Historically, treatment of actinic keratosis (AK) has been summarized by the old adage, “No pain, no gain.” The current treatment paradigm for AKs has been limited by aggressive and often intolerable local skin reactions (LSRs) associated with the topical therapies, instead of improvement outcomes. This has left many dermatologists relying solely on procedures for AK destruction, which are often incomplete in treating the process that leads to development of more AKs.1 Sadly this movement has been promoted by patient preferences, limited access to therapies, and incomplete counseling measures by dermatologists in regard to mitigating associated LSRs and improving tolerability of the topical AK treatments.2

On the other hand, while patients are not often willing to take the risk of appearing red or peeling for even a short treatment course of topical therapy, other modes of AK treatment may still cause them frustration. For example, cryotherapy is painful and can result in dyschromia;2 and despite its efficacy in treating existing AKs and reducing recurrence potential, photodynamic therapy can be just as uncomfortable to patients and is not available in many dermatology practices. Nevertheless, AK remains a very common dermatological problem. In 2015, more than 35.6 million actinic keratosis lesions were treated, increasing from 29.7 million in 2007. According to the United States Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), treated AKs per 1,000 beneficiaries increased from 917 in 2007 to 1,051 in 2015, while mean inflation-adjusted payments per 1,000 patients decreased from $11,749 to $10,942 owing to reimbursement cuts.3 The take-home message here is that treating AK to clearance is not happening in the real world.

The most recent American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines for the treatment of AKs4 suggests that previous topical agents, used alone or in combination with destructive procedures, are endorsed with mixed strength. Tirbanibulin 1% ointment was unique among all topical AK treatments in that it received the AAD’s highest recommendation based on the highest level of evidence, its shorter treatment cycle, and its more tolerable LSRs. As an aside, it was not possible to endorse tirbanibulin 1% ointment in combination with destructive modalities because it was too recently introduced into the market, compared to topical fluorouracil (5FU) or imiquimod.4

A post-hoc pooled analysis of data from two Phase III, randomized, double-blinded, vehicle-controlled studies of Tirbanibulin 1% ointment was performed to assess its tolerability.5 This analysis included data from adults with AK on the face or scalp who completed the Phase III trials and achieved 100-percent clearance in the treatment area (n=174).

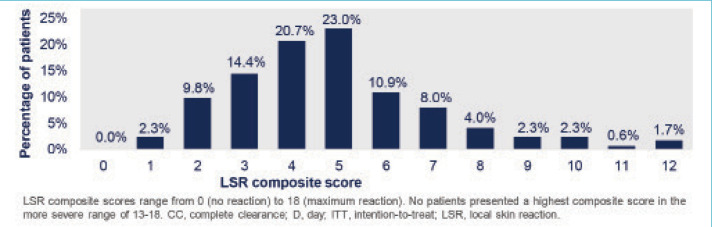

As reported in the study, the mechanisms of tirbanibulin are synthetic inhibitor of tubulin polymerization and Src kinase signaling. Clinically, this translates to promotion of apoptosis as opposed to induction of necrosis, which could potentially result in less clinical incidence of “necrosis” type reactions, such as crusting, swelling, vesiculation/pustulation, and erosion/ulceration.6 The overwhelming majority of the 174 patients in the Phase III studies who achieved complete clearance of the AKs experienced low composite scores of anticipated LSRs, most likely attributed to the proposed mechanisms of action. This post-hoc analysis shows that complete clearance of AK using tirbanibulin 1% ointment was associated with mild-to-moderate LSRs, with 70.2 percent of the patients showing a composite LSR score of 5 or less (Figure 1).5 This suggests that more aggressive reactions were not necessary for induction of clearance. This is supported by the small number of subjects who achieved clearance with higher composite scores.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of local skin reactions (LSR) composite scores from baseline to Day 57 among patients achieving complete clearance (CC)

An important observation from the post-hoc analysis is that none of the subjects withdrew from the studies, with the caveat that after the five-day treatment period, the LSRs were evaluated on Days 8, 15, and 29. In that respect, the LSRs are already in motion by the mechanisms of tirbanibulin and cannot be stopped in the trial, even though in clinical practice they can be mitigated with emollients, topical anesthetics, or other modalities. Moreover, similar to the ingenol mebutate trials of three-day applications, withdrawal from the tirbanibulin trials due to LSRs would not change the outcomes of a patient, compared to other trials with longer treatment times where discontinuation of therapy would eliminate the LSRs.

The results of the post-hoc analysis indicate that clearance does not have to be dependent on aggressive LSRs. This should be used as a discussion point with patients who are both new to topical treatments for AKs as well as those who have experienced negative outcomes. Clearance should also be a function of keeping AKs away, and the durability of response seen in the Phase III trials could improve patient adherence to treatment and encourage repeat courses as necessary. The portion of the study title, “not correlated with the severity of local skin reactions” needs to be understood as not having a grading to match resolution. But the clinician should still be aware of the potential for any patient to develop any grade of LSRs, and this should be part of the discussion with the patient, as well as providing appropriate adjunctive tools to maximize outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Berman B, Cohen DE, Amini S. What is the role of field-directed therapy in the treatment of actinic keratosis? part 1: overview and investigational topical agents. Cutis. 2012;89(5):241–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg G, Berman B, Underhill S. Assessment of local skin reactions with a sequential regimen of cryosurgery followed by ingenol mebutate gel, 0.015%, in patients with actinic keratosis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:1–8. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S70970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung H, Baranowski ML, Swerlick RA et al. Use and cost of actinic keratosis destruction in the Medicare Part B fee-for-service population, 2007; to 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(11):1281–1285. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen D, Asgari MM, Bennett DB et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:e209–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman B, Schlesinger T, Bhatia N Complete clearance of actinic keratosis with tirbanibulin ointment 1% is not correlated with the severity of local skin reactions. Poster presentation. 2022. MauiDerm. for Dermatologists. Maui, Hawaii. 24–28 Jan 2022. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chinnasamy S, Zameer F, Muthuchelian K. Molecular and biological mechanisms of apoptosis and its detection techniques. J Oncol Sci. 2020;6(1):49–64. [Google Scholar]