Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the pre-mRNA leakage 39-kDa protein (ScPml39) was reported to retain unspliced pre-mRNA prior to export through nuclear pore complexes (NPCs). Pml39 homologs outside the Saccharomycetaceae family are currently unknown, and mechanistic insight into Pml39 function is lacking. Here we determined the crystal structure of ScPml39 at 2.5 Å resolution to facilitate the discovery of orthologs beyond Saccharomycetaceae, e.g. in Schizosaccharomyces pombe or human. The crystal structure revealed integrated zf-C3HC and Rsm1 modules, which are tightly associated through a hydrophobic interface to form a single domain. Both zf-C3HC and Rsm1 modules belong to the Zn-containing BIR (Baculovirus IAP repeat)-like super family, with key residues of the canonical BIR domain being conserved. Features unique to the Pml39 modules refer to the spacing between the Zn-coordinating residues, giving rise to a substantially tilted helix αC in the zf-C3HC and Rsm1 modules, and an extra helix αAB′ in the Rsm1 module. Conservation of key residues responsible for its distinct features identifies S. pombe Rsm1 and Homo sapiens NIPA/ZC3HC1 as structural orthologs of ScPml39. Based on the recent functional characterization of NIPA/ZC3HC1 as a scaffold protein that stabilizes the nuclear basket of the NPC, our data suggest an analogous function of ScPml39 in S. cerevisiae.

Subject terms: X-ray crystallography, Proteins

Introduction

Nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) are large macromolecular assemblies (MW of ~ 60 MDa in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and mediate the transport of a tremendous range of cargoes such as water, ions, small molecules, proteins, and ribonucleoparticles across the nuclear envelope1–4. As exclusive transport channels between the nucleus and cytoplasm, NPCs are ideally positioned to serve as gateways or checkpoints in the flow of information from DNA to protein and have therefore long been postulated to function in “gene gating”5. NPCs indeed play key roles beyond nucleocytoplasmic transport, such as in genome organization and integrity, gene regulation, and mRNA quality control (QC)6–12.

The mRNA QC ensures that incompletely processed and/or improperly assembled mRNA ribonucleoparticles (mRNPs) are discarded to avoid detrimental effects on protein homeostasis or RNA metabolism13,14. This processing status and export competency of mRNPs can be monitored through their association with the nuclear basket, which is envisioned to serve as a platform to which mRNPs transiently associate prior to nuclear export to the cytoplasm11,15–19. For example, the poly(A)-binding protein ScNab2, which directly binds to the C-terminal region of Myosin-like protein 1 (ScMlp1) of the nuclear basket, monitors proper 3′-mRNA processing15,20–22. In turn, ScMlp1 deletion triggers cytoplasmic leakage of intron-containing pre-mRNAs23. A similar role in the nuclear retention of unspliced reporter mRNAs in vivo was assigned to homologs in fission yeast (SpNup211) and mammals (Tpr)24–26. Furthermore, a pre-mRNA leakage phenotype was observed for the deletion of an ScMlp1/ScMlp2-interacting protein termed S. cerevisiae pre-mRNA leakage protein 39-kDa (ScPml39)27. Conversely, its overexpression traps intron-containing mRNAs in nuclear foci enriched in ScMlp1 and ScNab227. ScPml39 is required for cell growth in the absence of a functional Y-complex, an essential NPC building block required for mRNA export28,29, and is recruited to the nuclear basket of NPCs by virtue of interactions with the N-terminal regions of ScMlp1 and ScMlp227. While ScMlp1/2 and ScNab2 sequences and functions are highly conserved across phyla11,21,30, the ScPml39 sequence is unique to Saccharomycetaceae (Fig. S1). To date, no homologous sequences could be found in human, S. pombe, and others. Thus, identifying orthologs in organisms beyond Saccharomycetaceae would accelerate our understanding of the function of ScPml39.

As form follows function, determining the atomic structure of ScPml39 and identifying key residues involved in its structural integrity is a course of action to find ScPml39 orthologs31. The structure prediction programs Phyre2 and SWISS-MODEL32,33 identified two Baculoviral Inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) Repeat (BIR) domains in ScPml39. BIR domains contribute to protein–protein interactions in both apoptotic34–38 and non-apoptotic pathways39–41. The canonical BIR domain is well-studied, with currently 312 structures available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), including structures in complex with substrate peptides. Their structures are highly conserved, as illustrated by a root-mean square deviation (RMSD) of Cα atoms of less than 1.0 Å for the representative BIR domains human neuronal apoptosis inhibitor protein (PDB: 2VM5), human Survivin (PDB: 3UED), and D. melanogaster IAP1-BIR1 (Fig. S2b)42. The BIR domain is comprised of ~ 70 amino acid residues, three α-helices (αA, αB, and αC) and one β-sheet formed by three anti-parallel strands (β1, β2, and β3). The BIR domain harbors a cysteine-cysteine-histidine-cysteine (CCHC)-type zinc finger (ZnF) motif with the consensus sequence Rxx(S/T)Ω…GΩ…C-x2-C-x16-H-x6-C-x-Ω (x denotes any amino acid residue and Ω an aromatic residue) (Fig. S2a). The importance of the conserved residues for structural integrity was previously noted43. In particular, the motif Rxx(S/T)Ω is located in helix αA, and the Arg residue is essential. The motif GΩ is located between αB and β1 to form a sharp β-turn. The first and second Zn-coordinating cysteine are in the loop between β2 and β3, the Zn-coordinating histidine is in helix αC, and the last Zn-coordinating cysteine is in the loop between helices αC and αD. The final aromatic residue Ω is located in helix αD to undergo π–cation interactions with Arg in the Rxx(S/T)Ω motif of helix αA (Fig. S2a).

In ScPml39, the two potential ZnF motifs deviate from the consensus sequence by a shortened linker between the Zn-coordinating histidine and cysteine residues: C-x2-C-xn-H-x3-C. This difference is a hallmark of the zf-C3HC (ID: PF07967) and Rsm1 (ID: PF08600) protein families, which together with the canonical BIR domain (ID: PF00653) comprise the CCHC ZnF motif-containing clan of BIR-like domains (ID: CL0417) according to the Pfam database44. ScPml39 is predicted to have two zfC3HC and/or Rsm1 domains. In contrast to the canonical BIR and zf-C3HC domains, the Rxx(S/T)Ω motif could not be identified in the Rsm1 family by a Hidden Markov model (HMM)45 (Fig. S3). Furthermore, although the zfC3HC and Rsm1 domains are widely distributed in 1897 sequences from 1208 species and 1155 sequences from 896 species in the Pfam database, respectively, a structure of these domains is currently not available in the PDB. Since the spacing between the ZnF-coordinating residues is critical for ZnF structure and function46, we set out to determine the crystal structure of ScPml39 to assess the impact of the ZnF motif differences on the zf-C3HC and Rsm1 domains.

Here we present the 2.5 Å-resolution crystal structure of ScPml39 and identify orthologs in S. pombe and human based on structure-guided sequence alignment. The distinct spacing between the CCHC ZnF-coordinating residues results in features that are different from the canonical BIR domain. Two zf-C3HC and Rsm1 modules tightly associate to form a novel “Pml39 fold”.

Results

ScPml39 contains a single domain that recapitulates subcellular localization, function, and ScMlp1-interaction of full-length ScPml39

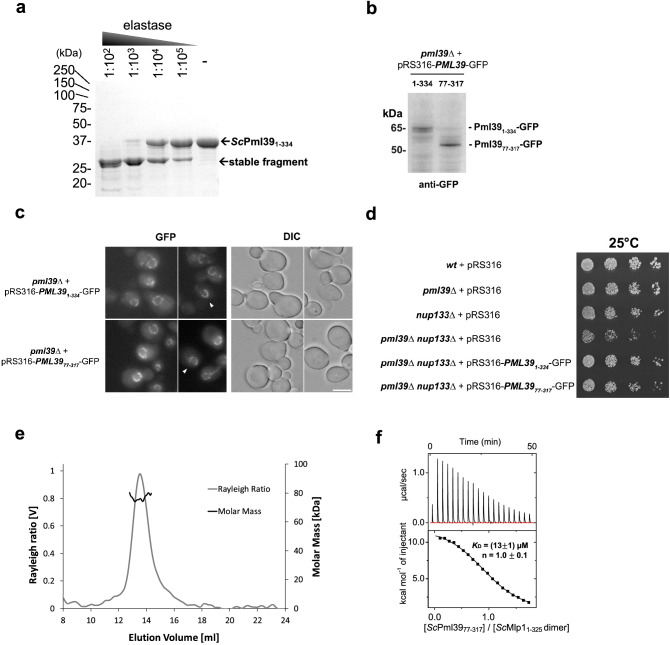

The domain structure of ScPml39 was determined by limited proteolysis using the full-length recombinant protein ScPml39 (residues 1–334). Elastase digest yielded a stable single fragment of ~ 30 kDa molecular weight (Fig. 1a). Based on the domain boundaries identified by mass spectrometry, we generated a truncated ScPml39 construct comprising residues 77–317 for structural studies. Notably, ScPml3977–317 is a functional domain fragment both in vitro and in vivo. In yeast cells, GFP-tagged ScPml3977–317 expressed in pml39Δ mutant yeast cells was recruited to the NPC nuclear basket and displayed the typical U-shaped perinuclear staining as the wild type (Fig. 1b,c)27. Expression of ScPml3977–317-GFP and full-length ScPml39-GFP similarly complemented the synthetic growth defect arising from the simultaneous loss-of-function of ScPml39 and of the Y-complex (nup133∆) (Fig. 1d). In vitro, ScPml3977–317 maintains direct binding to a recombinant homodimer of N-terminal fragment of ScMlp1 (residues 1–325) with a dissociation constant (KD) of ~ 13 µM and a 1:1 molar ratio, as measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (Fig. 1e,f).

Figure 1.

ScPml39 contains a single domain that recapitulates subcellular localization, function, and ScMlp1-interaction of full-length ScPml39. (a) Limited proteolysis of recombinant full-length ScPml39 at the indicated dilutions of 2 mg/ml elastase analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The full-length version of the cropped gel is presented in Fig. S4a. (b) Expression of GFP-tagged full-length (1–334) or truncated (77–317) versions of ScPml39 in pml39Δ cells detected by immunoblotting using anti-GFP antibodies. The full-length version of the cropped blot is presented in Fig. S4b. (c) Live imaging of pml39Δ cells expressing GFP-tagged full-length (1–334) or truncated (77–317) versions of ScPml39. Single plane images are shown for the GFP and DIC (differential interference contrast) channels. Arrowheads point to nuclei showing the U-shaped perinuclear staining typical of ScPml39. Scale bar, 5 µm. (d) Cells of the indicated genotypes were spotted as serial dilutions on SC medium and grown for 3 days at 25 °C. (e) Recombinant ScMlp11–325 forms a homodimer. Size exclusion chromatography coupled to multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) using a Superdex 200 10/300 column was used. Molecular mass determination and Rayleigh ratio of ScMlp11–325 (dark and light gray, respectively) demonstrated that the ScMlp11–325 (expected molecular size is 41 kDa) has a dimeric size (~ 80 kDa). (f) Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) thermogram (upper panel) and plot of corrected heat values (lower panel) showed that monomeric ScPml3977–317 binds dimeric ScMlp11–325 at a 1:1 molar ratio with a KD value of ~ 13 μM.

ScPml3977-317 contains two tightly interacting BIR-like Rsm1 and zf-C3HC modules

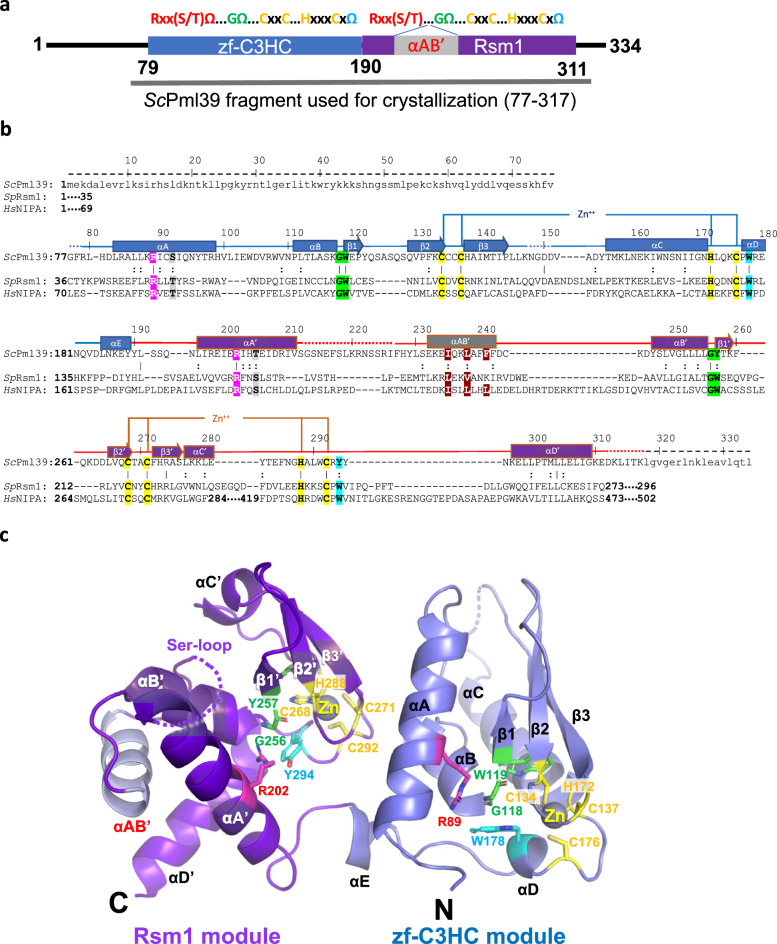

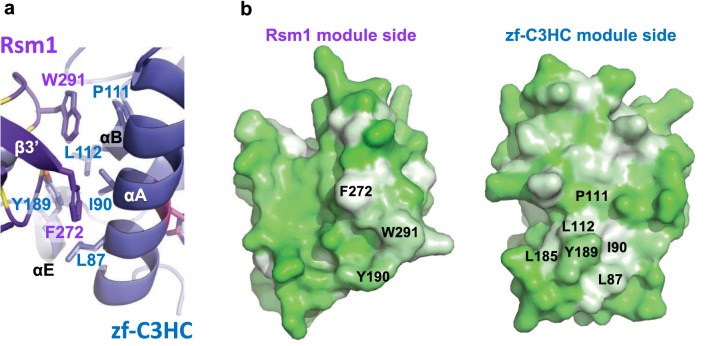

ScPml3977–317 was crystalized in the P3121 space group. The phases and the structure were determined to a resolution of 2.5 Å by Zinc single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (Zn-SAD) (Table 1 and Fig. S5). The crystallographic asymmetric unit contains one molecule. The majority of the fragment (residues 79–311, Fig. 2a) was well resolved in the electron density, while no electron density was observed for two N-terminal residues (77–78), residues 148–151 between β3 strand and helix αC, a Ser-rich region comprising residues 213–226, and six C-terminal residues (312–317, Fig. 2b). ScPml3977–317 contains two BIR-like modules: zf-C3HC (residues 79–189 in blue) and Rsm1 (residues 190–311 in purple) (Fig. 2b,c). The two zf-C3HC and Rsm1 modules form a single structural domain stabilized by the hydrophobic residues Leu87, Ile90, Pro111, Leu112, Leu185, Tyr189 of zf-C3HC and Tyr190, Phe272, and Trp291 of Rsm1 (Fig. 3). Each module could not be expressed individually as a soluble protein in E. coli (data not shown), consistent with the limited proteolysis data (Fig. 1a).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Data collection | |

| Beamline | 8.2.2 (ALS) |

| Space group | P3121 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | a = 53.0, b = 53.0, c = 171.3 |

| α, β, γ (°) | α = β = 90, γ = 120 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.282 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 44.34–2.49 (2.58–2.49) |

| No. of unique reflections | 18,841 (1837) |

| Rmerge (%)a,b | 4.5 (88.9) |

| CC1/2a | 1 (0.954) |

| CC*,a | 1 (0.988) |

| c | 30.4 (3.2) |

| Completeness (%)a | 99.6 (99.7) |

| Redundancyb | 11.3 (11.4) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 44.34–2.49 |

| No. of reflections | 18,812 |

| Test set | 941 |

| Rworkd/Rfreee (%) | 23.3/26.3 |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 1779 |

| Zn | 2 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.003 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.49 |

| (Å2) | |

| Protein | 97.0 |

| Zn | 80.6 |

| Ramachandran plotf | |

| Favored (%) | 98.1 |

| Allowed (%) | 1.9 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.0 |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 0 |

| Clashscore | 4.2 |

| Cβ deviation | 0 |

| PDB | 7RDN |

aHighest-resolution shell is shown in parentheses.

bRmerge = Σ | I − | / ΣI, where I is the observed intensity and is the averaged intensity from multiple observations.

c = averaged ratio of the intensity (I) to the error of the intensity (σI).

dRwork = Σ | Fobs − Fcal | /Σ | Fobs |, where Fobs and Fcal are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

eRfree was calculated using a randomly chosen subset (5%) of the reflections not used in refinement.

fAs determined by MolProbity.

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of ScPml3977–317. (a) Schematic of ScPml39. The consensus sequence of the zf-C3HC and Rsm1 modules is shown on the top. The zf-C3HC and Rsm1 modules are indicated in blue and purple, respectively. The fragment used for crystallization (residues 77–317) is shown. (b) Structure-guided sequence alignment of ScPml39, SpRsm1 and human NIPA/ZFC3HC1. αA–αE refer to α-helices, and β1–β3 to β-strands, indicating the secondary structure elements of ScPml39. Residue numbering is shown for ScPml39. Residues highlighted designate conserved Arg (magenta) and Ser/Thr (gray) in αA, Gly-aromatic residues between αB and β1 (green), conserved zinc-coordinating residues (yellow), a conserved aromatic residue in αD or in the loop αC'-αD' (cyan), and conserved hydrophobic residues in αAB' (brown). Similar and identical residues are marked as : and |, respectively. Disordered regions are represented by dotted lines, whereas regions lacking in the crystallization fragment are indicated by dashed lines and lowercase letters. (c) The Pml39 fold (cartoon representation) and side chains of key residues (stick representation) are shown.

Figure 3.

Hydrophobic interface between zf-C3HC and Rsm1 modules. (a) Residues involved in van der Waals’ contacts are shown in stick representation. (b) Hydrophobicity of Rsm1 and zf-C3HC module are shown using PyMOL script color_h, ranging from white (highly hydrophobic) to green (less hydrophobic).

Structure of the zf-C3HC module of ScPml39

The ScPml39 zf-C3HC module comprises five α-helices (αA (83–98), αB (111–117), αC (156–171), αD (177–180), and αE (185–189)) and one antiparallel β-sheet composed of three strands (β1 (119–121), β2 (129–134), and β3 (138–144)) (Fig. 2; Fig. S6). Arg89 and Ser92 in helix αA are part of the conserved Rxx(S/T)Ω consensus motif. The guanidinium group of Arg89 interacts with the aromatic ring of Trp178 in helix αD, as observed in canonical BIR domain proteins (Fig. 4b). A 12-residue loop (His99 to Asn110) connects the helices αA and αB. Gly118 forms a sharp turn and connects helix αB and strand β1. The adjacent aromatic residue Trp119 is part of an invariant GΩ dipeptide motif present in the canonical BIR domains36,43,47. Trp119 and Met141 in the strand β3 engage in a sulphur-aromatic interaction, and an internal hydrophobic network within the β-sheet, helices αB, αD, and αC stabilizes the zf-C3HC module (Fig. 4c). While these characteristics classify the zf-C3HC domain as a member of the BIR-like family, the CCHC ZnF motif is different both in sequence and in structure from the canonical BIR domain (Fig. S2). Cys134, Cys137, His172, and Cys176 residues coordinate Zn to form the C-x2-C-x–H-x3-C ZnF motif (Fig. 2c). The three residues between His172 and Cys176 represent a unique signature of zf-C3HC domain proteins, in contrast to six residues in canonical BIR domain proteins (Figs. S1, S2). Furthermore, the presence of 34 residues between Cys137 and His172 in Pml39 zf-C3HC module, compared to 16 residues in canonical BIR domains, results in an elongated zf-C3HC module comprising ~ 110 residues versus ~ 70 residues in most canonical BIR domains36,48,49.

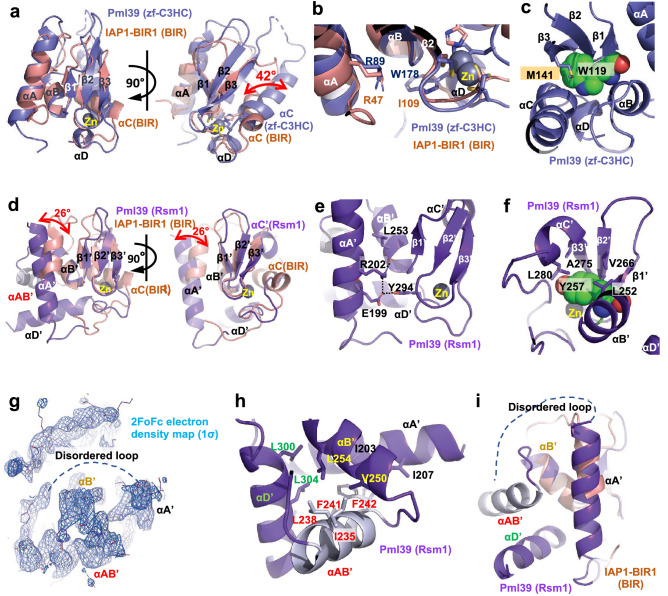

Figure 4.

Structure of ScPml39 modules. (a) Superimposition of ScPml39 zf-C3HC module (in blue) and a representative canonical BIR domain, D. melanogaster IAP1-BIR1 domain structure (in orange, PDB: 3SIP) (left panel) and a view rotated by ~ 90° (right panel). (b) Structural conservation of Arg89 in helix αΑ and Trp178 in helix αD. (c) Internal hydrophobic network in ScPml39 zf-C3HC module. (d) Superimposition of ScPml39 Rsm1 module (in purple) and a representative canonical BIR domain, D. melanogaster IAP1-BIR1 domain structure (in orange, PDB: 3SIP) (left panel) and a view rotated by ~ 90° (right panel). (e) Structural conservation of Arg202 in helix αΑ′ and Tyr294 in helix αD′. (f) Internal hydrophobic network in ScPml39 Rsm1 module. (g) 2FoFc electron density, contoured at 1σ above the mean for helix αAB′ in Rsm1 module. (h) Internal hydrophobic network in ScPml39 Rsm1 module helix αAB′. (i) Different view from (h).

The Pml39 zf-C3HC module superimposes with D. melanogaster IAP1-BIR1 (PDB: 3SIP), a representative structure of a canonical BIR domain, with an RMSD of 2.4 Å (Fig. 4a). The Zn ion of the Pml39 zf-C3HC module adopts almost the same position as in canonical BIR domain proteins. Due to the different spacing within the CCHC ZnF motif, helix αC of the ScPml39 zf-C3HC module is tilted by 42° with respect to the corresponding helix αC in D. melanogaster IAP1-BIR1 domain, rendering the distinct spacing a key determinant for the topology of ScPml39 (Fig. 4a). Finally, the conserved aromatic residue succeeding the CCHC ZnF motif—Trp178 in the zf-C3HC module—packs against the C-terminal end of helix αB like a lid and forms numerous hydrophobic contacts in the core of the module (Figs. 2c, 4b).

Structure of the Rsm1 module of ScPml39

The Rsm1 module consists of 122 residues and comprises five α-helices (αA′ (196–211), αAB′ (232–242), αB′ (247–255), αC′ (277–281), and αD′ (297–309)) and one antiparallel β-sheet composed of three β-strands (β1′ (257–259), β2′ (265–268), and β3′ (272–276). The topology of the ScPml39 Rsm1 module deviates even more from canonical BIR domains than the ScPml39 zf-C3HC module (Fig. 2c, Fig. S6). The additional helix αAB′ between the helices αA′ and αB′ extends the sequence of the Rsm1 module and alters its topology (Fig. 4d, Fig. S6).

Sequence analysis alone could not detect the N-terminal BIR consensus sequence motif Rxx(S/T)Ω (Fig. S3), but the structure of the ScPml39 Rsm1 module indeed reveals the presence of this motif in helix αA′, containing Arg202 and Thr205 (Fig. 2). In addition to the conserved hydrogen bond of the Arg202 guanidinium group with the carboxylate group of Glu199, the guanidinium group forms a hydrogen bond with the main-chain oxygen of Leu253 instead of the hydroxyl group of Tyr294 (Fig. 4e). Thus, this residue plays a similar role for the structural integrity of the Rsm1 module as the corresponding arginine in canonical BIR domain proteins.

The extensive insertion between helices αA′ and αB′ is unique to the Rsm1 module among the three BIR-like domain families. While the Ser-rich region immediately preceding helix αAB′ is disordered, the electron density of helix αAB′ is clearly observed, and its C-terminus is connected to helix αB′ through a short segment (Asp243–Asp246) (Figs. 2b, 4g–i). Ile235, Leu238, Phe241, and Phe242 in helix αAB′ tether and stabilize helices αA′, αB′, and αD′ through hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 4h). The insertion of helix αAB′ tilts helix αA′ by 26° with respect to the corresponding helix in canonical BIR domains, such as D. melanogaster IAP1-BIR1 (Fig. 4d). The region between helix αB′ and strand β3′ of the Rsm1 module aligns well with the corresponding region of IAP1-BIR1 and contains the highly conserved GΩ motif (Gly256–Tyr257) between helix αB′ and strand β1′. Leu252 of helix αB′, Tyr257 of strand β1′, Val266 of strand β2′, Ala275 of strand β3′, and L280 of helix αC′ form hydrophobic interactions that stabilize the domain structure (Fig. 4f).

Cys268, Cys271, His288, and Cys292 coordinate Zn and are part of the C-x2-C-x16-H-x3-C ZnF motif (Fig. 2b, Fig. S1). The Zn ion of the Rsm1 module adopts the same position as the Zn ion in canonical BIR domains. Similar to the zf-C3HC module, the distinct CCHC ZnF spacing impacts the structure of the Rsm1 module, with helix αC′ being displaced with respect to canonical BIR domains (Fig. 4d). Thus, the distinct CCHC ZnF spacing between Zn-coordinating residues and helix αAB′ insertion between helices αA′ and αΒ′ represent key determinants of the Rsm1 module. The conserved aromatic residue succeeding the CCHC ZnF motif—Tyr294 in the Rsm1 module—packs against the C-terminal end of helix αB′ like a lid and contributes numerous hydrophobic interactions in the core of the module (Figs. 2c, 4e).

Schizosaccharomyces pombe Rsm1 and human NIPA/ZC3HC1 are structural orthologs of ScPml39

ScPml39 harbors an architecture of two consecutive zf-C3HC and Rsm1 modules. Using structure-guided sequence analysis, we identified S. pombe Rsm1 (UniProtKB: O94506)50,51 and H. sapiens nuclear-interacting partner of ALK (HsNIPA/ZC3HC1, UniProtKB: Q86WB0)38,52,53 as ScPml39 structural orthologs. Both SpRsm1 and HsNIPA/ZC3HC1 feature a domain organization with two tandem zf-C3HC/Rsm1 modules and meet the criteria for conservation of ScPml39 residues essential for structural integrity (Fig. 2b). In SpRsm1, Arg49 and Thr52 would correspond to the ScPml39 residues Arg89 and Ser92 in helix αA, respectively, Gly74-Trp75 of SpRsm1 would correspond to the Gly118-Trp119 motif, Cys85, Cys88, His126, and Cys130 in SpRsm1 would coordinate the zinc ion, and the conserved Trp132 would correspond to Trp178 of ScPml39. Arg156 and Ser159 would be in the helix αA′ of the Rsm1 module. The helix αAB′ seems difficult to predict, but the extended sequence of SpRsm1 in this region is shared with ScPml39. Gly204–Trp205 would locate between helix αB′ and strand β1′. Cys216, Cys219, His241, and Cys245 would coordinate zinc, followed by Trp247. Thus, SpRsm1 harbors all conserved residues related to the structural integrity of ScPml39. zf-C3HC and Rsm1 modules can also be identified in the human NIPA/ZC3HC1 sequence, which can be aligned with that of ScPml39. As for the zf-C3HC module, Arg81 and Thr84 would be in helix αA, Gly106-Trp107 would connect helix αB and strand β1, Cys118, Cys120, His152, and Cys156 would coordinate the zinc ion, and Trp158 would be the final conserved aromatic residue of the consensus sequence in the zf-C3HC module. As for the Rsm1 module, Arg185 and Ser188 would be in helix αA′, Gly255-Trp256 would connect helix αB′ and strand β1′, Cys272, Cys275, His425, and Cys429 would coordinate the zinc ion, and an aromatic residue (Trp431) following Cys429 is also conserved in its putative Rsm1 module. Therefore, the NIPA/ZC3HC1 structure is expected to be highly similar to that of ScPml39 (Fig. 2c), except for an extensive (~ 135-residue) region that is inserted between the Zn-coordinating Cys275 and His425. This analysis suggests that the Pml39 structure is not unique to Saccharomycetaceae, but also found in S. pombe and in humans.

Discussion

The ScPml3977–317 crystal structure revealed two zf-C3HC and Rsm1 modules that tightly interact to form a single domain termed “Pml39 fold”. Our analysis suggests that the Pml39 fold is not an architecture unique to Saccharomycetaceae, but is likely to exist in the 934 proteins whose sequences contain tandem zf-C3HC and Rsm1 modules across all phyla in the Pfam database44.

While all three families of the BIR-like clan (canonical BIR, zf-C3HC, and Rsm1 domains) share conserved key residues responsible for the structural domain integrity, the ZnF motif in the zf-C3HC and Rsm1 families with the consensus sequence C-x2-C-xn-H-x3-C is distinct from the canonical BIR domain (C-x2-C-xn-H-x6-C). Moreover, the additional helix αAB′ insertion is solely found in the Rsm1 module. These findings together with the difficulty to identify homologs on the sequence level suggest that the Pml39 fold has rapidly evolved, as only key residues are conserved. A possible sequence of events for the evolution of the Pml39 fold is as follows: (1) mutation in the CCHC zinc finger motif of an ancestral BIR domain, (2) domain duplication, (3) insertion of helix αAB′ and extra residues between helix αC and the zinc-coordinating histidine in the Rsm1 module. Steps of insertion/deletion are expected to make it more difficult for sequence algorithms to predict the Pml39 fold53. Indeed, the N-terminal consensus motif of canonical BIR domains, Rxx(S/T)Ω, could not be clearly identified in the Rsm1 module in silico (Fig. S3).

The structure of ScPml39 has enabled us to unambiguously identify S. pombe SpRsm1 and human NIPA/ZC3HC1 as structural orthologs of ScPml39 (Fig. 2b). AlphaFold2 also predicts the Pml39 fold for SpRsm1 and human NIPA/ZC3HC1 (Fig. S7)54. Strikingly, the overall amino acid sequence identity/similarity is very low, with only key residues being conserved among ScPml39, SpRsm1, and human NIPA/ZC3HC1 (Fig. 2b). As it is not known whether the function is conserved among these proteins as well, we tested if SpRsm1 could rescue the ScPml39-deficient yeast cell phenotype. Under this heterologous condition, GFP-tagged SpRsm1 did not localize to the nuclear periphery (Fig. S8a). In addition, SpRsm1 expression does not complement the nup133Δ / pml39Δ synthetic interaction in the growth assay (Fig. S8b)27,55. Low sequence identity/similarity in the ScPml39 interacting N-terminal region of Mlp1 (Fig. 1f) may be a barrier to compensate ScPml39 function by SpRsm1 expression in the budding yeast cells, providing a possible reason for the failure of the rescue assay (Fig. S9). Indeed, genetic studies support our hypothesis that SpRsm1 is involved in mRNA export50,51. Moreover, human NIPA/ZC3HC1 has been identified as a nuclear basket-associated protein, required to scaffold Tpr polypeptides56,57. These data, together with the identification of SpRsm1 and human NIPA/ZC3HC1 as structural ScPml39 orthologs, suggest a function of ScPml39 as a scaffold protein to stabilize the nuclear basket. We conclude that ScPml39 is likely conserved in structure and function from yeast to vertebrates.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

DNA fragments encoding full-length (residues 1–334) and truncated (residues 77–317) Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pml39 (UniProtKB: Q03760) and a DNA fragment encoding a C-terminally truncated (residues 1–325) construct of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mlp1 (UniProtKB: Q02455) were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA and cloned into the NcoI/NotI restriction sites of the pET28a vector (Novagen). The constructs were overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)-RIL CodonPlus cells (Agilent Technologies) and grown in LB medium containing appropriate antibiotics. Protein expression was induced at OD600 of ~ 0.6 with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) at 18 °C for 16 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7500×g and 4 °C and lysed with a cell disruptor (Avestin) in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 14.3 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride (AEBSF) (Sigma), 2 µM bovine lung aprotinin (Sigma), and complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). After centrifugation at 35,000×g for 45 min, the cleared lysate was loaded onto a Ni-NTA column (Qiagen) and eluted with an imidazole gradient. Protein-containing fractions were pooled, dialyzed against a buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 250 mM NaCl for full-length ScPml39, 100 mM NaCl for ScPml3977–317, or 150 mM NaCl for ScMlp11–325, and subjected to cleavage with PreScission protease (GE Healthcare) for 5 h at 4 °C. Following hexahistidine-tag removal, ScPml39 proteins were bound to a HiTrap SP column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with a NaCl gradient. For ΔC-ScMlp1, a HiTrap Q column was used. Protein-containing fractions were pooled, concentrated, and purified on a HiLoad Superdex 200 (16/60) gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES–NaOH, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP). Protein concentrations were measured by absorbance at 280 nm, the proteins were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C.

Limited proteolysis

In a volume of 100 µl, full-length ScPml39 at 1.3 mg/ml was incubated with a dilution series of 2 mg/ml porcine elastase at room temperature for 30 min. An aliquot of each dilution was mixed with reducing SDS-PAGE sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The remaining reaction volumes were quenched by guanidinium chloride powder for mass spectrometry analysis. To this end, the samples were run over a reversed phase column (PLRP-S), collected peaks were injected into an ion trap mass spectrometer, and spectra were analyzed by GPMAW58.

Crystallization, data collection, structure determination, and refinement

Crystals of ScPml3977–317 were grown at 20 °C in hanging drops containing 1 μl of the protein at 10 mg/ml and 1 μl of a reservoir solution consisting of 12% (w/v) PEG 8,000 and 0.1 M HEPES–NaOH, pH 7.7. Crystals grew in space group P3121 within a week, were cryo-protected in 25% (v/v) glycerol containing 12% (w/v) PEG 8000, and 0.1 M HEPES–NaOH, pH 7.7, and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the beamlines X29A at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) of the Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) and 8.2.2 at the Advanced Light Source (ALS). Diffraction data were processed in HKL200059. The structure was solved by the single anomalous dispersion (SAD) phasing technique running the script AutoSol of the PHENIX package60. The asymmetric unit contained one molecule. Model building was performed in O61 and Coot62. The final model spanning residues 79–311 was refined in PHENIX to Rfree/Rwork factors of 26.3%/23.3% with excellent stereochemistry and clash score as assessed by MolProbity63. Details for data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. Figures were generated using PyMOL (Schrödinger, LLC), the electrostatic potential was calculated with APBS64. Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank under the accession code 7RDN.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

ITC measurements were performed at 4 °C using a MicroCal auto-iTC200 calorimeter (GE Healthcare). Samples were extensively dialyzed against a buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), and 0.5 mM TCEP. After dialysis, the protein was filtered (0.22 µm) and centrifuged, followed by determining their concentration by UV absorbance at 280 nm. 2 µl of 1.6 mM ScPml3977–317 was injected into 350 µl of 70 µM ScMlp11–325 in the chamber every 180 s. Baseline-corrected data were analyzed using the ORIGIN software to determine the molar ratio (n), dissociation constant (KD), and enthalpy (ΔH). These parameters were subsequently used to determine the free Gibbs energy (ΔG) and the entropic component (TΔS) using ΔG = − RT ln (1/KD) and TΔS = ΔH − ΔG equations, where R and T are the gas constant (1.99 cal/(mol*K)) and absolute temperature, respectively. Thermodynamic parameters are represented as mean values ± standard deviation calculated from three independent measurements.

Size-exclusion chromatography and multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS)

SEC experiments were performed on 100 µl injections of 70 µM ScMlp11–325 with a Superdex 200 (10/300) GL column (GE Healthcare) at 0.5 mL min−1 at 25 °C in 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES–NaOH (pH 7.5), and 0.5 mM TCEP. Absolute molecular weights were determined using MALS. The scattered light intensity of the column eluent was recorded at 18 different angles using a DAWN-HELEOS MALS detector (Wyatt Technology Corp.) operating at 658 nm after calibration with the monomer fraction of Type V BSA (Sigma). Protein concentration of the eluent was determined using an in-line Optilab T-rex interferometric refractometer (Wyatt Technology Corp.). The weight-averaged molecular weight of species within defined chromatographic peaks was calculated using the ASTRA software version 6.0 (Wyatt Technology Corp.), by construction of Debye plots (KC/Rθ versus sin2[θ/2]) at 1-s data intervals. The weight-averaged molecular weight was then calculated at each point of the chromatographic trace from the Debye plot intercept, and an overall average molecular weight was calculated by averaging across the peak.

Yeast strains and plasmids

All S. cerevisiae strains used in this study (Table S1) are haploid, isogenic to BY4742 and were obtained by transformation and/or successive crosses using standard procedures. pRS316-PML391–334-GFP, pRS316-PML3977–317-GFP and pRS316-RSM1-GFP expression vectors were constructed by PCR-based techniques using Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Schizosaccharomyces pombe genomic DNA and pFA6a-GFP(S65T)-KanMX as templates65. Expression of the three transgenes is driven by the PML39 endogenous promoter (300 bp upstream the ATG codon). Unless indicated, cells were grown at 30 °C in rich (YPD, Yeast Extract Peptone Dextrose) or Synthetic Complete (SC) media27,55 and harvested during exponential phase.

In vivo assays

Localization of tagged fluorescent proteins was analyzed in live cells grown in SC medium. Wide-field fluorescence images of GFP-tagged versions of ScPml39 or SpRsm1 were acquired using a Leica DM6000B microscope with a 100 ×/1.4 NA (HCX Plan-Apo) oil immersion objective and a CCD camera (CoolSNAP HQ; Photometrics), and further scaled equivalently using the MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). Whole-cell extracts were prepared from cells grown in SC and analyzed by SDS-PAGE using stain-free precast gels (Biorad) followed by western-blotting with monoclonal anti-GFP antibodies (clones 7.1 and 13.1, Sigma)66. Growth assays were achieved by spotting serial dilutions of cells on SC medium and incubating the plates at 25 °C.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank David King (University of California, Berkeley) for mass spectrometry analysis, Corrie Ralston and Peter Zwart for support during data collection at the Advanced Light Source (ALS), Wuxian Shi for support during data collection at of the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS), Kushol Gupta from the Johnson Foundation Structural Biology and Biophysics Core at the Perelman School of Medicine (Philadelphia, PA) for performing the SEC-MALS analysis, Anna Mienko for assistance with protein expression and purification, the High-Throughput Screening and Spectroscopy Resource Center at Rockefeller University, and the X-Ray Crystallography and Molecular Interactions Facility at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, which is supported in part by National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA56036 and S10 OD017987. X-ray data were collected at beamline 8.2.2 of the ALS, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, supported in part by the ALS-ENABLE program funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, grant P30 GM124169-01, and at beamline X29 of NSLS. This work was supported by funds from the Rockefeller University and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to G.B.), by a grant from the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR-18-CE12-0003, to B.P.), and by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01AI165840, to E.W.D.). We would like to thank the members of the Debler laboratory for helpful discussions.

Author contributions

E.W.D. and B.P. designed the research, interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript. H.H. and E.W.D. performed the x-ray crystal analysis. N.P., D.H.R., and E.W.D. performed protein expression, protein purification, and crystallization. D.H.R. and E.W.D. performed ITC measurements. O.L. and B.P. performed in vivo experiments. E.W.D., B.P., and G.B. provided funding. G.B. provided valuable feedback in the early stages of the project. H.H. drafted the manuscript, which was commented on, edited, and approved by all authors.

Data availability

The datasets and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank under accession code 7RDN.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Günter Blobel is deceased.

Contributor Information

Benoît Palancade, Email: benoit.palancade@ijm.fr.

Erik W. Debler, Email: Erik.Debler@jefferson.edu

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-22183-3.

References

- 1.Wente SR, Rout MP. The nuclear pore complex and nuclear transport. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a000562. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoelz A, Debler EW, Blobel G. The structure of the nuclear pore complex. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011;80:613–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060109-151030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz TU. The structure inventory of the nuclear pore complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2016;428:1986–2000. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin DH, Hoelz A. The structure of the nuclear pore complex (an update) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019;88:725–783. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-011901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blobel G. Gene gating: A hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1985;82:8527–8529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akhtar A, Gasser SM. The nuclear envelope and transcriptional control. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:507–517. doi: 10.1038/nrg2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Köhler A, Hurt E. Gene regulation by nucleoporins and links to cancer. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sood V, Brickner JH. Nuclear pore interactions with the genome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2014;25:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ptak C, Wozniak RW. Nucleoporins and chromatin metabolism. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2016;40:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pascual-Garcia P, Capelson M. The nuclear pore complex and the genome: Organizing and regulatory principles. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2021;67:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonnet A, Palancade B. Regulation of mRNA trafficking by nuclear pore complexes. Genes (Basel) 2014;5:767–791. doi: 10.3390/genes5030767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchwalter A, Kaneshiro JM, Hetzer MW. Coaching from the sidelines: The nuclear periphery in genome regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019;20:39–50. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0063-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmid M, Jensen TH. Transcription-associated quality control of mRNP. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1829:158–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolin SL, Maquat LE. Cellular RNA surveillance in health and disease. Science. 2019;366:822–827. doi: 10.1126/science.aax2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green DM, Johnson CP, Hagan H, Corbett AH. The C-terminal domain of myosin-like protein 1 (Mlp1p) is a docking site for heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins that are required for mRNA export. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:1010–1015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336594100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vinciguerra P, Iglesias N, Camblong J, Zenklusen D, Stutz F. Perinuclear Mlp proteins downregulate gene expression in response to a defect in mRNA export. EMBO J. 2005;24:813–823. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart M. Nuclear export of mRNA. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:609–617. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niepel M, et al. The nuclear basket proteins Mlp1p and Mlp2p are part of a dynamic interactome including Esc1p and the proteasome. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2013;24:3920–3938. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-07-0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saroufim MA, et al. The nuclear basket mediates perinuclear mRNA scanning in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 2015;211:1131–1140. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201503070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hector RE, et al. Dual requirement for yeast hnRNP Nab2p in mRNA poly(A) tail length control and nuclear export. EMBO J. 2002;21:1800–1810. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant RP, et al. Structure of the N-terminal Mlp1-binding domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mRNA-binding protein, Nab2. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;376:1048–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brockmann C, et al. Structural basis for polyadenosine-RNA binding by Nab2 Zn fingers and its function in mRNA nuclear export. Structure. 2012;20:1007–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galy V, et al. Nuclear retention of unspliced mRNAs in yeast is mediated by perinuclear Mlp1. Cell. 2004;116:63–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo CW, et al. Inhibition of splicing and nuclear retention of pre-mRNA by spliceostatin A in fission yeast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;364:573–577. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coyle JH, Bor YC, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold ML. The Tpr protein regulates export of mRNAs with retained introns that traffic through the Nxf1 pathway. RNA. 2011;17:1344–1356. doi: 10.1261/rna.2616111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajanala K, Nandicoori VK. Localization of nucleoporin Tpr to the nuclear pore complex is essential for Tpr mediated regulation of the export of unspliced RNA. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palancade B, Zuccolo M, Loeillet S, Nicolas A, Doye V. Pml39, a novel protein of the nuclear periphery required for nuclear retention of improper messenger ribonucleoparticles. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:5258–5268. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siniossoglou S, et al. A novel complex of nucleoporins, which includes Sec13p and a Sec13p homolog, is essential for normal nuclear pores. Cell. 1996;84:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80981-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debler EW, Hsia K-C, Nagy V, Seo H-S, Hoelz A. Characterization of the membrane-coating Nup84 complex: Paradigm for the nuclear pore complex structure. Nucleus. 2010;1:150–157. doi: 10.4161/nucl.1.2.11120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fasken MB, Corbett AH, Stewart M. Structure-function relationships in the Nab2 polyadenosine-RNA binding Zn finger protein family. Protein Sci. 2019;28:513–523. doi: 10.1002/pro.3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monzon V, Paysan-Lafosse T, Wood V, Bateman A. Reciprocal best structure hits: Using AlphaFold models to discover distant homologues. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.07.04.498216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waterhouse A, et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJE. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi R, et al. A single BIR domain of XIAP sufficient for inhibiting caspases. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:7787–7790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature. 1997;388:300–304. doi: 10.1038/40901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cossu F, Milani M, Mastrangelo E, Lecis D. Targeting the BIR domains of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins in cancer treatment. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2019;17:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verhagen AM, Coulson EJ, Vaux DL. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins and their relatives: IAPs and other BIRPs. Genome Biol. 2001;2:REVIEWS3009. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-7-reviews3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ouyang T, et al. Identification and characterization of a nuclear interacting partner of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (NIPA) J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30028–30036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300883200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bourhis E, Hymowitz SG, Cochran AG. The mitotic regulator Survivin binds as a monomer to its functional interactor Borealin. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:35018–35023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du J, Kelly AE, Funabiki H, Patel DJ. Structural basis for recognition of H3T3ph and Smac/DIABLO N-terminal peptides by human Survivin. Structure. 2012;20:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niedzialkowska E, et al. Molecular basis for phosphospecific recognition of histone H3 tails by Survivin paralogues at inner centromeres. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2012;23:1457–1466. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-11-0904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mace PD, Shirley S, Day CL. Assembling the building blocks: Structure and function of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:46–53. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luque LE, Grape KP, Junker M. A highly conserved arginine is critical for the functional folding of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) BIR domains. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13663–13671. doi: 10.1021/bi0263964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mistry J, et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D412–D419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wheeler TJ, Clements J, Finn RD. Skylign: A tool for creating informative, interactive logos representing sequence alignments and profile hidden Markov models. BMC Bioinform. 2014;15:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laity JH, Lee BM, Wright PE. Zinc finger proteins: New insights into structural and functional diversity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vucic D, Kaiser WJ, Miller LK. A mutational analysis of the baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis Op-IAP. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:33915–33921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.33915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Birnbaum MJ, Clem RJ, Miller LK. An apoptosis-inhibiting gene from a nuclear polyhedrosis virus encoding a polypeptide with Cys/His sequence motifs. J. Virol. 1994;68:2521–2528. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2521-2528.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deveraux QL, Reed JC. IAP family proteins–suppressors of apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:239–252. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoon JH. Schizosaccharomyces pombe rsm1 genetically interacts with spmex67, which is involved in mRNA export. J. Microbiol. 2004;42:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moon DGRM, Park YS, Kim CY, Yoon JH. Isolation of synthetic lethal mutations in the rsm1-null mutant of fission yeast. J. Microbiol. 2010;48:701–705. doi: 10.1007/s12275-010-0353-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bassermann F, et al. NIPA defines an SCF-type mammalian E3 ligase that regulates mitotic entry. Cell. 2005;122:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kokoszynska K, Rychlewski L, Wyrwicz LS. The mitotic entry regulator NIPA is a prototypic BIR domain protein. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2073–2075. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.13.6237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jumper J, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bonnet A, Bretes H, Palancade B. Nuclear pore components affect distinct stages of intron-containing gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:4249–4261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gunkel P, Iino H, Krull S, Cordes VC. ZC3HC1 is a novel inherent component of the nuclear basket, resident in a state of reciprocal dependence with TPR. Cells. 2021;10:1937. doi: 10.3390/cells10081937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gunkel P, Cordes VC. ZC3HC1 is a structural element of the nuclear basket effecting interlinkage of TPR polypeptides. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2022;33:ar82. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E22-02-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peri S, Steen H, Pandey A. GPMAW—A software tool for analyzing proteins and peptides. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:687–689. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01954-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Macromolecular crystallography part A. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liebschner D, et al. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: Recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Struct. Biol. 2019;75:861–877. doi: 10.1107/S2059798319011471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jones TA, Zou J-Y, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Williams CJ, et al. MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 2018;27:293–315. doi: 10.1002/pro.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Longtine MS, et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lautier O, et al. Co-translational assembly and localized translation of nucleoporins in nuclear pore complex biogenesis. Mol. Cell. 2021;81:2417–2427.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank under accession code 7RDN.