Abstract

We report a herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant which failed to amplify with a commonly used glycoprotein D primer set. The virus contained a nine-base deletion in the gene's 5′ nontranslated region. The altered amplicon was clearly distinguishable on a 4% high-resolution agarose gel.

Herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) infections are among the most commonly clinically encountered infections in medical practice and, worldwide, are major causes of mucocutaneous ulceration (2, 6, 8, 11); in Northern Ireland, HSV-1 is the most commonly recognized cause of genital ulceration in women (4). The virus attaches to cells and gains entry through the action of a number of surface glycoproteins. Aurelius et al. (1) described a nested primer set targeting the nucleic acid sequence of HSV-1 glycoprotein D (gpD), which has been widely used and cited in over 220 publications. We have used this set in a multiplex nested PCR for HSV-1 and HSV-2 (5) and have identified an HSV-1 mutant which yielded the expected first-round product but repeatedly failed second-round amplification; the outer and inner primer pairs were labeled 5A-5B and 5C-5D, respectively. The mutant virus was demonstrated in a specimen (16253/99) of dermal scrapings, submitted on a glass slide, from an 84-year-old woman who presented with a discrete vesicular rash on the left cheek which healed without specific antiviral therapy. The presentation of the vesicular lesions was preceded by a prodromal sensation and was clinically diagnosed as an HSV eruption. The diagnosis was made at a dermatology clinic which the patient attended routinely for the skin condition bullous pemphigoid, which was controlled by the application of dermovate ointment as required.

To investigate the failure of second-round amplification, we sequenced through the internal primer sites of the mutant's first-round product, plus those of a second HSV-1 isolate (20209/99) and the HSV-1 laboratory control.

The first- and second-round PCRs were undertaken as previously described (5). Briefly, the master mixes were made in nuclease-free water (NFW) with Promega Taq DNA polymerase (in storage buffer B), magnesium-free reaction buffer (10×) supplied with the Taq enzyme, MgCl2 (Promega), and primers. The amounts of final working concentrations of the components of each 25-μl test mixture were 5 pmol for each primer, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 3.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.2 mM for each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.625 U of Taq enzyme. Hot-start PCR was carried out in a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp 2400 thermal cycler with the cycling conditions shown in Table 1. First- and second-round products were visualized together on an ethidium bromide-stained 4% MetaPhor high-resolution agarose gel (FMC BioProducts, Vallensbaek Strand, Denmark). The primers used are numbered with reference to the HSV-1 gpD published sequence (12) and consisted of the outer primers 5A (ATCACGGTAGCCCGGCCGTGTGACA [gpD nucleotides 23 to 47]) and 5B (CATACCGGAACGCACCACACAA [gpD nucleotides 222 to 243]) and the inner primers 5C (CCATACCGACCACACCGACGA [gpD nucleotides 55 to 75]) and 5D (GGTAGTTGGTCGTTCGCGCTGAA [gpD nucleotides 170 to 192]).

TABLE 1.

PCR cycling conditionsa

| Parameter | First round | Second round |

|---|---|---|

| Denaturation | 94°C, 10 s | 94°C, 10 s |

| Annealing | 58°C, 10 s | 67°C, 10 s |

| Extension | 72°C, 30 s | 72°C, 30 s |

| No. of cycles | 35 | 25 |

The specimens were held on ice and transferred to the thermal cycler and held at 94°C, ensuring a hot-start procedure.

First-round DNA products were purified with a GFX gel band purification kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Uppsala, Sweden). The DNA solution was added to 500 μl of capture buffer and transferred to the GFX column. It was mixed and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 s, washed with 500 μl of wash buffer, and recentrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 s. The DNA was eluted off the column with 250 μl of NFW. Cycle sequencing of the first-round products was undertaken with the Thermo Sequenase fluorescent-labeled primer cycle sequencing kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc.). Forward sequencing was initiated with the outer positive strand, primer HSV-1 5A, and reverse sequencing was undertaken with the outer negative strand, primer HSV-1 5B. The primers were labeled at the 5′ nucleotide base with the fluorescent dye Cy5 and were used at a final concentration of 2 pmol/μl in a total volume of 20 μl for each dideoxynucleotide mix. Cycle sequencing was carried out in a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp 9700 thermal cycler, with the following cycling conditions: denaturation at 95°C for 30 s and annealing-extension at 65°C for 30 s for 20 cycles. When cycling was complete, 3 μl of formamide loading dye was added to each dideoxynucleotide mix and loaded immediately (without denaturation) onto a ReproGel High Resolution sequencing gel (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc.). The gel was run on an ALFexpressII under the following conditions: 1,500 V, 60 mA, 30 W, 55°C.

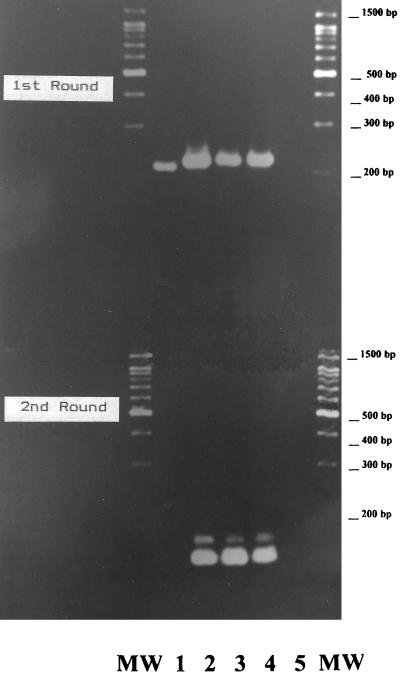

Sequences were generated in both directions through the site of primer HSV-1 5D but only in the reverse direction through site 5C; a readable sequence in the forward direction only began after the primer site position. Site 5D was unchanged from the original description in all three viruses, but site 5C contained a nine-base deletion in specimen 16253/99, spanning gpD positions 66 to 74 inclusive, as shown in Table 2. This deletion lies in the nontranslated region of the gene 167 bases before the initiating methionine. The 5C site in the other two viruses was unchanged from the original description. In addition, all three viruses contained an additional thymidine residue at position 77 with respect to the gpD sequence of the reference strain. The MetaPhor gel of the PCR products is shown in Fig. 1 and clearly demonstrates the failure of second-round amplification. It also shows that the first-round product of 16253/99 is smaller than those of the other HSV-1 viruses in the test.

TABLE 2.

HSV-1 control and isolate sequences through HSV gpD positions 49 to 102

| Designation | 5′ to 3′ sequence spanning HSV-1 positive strand gpD (bases 49 to 102)a |

|---|---|

| Primer 5C | ......CCATACCGACCACACCGACGA...... |

| HSV-1 (+) Control | TATCGTCCATACCGACCACACCGACGAATCCCCTAAGGGGGAGGGGCCATTTTA |

| 16253/99 Mutant | TATCGTCCATACCGACC.........AATCCCCTAAGGGGGAGGGGCCATTTTA |

| 20209/99 Isolate | TATCGTCCATACCGACCACACCGACGAATCCCCTAAGGGGGAGGGGCCATTTTA |

The adenine base of the initiating methionine lies at position 241. All three viruses contained an additional thymidine residue at position 77 (underlined) with respect to the gpD sequence of the reference strain.

FIG. 1.

Nested PCR demonstrating the altered size of the HSV-1 mutant first-round product and its complete failure in second-round amplification. PCR products and water control are shown on a 4% MetaPhor high-resolution resolving gel. Lane 1, the deletion mutant 16253/99; lanes 2 and 3, two HSV-1 isolates; lane 4, the HSV-1 positive control; lane 5, the water control; lanes MW, molecular weight markers. The expected first- and second-round products are 221 and 138 bp, respectively.

The MetaPhor gel is designed for the high-resolution separation of 20- to 800-bp DNA fragments and can resolve PCR fragments that differ in size by 2%. In routine practice, we use a 2% agarose gel which would be inadequate for this purpose, and it was not until we had the sequence results that we suspected that the size of the first-round product was altered.

The deletion mutation explained the observed second-round amplification failure. However, the deletion mutation appears uncommon. This has been our only example of a second-round amplification failure in over 200 HSV-1 gpD sequences amplified from clinical specimens. We were also unable to identify additional database-lodged sequences sharing the deletion. The virus was recovered from an 84-year-old woman who presented with a vesicular eruption on her left cheek. In our laboratory, less than 5% of the HSV-1 viruses recovered by PCR or isolated in culture come from patients over 60 years of age, a figure that falls to less than 3% for those over 80 years. The proportions of requests for HSV detection from those over 60 and 80 years of age are 9.3 and 4.1%, respectively, calculated from 4,144 consecutive specimens received. It is possible that this virus is representative of those in circulation over 8 decades ago or it may have undergone the mutation while harbored in the patient's sensory ganglia. The ease with which the MetaPhor gel detected the deletion could show that this is a simple approach for those interested in searching for insertion or deletion mutants of this or other viruses.

gpD acts to stabilize attachment of the virus, postadsorption, to the target cell membrane, plays an integral part in viral entry to the cell (10), and can be used to generate a protective immune response (7). Altered processing of gpD can affect HSV-1 neurovirulence (3), an alteration that can result from a single amino acid change (9). Although there is nothing to indicate an altered neurovirulence in this case, this nonlethal mutation left the virus still capable of both replication and producing dermal lesions.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. A. Bingham, consultant dermatologist, Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast, United Kingdom, for providing the clinical details of this patient and M. Clulow for developing and printing the photograph in Fig. 1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aurelius E, Johansson B, Skoldenberg B, Forsgren M. Encephalitis in immunocompetent patients due to herpes simplex virus type 1 or 2 as determined by type-specific polymerase chain reaction and antibody assays of cerebrospinal fluid. J Med Virol. 1993;39:179–186. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890390302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyrer C, Jitwatcharanan K, Natpratan C, Kaewvichit R, Nelson K E, Chen C Y, Weiss J B, Morse S A. Molecular methods for the diagnosis of genital ulcer diseases in a sexually transmitted disease clinic population in northern Thailand: predominance of herpes simplex virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:243–246. doi: 10.1086/515603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bower J R, Mao H, Durishin C, Rozenbom E, Detwiler M, Rempinski D, Karban T I, Rosenthal K S. Intrastrain variants of herpes simplex virus type 1 isolated from a neonate with fatal disseminated infection differ in the ICP34.5 gene, glycoprotein processing, and neuroinvasiveness. J Virol. 1999;73:3843–3853. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3843-3853.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christie S N, McCaughey C, Wyatt D E, O'Neill H J, Coyle P V. Herpes simplex type 1 and genital herpes in Northern Ireland. Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8:68–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coyle P V, Desai A, Wyatt D, McCaughey C, O'Neill H J. A comparison of virus isolation, indirect immunofluorescence and nested multiplex polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of primary and recurrent herpes simplex type 1 and type 2 infections. J Virol Methods. 1999;83:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(99)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.do Nascimento M C, Sumita L M, de Souza V A, Pannuti C S. Detection and direct typing of herpes simplex virus in perianal ulcers of patients with AIDS by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:848–849. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.848-849.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heiligenhaus A, Wells P A, Foster C S. Immunisation against HSV-1 keratitis with a synthetic gD peptide. Eye. 1995;9:89–95. doi: 10.1038/eye.1995.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mertz K J, Trees D, Levine W C, Lewis J S, Litchfield B, Pettus K S, Morse S A, St. Louis M E, Weiss J B, Schwebke J, Dickes J, Kee R, Reynolds J, Hutcheson D, Green D, Dyer I, Richwald G A, Novotny J, Weisfuse I, Goldberg M, O'Donnell J A, Knaup R. Etiology of genital ulcers and prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus coinfection in 10 US cities. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1795–1798. doi: 10.1086/314502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell B M, Stevens J G. Neuroinvasive properties of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein variants are controlled by the immune response. J Immunol. 1996;156:246–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajcani J, Vojvodova A. The role of herpes simplex virus glycoproteins in the virus replication cycle. Acta Virol. 1998;42:103–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Risbud A, Chan-Tack K, Gadkari D, Gangakhedkar R R, Shepherd M E, Bollinger R, Mehendale S, Gaydos C, Divekar A, Rompalo A, Quinn T C. The etiology of genital ulcer disease by multiplex polymerase chain reaction and relationship to HIV infection among patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in Pune, India. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:55–62. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199901000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson R J, Weis J H, Salstrom J S, Enquist L W. Herpes simplex virus type-1 glycoprotein D gene: nucleotide sequence and expression in Escherichia coli. Science. 1982;218:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.6289440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]