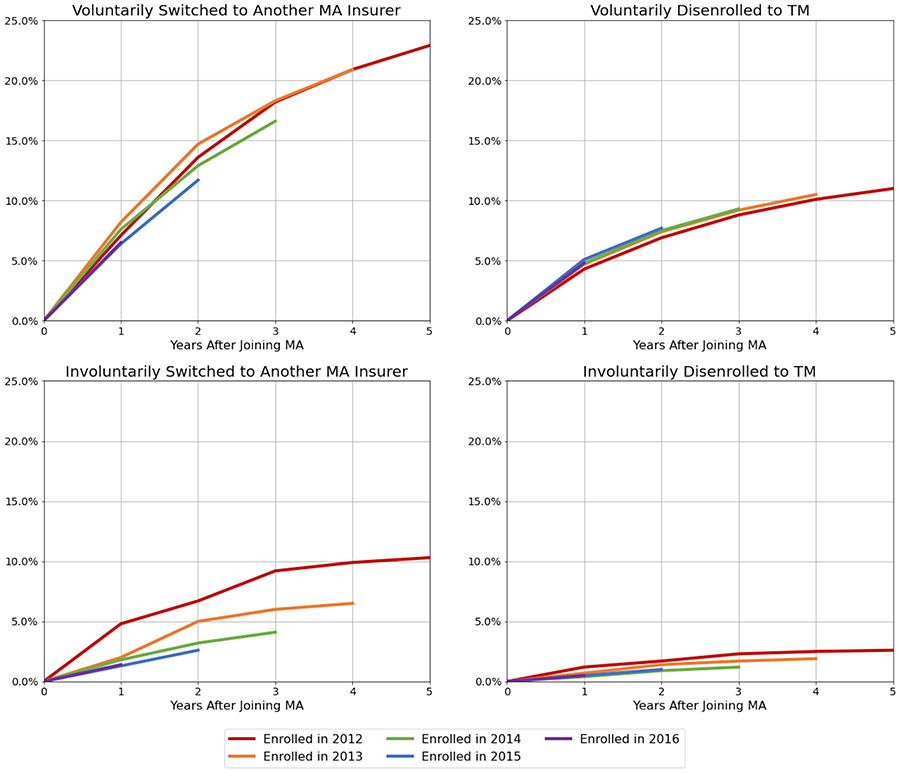

When stratified by type of insurance change, voluntary switching was the most common, averaging 7.1% by 1 year and 22.9% by 5 years of enrollment, though rates declined somewhat across later cohorts (Figure 2 and eAppendix). The rate of voluntary disenrollment to TM was approximately half of voluntary switching and remained stable across successive cohorts. In contrast, the rate of involuntary switching decreased sharply between the 2012 and 2014 cohorts before stabilizing thereafter, while involuntary disenrollments to TM saw a smaller decrease across the same timeframe. When accounting for the size of each subgroup, the decrease in the overall rate of insurance change appears largely driven by decreases in voluntary and involuntary switching prior to the 2015 cohort.

Figure 2: Proportion of Enrollees who Changed Insurance After Newly Enrolling in Medicare Advantage, Stratified by Type of Changea.

MA, Medicare Advantage; TM, traditional Medicare.

aInsurance change is defined as either a switch from the enrollee’s original insurer to a different Medicare Advantage insurer or disenrollment to traditional Medicare. See eAppendix Table 1 for exact values.

Dual-eligible enrollees changed insurance at a higher rate than the general population, though restricting the analysis to non-dual eligible enrollees, new Medicare beneficiaries, or enrollees who switched from TM changed our results by just 1-2% each year (full results in eAppendix). Enrollees who changed insurance, especially those who voluntarily disenrolled, were more likely to have switched from TM when joining MA, to be dual-eligible, and have more chronic conditions on average (eAppendix).

Discussion:

We show that after initial enrollment, MA enrollees continue to change insurance over the next several years, and that insurance changes are driven predominantly by voluntary choices. Relative to other systems, one may naturally expect lower rates of turnover within MA given that enrollment is not affected by changes in employment, as with commercial and ACA plans, or income, as with Medicaid, and since most MA enrollees can only change insurance during Open Enrollment Periods. Remarkably, the rates we report are comparable to rates found in certain non-Medicare populations; for example, 26% of enrollees in a mixed commercial and Medicaid population switched insurers by 2 years, and 13.7% of Medicaid enrollees in expansion states changed or lost coverage within 1 year.1,3

In an earlier report, Jacobson et al. followed MA enrollees across one-year intervals and found that only a small proportion of enrollees change plans each year.11 While our conclusion may appear different due to Jacobson et al. measuring plan-level insurance change, focusing on voluntary switching, and including existing MA enrollees, our one-year switching rates are similar to theirs after accounting for the above (see eAppendix). The main reason for difference appears to be the longer timeframe we used, as changes that are perceived as small on a year-to-year basis can add up significantly over time. Our results complement that of prior research by highlighting that the cumulative effect of turnover may have significant downstream effects on both insurers and enrollees.

A key underlying principle of managed care is that investments in preventive health and improved management of chronic conditions will lead to better long-term patient outcomes and, potentially, lower utilization over time. Insurers, however, are more likely to make such investments if they stand to benefit from the future decreased expenditures. Since Medicare provides coverage for almost all of those over age 65, the Medicare program itself should benefit from efforts to prevent future disease. This does not mean, however, that MA plans, which patients can elect to join and leave on a yearly basis, will benefit in the same way. Our data suggest, in fact, that the turnover in MA enrollment may reduce incentives for MA insurers to invest in better management of chronic medical conditions.

One may assume that if enrollees switch insurers frequently, a significant portion of those who switched would eventually re-enroll with their original insurer, thus obviating the financial disincentive towards future investment. However, insurers who do not invest in these services may be able to “free ride” from those who do, creating an incentive against future investment. This effect has been observed empirically in other health insurance markets where re-enrollment could also occur.19 Furthermore, discontinuities in enrollment could make the implementation of programs to improve prevention or delay disease progression more difficult – for example, an intervention for enrollees with poorly-controlled diabetes may be hindered by spotty data on the frequency of hemoglobin A1c checks – and potentially not as cost-effective.

High turnover rates may also lead to inferior health outcomes among MA enrollees, as has been observed in other insured populations. Discontinuities in medical care has been shown to increase usage of emergency care and hospital length-of-stay in elderly Americans,20 and in non-Medicare populations changes in insurance have also been linked with delays in seeking care, skipping doses of medications, and overall declines in health.1,2 While some enrollees may change insurance to keep access to an existing provider or medication, a switch may still introduce discontinuities of care elsewhere in their care. Though these effects have predominantly studied in non-MA populations, the negative effects of high turnover could be magnified in MA as both medical complexity and healthcare utilization generally increases with age.

Our work also highlights several areas for further research. Our data, like that of prior work7-10, suggest that high-need enrollees disenroll at higher rates. It would be important to both understand their reasons for disenrollment and to assess if any barriers, such as coverage gaps in Medigap for pre-existing conditions, impact subsequent outcomes. Trends in insurance change could also be of interest to policymakers. For example, the decrease in involuntary switching and disenrollment over successive cohorts may reflect the greater financial attractiveness for insurers of MA compared to other insurance markets,21 whereas the decrease in voluntary switching could be suggestive of increased satisfaction among MA enrollees. We caution that the policy implications of these findings are not clear without further investigation.

Limitations:

Our study has several limitations. Because we focused on new enrollees, our results may overestimate the overall rate of insurance change within MA as older enrollees tend to change insurance at lower rates, though our study population did include around 40% of all MA enrollees in individual plans. Rates at four- and five-years after initial enrollment may become lower with more follow-up data given that there was less insurance change in the 2015 and 2016 cohorts. Since we did not track enrollee outcomes after an insurance change, we do not know what fraction of enrollees eventually re-enroll with their original insurer, though these enrollees are still exposed to multiple insurance transitions as described above. Our definition of new enrollees also does allow those who were previously enrolled in MA but disenrolled for multiple years before re-joining to be included. Finally, while we attempted to estimate the fraction of insurance change due to insurer exits, we note that enrollees labeled with an involuntary change may have had other reasons for switching insurance or disenrolling.

Conclusion:

In this study of longitudinal turnover in MA, we show that insurance change among new MA enrollees may be more substantial than previously portrayed, with rates comparable to that of commercial and Medicaid populations. Consequently, turnover in MA may lead to inferior health outcomes through disjointed care and decreased investment in improved care delivery. Future research could help assess the extent to which turnover impacts the care that MA enrollees receive.

Supplementary Material

Takeaway Points:

We performed a longitudinal analysis of enrollment turnover among new Medicare Advantage (MA) enrollees. We found that:

A significant proportion of MA enrollees change insurers within a few years of enrolling in MA.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, the rate of turnover of new MA enrollees was comparable to that of certain commercial and Medicaid markets.

High turnover among MA enrollees may cause disruptions in care, increase utilization of high-cost services, and create incentives against investments in improved care delivery.

Funding:

Supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (P01 AG032952).

References:

- 1.Barnett ML, Song Z, Rose S, Bitton A, Chernew ME, Landon BE. Insurance Transitions and Changes in Physician and Emergency Department Utilization: An Observational Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(10):1146–1155. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4072-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommers BD, Gourevitch R, Maylone B, Blendon RJ, Epstein AM. Insurance Churning Rates For Low-Income Adults Under Health Reform: Lower Than Expected But Still Harmful For Many. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(10):1816–1824. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldman AL, Sommers BD. Among Low-Income Adults Enrolled In Medicaid, Churning Decreased After The Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(1):85–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon SH, Sommers BD, Wilson IB, Galarraga O, Trivedi AN. Risk Factors for Early Disenrollment From Colorado's Affordable Care Act Marketplace. Med Care. 2019;57(1):49–53. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burstin HR, Swartz K, O'Neil AC, Orav EJ, Brennan TA. The effect of change of health insurance on access to care. Inquiry. 1998;35(4):389–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee R, Ziegenfuss JY, Shah ND. Impact of discontinuity in health insurance on resource utilization. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:195. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman M, Keohane L, Trivedi AN, Mor V. High-Cost Patients Had Substantial Rates Of Leaving Medicare Advantage And Joining Traditional Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1675–1681. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Q, Trivedi AN, Galarraga O, Chernew ME, Weiner DE, Mor V. Medicare Advantage Ratings And Voluntary Disenrollment Among Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1):70–77. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyers DJ, Belanger E, Joyce N, McHugh J, Rahman M, Mor V. Analysis of Drivers of Disenrollment and Plan Switching Among Medicare Advantage Beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):524–532. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyers DJ, Rahman M, Rivera-Hernandez M, Trivedi AN, Mor V. Plan switching among Medicare Advantage beneficiaries with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Alzheimers Dement (NY). 2021;7(1):e12150. doi: 10.1002/trc2.12150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson G, Neuman T, Damico A. Medicare Advantage Plan Switching: Exception or Norm? https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-plan-switching-exception-or-norm/. Published September 2016. Accessed June 29, 2021.

- 12.Goldstein E, Fyock J. Reporting of CAHPS quality information to medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(3):477–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biles B, Dallek G, Nicholas LH. Medicare advantage: déjà vu all over again?. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl Web Exclusives:W4–597. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobson G, Swoope C, Perry M, Slosar MC. How are Seniors Choosing and Changing Health Insurance Plans? https://www.kff.org/medicare/report/how-are-seniors-choosing-and-changing-health-insurance-plans/. Published May 2014. Accessed June 29, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuman P, Jacobson GA. Medicare Advantage Checkup. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2163–2172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1804089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Research Data Assistance Center. Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF) Base. https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/mbsf-base. Accessed June 29, 2021.

- 17.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. The Medicare Advantage program: Status report. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar20_medpac_ch13_sec.pd. Published March 2020. Accessed June 29, 2021.

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Plan Crosswalks. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MCRAdvPartDEnrolData/Plan-Crosswalks. Accessed June 29, 2021.

- 19.Herring B Suboptimal provision of preventive healthcare due to expected enrollee turnover among private insurers. Health Econ. 2010;19(4):438–448. doi: 10.1002/hec.1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wasson JH, Sauvigne AE, Mogielnicki RP, et al. Continuity of outpatient medical care in elderly men. A randomized trial. JAMA. 1984;252(17):2413–2417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobson G, Fehr R, Cox C, Neuman T. Financial Performance of Medicare Advantage, Individual, and Group Health Insurance Markets. https://www.kff.org/report-section/financial-performance-of-medicare-advantage-individual-and-group-health-insurance-markets-issue-brief/. Published August 2019. Accessed November 28, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.