Abstract

Today, online consumers’ shopping experiences are wholly transformed because of technology to maximize consumer shopping experiences. However, even after increased online shopping after the Covid-19 outbreak, no study has examined the role of demographics in online shopping acceptance. Thus, we filled this gap by employing a cross-sectional design in the UAE and conducting Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). For data gathering purposes, we used structured questionnaires and randomly selected a sample of n = 320 respondents from Al Ain city. Findings revealed strong relationships between Online Shopping, Social Media Usage, and Electronic Word of Mouth (p > 0.000, p > 0.000). Despite the relationships between Social Media Usage, Electronic Word of Mouth, and online shopping acceptance remaining insignificant (p < .384, p < .425), the relationship between Social Media Usage, Online Shopping Acceptance (p > .004) remained significant. Finally, we conducted the mediating analyses and found a substantial mediation of gender between Social Media Usage, Online Shopping Acceptance (p > .000), and Electronic Word of Mouth and Online Shopping Acceptance (p >. 001). Hence, we conclude that people from Al-Ain city primarily rely on online shopping. For this purpose, they consider different factors, including their demographics, i.e., gender, as highly influential on their online shopping acceptance. However, the major limitations of the current study involve selecting gender as the only mediating variable, rejection o two prominent hypotheses, and geographical generalizability of results. Finally, we recommend that future researchers examine the impact of other demographical variables, i.e., age, income, qualification, residence, and others, to examine their impacts on consumer online shopping acceptance.

Keywords: Electronic word of mouth, Social media usage, Online shopping, Gender, Structural equation modelling

Electronic word of mouth; Social media usage; Online shopping; Gender; Structural equation modelling.

1. Introduction

Increased social media usage is a viral phenomenon with the rise of internet technology. Social media facilitates us to gratify specific communication, information, education, and entertainment needs. Especially in terms of fulfilling physical and psychological needs, social media is a pathway to satisfy the relevant needs of potential users (Habes et al., 2020). Social media platforms' role in facilitating shopping is of greater significance (Salloum et al., 2019). Shopping is a basic human need that helps fulfill one's basic needs that help build social and financial bonding among individuals. People shop for different things, based primarily on their needs, that also help them contribute directly or indirectly to the national and international economy (Xu and Lee, 2018). However, during the past few years, the rapidly evolving internet technology has greatly affected these shopping habits in multiple ways. Today, consumers' experiences are entirely transformed because of technology to enhance the consumer shopping experiences at maximum (Alhawamdeh et al., 2020). According to Chang, online users consider online shopping a powerful way of gratifying their purchasing needs. In this context, buying different products from diverse platforms has become trending today (Chang, 2015). As noted by Mehta et al. (2017)., with endless shopping accessibilities and a variety of products and services that are online available, the consumers' experiences are rapidly more consumer-centric. Incorporating the internet into mobile technology further accelerated online shopping. As a result, people now buy and sell products on both international and national levels, entering new markets, fulfilling the consumers' shopping standards, and improving their national and personal financial conditions. Besides, this paradigm shift from traditional to new shopping patterns also motivated the micro and macro level companies to communicate directly with the consumers, showcase their products, and get potential feedback to keep pace with the briskly varying consumer needs (Stenger, 2016). Besides, one of the most prominent advantages of online shopping is products without any barriers. Users can easily click the website links or open the official social media pages of the retailers and buy the products they want (Pham et al., 2020). According to Svatosova (2020), e-marketing is preferred over traditional techniques. Sellers know they can access their customers regardless of geographical, cultural, and language barriers, leading them to adopt a more robust audience-centric approach. In this regard, having a solid brand image and brand loyalty among the consumers are considered two key areas to focus on more. Brand loyalty and brand image help consumers reconsider the same brand for repeatedly making buying decisions even in the future. Moreover, other characteristics, such as access to online shops and ease of use, are essential in persuading consumers to consider online shopping (Ahmed et al., 2019).

Similarly, other factors, such as Electronic Word of Mouth, strongly influence online shopping behavior. It is the phenomenon that affects how others perceive a product and makes relevant shopping decisions. When resorting to Electronic Word of Mouth, potential consumers rely on others' shopping and decision experience, which also helps them make their own decisions (Abir et al., 2020). Also, gender is a vital factor affecting individuals' online shopping decisions. As noted by Ali and their colleagues, gender is a potentially prominent factor that differentiates online decision-making among men and women (Ali et al., 2021). A report represented by The Global Online Consumer Report also affirmed the role of gender in the online shopping decision-making process. As noted, men are more likely to purchase online than through traditional methods. Several studies witness an increased internet usage among men that shows a significant number of users buying and selling the products, indicating men's role as online entrepreneurs and buyers. The same report also showed men as more brand-conscious than women and are more likely to buy highly-priced products (International, 2017). Consequently, we can consider gender as a mediating factor for preferring technology, as suggested by (Ali et al., 2021).

Thus by keeping in view the relationship between shopping, social media usage, Electronic Word of mouth, and online shopping acceptance (Ahmed et al., 2019). examined similar relationships further mediated by gender. However, due to specific research requirements, we conducted this study in the United Arab Emirates to add to the relevant literature. It is also notable that many studies in the United Arab Emirates have addressed the factor behind online shopping acceptance (Appel et al., 2020a; Nuseir, 2019; Yaseen and Jusoh, 2021). However, no study has analyzed the role of gender in affecting social media use and Electronic Word of mouth for online shopping acceptance. Another critical gap in the relevant literature is the increased online shopping activities among Emirati customers after the Covid-19 pandemic. This increased preference also indicates a prominent gap to be filled. Hence, this also shows the existing gap in the current literature that the recent research will fulfill. In this context, the first phase of this research article involves an introduction and over of the problem statement. We have extensively cited studies to support the research topic and develop an explanatory model in the second phase. The third phase involves highlighting a detailed overview of the research design and methods used in this research. The fourth phase involves data analysis based on both descriptive and inferential statistics. Finally, the fifth phase involves discussing results, and conclusions are carefully made accordingly. Notably, the study included the following primary hypotheses:

H1a

There is a significant relationship between shopping habits and social media usage.

H1b

There is a significant relationship between shopping habits and Electronic Word of mouth.

H2

There is a significant relationship between social media usage and Electronic Word of mouth.

H3

There is a significant relationship between social media usage and online shopping acceptance.

H5(a)

Gender significantly mediates the relationship between social media usage and online shopping acceptance.

H5(b)

Gender significantly mediates the relationship between Electronic Word of mouth and online shopping acceptance.

2. Literature review

2.1. Online shopping in the United Arab Emirates

According to statistical data represented by Global Media Insight, today, 98.9% of the Emirati population have active social media accounts. This means that, during the middle of 2022, social media usage in the United Arab Emirates will increase, with 99.0% of the population's daily social media usage, mainly caused by 1.7% of the annual growth of internet users. Notably, this growth and usage statistics remained unchanged from the previous year (Global Media Insight, 2021). Consequently, people in the United Arab Emirates strongly believe that the conventional compulsion to visit the stores to purchase the products exists anymore. Buyers in the United Arab Emirates trust online companies to buy their products (Alghizzawi et al., 2019). From household products to personal care items, e-commerce is rapidly booming in the UAE, indicating a strong dependency on social media for buying, selling, and even personal grooming purposes (Alhawamdeh et al., 2020). A report by Visa Confidential UAE, (2020). also highlights an increased social media usage among the Emirati public for online shopping purposes. With online and physical stores, merchants have a golden opportunity to sustain strong relationships with consumers by providing their products at their doorsteps. This does not mean face-to-face buying is not considered anymore. Still, the attributes associated with online shopping are more likely to attract Emirati consumers that are highly accompanied by accessibility, compatibility, and valuable outcomes, providing the consumers with a great attraction towards online shopping. As noted by (Sayani and Trust, 2019), more than 45% of the public in the United Arab Emirates depends mainly on Business to consumer (B2C) shopping through online platforms. The growing trend of online shopping in the United Arab Emirates can be traced back to 2000 and 2011, when social media users exponentially grew. Visa Confidential UAE further revealed that both demand and supply of online goods and services have remarkably increased during the past two years. The total e-commerce sales in the United Arab Emirates exceeded 16.9 billion USD in 2019, two times higher than the Kingdom of Saadia Araba, where online retailers are still working on their brand image and equity. Stakeholders also forecast increased e-commerce sales to reach approximately $63.8 billion by 2023 (Visa Confidential UAE, 2020). As a result, United Arab Emirates is one of those countries where online purchasing is comparatively higher than the other parts of the world.

2.2. Shopping habits, social media usage, & electronic word of mouth

The emergence of electronic pathways to communication has also led to a revolutionary rise of e-commerce across the globe. For example, as one of the world's biggest exporters, Turkey has availed new opportunities even for micro-level sellers and buyers. Although Business to Business (B2B) export is prominent, Business to Customers (B2C) export is also contributing much to the world's economy in general and the Turkish economy in particular (Kılıç and Ateş, 2018).

Similarly, Taha et al., (2021) also consider the rapidly evolving and advancing social media technology significantly impacting our lives in several ways. Different platforms, also known as "internet-based channels," allow users to access information worldwide. Significantly, the past few years have witnessed the rapid growth of social networking platforms, providing users access to online shops and interactive communication opportunities worldwide. Particularly in terms of shopping and the internet, Voramontri & Klieb (2019) proposed a theoretical diffusion of innovation theory to (Rogers et al., 1962). Social media availability and other relevant characteristics provide consumers with direct access to local and international marketplaces. As a result, the decisions process to purchase anything online rapidly takes place due to several contributive factors, including ease of access, ease of use, and other positive buying experiences. The relationship between shopping habits and social media is further validated as the researcher empirically examined shopping habits and social media usage. The researcher used a literature review approach and made relevant arguments. However, for the researcher, social media marketing is another major factor that helps consumers purchase products online without any hassle or physical effort. Altogether, the availability of social media platforms and social media marketing plays an essential role in providing a safe, easy, and interactive way for buyers to fulfill their buying habits online.

Harun & Omar, (2017) described two significant characteristics of Electronic Word of Mouth, i.e., usefulness and vividness. Usefulness is linked with messages, quality, and communication patterns that enhance one's perception of the functional outcomes of a buying idea. In contrast, vividness involves communication skills, a suitable timeframe, and communicators spreading the Electronic Word of Mouth about an idea, product, or service that further helps the receiver understand the message and act accordingly. In this context, family, peers, experts, and other communication channels spread information. In other words, these factors work as the source of communication in disseminating Electronic Word of mouth. Mainly, negative or positive verbal communication works as feedback and review about a relevant product or service (East et al., 2017). As Hossain et al. (2017) noted, a hostile or positive statement about a service or product word is essential in shaping the customer's decisions. Electronic Word of Mouth works as the distribution of information as a response, choice, and judgment. Organizations can have loyal customers using Electronic Word of mouth strategically to spread positivity about their brand and products. Yet the Electronic Word of mouth still relies on the type and quality of product or service.

2.3. Social media usage and electronic word of mouth (EWOM)

Social media-based word of mouth, widely known as Electronic Word of mouth, is not new. Especially in terms of online marketing, buying, and selling, electronic word of mouth plays a significant role in influencing and shaping consumer behavior. In this context, many companies use Electronic Word of mouth as a social media marketing strategy to increase their sales and brand image among the masses (De Sá Medeiros et al., 2019). As social media-based communication differs from traditional communication patterns, organizations directly access the consumers and market their products. Once the consumers intend to buy and try the product, they share their feedback through their online pages (communities), affecting the other potential buyers' decisions. Electronic word of mouth has evolved from simple face-to-face communication, which is comparatively more accessible and considerable for social media users (Appel et al., 2020). A case study Yaseen & Jusoh (2021) also examined the role of Electronic Word of mouth and consumers' purchase decision-making process, particularly the Middle Eastern social media users. Results indicated that word-of-mouth, especially regarding the product quality, price, delivery services, and seller's behavior towards consumers, remained the most influential factor affecting Electronic Word of mouth. As most of the reviews remained positive, the consumers'' were likelier to buy the products from the online retailers.

Dada (2021) further cited an example of brand equity referring to Electronic Word of mouth. As noted, brand equity is essential due to the brand name with which it is associated. However, a brand name, reputation, and eventually equity depend on product or service quality associated directly or indirectly with the Electronic Word of mouth. Further validated by Zinko and their colleagues Zinko et al. (2021), they examined the effect of Electronic Word of mouth on the positive or negative quality of products on the consumers' buying behavior in Canada. The researchers employed a cross-sectional study design and selected respondents from the hotel customers in Toronto. Results revealed that consumers primarily rely on Electronic Word of mouth to reserve relevant hotel services. Besides, family, friends, and close acquaintances influenced consumers' buying behavior enormously.

Moreover, negative Electronic Word of mouth remains comparatively more influential than positive Electronic Word of mouth. Thus, sharing the Electronic Word of mouth through customer reviews, comments, or even complaints much help the other customers make their buying decision. As the more a product receives positive comments, the more sales occur. But if the comments (reviews) are negative, consumers quit any favorable purchase decision (Anastasiei and Dospinescu, 2019a).

2.4. Social media usage and online shopping acceptance

Today millions of people use the internet daily for different purposes such as entertainment, communication, information, education, and others. However, one of the common causes behind using many online platforms is to gain information. Especially from the e-commerce perspective, people prefer using social media to gain direct access to product information (Taha et al., 2021). Further validated by Waghchoure & Walunj (2021), they also witnessed many studies affirming a solid relationship between social media usage and online purchasing behavior. As noted, despite traditional patterns being still prevalent, and people prefer physically visiting the store as a part of their social life, the advent of social media and increased usage also facilitated many people who sometimes find it difficult to spare time for resuming their shopping activities.

A study by Ying Xu and their colleagues Xu et al. (2021) further examined the proposed relationship between social media usage and online shopping activities in Pakistan. The researchers used the case study method and d randomly selected a sample of n = 300 citizens using social media daily. Results indicated that most respondents use social media for time-killing, escape, and entertainment purposes. Due to these purposes, they also consider online shopping as a source of entertainment and exploring new products. As a result, they consider online shopping an essential part of their everyday lives. As noted by Chung & Muk (2017), one of the distinctive features of internet-based shopping is attracting consumers worldwide. The more organizations adopt e-marketing, the more consumers have exposure to advertising, leading them to visit online shops and purchase the products they like. As a result, today's social media platforms are information-gathering platforms for consumers and help buyers with decision-making. Besides, some characteristics attributed initially to the products available online, i.e., variety, perceived price, trust, website factors, customization, and many others, also accelerate online shopping among potential social media users (Chaudary et al., 2014).

2.5. Electronic word of mouth and online shopping acceptance

Electronic word of mouth (WOM) plays an important role in online shopping decision-making. Anastasiei & Dospinescu, (2019) noted that a global increase in online communication between consumers and retailers leads to the rise of new shopping trends today. To create and sustain a friendly and trustworthy relationship with consumers, online retailers use several strategies that influence consumers' perceptions and help them accept online shopping. These efforts also give retailers economic prosperity and even more strategies to improve product quality and keep brand loyalty and brand image under consumers' consideration. For this purpose, Electronic Word of mouth plays an important in bridging the gap between consumers, buying decision-making, and retailers. However, the question is, how does Electronic Word of mouth affect one's buying behavior (Putra et al., 2020).

Sulthana & Vasantha (2019) answered this question and cited an example of online shopping in India as one of the most trending shopping patterns. Indian consumers widely consider the online reviews written by other individuals who have some shopping experience with the relevant retailers. As a result, Indians consider the electronic word of mouth as comparatively more critical in making buying decisions than traditional buying patterns. On the other hand, Zinko et al. (2021) further discussed the impacts of Electronic Word of mouth on product or service improvement processes. As argued, consumers who have negative experiences with a product briskly share their opinions on online platforms. It leads to uncertainty among consumers still under the decision-making process as to whether or not to buy the product. Besides, retailers with negative comments consider this feedback an essential part of their product/service improvement process. Again, a case study conducted by Nuseir (2019) also examined the role and impact of Electronic Word of mouth on the purchase intention of social media users. The results gathered from n = 387 Emirati social media users revealed that Electronic Word of mouth remained highly important for the study respondents. All the participants indicated their greater dependency on Electronic Word of mouth to make a relevant purchase decision.

Consequently, the reviews of previous customers can reduce or increase the uncertainty and motivate the retailers to improve their services to improve their sales and brand image. Thus, although Electronic Word of mouth profoundly affects consumers' online shopping acceptance and decision-making process, there is still a greater need to examine these impacts. Especially examining their effects on the varying geographical boundaries and cultures can bring even more in-depth findings (Albarq and Doghan, 2020).

2.5.1. Impacts of gender on social media usage and online shopping acceptance

According to Ali and their colleagues Ali et al., (2021), gender is one of the leading factors that directly or indirectly affect social media usage and even online decision-making. Generally, terms can be taken for social media adoption and usage purposes. While in the current research focuses on gender while selecting an online medium for shopping and taking Electronic Word of the Mouth under consideration. As noted by Lim et al. (2019), internet users may differ in different aspects, especially for buying purposes, yet gender remains the most significant factor. For example, Malaysian men are more likely to shop online as they find it convenient, easily accessible, and requires less physical effort. However, females mostly use online platforms for communication and entertainment. Yet, we cannot separate entertainment from shopping, as Malaysian women also consider online shopping for time-killing purposes.

Similarly, a study by Rafiq & Javeid (2018) also examined the potential gender differences in shopping through online platforms in Pakistan. The researcher selected a cross-sectional design and a sample of n = 781 undergraduate-level university students from Lahore. Results showed that females preferred online shopping more than men for female respondents. Online shopping helps fulfill their needs and provides them with a sense of entertainment and escape. Other factors, such as perceived trust and trust in online retailers, further strengthen the intention to accept and adopt online shopping. However, Pradhana & Sastiono, (2019) argued that gender domination is not an apparent phenomenon regarding online shopping. Both males and females can show increased interest in online shopping, depending on their requirements and preferred shopping patterns.

2.5.2. Impacts of gender on electronic word of mouth and online shopping acceptance

Mansour & Farmanesh (2020) also describe gender as a mediating factor in considering word of mouth for online shopping acceptance. A significant difference can be seen based on gender when considering Electronic Word of mouth. Gender is effective whether it is a moderator or mediator as sometimes men and sometimes women increasingly consider Electronic Word of mouth necessary for online shopping decisions. A study by Sánchez Torres et al., (2018) also validated the relevant phenomenon. The researcher empirically examined the mediating role of gender regarding Electronic Word of mouth and online shopping acceptance. The researcher adopted a case study approach and selected n = 21 Spanish social media users that often buy products from different online platforms. Results indicated that both men and women consider online shopping to facilitate traditional shopping patterns and an easy way to check reviews and comments about a brand and its products/services. However, for many male buyers, the credibility of information is of greater importance when making an online buying decision, indicating an attitude toward Electronic Word of mouth as an additional factor in the decision-making process.

According to Babić Rosario et al. (2020), by keeping in view the importance of Electronic Word of mouth, even retailers provide the customers with an online space to share and receive product reviews from each other. Although gender is a prominent factor, we can assume gender is more effective when Electronic Word of mouth is about the products attributed to any specific gender. Thus, gender cannot be overlooked while analyzing its impacts on Electronic Word of mouth. From everyday needs to festival shopping, gender plays a vital role in considering online shopping important shopping patterns in the modern world. Figure 1 below illustrates the explanatory model of the current study. We have adopted two to develop the current research model (Abir, 2020; Ali et al., 2021a; Bilal et al., 2021).

Figure 1.

Explanatory framework of current study.

2.6. Theoretical framework

E-Marketing theory provides theoretical support to current research. According to Dwivedi and their colleagues Dwivedi et al. (2020), earlier, the applicability of marketing patterns was limited due to self-claimed business professionals. These business professionals had their own defined set of rules. However, several theories have been raised after the rise of internet technology, leading to a broader picture of online marketing and its fundamental concepts. As soon as old marketing rules turned out to be typically narrowed, other concepts of eMarketing, such as product, promotion, people, packaging and others, became the focus of the marketers and manufacturers. As a result, social media marketing took place, and marketers widely adopted an audience-centered approach and considered Electronic Word of Mouth, Brand Image, Brand Loyalty, and Customer Satisfaction (Vynogradova et al., 2020). As noted by Teixeira et al. (2018), the rapid emergence of internet technology has greatly facilitated marketers to access their customers. Marketing today has become more than just a traditional piece of image or video clip; rather, it is more like appealing to the consumers through emotions, personally accessing them through emails, popup advertisements, and even product surveys. As a result, a large audience beyond borders also leads to increased exposure and sales. In this regard, elements like Electronic Word of Mouth are essential to accelerate product marketing, influencing sales and brand images among consumers (Hanekom, 2006).

3. Research methods

3.1. Study design and data gathering tool

By keeping in view, the nature and aim of this study, we employed a cross-sectional design to gain maximum data in a limited time. According to Setia (2016), cross-sectional studies help the researchers to gather data directly from the respondents regarding their relevant experiences. These studies are strongly generalizable as their techniques are statistically analyzed and validated. Further, we used structured, close-ended questionnaires designed at a five-point Likert scale for gathering aspirations (Questionnaire is available in the appendix). Moreover, as we developed the questionnaire on some pre-existing studies, the sources of questionnaire items are given in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Sources of research items.

| S/R | Variables | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Social Media Usage & Online shopping | (Mehta et al., 2017) |

| 2. | Social Media Usage & WOM. | (Davis, 2002) |

| 3. | Social Media Usage & Gender | (Ali et al., 2021) |

| 4. | Social media and Online Shopping Acceptance | (Shen and Eder, 2009) |

| 5. | WOM and Online Shopping Acceptance | (Kim and Song, 2010) |

We sent the questionnaires through emails and personal visits to the university, which took approximately six weeks for the data collection process. However, due to Covid-19 restrictions, most questionnaires were filled and returned online. Notably, we approached the participants through the university website and some faculty members that forwarded the questionnaires.

Besides, our questionnaire was based on six sections. First, we asked three demographical questions. Then, the rest of the sections involved a total of n = 15 questions (n = three questions for each variable) and focused on evaluating the responses. Moreover, we conducted data analysis using SPSS version 26 and IBM AMOS 26 for descriptive and inferential statistics, respectively, as suggested by (Civelek, 2018).

3.2. Population and sampling

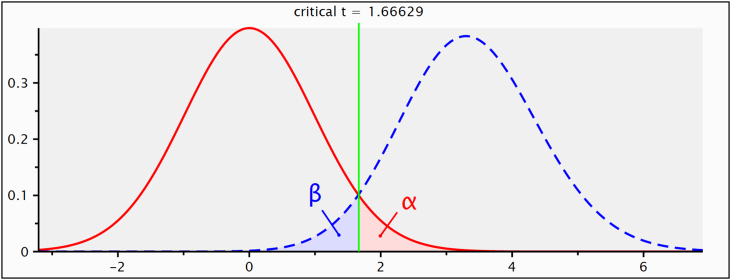

The study population involves individuals from both gender and all age groups using social media for online shopping purposes. However, according to the study criteria and demands, we randomly selected a sample of n = 320 participants from Al-Ain, U.A.E. For this purpose, we emailed the questionnaire link to our respondents by ensuring their consent, availability, and residence in Al Ain city. Besides, we also accessed the respondents in physical settings, especially in malls and one higher education institution. However, it is worth noting that In'nami & Koizumi (2013) suggest an ideal sample when conducting Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) should be a minimum of n = 200 respondents. In this regard, our sample size of n = 320 respondents was ideal. Another important factor adding to the accuracy of the selected sample size is G∗ Power Analysis. According to Sarstedt et al. (2020), G∗ Power is a flexible statistical tool that helps to examine the suitable sample size in research. It is also considered as important as stand-alone power analysis software that can be used for other statistical tests. Thus, G∗ Power Analysis in current research revealed an ideal minimum n = 74 respondents with an effect size of 0.15 and a degree of freedom of 72. Figure 2 illustrates the sample distribution according to the G∗ Power analysis. Notably, the researchers employed a simple random sampling method in the current research due to zero cancer of researchers' own bias (Sarstedt et al., 2020).

Figure 2.

Central and non-central sample distribution.

3.3. Response rate

We used self-administered questionnaires in a real-time face-to-face situation and web-based surveys to gather the maximum responses (Habes et al., 2021). However, after carefully distributing n = 320 questionnaires among the respondents, we received a response rate of 95.0% (n = 304) as n = 16 or 5.0% of questionnaires were incomplete or wrongly filled. The data was gathered from October 1st, 2021, to October 17th, 2021.

3.4. Ethical approval

This research is approved by the Al-Ain University, Scientific Research Committee, AL-Ain City, United Arab Emirates.

4. Data analysis & findings

4.1. Descriptive analysis

Further, we also calculated the frequencies and percentages of the demographical variables of the study participants. As shown in Table 5, a majority of respondents were males (51.0%) and 49.0% were females (M= .490, SD= .501). According to the age group, n = 138 or 45.4% of participants were 30–39 years old, n = 76 or 25.0% were 18 years old or below, n = 58 or 19.1% were 40–50 years old, while n = 32 or 10.5% of respondents were 51 years or above (M= 1.90, SD= 1.26). Finally, the qualification level of respondents revealed that a majority of them (34.5%) had Post Graduation, n = 82 or 27.0% had a Graduate level degree, n = 39 or 12.8% had Undergraduate level qualification, n = 29 or 29.5% of respondents had Doctorate, n = 28 or 9.2% were having some professional Diploma or Certification, while n = 21 or 6.9% of participants marked “others” as their qualification level (M= 2.43, SD= .129). Besides, we also conducted a One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to examine how the respondents' shopping habits vary based on their demographics. With the significance value at p > .007 and .000, we found that gender and qualification remained controlled. However, the significance level at p < .966, the respondents' shopping habits varied based on their age groups, thus, also indicating that age is not a controlled variable (See Table 2 for details).

Table 5.

Heterotrait-monotrait ration scale.

| SHS | SME | WOM | OSA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHS | ||||

| SME | .839 | |||

| WOM | .835 | .839 | ||

| OSA | .751 | .755 | .751 |

Note: SHS is Social Media Habits, SME is Social Media Usage, WOM is Word of Mouth, and OSA is online shopping acceptance.

Table 2.

Respondents’ demographics & one-way ANOVA.

| Variables | Groups | N | % | M | SD | f | Sign |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 155 | 51.0% | .490 | .501 | 2.72 | .007 |

| Female | 149 | 49.0% | |||||

| Age | 18 years or below | 76 | 25.0% | 1.90 | 1.26 | .298 | .966 |

| 30–39 years | 138 | 45.4% | |||||

| 40–50 years | 58 | 19.1% | |||||

| 51 years or above | 32 | 10.5% | |||||

| Qualification | Diploma/Certification | 28 | 9.2% | 2.43 | .129 | 4.71 | .000 |

| Undergraduate | 39 | 12.8% | |||||

| Graduate | 82 | 27.0% | |||||

| Post Graduate | 105 | 34.5% | |||||

| Doctorate | 29 | 9.5% | |||||

| Other | 21 | 6.9% |

4.2. Analysis of measurement model

To examine the measurement model, we first conducted convergent validity and then divergent validity analyses suggested by Mello & Collins (2001). Through analyzing the convergent and divergent validity, we mainly assessed the internal consistency of the constructs. Thus, findings revealed that:

4.2.1. Convergent validity

As summarized in Table 2 below, we first examined the measurement model's Factor Loading and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). We found that a majority of the Factor Loading (ranging between 0.455 to 0.997) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values (ranging between 0.967 to 0.990) surpassed the threshold value of 0.5 as suggested by Salloum et al. (2020). Then we further examined the Cronbach Alpha values and Composite Reliability of constructs. We found that all the Cronbach Alpha Values (CA) range from 0.707 to 0.765. All the Composite Reliability Values range from .727 to 0.80, successfully surpassing the threshold value of 0.7, as suggested by Mohajan, (2017). Thus, we found that all the constructs are internally consistent (See Table 3 for details).

Table 3.

Factor loading, lambda, expulsion, cronbach alpha, average variance extracted, and composite reliability.

| Study Variables | Items | FL | AVE | CA | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shopping Habits | SHS1 | .984 | .973 | .765 | .808 |

| SHS2 | .997 | ||||

| SHS3 | .938 | ||||

| SHS4 | .742 | ||||

| Social Media Usage | SME1 | .987 | .985 | .744 | .752 |

| SME2 | .984 | ||||

| SME3 | .984 | ||||

| SME4 | .575 | ||||

| Word of Mouth | WOM1 | .997 | .990 | .707 | .733 |

| WOM2 | .455 | ||||

| WOM3 | .601 | ||||

| WOM4 | .984 | ||||

| Online Shopping Acceptance | OSA1 | .993 | .967 | .720 | .727 |

| OSA2 | .941 | ||||

| OSA3 | .761 | ||||

| OSA4 | .703 |

4.2.2. Discriminant validity

Moreover, we also conducted a Discriminant Validity analysis; as noted by Ab Hamid et al. (2017), assessing the discriminant validity is one of the essential prerequisites of Structural Equation Modelling. We first analyzed the Fornell-Larcker criterion and calculated the square of all the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values. We found that all the Squared AVE values are more significant than the correlation values in Table 4 below. Later we analyzed the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio by calculating the average of all the correlation values and applying the relevant formula to MS Excel, as suggested by Henseler et al. (2015). The HTMT value is 0.198, smaller than the threshold value of 0.85, indicating that the discriminant validity is successfully established (See Table 5). Thus, discriminant validity in current research indicated that the factors are uncorrelated and distinct, as also suggested by Civelek (2018).

Table 4.

Fornell-larcker criterion.

| SHS | SME | WOM | OSA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHS | .946 | |||

| SME | .945 | .970 | ||

| WOM | .912 | .967 | .980 | |

| OSA | .901 | .953 | .956 | .935 |

Note: SHS is Social Media Habits, SME is Social Media Usage, WOM is Word of Mouth, and OSA is online shopping acceptance.

4.2.3. Absolute model fit

After examining our measurements' convergent and discriminant validity, we further examined the Goodness of Fit suggested by Dijkstra & Henseler, (2015). According to Wong (2013), many software programs provide Goodness of Fit measurement, yet I.B.M. Amos is one of the most preferred ones due to the authenticity of the results. Therefore, in the current study, the model fit analysis revealed the chi-square value of χ2 = −44731.9 (df= 30) with the probability level at 0.000, which is smaller than the threshold value of 0.05. Besides, the Root Mean Square of Error Approximation (RMSEA) value was at GFI ≥.003. In contrast, the value regarding Goodness of Fit remained at 0.530, indicating the GFI value is greater than 0.09, as suggested by Hooper et al. (2008). Hence, we found that the measurement model sits well concerning the set of study observations. Figure 3 graphically illustrates the model indicating Goodness of Fit:

Figure 3.

Goodness of fit.

4.3. Analysis of structural model

To analyze the structural model, we first examined how the independent variable causes variance in the dependent variables, mainly known as "Coefficients of Determination R2”. As noted by Figueiredo Filho et al., (2011), R2 analysis helps determine the predictive power of independent variables, which is considered an essential part of Structural Equation Modeling. Thus, in this research, we found .593 or 59.3% of the variance in Social Media Usage, .528 0r 52.8% of the variance in the Electronic Word of Mouth (WOM), and .510 or 51.0% of the variance in Online Shopping Acceptance. Therefore, we assume that the structural model has a moderately predictive solid power to anticipate the structural relationships proposed between the study variables. Table 6 summarizes the outcomes of the Coefficients of Determination R2.

Table 6.

Coefficients of determination R2.

| S/R | Variables | R2 | Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Social Media Usage | .593 | Moderately Strong |

| 2. | Electronic Word of Mouth | .528 | Moderately Strong |

| 3. | Online Shopping Acceptance | .510 | Moderately Strong |

4.3.1. Hypotheses testing

In the second stage of assessing the structural model, we conducted the Path Analysis on IBM AMOS as suggested by the existing studies (Civelek, 2018; Dijkstra and Henseler, 2015; Henseler et al., 2015). It is notable that, along with the path values, the significance value indicating lower than 0.05, indicating a significant relationship between the study variables (Chepkirui and Huang, 2021). As summarized in Table 7 below, the relationship between Shopping Habits and Social Media Usage (t = 98.729, p > .000) and the relationship between Shopping Habits and Electronic Word of Mouth remained significant, with the t-value at 7.025 and significance value at p > .000. Besides, the relationship between Social Media Usage and Electronic Word of Mouth also remained significant (p > .000), indicating that our H2 is accepted.

Table 7.

Path analysis and P-value.

| Hyp. | Relationship | Path | t-value | Sign |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | S.H.S > SME | 1.057 | 98.729 | ∗∗∗ |

| H1b | SHS > WOM. | .299 | 7.025 | ∗∗∗ |

| H2 | SME > WOM. | .543 | 13.705 | ∗∗∗ |

| H3 | SME > OSA. | .340 | 3.621 | ∗∗∗ |

| H4 | WOM > OSA. | .644 | 5.666 | ∗∗∗ |

Note: SHS is Social Media Habits, SME is Social Media Usage, WOM is Word of Mouth, and OSA is online shopping acceptance.

Similarly, we found that the relationship between Social Media Usage and Online Shopping Acceptance (t = 3.621, p > .000) remained significant. On the other hand, the relationship between Electronic Word of Mouth and Online Shopping Acceptance remained significant at the t-value of 5.666 and the significance value at p > .000. Figure 4 below contains the path analysis of the Structural model.

Figure 4.

Path model of the study.

4.3.2. Mediation analysis

4.3.2.1. Mediating role of gender on the relationship between social media usage and online shopping acceptance

To assess the mediating role of gender on the proposed relationship between Social Media Usage and Online Shopping Acceptance, we conducted the mediation analysis on IBM AMOS (See Figure 2). According to MacKinnon et al. (2007), the mediation analysis is a practical assessment of how a third variable affects the relationship between two variables. This effect is determined by calculating the current project's mediation effect, as Yay suggested Yay (2017). Results first revealed that Social Media Usage has a significant direct impact on Online Shopping Acceptance, with the path value at .866 and t-value at 55.328 with the significance value at p > .000. Moreover, the path value of the relationship between Social Media Usage and Gender is .035, and the t-value at .203.

Similarly, the standardized Beta value of Gender and Online Shopping Acceptance remained at .018, with the t-value at .386. In this regard, we conducted the Sobel test to affirm the mediating role of gender on the relationship between proposed variables and found that, with the significance value at p > .000, we found a partial mediation effect of gender on the relationship between Social Media Usage and Online Shopping Acceptance (Standard Error= .015). Thus, results revealed that our H5a is accepted as Social Media Usage has both direct and indirect effects on Online Shopping Acceptance (See Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Mediation Analysis (part one).

4.3.2.2. Mediating role of gender on the relationship between electronic word of mouth and online shopping acceptance

Furthermore, to examine the mediating role of gender on the proposed relationship between Electronic Word of Mouth and Online Shopping Acceptance, we conducted the mediation analysis on IBM AMOS (See Figure 3) (MacKinnon et al., 2007; Yay, 2017). Results first revealed that the Electronic Word of Mouth directly affects Online Shopping Acceptance with a path value of 1.05 and a t-value of 57.087. The significance value at p > .000. Moreover, the relationship between Electronic Word of Mouth and Gender also remained significant, with the path value at .041 and the t-value at .038. and .288 (respectively). Finally, regarding the relationship between Gender and Online Shopping Acceptance, the path value remained at .005, the t-value at .120, and the significance value 0.000 (indirect value = .043), indicating a partial mediation effect of gender on the relationship between Social Media Usage and Online Shopping Acceptance. Thus, results revealed that our H5b is accepted as Electronic Word of Mouth has direct and indirect effects on Online Shopping Acceptance (See Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Mediation Analysis (part two).

5. Discussion

According to Cheema et al. (2014), technology-centered online shopping lets customers personally visit stores virtually and decide after observing the products' compatibility and standard. Here, reviews and comments from other consumers play an essential role in making a favorable decision.

Similarly, this study witnessed the role of two factors, including Social Media Usage and Electronic Word of Mouth (WOM). First, we found these two factors strongly affected online shopping acceptance through the previous studies and later the study results. In his regard, we first found shopping habits to be strongly associated with social media usage with a significance value of p > .000∗∗∗. These results show remarkable consistency with the study by Paquette (2013). The researcher argued that micro and macro-level retailers worldwide prefer online platforms to promote their products and shop for them in a virtual environment. As a result, we can find a significant relationship between social media usage and online shopping acceptance. Moreover, the relationship between shopping habits and Electronic Word of Mouth (WOM) is also consistent (p > .000∗∗∗) with the arguments given by Harun & Omar, (2017). It is noted that making products or services online is now more influential than traditional marketing and providing the products in physical stores. Tactics like Search Engine Optimized keywords, blog posts, YouTube-based advertising that also contains direct links to online stores, and even Facebook, Pinterest, Twitter, and Instagram-based official pages are means by which an individual can access products or services they want to purchase. Besides, this accessibility also [provides direct exposure to the experiences and opinions of other consumers that have shared negative or positive views about the relevant product. Interestingly, as noted by Shashikala & DK, (2021), word of mouth has more substantial effects on one's buying intentions than any other factor. Especially Electronic Word of mouth is more powerful than traditional word of mouth is now fast, directly accessible, openly observable, and has a relevant impact on one's buying intentions.

Furthermore, the relationship between social media usage and online shopping acceptance is also validated with a significance value of p > .004∗∗. These results also strongly correlated with the existing studies conducted in different geographical regions (Arul Jothi and Mohmadraj Gaffoor, 2017; Dwivedi et al., 2021; Taha et al., 2021; Zinko et al., 2021). They also affirmed negative and positive word of mouth (WOM) on consumers' online shopping acceptance. Notably, the study respondents widely agreed that they use social media for online shopping. Yet Electronic Word of mouth remained an equally significant phenomenon that helped shape their shopping decisions (Putra et al., 2020).

Likewise, the mediating role of gender on the relationship between social media usage and online shopping role remained enormously significant. This relationship is also validated by Sánchez Sánchez Torres et al., (2018), as they argued that individual differences based on gender and other demographics are highly influential on online shopping acceptance. This gender difference does not mean a particular gender is more lenient and interested in online shopping. However, it depends on different factors, i.e., personal interest, consideration, and others. Instead, it is inevitable based on the geographical regions. This proposition is significant in the current study as Emirati online consumers vary based on gender. Finally, the second proposition (H5b), assuming the mediating effect of gender on the relationship between Electronic Word of mouth and online shopping acceptance, also remained enormously significant. Once again, the Emirati online consumers from Al Ain city affirmed substantial gender differences based on the Electronic Word of mouth for online shopping acceptance. These results are also compatible with the argumentation by Selvi & Thomson (2016) in their study about the role of gender in considering Electronic Word of Mouth for making online purchase decisions. As stated, the arrival of social media and its usage for decision-making is not apart from the influences of gender. Those who want to purchase the products through online retailers prefer to check what existing consumer say about their experiences, which further help them to make the decision accordingly (Anastasiei and Dospinescu, 2019; Ismagilova et al., 2019; Lăzăroiu et al., 2020; Zhenquan and Xueyin, 2019).

5.1. Study limitations

Although we have made every possible effort, this study has certain limitations. First, the current research involved gender as a mediating variable. At the same time, other demographics, such as age and qualification level, could strongly impact the proposed relationships between the variables. Second, the generalizability of results geographically also adds to its limitation. Finally, the third limitation involves the rejection of Hypotheses 2 and 5b, which can be validated if the same study model is executed in some other geographical location or with the other demographical variables. However, despite the limitations, we also recommend more studies, especially by using other demographic factors as mediating variables, as analyzing further and validate the role of demographics on online shopping acceptance and behavior.

6. Conclusions

Our study analyzed the role of social media usage and Electronic Word of mouth (WOM) on online shopping acceptance and further mediating impacts of gender on the proposed relationships. This study significantly provides in-depth insights regarding the role of gender in the online shopping decision-making process that will guide online e-consumers, future researchers, and sellers to consider gender as an influential factor. Moreover, we used a self-proposed study model and examined it accordingly. Proposing a study model and applying Structural Equation Modelling adds more to the literature regarding online shopping acceptance factors. Besides, the self-proposed study model validated by the Structural Equation Modelling also provides a baseline for future studies to examine the role of gender and other demographics in online shopping acceptance. Thus, online retails are a strategic source of increasing e-commerce, primarily facilitated by worldwide social media. Mainly, in a country like the United Arab Emirates, these retail stores provide high-standard products, as the Emirati market is one of the world's brightest business arenas. The multicultural nature of the public, economic solid resources, and the government's efforts to provide the public with possibly high-quality life further attract the world's largest brands to approach and gain consumer loyalty. As a result, the Emirati public and people from Al-Ain city primarily rely on online shopping. For this purpose, they consider different factors and their demographical factor, i.e., gender, as highly influential on their online shopping acceptance.

6.1. Practical implications

According to James and their colleagues (James et al., 2019), integrating marketing communication messages in an online environment is a strong consideration for contemporary marketers. However, accelerating their impacts and increasing consumers' acceptance is a primary consideration. A platform containing comments from existing consumers is an important element contributing to the sales and growth of a business. In other words, Electronic Words of Mouth have a strong ability to increase sales and, eventually, brand images among consumers. Attracting new consumers, motivating them to purchase, and benefiting from their positive comments are important today. In this regard, this study provides certain practical implications to Emirati marketers that may enhance their product exposure, leading to a positive buyer response. First, Emirati marketers must integrate improved technology such as Artificial Intelligence to enhance consumers' overall shopping experiences. Second, special consideration to product suggestions should also be given, providing more relevant suggestions will positively influence their opinion about the shopping services. Finally, consumer surveys should be consistently conducted, which will further help to determine their needs leading to product improvement and positive opinions towards the products and services.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Riadh Jeljeli, Ph.D; Faycal Farhi, Ph.D: Conceived and designed the research; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Mohamed Elfateh Hamdi, Ph.D: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Ab Hamid M.R., Sami W., Mohmad Sidek M.H. Discriminant validity assessment: use of Fornell & larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. J. Phys. Conf. 2017;890(1) [Google Scholar]

- Abir T. Electronic Word of Mouth (e-WOM) and consumers’ purchase decisions: evidences from Bangladesh. J. Xi'an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2020;XII(III):367–382. [Google Scholar]

- Abir T., Muhammad D., Yazdani N.A., Bakar A., Hamid A. 2020. Electronic Word of Mouth (E- WOM) and Consumers ’ purchase Decisions: Evidences from Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed R.R., Streimikiene D., Berchtold G., Vveinhardt J., Channar Z.A., Soomro R.H. Effectiveness of online digital media advertising as a strategic tool for building brand sustainability: evidence from FMCGs and services sectors of Pakistan. Sustainability. 2019;11(12) [Google Scholar]

- Albarq A.N., Doghan M. Al. Electronic word-of-mouth versus word-of-mouth in the field of consumer behavior: a literature review. J. Crit. Rev. 2020;7(July):646–654. [Google Scholar]

- Alghizzawi M., Habes M., Salloum S.A., Ghani M.A., Mhamdi C., Shaalan K. The effect of social media usage on students’ e-learning acceptance in higher education: a case study from the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Lang. Stud. (IJITLS) 2019;3(3):13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Alhawamdeh A.K., Alghizzaw M., Habes M., Alshibly M.S. 2020. The Relationship between Media Marketing Advertising and Encouraging Jordanian Women to Conduct Early Detection of Breast Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- Ali S., Qamar A., Derindag O.F., Habes M., Youssef E. He mediating role of gender in ICT acceptance & its impacts on students’ academic performance during covid-19. Int. J. Adv. Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. 2021;10(2):505–514. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiei B., Dospinescu N. Electronic word-of-mouth for online retailers: predictors of volume and valence. Sustainability. 2019;11(3) [Google Scholar]

- Appel G., Grewal L., Hadi R., Stephen A.T. The future of social media in marketing. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2020;48(1):79–95. doi: 10.1007/s11747-019-00695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arul Jothi C., Mohmadraj Gaffoor A. Impact of social media in online shopping. ICTACT J. Manag. Stud. 2017;3(3):576–586. [Google Scholar]

- Babić Rosario A., de Valck K., Sotgiu F. Conceptualizing the electronic word-of-mouth process: what we know and need to know about eWOM creation, exposure, and evaluation. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2020;48(3):422–448. [Google Scholar]

- Bilal M., Jianqiu Z., Dukhaykh S., Fan M., Trunk A. Understanding the effects of ewom antecedents on online purchase intention in China. Information. 2021;12(5):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chang J. Online Shopping: Advantages over the Offline Alternative. 2015. Online shopping: advantages over the offline alternative; pp. 2000–2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudary S., Nisar S., Abdul M. Vol. 1. 2014. Factors influencing the acceptance of online shopping in Pakistan; pp. 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cheema U., Jalal R., Rizwan M. The trend of online shopping in 21 ST century : IMPACT of enjoyment in tam model Muhammad Rizwan Rizwan Jalal faiza Durrani Nawal sohail online shopping. Asian J. Empir. Res. 2014;3(2):131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Chepkirui J., Huang W. A path analysis model examining self-concept and motivation pertinent to undergraduate academic performance: a case of Kenyan public universities. Educ. Res. Rev. 2021;16(3):64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chung C., Muk A. Online shoppers’ social media usage and shopping behavior. Proc. Acad. Market. Sci. 2017;1:675. Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- Civelek M.E. Zea Books; 2018. Essentials of Structural Equation Modeling. [Google Scholar]

- Dada M.H. Impact of brand association, brand image & brand loyalty on brand equity. J. Market. Strateg. 2021;3(1):29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Davis J.B. Word of mouth. ABA Journal. 2002;88(MAR./JUL):26–27. [Google Scholar]

- De Sá Medeiros H., Paes de Souza M., Paiva Maciel L.A. Word-of-Mouth communication in the online purchasing decision process. Sustainable Business International Journal. 2019;83 [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra T.K., Henseler J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q.: Manag. Inf. Syst. 2015;39(2):297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y.K., Ismagilova E., Hughes D.L., Carlson J., Filieri R., Jacobson J., Jain V., Karjaluoto H., Kefi H., Krishen A.S., Kumar V., Rahman M.M., Raman R., Rauschnabel P.A., Rowley J., Salo J., Tran G.A., Wang Y. Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: perspectives and research propositions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021;59 [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y.K., Rana N.P., Slade E.L., Singh N., Kizgin H. Editorial introduction: advances in theory and practice of digital marketing. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2020;53 [Google Scholar]

- East R., Romaniuk J., Chawdhary R., Uncles M. The impact of word of mouth on intention to purchase currently used and other brands. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2017;59(3):321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo Filho D.B., Silva Júnior J.A., Rocha E.C. What is R2 all about? Leviathan. 2011;3:60. [Google Scholar]

- Global Media Insight . 2021. UAE Social Media Usage Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Habes M., Alghizzawi M., Ali S., Salihalnaser A., Salloum S.A. The Relation among Marketing ads, via Digital Media and mitigate (COVID-19) pandemic in Jordan. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020;29(7):12326–12348. [Google Scholar]

- Habes M., Ali S., Anwar S. Statistical package for social sciences acceptance in quantitative research: from the technology acceptance Model’s perspective. FWU J. Soc. Sci. 2021;15(4) [Google Scholar]

- Hanekom J. PR. November; 2006. A Theoretical Framework for the Online Consumer By Janette Hanekom Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master Of Arts in the Subject Communication at the University of South Africa Supervisor : Prof R Barker Joint Supervisor. [Google Scholar]

- Harun A., Omar S.S. first ed. Pernerbit UTHM; 2017. Words of Mouth (WOM) and its Impacts on Consumer Behavior: Brand Equity Perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2015;43(1):115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper D., Coughlan J., Mullen M.R. Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods. 2008;6(1):53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain Md.M., Kabir S., Rezvi R.I. Influence of word of mouth on consumer buying decision: evidence from Bangladesh market. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2017;9(12):38–45. [Google Scholar]

- In’nami Y., Koizumi R. Review of sample size for structural equation models in second language testing and learning research: a Monte Carlo approach. Int. J. Test. 2013;13(4):329–353. [Google Scholar]

- International K. 2017. The Truth about Online Consumers. [Google Scholar]

- Ismagilova E., Slade E.L., Rana N.P., Ismagilova E., Slade E., Rana N.P., Dwivedi Y.K. The Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth Communications on Intention to Buy: University of Bristol—Explore Bristol Research the Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth Communications. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019;1–24 [Google Scholar]

- James D., Lee J., Wheeler K. Theory and application. SpringerBriefs in Appl. Sci. Technol. 2019:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Song J. The quality of word-of-mouth in the online shopping mall. J. Res. Indian Med. 2010;4(4):376–390. [Google Scholar]

- Kılıç Z., Ateş V. 5th International Management Information Systems Conference; 2018. An Investigation of Online Shopping Habits of University Students: Gaziantep Province Case. [Google Scholar]

- Lăzăroiu G., Popescu G.H., Nica E. The role of electronic word-of-mouth in influencing consumer repurchase intention in social commerce. SHS Web of Conf. 2020;74 [Google Scholar]

- Lim Y.M., Cheng B.L., Cham T.H., Kar C., Ng Y., Tan J.X. Gender differences in perceptions and attitudes toward online shopping: a study of Malaysian consumers. J. Market. Adv. Pract. 2019;1(2):11–24. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D.P., Fairchild A.J., Fritz M.S. Mediation analysis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour O., Farmanesh P. Does gender matter? Acceptance and forwarding of electronic word of mouth: a moderated mediation analysis. Manag. Sci. Letters. 2020;10(7):1481–1486. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta S., Bansal S., Bagga T. Social Media and online shopping-are the choices swayed? A youth perspective. Int. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. Res. 2017;15(1):21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mello S. C. B. de, Collins M. Convergent and discriminant validity of the perceived risk scale in business-to-business context using the multitrait-multimethod approach. Rev. Admin. Contemporânea. 2001;5(3):167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Mohajan H.K. Annals of Spiru Haret University. Economic Series. Vol. 17. 2017. Two criteria for good measurements in research: validity and Reliability; pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Nuseir M.T. The impact of electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) on the online purchase intention of consumers in the Islamic countries – a case of (UAE) J. Islamic Market. 2019;10(3):759–767. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette H. University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Major; 2013. Social media as a Relationship Marketing Tool of Modern university. [Google Scholar]

- Pham V.K., Do Thi T.H., Ha Le T.H. A study on the COVID-19 awareness affecting the consumer perceived benefits of online shopping in Vietnam. Cog. Bus. Manag. 2020;7(1) [Google Scholar]

- Pradhana F., Sastiono P. Vol. 72. Icbmr; 2019. Gender Differences in Online Shopping: Are Men More Shopaholic Online? pp. 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Putra T.R.I., Ridwan, Kalvin M. How electronic word of mount (E-Wom) affects purchase intention with brand image as A mediation variable: case of xiaomi smartphone in student. J. Phys. Conf. 2020;1500(1) [Google Scholar]

- Rafiq M.Y., Javeid U. Impact of gender difference on online shopping attitude of university students. SSRN Electron. J. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E.M., Singhal A., Quinlan M.M. An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research. third ed. 1962. Diffusion of innovations. [Google Scholar]

- Salloum S.A., Al-Emran M., Habes M., Alghizzawi M., Ghani M.A., Shaalan K. Understanding the impact of social media practices on E-learning systems acceptance. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2020;1058(August 2020):360–369. [Google Scholar]

- Salloum S.A., Al-Emran M., Khalaf R., Habes M., Shaalan K. An innovative study of e-payment systems adoption in higher education: theoretical constructs and empirical analysis. Int. J. Interact. Mobile Technologies. 2019;13(6):68–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Torres J.A., Cañada F.J.A., Moro M.L.S., Irurita A.A. Impact of gender on the acceptance of electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) information in Spain. Contaduría Adm. 2018;63(4) [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt M., Ringle C.M., Hair J.F. Handbook of Market Research (Issue September) 2020. Handbook of market research. [Google Scholar]

- Sayani H., Trust Z. 2019. Online Shopping: Exploring Perceptions of Digital Natives in the United Arab Emirates. [Google Scholar]

- Selvi B.N.M., Thomson J.E. An exploratory study on the electronic word of mouth communication in promoting brands in the online platforms. Intell. Inf. Manag. 2016;8(5):115–141. [Google Scholar]

- Setia M.S. Methodology series module 3: cross-sectional studies. Indian J. Dermatol. 2016;61(3):261–264. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.182410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashikala E.D.T., Dk T. Impact of electronic word of mouth on consumer purchase intention in fast food industry: a conceptual review with special reference to Facebook users. SSRN Electron. J. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Eder L. Determining factors in the acceptance of social shopping websites. 15th Americas Conf. Inf. Syst. 2009, AMCIS 2009. 2009;3:2123–2131. [Google Scholar]

- Stenger T. 2016. Online Shopping Experiences: A Qualitative Research. [Google Scholar]

- Sulthana A.N., Vasantha S. Influence of electronic word of mouth eWOM on purchase intention. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2019;8(10):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Svatosova V. Vol. 12. 2020. The Importance of Online Shopping Behavior in the Strategic Management of E-Commerce Competitiveness; pp. 143–160. [Google Scholar]

- Taha V.A., Pencarelli T., Škerháková V., Fedorko R., Košíková M. The use of social media and its impact on shopping behavior of Slovak and Italian consumers during COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability. 2021;13(4):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira S., Martins J., Branco F., Gonçalves R., Au-Yong-Oliveira M., Moreira F. A theoretical analysis of digital marketing adoption by startups. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2018;688:94–105. [Google Scholar]

- Visa Confidential U.A.E. 2020. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) eCommerce Landscape 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Voramontri D., Klieb L. Impact of social media on consumer behaviour. Int. J. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2019;11(3):209–233. [Google Scholar]

- Vynogradova O., Drokina N., Yevtushenko N., Darchuk V., Irtlach M. Theoretical approaches to the definition of Internet marketing: Ukrainian dimension. Innovat. Market. 2020;16(1):89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Waghchoure M., Walunj P. Vol. 14. 2021. Impact of social media usage on consumer behavior; pp. 2067–2078. [Google Scholar]

- Wong K.K.-K. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Market. Bull. 2013;24(1):1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Lee M.J. Shopping as a social activity: understanding people’s categorical item sharing preferences on social networks. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2018:2068. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Wang Y., Khan A., Zhao R. Vol. 12. 2021. Consumer flow experience of senior citizens in using social media for online shopping; pp. 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen S., Jusoh N. The impacts of electronic word of mouth in social media on consumers’ purchase intentions. Elem. Educ. Online. 2021;20(4):850–857. [Google Scholar]

- Yay M. The mediation analysis with the Sobel test and the percentile bootstrap. Int. J. Manag. Appl. Sci. 2017;3(2):2394–7926. [Google Scholar]

- Zhenquan S., Xueyin X. 7th International Conference on Innovation & Management; 2019. 264 the Processes of Online Word-Of-Mouth on the Purchase Decision; pp. 2033–2036. [Google Scholar]

- Zinko R., Patrick A., Furner C.P., Gaines S., Kim M.D., Negri M., Orellana E., Torres S., Villarreal C. Responding to negative electronic word of mouth to improve purchase intention. J. Theoret. Appl. Elect. Comm. Res. 2021;16(6):1945–1959. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.